Abstract

Spain has been one of the most affected countries by the COVID-19 outbreak. As of April 28, 2020, the number of confirmed cases is 210 773, including 102 548 patients recovered, more than 10 300 admitted to the ICU, and 23 822 deaths, with a global case fatality rate of 11.3%. From the perspective of donation and transplantation, the Spanish system first focused on safety issues, providing recommendations for donor evaluation and testing, and to rule out SARS-CoV-2 infection in potential recipients prior to transplantation. Since the country entered into an epidemiological scenario of sustained community transmission and saturation of intensive care, developing donation and transplantation procedures has become highly complex. Since the national state of alarm was declared in Spain on March 13, 2020, the mean number of donors has declined from 7.2 to 1.2 per day, and the mean number of transplants from 16.1 to 2.1 per day. Increased mortality on the waiting list may become a collateral damage of this terrible pandemic.

KEYWORDS: clinical research/practice, donors and donation, donors and donation: donor evaluation, donors and donation: donor-derived infections, health services and outcomes research, infection and infectious agents – viral, infectious disease, organ procurement and allocation, organ transplantation in general

Abbreviations: COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; GESITRA-IC, Group for the Study of Infection in Transplantation and the Immunocompromised Host (Grupo de Estudio de Infección en el Transplante y el Huésped Inmunocomprometido; ICU, intensive care unit; ONT, Organización Nacional de Trasplantes; RT-PCR, reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction; SARS-CoV-2, Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus type 2; SEMICYUC, Spanish Society of Intensive and Critical Care, and Coronary Units (Sociedad Española de Medicina Intensiva, Crítica y Unidades Coronarias)

1. INTRODUCTION

At the beginning of December 2019, clusters of patients diagnosed of pneumonia of unknown origin were reported in the city of Wuhan, province of Hubei (China).1 The pathogen was identified as a new betacoronavirus, named severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus type 2 (SARS-CoV-2), with a high phylogenetic similarity with the SARS-CoV virus, first identified in the Chinese province of Guangdong in 2002.2 By international consensus, the infection caused by SARS-CoV-2 is named Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). In the last weeks, the number of cases of COVID-19 has increased to more than 3 million reported by 185 countries throughout the world.3 On March 11, 2020, the World Health Organization officially declared the COVID-19 outbreak a pandemic.4

Spain has been one of the most affected countries in the world in terms of absolute number of diagnosed cases. On March 13, 2020 (legally effective on March 15), the Government declared a national state of alarm, with regulations targeted to facilitate diagnosis, ensure appropriate treatment of cases, and reduce the spread of COVID-19, including measures of national lockdown, confinement of the population, and restricted mobility.5 As of April 28, 2020, the number of confirmed cases in Spain is 210,773, including 105 548 patients recovered, more than 10 300 admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU), and 23 822 deaths, with a global case fatality rate of 11.3%.6 The accumulated incidence of COVID-19 in the last 14 days is 81.28 per 100 000 inhabitants, with marked variations across regions (from 10.63 to 182.78). The country as a whole is currently considered to be in epidemiological scenarios 3 (sustained community transmission) and 4 (intensive care capacity saturated and health-care system overwhelmed), as described by the European Centre for Disease Control and Prevention.7

