Abstract

The severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS)‐CoV‐2 pandemic continues to produce a large number of patients with chronic respiratory failure and ventilator dependence. As such, surgeons will be called upon to perform tracheotomy for a subset of these chronically intubated patients. As seen during the SARS and the SARS‐CoV‐2 outbreaks, aerosol‐generating procedures (AGP) have been associated with higher rates of infection of medical personnel and potential acceleration of viral dissemination throughout the medical center. Therefore, a thoughtful approach to tracheotomy (and other AGPs) is imperative and maintaining traditional management norms may be unsuitable or even potentially harmful. We sought to review the existing evidence informing best practices and then develop straightforward guidelines for tracheotomy during the SARS‐CoV‐2 pandemic. This communication is the product of those efforts and is based on national and international experience with the current SARS‐CoV‐2 pandemic and the SARS epidemic of 2002/2003.

Keywords: COVID, critical care, head and neck surgery, otolaryngology, tracheostomy

1. INTRODUCTION

The severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS)‐CoV‐2 pandemic continues to produce a large number of patients with chronic respiratory failure and ventilator dependence. Surgeons will be called upon to perform tracheotomy for a subset of these chronically intubated patients. As seen during the SARS and the SARS‐CoV‐2 outbreaks, aerosol‐generating procedures (AGP) have been associated with higher rates of infection of medical personnel and potential acceleration of viral dissemination throughout the medical center. Therefore, a thoughtful approach to tracheotomy (and other AGPs) is imperative and maintaining traditional management norms may be unsuitable or even potentially harmful. In this backdrop, we sought to review the existing evidence informing best practices and then develop straightforward guidelines for tracheotomy during the SARS‐CoV‐2 pandemic. This communication is the product of those efforts and is based on national and international experience with the current SARS‐CoV‐2 pandemic and the SARS epidemic of 2002/2003.

Our priorities in establishing these guidelines included: optimal patient care, protection of medical personnel, minimizing further spread of the virus and preservation of important resources (ICU beds, ventilators, and PPE). These recommendations represent a consensus of stakeholders from our medical center including otolaryngologists, trauma surgeons, interventional pulmonologists, anesthesiologists, and critical care providers.

2. SARS EXPERIENCE

Due to the paucity of data regarding the current SARS‐CoV‐2 epidemic, the literature from the SARS epidemic of 2002 and 2003 was reviewed. 1 The initial SARS case was recorded in November 2002 and the epidemic peaked in May 2003. In total, approximately 8096 patients were infected with 774 deaths. Twenty‐one percent of all cases occurred in health care workers. 1 There were clear features of respiratory transmission of disease during AGPs for patients with SARS. In Hong Kong (March 2003), a businessman was intubated at one hospital, and transported to another, leading to the infection of 37 health care workers involved in his care.

In Canada, 43% of cases occurred in health care workers as a result of AGPs.1, 2 One instance involved a difficult intubation of a patient who was under investigation for SARS. This intubation was linked to the infection of seven hospital staff all of whom had been wearing full PPE including N95 masks during patient contact. 2

3. SUCCESSFUL TRACHEOTOMY DURING SARS

There are multiple reports3, 4 of safely performing tracheotomy on patients with SARS without infecting health care workers. Standard processes included strict infection control measures, seamless and regulated surgical intervention, and if possible delayed (>30 days from diagnosis) tracheotomy in patients who had been SARS positive. Infection control measures (in addition to standard airborne and contact precautions) taken during these procedures included: double gowning, PAPR suits, double gloving, a changing room after the procedure (ante room), performing the procedure in a negative pressure room. The surgical personnel were the most experienced available to minimize operating/exposure time. Patients were completely paralyzed to minimize air movement and coughing and thus viral dissemination via aerosolization. Prior to the procedure, a trial run was completed to ensure maximum efficiency of the procedure. Just prior to airway entry, the patients were pre‐oxygenated, ventilation was held, and the cuff on the endotracheal tube was dropped to minimize air movement over the respiratory mucosa. While the patient was apneic, the tracheotomy incision was performed. Open suctioning of the trachea was avoided. Instead, a closed suctioning system with a viral filter was used.3, 4

