Abstract

Sample digital technology is a powerful method for absolute quantification of target molecules such as nucleic acids and proteins. The excellent sample stability and mass production capability has enabled the development of microwell array-based sample digitizing methods. However, in current microwell array chips, samples are loaded by the liquid scraping method, which requires complex manual operation and results in a low filling rate and limited hole filling uniformity. Here, we perform sample loading of a through-hole array chip by a microfluidics-driven method and design a double independent S-shaped flow channels sandwiched through-hole array chip. Because of the capillary force and capillary burst pressure, the sample flowing in the channel can be trapped into through-holes, but cannot flow through the other side. Via air flow and displacement of the remaining sample in the channel, the sample can be partitioned consistently, with zero surplus sample residue in the channel. We evaluated the actual performance of the sample-loading process: the chip enables 99.10% filling rate of 18 500 through-holes, with a grayscale coefficient of variation value of 6.03% determined from fluorescence images. In performing digital polymerase chain reaction on chip, the chip demonstrates good performance for the absolute quantification of target DNA. The simple and robust design of our chip, with excellent filling rate and microsample uniformity, indicates potential for use in a variety of sample digitization applications.

I. INTRODUCTION

In recent years, with the development of microfabrication technology and the increase in demand for high-throughput sample analysis, high-throughput biological sample analysis methods such as digital PCR1 and digital enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)2,3 have emerged. Compared with real-time PCR, digital PCR, which is one of the most widely developed examples of such technologies, does not rely on standard curves or reference genes4,5 and has higher accuracy6,7 and sensitivity.8,9 Therefore, digital PCR has a great value in both research and clinical applications such as liquid biopsy10,11 and prenatal diagnosis.12,13

Sample partitioning is a critical step in digital PCR. According to the type of the reaction unit, current digital PCR chips can be divided into three categories: microchamber,14 microdroplet,15 and microwell.16

The microchamber digital PCR chip consists of numerous microchambers and integrated flow channels. In recent years, many microchamber-based digital PCR chips have been reported. Hansen et al.17 achieved a sample throughput of 1 × 106, and Mu et al.18–20 proposed a self-priming chip. Although the microchamber-based digital PCR chip has developed rapidly and been used in many applications, it suffers from fabricating defects due to its complex structure, small feature size, and multiple-step fabricating process, which is difficult to produce on a large scale. The microdroplet digital PCR chip divides the sample into several independent water-in-oil droplets through microfluidic technology21–24 to realize digital single-molecule detection. The droplet chip is capable of continuously generating droplets without wasting sample volume. Additionally, in order to ensure the stability of droplet generation, stable pressure conditions are necessary.25 Furthermore, the droplets are prone to fragmentation and fusion. The basic feature of a microwell digital PCR chip is the presence of etched wells or through-holes on the surface of a plate, such as a glass or silicon wafer, which serve as reaction units. The sample is filled into the units. The structure and fabrication of microwell chips are relatively simple, and the chips can be mass-produced. Because of its unique physical partition, the sample in the unit is relatively stable.26 At present, most microwell chips are sampled by the scraping method,27–29 whose operation is complex. When scraping samples on the microwell, any disturbance will cause unstable contact between the sample and the microwell, which affects the filling rate and uniformity. These problems directly affect the dynamic range and accuracy of the results; in addition, the sample may be easily exposed to the air during the scraping process, which may increase the risk of sample contamination.

The microwell chip described in this paper possesses the advantage of facile sample loading of the through-hole array chip and ease of operation of the microchannel. The double flow channel sandwiched chip (DFCS-chip) contains a through-hole array chip and two independent flow channels to achieve sample digitization based on capillary force, capillary burst pressure,30,31 and flow shear force. Detailed simulation analysis of the sample loading process is performed based on the dynamic contact angle theory; a DFCS-chip with excellent performance is prepared and digital PCR amplification is carried out. The concept and workflow of the DFCS-chip for digital PCR is shown in Fig. 1. Compared with the traditional microwell array chip and its sample scraping method, the DFCS-chip is able to achieve rapid and robust sample digitization with a high filling rate (99.10%, which is greatly better than that of general microwell array chip32) and excellent microsample uniformity (6.03% of grayscale CV value from actual fluorescence image). In addition, the flow channel strategy reduces sample exposure to external contaminants. In general, this chip provides a simple-to-use and low-cost method to quantify nucleic acids.

FIG. 1.

Concept and workflow of the DFCS-chip for digital PCR. (a) The sample is injected into the upper channel and trapped into through-holes because of capillary force; the sample cannot flow through microwells owing to capillary burst pressure. (b) The sample on the surface of the microwell array chip is totally displaced by air flow, and many microsamples are generated. (c) Oil fills the channels under gravity and isolates the microsamples. (d) and (e) After thermal cycling, the results are read by fluorescence imaging.

