Abstract

Objective

Disease containment of COVID-19 has necessitated widespread social isolation. We aimed to establish what is known about how loneliness and disease containment measures impact on the mental health in children and adolescents.

Method

For this rapid review, we searched MEDLINE, PsycInfo, and Web of Science for articles published between January 1, 1946, and March 29, 2020. Of the articles, 20% were double screened using predefined criteria, and 20% of data was double extracted for quality assurance.

Results

A total of 83 articles (80 studies) met inclusion criteria. Of these, 63 studies reported on the impact of social isolation and loneliness on the mental health of previously healthy children and adolescents (n = 51,576; mean age 15.3 years). In all, 61 studies were observational, 18 were longitudinal, and 43 were cross-sectional studies assessing self-reported loneliness in healthy children and adolescents. One of these studies was a retrospective investigation after a pandemic. Two studies evaluated interventions. Studies had a high risk of bias, although longitudinal studies were of better methodological quality. Social isolation and loneliness increased the risk of depression, and possibly anxiety at the time at which loneliness was measured and between 0.25 and 9 years later. Duration of loneliness was more strongly correlated with mental health symptoms than intensity of loneliness.

Conclusion

Children and adolescents are probably more likely to experience high rates of depression and most likely anxiety during and after enforced isolation ends. This may increase as enforced isolation continues. Clinical services should offer preventive support and early intervention where possible and be prepared for an increase in mental health problems.

Key words: loneliness, pandemic, COVID-19, disease containment, mental health

The COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in governments implementing disease containment measures such as school closures, social distancing, and home quarantine. Children and adolescents are experiencing a prolonged state of physical isolation from their peers, teachers, extended families, and community networks. Quarantine in adults generally has negative psychological effects including confusion, anger, and posttraumatic distress.1 , 2 Duration of quarantine, fear of infection, boredom, frustration, lack of necessary supplies, lack of information, financial loss, and stigma appear to increase the risk of negative psychological outcomes.1 Social distancing and school closures may therefore increase mental health problems in children and adolescents, already at higher risk of developing mental health problems compared to adults3 at a time when they are also experiencing anxiety over a health threat and threats to family employment/income.

Social distancing and school closures are likely to result in increased loneliness in children and adolescents whose usual social contacts are curtailed by the disease containment measures. Loneliness is the painful emotional experience of a discrepancy between actual and desired social contact.4 Although social isolation is not necessarily synonymous with loneliness, early indications in the COVID-19 context indicate that more than one-third of adolescents report high levels of loneliness5 , 6 and almost half of 18- to 24-year olds are lonely during lockdown.7 There are well established links between loneliness and mental health.8 The purpose of this review was to establish what is known about the relationship between loneliness and mental health problems in healthy children and adolescents, and to determine whether disease containment measures including quarantine and social isolation are predictive of future mental health problems. We included cross-sectional, observational, retrospective, and case control studies if studies included mainly children and adolescents who had experienced loneliness or had used validated measures of social isolation and mental health problems. To capture the possible effects of social isolation and the expected mediator (ie, loneliness) on mental health problems, we included search terms to capture these two areas.

Method

We conducted a rapid review to provide a timely evidence synthesis to inform urgent healthcare policy decision making.9 A rapid review adheres to the essential principles of systematic reviews, including scientific rigor, transparency, and reproducibility. 9 , 10 It uses “abbreviated” systematic review methodology, including limiting search criteria, faster data extraction, and using narrative synthesis methods.11 , 12

Search Strategy and Selection Criteria

Table S1, Table S2, and Table S3, available online, provide the full search strategy. Briefly, we searched MEDLINE, PsycInfo, Web of Science, and the Cochrane Library. Our search terms were informed by recent rapid reviews in the COVID-19 context1 and included definitions of loneliness and social isolation to capture the impact of social distancing and school closures. Terms captured “children” or “adolescents” AND “quarantine” or “social isolation” or “loneliness” AND mental health related terms with a focus on the most common mental health problems in this age group, namely, depression and anxiety.

Peer-reviewed studies were selected according to the following inclusion criteria: published between 1946 and March 29, 2020; reported primary research; included predominantly children/adolescents (mean age <21 years)13; published in English (Web of Science only); participants had experienced either social isolation or loneliness; and valid assessment of depression, anxiety, trauma, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), mental health, or mental well-being.

