Culture-based and culture-independent approaches were utilized to reveal bacterial community changes on chicken carcasses at different processing steps and potential routes from the local processing environment. Current commercial processing effectively reduced bacterial loads on carcasses. Poultry processes have similar processes across facilities, but various processing arrangements and operating parameters could impact the bacterial transmission and persistence on carcasses differently. This study showed the use of a single tunnel incorporating scalding, defeathering and plucking may undesirably distribute the thermoduric bacteria, e.g., Campylobacter and Anoxybacillus, between the local environment and carcasses, whereas this does not occur when these steps are separated. The length of immersion and air chilling also impacted bacterial diversity on carcasses. Air chilling can transfer Pseudomonas from wall surfaces onto carcasses; this may subsequently influence chicken product shelf life. This study helps poultry processors understand the impact of current commercial processing and improve the chicken product quality and safety.

KEYWORDS: poultry processing, environment, shelf life, Campylobacter, Pseudomonas, Anoxybacillus, microbiome, 16S rRNA, bacterial diversity, food safety

ABSTRACT

It is important for the poultry industry to maximize product safety and quality by understanding the connection between bacterial diversity on chicken carcasses throughout poultry processing to the end of shelf life and the impact of the local processing environment. Enumeration of total aerobic bacteria, Campylobacter and Pseudomonas, and 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequencing were used to evaluate the processing line by collecting 10 carcasses from five processing steps: prescald, postplucker, pre- and post-immersion chill, and post-air chill. The diversity throughout a 12-day shelf life was also determined by examining 30 packaged carcasses. To identify the sources of possible contamination, scald water tank, immersion chilling water tank, air samples, and wall surfaces in the air-chill room were analyzed. Despite bacterial reductions on carcasses (>5 log10 CFU/ml) throughout the process, each step altered the bacterial diversity. Campylobacter was a minor but persistent component in the bacterial community on carcasses. The combination of scalding, defeathering, and plucking distributed thermophilic spore-forming Anoxybacillus to carcasses, which remained at a high abundance on carcasses throughout subsequent processes. Pseudomonas was not isolated from carcasses after air chilling but was abundant on the wall of the air-chill room and became the predominant taxon at the end of shelf life, suggesting possible contamination through air movement. The results suggest that attention is needed at each processing step, regardless of bacterial reductions on carcasses. Changing scalding water regularly, maintaining good hygiene practices during processing, and thorough disinfection at the end of each processing day are important to minimize bacterial transmission.

IMPORTANCE Culture-based and culture-independent approaches were utilized to reveal bacterial community changes on chicken carcasses at different processing steps and potential routes from the local processing environment. Current commercial processing effectively reduced bacterial loads on carcasses. Poultry processes have similar processes across facilities, but various processing arrangements and operating parameters could impact the bacterial transmission and persistence on carcasses differently. This study showed the use of a single tunnel incorporating scalding, defeathering and plucking may undesirably distribute the thermoduric bacteria, e.g., Campylobacter and Anoxybacillus, between the local environment and carcasses, whereas this does not occur when these steps are separated. The length of immersion and air chilling also impacted bacterial diversity on carcasses. Air chilling can transfer Pseudomonas from wall surfaces onto carcasses; this may subsequently influence chicken product shelf life. This study helps poultry processors understand the impact of current commercial processing and improve the chicken product quality and safety.

INTRODUCTION

Chicken has been the most consumed meat in Australia since 2004 (1) and has been identified as one of the most important vehicles for Campylobacter transmission (2, 3). Campylobacter is the leading bacterial cause for human foodborne disease globally, including the United States (4), the European Union (5), and Australia (6). A range of other microorganisms also affect the safety and quality of chicken products, such as Salmonella and Pseudomonas, which may come into contact with chicken products during production or are deposited onto chicken products during processing and storage (7–9). Some of these bacteria can subsequently cause food safety and quality concerns throughout the supply chain and for consumers (10). Thus, hygienic practices and controls are critical for successful chicken processing ensuring public health and product quality. Processing steps often incorporate hurdle technology to efficiently eliminate bacterial populations and limit the presence of foodborne pathogens.

In recent years, efforts have been made to study chicken carcass safety and quality by looking at the bacterial diversity, either on chicken carcasses through processing or from the processing environment (8, 9, 11–14). These studies have investigated various steps during poultry processing with corresponding environmental samples and have demonstrated the impact of current processing interventions on the bacterial diversity on carcasses, which cannot be readily realized by culture-based techniques. In particular, two recent studies profiled the bacterial diversity through chicken processing with the assessment of the local processing environment (8, 9). Although there might be differences between the sampling strategies, experimental methodologies, and analytical approaches, both studies indicated the chilling process as a main contamination point after examining the changes of bacterial diversity on carcasses after immersion chilling and in the immersion chilling water. Another similar finding from the two studies was the low relative abundance of Pseudomonas on carcasses after immersion chilling, with the study by Chen et al. (8) suggesting that air chilling may redeposit Pseudomonas onto carcasses. Wang et al. (9) also claimed that scalding may be another important contamination point and could have a selective tendency for heat-resistant mesophilic organisms (15). In addition, Campylobacter was suggested to only take up a small proportion of the bacterial community on carcasses since the results of 16S rRNA gene sequencing indicated that it was at a low or below the limit of detection (8, 14). However, the link between bacterial diversity on chicken carcasses and the processing and storage environments is still relatively unclear and requires more detailed mapping. Doing this can provide insights into improving chicken meat safety and quality.

Based on previous findings (8), the present study, at a pilot scale, aimed to more intensively examine samples through the steps of chicken carcass processing and subsequent chilled storage (Fig. 1) in order to reveal whether there are any connections between bacterial distribution on the chicken products and the processing environment, in particular to better define what contamination occurs throughout processing, and to determine which processing steps or environmental sources substantially impact and/or alter the bacterial diversity. Furthermore, we sought to determine whether different processing equipment or processes have an impact on the bacterial diversity of products through processing and during chill storage in order to predict impact on product shelf life. As a result, approaches taken here included the culture-independent 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequencing to monitor the changes of bacterial diversity on chicken carcasses and the linkage to the local processing environment. Additional support of culture-based aerobic plate counts (APC), and enumeration of Campylobacter and Pseudomonas were also obtained as key foodborne pathogens that were of interests to the poultry industry to understand the safety and quality of chicken products.

FIG 1.

Diagram illustrating the Australian poultry processing line investigated and the stages (highlighted in gray boxes) at which samples were collected. Ten birds were collected from the prescald, postplucker, pre- and post-immersion chill, and post-air chill processing steps each, as well as 30 birds after packaging for the shelf life study. There were various environmental samples collected throughout the processing, including the scalding water, the immersion chilling water, the air, and the wall surface in the air chilling room.

RESULTS

Microbiological analysis.

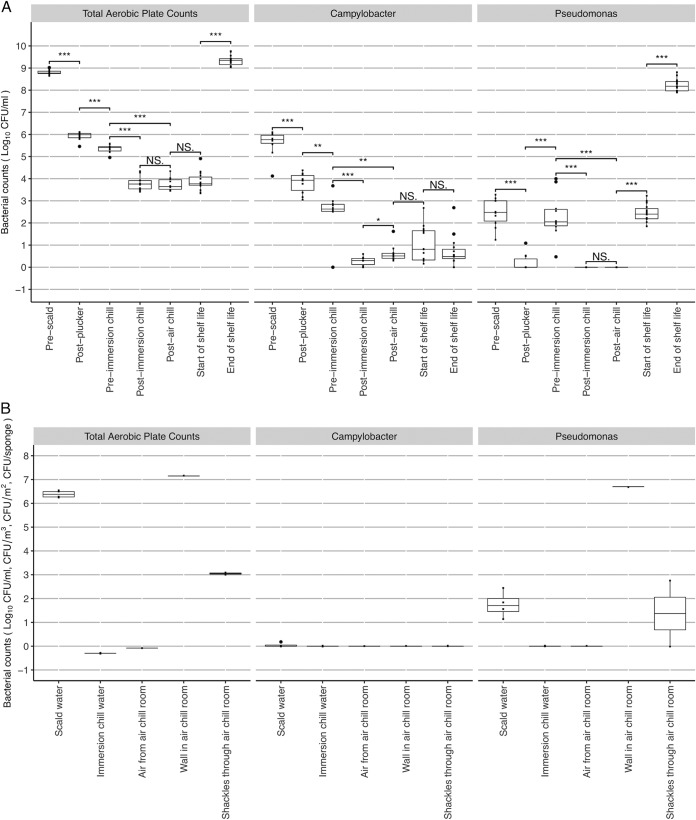

Overall, APC numbers were similar between the processing steps of prescald (8.81 ± 0.11 log10 CFU/ml) and end of shelf life (9.34 ± 0.22 log10 CFU/ml) (Fig. 2A; see also the details in Table S1 in the supplemental material). Campylobacter reduced by nearly 5 log10 CFU/ml (P < 0.001) to 0.70 ± 0.65 log10 CFU/ml, and Pseudomonas increased by nearly 6 log10 CFU/ml (P < 0.001) to 8.23 ± 0.27 log10 CFU/ml after comparing the counts between prescald and end of shelf life (Fig. 2A; for details, see Table S1).