II. MATERIALS AND METHODS

A. Chip design and fabrication

The DFCS-chip consists of an S-shaped cover layer and a bottom layer with a silicon-based through-hole array chip. The through-hole array chip is sandwiched between two S-shaped flow channels. The structure of the DFCS-chip is shown in Fig. 2. The overall size of the through-hole array chip is 10 × 10 × 0.3 mm3. The chip contains regularly arranged regular hexagonal-shaped through-holes. The diagonal length of the through-hole is 60 μm and the span size of the through-hole array is 16 μm. The design principle of through-hole array is described in the supplementary material. Due to the digital PCR thermal cycling, the generation of bubbles is difficult to avoid completely. Therefore, it is necessary to provide a motion path for the bubbles leaving from through-hole array area. Symmetrical double S-shaped flow channels enable the two outlets share the same corner of the through-hole array chip and can also reduce the flow resistance of bubbles. By increasing the width of the flow channel of the outlet, the bubbles in the upper and lower channels can rise along the S-shaped channel when the side of the outlet is raised. The isosceles trapezoidal oil reservoir at the outlet of the S-shaped channel is used to store the generated bubbles and then fill the through-hole array chip area with oil. Due to the increase of the span size of oil reservoir, once the bubbles enter the oil reservoir and fused, it is hard to overcome the surface tension to enter the through-hole array area again. The design of oil reservoir helps the long-term storage of the chip. The overall flow channel is composed of two “PDMS-glass” layers. Glass is used as the anti-evaporation layer. Unlike the conventional PDMS-glass bonding method, we directly put the glass slide into the uncured PDMS, so that the glass and the flow channel are in close contact. This method can minimize the loss of the sample and generation of bubbles. The depth of the main channel is 200 μm, with an inlet flow channel width of 1 mm and an outlet flow channel width of 1.5 mm. The main hexagonal channel width is 9 mm, with an oil chamber width of 5 mm. All the simulations are conducted with the FLUENT FEM software (COMSOL Multiphysics 5.4, COMSOL Inc.).

FIG. 2.

Schematic diagram of the DFCS-chip structure. (a) Schematic diagram of the DFCS-chip structure, with insets showing the array and through-hole geometries. (b) Schematic of layered chip structure; the through-hole array chip is embedded into the groove of PDMS. Glass is used as anti-evaporation layer.

1. Fabrication of through-hole array chip

Based on previous research by our group, a silicon wafer was processed by chromium plating, lithography, inductively coupled plasma etching, chromium removal, mechanical thinning, thermal oxidation, and dicing processes, in that order.33 The detailed fabrication process is shown in Fig. 3(a).

FIG. 3.

Fabrication process of through-hole array chip and “PDMS-glass” layers. (a) Fabrication process of through-hole array chip. (b) Fabrication process of “PDMS-glass” layers.

2. “PDMS-glass” layer preparation and oxygen plasma bonding

Aluminum molds were fabricated by a 3-axis computer numerical controlled (CNC) milling machine (VA4, TSUGAMI). The molds were sequentially rinsed in acetone, ethanol, and ultrapure water using an ultrasonic cleaner for 10 min, and then dried with nitrogen. The molds were placed into an ammonia: hydrogen peroxide solution with a volume ratio of 7:3 for 12 h, and the surface of the molds was hydrophilized. The molds were then cleaned and immersed into 1% heptadecafluoro-1,1,2,2-tetradecyl silane: n-hexane solution for 30 min, followed by placing on a 90 °C hot plate to bake for 30 min in order to ensure that the mold is hydrophobic, and to facilitate polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) (Sylgard 184, DOWSIL) release from the molds.

Then, 5 g of degassed 10:1 (monomer: curing agent) PDMS was poured onto the molds. A coverslip was placed under the PDMS on the cover layer mold, and a glass slide was put on the PDMS on the bottom layer mold. After baking the molds (100 °C for 1 h), PDMS was gently peeled off and holes were punched at the inlet and outlet positions. The fabrication process of the “PDMS-glass” layer is shown in Fig. 3(b). The two layers were bonded with oxygen plasma (YZD08-5CS, SAOT Tech Co., Ltd.) at 0.01 atm, 0.1 ml/min oxygen flow rate and 120 W RF power for 2 min.

B. Chip operation

First, a chip holder was connected to PTFE tubes, and the DFCS-chip was fixed in the holder. Secondly, a 25 μl sample was tipped into the upper channel's inlet and then pumped by a syringe pump (LSP01-1A, Baoding Lange Constant Flow Pump Co., Ltd.), with an air flow rate of 1 μl/s, until the surplus sample was pumped out from the upper channel outlet. Finally, 75 μl fluorinated oil (FC-40, 3M Fluorinert™) was tipped into the inlet of the two channels. Fluorinated oil is able to fill the channels owing to its low surface tension (16 mN/m) and low dynamic viscosity (2.5 mPa s). The entire operation process was completed in 2–3 min.