Study Selection and Data Collection

We checked 20% of all study eligibility results (both included and excluded) to ensure adherence to the eligibility criteria. Data were extracted into a purpose-designed database. A random 20% of the data was double-entered to ensure accuracy.

A truncated quality assessment was conducted by one author (SR) using criteria adapted from the National Institutes of Health (NIH)14 (Table 1 ).

Table 1.

Quality Assessment Tool Adapted From National Institutes of Health14

| Were the exposure measures (independent variables) clearly defined, valid, reliable, and implemented consistently across all study participants? |

Yes: 1 No: 0 |

| Was the exposure measure objective (ie, not self-report) | Yes: 1 No: 0 |

| Were the outcome measures (dependent variables) clearly defined, valid, reliable, and implemented consistently across all study participants? |

Yes: 1 No: 0 |

| Was the outcome assessed objectively? | Yes or by blinded assessors: 2 By another individual, eg, parent: 1 No, ie, self-report: 0 |

| Were key potential confounding variables measured and adjusted statistically for their impact on the relationship between exposure(s) and outcome(s)? |

No or unclear: 0 Some attempt, eg, SES, demographics: 1 Reasonable or comprehensive, eg, baseline depression for longitudinal studies, other exposure to stress or adversity, negative affectivity: 2 |

| Is a longitudinal design with exposure measured before outcome? |

Yes: 1 No: 0 |

| Longitudinal only | |

| Was loss to follow-up after base line 20% or less? | Yes: 1 No: 0 |

| Were the exposure(s) assessed more than once over time? | Yes: 1 No: 0 |

Note: Exposure measures indicate independent variables. SES = socioeconomic status.

Data Synthesis

We conducted a narrative synthesis within the following categories: (1) the impact of loneliness on mental health in healthy populations (further divided into cross-sectional and longitudinal evidence); (2) pandemic-specific findings; and (3) intervention studies.

Results

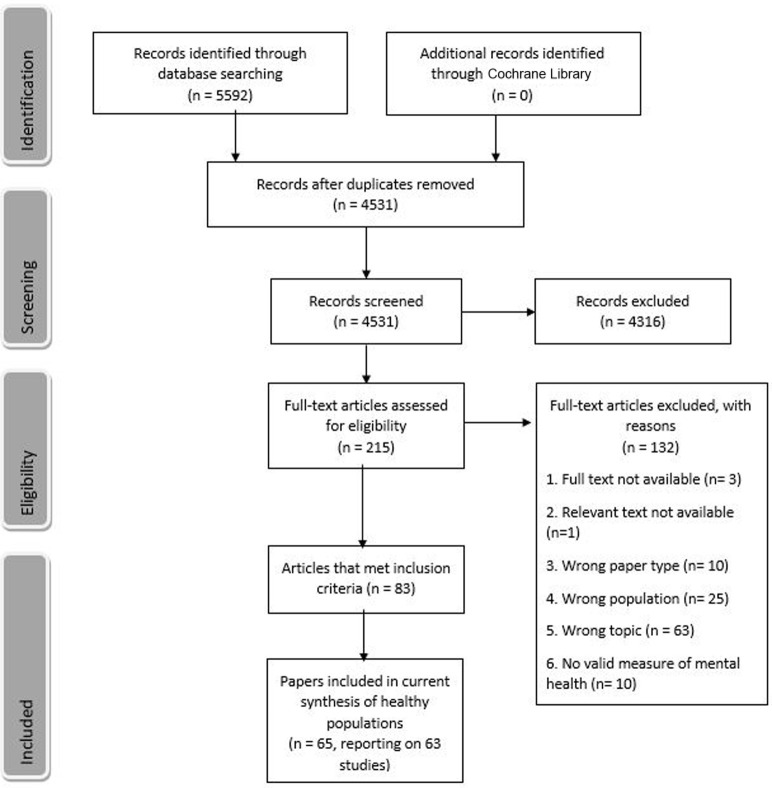

We located 4,531 articles (Figure 1 ), of which 83 articles (80 studies) met the inclusion criteria. Of these, 18 articles (17 studies) reported on the impact of loneliness in individuals with a variety of health conditions, including mental health problems (12 studies), physical health problems (one study) and neurodevelopmental conditions (4 studies). The remaining 65 articles reported on 63 studies that examined the impact of loneliness or disease containment measures on healthy children and adolescents. For the purposes of this rapid review, we will focus our analyses on these 63 studies.