4. OTOLARYNGOLOGY EXPERIENCE WORLDWIDE WITH SARS‐COV‐2

During the current SARS‐CoV‐2 pandemic, reports from multiple countries suggest that Otolaryngologists and support staff are at a unique risk of SARS‐CoV‐2 exposure. An early case in China with devastating results involved endoscopic pituitary surgery in a patient with flu‐like symptoms. 5 Contact tracing confirmed that 14 health care workers became infected with SARS‐CoV‐2 from this one procedure. In Wuhan, otolaryngologists and ophthalmologists were among the most commonly infected health care workers. N95 masks did not appear to completely prevent infection of health care workers. PAPR suits were more effective. 5 In Iran, over 20 Otolaryngologists have been hospitalized after testing positive for SARS‐CoV‐2 with at least two deaths, including a chief resident. 5 Two ENT physicians required ventilator support in the United Kingdom, with at least one ultimately succumbing to the infection. To date, over 60 physicians have died in Italy as a result of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection. 6 In Spain, over 12 000 health care workers have tested positive for the disease (14.4% of total reported cases). 7 In the United States, Ohio and Minnesota have reported 16%‐28% of their COVID positive cases involve health care workers. 7 The American Academy of Otolaryngology: Head and Neck Surgery has recommended a multidisciplinary approach in determining indications for tracheotomy in patients with SARS‐CoV‐2. In addition to the necessity of donning appropriate PPE, they recommend not performing tracheotomy until 2‐3 weeks postintubation and repeat SARS‐CoV‐2 testing is negative. The procedures should be performed under a closed circuit with a minimal number of care providers and duration of procedure. 8

Emergent tracheostomy secondary to upper airway distortion or obstruction precluding endotracheal intubation has not been reported in patients with SARS‐CoV‐2. Early experience suggests that patients with SARS‐CoV‐2 produce relatively little mucus and secretions in relation to other causes of respiratory failure. For these reasons, tracheotomy appears less critical for pulmonary toilet for patients with SARS‐CoV‐2. 9

5. RECOMMENDATIONS FOR TRACHEOTOMY DURING SARS‐COV‐2 PANDEMIC

As the number of infected patients requiring intubation and ventilator support climbs, a growing population of patients would normally qualify for tracheotomy due to failed extubation or prolonged ventilatory needs. Considering the clear evidence from both SARS and SARS‐CoV‐2 infection, 9 it is imperative that this patient population be managed appropriately to minimize infectious risk to the health care team.

Currently, there are no published reports on tracheotomy in patients with COVID‐19. We felt there were numerous reasons to develop consensus guidelines including:

An anticipated high volume in our center (third largest public hospital in the United States).

Known risk to intraoperative and postoperative medical staff.

Anticipated shortages of resources (ICU beds, ventilators, PPE) which could be impacted by decisions around tracheotomy.

High potential for conflict between surgeons and critical care staff over an emotionally charged issue.

To address these concerns, we assembled a task force of stakeholders in our medical center involved with tracheotomy including otolaryngology, trauma surgery, critical care medicine, and anesthesiology. The group reviewed existing literature and met virtually to draft recommendations. Ideas were refined with final recommendations approved by all Task Force members as summarized below. The availability of highly predictive testing for SARS‐CoV‐2 has greatly simplified the decision process in our medical center; improving the safety of medical staff, preserving resources like PPE and freeing up resources like ventilators and ICU space.