C. Digital PCR experiment

In this work, the wild type JAK2 plasmid DNA, whose corresponding probe was labeled with FAMTM dye, was used as the template. The template was purchased from Sangon Biotech. To assess the performance of the DFCS-chip, the template was diluted from 1000 copies/μl to 10 copies/μl. All DNA samples were stored at −20 °C prior to use. The reaction mix in a total volume of 25 μl consisted of 12.5 μl QuantStudio™ 3D Digital PCR Master Mix, 1.25 μl TaqMan™ Liquid Biopsy dPCR Assay, and 8.75 μl nuclease-free water (all purchased from Thermo Fisher), and diluted template 2.5 μl. Each reaction mix was premixed off-chip before sampling.

After sampling, the chip was placed on a flat PCR apparatus placed at a tilt angle of 30°, to perform a “two-step” PCR thermal cycling. The side of the chip with the oil reservoir was placed upward. The thermal cycling including: a hot start stage at 95 °C for 10 min to activate Taq DNA polymerase. Then, 40 cycles of 94 °C for 30 s and 60 °C for 1 min were performed to amplify the target DNA. The entire PCR reaction took about 2.2 h.

D. Image acquisition and analysis

All bright-field images were acquired with an optical microscope (Union DH2, Shanghai Tuojing Industrial Measurement Instrument Co., Ltd.). The fluorescence images were obtained with an inverted fluorescence microscope (Axio Observer A1, Zeiss) and a complementary metal-oxide-semiconductor (CMOS) fluorescence imaging platform built by our group. The platform contains three fluorescence channels for FAM, VIC, and ROX. All the fluorescence images were captured under the FAM channel. The center wavelength of excitation light is 488 nm, and the center wavelength of emission light is 532 nm. The images were analyzed by MATLAB to calculate the mean grayscale value of each microsample and quantify the number of positive microsamples in each DFCS-chip. Finally, the copy number of the template in each chip was calculated according to the Poisson statistics principle.

III. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

A. Simulations of sample loading

1. Capillary hole filling speed and sample stability in through-holes

The schematic of the sample capillary filling process and the sample capillary burst out process is shown in Figs. 4(a) and 4(b). Gas–liquid interface pressure difference can be calculated by the Young–Laplace equation. We estimate the interfacial pressure difference of the sample in the regular hexagonal through-hole by equating the gas–liquid interface to a spherical surface and using the equivalent hydraulic diameter.

FIG. 4.

Schematic and simulation of capillary process and capillary burst out process (fluid blue: water phase, fluid red: air). (a) Schematic of capillary process. (b) Schematic of capillary burst out process. (c) Gas–liquid interface of the through-hole capillary filling process under the CA of 45°. (d) Capillary filling time of digital PCR sample at different CAs. (e) The pressure change of the interface during the extrusion of digital PCR sample from the through-holes under different CAs; the peak of the curve represents the capillary burst pressure.

For the capillary filling process,

| (1) |

For the capillary burst out process,

| (2) |

where

| (3) |

Here, ΔP is the pressure difference between the inside and outside of the liquid interface, σ is the surface tension of the liquid, θ is the contact angle (CA) between the water phase and the wall, D is the equivalent hydraulic diameter of the through-hole, A is the cross-sectional area of the through-hole, and L is the circumference of the through-hole. The cosθ1/D and cosθ2/D represent the curvature of the spherical gas–liquid interface in the capillary filling process and capillary burst out process, respectively.

We simulated the digital PCR sample capillary process by “two phase flow, level set” module with a dynamic viscosity of 2 mPa s, a density of 1000 kg/m3, and a surface tension of 35.0 mN/m (measured by the capillary rise method). Figure 4(c) describes the shape of liquid interface of the capillary filling process, and Fig. 4(d) describes the rise of capillary interface under different CAs. As the CA increases, the curvature of the gas–liquid interface decreases, which means the capillary force ΔP1 decreases. Therefore, sample needs more time to fill through-holes. According to the simulation results, the sample can theoretically fill a 0.3-mm-high through-hole in 1–5 ms, with CA ranging from 15° to 75°. The silicon-based through-hole array chip we used was thermally oxidized with CA of 45°. When the sample flows into the channel, the through-hole should be filled in 1.5 ms.

After the through-holes are filled, the air pumped into the upper channel pushes the surplus sample out of the chip through the outlet of upper channel. If the feed pressure exceeds ΔP2, the sample in the through-holes will be pushed out of the through-holes where it then adheres to the surface of the through-hole array chip, causing the microsamples to come into contact with each other. We applied a velocity boundary condition of 0.2 m/s to the water phase in the through hole to observe the pressure difference of the water phase extruding from the through hole. The peak of the curve in Fig. 4(e) describes the ΔP2 under different CAs. As the CA increases, the curvature of the gas–liquid interface increases and then capillary burst pressure increases. The results show that the sample in the through-hole is stable under a pressure of 1000 Pa or higher theoretically.

