Abstract

Cases of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) emigrating from Wuhan escalated the risk of spreading the disease in other cities. This report focused on outside‐Wuhan patients to assess the transmission and clinical characteristics of this illness. Contact investigation was conducted on each patient who was admitted to the assigned hospitals in Hunan Province (geographically adjacent to Wuhan) from 22 January to 23 February 2020. Cases were confirmed by the polymerase chain reaction test. Demographic, clinical, and outcomes were collected and analyzed. Of the 104 patients, 48 (46.15%) were cases who immigrated from Wuhan; 93 (89.42%) had a definite contact history with infection. Family clusters were the major body of patients. Transmission along the chain of three “generations” was observed. Five asymptomatic infected cases were found and two of them infected their relatives. Mean age was 43 (range, 8‐84) years, and 49 (47.12%) were male. The median incubation period was 6 (range, 1‐32) days, which of 8 patients ranged from 18 to 32 days, 96 (92.31%) were discharged, and 1 (0.96%) died. The average hospital stay was 10 (range, 8‐14) days. Family but not community transmission became the main body of infections in the two centers, suggesting the timely control measures after the Wuhan shutdown worked well. Asymptomatic transmission demonstrated here warned us that it may lead to the widespread of COVID‐19. A 14‐day quarantine may need to be prolonged.

Keywords: asymptomatic transmission, coronavirus disease 2019, transmission and clinical characteristics

Highlights

The smoothly increase in the cumulative number of confirmations of the two centers indicates that the timely control measures work well, family clusters represent as the major body of infections, transmission along the chain of 3 “generations” was observed. No gender difference of patients was found, indicating male and female may have the same susceptibility of this illness. But the asymptomatic transmission demonstrated here warned us it may bring more risk to the spread of COVID‐19. The differences in demographics and clinical characteristics between emigrated patients and indigenous cases were not significant.

1. INTRODUCTION

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19), which is caused by SARS‐CoV‐2, was officially named by the World Health Organization (WHO) on 11 February 2020. Till 22 April 2020, COVID‐19 infected more than 2584 545 people worldwide. 1 Evidence demonstrated the person‐to‐person transmission of COVID‐19. 2 , 3 , 4 The sharp increase in infections and the medical shortage in Wuhan may be the major reason behind the outbreak of COVID‐19 in the early stage. On 23 January 2020 before the Chinese Lunar New Year, a precedent scale of Wuhan Shutdown was implemented to block or slow the spread of COVID‐19.

Unlike the initial infections which all closely related to the Huanan seafood market in Wuhan, China, infections in other cities were mainly linked to the patients emigrated from Wuhan. 5 It is worth noting that the epidemic and clinical status of people from outside Wuhan may largely differ from those in Wuhan. Serval studies have shown the high ICU rates and hospital‐associated infections in Wuhan. 2 , 6 With limited information about COVID‐19, it is also hard to assess how bad this novel coronavirus is going to get.

Hunan Province is geographically adjacent to Wuhan, Hubei Province; high‐efficiency transport between the two provinces may have led to a rapid spread of COVID‐19 in Hunan Province. This report included 104 patients of two hospitals in Hunan Province to assess the transmission and clinical characteristics of COVID‐19 in China. These findings could provide valuable information to better understand such disease.

2. METHODS

2.1. Study population

In this study, we recruited confirmed patients with COVID‐19 from two hospitals, the First People's Hospital of Huaihua and the Central Hospital of Shaoyang which is designated as the treatment center of Huaihua and Shaoyang city, Huanan Province, China from 22 January to 12 February 2020, the follow‐up lasted to 23 February 2020. According to the guidelines of China, 7 patients were confirmed by the positive result from the real‐time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT‐PCR) assay of nasopharyngeal or throat swab. Suspected infectors who were not confirmed by PCR were excluded. For the study population, the cases who emigrated from Wuhan were defined as an infector (who ever lived in or traveled to Wuhan) and the rest of the study patients were defined as indigenous cases.

