To the Editor,

The coronavirus COVID‐19 pandemic, which emerged in Wuhan, China several months ago, 1 has led to large‐scale lockdown in many countries around the world, including Spain. Uncertainty about the duration of these measures led us to consider the potential impact of diagnostic delays due to the paralysation of certain health procedures and services on the prognosis of patients with melanoma.

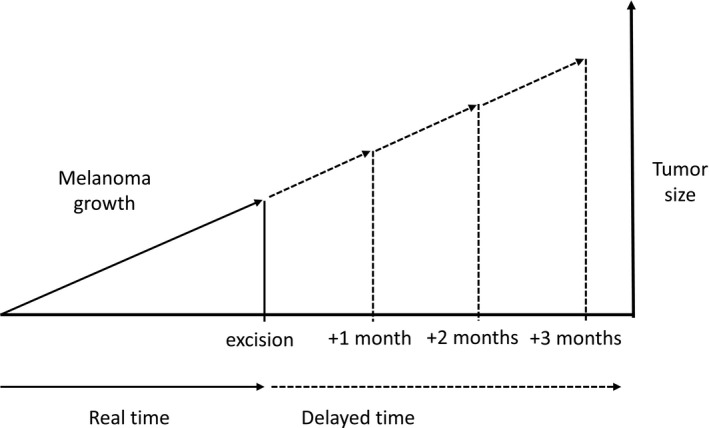

To estimate this impact, we built a model based on melanoma rate of growth (ROG). 2 ROG is the rate of increase in Breslow thickness, as a surrogate measure for tumour volume, from the time a patient first notices a lesion or observes changes in an existing lesion, to excision of the tumour. It is measured as millimetres per month (Fig. 1). Although ROG in our model was based on subjective information provided by the patient, it has been found to match ROG values calculated using biopsy specimens taken from the same lesions at different moments of time. 3 Melanoma ROG has been associated with prognosis 4 , 5 and a higher probability of lymph node involvement. 6

Figure 1.

Theoretical basis of model. Growth rate over time to estimate tumour thickness in successive months.

We randomly selected 1000 melanomas with a known ROG from the database of Instituto Valenciano de Oncología in Valencia, Spain. The tumours were classified according to thickness (T1, T2, T3 or T4) based on the melanoma staging criteria of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC). 7 For each case, we used ROG to estimate tumour thickness after a diagnostic delay of 1, 2 and 3 months. We calculated, e.g., that a melanoma with a Breslow thickness of 2 mm at diagnosis and a ROG of 0.5 mm a month would measure 2.5 mm after 1 month, 3 mm after 2 months and 3.5 mm after 3 months. Using AJCC survival data for the different T stages, 7 we then calculated 5‐ and 10‐year survival rates for the patients divided into diagnostic groups (initial sample and the same group at the three time points analysed).

Over half of the melanomas in the initial sample (n = 403; 40.3%) were T1. Of the remaining tumours, 24.2% were T2, 19.2% were T3, and 16.3% were T4. For patients in the 1‐month diagnostic delay group, the model predicted an upstaging rate of 21% (i.e. progression to the next tumour stage in 21% of cases). The proportion of tumours that would be upstaged in the other two groups was 29% in the 2‐month‐delay group and 45% in the 3‐month‐delay group (Table 1). After 3 months, thus, there were 275 (27.5%) stage T1 tumours (vs. 40.3% in the initial sample) and 304 (30.4%) stage T4 tumours (vs. 16.3% in the initial sample).

Table 1.

Tumour thickness at diagnosis and estimated thickness after 1, 2 and 3 months of diagnostic delay based on rate of growth calculations (mm/month) for 1000 randomly selected melanomas from the database of the Instituto Valenciano de Oncología

| Thickness | Study group | 1‐month diagnostic delay | 2‐month diagnostic delay | 3‐month diagnostic delay |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1 ( ≤1 mm) | 403 (40.3%) | 339 (33.9%) | 304 (30.4%) | 275 (27.5%) |

| T2 (1.1–2.0 mm) | 242 (24.2%) | 227 (22.7%) | 217 (21.7%) | 219 (21.9%) |

| T3 (2.1–4 mm) | 192 (19.2%) | 202 (20.2%) | 203 (20.3%) | 202 (20.2%) |

| T4 (>4 mm) | 163 (16.3%) | 232 (23.2%) | 276 (27.6%) | 304 (30.4%) |

| Estimated 5‐year survival † (%) | 94.2 | 93.2 | 92.7 | 92.3 |

| Estimated 10‐year survival † (%) | 90 | 88.8 | 88.1 | 87.6 |

Based on American Joint Committee on Cancer survival data for T1–T4 melanomas.