FIG 2.

Bacterial counts of total aerobic plate counts, Campylobacter, and Pseudomonas on chicken carcasses through the processing plant (A, log10 CFU/ml) and from the environmental samples (B, the scald water and immersion chill water in log10 CFU/ml, the air sample in the air chill room in log10 CFU/m3, the air chill room wall in log10 CFU/m2, and the shackles through the air chill room in log10 CFU/sponge). *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; NS, not significant.

In the processing sample group, between the processes of scalding, defeathering, and plucking (i.e., the prescald versus postplucker processing steps) (see Fig. 1), the APC and the counts of Campylobacter and Pseudomonas on chicken carcasses declined significantly by more than 1.8 log10 CFU/ml (P < 0.001, Fig. 2A). There were significant decreases in both APC and Campylobacter (P < 0.01), by 0.58 and 1.53 log10 CFU/ml, respectively, while Pseudomonas increased significantly by 2.1 log10 CFU/ml between the postplucker and pre-immersion chill steps (Fig. 2A), which represent the processes of evisceration and inside/outside washing (Fig. 1). Similar to the results between the prescald and postplucker steps, the process of immersion chilling (pre-immersion chill versus post-immersion chill, Fig. 1) led to a >1.5-log10 CFU/ml reduction of APC, Campylobacter and Pseudomonas (P < 0.001, Fig. 2A), where the Pseudomonas count dropped to below the limit of detection. In contrast to the previous processes, there were no significant reductions on chicken carcasses after exposure to air chilling for either APC (3.76 ± 0.28 log10 CFU/ml) or Campylobacter (0.63 ± 0.36 log10 CFU/ml), and Pseudomonas remained undetectable. In fact, there was a recorded increase in Campylobacter (0.35 log10 CFU/ml) on chicken carcasses after air chilling (P < 0.05, Fig. 2A).

In the shelf life sample group, after chicken carcasses were packaged and stored at 4°C for 1 day (representing the beginning of shelf life, “kill+1”), APC and Campylobacter remained relatively consistent compared to that on the post-air chill samples, which were 3.88 ± 0.39 and 1.01 ± 0.75 log10 CFU/ml, respectively. However, the Pseudomonas count increased significantly from undetectable to 2.44 ± 0.39 log10 CFU/ml (P < 0.001, Fig. 2A). At the end of shelf life (kill+12), APC and Pseudomonas increased significantly to 9.34 ± 0.22 and 8.23 ± 0.27 log10 CFU/ml, respectively, whereas Campylobacter persisted at 0.70 ± 0.65 log10 CFU/ml (Fig. 2A).

In the environmental sample group, the APC were determined to be 6.38 ± 0.13 log10 CFU/ml, Campylobacter levels were determined to be 0.05 ± 0.08 log10 CFU/ml, and Pseudomonas levels were determined to be 1.75 ± 0.48 log10 CFU/ml in the scalding water, whereas the counts were at or below detection limits in the immersion chilling water (Fig. 2B). Campylobacter was not detected in any of the environmental samples from the air chilling room, and there were no counts for either APC or Pseudomonas in the air circulating within the air chilling room (Fig. 2B). However, 7.15 and 6.70 log10 CFU/m2 were detected on the air chilling room wall for APC and Pseudomonas, respectively. In addition, 3.05 ± 0.05 and 1.37 ± 1.37 log10 CFU/sponge were recorded for APC and Pseudomonas, respectively, from sponges hung on the shackles within the air chilling room (Fig. 2B).

Figure 3 shows the prevalence of Campylobacter across all sampling points. For the sample groups of processing and shelf life, the Campylobacter prevalence reduced from 100% at the prescald samples to 87% at the end of shelf life. In the remaining sampling points, Campylobacter remained prevalent and viable on all samples at most sampling points, with 80% prevalence on both pre- and post-immersion chill samples. For the environmental samples, one sample of 2 liters of scalding water was identified as having C. jejuni present (Table S2). Campylobacter was not detected in any other environmental samples. With a total of 427 Campylobacter colonies isolated from all 92 samples, C. coli was only isolated from the start of shelf life samples (2.7% of Campylobacter colonies) and the end of shelf life samples (15.6% of Campylobacter colonies) (Table S2).

FIG 3.

Prevalence of Campylobacter across all sampling points.

Bacterial diversity analysis.

In total, 7,217,858 unique sequencing reads were obtained across all 92 samples. We found that 36,408 reads per sample were rarefied and subsampled (3,349,536 reads after rarefaction, representing 46.41% of total unique reads). Then, 756 operational taxonomic units (OTUs) were taxonomically assigned from phylum to genus level, which represented 91.4% coverage of the bacterial diversity in this study.

Alpha diversity metrics.

Key alpha metrics of bacterial diversity for each sampling point are shown in Table 1. Overall, the bacterial diversity on chicken products from the beginning of processing to the end of shelf life declined dramatically, comparing the prescald step to the end of shelf life step, including species richness (d, from 78.2 to 25.4), Pielou’s evenness (J′, from 0.5 to 0.1), and Shannon diversity (H′, from 3.1 to 0.5), respectively.

TABLE 1.

Summary of bacterial diversity metrics of samples

| Sample group | Sampling point | No. of phylaa | No. of generab | Species richness (d) | Pielou’s evenness (J′) | Shannon diversity (H′, loge) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Processing | Prescald | 18 | 361 | 78.2 | 0.5 | 3.1 |

| Postplucker | 17 | 330 | 71.4 | 0.5 | 2.8 | |

| Pre-immersion chill | 15 | 330 | 71.4 | 0.5 | 2.7 | |

| Post-immersion chill | 16 | 346 | 74.9 | 0.5 | 2.7 | |

| Post-air chill | 17 | 363 | 78.6 | 0.4 | 2.4 | |

| Shelf life | Start of shelf life | 20 | 452 | 97.9 | 0.4 | 2.5 |

| End of shelf life | 10 | 118 | 25.4 | 0.1 | 0.5 | |

| Environmental | Scald water | 11 | 186 | 40.2 | 0.2 | 1.3 |

| Immersion chill water | 16 | 323 | 69.9 | 0.5 | 2.7 | |

| Air from air chill room | 18 | 285 | 61.7 | 0.5 | 2.8 | |

| Wall in air chill room | 9 | 104 | 22.4 | 0.3 | 1.2 | |

| Shackles through air chill room | 16 | 360 | 78.0 | 0.5 | 2.8 | |

| Total | 29 | 756 | 163.9 | 0.4 | 2.9 |

The number of phyla identified for each sampling point.

The number of genera identified for each sampling point.

Between the five processing steps, species richness (d) was only slightly altered with no overall change between the prescald (78.2) and the postplucker (71.4) sample sets. Pielou’s evenness (J′) was also relatively consistent (0.4 to 0.5) for each sampling point. However, Shannon diversity (H′) continuously declined at each sampling point of the processing line, starting at 3.1 in the prescald samples dropping to 2.4 in the post-air chill samples. For the shelf life-related samples, a dramatic decline in diversity was observed for all alpha diversity metrics over the 12-day period. During shelf life, the species richness (d) decreased from 97.9 to 25.4, Pielou’s evenness (J′) dropped from 0.4 to 0.1, and Shannon diversity (H′) dropped from 2.5 to 0.5, respectively. For the environmental samples, the air chill room wall had relatively low species richness (d, 22.4) and Shannon diversity (H′, 1.2) compared to other environmental samples. Immersion chill water, air from the air chill room, and shackles moving through the air chill room showed a species richness (d) of 61.7 to 78.0, an evenness (J′) of 0.5, and a Shannon diversity (H′) of 2.7 to 2.8. Scald water also showed greater species richness (d, 40.2) and about the same Shannon diversity (H′, 1.3) as the air chill room wall, but it had less Pielou’s evenness (J′, 0.2). The prescald samples exhibited the greatest Shannon diversity (H′, 3.1) compared to all other sampling points, even greater than the totaled samples (H′, 2.9). In addition, there was an increase in all alpha diversity metrices noted between the sampling points of post-air chill and start of shelf life (Table 1). Overall, the greatest loss of diversity occurred during storage, as shown for the shelf life samples.

Changes of bacterial diversity at phylum and genus levels.