2.2. Procedures

We carefully surveyed the contact history of every patient, including whether he or she ever lived in or traveled to Wuhan, or had closely contacted people returning from Wuhan during 2 months before the onset of their illness. In addition, the history of contact with animals and eating game meat was also screened. If necessary, we directly communicated with the attending physician, patients, or their family members. Demographic, clinical characteristics, underlying comorbidities, symptoms, sign, and chest computed tomographic images were obtained from electronic medical records. Outcomes were followed till 23 February 2020. Standard questionnaires and forms were used for contact investigation and data collection. The data were independently reviewed by two trained physicians (Ye Deng and Xin Liao) and checked by another two physicians (Hongqiang Wang and Da Long). Everyone signed Data Authenticity Commitment and stamp official seal. The date of onset symptom was defined as the day when the case first developed symptoms related to COVID‐19. Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), acute kidney injury, liver function abnormal, and cardiac injury were defined according to the guidelines. 2 , 8 , 9

2.3. Real‐time RT‐PCR assay

In this study, case confirmation accords to the positive results of PCR. Nasopharyngeal swab was collected from suspected patients. Sample collection and extraction followed the standard procedure. The primers and probe‐target to open reading frame (ORF1ab) and nucleoprotein (N) gene of COVID‐19 were used. The procedure and reaction condition for PCR application was followed by the manufacture's protocol (Sansure Biotech). Results definition accords to the recommendation by the National Institute for Viral Disease Control and Prevention (China). 10

2.4. Ethics approval

This study was approved by the ethics committee of the First People's Hospital of Huaihua (KY‐2020013101) and the Central Hospital of Shaoyang (KY‐202000103), China. Considering the infection of COVID‐19, we took oral informed consent with every patient instead of written informed consent (www.chictr.org.cn, Chi CTR2000029734).

2.5. Statistical analysis

Normally distributed continuous variables were described as mean and standard deviation (SD). For nonnormally distributed continuous variables, we used median and interquartile range (IQR) or range. Categorical variables were expressed as ratio and percentages (%). Differences in means of normally distributed continuous variables were compared using the Student t test (two groups) and the nonnormally distributed continuous variables compared using the Mann‐Whitney U test. Categorical variables were compared using the χ 2 test or Fisher exact test. A two‐sided P value of .05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical tests were performed using SPSS version 25.0.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Control measures in China and current status in two centers

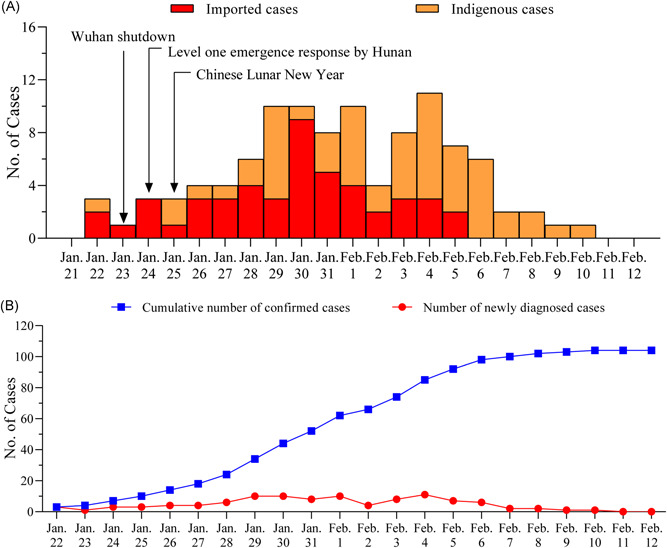

With the sharp increase in the number of COVID‐19 cases in Wuhan in January 2020, China ordered the shutdown of Wuhan city on 23 January 2020. Hunan Province, geographically close to Wuhan, immediately launched a level‐one emergency response to prevent the spread. From 22 January to 12 February 2020, 104 cases were confirmed in the two centers of Hunan Province, 48 (46.15%) were emigrated cases, and 56 (53.85%) were indigenous cases. Since 6 February 2020, emigrated cases were no longer reported in the two centers (Figure 1A). The cumulative number of confirmed cases increased smoothly in the two centers (Figure 1B), a slight increase of newly confirmed cases was observed from 22 January 2020 to 4 February 2020, and then the number started to decline and the trend lasted to 12 February 2020 (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Timeline of control measures in China and current status in two centers. A, The timeline of control measures in China and the time distribution of emigrated cases and indigenous cases. B, The growth of cumulative confirmed patients and the newly confirmed cases per day

