Abstract

Drought is one of the major constraints in wheat production and causes a huge loss at grain-filling stage. In this study we highlighted the response of different wheat genotypes under drought stress at the grain-filling stage. Field experiments were conducted to evaluate 72 wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) genotypes under two water regimes: irrigated and drought condition. Four wheat genotypes, two each of drought tolerant (IC36761A, IC128335) and drought-susceptible category (IC335732 and IC138852) were selected on the basis of agronomic traits and drought susceptibility index (DSI), to understand their morphological, biochemical and molecular basis of drought stress tolerance. Among agronomic traits, productive tillers followed by biomass had high percent reduction under drought stress, thus drought stress had a great impact. Antioxidant activity (AO), total phenolic and proline content were found to be significantly higher in IC128335 genotype. Differential expression pattern of transcription factors of ten genes revealed that transcription factor qTaWRKY2 followed by qTaDREB, qTaEXPB23 and qTaAPEX might be utilized for developing wheat varieties resistant to drought stress. Understanding the role of TFs would be helpful to decipher the molecular mechanism involved in drought stress. Identified genotypes (IC128335 and IC36761A) may be useful as parental material for future breeding program to generate new drought-tolerant varieties.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s13205-020-02264-8) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Antioxidant activity, Drought, DSI, SOD, Triticum aestivum, Wheat

Introduction

Plants encounter various kinds of abiotic stresses namely salinity, cold stress, heat stress and drought. These are the major stresses causing reduction in crop yield worldwide and is one of the major threat to food security due to continuous change of climate and environment deterioration caused by human interference. Whenever surrounding environmental conditions deviate from the optimum conditions required for the growth and development of crops, crops experiences the effects of abiotic stress (Larcher 2003). Plants have different mechanism to cope up with the stress occurred. Plants overcome such stresses by altering their morphology, modifying various internal compounds and controlling the expression of set of drought-resistant genes to fight against the drought stress and also by minimizing the degree of self damage (Li et al. 2020). Drought is one of the most frequently encountered abiotic stress which effects growth and productivity of various plants, including wheat (Campbell et al. 2016; Lipiec et al. 2013; Lesk et al. 2016).

Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) is the most important food grain cereal in the world, accounting for more than half of the world’s total food consumption (Qin et al. 2012). Bread wheat is hexaploid, with a estimated genome size of ~ 17 Gb i.e. about 100, 40 and 6 fold to the arabidopsis, rice and maize genome, respectively (Bennett and Smith 1976; Arumuganathan and Earle 1991). Research studies published between 1980 to 2015 reported yield reduction from 21 to 40% due to drought stress at global scale in wheat and maize (Daryanto et al. 2016). Further, drought has been gaining attention in the last few years due to global warming (Kang et al. 2009). Wheat growth is affected by drought at different stages i.e. phenological, reproductive and grain-filling phases (Pradhan et al. 2012). In T. aestivum terminal drought stress has negative impact on grain filling and it also severely hampers the grain-filling rate due to reduction in photosynthesis rate, accelerated leaf senescence, and sink limitations (Madani et al. 2010; Wei et al. 2010). (Fleury et al. 2010; Matiu et al. 2017) showed that mild drought at post anthesis, decreases wheat yield by up to 1–30%, whereas a prolonged mild drought during the flowering and grain-filling stages causes up to 58–92% reduction in grain yield. Whole genome sequencing of wheat has opened the new avenues for wheat researchers to study the possible role of different genes and transcription factors in regulating gene expression and associated pathways (Appels et al. 2018). Generally, crops respond to abiotic stress by adopting various mechanisms i.e. from the molecular to the morphological (Bohnert 2007). Water deficit stress (WDS) responses are most quantitative and multigenic with strong adverse environmental effects on crop phenotypes. However, limited information is available on response to drought at molecular level during grain-filling stage in wheat. Improvement of modern cultivars for drought tolerance is essential to identify plants exhibiting high water deficit tolerance as they can serve as the donors of drought-related genes and gene regions. Also, there is a need to identify the candidate genes (transcription factors) associated with tolerance response against terminal drought and further investigate their molecular mechanism. This information will be useful for breeders to ameliorate the local cultivars in terms of the resistance.

Plants have the mechanism to sustain in the harsh conditions by increasing the antioxidant enzymes and redox metabolites to protect cells from oxidative stress (Sairam and Tyagi 2004; Devi et al. 2012).The immediate signals of abiotic stresses are transduced through increased levels of Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS), such as singlet oxygen (1O2), superoxide anion radical (), hydroxyl radical (OH⋅) and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) (Reczek and Chandel 2015). There are two mechanisms to scavenge ROS generated during the stress viz. scavenged by non-enzymatic (ascorbate, tocopherols, glutathione, salicylate) and enzymatic antioxidants such as, superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase, ascorbate peroxidase (Foyer and Noctor 2003; AbdElgawad et al. 2016). Under abiotic stress conditions, osmolytes (proline and soluble sugars) protect plants from cellular damage (Gharsallah et al. 2016). Previous studies revealed the role of drought mediated upregulation of antioxidative enzymes in wheat (Devi et al. 2012; Hassan et al. 2015). Phenolic compounds also play an important role in quenching of ROS. Biosynthesis and accumulation of polyphenolic compounds are generally accelerated during abiotic and biotic stress conditions (Valifard et al. 2014).

Drought tolerance is a very complex phenomenon which involves various molecular and physiological mechanisms (Farooq et al. 2009; Pereira et al. 2011). Transcription factors act as the key regulators of gene expression during abiotic and biotic stresses. Characterization and expression analysis studies of TFs have well proven their importance in stress tolerance. The TFs family, WRKY, not only has role in abiotic stresses tolerance, but also regulates plant growth and development process (Jiang et al. 2012; Zhu et al. 2013; Tripathi et al. 2014). The transcription factor, DREB1A, has been reported to accelerate stress tolerance response of plants against drought stress (Ravikumar et al. 2014). Apart from these some other TF e.g. NAC2a, EXPB23, and MYB 33, TFs are also reported to be involved in various abiotic and biotic stress responses (Xia et al. 2010). Understanding the role of TFs would be helpful to decipher the molecular mechanism involved in drought stress. Therefore, the aim of present work was to understand the morphological, biochemical and molecular mechanisms associated with drought tolerance in contrasting wheat genotypes.

Materials and methods

Plant material

A set of 72 wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) genotypes procured from ICAR-Indian Institute of Wheat and Barley Research (ICAR-IIWBR), Karnal, India were used in the present study (Table 1) for screening under two different contrasting conditions i.e. irrigated and drought.

Table 1.

Pedigree details of studied 72 wheat genotypes

| Genotype | Pedigree | Genotype | Pedigree |

|---|---|---|---|

| AKW2862-1 | VEE#6//DOVE"S"/BUC"S" CM92225-66Y-OM | HGP1-359 | HD2808/HUW510 (359) |

| C306 | RGN/CSK3//2*C591/3/C217/N14//C281 | 11-F1-16 | RAJ4014/HUW510 |

| C306 M10 | C306 irradiated with Co60 source (mutant) | 11-F1-3 | K7903/P11632 |