Figure 1.

PRISMA Flow Diagram Showing Search Results

Figure 1 provides a PRISMA flow diagram showing search results.15

The 63 studies were mainly from the United States, China, Europe, and Australia. Included studies were also conducted in India, Malaysia, Korea, Thailand, Israel, Iran, and Russia. A total of 61 studies were observational, and 2 studies reported on interventions. Of the 61 observational studies, 43 studies were cross-sectional only, 6 were longitudinal only, and 12 reported both cross-sectional and longitudinal findings. One study was a retrospective study after a pandemic. In cross-sectional studies, likely confounders (eg, adversity, socioeconomic status [SES]) were rarely controlled for, meaning that the association between loneliness and mental health outcomes in these studies is very likely to be inflated.16 Four longitudinal studies used multi-informant approaches, including self-report and parent and/or teacher report to assess mental health outcomes. Importantly, they typically assessed and controlled for confounds and could assess the most plausible direction of causality between loneliness/social isolation and mental health.

Impact of Loneliness on Mental Health

Table 2 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60 and Table 3 61, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67, 68, 69, 70, 71, 72, 73, 74, 75, 76, 77, 78, 79 describe the 60 studies that examined the impact of loneliness on mental health. A total of 53 studies stated that they measured the impact of loneliness on mental health. Seven studies stated that they measured the impact of social isolation39 , 45 , 50 , 59 , 69 , 70 , 72 on mental health, but the social isolation measures used were either subscales or questions from loneliness scales, or strongly overlapped with the construct of loneliness. Therefore, we have considered them together with studies that measured loneliness. Participants were mainly school or university students or taking part in longitudinal cohort studies.

Table 2.

Cross-Sectional Studies Examining Social Isolation/Loneliness

| Authors (year), country |

Sample |

Total N (% male participants) |

Child (≤11 y)/adolescent (12−18 y)/Young adult (≥19 y) |

Age range at baseline y, |

Mean age (SD) |

Social isolation/ loneliness measure |

Mental health measure |

Associations between social isolation/loneliness and mental health [r (p)] unless otherwise stated |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depression |

Anxiety |

Other mental health |

||||||||

| Social isolation/loneliness and concurrent mental health symptoms | ||||||||||

| Alpaslan et al. (2016),17 Turkey | School students | 487 (41.7) | Adolescent | 14–19 | 16.07 (1.05) | UCLA Loneliness Scale | CDI, SDQ |

Male participants: OR 1.21 Female participants: OR 1.05 |

||

| Arslan (2020),18 Turkey | School students | 244 (47.5) | Adolescent | 14–18 | 16.27 (1.02) | 8-item UCLA Loneliness Scale-Short Form | Youth Internalizing and Externalizing behavior screeners | Lon - mental health problems 0.41 (<.001), β = 0.22 (<.01). | ||

| Baskin et al (2010),19 USA |

School students | 294 (NS) | Adolescent | NS Estimated 13-14 | 13.11 (0.469) | Children’s Loneliness Scale (CLS) | BDI-Y | R2 = .28 (<.001). Moderated by belongingness | ||

| Brage et al. (1993),20 Brage et al. (1995),21 USA | School students | 156 (39.7) | Adolescent | 11–18 | 14 (1.56) | Loneliness Inventory Short Form | CES-D (child version) | 0.646, (<.001) | ||

| Chang et al. (2017),22 USA |

University students | 228 (23.7) | Young adult | 18–28 | 19.69 (1.38) | Revised UCLA Loneliness scale | BDI, Frequency of Suicidal Ideation Inventory | 0.69 (<.001). Regressions: 47% shared variance |

Lon - suicidal ideation 0.52 (<.001). Lon R2 = 26.9% variance in suicidal ideation |

|

| Doman and Le Roux (2012),23 South Africa | University students | 275 (42.3) | Young adult | 19–34 | 20.92 (NS) | Le Roux Loneliness Questionnaire | Psychological General Well-Being Index: anxiety + depressed mood | 0.517 (<.01). 26.7% shared variance. |