3.2. Transmission characteristics of 104 patients

With the aim to better understand the transmission characteristics of COVID‐19 in outside Wuhan cities, we carefully evaluated the contact history of each patient. Of the 104 patients, 93 (89.42%) patients had a clear contact history with the infection and 11 (10.53%) were sporadic cases that hardly identified a definite contact history. As shown in Table 1, cluster infections including couples, relatives, friends, and colleagues transmitted mainly through close contact by domestic life or dinner. Family clusters accounted for the most infections of COVID‐19 in this study population. Clusters 6 (2 cases) and 14 (7 cases) got infected via taking the same public vehicle together. Nosocomial transmission did not happen so far in the two centers. Six clusters (Table 1, clusters 2, 12, 14, 15, 18, and 19) demonstrated the existence of transmission chain of three “generation” (index case of one cluster identified as an infector who originally contracted the COVID‐19 from Wuhan and then infected someone else, who infected another individual). Of note, five asymptomatic cases (C'1, C'2, C'3, C'4, and C102) were found in this study. In cluster 5, C89 was infected by his wife C45. With the aim to fast screen the potential infections, their family members took the PCR test. Their son‐in‐law (C'1) and their grandson (C'2) (C'1 and C'2 not included in this study population) got positive results in another hospital, but till now all of them had never developed any symptoms. In cluster 17, C'3 (not included in this study population) returned Shaoyang city from Wuhan on 19 January 2020, three relatives of C'3 were identified with COVID‐19 infection after several days of close contact with C'3. None of them came in contact with other suspected infectors during those days. Her sister‐in‐law (C37) was confirmed on 1 February 2020 and her sister (C44) and mother (C49) were confirmed on 4 February 2020. But so far, C'3 never developed any symptoms. Whether C'3 had asymptomatic infection was not been identified by the PCR test, but the same contact history and the similar onset time of her three relatives indicated that C'3 was an asymptomatic COVID‐19‐carrier. In cluster 19, C'4 (not included in this study population) got in contact with her colleague who traveled from Wuhan, and soon confirmed by PCR positive result. As an asymptomatic patient, C'4 infected C92 (C'4's mother), C94 (C'4's father‐in‐law), and C102 (C'4's daughter), C102 also had no symptoms with a positive result of PCR test.

Table 1.

Transmission characteristics of 104 patients

| Subgroups | No. of case | Index cases | Transmission route | The second generation | Transmission route | The third generation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cluster 1 | 2 | C5 | Domestic life | C10 (son) | ||

| C11 (colleague) | C34 (friend) | C86 (sister) | ||||

| Cluster 2 | 8 | C12 (colleague) | Domestic life | C87 (friend) | Domestic life or dinner | C95 (husband) |

| X1 (colleague) | C98 (friend) | X2 (nephew) | ||||

| C100 (brother) | ||||||

| Cluster 3 | 2 | C18 | Domestic life | C7 (wife) | ||

| Cluster 4 | 3 | C28 | Domestic life | C26 (daughter) | ||

| C85 (husband) | ||||||

| C89 (husband) | ||||||

| Cluster 5 | 2 | C45 | Domestic life | C’1 (son‐in‐law) | ||

| C’2 (grandson) | ||||||

| Cluster 6 | 2 | C47 | Public vehicle | C91 (uncle) | ||

| Cluster 7 | 2 | C57 | Domestic life | C78 (son) | ||

| Cluster 8 | 2 | C61 | Domestic life | C73 (friend) | ||

| Cluster 9 | 2 | C68 | Domestic life | C66 (wife) | ||

| Cluster 10 | 4 | C70 | Domestic life | C74 (sister) | ||

| C76 (father) | ||||||

| C81 (mother) | ||||||

| Cluster 11 | 2 | C77 | Domestic life | C75 (wife) | ||

| Cluster 12 | 5 | C79 (colleague) | Domestic life | C59 (colleague) | ||

| C55 (colleague) | C60 (colleague) | Dinner | C103 (mother) | |||

| Cluster 13 | 2 | C80 | Domestic life | C82 (husband) | ||

| Cluster 14 | C6 (passenger) | |||||

| C35 (passenger) | ||||||

| 8 | C90 (colleague) | Public vehicle | C36 (passenger) | |||

| X3 (colleague) | C42 (passenger) | Dinner | C88 (sister) | |||

| C43 (passenger) | ||||||

| C97 (passenger) | ||||||

| C17 (sister‐in‐law) | ||||||

| Cluster 15 | 4 | X4 | Dinner | C39 (aunt) | Domestic life | C52 (son) |

| C40 (father) | ||||||

| Cluster 16 | 2 | X5 | Domestic life | C31 (husband) | ||

| C32 (grandma) | ||||||

| C37 (sister‐in‐law) | ||||||

| Cluster 17 | 3 | C’3 | Domestic life | C44 (sister) | ||

| C49 (mother) | ||||||

| Cluster 18 | 2 | X6 | Dinner | C51 (friend) | Domestic life | C96 (daughter) |

| C92 (mother) | ||||||

| Cluster 19 | 3 | X7 | Work | C’4 (colleague) | Domestic life | C94 (father‐in‐law) |