| HINDI 62 | landrace from UP (IC296681) | 11-F1-8 | HD2808/RAJ4014 |

| HTW6 | Germplasm collection | 11-F1-2 | K7903/RAJ4014 |

| HTW11 | Germplasm collection | IC138852 | Germplasm collection |

| IC28658 | Germplasm collection | UAS 320 | UAS257//GW322/DWR195 |

| IC28665 | Germplasm collection | HGP1-107 | HD2808/HUW510 (107) |

| IC31488 | Germplasm collection | HGP1-315 | HD2808/HUW510 (315) |

| IC57985 | Germplasm collection | HGP1-31 | HD2808/HUW510 (31) |

| IC78856 | Germplasm collection | J31-33 | RAJ3765/P11632(33) |

| IC128335 | Germplasm collection | HGP1-452 | HD2808/HUW510 (452) |

| IC28692A | Germplasm collection | HGP1-20 | HD2808/HUW510 (20) |

| IC59128B | Germplasm collection | HGP1-448 | HD2808/HUW510 (448) |

| IC78094B | Germplasm collection | HGP1-455 | HD2808/HUW510 (455) |

| J31-73 | RAJ3765/P11632 (73) | HGP1-208 | HD2808/HUW510 (208) |

| F1-5 | HD2808/K7903 | HGP1-305 | HD2808/HUW510 (305) |

| J31-45 | RAJ3765/P11632 (45) | J31-23 | RAJ3765/P11632 (23) |

| J31-80 | RAJ3765/P11632 (80) | J31-83 | RAJ3765/P11632 (83) |

| J31-102 | RAJ3765/P11632 (102) | J31-170 | RAJ3765/P11632 (170) |

| J31-2 | RAJ3765/P11632 (2) | J31-24 | RAJ3765/P11632 (24) |

| J31-101 | RAJ3765/P11632 (101) | IC416188 | Germplasm collection |

| J31-165 | RAJ3765/P11632 (165) | IC59575 | Germplasm collection |

| HGP1-318 | HD2808/HUW510 (318) | IC443636 | Germplasm collection |

| J31-145 | RAJ3765/P11632 (145) | IC445365 | Germplasm collection |

| HGP1-306 | HD2808/HUW510 (306) | IC335732 | Germplasm collection |

| HGP1-460 | HD2808/HUW510 (460) | IC279617 | Germplasm collection |

| HGP1-81 | HD2808/HUW510 (81) | IC128218 | Germplasm collection |

| HGP1-403 | HD2808/HUW510 (403) | IC539602 | Germplasm collection |

| HGP1-32 | HD2808/HUW510 (32) | IC539525 | Germplasm collection |

| HGP1-385 | HD2808/HUW510 (385) | IC536375 | Germplasm collection |

| HGP1-468 | HD2808/HUW510 (468) | IC416108 | Germplasm collection |

| HGP1-470 | HD2808/HUW510 (470) | IC535706 | Germplasm collection |

| HGP1-435 | HD2808/HUW510 (435) | IC36761A | Germplasm collection |

| HGP1-180 | HD2808/HUW510 (180) | WH1123 | NI5663/RAJ3765//K9330 |

| J31-43 | RAJ3765/P11632 (43) | WH1126 | WBLL1*2/VIVITSII |

Field experiment

Field experiments were conducted at the ICAR-IIWBR, Karnal, India during 2015–16 and 2016–17, rabi seasons in two replications. Trials were conducted in two sets: under drought conditions in rainout shelter and under irrigated conditions under field condition. Agronomic traits viz, days to heading, days to anthesis, days to maturity, grain-filling duration, plant height (cm), productive tillers, grain yield/m2 (g), no of spikelets/spike, spike length (cm), grain number/spike, grain weight/spike, 1000-grain weight and biomass/m2 (g) were recorded. Drought susceptibility index (DSI) and harvest index (%) for each genotype were estimated. DSI is a measure of stress resistance based on minimization of yield loss under stress compared to optimum conditions. Out of 72, four most drought-responsive Triticum aestivum genotypes, both drought susceptible (IC138852 and IC335732) and drought tolerant (IC128335 and IC36761) were selected and subjected for biochemical and molecular examination. It has been observed that these genotypes were stable for response to drought stress over the years. Shoot samples were collected at grain-filling stage, rinsed in distilled water, dried (using filter paper), frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80 °C for further biochemical and tissue-specific expression pattern profiling.

Estimation of lipid peroxidation

Lipid peroxidation (LP) was estimated (as MDA level) in shoot tissues following the procedure described by (Cakmak and Horst 1991). Fresh tissue (1 g) was ground in 20 mL of 0.1% tri-chloro acetic acid (TCA) solution, followed by centrifugation (12,000g, 10 min). Supernatant (1 mL) was mixed with 4 mL of 20% TCA comprising 0.6% thiobarbituric acid (TBA), the mixture was heated at 95 °C for 30 min, and then cooled in ice. The content was centrifuged again, and absorbance was recorded at 532 and 600 nm. The reading of MDA level was calculated in triplicates and average mean of the reading was used with extinction coefficient of 155 mM−1 cm−1 and same can be expressed as using following formula:

Estimation of antioxidant activity

Antioxidant activity (AO) in tissue extract was measured using stable diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) radical according to (Hatano et al. 1988). Alcoholicsolution of DPPH radical (0.5 mL, 0.2 mM) was added to the 100 μL of the extract, incubated in dark for 30 min, and absorbance was recorded at 517 nm. Capacity to scavenge DPPH was calculated using the following formula:

(where, A0 is the absorbance of control reaction, and A1 is that of the sample).

Estimation of total phenolic content

To estimate the stress-induced variation in production of secondary metabolites, total phenolic content (TPC) was estimated following the approach of (Singleton et al. 1999). To aqueous extract of the sample (0.5 mL), 2.5 mL Folin-Ciocalteu reagent (10% v/v), 2 mL sodium carbonate (7.5%) was added, the mixture was incubated at 45 °C for 40 min, and absorbance was measured at 765 nm. Gallic acid was used to prepare standard curve, TPC was calculated from the mean value, and expressed as mg g−1 of gallic acid equivalent (GAE) fresh weight (FW).

Estimation of proline content

Proline content in the sample was determined according to (Bates et al. 1973) using Ninhydrin reagent. Sample tissue was homogenized in 3% aqueous sulfosalicylic acid and filtered through whatmann filter paper (Grade 1). To the supernatant, equal volume of glacial acetic acid and ninhydrin were added, and absorbance was measured at 520 nm. Proline content in sample was estimated from the standard curve of proline.

Activity assay of antioxidant enzyme

Extraction and activity assay of antioxidant enzymes, viz. superoxide dismutase (SOD), peroxidase (POX) and glutathione reductase (GR),were performed by homogenizing 1 g of tissue in 5 mL extraction medium (0.1 M phosphate buffer + 0.5 mM EDTA, pH 7.5) following the approach of (Singh and Laxmi 2015). The homogenate was filtered with whatmann filter paper (Grade 1) and centrifuged at 4 °C (15,000g, 20 min). Total protein content was estimated by Bradford method using BSA as standard, and the specific activity (U mg−1 protein) was determined.

Determination of chlorophyll concentration

Total chlorophyll content in leaf tissues was estimated using dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) method (Hiscox and Israelstam 1979) For this, 500 mg of leaf sample was cut into small pieces with the help of scalpel blade and the pieces were suspended in 2 mL DMSO in a test tube. The test tubes were incubated at 60 °C for 20 min in a water bath. The chlorophyll extract was collected by decanting and another 2 mL of DMSO was added to the residual leaf tissues and further incubated at 60 °C for 20 min. The chlorophyll extracts were pooled together and the volume was made up to 10 mL with DMSO. Absorbance of the chlorophyll extract was taken at 663 and 645 nm against DMSO blank using spectrophotometer (Thermo scientific, Evolution 220). Total chlorophyll content was calculated on the basis of fresh weight (FW) using the following formula (Arnon 1949):

RNA isolation and cDNA preparation

Total RNAs were extracted from 100 mg of shoot tissues of drought susceptible (IC138852 and IC335732)—and drought susceptible (IC128335 and IC36761)- genotypes using RNeasy Plant Mini kit (50) from Qiagen (Hilden, Germany), and first-strand cDNA was synthesized using verso cDNA synthesis kit from Thermo Scientific (Lithuania, Europe) as per the manufacturer’s instructions. To investigate the temporal expression patterns of ten stress-responsive genes/TFs, selected based on information available in literature by qRT-PCR analysis. These 10-target stress-responsive genes/TFs (qTaDREB, qTaEXPB23, qTaHSP20, qTaWRKY2, qTaNAC2a, qTaMYB33, qTaHSP-sti, qTaHSP90, qTaHSP40 and qTaAPEX) are known to have significant role in amelioration of drought stress in wheat as well as other crops. To design gene-specific primers, the sequences were from the sequences downloaded from Grain genes (database for Triticeae and Avena), NCBI database (Table 4). As we know that wheat is a polyploidy genome and contains multiple copies of the genes selected in this study. primers designed with the parameters including:(1) at least 2 variant site in the primer and (2) flanking 200 bp of the hit sequence for alignment. Then the selected forward and reverse sequences was further confirmed by Primer BLAST to design gene-specific primers from the exonic region by setting the minimum and maximum intron length parameters for all the transcription factors used in expression analysis study. The designed gene-specific primers were custom synthesized from Integrated DNA Technologies, USA.

Table 4.

Primer sequences used in mRNA expression analysis

| Transcription factors | Forward primer | Reverse primer | Accession number |

|---|---|---|---|

| qTaNAC2a | 5′ TCAGCTACGACGACATCCA 3′ | 5′ CGAAGAGGGAGGAGTAGAG 3′ | HM027577.1 |

| qTaDREB | 5′ TGGAATGGCGTGGAGATTG 3′ | 5′ TCTGATATCCACATTGGGTAAGG 3′ | AY781351.1 |

| qTaHsp40 | 5′ GCAAATGCTATGCAGCTCTCCTCA 3′ | 5′ AAGGTGCAGACAAGCCTCCTACAT 3′ | KM017976.1 |

| qTaHsp40 | 5′ GCAAATGCTATGCAGCTCTCCTCA 3′ | 5′ AAGGTGCAGACAAGCCTCCTACAT 3′ | KM017976.1 |

| qTaMyb | 5′ GCTTTACATCGGAGGAGTTTCA 3′ | 5′ CTGAGACAAACTCTGCACCT 3′ | KT033413 |

| qTaHsp90 | 5′ AACATGGAGAGGATCACGAAG 3′ | 5′ CTGAATCCAGAGGTGAGCAG 3′ | MF383197 |

| qTapAPX | 5′ CTGAAGATCCCTACTGATAAGG 3′ | 5′ GCACTCTGTGCAAGTACAAC 3′ | JX126968 |

| qTaHsp-Sti | 5′ GATGGTATCAGGAGGTGTGTTG 3′ | 5′ GTTTGGACTATTCCAGCGTTTATG 3′ | HM998695.1 |

| qTaWRKY2 | 5′ GACGCTGAGCGATATAGACATAC 3′ | 5′ ACCGTTGTGCACTTGTAGTAG 3′ | EU665425.1 |

| qTaEXPB23 | 5′ TCATCGACATCCAGTTCAAGAG 3′ | 5′ CAGCACCGCGAAGTACA 3′ | AY260547.1 |

| qTaHsp20 | 5′ CAACACGGACCCAAATCCACACTT 3′ | 5′ CGGAGGTCAAGTCCATCCAGATTT 3′ | HC751303.1 |

| qTaActin | 5′ AGCTCGCATATGTGGCTCTT 3′ | 5′ CCAGCAGCTTCCATACCAAT 3′ | AB181991.1 |

Quantitative real-time PCR (RT-qPCR) analysis

RT-qPCR analysis for each candidate gene was carried out in three biological and 3 technical replications. Starting with equal amount of RNAs from the samples, 1 µL (concentration) of the first-strand cDNA was used in 20 µL qPCR mix containing 10 picomol of forward and reverse primers following the procedure described by (Singh and Laxmi 2015). To estimate relative gene expression, Ct value for the target and reference genes were calculated using mean of the replications. Actin gene was used as a reference gene, and Pfaffl formula (ratio = ) was used to calculate the relative fold expression.