2. Feasibility analysis of the S-shaped flow channel

Prediction of the “liquid–gas” interface during the chip loading process is critical. The sample inflow process requires the sample to be fully expanded evenly on the surface of the through-hole array chip area to achieve a high filling rate of the chip. The surplus liquid removal process requires the sample to be as little sample residual as possible on the surface of the through-hole array chip area to achieve sufficient sample partition and improve digitization efficiency, and also to avoid interference of residual sample with other microsamples during the reaction, observation, and analysis process.

The flow channel structure needs to be determined according to the dynamic CA in flow channel. The value of dynamic CA in flow channel is affected by many factors such as liquid surface properties, pressure, velocity, and channel structure. In our flow channel, the pressure and flow rate conditions of the water phase change insignificantly, and the geometric structure of each contact line position is the same. Therefore, the dynamic CAs in the flow channel is mainly affected by the property of the water phase. In the flat flow channel with a low depth to width ratio, the dynamic CA between the water phase and the sidewall of the flow channel mainly determines the shape of the interface under Stokes flow.

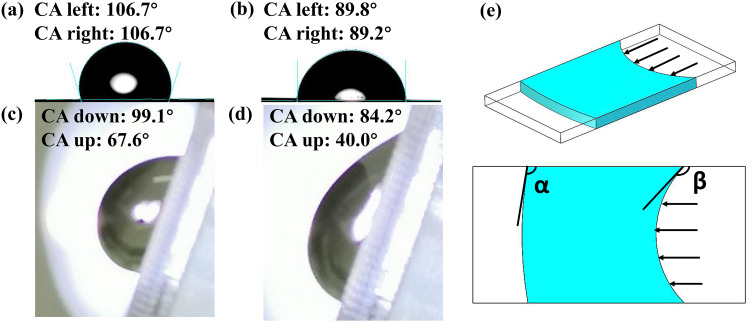

The static CA and dynamic CA on the flat PDMS surface of pure water and the digital PCR sample used in this paper are shown in Figs. 5(a)–5(d). CA down means advancing CA, and CA up means receding CA. the measurements show a significant difference. To accurately describe the dynamic CA of water phase in the flow channel, we define α as the dynamic CA of water phase inflow and β as the dynamic CA of water phase outflow depicted in Fig. 5(e). If the inflow CA is larger than the angle of the corner of the flow channel, the “liquid–gas” interface tends to cross the air at the corner and directly contact the opposite channel side and the through-holes at the corner would not be filled. Similarly, the water phase would be left at the corner if the outflow CA is too large. For digital PCR sample loading process, the flow channel should be able to achieve sufficient inflow of sample with the inflow CA of about 84° and also to contain no sample residue at under approximately 140° of the outflow CA theoretically. Taking into account the viscous or capillary forces of the upper and lower surfaces of the flow channel on the water phase, the actual inflow and outflow contact angle will change around the theoretical value.

FIG. 5.

Measured values of static CA and dynamic CA, and schematic diagrams of inflow CA and outflow CA. (a) Static CA of water on PDMS surface. (b) static CA of digital PCR sample on PDMS surface. (c) Dynamic CA of water on PDMS surface with 70° tilt angle. (d) Dynamic CA of the digital PCR sample on PDMS surface with 70° tilt angle. (e) Schematic of inflow CA α (advancing CA of the water phase) and outflow CA β (supplementary angle of the receding CA of the water phase).