6. TRACHEOTOMY MANAGEMENT AND IMPLEMENTATION

6.1. Decision for tracheotomy in patients with COVID‐19

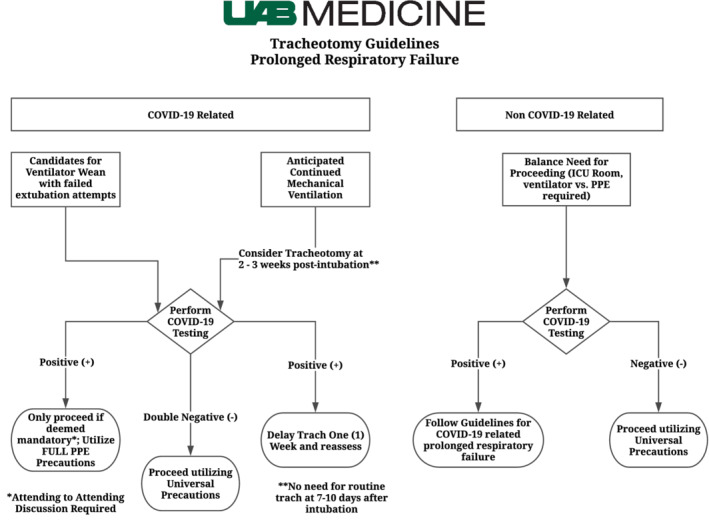

Tracheotomy in patients with active COVID‐19 and severe respiratory failure should be exceedingly rare (Figure 1). In patients with prolonged intubation, elective tracheotomy can be delayed well beyond the usual 14‐day timeline. Despite concern for airway stenosis due to prolonged intubation, recent data suggests early tracheotomy may be less crucial and the safety issues around the pandemic outweigh the risks of late airway stenosis. 10

- If a tracheotomy is to be performed in a COVID‐19 positive patient, it should be conducted with the following in mind:

- Procedures should be completed in the ICU at bedside to avoid risk of exposure during transport. Furthermore, there may be more access to negative pressure rooms in the ICU setting.

- It is unclear whether open tracheotomy or percutaneous tracheotomy produces less aerosolized viral particles. Each procedure should be permitted until more data is available. Percutaneous tracheotomy has been performed in the ICU setting in our institution for a number of years. 11

- Staff should be minimized and should only include absolutely essential personnel.

- For open tracheotomy and percutaneous tracheotomy, key recommendations include minimizing opportunity for aerosolization:

- complete paralysis to avoid coughing;

- ventilation only with cuff inflation;

- stopping ventilation prior to entering the airway and deflating the cuff;

- avoiding suctioning once the trachea is incised due to the risk of aerosolization of high viral load secretions;

- minimizing cautery due to concerns of aerosolization of viral particles in the smoke plume;

- minimize bronchoscopy time as much as possible (for percutaneous tracheostomy);

- minimal PPE worn by staff should include N95, mask with shield, surgical gown, double gloves. PAPR and/or AAMI level 4 suit (ie, ‐Stryker T4) is preferable if available.

- For percutaneous tracheotomy, bronchoscopy time should be minimized as much as possible.

- Procedures should be performed in a negative pressure room if available.

- HEPA filter “air scrubber” should be placed in the room, if available, for tracheotomies on patients with COVID positive .

FIGURE 1.

Tracheotomy guidelines in the COVID‐19 era [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

6.2. Decision for elective tracheotomy in patients with COVID‐19 negative

Tracheotomy should not be performed in the “person under investigation” population unless deemed an emergency.

For all planned tracheotomy procedures, patients are required to have two negative COVID‐19 swabs (separated by 24 hours) from the nasopharynx. This may be dependent on institution, but at this medical center, two negative nasopharyngeal swabs is thought to be adequate based on discussion with infectious disease faculty.

Consider early tracheotomy (in non‐COVID positive) for intubated patients that may require long‐term ventilation to free up ICU space and ventilators.

If elective tracheotomy is necessary on COVID negative patients with two negative swabs negative testing (above part 2), this can proceed as normal. However, it is still advised to use airway precautions. However, it is still advised to implement the same precautions as patients with SARS‐CoV‐2 positive if resources allow.

6.3. Emergency tracheotomy

Emergency tracheotomy should be performed as indication necessitates (tumor, stenosis, trauma, etc.).

If COVID testing is not available, patients should be presumed as COVID‐positive and treated as above with enhanced airway precautions.

6.4. Personal protective equipment

Surgical tracheotomy or tracheotomy tube change are procedures with high risk for aerosol generation. PPE guidance for these procedures should be the same as for bronchoscopy or any airway procedure that disrupts aerodigestive tract mucosa. Currently, this involves N95 mask, face shield, gown, and shoe covers for all patients WITHOUT known or suspected coronavirus infection. Double gloves are recommended with removal of outer gloves before removing PPE.