Statistical analysis

The experimental data were analyzed using statistical software, SPSS 19.0. Fischer’s least significant difference (LSD) was used to determine significant difference between the treatment means at a significance level of P-value < 0.05.

Gene annotation and classification

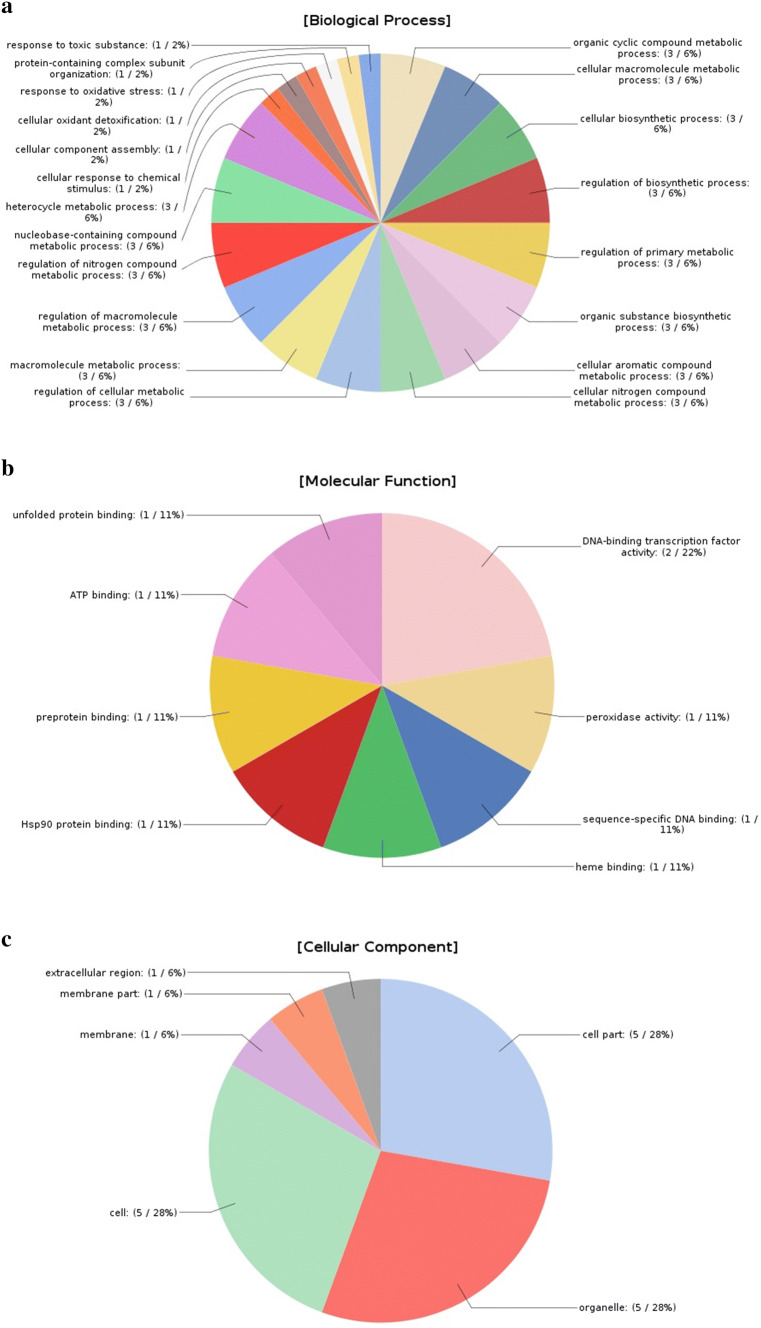

To perform functional annotation of 8 TFs (Transcription Factors), all the accessions were downloaded from NCBI (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) public repository. Further, analysis of TF for identification of gene ontology (GO) terms (biological, molecular and cellular processes) (S1 & S2 A, B & C) performed using BLAST2GO software (v5.2.5) (https://www.blast2go.com/) at default parameters.

Results

Selection of contrasting drought tolerant and susceptible genotypes

Field experiment was conducted using 72 genotypes under drought and irrigated condition. Pooled analysis of the experimental data over two seasons showed highly significant differences among wheat genotypes for all the studied traits viz; days to heading, days to anthesis, days to maturity, grain-filling duration, plant height (cm), productive tillers, grain yield (g), no of spikelets/spike, spike length (cm), grain number/spike, grain weight/spike, 1000-grain weight, and harvest index. It has been observed that these traits are significantly affected by drought stress. Summary statistics for all the traits under study are presented in Table 2. Percent reduction was maximum in productive tiller number, followed by biomass and grain yield (Table 3). Drought Susceptibility Index (DSI) of genotypes were estimated on the basis of changes in grain yield (GY) under drought stress, and five topmost tolerant and susceptible genotypes were selected for further study (Table 3). Based on Drought Susceptibility Index (DSI) from −0.39 to 0.59, genotypes IC36761A, C306, IC128335, IC59575 and IC28658 were considered as the drought-tolerant genotypes and, drought-susceptible genotypes, as 11-F1-8, HGP1-435, J31-2, IC138852 and IC335732 with DSI ranges from 1.20 to 1.56 (Table 3). Based on mean performance under stress, genotypes with DSI < 0.5 were selected as drought tolerant and genotypes with DSI > 1 were adjudged as drought susceptible. Accordingly, IC36761A (− 0.39) and IC128335 (0.48) were considered as tolerant genotypes and IC335732 (1.56) and IC138852 (1.40) with the highest DSI were considered as drought-susceptible genotypes.

Table 2.

Mean agronomic performance of genotypes over the years under irrigated and drought conditions

| DH | DA | DM | GFD | PHT | PTL | BM | GY | GN | GW | TGW | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Irrigated condition | |||||||||||

| Mean | 88.0 | 97.2 | 135.2 | 41.4 | 109.5 | 109.3 | 713.4 | 328.6 | 50.4 | 2.10 | 43.70 |

| SD | 7.3 | 6.6 | 2.9 | 4.7 | 12.6 | 13.1 | 151.2 | 50.5 | 7.2 | 0.40 | 4.34 |

| CV% | 8.3 | 6.8 | 2.2 | 11.5 | 11.5 | 12.0 | 21.2 | 15.4 | 14.4 | 19.05 | 9.94 |

| SE | 0.9 | 0.8 | 0.3 | 0.6 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 17.8 | 5.9 | 0.9 | 0.05 | 0.51 |

| Rainout shelter condition | |||||||||||

| Mean | 78.0 | 86.3 | 122.9 | 40.1 | 93.9 | 63.4 | 416.1 | 198.9 | 49.3 | 1.90 | 38.10 |

| SD | 6.4 | 5.4 | 3.0 | 3.8 | 11.5 | 9.5 | 95.1 | 32.6 | 7.1 | 0.30 | 2.95 |

| CV% | 8.2 | 6.2 | 2.4 | 9.6 | 12.3 | 14.9 | 22.8 | 16.4 | 14.5 | 15.78 | 7.74 |

| SE | 0.8 | 0.6 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 1.4 | 1.1 | 11.2 | 3.8 | 0.8 | 0.04 | 0.35 |

| % reduction | 11.33 | 11.20 | 9.07 | 3.18 | 14.27 | 41.96 | 41.67 | 39.47 | 2.11 | 9.52 | 12.81 |

DH days to heading, DA days to anthesis, DM days to maturity, GFD grain-filling duration, PHT plant height (cm), PTL productive tillers, BM biomass, GY grain yield (g/m2), GN grain number/spike, GW grain weight/spike, TGW thousand grain weight (g)

Table 3.