Anx: 0.365, (<.01) | |

| Erdur-Baker and Bugay (2011),24 Turkey | School students | 144 (54.2) | Adolescent | 11–15 | 12.5 (1.61) | LSDQ | CDI | 0.51 (NS) | ||

| Ginter et al. (1996),25 Israel | School students | 144 (45.1) | Adolescent | 11–16 | 13.90 (1.5) | The Loneliness Rating Scale (subscales for Frequency, Intensity, Duration) + additional 2 questions | Revised Children's Manifest Anxiety Scale (RCMAS) | Not lonely group: Frequency of Lon-Anx 0.33 (<.001), Intensity of Lon- Anx 0.18 (< .05) Lon group > Anx t = 3.81 (<.001), |

||

| Heredia et al. (2017),26 USA |

School students | 394 (50.2) | Adolescent | 12–15 | 13.52 (0.63) | LSDQ | Well-being - World Health Organisation Well-being Index (WHO-5) | Lon−well-being 0.111, (<.05) Hierarchical linear regression: loneliness accounted for 1.3% of variance in well-being |

||

| Houghton et al (2016),27 Australia | School students | 1143 (46.3) | Adolescent | 10.1–16 | 13.20 (1.2) | Perth Aloneness Scale (includes (friendship-related loneliness subscale) | Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well Being Scale (WEMWBS) | Friendship related Lon−well-being 0.36 (< .001) | ||

| Hudson et al. (2000),28 USA |

Adolescent mothers post-partum recruited from primary health care practices | 21 (0) | Adolescent | 16–19 | 18 (1.14) | Revised UCLA Loneliness Scale | CES-D (child version) | 0.53 (<.05) | ||

| Hutcherson and Epkins (2009),29 USA |

Female school students (and their mothers) | 100 (0) | Child | 9–12 | 10.52 (1.04) | Loneliness Scale (LS) | Social Anxiety Scale for Children-Revised (SASC-R), CDI | 0.62 (<.001). Controlling for social Anx 0.36 (<.001) |

Social anx: 0.65 (<.001) Controlling for Dep 0.49 (<001) | |

| Jackson and Cochran (1991),30 USA |

University students | 293 (49.8) | Young adult | 17–26 | Median 19 | Revised UCLA Loneliness Scale | Symptom Checklist-90 (SCL-90) | 0.54 (<.001). Controlling for overall symptoms 0.23 (<.01) |

General Anx: 0.37 (<.001) | Obsessive- compulsive disorder 0.40 (<.001) |

| Johnson et al (2001),31 USA |

University students | 124 (43.5) | Young adult | 17–21 | Male participants 19.41 (NS) Female participants 19.69 (NS) |

UCLA Loneliness Scale (Revised) | Franke and Hymel Social Anxiety and Social Avoidance Scale | Soc anx: F6,115 = 4.23 (<.05) β = 0.24 (<.01) R2 = 0.31 (<.01) |

||

| Kim (2001),32Korea | University students | 452 (44.7) | Young adult | 18–25 | 20.9 (2.0) | Revised UCLA Loneliness Scale | BDI | Male participants: β = 0.49 (<.01). 24% shared variance | ||

| Koenig et al. (1994),33USA | School students | 397 (38.3) | Adolescent | 14–18 | NS | Revised UCLA Loneliness Scale | BDI | Male participants: 0.55 (<.001) Female participants: 0.49 (<.001) |

||

| Lasgaard, Goosens et al. (2011),34Denmark | School students | 1009 (43) | Adolescent | NS | 17.11 (1.11) | SELSA–SF (3 subscales: social lon, family-related lon, romantic lon) | BAI-Y, BDI-Y, Social Interaction Anxiety Scale (SIAS), Suicide Ideation subscale from the Suicide Probability Scale, Deliberate self-harm (DSH), Risk Behavior related to Eating Disorders (RiBED-8) |

23% of the variance Peer-related lon – Dep β= 0.26, r2 = 0.076; family-related lon – Dep β = 0.29, r2 = 0.089 | Anx: 14% shared variance Peer-related Lon β = .21 r2 = .045. Family- related Lon β = .21 r2 = .045 Social Anx: 21% shared variance. Peer-related Lon β = .33 r2 = .109. Romantic Lon β = 0.19 r2 = 0.040. |