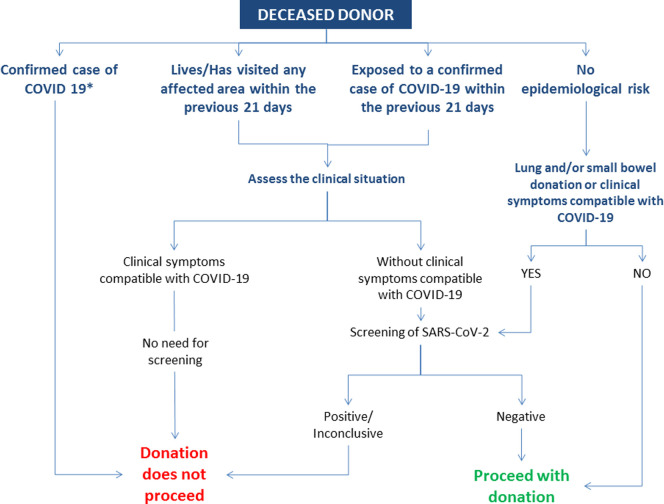

From the perspective of donation and transplantation, the Spanish system first focused on the possibility of donor-derived COVID-19. In January 2020, the Organización Nacional de Trasplantes (ONT) and the Group for the Study of Infection in Transplantation and the Immunocompromised Host (GESITRA-IC) of the Spanish Society of Infectious Diseases and Clinical Microbiology (SEIMC) started to issue recommendations for donor evaluation and testing. Current recommendations applicable to deceased organ donors are represented in Figure 1.8 In summary, donation does not proceed in confirmed cases of COVID-19. In the event of potential donors with epidemiological risk (defined as exposure to a confirmed case of COVID-19 and/or having visited any affected area during the previous 21 days) and a clinical picture compatible with COVID-19, donation does not proceed even with no screening or a negative result. In asymptomatic potential donors with epidemiological risk, donor screening for SARS-CoV-2 by reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) is performed. Donation does not proceed if the result is positive or inconclusive. Testing is also extended to all potential donors with no epidemiological risk if donation of lung and/or small bowel is considered, or if they present symptoms compatible with COVID-19. Since the entire country currently represents an affected area, universal screening is now the rule as derived from applying the above described recommendations. Also, bearing in mind the number of cured patients in the country, organ donation is considered after a minimum period of 21 days following the resolution of symptoms and the completion of treatment, provided that viral clearance has been demonstrated and a cautious case by case risk/benefit assessment has been performed. In live donation, the recommendation is to defer surgery for 21 days in donors with epidemiological risk. Currently, all live donation procedures are being postponed. The matching runs of the national kidney paired exchange program have been deferred as well.

FIGURE 1.

Summary of Spanish recommendations for the evaluation and testing of deceased organ donors with regards to SARS-CoV-2. *Donation will be considered on a case-by-case basis in cured cases of COVID-19 after a minimum of 21 d following resolution of symptoms and completion of therapy. A cured case is defined as follows: Patient with confirmed COVID-19 (or highly suspicious) who was hospitalized: 21 d after the complete resolution of symptoms AND two negative SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR in respiratory tract samples obtained >24 h apart. Patient with confirmed COVID-19 who was isolated at home: 21 d after the complete resolution of symptoms AND 2 negative SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR in respiratory tract samples obtained >24 h apart. Patient with probable COVID-19 (ie, with no microbiological confirmation), who was isolated at home with suggestive symptoms and/or exposure to a confirmed case of COVID-19: if symptoms continue, donation will not proceed; if contact has occurred within the previous 21 d, screening for SARS-CoV-2 will be performed; if contact has occurred beyond the previous 21 d, donation will be considered as for any other potential donor [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

With regard to the samples for testing, our recommendation is to use samples from the upper (nasopharyngeal and oropharyngeal swab) or the lower respiratory tract (preferentially, bronchoalveolar lavage) taken within 24 hours prior to organ recovery. A brochoalveolar lavage sample is always preferred, and required in case of lung or small bowel donation. The deferral period set of 21 days differs from that recommended by others.7 Although the incubation period of COVID-19 has been consistently established within the range of 2-14 days, we wanted to rule out potential outliers.

In practice, applying the previously mentioned scheme has proved challenging due to the limited access to RT-PCR testing in some hospitals and the time required to have results available. Laboratories have become progressively overloaded by the number of samples to be tested, and their restricted capacity to provide results smoothly. This has slowed down deceased donation processes to an extent that some have been cancelled—understandably—upon request of donor families or by decision of the donor center. Since March 13, 2020 (national state of alarm) until April 23, 2020, only 1 out of 58 (2%) potential donors reported to ONT have tested positive for SARS-CoV-2. Donation did not proceed in this case, nor in 7 additional cases—in 5 of them due to logistical issues related to the COVID-19 outbreak in donor and/or recipient hospitals. In total, 88 transplants have been performed during this same period of time. As of today, no suspected cases of donor-derived COVID-19 have been reported to ONT.

As Spain was entering in scenarios 3-4, the need to test patients on the waiting list for organ transplantation became a pressing issue. There is paucity of information regarding the evolution of COVID-19 in solid organ transplant recipients. However, based on the outcome of the infection caused by endemic human coronavirus in immunosuppressed patients,9 we can expect an increased rate of complications in this patient population.10 This is supported by the scarce available evidence with similar coronaviruses, as SARS-CoV or the Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV).11 , 12 In accordance with this hypothesis, a recently published experience from a transplant center at Madrid (Spain) including 18 recipients of solid organs with COVID-19 reported a case fatality rate of 27.8%, with 30.8% of survivors developing progressive respiratory failure and acute respiratory distress syndrome.13 It is also likely that the period of viral clearing is longer than in nontransplanted patients, with the corresponding impact on the control of disease transmission.14 , 15 Proceeding with a transplant in a patient who may be infected can, not only place that patient at high risk following immunosuppression, but turn them into “super-shedders” of the virus particularly among health-care workers.10 This has prompted us to issue the recommendation of testing recipients upon their arrival to the hospital prior to transplantation—which will not proceed should the patient exhibit symptoms compatible with COVID-19 or test positive for SARS-CoV-2.