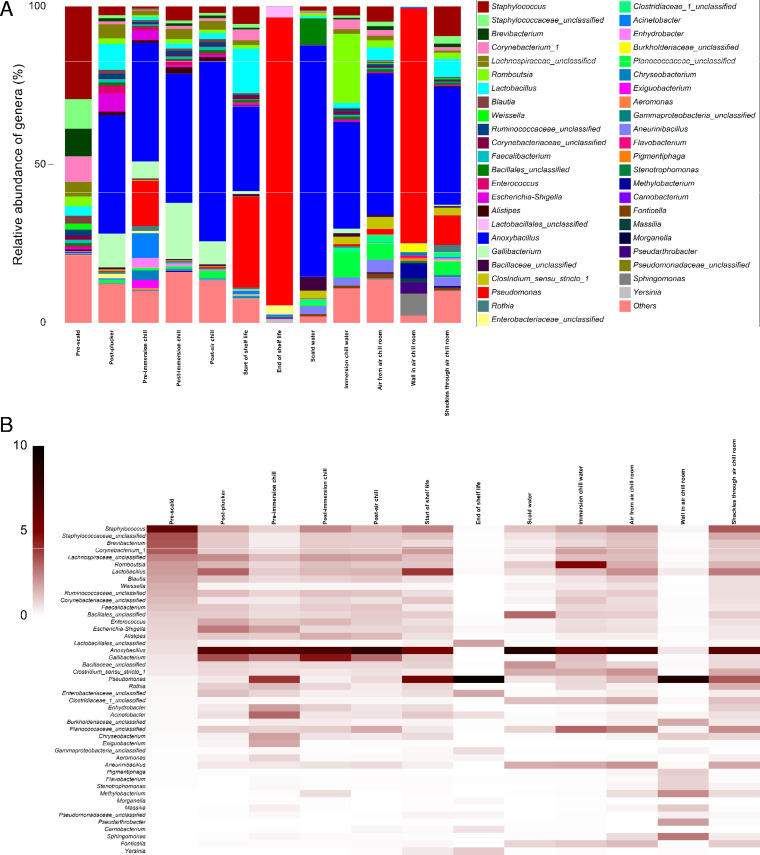

The changes of identified taxa (genus level) paralleled the changes in species richness across the sampling points (Table 1). To better understand the correlation of the bacterial diversity between the chicken carcasses and the processing environment, the bacterial diversities between sampling points are illustrated at the phylum level in Fig. 4 (see details in Table S3 in the supplemental material). In addition, the 10 most abundant taxa at the genus level from each sampling point were selected and pooled to form a table of 46 taxa which represent at least 78.7% of the bacterial community and demonstrate the changes of the bacterial diversity through processing (Fig. 5; see details in Table S4 in the supplemental material). A complete list of 756 OTUs of each individual sample is given in Table S5.

FIG 4.

Relative abundances of the four most abundant taxa at the phylum level across all sampling points.

FIG 5.

Relative abundances of 46 taxa pooled from the 10 most abundant taxa at each sampling point in a bar plot (A) and a shade map (B). The order of the 46 taxa is descending according to their respective relative abundance in the prescald step.

Overall, Firmicutes, Actinobacteria, Bacteroidetes, and Proteobacteria were the four most abundant phyla, ranging between 98.2% in both post-immersion chill and post-air chill samples and nearly 100% in the end of shelf life samples (Fig. 4). Firmicutes was the most dominant phylum across most of the sampling points, representing at least 54.3% ± 31.8% relative abundance in the pre-immersion chill samples, decreasing to 3.8% ± 4.4% in the end of shelf life samples and 0.6% ± 0% in the air chill room wall samples (Table S3). Proteobacteria dominated in the end of shelf life samples and the air chill room wall, which represented 96.1% ± 4.4% and 92.6% reads, respectively (Table S3).

The bacterial diversity at the genus level illustrated greater and more complicated changes between various sampling points. However, the relative abundance of Campylobacter across all samples was <0.5% in the bacterial community, with one exception where one of the start of shelf life samples showed a 2.6% relative abundance (Table S5).

Between prescald and postplucker, which effectively incorporates the impacts of processes of scalding, defeathering and plucking (Fig. 1), Staphylococcus on average had the greatest decrease in the relative abundance compared to any other taxa, by 8-fold reduction (from 29.3% ± 9.3% to 2.8% ± 2.4%, P < 0.001). In contrast, Anoxybacillus and Gallibacterium increased dramatically by 127-fold (from 0.3% ± 0.2% to 37.4% ± 23.4%, P < 0.01) and 53-fold (from 0.2% ± 0.3% to 10.7% ± 13.4%, P < 0.01), respectively, between the prescald and postplucker steps. Anoxybacillus dominated the bacterial community of the scalding water with a relative abundance of 73.0% ± 1.3%.

Between the postplucker and pre-immersion chill steps, the impacts of evisceration and inside/outside washing processes were assessed on diversity (Fig. 1). There was a dramatic increase of Pseudomonas reads by 70-fold, from 0.2% ± 0.3% to 14.3% ± 18.5% (P < 0.01), whereas Anoxybacillus abundance remained relatively consistent at approximately 37.5% ± 31.9%.

Following chilling processes (pre-immersion chill versus post-air chill) on carcasses, although statistically insignificant, Pseudomonas declined to become a minor component in the bacterial community after immersion chilling (from 14.3% ± 18.5% to 0.1% ± 0.1%) and then remained relatively unchanged through air chilling. Gallibacterium increased from 5.3% ± 8.8% to 17.7% ± 28.1% after immersion chilling before decreasing to 7.3% ± 15.9% after air chilling. Anoxybacillus gradually increased and remained as a dominant taxon through both chilling processes, increasing from 37.5% ± 38.5% to 40.9% ± 39.4% after immersion chilling and then up to 56.8% ± 35.8% after air chilling. The relative abundance of Romboutsia was much higher (P < 0.001) in the immersion chill water (21.9% ± 2.1%) than in the samples from the air chilling room, which included 2.2% in the air, 0.03% on the wall surface and 1.9% ± 0.3% on the sponges hung on the shackles. Anoxybacillus remained at a dominant level in most of the environmental samples during chilling, being 33.6% ± 0.3% in the immersion chill water, 44.7% ± 0% in the air sample, 37.2% ± 9.5% on the sponges hung on the shackles. In comparison, Pseudomonas represented a small proportion of the bacterial community in most of the environmental samples in chilling but was the most dominant genus on the wall surface (74.2%).

Thirty packaged carcasses were collected for shelf life testing and were stored at 4°C over 12 days. Notably, the relative abundance of Firmicutes decreased from 79.7% ± 21.7% at the post-air chill step to 56.6% ± 25.3% at the start of shelf life while Proteobacteria increased from 10.5% ± 16.7% to 33.2% ± 22.7%. After 12 days of storage, Firmicutes and Proteobacteria collectively represented close to 100% of the bacterial community with relative abundances of 3.8% ± 4.4% and 96.1% ± 4.4%, respectively. At the genus level, Pseudomonas and Anoxybacillus were the two dominant taxa on carcasses at the beginning of the shelf life, representing 28.6% ± 21.3% and 26.6% ± 32.4% of the bacterial community. By comparison, these two taxa made up 0.5% ± 0.7% and 56.8% ± 35.8% of the bacterial community on carcasses in the post-air chill samples, respectively. There was also an increase of 12.1% for the relative abundance of Lactobacillus at the beginning of the shelf life from 1.9% ± 1.8% in post-air chill. Similar to the bacterial diversity on the wall of the air chill room, Pseudomonas (91.0% ± 10.2%) was the predominant taxon on the carcasses at the end of shelf life. Anoxybacillus, as one of the dominant taxa at the beginning of the shelf life, was virtually not detected with between 0 and 3 reads detected per 36,408 sequence reads per sample at the end of shelf life (Table S5).

Beta diversity and correlations between sampling points.

Figure 6 illustrates the correlations between sampling points to assist in understanding the impact of processing interventions on the bacterial diversity through processing. Figure 6A illustrates the distribution of all individual samples based on the proportions of 756 taxa using principal coordinate analysis (PCoA). Apart from the end of shelf life and the air chill room wall samples, samples from other sampling points overlapped each other. In order to better discriminate the sampling points that were closely related, Fig. 6B was generated by using the weighted Spearman rank correlation to evaluate all 756 taxa, which were bootstrapped at 95% intervals to analyze their correlations on a metric multidimensional scale (MDS). The post-immersion chill and post-air chill samples were the most similar, in accordance with the proportion of genera present within these samples (Fig. 6B). Since the 46 taxa pooled from the 10 most abundant taxa from each sampling point represented at least 78.7% of the bacterial diversity, a PCoA with the diversity similarity clustering was conducted (Fig. 6C) to determine whether the 46 taxa could represent the entire bacterial diversity on chicken products. Similar to what is shown in Fig. 6A, the end of shelf life and the air chill room wall samples were distinctive from the remaining sampling points as were the prescald and scald water samples. However, unlike what is shown in Fig. 6A and B, all the remaining sampling points based on 46 taxa (Fig. 6C) were clustered at 60% similarity, demonstrating different clustering patterns of the sampling points between all 756 taxa (Fig. 6A and B) and the 46 taxa. Within the 60% similarity group, the bacterial diversity on samples from the air in air chill room and from the air chill room shackles were more than 80% similar. The same observation was found for the postplucker, post-immersion chill, and post-air chill samples among which post-immersion chill and post-air chill were also closely related as shown in Fig. 6B.