| C102 (daughter) | ||||||

| Cluster 20 | 2 | C14 | Domestic life | C16 (wife) | ||

| Cluster 21 | 2 | C19 | Domestic life | C41 (wife) | ||

| Cluster 22 | 2 | C21 | Domestic life | C22 (husband) | ||

| Cluster 23 | 2 | C23 | ||||

| C25 | ||||||

| Cluster 24 | 2 | X8 | Domestic life | C65 (son) | ||

| C69 (brother) | ||||||

| The others a | 23 | C1, C2, C3, C4, C8, C9, C15, C20, C24, C27, C29, C30, C33, C38, C46, C50, C62, C63, C64, C67, C71, C84, C99 | ||||

| Sporadic cases | 11 | C13, C48, C53, C54, C56, C58, C72, C83, C93, C101, C104 | ||||

Note: C indicates the cases who were confirmed as COVID‐19 pneumonia in the two centers. X indicates the cases who were not included in this study population but were confirmed as COVID‐19 pneumonia or as virus carrier. C’ indicates asymptomatic infections.

The others include the confirmed cases returning from Wuhan but did not infect others. Sporadic cases include indigenous patients who did not identified the source of infection.

3.3. Demographic and clinical characteristics of 104 patients

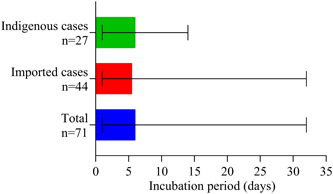

The median incubation duration was 6 days, ranged from 1 to 32 days; eight patients reported more longer incubation duration (18, 19, 20, 21, 23, 24, 24, and 32 days) which is more than 14 days. Median time from onset to confirmation was 6 (range, 0‐17) days (Figure 2). As shown in Table 2, of the 104 patients, 49 (47.12%) were male, the mean age was 43 (range, 8‐83) years, three were children with COVID‐19 aged 13, 8, and 8 years. There were 22 (21.15%) patients who had one or more comorbidities on admission. Common onset symptoms included dry cough (79 [75.96%]), fever (66 [63.46%]), expectoration (39 [37.50%]), fatigue (33 [31.73%]), muscular soreness (20 [19.23%]), and dyspnea (15 [14.42%]). There were 16 (15.38%) patients who were identified as severe, the ratio of male to female was 11:5, and the median age was 53 years (range, 18‐81); nine (8.65%) patients were given ICU care. Some patients were presented with organ function damage, including five (4.81%) with abnormal liver function, three (2.14%) with cardiac injury, and two (1.89%) with acute kidney injury. ARDS occurred in 13 (12.50%) patients. The median time from admission to developed ARDS was 2 (1‐8) days.

Figure 2.

Incubation period of confirmed cases. Date presented as median (range)

Table 2.

Demographics and clinical characteristics of patients infected with COVID‐19

| No. (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Total (N = 104) | Emigrated cases (n = 48) | Indigenous cases (n = 56) | P |

| Male | 49 (47.12) | 22 (45.83) | 27 (48.21) | .81 |

| Age, a y | 43 ± 7.54 | 40 ± 10.67 | 44 ± 19.76 | .15 |

| Age subgroups, y | .001 | |||

| 0‐14 y | 3 (2.89) | 1 (2.08) | 2 (3.57) | |

| 15‐29 y | 20 (19.23) | 6 (12.50) | 14 (25.00) | |

| 30‐44 y | 39 (37.50) | 25 (52.08) | 14 (25.00) | |

| 45‐59 y | 28 (26.92) | 15 (31.25) | 13 (23.21) | |

| ≥60 y | 14 (13.46) | 1 (2.08) | 13 (23.21) | |

| Smoke | 4 (3.85) | 1 (2.08) | 3 (5.36) | .72 |

| Drink | 2 (1.92) | 1 (2.08) | 1 (1.79) | >.99 |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Diabetes | 12 (11.54) | 7 (14.58) | 5 (8.93) | .37 |

| Hypertension | 15 (14.42) | 6 (12.50) | 9 (16.07) | .61 |

| Cardiovascular disease | 7 (6.73) | 1 (2.08) | 6 (10.71) | .17 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 1 (0.96) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.79) | >.99 |