List of five most tolerant and five most susceptible genotypes based on grain yield over the years and their mean agronomic performance under irrigated and drought conditions

| Genotype | Conditions | DH | DA | DM | GFD | PHT | PTL | BM | GY | GN | GW | TGW | DSI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Top five tolerant genotypes | |||||||||||||

| HTW63 | IR | 84.25 | 91.75 | 132.00 | 44.00 | 135.58 | 126.00 | 775.90 | 270.83 | 43.02 | 1.60 | 37.17 | -0.39 |

| HTW63 | RF | 73.50 | 82.50 | 121.75 | 43.75 | 111.83 | 67.3 | 500.4 | 311.9 | 38.0 | 1.5 | 39.8 | |

| C 306 | IR | 90.75 | 101.75 | 138.50 | 40.25 | 124.33 | 111.50 | 676.00 | 208.70 | 47.92 | 1.95 | 40.62 | 0.34 |

| C 306 | RF | 83.00 | 89.75 | 125.25 | 38.25 | 114.17 | 69.1 | 350.5 | 181.4 | 47.7 | 2.1 | 44.1 | |

| DTW64 | IR | 93.50 | 102.75 | 138.50 | 37.50 | 127.67 | 106.88 | 252.37 | 207.27 | 43.08 | 1.81 | 41.83 | 0.48 |

| DTW64 | RF | 82.00 | 88.75 | 125.50 | 39.50 | 113.67 | 64.0 | 325.6 | 168.8 | 46.4 | 2.0 | 44.2 | |

| HTW47 | IR | 90.75 | 101.50 | 139.50 | 41.25 | 119.50 | 112.50 | 751.06 | 289.62 | 43.18 | 1.48 | 34.60 | 0.54 |

| HTW47 | RF | 79.25 | 85.75 | 125.25 | 42.25 | 106.58 | 71.8 | 300.5 | 229.1 | 40.2 | 1.8 | 44.9 | |

| DTW54 | IR | 90.50 | 100.00 | 136.50 | 39.25 | 125.00 | 117.88 | 501.00 | 278.28 | 40.18 | 1.60 | 38.10 | 0.59 |

| DTW54 | RF | 84.50 | 91.00 | 126.00 | 37.25 | 120.58 | 77.5 | 450.6 | 214.3 | 50.1 | 2.1 | 41.4 | |

| Bottom five susceptible genotypes | |||||||||||||

| HTW50 | IR | 97.50 | 104.00 | 139.50 | 45.00 | 111.42 | 102.13 | 751.10 | 352.07 | 49.10 | 2.40 | 49.01 | 1.56 |

| HTW50 | RF | 86.50 | 92.25 | 128.50 | 39.25 | 96.75 | 40.6 | 250.3 | 137.9 | 45.6 | 2.2 | 48.9 | |

| HTW35 | IR | 86.00 | 94.50 | 132.00 | 42.50 | 134.33 | 98.13 | 551.08 | 274.83 | 64.75 | 2.92 | 45.16 | 1.40 |

| HTW35 | RF | 78.75 | 86.00 | 121.75 | 43.50 | 109.33 | 61.3 | 250.5 | 124.4 | 57.9 | 2.5 | 44.0 | |

| HTW16 | IR | 83.00 | 94.50 | 133.50 | 43.50 | 97.42 | 120.88 | 1000.99 | 334.47 | 46.73 | 1.80 | 39.24 | 1.23 |

| HTW16 | RF | 71.25 | 85.00 | 121.00 | 41.00 | 85.67 | 68.9 | 475.6 | 173.5 | 45.0 | 2.1 | 46.3 | |

| HTW28 | IR | 86.75 | 94.50 | 133.25 | 42.25 | 99.08 | 128.00 | 925.94 | 391.36 | 46.23 | 1.67 | 36.12 | 1.23 |

| HTW28 | RF | 79.00 | 85.75 | 122.50 | 40.00 | 77.08 | 52.3 | 275.4 | 204.3 | 47.1 | 2.0 | 43.6 | |

| HTW33 | IR | 85.75 | 94.50 | 136.25 | 45.00 | 118.33 | 112.00 | 425.84 | 267.82 | 48.08 | 1.70 | 35.64 | 1.20 |

| HTW33 | RF | 77.75 | 84.25 | 126.25 | 45.00 | 99.92 | 61.1 | 225.4 | 142.3 | 47.2 | 1.9 | 39.8 | |

IR irrigated, RF rainfed, DH days to heading, DA days to anthesis, DM days to maturity, GFD grain-filling duration, PHT plant height (cm), PTL productive tillers, BM biomass, GY grain yield (g/m2); GN grain number/spike, GW grain weight/spike, TGW thousand grain weight (g), DSI drought susceptibility index

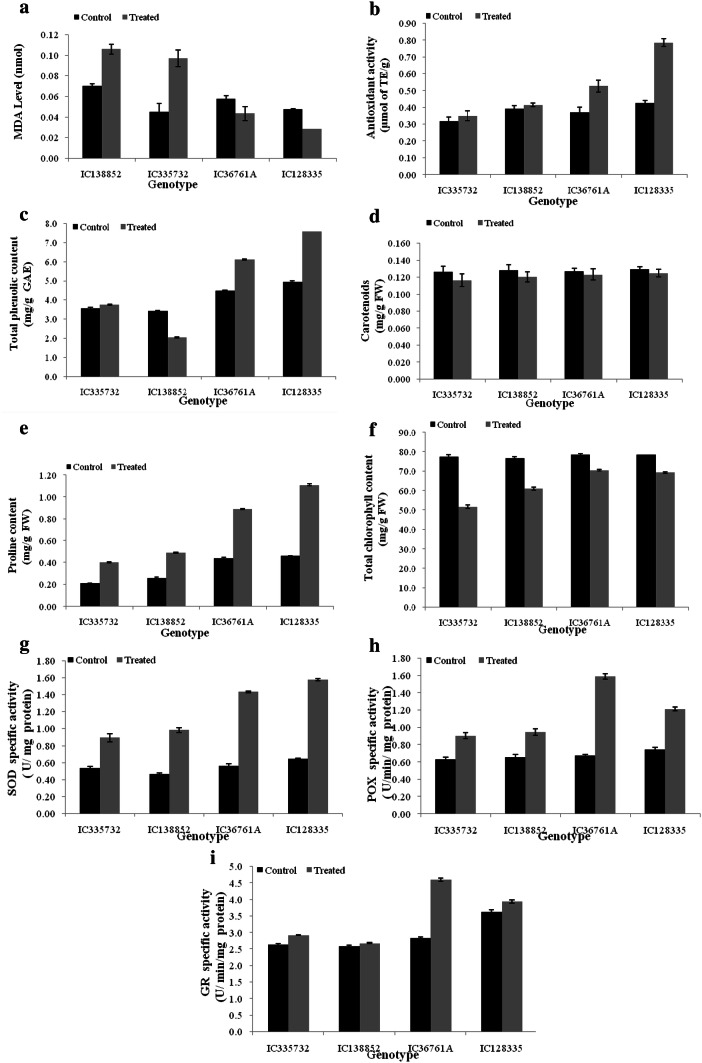

Differential effects of drought stress on biochemical activities

Lipid peroxidation

Lipid peroxidation (LP) was carried out in shoot tissues which were collected at the grain-filling stage from irrigated and non-irrigated conditions. Lipid peroxidation (LP) in the shoot tissues (measured in terms of MDA level) was observed to increase in the drought-susceptible genotypes under stress, while it decreased in case of the drought-tolerant genotypes (Fig. 1a). Increase in LP was observed in the shoot tissues of the drought-susceptible genotypes under stress with maximum in case of IC138852 (1.6-fold). Amongst drought-tolerant genotypes, the maximum decrease in LP, under the stress of was observed in IC36761A (1.3 fold).

Fig. 1.

Variation in biochemical parameters/enzymatic activities in the shoots of contrasting wheat genotypes: drought-sensitive (IC138852 and IC335732) and drought-tolerant (IC36761A and IC128335). a Lipid peroxidation, b antioxidant activity, c total phenolic content, d carotenoid content, e proline content, f total chlorophyll content, g SOD, h POX and i GR. Bars indicate standard error of mean

Antioxidant activity

Increase in the scavenging of DPPH or antioxidant activity (AO) in the shoot tissues of contrasting genotypes was observed under drought stress (Fig. 1b). However, the basal level (under control condition), as well as the increase in AO due to drought stress, was found to be considerably higher in case of drought-tolerant genotypes. IC335732 showed the lowest AO (1.1 fold) followed by IC138852 (1.05 fold), while IC128335 exhibited the highest AO (1.8 fold) followed by IC36761A (1.4 fold), under the imposed drought conditions. Comparative analysis indicated that drought-susceptible genotypes had lower AO than the drought-tolerant genotypes irrespective of the condition (control or drought stress) of growth.

Total phenolic content

The total phenolic content (TPC) in the shoot tissues of drought-susceptible genotypes have been significantly reduced under drought stress. On the other hand, increase in TPC was observed in the drought-tolerant genotypes. The highest level of TPC was found in IC128335 followed by IC36761A and maximum increase in TPC (1.6-fold) due to stress (Fig. 1c). Reduction of TPC was recorded in IC138852 (1.7-fold), and minor increase in TPC was found in one of the susceptible genotypes (IC335732).

Carotenoids

Carotenoid content was found to be comparable in all the four genotypes under controlled condition; however, drought stress causes significant reduction in level of carotenoid in all four genotypes as compared to their respective controls. Highest reduction in carotenoid (1.1-fold) content was found in drought-susceptible genotype (IC335732) (Fig. 1d).