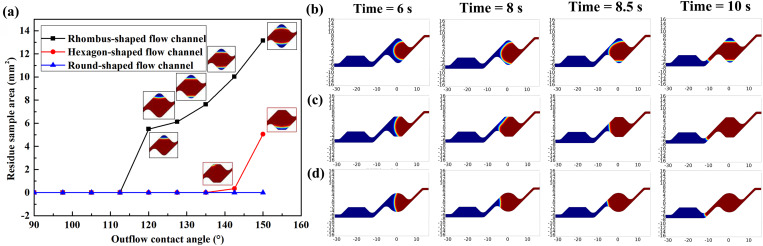

According to the structure of 10 × 10 mm through-hole array chip, we proposed three kinds of flow channels: rhombus-shaped flow channel with 9 mm of side length, hexagon-shaped flow channel with 9 mm of span size, and round-shaped flow channel with 9 mm of diameter. All three kinds of flow channels meet the condition of sufficient sample inflow. Figure S3 in the supplementary material shows the simulation results of sample inflow process. We compared and simulated the residue sample area under outflow CAs ranging from 90° to 150° of these three flow channels. The model uses the “two phase flow, level set” module with an inlet flow rate of 0.01 m/s. The blue fluid parameters are set to those of the digital PCR sample, and the red fluid parameters are set to those of air. Results are shown in Fig. 6(a). The rhombus-shaped flow channel enables zero sample residue with an outflow CA of less than 112.5°, the hexagon-shaped flow channel greatly expands the allowable range of outflow CA, to 137.5°. Under the outflow CA of 142.5°, a droplet-like sample residue occurs at the corner of the hexagon-shaped flow channel with a span size of 9 mm. The round-shaped channel shows superior stability with zero surplus sample residue. The shape of interface of these three flow channels under outflow CA of 135° is shown in Figs. 6(b)–6(d). Among the three kinds of flow channels we proposed, the hexagon- and the round-shaped flow channel can theoretically achieve stable digital PCR sample loading. For digital PCR experiment, limit of detection is an important issue which is related to the number of through-holes filled with the sample. Therefore, it is necessary to choose a flow channel structure that can not only ensure the stability of sample loading, but also increase the number of through-holes included in the flow channel. Under the case of a 10 × 10 mm through-hole array chip, the above-mentioned hexagon-shaped flow channels and round-shaped flow channels can cover 74.00% (18 500 through-holes) and 71.75% (17 938 through-holes) respectively. Therefore, which flow channel to choose needs to be verified by experiment.

FIG. 6.

Simulations of the sample-air displacement process (blue fluid: sample, red fluid: air). (a) Volume variation of the simulated residual sample in the through-hole array area at different outflow CAs. (b)–(d) Simulations of the interface of the rhombus-shaped flow channel, hexagon-shaped flow channel, and round-shaped flow channel at an outflow CA of 135°.

The flow velocity of the sample in the channel directly determines the loading speed of the chip and the stability of the sample in through-hole. The simulation of velocity and pressure distribution of the hexagon- and round-shaped flow channel above the through-hole array section is shown in Figs. 7(a) and 7(c). The height of flow channel is 0.2 mm, and the sample velocity of the inlet range from 2.5 μl/s to 75 μl/s. The pressure distributions at each point on the midline of the hexagon and round-shaped flow channel are shown in Figs. 7(b) and 7(d). When the inlet flow rate reaches 75 μl/s, the maximum pressure value is about 800 Pa and the pressure value at the central area of the chip is about 400 Pa. Under conditions where the CA of the through-hole ranges from 15° to 75°, microsamples can withstand the above pressure and remain stable.

FIG. 7.

Simulation of the pressure field of the sample in flow channel. (a) Velocity field and pressure field distribution of the hexagon-shaped flow channel. (b) Pressure distribution on the midline of the hexagon-shaped flow channel at different flow rates. (c) Velocity field and pressure field distribution of the round-shaped flow channel. (d) Pressure distribution on the midline of the round-shaped flow channel at different flow rates.

B. Chip loading stability and uniformity

In order to test the performance of the flow channel and verify the rationality of the above theory, we conducted sample loading experiments both on a hexagon-shaped flow channel with a span size of 9 mm and a round-shaped flow channel with a diameter of 9 mm, respectively. In order to avoid the interference of inertial force, water and digital PCR sample are both loaded on to the chips with a driven flow rate of 1 μl/s. The water phase inflow and outflow processes are shown in Fig. 8. The actual inflow CAs and outflow CAs in each image were measured by SolidWorks software, compared with the measured results in Fig. 5. For water and digital PCR sample, the mean value of the inflow CA in both channels is greater than the respective advancing CA of 99.1° and 84.2°; the mean value of the supplementary angle of the outflow CA in both channels is a little less than the respective receding CA of 67.6° and 40°. No obvious water phase residue in the channels. Since the hexagon-shaped flow channel has more through holes, the DFCS-chip of the hexagon-shaped flow channel is more suitable for digital PCR.

FIG. 8.

Liquid interface of sample loading process. The border of the flow channel is outlined with black lines. The values in parentheses are the inflow or outflow CAs on the corresponding side of the flow channel, the CAs are marked with auxiliary lines in the first image of each row of images. (a) Interface of pure water in the hexagon-shaped flow channel. (b) Interface of pure water in the round-shaped flow channel. (c) Interface of digital PCR sample in the hexagon-shaped flow channel. (d) Interface of digital PCR sample in the round-shaped flow channel.