Suicidal ideation (SI): 14% shared variance. Peer-related Lon – SI β = 0.17, r2 = 0.027. Family-related Lon – SI β = 0.26, r2 = .061 Self-harm: 10% shared variance. Family-related Lon β = 0.31, r2 = 0.081. Eating disorder (ED): risk behavior: 6% shared variance Family related lon – ED β = .22, r2 = .041 |

| Lau et al. (1999),35Hong Kong | School students | 6,356 (NS estimated 48) | Child/adolescent | 9–14 | NS | Marcoen and Brumagne’s Loneliness Scale (3 subscales: Peer-Related Lon, Parent-Related Lon, and Aloneness) |

CDI, RCADS |

Primary school students: 0.71 (<.001) Peer-related Lon 0.67 (<.001), parent-related Lon 0.49 (<.001), aloneness – 0.65 (<.001). 46% shared variance Secondary school students: 0.81 (<.001) Peer-related Lon 0.77, (<.001), parent-related Lon 0.56 (<.001), aloneness – Dep 0.72 (<.001) 65% shared variance |

||

| Majd Ara et al. (2017),36 Iran | Female school students | 301 (0) | Adolescent | 15–18 | 16.6 (1.1) | Children’s Loneliness Scale | DASS-21 | 0.66 (NS). | ||

| Mahon et al. (2001),37USA | School students | 127 (43.3) | Adolescent | 12–14 | 12.9 (0.63) | Revised UCLA Loneliness Scale | Profile of Mood States - Depression- Dejection subscale | 0.57 (<.001). | ||

| Markovic and Bowker (2015),38 USA |

School students | 157 (45) | Adolescent | NS | 13.84 (.75) | LSDQ | YSR | 0.39 (<.001) | Anx: 0.35 (<.001) | |

| Matthews et al. (2016),39 UK |

Twin birth cohort | 2066 (49) | Young adult | 18 | 18.4 (0.36) | Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS) | Diagnostic Interview Schedule | 0.21 (<.001) | ||

| McIntyre et al. (2018), UK | University students | 1135 | Young adult | NS | 20.78 (4.35) | UCLA Loneliness Scale | PHQ-9, GAD=-7, Self-harm (4 items) |

0.58 (<.001) β = 0.52 (<.001) |

Anx: 0.54 (<.001) β = 0.50 (<.001) |

|

| Moore and Schultz (1983),41USA | School students | 99 (45) | Adolescent | 14–19 | 17 (0.98) | UCLA Loneliness Scale (ULS) + frequency, duration, characteristics and perceived causes of loneliness | SDS, STAI |

0.66 (<.001). Lon duration 0.46, (<.001) Lon frequency -Dep 0.70 (<.001) |

State anx: 0.48 (<.001) Lon duration 0.37 (<.001) Lon frequency 0.48 (<.001) |

|

| Mounts et al. (2006),42 USA |

University students – ethnically diverse sample | 350 (36) | Young adult | 18–19 | NS | Revised UCLA Loneliness Scale | BDI, BAI |

β = 0.51, (<.001) | Anx β = 0.30 (<.001) |

|

| Neto and Barros (2000),43 Portugal | School students | 487 (39.3) | Adolescent | NS (estimated 15–18) | Cape Verde 17.5 (1.2): Portugal 17.8 (1.0). | Revised UCLA Loneliness Scale | Social Anxiety subscale | Social Anx 0.33−0.35 (<.001) | ||

| Purwono and French (2016),44 Indonesia |

Muslim school students | 453 (45.9) | Adolescent | 13–16 | 7th grade: 13.57 (0.44) 10th grade: 16.47 (0.43) |

10 items from UCLA Loneliness Scale - modified | CES-D | 0.59 (<.01). | ||

| Richardson et al. (2019),45 Australia | Community | 528 (51) | Child/Adolescent | 10−12 | 11.18 (0.56) | 3 Items from School Belonging and Isolation Scale | SCAS-C– subscales generalized anx, social Anx and separation Anx 3 item SMFQ | 0.46 (<.001). | Social Anx 0.50 (<.001). Generalized Anx 0.42 (<.001) Separation anx 0.41 (<.001) |

|

| Roberts and Chen (1995),46USA | School students | 2614 (n.s) | Adolescent | 11–14 | NS (NS) | 8 item UCLA Loneliness Scale | CES-D, 4 suicide items from Oregan Adolescent Depression Project |