Proline content

Comparative analysis of the most contrasting genotypes (i.e. IC138852, IC335732—drought susceptible and IC128335, IC36761A-drought tolerant) revealed that there was a significant increase in the proline content on imposition of drought in all the four genotypes (Fig. 1e). However, the increase was prominent in case of IC128335 (2.4-fold).

Total chlorophyll content

Total chlorophyll content was found to be comparable in all the four genotypes under controlled condition; however, drought stress causes significant reduction in level of total chlorophyll content in all four genotypes as compared to their respective controls. Highest reduction in total chlorophyll content (30%) was found in drought-susceptible genotype (IC335732) (Fig. 1f).

Effect of drought stress on enzymatic activities

Antioxidant enzymes

The activity of the antioxidant enzymes (SOD, POX, and GR) were found to increase under stress. The SOD activity was more or less the same under control condition in all the genotypes except in IC138852 where the SOD activity was less as compared to other genotypes. More increase in the activity of SOD was observed in drought-tolerant genotype IC128335 (Fig. 1g). POX activity was found to be maximum in IC36761A (2.3-fold) after drought stress imposition (Fig. 1h). GR activity was found to increase in all the genotypes after drought stress; however, increase in GR activity was not prominent in the susceptible genotypes. IC36761A showed maximum GR activity (1.6-fold) after drought stress imposition (Fig. 1i).

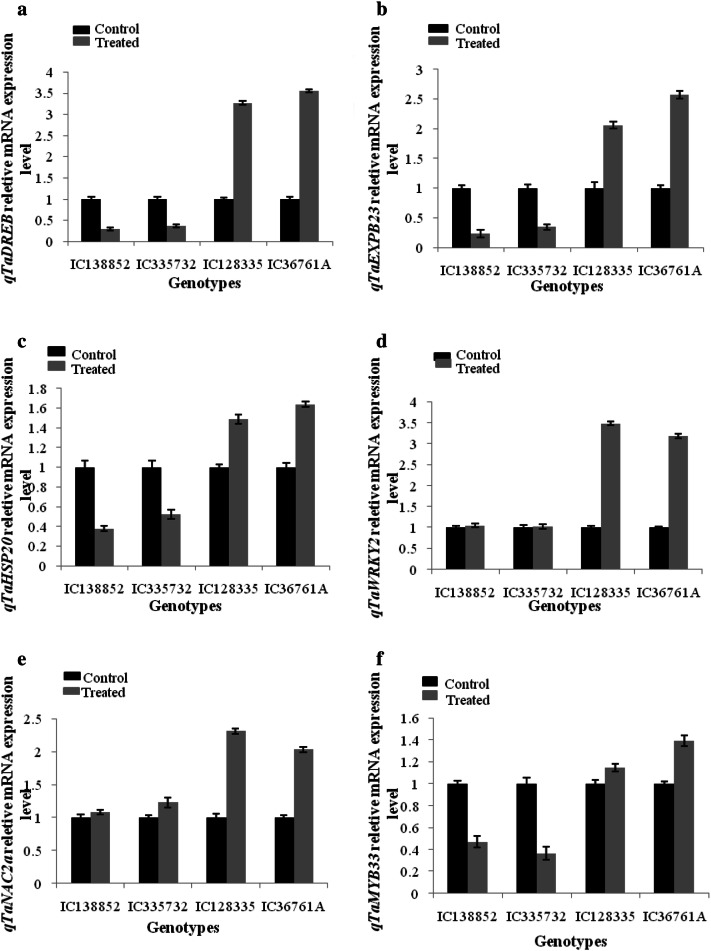

Expression of TFs associated with drought tolerance

RT-qPCR analysis of the drought-responsive transcription factors was carried out in shoot tissue of all the wheat genotypes (Fig. 2a–j). The expression level of reference gene (actin) was uniform in all the shoot tissues. Primers used for differential expression study of transcription factors are given in the (Table 4). The expression level of ten different TFs was studied in shoot tissues of contrasting wheat drought genotypes after drought stress imposition. Out of ten TFs five showed significant change in their expression after drought stress. qTaDREB were highly up regulated in drought-tolerant genotypes as compared to susceptible one. Among tolerant genotypes IC128335 showed 3.26 fold and IC36761A showed 3.55 fold while in susceptible 0.29 and 0.37 fold change was observed in IC138852 and IC335732 genotypes, respectively, as compared to control. qTaEXPB23 and qTaAPEX were found to be down regulated in susceptible and upregulated in tolerant genotypes. qTaWRKY2 showed higher fold changes in drought-tolerant genotypes after drought imposition 3.49 fold and 3.20 fold change in IC128335 and IC36761A, respectively, while less variation was observed in susceptible genotypes. qTaNAC2a TF was found to be down regulated in drought-susceptible genotypes 1.08 fold and 1.23 fold change in IC138852 and IC335732 and up regulated by 2.31 fold and 2.03 fold change in drought-tolerant genotypes IC128335, IC36761A, respectively.

Fig. 2.

Expression of transcription factors qTaDREB (a), qTaExpb23 (b), qTaHSP20 (c), qTaWRKY2 (d), qTaNAC2a (e), qTaMyb33 (f), qTaHSP-sti (g), qTaHSP90 (h), qTaHSP40 (i) and qTaAPX (j) in drought susceptible and tolerant wheat genotypes. The transcript level of these two genes was normalized to actin expression. Each bar represents the mean from three independent experiments with standard error of mean

qTaWRKY2 showed higher fold changes in drought-tolerant genotypes after drought imposition 3.49 fold and 3.20 fold change in IC128335 and IC36761A, respectively, while less variation was observed in susceptible genotypes.

qTaNAC2a TF was found to be down regulated in drought-susceptible genotypes 1.08 fold and 1.23 fold change in IC138852 and IC335732 and up regulated by 2.31 fold and 2.03 fold change in drought-tolerant genotypes IC128335, IC36761A, respectively.

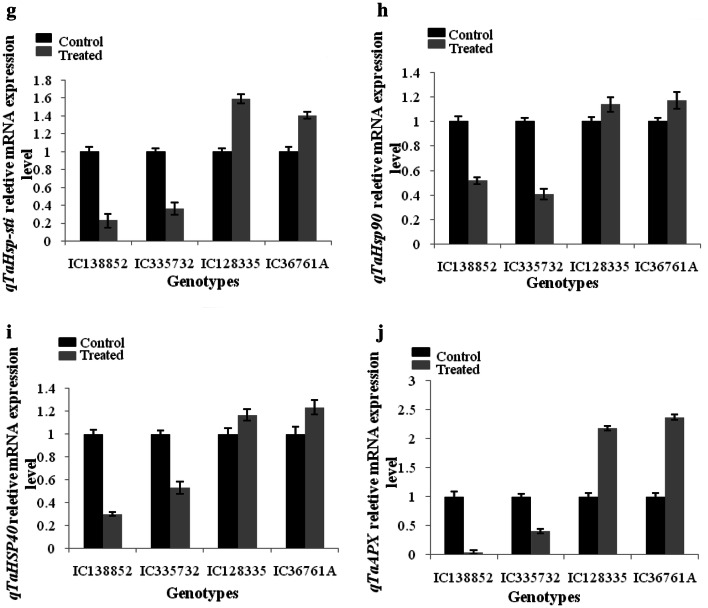

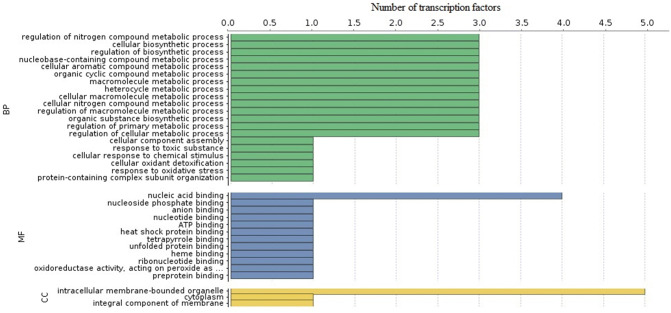

In-silico prediction of gene function and annotation

A gene ontology (GO) term has been categorized into three-cellular components, molecular functions and biological processes. On the basis of similarities, a total of 35 GO terms were assigned. Out of these, 20 were for biological processes, 12 for molecular function and 3 were assigned to cellular component category (Figs. 3 and 4) (Supplementary Table: S1).

Fig. 3.

Gene ontology (GO) classification. Green, blue and yellow bars represent the number of TFs involved in the biological, molecular and cellular processes

Fig. 4.

Functional annotation; pie chart created using Blast2GO. Depicted different GO terms represented as: a biological process, b molecular function, and c cellular component, respectively

Discussion

Abiotic stress, especially the drought stress is one of the major constraints in wheat production globally. Strategies involving breeding of drought-tolerant wheat genotypes is the prime focus of wheat breeders to counter the effect of drought stress and maintain sustainable production. In this context, it becomes pertinent to investigate different factors responsible for drought tolerance (Nezhadahmadi et al. 2013). In the present study, we explored the morphological, biochemical and molecular responses of wheat to applied drought stress. A total of 72 genotypes were screened under irrigated and rainout shelter conditions. Four genotypes which showed improved response to various biochemical and molecular analysis were finally selected for further analysis.