FIG 6.

Distribution and correlations between sampling points. The circular shape (•) represents the processing sample group, the square shape (☐) represents the shelf life sample group, and the cross shape (+) represents the environmental sample group. Dark blue represents samples from the prescald step, light red represents samples from the postplucker point, light green represents samples from the pre-immersion chill point, purple represents samples from the post-immersion chill point, light blue represents samples from the post-air chill point, medium green represents the start of shelf life point, dark red represents the end of shelf life point, gray represents samples from the scald water point, dark green represents the immersion chill water point, black represents the air in the air chill room point, orange represents the air chill room wall point, and dark yellow represents the shackles through the air chill room point. (A) PCoA of all the 92 samples based on all identified taxa at genus level using the Bray-Curtis coefficient. Each shape with a different color represents one sample at its respective sampling point. (B) Metric MDS of sampling points after they were determined by bootstrapping samples at 95% confidence intervals on a weighted spearman rank correlation. (C) PCoA of all the sampling points based on the 46 taxa pooled from the 10 most abundant taxa in each sampling point to identify the similarity level between sampling points. Each shape with a different color represents a sampling point in its respective sample group. The dotted and solid circles indicate the sampling points were clustered at 80 and 60% similarity levels based on their bacterial diversity, respectively.

DISCUSSION

The present study revealed the effectiveness of the processing line in reducing the numbers of APC, Campylobacter, and Pseudomonas on chicken carcasses (P < 0.001), which supports results previously published from a different processing line in Australia (8). The inability to completely eliminate Campylobacter prevalence and the limited effect of air chilling on carcass bacterial reduction were also in agreement with the previous study (8). The present study focused on the impact of environmental attributes surrounding the chicken carcasses during processing with the aim to identify processing environmental microorganisms that cross-contaminate chicken carcasses. However, the culture-based approach was not able to provide comprehensive information to assess the linkage between the carcass contamination and the environmental attributes.

By utilizing the 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequencing in this study, the most identified bacterial taxa at the phylum level across all sampling points were Firmicutes, Proteobacteria, Actinobacteria, and Bacteroidetes, aligning with previous studies regardless of sequencing techniques, sampling approach, geographic locations of processing plants, flocks of chicken, etc. (8, 9, 11–14). In this study, Firmicutes was the predominant phylum from most of the sampling points, except for chicken carcasses at the end of shelf life and the air chill room wall samples on which Proteobacteria dominated, making up at least 92% of the bacterial diversity. Despite Campylobacter being recognized as a major cause of human gastrointestinal disease, its relative abundance in the bacterial community on the chicken carcasses persisted at a very low level, even though the counts were reduced by about 5 log10 CFU/ml throughout processing. These findings align with the previous finding (8). However, it is important not to neglect the epidemiological impact of Campylobacter because it is known that the dose of Campylobacter can be as low as 500 cells to cause human diseases (16, 17).

From the prescald to the postplucker steps, the processes of scalding, defeathering, and plucking were unable to affect the Campylobacter prevalence, in contrast to a 30% reduction after scalding in the previous study (8). The difference between the two studies may be due to potential cross-contamination from defeathering and plucking in the sampled processing plant of this study, which has been reported previously based on the microbiological analysis (18). The increased Proteobacteria relative abundance in this study suggested potential cross-contamination sources between the prescald and postplucker steps, which is supported by two 16S rRNA gene amplicon studies of poultry processing plants in the United States (12, 14). All of these findings suggest that the physical processes of scalding, defeathering, and plucking could be responsible for the increase of Proteobacteria during poultry processing. At the genus level, Anoxybacillus was noted to become an important component in the bacterial community between the prescald and postplucker processing steps, both on chicken carcasses and in the scalding water in this study, supporting previous findings which highlighted the importance of Anoxybacillus in scalding water (13). In comparison, no Anoxybacillus sequence reads were detected at the prescald step and only six reads were identified on chicken samples from the postscald step in a previous study (8). Anoxybacillus is recognized to cause food spoilage, e.g., a common contaminant of dehydrated milk powder products (19–21), although it is a thermophilic spore-forming microorganism that is usually isolated from hot springs (22). The difference in findings between this study and the previous study (8) could be due to the processing environment, sampling time of the day for the scalding water, particular sampling points, or different processing equipment. The previous study sampled the chicken carcasses from pre- and postscald, whereas this study collected samples from prescald and postplucker because the sampled processing line had a confined tunnel system that incorporated scalding, defeathering, and plucking together. The confined tunnel may have an elevated temperature and a high humidity, providing conditions that favor the growth of Anoxybacillus, possibly in the form of a biofilm (20, 23). Campylobacter also prefers warm conditions with a relatively high humidity (24). As a result, the confined tunnel may act as an important cross-contamination point that results in carcasses being exposed to Anoxybacillus and also allowing for Campylobacter survival. This hypothesis is supported by several findings in this study, for example the linkage between the 25% Campylobacter prevalence in the scalding water and the persistent Campylobacter prevalence on chicken carcasses, as well as the observed dominant Anoxybacillus (73.0%) in the scalding water and the high number of Anoxybacillus reads detected directly from chicken carcasses.

Between postplucker and pre-immersion chill where the processes of evisceration and inside/outside washing exist (Fig. 1), a significant increase in Pseudomonas (P < 0.01) was noted both in the microbiological counts and the bacterial diversity, whereas the APC and Campylobacter counts decreased. A similar increase of Pseudomonas relative abundance was also observed in the previous studies (8, 12), although sampling points varied. This suggests Pseudomonas either survives better than other microorganisms during evisceration and washing or there may be routes introducing Pseudomonas. In addition, a previous study investigated impacts of the water pressure, the amount of water, and the length of the washing step utilized during chicken carcasses processing, which concluded that Pseudomonas, unlike other microorganisms, was least affected by the washing process. Depending on how the washing step was set up, the Pseudomonas number could even increase (25). Cold water is usually used during inside/outside washing after evisceration and before immersion chilling (17). Due to the psychrotolerant nature of Pseudomonas, the washing step with cold water may enhance the survival of Pseudomonas compared to other bacteria. Some previous studies also investigated the water supply as the contamination source for Pseudomonas on to chicken carcasses (26), as well as Acinetobacter (27), which was also found to increase in relative abundance from the postplucker (0.3%) to pre-immersion chill (7.9%) steps in this study. Anoxybacillus was still the predominant taxa at genus level, indicating an ability to persist through the combination of evisceration and washing. The reason could be that the opened follicles during scalding encapsulate Anoxybacillus (vegetative cells and/or spores) after the temperature dropped during washing with cold water; however, it requires further study to validate this.

The chilling process, including immersion chilling and air chilling, was a major focus of this study, based on previous findings (8). Despite the reduction of Campylobacter counts on carcasses through immersion chilling, the prevalence of Campylobacter was unaffected which was similar to the findings of the previous study, as well as the limited impact of air chilling (8). However, the Campylobacter counts in all the environmental samples were at or below the limit of detection. Thus, the culture-based approach was not able to explain why the Campylobacter prevalence persisted through the immersion chilling at 80% level and increased to 100% through air chilling. This could be partly due to probabilities associated with low Campylobacter cell numbers likely resulting in chances of nondetection. However, APC and Pseudomonas levels were below the limit of detection in the immersion chilling water and air sample taken from the air chill room, which could be due to the chlorine impact in the immersion chilling as Australia allows up to five parts per million of free available chlorine during immersion chilling (28). A previous study suggested the total bacterial population will normally be at a very low level (∼102 copies/ml) (29) due to the action of chlorine in the chilling tank to reduce bacterial contamination (30, 31).

The bacterial diversity results offered a deeper and more comprehensive perspective of the relations of bacterial diversity between the chicken carcasses and the processing environment and is able to contrast different poultry production facilities. With the processes of immersion chilling and air chilling together, this study showed a gradual but consistent change of the bacterial diversity on chicken carcasses through the chilling process. In this study, Pseudomonas became a minor component (<0.5%) of the bacterial community on chicken carcasses after immersion chilling and air chilling. Similarly, the counts of Pseudomonas on carcasses after immersion chilling and air chilling were below the limit of detection. The low proportion of Pseudomonas after immersion chilling was also noted in two recent studies (8, 9). However, the previous study (8) demonstrated a great change of the bacterial diversity through air chilling which the relative abundance of Pseudomonas in the bacterial community on carcasses increased from 0.3% to 20.3% (P < 0.001). In addition, Anoxybacillus persisted as a dominant taxon on carcasses throughout chilling in this study.