For the results that the inflow CAs are greater than the theoretical values, we believe that these are the following reasons. The first reason is the difference in flow resistance between the center and sides of the flow channel. Due to the friction of the walls, the water phase on the sidewall is more difficult to flow than the water phase in the central area. When the water phase cannot spontaneously wet the wall and then move forward, the inflow contact angle will be greater than the theoretical value under pressure driven. Besides, the structure of the through-hole array brings great resistance to the flow of the water phase. The moment that water phase flows to the edge of through-hole, the water phase has to overcome the surface tension and then wets the hole wall, which process creates a pressure opposite to the direction of water phase flow. Therefore, the flow obstruction on the sidewall is more significant. In the outflow process, the resistance of the sidewall still exists. In addition, the water phase in the flow channel needs to be separated from the water phase in the through hole, which will create additional flow resistance. The above reasons cause the outflow contact angle to be higher than the theoretical value. However, the deviations of the inflow contact angle and the outflow contact angle still need further study.

The DFCS-chip based on hexagon-shaped flow channel can be loaded within 2–3 min without sample residue. The process of chip loading with neutral red aqueous solution and digital PCR sample stained with neutral red dye was visualized by microscopy, as shown in Figs. 9(a) and 9(b), respectively. During the surplus sample removal process, it can be observed that the water phase gradually peeled off from the through-hole array chip, and each microsample is partitioned well without obvious droplet on the surface of through-hole array chip. Figure S4 in the supplementary material shows the empty and loaded DFCS-chip. In order to demonstrate the uniformity of the DFCS-chip, the digital PCR sample with no DNA template was loaded onto the chip. The fluorescence intensity of the microsamples under FAM channel was measured by MATLAB. The results are shown in Figs. 9(c) and 9(d). The total number of through-holes was 18 500, and the through-hole filling rate reached 99.10%. The fluorescence intensity of 18 500 microsamples was measured. By comparing mean grayscale value of all measured microsamples, the CV value of each microsample was determined to be about 6.03%, which demonstrates the uniformity of microsamples.

FIG. 9.

Sample loading process and results. (a) Loading process of neutral red dye aqueous solution in an empty DFCS-chip; steps are as follows: inflow of sample, surplus sample removal, and sample partitioning. (b) Loading process of stained digital PCR sample in an empty DFCS-chip. (c) Fluorescence image after sample loading. (d) Statistics of mean grayscale value of each microsample, with insets showing partial magnified fluorescence image and 3D grayscale value. By comparing with the average grayscale values (52) of all measured microsamples, the uniformity of microsamples is demonstrated (CV = 6.03%).

C. Digital PCR amplification

To evaluate the amplification efficiency of the DFCS-chip, we performed digital PCR with target DNA template concentration of 1000 copies/μl on the DFCS-chip. Fluorescence images captured by self-developed platform and the partial magnified fluorescence microscope image under FAM channel are shown in Figs. 10(a) and 10(b). Figure S5 in the supplementary material shows the thermal response of the DFCS-chip in thermal cycling, which means good temperature condition of the microsamples on the chip. After calculating the fluorescence intensity of each through-hole by MATLAB image processing, two distinct peaks appeared in the histogram, as shown in Fig. 10(c). Grayscale value of the negative signals reached 52, and the average grayscale value of the positive signals reached 170, indicating that the microsamples were amplified effectively.

FIG. 10.

Digital PCR results with a target DNA template concentration of 1000 copies/μl. (a) Fluorescence image acquired using a CMOS platform under FAM channel. (b) Fluorescence image acquired by fluorescence microscopy with center wavelength 532 nm of excitation light. (c) Variation of mean fluorescence intensity in each through-hole, where the average value of negative signals reached 52 and the average value of positive signals reached 170.

The absolute quantification of the target DNA template is one of the most important applications of digital PCR. To evaluate the ability of the DFCS-chip to quantitate DNA in a sample, we prepared digital PCR samples with serially diluted DNA templates ranging from 1000 copies/μl to 10 copies/μl to be amplified on the chip; Fig. S6 in the supplementary material shows the quantitative real-time PCR results with a serial dilution of target DNA template. A negative control with no DNA template was additionally loaded onto the chip. Fluorescence images after amplification under the FAM channel are shown in Figs. 11(a)–11(e). With increasing dilution of the target DNA template, the number of positive signals gradually decreased. The negative control did not show any positive signal, indicating that there was no contamination in the samples. What is more, the positive signals in the fluorescence image were scattered, which means that the sample can be well partitioned and remain stable during the thermal cycling. If there was connection between the microsamples, the positive points would tend to aggregate together. The DNA molecules cannot be counted directly by counting the number of positive signals because some microsamples may contain more than one DNA molecule which would result in a nonlinear between positive signals and the number of DNA molecules. Therefore, the actual DNA template concentration was calculated by Poisson statistics according to the following equation:

| (4) |

where m is the dilution factor, f is the number of positive signals, and n is the number of microsamples. After calculation, a linear curve was obtained between expected concentration and measured concentration; this is shown in Fig. 11(f). The R2 value reached 0.999, which demonstrates the feasibility of the DFCS-chip for absolute quantification of DNA.

FIG. 11.