| Onset symptoms | ||||

| Dry cough | 79 (75.96) | 36 (75.00) | 43 (76.79) | .83 |

| Fever | 66 (63.46) | 36 (75.00) | 30 (53.57) | .02 |

| Expectoration | 39 (37.50) | 14 (29.17) | 25 (44.64) | .10 |

| Fatigue | 33 (31.73) | 16 (33.33) | 17 (30.36) | .75 |

| Muscular soreness | 20 (19.23) | 13 (27.08) | 7 (12.50) | .06 |

| Dyspnea | 15 (14.42) | 9 (18.75) | 6 (10.71) | .24 |

| Running nose | 2 (1.92) | 0 (0) | 2 (3.57) | .50 |

| Sneeze | 1 (0.96) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.79) | >.99 |

| Pharyngula | 6 (5.77) | 3 (6.25) | 3 (5.36) | >.99 |

| Encephalalgia | 5 (4.81) | 4 (8.33) | 1 (1.79) | .27 |

| Hemoptysis | 1 (0.96) | 1 (2.08) | 0 (0) | .46 |

| Diarrhea | 2 (1.92) | 0 (0) | 2 (3.57) | .50 |

| Palpitation | 1 (0.96) | 1 (2.08) | 0 (0) | .46 |

| Others d | 7 (6.73) | 4 (8.33) | 3 (5.36) | .83 |

| Incubation period, b , c , d | 6 (1‐32) | 5.5 (1‐32) | 6 (1‐14) | .71 |

| Time from onset to diagnosis, b, , d | 6 (0‐17) | 6 (1‐14) | 6 (0‐17) | .74 |

| Severe cases | 16 (15.38) | 8 (16.67) | 8 (14.28) | .74 |

| Intensive care unit | 9 (8.65) | 3 (6.25) | 6 (10.71) | .65 |

| Hospital stays of discharged cases, b, , d | 10 (8‐14) | 10 (9‐13) | 10 (7‐16) | .62 |

| Complications | ||||

| Acute respiratory distress syndrome | 12 (11.54) | 5 (10.42) | 7 (12.50) | .74 |

| Acute kidney injury | 2 (1.92) | 0 (0) | 2 (3.57) | .50 |

| Liver function abnormal | 5 (4.81) | 3 (6.25) | 2 (3.57) | .86 |

| Cardiac injury | 3 (2.14) | 0 (0) | 3 (5.36) | .30 |

| Bacterial infection | 15 (14.42) | 7 (14.58) | 8 (14.28) | .97 |

| Shock | 2 (1.92) | 0 (0) | 2 (3.57) | >.99 |

| Laboratory parameters | ||||

| White blood cell count, b ×109/L (n = 101) | 5.04 (4.13‐7.06) | 4.99 (4.16‐5.94) | 5.14 (4.09‐7.50) | .50 |

| Lymphocyte count, b ×109/L (n = 101) | 0.97 (0.71‐1.47) | 0.85 (0.66‐1.09) | 1.08 (0.76‐1.64) | .01 |

| Platelet count, a ×109/L (n = 101) | 197.10 ± 66.25 | 198.27 ± 69.81 | 196.04 ± 63.52 | .87 |

| Procalcitonin, b μg/L (n = 101) | 0.04 (0.02‐0.05) | 0.03 (0.03‐0.05) | 0.04 (0.02‐0.05) | .47 |

| C‐reaction protein, b mg/L (n = 82) | 11.75 (3.55‐32.73) | 11.35 (3.11‐31.75) | 11.95 (4.86‐41.58) | .29 |

| Erythrocyte sedimentation rate, b mm/h (n = 70) | 35.00 (20.00‐58.30) | 40.50 (18.50‐89.00) | 32.00 (20.00‐50.00) | .22 |

| Triglyceride, b mmol/L (n = 75) | 1.63 (1.00‐2.85) | 2.21 (1.18‐3.37) | 1.43 (0.93‐1.88) | .01 |

| Low‐density lipoprotein, a mmol/L (n = 75) | 2.02 ± 0.68 | 2.00 ± 0.67 | 2.03 ± 0.69 | .87 |

| High density lipoprotein, b mmol/L (n = 75) | 0.89 (0.77‐1.06) | 0.91 (0.79‐1.02) | 0.87 (0.77‐1.15) | .98 |

| Total cholesterol, b mmol/L (n = 75) | 3.73 (3.18‐4.41) | 3.72 (3.15‐4.45) | 3.74 (3.24‐4.40) | .96 |

| D‐dimer, b mg/L (n = 100) | 0.47 (0.19‐0.70) | 0.45 (0.19‐0.64) | 0.51 (0.19‐0.74) | .46 |

| Hemoglobin, a g/L (n = 101) | 137.74 ± 16.64 | 138.52 ± 14.82 | 137.04 ± 18.24 | .66 |

| Alkaline phosphatase, b IU/L (n = 95) | 58.80 (51.00‐72.20) | 57.00 (49.00‐73.15) | 60.55 (51.75‐72.05) | .35 |