PAPR is additionally recommended for all personnel in the room during surgical tracheostomy in patients WITH known or suspected COVID‐19.

6.5. Post‐tracheostomy care

- For COVID‐19 positive patients or those in whom status is unknown:

- Enhanced droplet precautions as is standard for all patients with COVID (N95, face mask, gown, gloves).

- All tracheotomy suctioning should be performed using a closed suction system with viral filter.

- Keep cuff inflated.

- Delay first tracheotomy tube change to 3‐4 weeks, if possible avoid changing tracheotomy tube until after COVID has passed.

- For patients with COVID‐19 negative

- PPE for all tracheotomy care should include surgical mask, face shield, gown, and gloves.

7. CONCLUSION

The SARS‐CoV‐2 pandemic is rapidly evolving with continuous updates in treatment and guidelines. At the time of writing, there were over 492 000 cases in the United States with almost 19 000 deaths. 12 The management algorithm recommended by our multidisciplinary team draws on experiences with the 2002‐2003 SARS epidemic and the current experience of surgeons, anesthesiologists, Intensivists, and other health care workers with SARS‐CoV‐2. The goals of these recommendations are to provide optimal patient care, protection of medical personnel, minimizing further spread of the virus, and preservation of important resources (ICU beds, ventilators, and PPE).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Michel Thomas for his assistance in the graphic design of our flowchart.

Skoog H, Withrow K, Jeyarajan H, et al. Tracheotomy in the SARS‐CoV‐2 pandemic. Head & Neck. 2020;42:1392–1396. 10.1002/hed.26214

REFERENCES

- 1. Cherry JD. The chronology of the 2002‐2003 SARS mini pandemic. Paediatr Respir Rev. 2004;5(4):262‐269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ofner M, Lem M, Sarwal S, Vearncombe M, Simor A. Cluster of severe acute respiratory syndrome cases among protected health care workers‐Toronto, April 2003. Can Commun Dis Rep. 2003;29(11):93‐97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kwan A, Fok WG, Law KI, Lam SH. Tracheostomy in a patient with severe acute respiratory syndrome. Br J Anaesth. 2004;92(2):280‐282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wei WI, Tuen HH, Ng RW, Lam LK. Safe tracheostomy for patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome. Laryngoscope. 2003;113(10):1777‐1779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Patel ZM, Fernandez‐Miranda J, Hwang PH, et al. Precautions for endoscopic transnasal skull base surgery during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Neurosurgery. 2020. 10.1093/neuros/nyaa156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chustecka Z. More than 60 doctors in Italy have died in COVID‐19 pandemic. https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/927753. 2020. Accessed April 8, 2020.

- 7. Bellisle M. How many medical workers have contracted COVID‐19? Oregon Public Broadcasting. https://www.opb.org/news/article/coronavirus‐covid‐19‐data‐health‐care‐medical‐workers‐infection. Accessed April 8, 2020.

- 8. Parker N, Bradley MD; Fritz, M ; Rapoport, S ; Schlid, S ; Altman, K ; Merati, A ; Kuhn, M . AAO position statement: tracheotomy recommendations during the COVID‐19 pandemic. 2020. https://www.entnet.org/content/tracheotomy-recommendations-during-covid-19-pandemic. Accessed March 27, 2020.

- 9. Vukkadala N, Qian ZJ, Holsinger FC, Patel ZM, Rosenthal E. COVID‐19 and the otolaryngologist—preliminary evidence‐based review. Laryngoscope. 2020. 10.1002/lary.28672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Curry SD, Rowan PJ. Laryngotracheal stenosis in early vs late tracheostomy: a systematic review. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2020;162(2):160‐167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. White HN, Sharp DB, Castellanos PF. Suspension laryngoscopy‐assisted percutaneous dilatational tracheostomy in high‐risk patients. Laryngoscope. 2010;120(12):2423‐2429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) cases in the US. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/cases-updates/cases-in-us.html. Accessed April 9, 2020.