The findings of bacterial diversity on chicken carcasses were supported when examining the bacterial diversity present in the environmental samples around the chilling process. Both the present study and the previous one (9) highlighted the immersion chilling water as an important cross-contamination source by comparing the bacterial diversity in the immersion chilling water with that on the chicken carcasses. Anoxybacillus gradually increased and remained at a high level of relative abundance, suggesting an accumulation and redistribution of this taxon between chicken carcasses by the immersion chilling water and from the air blown at a high rate onto chicken carcasses. However, the different relative abundances of Romboutsia between the immersion chilling water and the air sample was noted. Thus far, little is known about this particular taxon, which was previously classified as Clostridium (32, 33). The genome and functional analysis of Romboutsia revealed its metabolic capabilities of carbohydrate utilization and fermentation of single amino acids (34), and it has been associated with age of animals and their health status which healthy animals usually have low relative abundance of Romboutsia, e.g., chicken (35), yak (36), and deer (37). In this study, the relative abundance of Romboutsia was <3.1% on various chicken carcasses throughout the sampling points. The high relative abundance of Romboutsia in the immersion chilling water could be due to the accumulation from previous chicken carcasses as the processing day progressed. Romboutsia could then be carried over on chicken carcasses and aerosolized in the air chilling room as it was found in the air sample and in the sponges hung on the shackles, although at low relative abundance.

Given the cold conditions in the air chilling room and the nature of Pseudomonas, the high count and the relative abundance of Pseudomonas on the wall surface in the air chill room are expected. Of the remaining 10 most abundant taxa on the air chill room wall, most taxa are known to include several psychrotolerant species, e.g., Chryseobacterium, Pigmentiphaga, Flavobacterium, Stenotrophomonas, Massilia, Pseudarthrobacter, and Sphingomonas (38–43). These taxa are also often isolated from food production environments or during food spoilage. As shown in a recent study tracking psychrotrophic bacteria through chicken processing, a high count of psychrotolerant bacteria was found on the walls in the chilling room, air samples, and from swabs of food contact surfaces (44). These observations concur with the high count of Pseudomonas found in this study. These data suggest that the contaminated wall in the chilling room could be a source of bacteria which can be transferred onto chicken carcasses. This is aided by the high rate of cold air blowing into the room, which could create aerosols of psychrotolerant bacteria (44). Aerosolized bacteria could contaminate the chicken carcasses in the chilling room, as well as subsequent processing areas, such as cutting and packaging.

Together, the findings of the impact of the immersion chilling and the air chilling on the bacterial diversity on chicken carcasses in this study were different than in the previous study, which showed a greater impact of air chilling than immersion chilling (8). Although other factors may play a role in the difference between studies, e.g., flocks and idiosyncrasies of the processing facility, the main reason may be the parameters of the chilling processes between the two studies. The sampled processing plant in this study used a period of ∼1.5 h during immersion chilling and ∼0.5 h during air chilling, in comparison to the processing plant in the previous study which implemented an ∼0.5-h immersion chilling and an ∼1.5-h air chilling (8). Comparison of the two studies in terms of the chilling parameters and the resulting bacterial diversity indicated that the longer the time that chicken carcasses spent in each chilling, the greater the change in the bacterial diversity may have. Combining findings in this study and the previous one (8), the chilling process is an important control point during processing that may cause cross-contamination to chicken carcasses.

At the beginning of shelf life, the significant increase of Pseudomonas count (P < 0.001) from less than the limit of detection and the prevalence of C. coli from none in any previous sampling points are noteworthy. Similarly, the bacterial diversity showed an increase at both the phylum and genus levels on carcasses between the samples from steps of post-air chill and start of shelf life. These findings suggested there may be potential cross-contamination after air chilling in the cutting and packaging area (Fig. 1), which requires further study to locate the cross-contamination sources. During refrigerated storage, Pseudomonas and Anoxybacillus were the two dominant taxa on chicken carcasses at the beginning of shelf life, but virtually no Anoxybacillus was detected at the end of shelf life after 12-day storage, whereas Pseudomonas became predominant at 91.0%. The high proportion of Pseudomonas at the end of shelf life of chicken meat was expected since it is known to be a main component in the chicken meat spoilage (7) and grows at low temperature.

When analyzing the correlations of sampling points on all 756 taxa, the bacterial diversity was similar on most samples, except the samples from the end of the shelf life and the wall surface in the air chilling room. In particular, samples from the steps of post-immersion chill and post-air chill were highly overlapped, again indicating the limited impact of air chilling on the bacterial diversity on carcasses. Based on the bacterial diversity, the separation of the end of shelf life and the wall surface from most sampling points may be linked to the dominant proportion of Pseudomonas in the bacterial community. Postplucker, post-immersion chill, and post-air chill step samples revealed a high similarity level (80%) in terms of bacterial diversity partly driven by cross-contamination with Anoxybacillus when analyzing the 46 taxa pooled from the 10 most abundant taxa in each sampling point. Chicken carcass follicles encapsulating Anoxybacillus due to cold water used in the washing step is theorized to carry over Anoxybacillus to the following processing steps, as well as other microorganisms contained in the residual water on the chicken carcasses. The hypothesis is supported by the large proportion of Anoxybacillus in the bacterial community which was continuously detected in the processing environment. Given the scalding water is the major contributor of Anoxybacillus during processing, the nature of Anoxybacillus, and the confined tunnel of the processing equipment may undesirably select and distribute the thermophilic bacteria. In addition, the large group of sampling points clustered at the similarity level of 60% supported the importance of the scalding water and the impact of the confined tunnel in the processing. This suggests that whatever bacterial diversity resides on the chicken carcasses after scalding potentially impacts all the remaining processes. Hence, this indicates that the importance of changing the scalding water on a regular basis, a good hygiene practice during processing, and a thorough disinfection of the confined tunnel at the end of processing day are all critical. However, a study to investigate the two types of processing equipment to confirm these observations with a wider range of facilities seems required.

Conclusions.

The sampled poultry processing plant had processes effective in reducing the bacterial load on chicken carcasses. However, Campylobacter remained prevalent, indicating the limitation of current processing interventions for eliminating Campylobacter. With the help of 16S rRNA gene sequencing technique, this study was able to demonstrate that each processing intervention may introduce contamination of microorganisms at different levels. In particular a confined tunnel system incorporating scalding, defeathering and plucking may have an undesirable effect of selecting and distributing the thermophilic bacteria between chicken carcasses, e.g., Anoxybacillus. The chilling process was another important step for cross-contamination in distributing psychrotolerant bacteria, such as Pseudomonas. Depending on the parameter of the processing equipment, the immersion chilling may have a greater impact than the air chilling in redistributing microorganisms on chicken carcasses which could then influence the meat quality during subsequent storage and thus affect shelf life. While this study was at a pilot scale of one type of processing line, it is very useful to provide a deep understanding of how the processing equipment and processing interventions distribute microorganisms, as well as offering a comprehensive view into the change of the bacterial diversity on chicken carcasses from the beginning of processing all the way to the end of shelf life. Lastly, some studies to evaluate the impact of the confined tunnel of incorporating scalding, defeathering, and plucking seem necessary, as well as further surveys to investigate the cutting and packaging area to locate potential cross-contamination sources.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sample collection.

A single flock of chickens were sampled within a poultry processing plant at a pilot scale in Australia. Random chicken carcasses (n = 10) were collected at five distinct processing steps each (Fig. 1), which included the prescald, postplucker, pre-immersion chill, post-immersion chill, and post-air chill steps. Similar to the sampling approach of Chen et al. (8), each chicken carcass collected from five processing steps was placed in a stomacher bag (38 cm × 50 cm; Sarstedt, South Australia, Australia) immediately after collection from the processing line. A volume of 500 ml of buffered peptone water (BPW; Oxoid) was added to the stomacher bag immediately after chicken carcasses were collected from the processing line, regardless of the carcass weight. The carcasses were then thoroughly agitated by hand for 2 min to ensure the surface, internal, and external parts of the birds were fully contacted with BPW. The carcass rinsate (∼400 ml) was transferred into two 250-ml presterilized jars with lids (Sarstedt). Thirty additional chicken carcasses from the same flock were also collected at the end of the processing after they were packaged for the shelf life study.

