Abstract

The management pathways of advanced renal cell carcinoma (RCC) have considerably evolved in the past 5 years, presenting a particular challenge during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. In this Comment, we propose a management algorithm on the basis of the current evidence to safely manage patients with advanced RCC during this pandemic.

Subject terms: Renal cell carcinoma, Surgical oncology

The pandemic of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection resulted in a major redistribution of health-care resources to combat this global public health emergency1. Temporary restructuring of health-care delivery has been required to meet the demand of COVID-19 while providing quality care for routine health needs, including cancer therapy. Preliminary data suggest that patients with cancer are at an increased risk of developing severe complications from COVID-19 (ref.2). To avoid SARS-CoV-2 infection, a part of the treatment strategy for oncology patients is to delay elective procedures, forego unnecessary testing and consider deferring treatment until the risk of COVID-19 subsides. Cancer societies and national authorities have already issued guidelines on cancer care during the COVID-19 pandemic3. The goal of treatment is to maintain favourable clinical outcomes while limiting exposure to SARS-CoV-2 and potential adverse effects of infection resulting in prolonged hospitalizations.

The goal of treatment is to maintain favourable clinical outcomes while limiting exposure to SARS-CoV-2 and potential adverse effects of infection

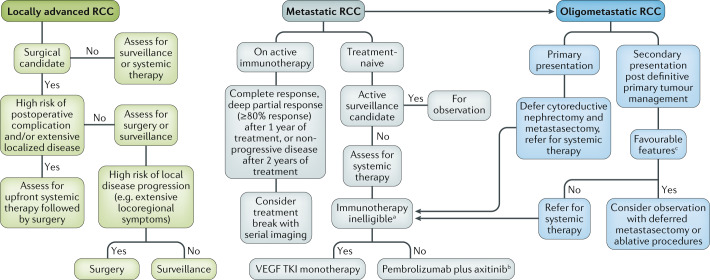

In the past 5 years, the therapeutic landscape of advanced RCC has considerably evolved, resulting in multiple approved therapeutic options, which has added substantial complexity to clinical decision-making. This situation poses a challenge during the COVID-19 pandemic, forcing a re-evaluation of management strategies in these unprecedented times. Here, we propose a treatment algorithm for patients with advanced RCC, which reduces the risk of exposure to SARS-CoV-2 but still emphasizes good clinical practice (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Proposed management algorithm for advanced renal cell carcinoma during COVID-19.

Our personal recommendations during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic on the management of patients with locally advanced, metastatic and oligometastatic renal cell carcinoma (RCC). VEGF TKI, vascular endothelial growth factor tyrosine kinase inhibitor. aPatients with a history of an active autoimmune condition, with a previous life-threatening autoimmune condition, receiving chronic immunosuppressive medication or with other high-risk features of developing immune-related adverse events (irAEs). bIn patients with an intermediate risk of developing irAEs, such as patients with psoriasis, coeliac disease or type 1 diabetes mellitus, consider upfront axitinib monotherapy followed by addition of pembrolizumab when COVID-19 risk subsides. cFavourable features in the oligometastatic setting include >12-month disease-free interval after nephrectomy, low-grade tumour, good performance status and lung-only metastasis.

For patients with locally advanced RCC, upfront surgical resection is the standard of care. Surgical resection requires extensive use of personal protective equipment and, usually, overnight hospitalizations with an increased risk of exposure to SARS-CoV-2 for patients, providers and hospital staff. A theme throughout this Comment is that surgical therapy (and the subsequent use of valuable resources) can often be deferred in favour of effective systemic therapy, which does not require hospital admissions. Surgery should be prioritized for those patients at greatest risk of disease progression or complications from the disease if untreated. For patients with a high risk of postoperative complications or evidence of extensive localized disease (for example, inferior vena cava thrombus and extensive retroperitoneal lymphadenopathy), deferral of immediate surgical intervention can be considered. These patients can start systemic therapy, with a plan to address the surgical intervention in the next few months. The selection of systemic therapy should be weighed between the risk of bleeding when receiving vascular endothelial growth factor tyrosine kinase inhibitors (VEGF TKIs) and the risk of hospitalization from immune-related adverse events (irAEs) from immuno-oncology agents. Single-agent VEGF TKIs might be ideal in this circumstance. These agents are orally administered at home, and patients can be managed through telemedicine. Toxic effects can be managed with supportive care or drug cessation and, usually, do not require inpatient management. Surgery can be reconsidered after 3 months or sooner when elective surgeries resume at each institution.

The treatment of patients with metastatic RCC has continued to evolve over the past few years. The CARMENA and SURTIME trials investigated the benefit of upfront and delayed cytoreductive nephrectomy, respectively4. Although the interpretation of these studies was limited by several caveats in study enrolment and analysis, their findings suggest limited benefits of cytoreductive nephrectomy and a lack of harm by choosing upfront systemic therapy. Currently, cytoreductive nephrectomy is considered in highly select patients without extensive metastatic burden or poor-risk disease. However, in the COVID-19 era, we propose to consider upfront cytoreductive nephrectomy as a non-essential surgical procedure unless there are severe symptoms from the primary tumour5; thus, we recommend deferral of cytoreductive nephrectomy and consideration of systemic therapy for patients with intermediate-risk or poor-risk disease.