Percent reduction in mean agronomic performance of genotypes over the years revealed that productive tillers had the greatest impact on drought tolerance, which resulted into reduction of biomass and therefore grain yield. Agronomic components are the important features to understand the variations in GY linked with genetic improvement, crop management or environmental factors in cereals (Giunta et al. 1993; del Pozo et al. 2012, 2014, 2016).

Morphology and cellular chemistry of wheat are affected by drought stress

Drought stress caused inhibitory effect on growth of the seedlings with wilting of shoot as compared to the control plants. Maximum effect was observed on IC138852 followed by IC335732. In contrast, IC128335 and IC36761A were least affected by the stress as compared to the control. The maximum increase in MDA level (an indicator of cellular membrane damage) due to the drought stress was observed in IC138852 (1.6-fold) (Fig. 1a). On the other hand, low level of MDA was observed in the drought-tolerant accessions, lowest one was observed in IC36761A (1.25-fold). (Simova-Stoilova et al. 2010) had also reported the deterioration of membrane lipids and integrity of cell membrane due to oxidative damage caused by prolonged drought conditions in sensitive varieties of wheat plants. This data suggests that under the stress conditions, a set of defensive gene/pathway gets activated which maintain lower level of ROS, resulting in decreased MDA, LP and improved stress tolerance. ROS is closely related with abiotic stress which cause membrane damage and electrolyte leakage (Kumar et al. 2013). Accumulation of phytophenolics has been reported to play a defensive role in abiotic stress. We observed a significant increase in TPC in drought-tolerant accessions, while it decreased in the drought-susceptible accessions (Fig. 1c). The highest antioxidant activity and TPC in genotype IC128335 could protect it from the free-radical damage. Contrary to this, reduction in TPC in drought-susceptible genotypes under the stress might be one of the factors responsible for their sensitivity to the stress. A strong correlation between antioxidant activity and accumulation of TPC was reported in wheat and rice by (Kumar et al. 2017) and (Samota et al. 2017).These four contrasting genotypes were used to further study molecular responses under drought stress.

Defensive mechanisms protect plant cells from drought stress

Proline also plays a major role in drought stress and protects the cell membrane from oxidative burst by scavenging reactive oxygen species (Delauney and Verma 1993; Hare et al. 1998). Proline is not only an excellent osmolyte but also acts as a metal-chelator, antioxidative defense molecule, and signaling molecule. It helps to maintain osmotic balance, membrane integrity and concentrations of ROS to prevent oxidative burst in the plant under abiotic stress (Kumar et al. 2017). In the present work, proline levels increased by approximately (2.4-fold) in the genotype (IC128335), but showed the decline in the genotype (IC335732).

To neutralize the oxidative stress, enzymatic defense is usually considered as the most effective mechanism displayed by the plants which can be either enzymatic or non-enzymatic (Farooq et al. 2008). The SOD, CAT and Peroxidase remain the key enzymes, which detoxify the ROS at the time of drought stress (Mittler 2002). The occurrence of antioxidant enzymes in almost every part of the plant cell suggests their significance of ROS detoxification and to guard the cells during various abiotic and biotic stresses. SOD is the main enzyme having role in ROS detoxification of superoxide anion that leads to the formation of H2O2. H2O2 is further detoxified by CAT and POX, peroxidase further reduces H2O2 accumulation and henceforth eliminating MDA (malondialdehyde) to protect the cell from lipid peroxidation and to maintain integrity of cell membrane (Eshdat et al. 1997). Sharma and Shanker Dubey (2005) reported the significant increase in the activity of Glutathione reductase in drought-imposed O. sativa seedlings. The ROS-scavenging enzymes are the major players during ROS scavenging of oxide radicals produced during the time of stress plant have evolved to cope with the adverse conditions. SOD enzymes have the instant expression in the scavenging process (converts O2⋅ to H2O2), the observed increase in SOD activity justify the drought-tolerant behavior of IC128335 (Fig. 1g).

Differential expression of drought-associated transcription factors

TFs have been revealed to play a major role in drought stress by controlling the expression pattern of a genes. The expression of TFs increases gradually at the time of drought stress. In this study we explored the expression analysis of different TFs in response to drought stress like qTaDREB, qTaEXPB23, qTaHSP20, qTaWRKY2, qTaNAC2a, qTaMYB33, qTaHSP-sti, qTaHSP90, qTaHSP40 and qTaAPEX, (Table 4).

WRKY TFs are known to be an important family of transcription factors and have a crucial role, especially during plant growth regulation and development under normal as well stress conditions (Eulgem et al. 2000; Wu et al. 2005; Rushton et al. 2010; Agarwal et al. 2011; Lindemose et al. 2013; Zhu et al. 2013; Bakshi and Oelmüller 2014). Displays its role in stress tolerance i.e. drought, heat, salinity, cold, sugar starvation, phosphate deprivation, H2O2, ozone oxidative stress and UV radiation (Lata et al. 2015). Transcription factors (TFs) such as MYB, bZIP, C2H2,and NAC were expressed to a greater degree in plants under drought (Pereira et al. 2011).

MYB genes have very diverse role in stress response conditions, several MYB TFs have been identified in wheat, and their role have been validated in response to abiotic stresses, Arabidopsis plants overexpressing TaMYB2A, TaMYB19, TaMYB30-B, or TaMYB33 showed improved tolerance to multiple abiotic stresses compared with the wild-type (WT) plants (Qin et al. 2012). Many MYBs have been identified to play a crucial role in mediating the drought and salt tolerance in rice plants and in case of wheat 84 MYB genes have been identified, and only a few have been functionally analyzed, such as, TaMYB1 (Lee et al. 2007), TaMYB2A (Mao et al. 2011), TaMYB19-B (Zhang et al. 2014), TaMYB30-B (Greco et al. 2012), TaMYB33 (Qin et al. 2012), TaMYB74 (Bi et al. 2016) and TaMYB80 (Zhao et al. 2017). The overexpression of TaEXPB23, a wheat β-expansin gene in transgenic tobacco increases the drought tolerance and changed the phenotype (Han et al. 2015). TaEXPB23 is a wheat expansin gene they are the key regulators of plant cell wall extension and their role has been also exploited in abiotic stresses and phytohormone signaling pathways. Constitutive root-specific of TaEXPB23 overexpression enhance drought tolerance in transgenic tobacco lines (Han et al. 2015). Plant perceive signals at the time of stress and that signals is been executed by different stress response elements which finally leads to the accumulation of defense related genes and drought stress is the complex process have role of multiple genes, TFs and enzymes and here we studied the possible role of TaMYB33 genes, which were upregulated. The expression level in tolerant wheat genotypes was high (IC36761A) (1.39 threshold), while the expression was low in susceptible genotype (IC335732) while TaNAC2, a NAC-type wheat transcription factor have displayed the role with enhanced multiple abiotic stress tolerances in Arabidopsis (Mao et al. 2012). Expression of TaNAC2a and TaNAC4a were higher in leaves compared to other plant tissues, and this could be there effective role in drought stress alleviation and SNAC1 have same role as that of NAC TFs and their expression was localized in guard cells during drought stress (Hu et al. 2006; Tang et al. 2012). Triticum aestivum NAC2 gene expression analysis indicates its role in salt, cold, and ABA treatment. Arabidopsis plants expressing TaNAC2 resulted in enhanced tolerance and mitigating drought, salt, and freezing stresses, which further enhanced the expression of abiotic stress-related genes and several physiological indices (Mao et al. 2012). Heat-shock protein 90 (HSP90) is an important class of transcription factor and molecular chaperone protein which is known to have a significant role in tolerance towards abiotic and biotic stresses. One of the best-characterized responses is induction of HSP expression under high temperature. It has been known that HSP90 chaperones are constitutively expressed in most of the organisms under control conditions, while their expression was found to be increased significantly under stress as it is primarily involved in protein folding, activation and signal transduction. HSP90s play a vital role in plant development, stress response and disease resistance (Takahashi et al. 2003; Sangster et al. 2005; Jarosz and Lindquist 2010; Xu et al. 2012; Vishwakarma et al. 2018).

In many cropping regions, drought and heat waves commonly occur simultaneously at reproductive stage in many wheat-growing regions causing total crop yield to decrease by 40% and 60%, respectively, (Prasad et al. 2011; Almer et al. 2012; Mahrookashani et al. 2017). To reduce yield losses, the identification and incorporation of favorable alleles controlling grain yield and its components into cultivated varieties is crucial (Furbank and Tester 2011).

In this study, we observed a positive correlation between two TFs DREB3 and HSP90 in combating drought and heat stress in wheat. A complete CDS mRNA sequence of DREB transcription factor 3 (DREB3) located at chr1DL having EGF like domain (epidermis growth factor), and HSP90 super family TFs located at chrBS having HATPase_C and HKATPase_4 domain were used in this study. We observed downregulation of the TaDREB and TaHSP90 TFs in shoot tissues of drought-susceptible genotypes, whereas, their expression was upregulated in the two drought-tolerant genotypes. Previously, (Agarwal et al. 2016) had also observed upregulation of DREB gene (Ca_02170) and HSP90 genes in the leaf tissues of the tolerant chickpea genotype.