Several environmental samples within the processing plant were collected. These included the scald water, immersion chill water, air samples containing bacterial cells collected from within the air chill room and the wall surface in the air chill room. Briefly, 8 liters of scald water and 8 liters of immersion chill water sampled into four presterilized 2-liter bottles each, and 200 μl of 0.1 M sodium thiosulfate was added into each 2-liter bottle containing immersion chill water soon after they were collected at the plant to neutralize any residual free available chlorine. Up to nine cubic meters of air in the air chill room was collected by running a Coriolis μ biological air sampler (Bertin Instruments, Montigny-le-Bretonneux, France) for 30 min according to the manufacturer’s instruction. This resulted in a final sample volume of ∼15 ml with air material suspended in BPW. Twelve presterilized Whirl-Pak Speci-Sponges (Nasco, Fort Atkinson, WI) were filled with 25 ml of BPW in the laboratory prior to sampling in the processing plant. Two sponges were used to swab the air chill room wall surface, each of which swabbed one square meter. They were pooled as one sample for the air chill room wall. The remaining 10 sponges were hung on random empty shackles to collect bacteria potentially depositing on chicken carcass surfaces during the air chilling step, which had an approximate duration of 30 min. Each shackle surface was sterilized with 80% ethanol before hanging the sponges. Ten sponges collected from shackles were stored in two sealed bags, which were consequently considered as two pooled samples.

In total, 50 chicken carcass rinsates from the five distinctive processing steps, 30 chicken carcasses for shelf life study, and 12 environmental samples were all stored on ice for transportation to the laboratory within 3 h of sampling at the plant. These 92 samples were classified into three sample groups: (i) a processing group that included 10 carcass-derived samples from the prescald, postplucker, pre-immersion chill, post-immersion chill, and post-air chill steps each, respectively; (ii) an environmental group that included samples from the scald water (n = 4), immersion chill water (n = 4), an air sample from the air chill room (n = 1), a wall sample from air chill room (n = 1), and pooled shackle samples from air chill room (n = 2); and (iii) a shelf life group that included 15 samples each from start and end of shelf life (two time points).

Sample preparation.

All samples were processed immediately after arrival in the laboratory for culture-based analysis (Table 2). Briefly, for samples collected by sponges, another 25 ml of BPW was added to each Whirl-Pak Speci-Sponge. Each sponge was then homogenized for 1 min, and the resulting BPW containing bacterial cells was collected into 250-ml presterilized jars with lids.

TABLE 2.

Sample preparation

| Sample group | Sampling point | No. of samples | Vol collected (ml)/sample | Vol (ml) used for culture-based analysis/sample | Campylobacter enrichment (10 ml/sample) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Processing | Prescald | 10 | 500 | 20 | No |

| Postplucker | 10 | 500 | 20 | No | |

| Pre-immersion chill | 10 | 500 | 20 | No | |

| Post-immersion chill | 10 | 500 | 20 | Yes | |

| Post-air chill | 10 | 500 | 20 | Yes | |

| Shelf life | Start of shelf life | 15 | 500 | 20 | Yes |

| End of shelf life | 15 | 500 | 20 | Yes | |

| Environmental | Scald water | 4 | 2,000 | 10 | Yes |

| Immersion chill water | 4 | 2,000 | 10 | Yes | |

| Air in air chill room | 1 | 15 | 2 | No | |

| Wall in air chill rooma ,b | 1 | 100 | 10 | Yes | |

| Shackles in air chill rooma ,c | 2 | 400, 600 | 10 | Yes |

Samples collected by using sponges. An additional 25 ml of BPW was added to each Whirl-Pak Speci-Sponge in the laboratory after sampling, yielding a mixture of 50 ml/sponge.

Two sponges swabbed the air chill room wall were pooled as one sample.

Ten sponges hung on random empty shackles moving in the air chill room, which were collected into two sealed bags. Due to time and practice in the air chill room during sampling, one bag contained four sponges, and the other contained six sponges. Consequently, this resulted in two samples collected with volumes of 400 and 600 ml, respectively.

A volume of 30 ml of rinsate per chicken carcass and 20 ml per environmental sample were transferred to a 50-ml Falcon tube (Sarstedt) for the enumeration of APC, Campylobacter, and Pseudomonas, with the exception of only 2 ml of the air sample from the Coriolis μ biological air sampler taken for the microbiological counts. All remaining carcass rinsates and all remaining environmental samples were stored at 4°C and then centrifuged in Falcon tubes at 5,500 × g for 10 min at 4°C (Sigma, catalog no. 4K15), supernatant removed, and the pellet then stored at –80°C for the bacterial diversity analysis. The centrifugation was carried out within 30 h after sampling from the poultry plant.

For the shelf life testing, 30 packaged chicken carcasses were stored at 4°C. Fifteen carcasses were rinsed and agitated using the approach described above on the following day after collection (kill+1) and represented the start of shelf life. The remaining 15 carcasses were processed 12 days after collection (kill+12) and were considered the end of shelf life. The time frame and storage conditions replicated the commercial poultry processors in storing and distributing the chicken products based on the recommendation from the poultry facility sampled.

Microbiological analysis.

(i) Enumeration of APC. All samples were diluted in BPW and plated onto 3M aerobic plate count PetriFilm for APC (3M Health Care, St Paul, MN) enumeration and incubation according to the manufacturer’s instructions. In case there were no colonies present from the diluted samples, all samples were also plated out using the undiluted samples. Colonies were enumerated, and the numbers were logarithmically transformed as the log10 CFU/ml at each dilution. Any plates that had no colonies at the respective dilution were assigned a value of 0.5 colony and then logarithmically transformed as log10 CFU/ml. Therefore, the limit of detection of APC was −0.30 log10 CFU/ml for samples in the groups for processing and shelf life, as well as the scald water and immersion chill water in the environmental group. The limits of detection were set at −0.08 log10 CFU/m3 for the air sample collected by the Coriolis μ biological air sampler from the air chill room, 1.70 log10 CFU/m2 for samples from the air chill room wall, and 1.40 log10 CFU/sponge for samples from air chill room shackles.

(ii) Campylobacter enumeration and species identification. The Campylobacter enumeration followed previous published protocols (8, 28) by plating serial dilutions onto modified charcoal cefoperazone deoxycholate agar (mCCDA; Oxoid) plates with antibiotics (Oxoid). To further maximize detection of Campylobacter, 3 ml of rinsate of each sample from post-immersion chill, post-air chill, all shelf life samples, and all environmental samples, except for the air samples from the Coriolis μ biological air sampler, was spread onto six mCCDA plates (500 μl of rinsate per plate). In addition, 100 μl of undiluted rinsate and the first 1 in 10 diluted rinsate were plated onto mCCDA. All mCCDA plates were incubated at 42°C for 48 h under 5% CO2 atmosphere generated within a CB150 incubator (Binder, Tuttlingen, Germany). Colonies were reported as the log10 CFU/ml at each dilution. Any plates that had no colonies at respective dilution were treated as a half colony.

From 30 ml of rinsate per chicken carcass and 20 ml per environmental sample stored in 50-ml Falcon tubes for the culture-based analysis, 10-ml aliquots per sample in post-immersion chill, post-air chill, and all environmental samples, except for the air sample from the Coriolis μ biological air sampler, were taken. They were used for Campylobacter enrichment and then plated out onto mCCDA plates in order to maximize the Campylobacter detection, which is similar to previous studies (8, 28).

Up to 10 random Campylobacter presumptive positive colonies from each sample were selected, and species were differentiated by PCR (45). All PCR products were separated on a 2% (wt/vol) agarose gel and stained with ethidium bromide before visualization under UV light (Gene Genius; Syngene, Cambridge, UK). The PCR results were used to adjust the recorded Campylobacter counts as necessary. Therefore, the limit of detection of Campylobacter was 0 log10 CFU/ml for samples in the groups of processing and shelf life, as well as the scald water and immersion chill water in the environmental group. The limits of detection were set at 0 log10 CFU/m3 for the air sample collected by the Coriolis μ biological air sampler from the air chill room, 0 log10 CFU/m2 for samples from the air chill room wall, and 0 log10 CFU/sponge for samples from air chill room shackles.

(iii) Enumeration and confirmation of Pseudomonas. Pseudomonas was enumerated and confirmed using the Australian Standard method for the detection of Pseudomonas (46) by plating 100 μl of each sample dilution onto a Pseudomonas cephalothin-sodium fusidate-cetrimide selective agar plate (Oxoid) with antibiotics (Oxoid). The enumerated plates were then retained, and five random colonies from each plate were selected for confirmation using oxidase test strips (Sigma-Aldrich, Australia). After confirmation, the recorded Pseudomonas counts were adjusted. The limit of detection of Pseudomonas was 0 log10 CFU/ml for samples in the groups of processing and shelf life, as well as the scald water and immersion chill water in the environmental group. The limits of detection were set at 0 log10 CFU/m3 for the air sample collected by the Coriolis μ biological air sampler from the air chill room, 0 log10 CFU/m2 for samples from the air chill room wall, and 0 log10 CFU/sponge for samples from air chill room shackles.

Bacterial diversity analysis.