Systemic therapy of patients with treatment-naive metastatic RCC has undergone a radical shift in the past 2 years and immunotherapy-based combination treatments are now the standard of care. However, these patients are at risk of serious organ-specific irAEs (≥ grade 3), requiring long courses of immunosuppressive therapy, with a particular concern during this pandemic for the development of immunotherapy-related pneumonitis, which can mimic COVID-19-induced pneumonia. Notably, 27% and 29% of patients who received pembrolizumab plus axitinib in the KEYNOTE-426 trial6 and nivolumab plus ipilimumab in the CheckMate 214 trial7, respectively, received oral prednisone doses equivalent to ≥40 mg/day to manage select irAEs. The regimen of nivolumab plus ipilimumab was also associated with a higher risk of irAEs than pembrolizumab plus axitinib, including a higher risk of immune-related pneumonitis (6% versus 2.8%, respectively). For treatment-naive metastatic disease, we recommend pembrolizumab plus axitinib as the preferred frontline regimen during the COVID-19 pandemic, given the lower risk of irAEs than with the nivolumab plus ipilimumab regimen and benefit regardless of disease risk scores (pembrolizumab plus axitinib versus sunitinib overall survival HR 0.43, 0.53 and 0.64 in poor-risk, intermediate-risk and favourable-risk disease, respectively)6. In select patients with suspicion of an intermediate risk of developing irAEs, a sequential approach of upfront axitinib monotherapy followed by the addition of pembrolizumab when the risk of COVID-19 subsides might be considered. However, with the anticipated decline in COVID-19 rates and the availability of more detailed studies on the effect of COVID-19 on patients with cancer, both immunotherapy regimens can be considered according to the current existing guidelines, taking into account the constantly evolving COVID-19 pandemic and the possibility of future spikes in infection. If patients are deemed ineligible for immunotherapy owing to an increased risk of developing irAEs, then VEGF TKI monotherapy can be offered. Given the diverse clinical presentations of metastatic RCC, timely initiation of systemic therapy is not warranted in all cases. Asymptomatic patients with low disease volume and a favourable risk score can undergo active surveillance without compromising the benefit of treatment when initiated at a later date8.

To date, the optimal duration of immunotherapy treatment in metastatic RCC is not well defined. Patients in the KEYNOTE-426 trial6 received pembrolizumab for a maximum of 2 years; by contrast, immunotherapy was continued indefinitely in the CheckMate 214 trial7. In 2019, the Society for Immunotherapy of Cancer published updated recommendations on immunotherapy in RCC. Of 19 panel members, 94% and 56% recommended stopping immunotherapy in the setting of complete radiological response or non-progressive disease after 2 years of treatment, respectively9. During the COVID-19 pandemic, we propose to extend these recommendations to patients with deep partial responses (≥80% radiological tumour burden reduction) and consider cessation of therapy after 1 year of therapy. These patients can be followed with serial imaging, and immunotherapy can be resumed should evidence of disease progression become evident.

A subset of patients will present with oligometastatic disease. Assessing the appropriateness of surgical metastasectomy or ablative procedures is a standard approach in these patients. Favourable features, such as prolonged disease-free interval after nephrectomy (>12 months), good performance status, low-grade tumours and lung-only metastasis, are associated with better outcomes in the oligometastatic setting10. During the COVID-19 pandemic, we propose deferring metastasectomy and ablative procedures. Some patients might require upfront systemic therapy with the consideration of metastasectomy at a later time point. Active surveillance is also an option in select patients with limited disease burden and slow progression.

As COVID-19 might become a long-term public health problem, updated guidelines by the kidney cancer community might be warranted

Finally, providing adequate support to our patients is crucial throughout this pandemic. For patients with cancer, concerns over receiving inadequate care can surpass the perceived risk of COVID-19. In a survey by the Kidney Cancer Research Alliance (KCCure) of >500 patients with RCC in the USA, 71% of the participants felt that they were at a high risk of contracting COVID-19; however, 50% were either unwilling or very unwilling to skip an infusion of systemic therapy, and 64% were anxious about disease progression if systemic therapy was delayed (KCCure patient survey). Oncologists and surgeons caring for patients with RCC should reassure them that for many patients deferring therapies and avoiding the risks of SARS-CoV-2 exposure are in their best interest. Further studies are needed to gain insight into the effects of COVID-19 on cancer, particularly RCC. As COVID-19 might become a long-term public health problem, updated guidelines by the kidney cancer community might be warranted.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Related links

KCCure patient survey: https://kccure.org/2020/03/covid-19-kidney-cancer-patient-survey/

References

- 1.Wang C, Horby PW, Hayden FG, Gao GF. A novel coronavirus outbreak of global health concern. Lancet. 2020;395:470–473. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30185-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liang W, et al. Cancer patients in SARS-CoV-2 infection: a nationwide analysis in China. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21:335–337. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30096-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burki TK. Cancer guidelines during the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21:629–630. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30217-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bhanvadia S, Pal SK. Cytoreductive nephrectomy: questions remain after CARMENA. Nat. Rev. Urol. 2018;15:530–532. doi: 10.1038/s41585-018-0064-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Larcher A, et al. Individualised indications for cytoreductive nephrectomy: which criteria define the optimal candidates? Eur. Urol. Oncol. 2019;2:365–378. doi: 10.1016/j.euo.2019.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rini BI, et al. Pembrolizumab plus axitinib versus sunitinib for advanced renal-cell carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019;380:1116–1127. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1816714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Motzer RJ, et al. Nivolumab plus ipilimumab versus sunitinib in advanced renal-cell carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018;378:1277–1290. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1712126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rini BI, et al. Active surveillance in metastatic renal-cell carcinoma: a prospective, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17:1317–1324. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30196-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rini BI, et al. The society for immunotherapy of cancer consensus statement on immunotherapy for the treatment of advanced renal cell carcinoma (RCC) J. Immunother. Cancer. 2019;7:354. doi: 10.1186/s40425-019-0813-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tosco L, Van Poppel H, Frea B, Gregoraci G, Joniau S. Survival and impact of clinical prognostic factors in surgically treated metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Eur. Urol. 2013;63:646–652. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2012.09.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]