Conclusion

Our study highlighted the role of biochemical and physiological parameters in the identification of drought-tolerant wheat genotypes and provided the insights in the possible involvement of TPC, LP and AO activity as biochemical markers for drought tolerance in wheat plants. The drought-responsive transcription factors were upregulated under conditions of drought stress in the contrasting wheat genotypes. This indicates that transcription factors may play an important role in mitigating abiotic stress in plants and to may help us to develop drought-tolerant varieties of wheat plants. Further, this work has improved our understanding about the structural, functional, and regulatory control of transcription factors which may help in deciphering the complexity of drought tolerance in wheat genotypes.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge Director, ICAR-National Bureau of Plant Genetic Resources (ICAR-NBPGR) New Delhi, for the facilities and support provided to carry out the research work. Sincerely acknowledge the ICAR-Indian Institute of Wheat and Barley Research (ICAR-IIWBR) Karnal-Haryana, for providing wheat germplasm, and Dr. J.C.P for providing Laboratory space to carryout gene expression analysis, NIPB-New Delhi.

Author contributions

SK, DU and NC conceived and designed the research. DU has performed all the experiments and wrote the manuscript. SK, SS, DU, AKS, RB and JK contributed in data analysis. NB and DU has contributed in bioinformatics analysis. JCP contributed in gene expression analysis. SK, JCP, SS, NB and JK contributed in manuscript proofreading. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

References

- AbdElgawad H, Zinta G, Beemster GTS, et al. Future climate CO2 levels mitigate stress impact on plants: increased defense or decreased challenge? Front Plant Sci. 2016;7:556. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.00556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal G, Garg V, Kudapa H, et al. Genome-wide dissection of AP2/ERF and HSP90 gene families in five legumes and expression profiles in chickpea and pigeonpea. Plant Biotechnol J. 2016;14:1563–1577. doi: 10.1111/pbi.12520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal P, Reddy MP, Chikara J. WRKY: its structure, evolutionary relationship, DNA-binding selectivity, role in stress tolerance and development of plants. Mol Biol Rep. 2011;38:3883–3896. doi: 10.1007/s11033-010-0504-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almer C, Laurent-Lucchetti J, Oechslin M, et al. Wheat yield loss attributable to heat waves, drought and water excess at the global, national and subnational scales Wheat yield loss attributable to heat waves, drought and water excess at the global, national and subnational scales. Nat Commun. 2012;3:1293. doi: 10.1016/j.jeem.2017.06.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Appels R, Eversole K, Feuillet C, et al. Shifting the limits in wheat research and breeding using a fully annotated reference genome. Science. 2018;361(6403):eaar7191. doi: 10.1126/science.aar7191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnon DI. Copper enzymes in isolated chloroplasts polyphenoloxidase in Beta vulgaris. Plant Physiol. 1949;24:1–15. doi: 10.1104/pp.24.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arumuganathan K, Earle ED. Estimation of nuclear DNA content of plants by flow cytometry. Plant Mol Biol Rep. 1991;9:229–241. doi: 10.1007/BF02672073. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bakshi M, Oelmüller R. WRKY transcription factors. Plant Signal Behav. 2014;9:e27700. doi: 10.4161/psb.27700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates LS, Waldren RP, Teare ID. Rapid determination of free proline for water-stress studies. Plant Soil. 1973;39:205–207. doi: 10.1007/BF00018060. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett MD, Smith JB. Nuclear DNA amounts in angiosperms. Philos Trans Biol Sci. 1976;334:309–345. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1976.0044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bi H, Luang S, Li Y, et al. Identification and characterization of wheat drought-responsive MYB transcription factors involved in the regulation of cuticle biosynthesis. J Exp Bot. 2016;67:5363–5380. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erw298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohnert HJ. Abiotic stress. Chichester: Wiley; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Cakmak I, Horst WJ. Effect of aluminium on lipid peroxidation, superoxide dismutase, catalase, and peroxidase activities in root tips of soybean (Glycine max) Physiol Plant. 1991;83:463–468. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3054.1991.tb00121.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell BM, Vermeulen SJ, Aggarwal PK, et al. Reducing risks to food security from climate change. Global Food Secur. 2016;11:34–43. doi: 10.1016/j.gfs.2016.06.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Daryanto S, Wang L, Jacinthe P-A. Global Synthesis of drought effects on maize and wheat production. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0156362. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0156362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- del Pozo A, Castillo D, Inostroza L, et al. Physiological and yield responses of recombinant chromosome substitution lines of barley to terminal drought in a Mediterranean-type environment. Ann Appl Biol. 2012;160:157–167. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-7348.2011.00528.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- del Pozo A, Matus I, Serret MD, Araus JL. Agronomic and physiological traits associated with breeding advances of wheat under high-productive Mediterranean conditions. The case of Chile. Environ Exp Bot. 2014;103:180–189. doi: 10.1016/J.ENVEXPBOT.2013.09.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- del Pozo A, Yáñez A, Matus IA, et al. Physiological traits associated with wheat yield potential and performance under water-stress in a Mediterranean environment. Front Plant Sci. 2016;7:987. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.00987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delauney AJ, Verma DPS. Proline biosynthesis and osmoregulation in plants. Plant J. 1993;4:215–223. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313X.1993.04020215.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Devi R, Kaur N, Gupta AK. Potential of antioxidant enzymes in depicting drought tolerance of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) Ind J Biochem Biophys. 2012;49:257–265. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eshdat Y, Holland D, Faltin Z, Ben-Hayyim G. Plant glutathione peroxidases. Physiol Plant. 1997;100:234–240. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3054.1997.tb04779.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eulgem T, Rushton PJ, Robatzek S, Somssich IE. The WRKY superfamily of plant transcription factors. Trends Plant Sci. 2000;5:199–206. doi: 10.1016/S1360-1385(00)01600-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farooq M, Aziz T, Basra SMA, et al. Chilling tolerance in hybrid maize induced by seed priming with salicylic acid. J Agron Crop Sci. 2008;194:161–168. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-037X.2008.00300.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Farooq M, Wahid A, Kobayashi N, et al. Sustainable agriculture. Netherlands, Dordrecht: Springer; 2009. Plant drought stress: effects, mechanisms and management; pp. 153–188. [Google Scholar]

- Fleury D, Luo M-C, Dvorak J, et al. Physical mapping of a large plant genome using global high-information-content-fingerprinting: the distal region of the wheat ancestor Aegilops tauschii chromosome 3DS. BMC Genomics. 2010;11:382. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-11-382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foyer CH, Noctor G. Redox sensing and signalling associated with reactive oxygen in chloroplasts, peroxisomes and mitochondria. Physiol Plant. 2003;119:355–364. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3054.2003.00223.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Furbank RT, Tester M. Phenomics: technologies to relieve the phenotyping bottleneck. Trends Plant Sci. 2011;16:635–644. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2011.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gharsallah C, Fakhfakh H, Grubb D, Gorsane F. Effect of salt stress on ion concentration, proline content, antioxidant enzyme activities and gene expression in tomato cultivars. AoB Plants. 2016;8:plw055. doi: 10.1093/aobpla/plw055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giunta F, Motzo R, Deidda M. Effect of drought on yield and yield components of durum wheat and triticale in a Mediterranean environment. F Crop Res. 1993;33:399–409. doi: 10.1016/0378-4290(93)90161-F. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Greco M, Chiappetta A, Bruno L, Bitonti MB. In Posidonia oceanica cadmium induces changes in DNA methylation and chromatin patterning. J Exp Bot. 2012;63:695–709. doi: 10.1093/jxb/err313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han Y, Chen Y, Yin S, et al. Over-expression of TaEXPB23, a wheat expansin gene, improves oxidative stress tolerance in transgenic tobacco plants. J Plant Physiol. 2015;173:62–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2014.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hare PD, Cress WA, Van Staden J. Dissecting the roles of osmolyte accumulation during stress. Plant Cell Environ. 1998;21:535–553. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3040.1998.00309.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hassan NM, El-Bastawisy ZM, El-Sayed AK, et al. Roles of dehydrin genes in wheat tolerance to drought stress. J Adv Res. 2015;6:179–188. doi: 10.1016/j.jare.2013.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatano T, Kagawa H, Yasuhara T, Okuda T. Two new flavonoids and other constituents in licorice root: their relative astringency and radical scavenging effects. Chem Pharm Bull (Tokyo) 1988;36:2090–2097. doi: 10.1248/cpb.36.2090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiscox JD, Israelstam GF. A method for the extraction of chlorophyll from leaf tissue without maceration. Can J Bot. 1979;57:1332–1334. doi: 10.1139/b79-163. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hu H, Dai M, Yao J, et al. Overexpressing a NAM, ATAF, and CUC (NAC) transcription factor enhances drought resistance and salt tolerance in rice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:12987–12992. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604882103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarosz DF, Lindquist S. Hsp90 and environmental stress transform the adaptive value of natural genetic variation. Science (80-) 2010;330:1820–1824. doi: 10.1126/science.1195487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y, Zeng B, Zhao H, et al. Genome-wide transcription factor gene prediction and their expressional tissue-specificities in maizeF. J Integr Plant Biol. 2012;54:616–630. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-7909.2012.01149.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang Y, Khan S, Ma X. Climate change impacts on crop yield, crop water productivity and food security: a review. Prog Nat Sci. 2009;19:1665–1674. doi: 10.1016/j.pnsc.2009.08.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar MN, Jane WN, Verslues PE. Role of the putative osmosensor Arabidopsis histidine kinase1 in dehydration avoidance and low-water-potential response. Plant Physiol. 2013;161(2):942–953. doi: 10.1104/pp.112.209791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S, Beena AS, Awana M, Singh A. Physiological, biochemical, epigenetic and molecular analyses of wheat (Triticum aestivum) genotypes with contrasting salt tolerance. Front Plant Sci. 2017;8:1151. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.01151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larcher W. Ecophysiology and stress physiology of functional groups. Heidelberg: Springer, Berlin; 2003. Physiological plant ecology. [Google Scholar]