(i) DNA extraction. Samples were thawed on ice for 30 min. A QIAamp PowerFecal Pro DNA kit (Qiagen, Victoria, Australia) was used to extract genomic DNA according to the manufacturer’s instructions, which included a mechanical bead-beating step to maximize the yield of genomic DNA. Briefly, a <250-mg pellet for each sample was suspended in 800 μl of Solution CD1 provided in the kit, transferred to the tube containing bead, and incubated in a 65°C water bath for 10 min. The sample was then placed on a MiniBeadBeater-16 (BioSpec, Bartlesville, OK) for two rounds of 30-s homogenization with 30 s of resting in iced water between rounds. The process then followed the manufacturer’s instructions. The concentrations of extracted DNA were measured on a Qubit 2.0 fluorometer (Life Technology, Singapore) using Qubit dsDNA HS assay.

(ii) Library preparation and amplicon sequencing. The extracted DNA was amplified by PCR to construct a library that targeted the V4 region of bacterial 16S rRNA genes as described by Kozich et al. (47) except that Platinum Taq DNA High Fidelity polymerase (Life Technologies, Australia) was used for amplification. After PCR, the amplicons were visualized against a GeneRuler 100-bp Plus DNA ladder (Thermo Fisher, Queensland, Australia) on a 2% (wt/vol) agarose gel stained with ethidium bromide.

The amplicon concentration of each sample was calculated by using GelAnalyzer (version 2010a). Portions (50 ng) of amplicon for each sample with unique dual barcodes were pooled. Then, the pooled barcoded library was purified using Agencourt AMPure XP magnetic beads (Beckman Coulter) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, for which a combination ratio of 0.5/0.7 was chosen to shear the targeted amplicon fragment. The targeted fragment of the pooled library was visualized on a 2% (wt/vol) agarose gel stained with ethidium bromide under UV light pre- and postpurification to ensure the targeted amplicon product was not lost significantly. The purified library was then quantified on a Qubit 2.0 fluorometer using a Qubit dsDNA HS assay kit and a NanoPhotometer (Implen 1289; Implen, United Kingdom). The purified library of 27.4 ng/μl containing samples from 80 chicken carcasses, 12 environmental samples, 8 extraction controls, and 4 PCR controls was sent to the Ramaciotti Centre for Genomics (University of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia) for sequencing using the Illumina MiSeq platform.

(iii) Sequence data analysis. Both demultiplexed R1 and R2 sequencing reads (∼250 bp in length) files were downloaded from the BaseSpace and deposited in the National Center for Biotechnology Information (BioProject accession number PRJNA596532). Sequencing reads were processed using a mothur pipeline (version 1.42.0) following the MiSeq SOP (47). Sequence reads for each sample were rarefied and subsampled to the same level across all samples within the pipeline. The sequence reads were clustered to construct an OTU table with 97% identity. Representative sequences were classified into the respective taxonomical levels from phylum to genus based on the Silva 16S rRNA gene database SSURef_132_SILVA (48).

Statistical analysis.

For the microbiological analysis, all bacterial counts were logarithmically transformed, prior to analyzing the mean with the standard deviations across all sampling points. RStudio version 1.2.1335 was used to perform one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Student t test by the ggsignif version 0.5.0 to compare statistical significance between sampling points. Unless stated otherwise, “*” indicates P < 0.05, “**” indicates P < 0.01, “***” indicates P < 0.001, and “NS” indicates not significant in the figures.

For the multivariate analysis to examine the bacterial diversity across 12 sampling points, a mean value was calculated from all samples to represent the respective sampling point. Past v.4.0 (49) was used to perform ANOVA with the Mann-Whitney pairwise test (50), with the Bonferroni correction (51) to evaluate the statistical significance of changes of chosen phyla and genera between certain sampling steps. The distribution and the relationship of individual samples or sampling steps was analyzed by PCoA based on the Bray-Curtis coefficient. Metric multidimensional scaling (metric MDS) was used to differentiate individual samples. Metric MDS was based on the weighted Spearman rank correlation, which was determined by bootstrapping samples at 95% confidence intervals. All samples or sampling points were standardized by total and transformed by square root prior to conducting PCoA, metric MDS, and heatmap analysis. All multivariate analysis was conducted in PRIMER (v7.0.13; PRIMER-e, Ivybridge, UK).

Data availability.

The sequence data for the study are available in the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) database within the BioProject accession number PRJNA596532.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was funded by the Strategic Innovative Projects program of the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organization (CSIRO; project number R-10150-01).

We thank Glen Mellor and Nirmani Wickramasinghe for technical advice, Kate McMillan for general laboratory consumables, and Seong San Kang and Annaleise Wilson for assistance with sampling at the poultry production plant (all from CSIRO). We also thank the poultry production plant in Australia for participating in the study.

Footnotes

Supplemental material is available online only.