| Alanine aminotransferase, b IU/L (n = 102) | 20.00 (15.00‐34.25) | 19.75 (13.68‐31.98) | 20.50 (15.25‐41) | .36 |

| Aspartate aminotransferase, b IU/L (n = 102) | 26.00 (20.83‐34.08) | 25.65 (20.25‐33.73) | 26.50 (21.58‐34.25) | .61 |

| Total bilirubin, b μmol/L (n = 102) | 10.90 (7.55‐16.65) | 11.04 (7.6‐19.62) | 10.64 (7.26‐14.01) | .23 |

| Direct bilirubin, b μmol/L (n = 102) | 3.80 (2.45‐5.97) | 4.50 (2.13‐6.37) | 3.45 (2.48‐5.15) | .34 |

| Total protein, a g/L (n = 102) | 69.11 ± 6.41 | 70.70 ± 6.03 | 67.71 ± 6.46 | .02 |

| Globulin, b g/L (n = 102) | 30.81 (25.56‐38.50) | 33.49 (26.52‐39.94) | 28.69 (24.24‐36.20) | .05 |

| Albumin, a g/L (n = 102) | 37.35 ± 6.92 | 37.43 ± 6.33 | 37.29 ± 7.46 | .92 |

| Creatinine, a μmol/L (n = 102) | 66.09 ± 17.88 | 64.17 ± 16.62 | 67.81 ± 18.92 | .31 |

| Creatine kinase, b U/L (n = 102) | 71.00 (51.23‐131.25) | 71.50 (52.50‐120.25) | 69.50 (50.99‐140.78) | .92 |

| Myohemoglobin, b μg/L (n = 102) | 50.32 (38.50‐73.77) | 49.68 (40.00‐71.35) | 50.82 (35.27‐87.83) | .91 |

| Potassium, a mmol/L (n = 103) | 3.87 ± 0.47 | 3.92 ± 0.45 | 3.83 ± 0.49 | .32 |

| Sodium, a mmol/L (n = 103) | 139.89 ± 5.45 | 140.68 ± 4.84 | 139.20 ± 5.89 | .17 |

| Calcium, a mmol/L (n = 103) | 2.14 ± 0.20 | 2.11 ± 0.19 | 2.16 ± 0.21 | .25 |

| CT finding | ||||

| Bilateral distribution of patchy shadows or ground‐glass opacity, no. (%) (n = 94) | 75 (79.79) | 38 (82.61) | 37 (77.08) | .51 |

| Outcomes | .45 | |||

| Ongoing treatment | 7(6.73) | 2 (4.17) | 5 (8.93) | |

| Death | 1 (0.96) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.79) | |

| Discharge | 96 (92.31) | 46 (95.83) | 50 (89.28) | |

Abbreviations: COVID, coronavirus disease; SD, standard deviation.

mean ± SD.

median (range).

The incubation period of emigrated cases is the time from leaving Wuhan to onset symptoms, there were 44 cases; the incubation period of indigenous cases is the time from exposure to onset symptoms, there were 27 cases.

Others include nausea, chest congestion, anorexia, stuffiness, emesis, abdominal distension, dry mouth, dry throat, acid reflux, and dizziness. P values comparing emigrated cases and indigenous cases are from the Student t test, χ 2 test, Fisher's exact test, or the Mann‐Whitney U test.

For the white cell count, 15 cases (14.85%) were below the normal and 15 (14.85%) were above the normal level; 101 patients took the lymphocyte count test and results showed 63 (62.38%) of them were below the normal level; 82 patients took the C‐reactive protein test and 53 (64.63%) of them were above the normal level; 101 patients took the procalcitonin test and all reported the normal level; 70 patients took the test of erythrocyte sedimentation rate and 51 (72.86%) of them were above the normal level; 25 patients took the IL‐6 test and 10 (40%) of them were above the normal level. For the D‐dimer test, 44 (44%) patients reported the normal level. Just 19 patients took the CD4 and CD8 count test and 17 of them reported a lower level of CD4 and 9 lower level of CD8. Compared with the emigrated patients, indigenous patients had higher lymphocyte counts, lower level of triglyceride, total protein, and globulin, no significant differences of the other laboratory parameters between the two group was observed. As we followed until 23 February 2020, 96 (92.31%) patients discharged and 1 (0.96%) died, the rest 7(6.73%) patients stayed in the hospital.