Digital PCR results with different concentrations of wild type JAK2 plasmid DNA. (a)–(d) Digital PCR on the DFCS-chip with a serial dilution of target DNA template:1000 copies/μl, 250 copies/μl, 100 copies/μl, and 10 copies/μl. (e) The negative assay was used as the control with no target DNA template loaded. (f) Regression linear fit between expected concentration (copies/μl) and measured concentration (copies/μl) from the serially diluted samples; the measured value matched well with expected value (R2 = 0.999).

IV. CONCLUSION

In this study, we describe an efficient through-hole array and microfluid-based sample digitization strategy, and we successfully produced a DFCS-chip with high filling rate and uniformity, and zero surplus sample residue. We performed quantitative digital PCR on this chip. The DFCS-chip showed good compatibility with digital PCR and, therefore, has potential for application in techniques such as digital loop-mediated amplification (LAMP) and digital recombinase polymerase amplification (RPA). The number of through-holes can be increased by decreasing the size of the unit and/or increasing the size of the through-hole array chip, and the structure of the channels can be designed based on the dynamic CAs, which will greatly increase the limit of detection. Furthermore, it is possible to design a chip that enables several sample loading processes to be performed in a single operation using microfluidics technology. We are currently working on developing a multiplex digital PCR chip based on our sample digitization strategy. We also try to establish quantitative research methods to study the relationship between sample loading properties and accuracy of results. At present, our strategy still has the limit of large volume of sample loss. We can effectively reduce the sample loss by reducing the height of the flow channel. We are also thinking further about how to adopt a more effective structure to control the phase interface of the sample in the flow channel to reduce the amount of sample loss.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

See the supplementary material for the description, table, and images about the design of the through-hole array; Simulations of the interface of the rhombus-shaped flow channel, hexagon-shaped flow channel, and round-shaped flow channel at an inflow CA of 100°, images of empty and completely loaded DFCS-chip; image of thermal response of the DFCS-chip in “two-step” PCR thermal cycling; image of the quantitative real-time PCR results for FAM channel fluorescence in the JAK2 assay with a serial dilution of wild type template.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (No. 2018YFC0115705), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 51675517, 61874133, and 61901469), the Key Research and Development Program of Jiangsu Province (Nos. BE2018080 and BE2019684), the Jihua Laboratory Foundation (No. X190181TD190), Youth Innovation Promotion Association CAS (Nos. 2019322, 2018360, and Y201856), STS Projects of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (Nos. KFJ-STS-SCYD-217 and KFJ-STS-ZDTP-061), and the Science and Technology Development Program of Suzhou (No. SYG201907).