Safety issues have however not been the most important barrier in our field, but the saturation of the health-care system and of the ICU capacity, that has prompted the Spanish Society of Intensive and Critical Care, and Coronary Units (SEMICYUC) to develop a national contingency plan.16 As the number of cases started raising in Spain, and particularly since the state of alarm was declared, ICU resources have been focused on the treatment of severe cases of COVID-19. Spain has 3,598 ICU beds in public hospitals. In the most affected regions, hospitals have increased their ICU capacity by transforming other hospital areas into ICUs and new hospitals have been set up to care for critically ill patients. Hotels are being medicalized to treat the less critical COVID-19 patients. Still, health-care professionals are making difficult decisions on who will benefit the most of the limited intensive care resources available in the midst of a pandemic that is severely striking the health-care system.17 The situation is even more critical considering the number of health-care workers becoming infected (health-care workers represent 15.5% of the infected population)18 or forced to isolation. In this scenario, sustaining a deceased donation program has become highly complex. Similarly, it is a real challenge to care for transplant patients immediately after surgery in the ICU—or in any hospital area—due to diminished capacity and the risk of nosocomial infection by SARS-CoV-2, with the potential implications referred above. Of note, in an ongoing national data collection, of 363 recipients of solid organs who have developed COVID-19 during the outbreak, 50 (14%) acquired the infection within the hospital—the rest having acquired the infection in the community.

The ONT has instructed centers to set priorities in this epidemiological situation. Centers in less affected areas should try to develop donation and transplantation as close to usual as possible. Centers in the most affected areas may decide to pursue donation only from ideal donors (both donation after brain death and controlled donation after circulatory death), temporarily suspending more complex donation procedures as those represented by intensive care to facilitate organ donation19 and uncontrolled donation after circulatory death.20 Similarly, these centers may limit their activity to providing transplantation to critically ill patients and to those with particular difficulties to access transplantation based on their immunological and/or anthropometrical characteristics (eg, pediatric patients), deferring less urgent procedures, particularly kidney and pancreas transplantation. An additional challenge has been the mobilization of recovery teams, who face restrictions in travelling, particularly to more affected areas. ONT has opted for applying current allocation criteria in a more flexible manner to optimize organ utilization and reduce the need for recovery teams moving across the country. In general terms, organ recovery by local teams has been prioritized.