4. DISCUSSION

Here, we report the transmission and clinical characteristic of 104 outside‐Wuhan patients with COVID‐19. First, the smooth increase in the cumulative number of confirmations of the two centers indicates that the timely control measures work well. Second, family clusters represent the major body of infections, and transmission along the chain of three “generations” was observed. The asymptomatic transmission demonstrated here warned us that it may bring more risk to the spread of COVID‐19. Third, no gender difference of patients was found, indicating male and female may have the same susceptibility of this illness. Fourth, the differences in demographics and clinical characteristics between emigrated patients and indigenous cases were not significant.

Since the outbreak in Wuhan, it is unclear how many people truly got infected and how many infected people of Wuhan emigrated to the other cities. Screening the potential infectors related to Wuhan was implemented quickly by the local governments after the announcement of Wuhan shutdown. Dynamic analysis of 104 cases from two centers in Hunan province showed that the emigrated cases mainly appeared during 22 January 2020–5 February 2020, and then, the indigenous cases became the major infecting bodies, suggesting that the initial cases were found over nearly 20 days of screening. Compared with the contemporary growth trend in Wuhan, a rapid increase in the confirmed cases was not observed in the two centers from 22 January 2020 to 12 February 2020, indicating that the timely control measures in the two cities worked well.

Yet fundamental information gaps exist on how to accurately assess the transmission efficiency. With the sharp increase in cases and medical shortage in the early and outbreak stage in Wuhan, patients in Wuhan may have faced limitation to fully reflect the true epidemiological characteristics of this illness. Evidence has suggested person‐to‐person transmission of COVID‐19 via droplets or skin touch. 2 , 3 , 11 The data of this study showed a notable feature is clustering occurrence, and most patients were infected from their family members, relatives, or friends through close contact. Only 11 (10.53%) of this study patients were sporadic cases that could hardly identify infector source, suggesting that community transmission of COVID‐19 did not develop rapidly in the two cities; this also matches the smooth growth of total confirmed cases. Of note, strict control measures taken by the local government had a powerful effect on slowing down the spread.

We are eager to know how infectious the virus is. Except the confirmed cases, whether the asymptomatic COVID‐19 carriers are infectious is still unclear. A recent study showed that the viral load in the asymptomatic patient was similar to that in the symptomatic patients. 12 Our study directly demonstrated that the asymptomatic patient or viral‐carries infected their relatives. Three cases (C37, C44, and C49) got infected from the same person (C'3) whoever traveled to Wuhan. But until now, C'3 did not develop any symptoms. Though we did not take a PCR test to confirm whether C'3 was a virus carrier, the same contact history and the similar onset time of her three relatives indicated that C'3 was an asymptomatic COVID‐19 carrier. Five asymptomatic patients were found in this study, one patient (C'4) who infected three family members (C92, C94, and C102) provided evidence that the asymptomatic transmission risks the spread of COVID‐19, which makes it more difficult to cut off the epidemic's transmission route. We surveyed eight infected couples, a total of three infants closely lived with their parents, but none of them was infected. Just three children were infected from their parents or relatives. These observations further demonstrated that infants and children are not so susceptible as adults, which is consistent with the previous reports. 2 , 3 , 6 , 13 Unlike the other reported populations, no nosocomial transmission was found in the two centers. 2 The safeguard of protective equipment and the strength of nosocomial infection control may play key roles in the zero accident of hospital‐related infection.

The incubation duration ranged from 1 to 32 days with the median time of 6 days, which was similar to the reported patients. 14 A recent report warned us that the incubation duration may extend to 24 days. 15 We also found the incubation duration of eight patients ranged from 18 to 32 days, indicating that it may exceed 14 days that reported with the initial infections. 3

No significant differences in demographics between emigrated patients and indigenous patients were observed. Unlike some earlier reports, 3 , 6 here, no gender difference was found among the study patients (47.12% patients were male). This is consistent with a recent report of 138 Wuhan patients. 2 This report further provides evidence that male and female may have the same susceptibility of this illness. This study patients were younger than that of reported patients. It may be related to the patients' job characteristics and social relationship. With the Spring Festival coming, young or middle‐aged people are more likely to attend a social activity, which could result in person‐to‐person transmission. Common symptoms of onset were similar to the reported patients. 16 The atypical symptoms such as diarrhea, nausea, and runny nose make it more difficult to diagnose precisely. Patients who required ICU care were just 8.65%. With the increased awareness of early discovery and timely treatment, organ function damage occurred just in few patients, which is quite different from observation of patients in Wuhan. Studies suggested that COVID‐19 may attack human's immune system which results in cytokine storm. 3 The lymphocyte counts of this study patients were below the normal. Here, 17 of 19 patients showed a significant decrease in CD4 cell counts, and 9 of 17 patients showed a decrease in CD8 cell counts, and it is a pity that the rest of the patients did not take the test. We still do not know the pathogenic mechanism of COVID‐19, so we should take a route test of the CD4 and CD8 counts for better understanding this illness. The higher rate of discharge (38.46%) and lower mortality (0.96%) of this study population may mainly attribute to the relatively superior treat conditions, including enough healthcare worker and single ward for every patient. In addition, psychological intervention was also performed to patients.