DATA AVAILABILITY

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- 1.Catarsi P., “Digital PCR—Methods and protocols,” Eur. J. Histochem. 63(4), 251 (2019). 10.4081/ejh.2019.3074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rissin D. M. et al. , “Single-molecule enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay detects serum proteins at subfemtomolar concentrations,” Nat. Biotechnol. 28(6), 595–599 (2010). 10.1038/nbt.1641 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Perez-Ruiz E. et al. , “Digital ELISA for the quantification of attomolar concentrations of Alzheimer's disease biomarker protein Tau in biological samples,” Anal. Chim. Acta 1015, 74–81 (2018). 10.1016/j.aca.2018.02.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ottesen E. A. et al. , “Microfluidic digital PCR enables multigene analysis of individual environmental bacteria,” Science 314(5804), 1464–1467 (2006). 10.1126/science.1131370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cao L. et al. , “Advances in digital polymerase chain reaction (dPCR) and its emerging biomedical applications,” Biosens. Bioelectron. 90, 459–474 (2017). 10.1016/j.bios.2016.09.082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Unger M. A. et al. , “Monolithic microfabricated valves and pumps by multilayer soft lithography,” Science 288(5463), 113–116 (2000). 10.1126/science.288.5463.113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Whale A. S. et al. , “Comparison of microfluidic digital PCR and conventional quantitative PCR for measuring copy number variation,” Nucleic Acids Res. 40(11), e82 (2012). 10.1093/nar/gks203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hindson B. J. et al. , “High-Throughput droplet digital PCR system for absolute quantitation of DNA copy number,” Anal. Chem. 83(22), 8604–8610 (2011). 10.1021/ac202028g [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hindson C. M. et al. , “Absolute quantification by droplet digital PCR versus analog real-time PCR,” Nat. Methods 10(10), 1003–1005 (2013). 10.1038/nmeth.2633 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chu D. et al. , “ESR1 mutations in circulating plasma tumor DNA from metastatic breast cancer patients,” Clin. Cancer Res. 22(4), 993–999 (2016). 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-0943 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guibert N. et al. , “Monitoring of KRAS-mutated ctDNA to discriminate pseudo-progression from true progression during anti-PD-1 treatment of lung adenocarcinoma,” Oncotarget 8(23), 38056–38060 (2017). 10.18632/oncotarget.16935 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barrett A. N. et al. , “Digital PCR analysis of maternal plasma for noninvasive detection of sickle cell anemia,” Clin. Chem. 58(6), 1026–1032 (2012). 10.1373/clinchem.2011.178939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pornprasert S. and Prasing W., “Detection of alpha(0)-thalassemia South-East Asian-type deletion by droplet digital PCR,” Eur. J. Haematol 92(3), 244–248 (2014). 10.1111/ejh.12246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sedlak R. H. et al. , “Clinical utility of droplet digital PCR for human cytomegalovirus,” J. Clin. Microbiol. 52(8), 2844–2848 (2014). 10.1128/JCM.00803-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beer N. R. et al. , “On-chip, real-time, single-copy polymerase chain reaction in picoliter droplets,” Anal. Chem. 79(22), 8471–8475 (2007). 10.1021/ac701809w [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morrison T. et al. , “Nanoliter high throughput quantitative PCR,” Nucleic Acids Res. 34(18), e123 (2006). 10.1093/nar/gkl639 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heyries K. A. et al. , “Megapixel digital PCR,” Nat. Methods 8(8), 649–651 (2011). 10.1038/nmeth.1640 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhu Q. et al. , “Digital PCR on an integrated self-priming compartmentalization chip,” Lab Chip 14(6), 1176–1185 (2014). 10.1039/C3LC51327K [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhu Q. et al. , “A scalable self-priming fractal branching microchannel net chip for digital PCR,” Lab Chip 17(9), 1655–1665 (2017). 10.1039/C7LC00267J [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhu Q. et al. , “Single cell digital polymerase chain reaction on self-priming compartmentalization chip,” Biomicrofluidics 11(1), 014109 (2017). 10.1063/1.4975192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Whitesides G. M., “The origins and the future of microfluidics,” Nature 442(7101), 368–373 (2006). 10.1038/nature05058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Atencia J. and Beebe D. J., “Controlled microfluidic interfaces,” Nature 437(7059), 648–655 (2005). 10.1038/nature04163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stone H. A. et al. , “Engineering flows in small devices: Microfluidics toward a lab-on-a-chip,” Annu. Rev. Fluid Mech. 36, 381–411 (2004). 10.1146/annurev.fluid.36.050802.122124 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xu X. et al. , “High aspect ratio induced spontaneous generation of monodisperse picolitre droplets for digital PCR,” Biomicrofluidics 12(1), 014103 (2018). 10.1063/1.5011240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu W. et al. , “Simultaneous detection of multiple HPV DNA via bottom-well microfluidic chip within an infra-red PCR platform,” Biomicrofluidics 12(2), 024109 (2018). 10.1063/1.5023652 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lindstrom S. and Andersson-Svahn H., “Miniaturization of biological assays - overview on microwell devices for single-cell analyses,” BBA Gen. Subj. 1810(3), 308–316 (2011). 10.1016/j.bbagen.2010.04.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li Z. et al. , “Picoliter well array chip-based digital recombinase polymerase amplification for absolute quantification of nucleic acids,” PLoS One 11(4), e0153359 (2016). 10.1371/journal.pone.0153359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li H. et al. , “Versatile digital polymerase chain reaction chip design, fabrication, and image processing,” Sensor. Actuat. B Chem. 283, 677–684 (2019). 10.1016/j.snb.2018.12.072 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ahrberg C. D. et al. , “Microwell array-based digital PCR for influenza virus detection,” Biochip J. 13(3), 269–276 (2019). 10.1007/s13206-019-3302-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cho H. et al. , “How the capillary burst microvalve works,” J. Colloid. Interf. Sci. 306(2), 379–385 (2007). 10.1016/j.jcis.2006.10.077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Taher A. et al. , “Analytical, numerical and experimental study on capillary flow in a microchannel traversing a backward facing step,” Int. J. Multiphase Flow 107, 221–229 (2018). 10.1016/j.ijmultiphaseflow.2018.06.018 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Conte D. et al. , “Novel method to detect microRNAs using chip-based QuantStudio 3D digital PCR,” BMC Genomics 16, 849 (2015). 10.1186/s12864-015-2097-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Qiu Y. et al. , “High-throughput digital capillary microarray,” Opt. Precis. Eng. 27(6), 1237–1244 (2019). 10.3788/OPE.20192706.1237 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

See the supplementary material for the description, table, and images about the design of the through-hole array; Simulations of the interface of the rhombus-shaped flow channel, hexagon-shaped flow channel, and round-shaped flow channel at an inflow CA of 100°, images of empty and completely loaded DFCS-chip; image of thermal response of the DFCS-chip in “two-step” PCR thermal cycling; image of the quantitative real-time PCR results for FAM channel fluorescence in the JAK2 assay with a serial dilution of wild type template.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.