Estimated 5‐year survival for the group as a whole was 94.2% in the initial sample and 92.3% in the group of patients whose diagnosis was delayed by 3 months. The respective 10‐year survival rates were 90% and 87.6%.

One limitation of our study is that the random sample included 1000 cases, although the distribution of tumour thickness measurements was very similar to that in the Spanish National Melanoma Registry. 8 We did not estimate clinical progression rates, as it was impossible to estimate the proportion of non‐ulcerated tumours that would become ulcerated in the time periods considered. The actual differences in survival rates could thus be even greater.

Our ROG model shows that in the absence of adequate care for cancer patients in the current lockdown situation in Spain, our healthcare system could see a considerable rise in melanoma upstaging cases, and, of course, healthcare costs. 9

Approximately 300 patients are diagnosed of cutaneous melanoma every month in Spain, 10 and if we extrapolate this figure to countries with similar lockdown measures, many of which have a higher incidence of melanoma, it would not be unrealistic to predict a situation with potentially serious consequences. In conclusion, considering the current situation, efforts should be made to promote self‐examination and facilitate controlled access to dermatologists (through teledermatology, e.g.), as this will prevent delays resulting in worse prognosis.

References

- 1. Phelan AL, Katz R, Gostin LO. The novel coronavirus originating in Wuhan, China: challenges for Global Health Governance. J Am Med Assoc 2020; 323: 709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Grob JJ, Richard MA, Gouvernet J et al. The kinetics of the visible growth of a primary melanoma reflects the tumor aggressiveness and is an independent prognostic marker: a prospective study. Int J Cancer 2002; 102: 34–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lin MJ, Mar V, McLean C, Kelly JW. An objective measure of growth rate using partial biopsy specimens of melanomas that were initially misdiagnosed. J Am Acad Dermatol 2014; 71: 691–697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Tejera‐Vaquerizo A, Barrera‐Vigo MV, López‐Navarro N, Herrera‐Ceballos E. Growth rate as a prognostic factor in localized invasive cutaneous melanoma. J Eur Acad Dermatology Venereol 2010; 24: 147–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Nagore E, Martorell‐Calatayud A, Botella‐Estrada R, Guillén C. Growth rate as an independent prognostic factor in localized invasive cutaneous melanoma. J Eur Acad Dermatology Venereol 2011; 25: 618–620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Tejera‐Vaquerizo A, Nagore E, Herrera‐Acosta E et al. Prediction of sentinel lymph node positivity by growth rate of cutaneous melanoma. Arch Dermatol 2012; 148: 1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gershenwald JE, Scolyer RA, Hess KR et al. Melanoma staging: Evidence‐based changes in the American Joint Committee on Cancer eighth edition cancer staging manual. CA Cancer J Clin 2017; 67: 472–492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Rios L, Nagore E, Lopez JL et al. The spanish national cutaneous melanoma registry. Tumour characteristics at diagnosis: 15 years of experience. [Spanish] Registro nacional de melanoma cutaneo. Caracteristicas del tumor en el momento del diagnostico: 15 anos de experiencia. Actas Dermosifiliogr 2013; 104: 789–799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Serra‐Arbeloa P, Rabines Juárez ÁO, Álvarez‐Ruiz MS, Guillen‐Grima F. Estudio descriptivo de costes en melanoma cutáneo de diferentes estadios. Actas Dermosifiliogr 2017; 108: 229–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Tejera‐Vaquerizo A, Descalzo‐Gallego MA, Otero‐Rivas MM et al. Incidencia y mortalidad del cáncer cutáneo en España: revisión sistemática y metaanálisis. Actas Dermosifiliogr 2016; 107: 318–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]