This study has several limitations. First, just two centers of Hunan Province were included, and there is limited information based on the data to fully assess the transmission and clinical characteristics in outside‐Wuhan cities. Second, all patients were confirmed by RT‐PCR through nasopharyngeal or throat swab, and it could not reflect viral load change in blood or organs. Until now there is confusion about whether the severity of COVID‐19 is related to changes of viral load in blood. Third, the follow‐up period is not long enough to examine the outcomes of all the included patients.

In conclusion, the timely control measures after the Wuhan shutdown reduced the spread of COVID‐19 in the two cities. Family but not community transmission became the main body of infections in the two centers. Asymptomatic transmission demonstrated here warned us that it may increase the risk of the spread of COVID‐19. A 14‐day quarantine may need to be prolonged.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The authors declare that there are no conflict of interests.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

CQ and DL conceived and designed the research. CQ drafted and revised the manuscript. ZD, QX, XL, HL, and DZ collected the data. ZD and HW checked the data. YS and YD conducted the statistical analysis. XZ, JZ, JW, and ZS conducted the contact investigation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Hunan Province, China (2017JJ3250 and 2019JJ40230), and the Project of Science and Technology of Health Commission of Hunan Province, China (B2019034 and B2019035).

Qiu C, Deng Z, Xiao Q, et al. Transmission and clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in 104 outside‐Wuhan patients, China. J Med Virol. 2020;92:2027–2035. 10.1002/jmv.25975

REFERENCES

- 1. Prevention CCfDCa . Distribution of the 2019‐nCoV Epidemic. 2020. http://2019ncov.chinacdc.cn/2019-nCoV/. Accessed 15 February 2020.

- 2. Wang D, Hu B, Hu C, et al. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus‐infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA. 2020;323:1061‐1069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395:497‐506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chan JFW, Yuan S, Kok KH, et al. A familial cluster of pneumonia associated with the 2019 novel coronavirus indicating person‐to‐person transmission: a study of a family cluster. Lancet. 2020;395:514‐523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chen ZL, Zhang Q, Lu Y, et al. Distribution of the COVID‐19 epidemic and correlation with population emigration from Wuhan, China. Chin Med J (Engl). 2020;133(9):1044‐1050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chen N, Zhou M, Dong X, et al. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet. 2020;395:507‐513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. National Health Commission, General office of the national health commission, PRC. The diagnosis and treatment of COVID‐19 (The 7th edition of trial implementation). China Medicine. 2020;6:801‐805. [Google Scholar]

- 8. ARDS Definition Task F, Ranieri VM, Rubenfeld GD, et al. Acute respiratory distress syndrome: the Berlin Definition. JAMA. 2012;307(23):2526‐2533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kellum JA, Lameire NDiagnosis. Evaluation, and management of acute kidney injury: a KDIGO summary (part 1). Crit Care. 2013;17(1):204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. NIfVDCaP (China) . Specific primers and probes for detection 2019 novel coronavirus. 2020. http://ivdc.chinacdc.cn/kyjz/202001/t20200121_211337.html. Accessed 28 January 2020.

- 11. Phan LT, Nguyen TV, Luong QC, et al. Importation and human‐to‐human transmission of a novel coronavirus in Vietnam. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:872‐874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Zou L, Ruan F, Huang M, et al. SARS‐CoV‐2 viral load in upper respiratory specimens of infected patients. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1177‐1179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Yang Y, Lu Q, Liu M, et al. Epidemiological and clinical features of the 2019 novel coronavirus outbreak in China. medRxiv. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Li Q, Guan X, Wu P, et al. Early transmission dynamics in Wuhan, China, of novel coronavirus‐infected pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1199‐1207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. W‐j Guan, Z‐y Ni, Hu Y, et al. Clinical characteristics of 2019 novel coronavirus infection in China. medRxiv. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Jin YH, Cai L, Cheng ZS, et al. A rapid advice guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of 2019 novel coronavirus (2019‐nCoV) infected pneumonia (standard version). Mil Med Res. 2020;7(1):4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]