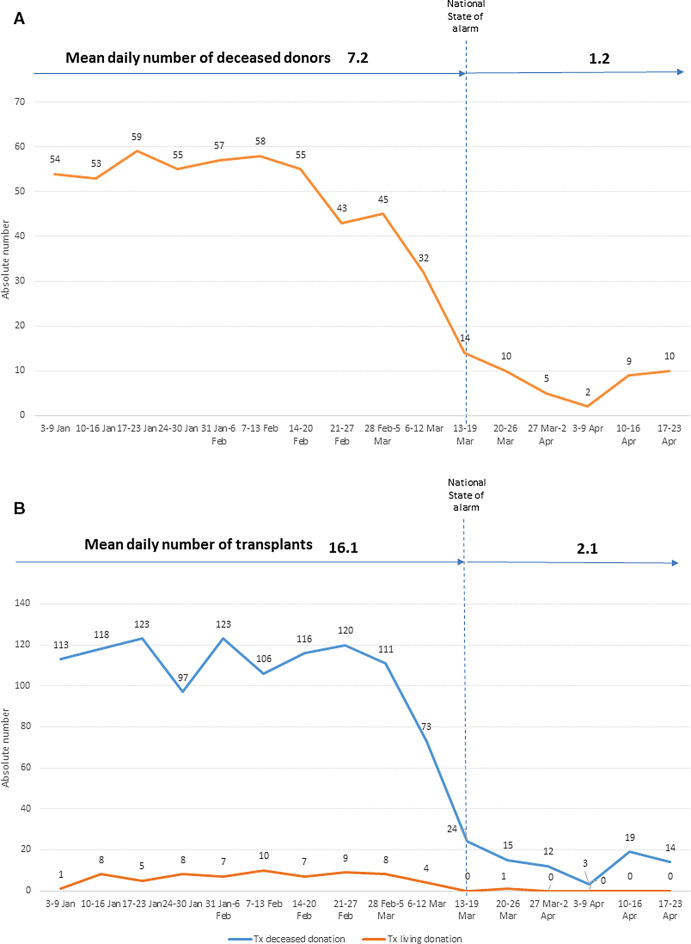

In 2019, Spain reached a historical maximum in organ donation (2302 deceased donors, 49 per million population) and in organ transplantation (5449 transplant procedures, 116 per million population). The evolution of organ donation and transplantation during 2020 in Spain is shown in Figure 2. Between January 1 and March 12, 2020, the mean number of actual deceased organ donors was 7.2 per day and the mean number of organ transplants was 16.1 per day (15.2 transplants from deceased donors per day). During the first 6 weeks after the state of alarm was declared, the figures were 1.2 and 2.1, respectively. In total, 88 transplants have been undertaken (40 kidney, 34 liver, and 14 heart transplant procedures). Table 1 shows the weekly mean of transplant procedures per organ type during the latest period and the corresponding values for the year 2019. Despite differences in the incidence of COVID-19 across regions, the decrease in activity has occurred equally across the entire country. Eight deaths on the waiting list (1.3 per week) have been registered during the outbreak, compared to a previous rate of 1.4 deaths per week. However, it is too early to evaluate the impact of the dramatic decrease in transplant activity upon mortality among listed patients.

FIGURE 2.

Number of actual deceased organ donors (A) and number of transplant procedures from deceased and live organ donors (B) at 7-d intervals. Spain 2020 [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

TABLE 1.

Absolute number and weekly mean of transplant procedures per type of organ during the outbreak of COVID-19 in Spain (since the state of alarm was declared on March 13, 2020 until April 23, 2020), compared with 2019

| Transplants March 13-April 23, 2020 (absolute number) | Transplants March 13-April 23, 2020 (weekly mean) | Transplants 2019 (absolute number) | Transplants 2019 (weekly mean) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kidney | 40 | 6.7 | 3423 | 65.8 |

| Liver | 34 | 5.7 | 1227 | 23.6 |

| Heart | 14 | 2.3 | 300 | 5.8 |

| Lung | 0 | 0 | 419 | 8.1 |

| Pancreas | 0 | 0 | 76 | 1.5 |

| Small bowel | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0.1 |

| Total | 88 | 14.7 | 5449 | 104.8 |

There are different reasons that can explain the decrease in donation and transplantation activities during the outbreak, although some are difficult to prove and measure at the present time. Hospitals have reported a decrease in the number of neurocritical patients admitted to the hospital. In a context of an overwhelmed health-care system and a saturated ICU capacity, admission of neurocritical patients to the ICU has likely decreased and may justify a lower reporting of potential donors to the coordination teams. Potential donor losses have been reported due to positive screening for SARS-CoV-2, as mentioned above. Once activated, logistical problems are frequent, either associated with restricted mobility of recovery teams or prolonged time needed for testing potential donors and recipients. Transplant teams are frequently declining organ offers after a risk assessment considering the clinical situation of potential recipients on the waiting list and limited COVID-19 free areas available in the hospital. Human resources in donor coordination and transplant teams have been reduced due to cases of COVID-19 among professionals or need for isolation. Recipients have also declined transplantation on a number of occasions after informed consent. Given the current situation in the country, it is very likely that donation and transplantation activities will take time to recover. This message has been transparently transmitted to the public—and to desperate patients on the waiting list.

Organ donation and transplantation is a good thermometer of what happens in a hospital. Not by chance, SEMICYUC considers donation as an indicator of quality in intensive care.21 For deceased donation and transplantation to work, a number of other processes must be operational at a normal level in the hospital and in the ICU setting. At a time when the priority is to control COVID-19 in the midst of an overwhelmed health-care system with limited areas in the hospital free of COVID-19, donation and transplantation activities have dramatically and unavoidably decreased. Mortality on the waiting list may become a collateral damage of this terrible pandemic.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Every evening, at 20 hours, Spain breaks out in a big applause from windows and balconies in acknowledgment of health-care professionals who are combating COVID-19 at the frontline in hospitals and other facilities. With these lines, the authors wish to join that unique gesture of recognition that also includes all members of the Spanish donor coordination and transplant teams.

DISCLOSURE

The authors have no conflict of interest to disclose as described by the American Journal of Transplantation.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

REFERENCES

- 1.Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395:497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhu NA, Zhang D, Wang W, et al. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:727–733. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.COVID-19 Dashboard by the Center for Systems Science and Engineering (CSSE) at Johns Hopkins University (JHU). https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html. Accessed April 13, 2020.

- 4.WHO Director-General’s opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19 - 20 March 2020. https://www.who.int/dg/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19---20-march-2020. Accessed April 13, 2020.