- Lata C, Muthamilarasan M, Prasad M. Elucidation of abiotic stress signaling in plants. New York: Springer New York; 2015. Drought stress responses and signal transduction in plants; pp. 195–225. [Google Scholar]

- Lee TG, Jang CS, Kim JY, et al. A Myb transcription factor (TaMyb1) from wheat roots is expressed during hypoxia: roles in response to the oxygen concentration in root environment and abiotic stresses. Physiol Plant. 2007;129:375–385. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3054.2006.00828.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lesk C, Rowhani P, Ramankutty N. Influence of extreme weather disasters on global crop production. Nature. 2016;529:84–87. doi: 10.1038/nature16467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li F, Zhang L, Ji H, et al. The specific W-boxes of GAPC5 promoter bound by TaWRKY are involved in drought stress response in wheat. Plant Sci. 2020;26:110460. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2020.110460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindemose S, O’Shea C, Jensen M, et al. Structure, function and networks of transcription factors involved in abiotic stress responses. Int J Mol Sci. 2013;14:5842–5878. doi: 10.3390/ijms14035842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipiec J, Doussan C, Nosalewicz A, Kondracka K. Effect of drought and heat stresses on plant growth and yield: a review. Int Agrophys. 2013;27:463–477. doi: 10.2478/intag-2013-0017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Madani A, Rad AS, Pazoki A, et al. Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) grain filling and dry matter partitioning responses to source: sink modifications under postanthesis water and nitrogen deficiency. Acta Sci Agron. 2010;32:145–151. doi: 10.4025/actasciagron.v32i1.6273. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mahrookashani A, Siebert S, Hüging H, Ewert F. Independent and combined effects of high temperature and drought stress around anthesis on wheat. J Agron Crop Sci. 2017;203:453–463. doi: 10.1111/jac.12218. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mao X, Jia D, Li A, et al. Transgenic expression of TaMYB2A confers enhanced tolerance to multiple abiotic stresses in Arabidopsis. Funct Integr Genomics. 2011;11:445–465. doi: 10.1007/s10142-011-0218-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao X, Zhang H, Qian X, et al. TaNAC2, a NAC-type wheat transcription factor conferring enhanced multiple abiotic stress tolerances in Arabidopsis. J Exp Bot. 2012;63:2933–2946. doi: 10.1093/jxb/err462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matiu M, Ankerst DP, Menzel A. Interactions between temperature and drought in global and regional crop yield variability during 1961–2014. PLoS ONE. 2017;12:e0178339. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0178339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittler R. Oxidative stress, antioxidants and stress tolerance. Trends Plant Sci. 2002;7:405–410. doi: 10.1016/S1360-1385(02)02312-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nezhadahmadi A, Prodhan ZH, Faruq G. Drought tolerance in wheat. Sci World J. 2013;2013:12. doi: 10.1155/2013/610721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira S, Guimarães F, Carvalho J, et al. Transcription factors expressed in soybean roots under drought stress. Genet Mol Res. 2011;10:3689–3701. doi: 10.4238/2011.October.21.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pradhan GP, Prasad PVV, Fritz AK, et al. Effects of drought and high temperature stress on synthetic hexaploid wheat. Funct Plant Biol. 2012;39:190. doi: 10.1071/FP11245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prasad PVV, Pisipati SR, Momčilović I, Ristic Z. Independent and combined effects of high temperature and drought stress during grain filling on plant yield and chloroplast EF–Tu expression in spring wheat. J Agron Crop Sci. 2011;197:430–441. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-037X.2011.00477.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Qin Y, Wang M, Tian Y, et al. Over-expression of TaMYB33 encoding a novel wheat MYB transcription factor increases salt and drought tolerance in Arabidopsis. Mol Biol Rep. 2012;39:7183–7192. doi: 10.1007/s11033-012-1550-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravikumar G, Manimaran P, Voleti SR, et al. Stress-inducible expression of AtDREB1A transcription factor greatly improves drought stress tolerance in transgenic indica rice. Transgenic Res. 2014;23:421–439. doi: 10.1007/s11248-013-9776-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reczek CR, Chandel NS. ROS-dependent signal transduction. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2015;33:8–13. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2014.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rushton PJ, Somssich IE, Ringler P, Shen QJ. WRKY transcription factors. Trends Plant Sci. 2010;15:247–258. doi: 10.1016/J.TPLANTS.2010.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sairam RK, Tyagi A. Physiology and molecular biology of salinity stress tolerance in plants. Curr Sci. 2004;10:407–21. [Google Scholar]

- Samota MK, Sasi M, Awana M, et al. Elicitor-induced biochemical and molecular manifestations to improve drought tolerance in rice (Oryza sativa L.) through seed-priming. Front Plant Sci. 2017;8:934. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.00934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sangster TA, Queitsch C, Dolan L, Freeling M. The HSP90 chaperone complex, an emerging force in plant development and phenotypic plasticity. This review comes from a themed issue on growth and development edited. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2005;8:86–92. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2004.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma P, Shanker Dubey R. Modulation of nitrate reductase activity in rice seedlings under aluminium toxicity and water stress: role of osmolytes as enzyme protectant. J Plant Physiol. 2005;162:854–864. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2004.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simova-Stoilova L, Vaseva I, Grigorova B, et al. Proteolytic activity and cysteine protease expression in wheat leaves under severe soil drought and recovery. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2010;48:200–206. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2009.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh D, Laxmi A. Transcriptional regulation of drought response: a tortuous network of transcriptional factors. Front Plant Sci. 2015 doi: 10.3389/fpls.2015.00895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singleton VL, Orthofer R, Lamuela-Raventós RM. [14] Analysis of total phenols and other oxidation substrates and antioxidants by means of folin-ciocalteu reagent. Methods Enzymol. 1999;299:152–178. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(99)99017-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi A, Casais C, Ichimura K, Shirasu K. HSP90 interacts with RAR1 and SGT1 and is essential for RPS2-mediated disease resistance in Arabidopsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:11777–11782. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2033934100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang Y, Liu M, Gao S, et al. Molecular characterization of novel TaNAC genes in wheat and overexpression of TaNAC2a confers drought tolerance in tobacco. Physiol Plant. 2012;144:210–224. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3054.2011.01539.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tripathi P, Rabara RC, Rushton PJ. A systems biology perspective on the role of WRKY transcription factors in drought responses in plants. Planta. 2014;239:255–266. doi: 10.1007/s00425-013-1985-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valifard M, Mohsenzadeh S, Kholdebarin B, Rowshan V. Effects of salt stress on volatile compounds, total phenolic content and antioxidant activities of Salvia mirzayanii. South Afr J Bot. 2014;93:92–97. doi: 10.1016/J.SAJB.2014.04.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vishwakarma H, Junaid A, Manjhi J, et al. Heat stress transcripts, differential expression, and profiling of heat stress tolerant gene TaHsp90 in Indian wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) cv C306. PLoS ONE. 2018 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0198293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei TM, Chang XP, Min DH, Jing RL. Analysis of genetic diversity and trapping elite alleles for plant height in drought-tolerant wheat cultivars. Acta Agron Sin. 2010;36:895–904. doi: 10.1016/S1875-2780(09)60053-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wu K-L, Guo Z-J, Wang H-H, Li J. The WRKY family of transcription factors in rice and Arabidopsis and their origins. DNA Res. 2005;12:9–26. doi: 10.1093/dnares/12.1.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia N, Zhang G, Sun Y-F, et al. TaNAC8, a novel NAC transcription factor gene in wheat, responds to stripe rust pathogen infection and abiotic stresses. Physiol Mol Plant Pathol. 2010;74:394–402. doi: 10.1016/J.PMPP.2010.06.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xu ZS, Li ZY, Chen Y, et al. Heat shock protein 90 in plants: molecular mechanisms and roles in stress responses. Int J Mol Sci. 2012;13:15706–15723. doi: 10.3390/ijms131215706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Liu G, Zhao G, et al. Characterization of a wheat R2R3-MYB transcription factor gene, TaMYB19, involved in enhanced abiotic stresses in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Physiol. 2014;55:1802–1812. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcu109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y, Tian X, Wang F, et al. Characterization of wheat MYB genes responsive to high temperatures. BMC Plant Biol. 2017 doi: 10.1186/s12870-017-1158-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu X, Liu S, Meng C, et al. WRKY transcription factors in wheat and their induction by biotic and abiotic stress. Plant Mol Biol Rep. 2013;31:1053–1067. doi: 10.1007/s11105-013-0565-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.