REFERENCES

- 1.ABARES. 2017. Agricultural commodity statistics, 2017. Australian Bureau of Agricultural and Resource Economics, Canberra, Australia: http://data.daff.gov.au/data/warehouse/agcstd9abcc002/agcstd9abcc0022017_IugZg/ACS_2017_v1.1.0.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Batz MB, Hoffmann S, Morris JG Jr. 2012. Ranking the disease burden of 14 pathogens in food sources in the United States using attribution data from outbreak investigations and expert elicitation. J Food Prot 75:1278–1291. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X.JFP-11-418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.WHO. 2015. WHO estimates of the global burden of foodborne diseases In Foodborne disease burden epidemiology reference group, 2007–2015. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marder EP, Cieslak PR, Cronquist AB, Dunn J, Lathrop S, Rabatsky-Ehr T, Ryan P, Smith K, Tobin-D’Angelo M, Vugia DJ, Zansky S, Holt KG, Wolpert BJ, Lynch M, Tauxe R, Geissler AL. 2017. Incidence and trends of infections with pathogens transmitted commonly through food and the effect of increasing use of culture-independent diagnostic tests on surveillance: Foodborne Diseases Active Surveillance Network, 10 U.S. sites, 2013–2016. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.EFSA/ECDC. 2019. Scientific report on the European Union One Health 2018 Zoonoses Report. 10.2903/j.efsa.2019.5926. European Food Safety Authority, Parma, Italy. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.NNDSS. 2020. National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System of all diseases by state and territory and year. The Department of Health, Melbourne, Australia: http://www9.health.gov.au/cda/source/rpt_2.cfm. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Belluco S, Barco L, Roccato A, Ricci A. 2016. Escherichia coli and Enterobacteriaceae counts on poultry carcasses along the slaughterline: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Food Control 60:269–280. doi: 10.1016/j.foodcont.2015.07.033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen SH, Fegan N, Kocharunchitt C, Bowman JP, Duffy LL. 2020. Changes of the bacterial community diversity on chicken carcasses through an Australian poultry processing line. Food Microbiol 86:103350. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2019.103350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang H, Qin X, Mi S, Li X, Wang X, Yan W, Zhang C. 2019. Contamination of yellow-feathered broiler carcasses: microbial diversity and succession during processing. Food Microbiol 83:18–26. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2019.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.ICMSF. 2005. Microorganisms in foods—6: microbial ecology of food commodities, 2nd ed. Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Handley JA, Park SH, Kim SA, Ricke SC. 2018. Microbiome profiles of commercial broilers through evisceration and immersion chilling during poultry slaughter and the identification of potential indicator microorganisms. Front Microbiol 9:345. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.00345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim SA, Park SH, Lee SI, Owens CM, Ricke SC. 2017. Assessment of chicken carcass microbiome responses during processing in the presence of commercial antimicrobials using a next generation sequencing approach. Sci Rep 7:43354. doi: 10.1038/srep43354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rothrock MJ Jr, Locatelli A, Glenn TC, Thomas JC, Caudill AC, Kiepper BH, Hiett KL. 2016. Assessing the microbiomes of scalder and chiller tank waters throughout a typical commercial poultry processing day. Poult Sci 95:2372–2382. doi: 10.3382/ps/pew234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wages JA, Feye KM, Park SH, Kim SA, Ricke SC. 2019. Comparison of 16S rDNA next sequencing of microbiome communities from post-scalder and post-picker stages in three different commercial poultry plants processing three classes of broilers. Front Microbiol 10:972. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.00972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goksoy EO, Kirkan S, Kok F. 2004. Microbiological quality of broiler carcasses during processing in two slaughterhouses in Turkey. Poult Sci 83:1427–1432. doi: 10.1093/ps/83.8.1427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Friedman CR, Neimann J, Wegener HC, Tauxe RV. 2000. Epidemiology of Campylobacter jejuni infections in the United States and other industrialized nations, p 121–138. In Nachamkin I, Blaser MJ (ed), Campylobacter, 2nd ed. ASM Press, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Keener KM, Bashor MP, Curtis PA, Sheldon BW, Kathariou S. 2004. Comprehensive review of Campylobacter and poultry processing. Comp Rev Food Sci Food Safety 3:105–116. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-4337.2004.tb00060.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guerin MT, Sir C, Sargeant JM, Waddell L, O’Connor AM, Wills RW, Bailey RH, Byrd JA. 2010. The change in prevalence of Campylobacter on chicken carcasses during processing: a systematic review. Poult Sci 89:1070–1084. doi: 10.3382/ps.2009-00213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cho TJ, Rhee MS. 2019. Underrecognized niche of spore-forming bacilli as a nitrite-producer isolated from the processing lines and end-products of powdered infant formula. Food Microbiol 80:50–61. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2018.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Karaca B, Buzrul S, Coleri Cihan A. 2019. Anoxybacillus and Geobacillus biofilms in the dairy industry: effects of surface material, incubation temperature and milk type. Biofouling 35:551–560. doi: 10.1080/08927014.2019.1628221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.André S, Vallaeys T, Planchon S. 2017. Spore-forming bacteria responsible for food spoilage. Res Microbiol 168:379–387. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2016.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Khan IU, Habib N, Xiao M, Devi AM, Habib M, Hejazi MS, Salam N, Zhi X-Y, Li W-J. 2018. Anoxybacillus sediminis sp. nov., a novel moderately thermophilic bacterium isolated from a hot spring. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 111:2275–2282. doi: 10.1007/s10482-018-1118-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Burgess SA, Brooks JD, Rakonjac J, Walker KM, Flint SH. 2009. The formation of spores in biofilms of Anoxybacillus flavithermus. J Appl Microbiol 107:1012–1018. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2009.04282.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fernández H, Vergara M, Tapia F. 1985. Dessication resistance in thermotolerant Campylobacter species. Infection 13:197. doi: 10.1007/bf01642813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Escudero-Gilete ML, González-Miret ML, Heredia FJ. 2005. Multivariate study of the decontamination process as function of time, pressure and quantity of water used in washing stage after evisceration in poultry meat production. J Food Eng 69:245–251. doi: 10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2004.08.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maes S, Vackier T, Nguyen Huu S, Heyndrickx M, Steenackers H, Sampers I, Raes K, Verplaetse A, De Reu K. 2019. Occurrence and characterization of biofilms in drinking water systems of broiler houses. BMC Microbiol 19:77–77. doi: 10.1186/s12866-019-1451-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bifulco JM, Shirey JJ, Bissonnette GK. 1989. Detection of Acinetobacter spp. in rural drinking water supplies. Appl Environ Microbiol 55:2214–2219. doi: 10.1128/AEM.55.9.2214-2219.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Duffy LL, Blackall PJ, Cobbold RN, Fegan N. 2014. Quantitative effects of in-line operations on Campylobacter and Escherichia coli through two Australian broiler processing plants. Int J Food Microbiol 188:128–134. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2014.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rothrock MJ Jr, Hiett KL, Kiepper BH, Ingram K, Hinton A. 2013. Quantification of zoonotic bacterial pathogens within commercial poultry processing water samples using droplet digital PCR. Adv Microbiol 3:403–411. doi: 10.4236/aim.2013.35055. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Finstad S, O’Bryan CA, Marcy JA, Crandall PG, Ricke SC. 2012. Salmonella and broiler processing in the United States: relationship to foodborne salmonellosis. Food Res Int 45:789–794. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2011.03.057. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stopforth JD, O’Connor R, Lopes M, Kottapalli B, Hill WE, Samadpour M. 2007. Validation of individual and multiple-sequential interventions for reduction of microbial populations during processing of poultry carcasses and parts. J Food Prot 70:1393–1401. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X-70.6.1393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Suphoronski SA, Chideroli RT, Facimoto CT, Mainardi RM, Souza FP, Lopera-Barrero NM, Jesus GFA, Martins ML, Di Santis GW, de Oliveira A, Gonçalves GS, Dari R, Frouel S, Pereira UP. 2019. Effects of a phytogenic, alone and associated with potassium diformate, on tilapia growth, immunity, gut microbiome and resistance against francisellosis. Sci Rep 9:1–14. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-42480-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yutin N, Galperin MY. 2013. A genomic update on clostridial phylogeny: Gram-negative spore formers and other misplaced clostridia. Environ Microbiol 15:2631–2641. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.12173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gerritsen J, Hornung B, Renckens B, van Hijum SAFT, Martins dos Santos VAP, Rijkers GT, Schaap PJ, de Vos WM, Smidt H. 2017. Genomic and functional analysis of Romboutsia ilealis CRIBT reveals adaptation to the small intestine. PeerJ Life Environ 5:e3698. doi: 10.7717/peerj.3698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jurburg SD, Brouwer MSM, Ceccarelli D, van der Goot J, Jansman AJM, Bossers A. 2019. Patterns of community assembly in the developing chicken microbiome reveal rapid primary succession. MicrobiologyOpen 8:e00821. doi: 10.1002/mbo3.821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xin J, Chai Z, Zhang C, Zhang Q, Zhu Y, Cao H, Zhong J, Ji Q. 2019. Comparing the microbial community in four stomach of dairy cattle, yellow cattle and three yak herds in Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau. Front Microbiol 10:1547. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.01547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li Z, Wang X, Zhang T, Si H, Nan W, Xu C, Guan L, Wright A-D, Li G. 2018. The development of microbiota and metabolome in small intestine of sika deer (Cervus nippon) from birth to weaning. Front Microbiol 9:4. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Antony R, Sanyal A, Kapse N, Dhakephalkar PK, Thamban M, Nair S. 2016. Microbial communities associated with Antarctic snow pack and their biogeochemical implications. Microbiol Res 192:192–202. doi: 10.1016/j.micres.2016.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Králová S, Busse H-J, Švec P, Mašlaňová I, Staňková E, Barták M, Sedláček I. 2019. Flavobacterium circumlabens sp. nov. and Flavobacterium cupreum sp. nov., two psychrotrophic species isolated from Antarctic environmental samples. Syst Appl Microbiol 42:291–301. doi: 10.1016/j.syapm.2018.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Maes S, Heyndrickx M, Vackier T, Steenackers H, Verplaetse A, De Reu K. 2019. Identification and spoilage potential of the remaining dominant microbiota on food contact surfaces after cleaning and disinfection in different food industries. J Food Prot 82:262–275. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X.JFP-18-226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mageswari A, Subramanian P, Srinivasan R, Karthikeyan S, Gothandam KM. 2015. Astaxanthin from psychrotrophic Sphingomonas faeni exhibits antagonism against food-spoilage bacteria at low temperatures. Microbiol Res 179:38–44. doi: 10.1016/j.micres.2015.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Møretrø T, Langsrud S. 2017. Residential bacteria on surfaces in the food industry and their implications for food safety and quality. Comp Rev Food Sci Food Safety 16:1022–1041. doi: 10.1111/1541-4337.12283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yuan L, Sadiq FA, Burmolle M, Wang N, He G. 2019. Insights into psychrotrophic bacteria in raw milk: a review. J Food Prot 82:1148–1159. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X.JFP-19-032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Samapundo S, de Baenst I, Aerts M, Cnockaert M, Devlieghere F, Van Damme P. 2019. Tracking the sources of psychrotrophic bacteria contaminating chicken cuts during processing. Food Microbiol 81:40–50. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2018.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Khan IUH, Gannon V, Loughborough A, Jokinen C, Kent R, Koning W, Lapen DR, Medeiros D, Miller J, Neumann N, Phillips R, Robertson W, Schreier H, Topp E, van Bochove E, Edge TA. 2009. A methods comparison for the isolation and detection of thermophilic Campylobacter in agricultural watersheds. J Microbiol Methods 79:307–313. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2009.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Standards Australia. 2017. Australian standard—food microbiology. Meat and meat products, part 21: enumeration of presumptive Pseudomonas spp. AS 5013.21:2017. Standards Australia, Sydney, Australia. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kozich JJ, Westcott SL, Baxter NT, Highlander SK, Schloss PD. 2013. Development of a dual-index sequencing strategy and curation pipeline for analyzing amplicon sequence data on the MiSeq Illumina sequencing platform. Appl Environ Microbiol 79:5112–5120. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01043-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Quast C, Pruesse E, Yilmaz P, Gerken J, Schweer T, Yarza P, Peplies J, Glöckner FO. 2013. The SILVA ribosomal RNA gene database project: improved data processing and web-based tools. Nucleic Acids Res 41:D590–D596. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hammer Ø, Harper DAT, Ryan PD. 2001. Past: paleontological statistics software package for education and data analysis. Palaeontologia Electronica 4:19–20. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mann HB, Whitney DR. 1947. On a test of whether one of two random variables is stochastically larger than the other. Ann Math Statist 18:50–60. doi: 10.1214/aoms/1177730491. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dunn OJ. 1961. Multiple comparisons among means. J Am Stat Assoc 56:52–64. doi: 10.1080/01621459.1961.10482090. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The sequence data for the study are available in the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) database within the BioProject accession number PRJNA596532.