- 5.Real Decreto 463/2020, de 14 de marzo, por el que se declara el estado de alarma para la gestión de la situación de crisis sanitaria ocasionada por el COVID-19. https://www.boe.es/buscar/doc.php?id=BOE-A-2020-3692. Accessed April 13, 2020.

- 6.Ministerio de Sanidad, Secretaría General de Sanidad, Dirección General de Salud Pública, Calidad e Innovación, Centro de Coordinación de Alertas y Emergencias Sanitarias. Actualización nº 74 (13 de Abril de 2020). Enfermedad por el coronavirus (COVID-19) (datos consolidados a las 21:00 horas del 12 de Abril de 2020). https://www.mscbs.gob.es/profesionales/saludPublica/ccayes/alertasActual/nCov-China/documentos/Actualizacion_74_COVID-19.pdf.Accessed April 13, 2020.

- 7.Novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic: increased transmission in the EU/EEA and the UK – sixth update. https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/sites/default/files/documents/RRA-sixth-update-Outbreak-of-novel-coronavirus-disease-2019-COVID-19.pdf. Accessed April 13, 2020.

- 8.Summary of Spanish recommendations regarding organ donation and transplantation in relation to the COVID-19 outbreak. http://www.ont.es/infesp/RecomendacionesParaProfesionales/Spanish%20Recommendations%20on%20Organ%20Donation%20and%20Transplantation%20COVID-19%20ONT.pdf. Accessed April 13, 2020.

- 9.Garbino J, Crespo S, Aubert J-D, et al. A prospective hospital-based study of the clinical impact of non-severe acute respiratory syndrome (Non-SARS)-related human coronavirus infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43:1009–1015. doi: 10.1086/507898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Michaels MG, La Hoz RM, Danziger Isakov L, et al. Coronavirus disease 2019: implications of emerging infections for transplantation [published online ahead of print February 24, 2020]. Am J Transplant. 10.1111/ajt.15832 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Kumar D, Tellier R, Draker R, et al. Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) in a liver transplant recipient and guidelines for donor SARS screening. Am J Transplant. 2003;3:977–981. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-6143.2003.00197.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.AlGhamdi M, Mushtaq F, Awn N, Shalhoub S. MERS CoV infection in two renal transplant recipients: case report. Am J Transplant. 2015;15:1101–1104. doi: 10.1111/ajt.13085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fernández-Ruiz M, Andrés A, Loinaz C, et al. COVID-19 in solid organ transplant recipients: a single-center case series from Spain [published online ahead of print April 16, 2020]. Am J Transplant. 10.1111/ajt.15929 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Ogimi C, Greninger AL, Waghmare AA, et al. Prolonged shedding of human coronavirus in hematopoietic cell transplant recipients: risk factors and viral genome evolution. J Infect Dis. 2017;216:203–209. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jix264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim S-H, Ko J-H, Park GE, et al. Atypical presentations of MERS-CoV infection in immunocompromised hosts. J Infect Chemother. 2017;23:769–773. doi: 10.1016/j.jiac.2017.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Plan de contingencia para los servicios de medicina intensiva frente a la pandemia COVID-19. https://semicyuc.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Plan-Contingencia-COVID-19.pdf. Accessed April 13, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Recomendaciones éticas para la toma de decisiones en la situación excepcional de crisis por pandemia COVID-19 en las unidades de cuidados intensivos. https://semicyuc.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/%C3%89tica_SEMICYUC-COVID-19.pdf. Accessed April 13, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Coronavirus: 25.000 sanitarios infectados en España, 5.600 más en 6 días. https://www.redaccionmedica.com/secciones/sanidad-hoy/coronavirus-25-000-sanitarios-infectados-en-espana-5-600-mas-en-6-dias-4086?utm_source=redaccionmedica&utm_medium=email-2020-04-12&utm_campaign=boletin. Accessed April 13, 2020.

- 19.Martín-Delgado MC, Martínez-Soba F, Masnou N, et al. Summary of Spanish recommendations on intensive care to facilitate organ donation. Am J Transplant. 2019;19(6):1782–1791. doi: 10.1111/ajt.15253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Coll E, Miñambres E, Sánchez-Fructuoso A, et al. Uncontrolled donation after circulatory death: a unique opportunity. Transplantation. 2020. 10.1097/TP.0000000000003139. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Indicadores de Calidad en el enfermo crítico. Actualization. 2017. https://semicyuc.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/indicadoresdecalidad2017_semicyuc_spa-1.pdf. Accessed April 13, 2020.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.