OR = 5.8 (<.001) | Suicidal ideation: OR 5.0 | |

| Singhvi et al. (2011),47India | School students | 300 (50) | Adolescent | 15–17 | NS | Revised UCLA Loneliness Scale | SDS, Cohen’s Perceived Stress Scale |

Male participants: 0.461(<.001) Female participants: 0.683 (<.001) Male participants: Lon associated with Dep t = 6.32 (<.005) β = 0.461 Female participants: Lon associated with Dep t = 11.38 (<.005) β = 0.683 |

Male participants: Lon associated with perceived stress [t=1.50, p<.01, β=-.108] | |

| Spithoven et al. (2017),48 Belgium and Netherlands | NS | Sample 1: 417 (48.4) Sample 2: 1140 (48.7) |

Adolescent | NS | Sample 1: 12.47 (1.89) Sample 2: 12.81 (0.42). |

LACA – peer-related loneliness subscale | Sample 1: CDI. Sample 2: Iowa short form of CES-D. |

Sample 1: 0.48 (<.001) Sample 2: 0.54 (<.001) |

||

| Stednitz and Epkins (2006),49 USA |

Community sample | 102 (0) | Child | 9–12 | 10.46 (1) | LSDQ | CDI, Social Anxiety Scale for Children – Revised (child and parent versions) |

0.63 (<.001) | Social anx: self-rated 0.72 (<.001). Mother-rated 0.36 (<.001) |

|

| Stacciarini et al. (2015),50 USA |

Church and community (Latina/o immigrants) | 31 (42) | Adolescent | 11–18 | 13.0 (2.0) | Short version of PROMIS Health Organisation Social Isolation | SF-12 Health survey | Mental health r = −0.38 (<.05) | ||

| Stickley et al. (2016),51 Czech, Russia and USA |

School students | Sample 1: 2205 (NS) Sample 2: 1995 (NS) Sample 3: 2050 (NS) |

Adolescent | 13–15 | NS | Lon item from CES-D | CES-D (minus Lon item), 12 statement anxiety scale |

ORs: 8.04−40.13 | Anx: ORs: 1.63−5.49 | |

| Swami et al. (2007),52Malaysia | University students | 172 (41.8) | Young adult | 18–24 | 20.3 (1.25) | Revised UCLA Loneliness Scale | BDI | 0.38 (<0.01). | ||

| Thomas and Bowker (2015),53USA | School students | 103 (51.4) | Child/Adolescent | NS (estimated 10-13) | 13.73 (0.82) | LSDQ | YSR | 0.42 (<0.1) | ||

| Tu and Zhang (2014),54 China |

University students | 444 (38.4) | Young adult | NS | 19.02 (1.26) | Revised UCLA Loneliness Scale | CES-D (7 item version), Perceived Stress Scale | γ = 0.517 (<.001) β = 0.833 (<.001) |

Stress: γ = 0.381 (<.001) β = 0.297 (<.001) |

|

| Uba et al. (2012),55 Malaysia |

School students | 242 (49.2) | Adolescent | 13–16 | 14.67 (1.27) | Revised UCLA Loneliness Scale | CDI | 0.493 (<.01) | ||

| Vanhalst, Luyckx, Raes (2012),56 Belgium |

University students | 370 (16.5) | Young adult | NS | 18.22 (1.21) | LACA | CES-D | Peer-related Lon 0.58 (.001) Parent-related Lon 0.23 (<.001) | ||

| Wang and Yao (2020),57 China | Schools (left behind children in rural China) | 442 (54) | Child/Adolescent | 8–16 | 11.5 (2.098) | UCLA Loneliness Scale | Social Anxiety Subscale | Social Anx: 0.332 (<.001) | ||

| Xu and Chen (2019),58 China |

School students | 724 (59.5) | Child/Adolescent | 6–14 | 9.15 (1.79) | LSDQ | CES-D | 0.492 (<.01) | ||

| Yadegarfard et al. (2014),59 Thailand |

Transgender association and university (male transgender and cis gender) | 260 (100) | Adolescent/Young adult | 15–25 | 20 (NS) | SSA | DASS-21 (short version), Positive and Negative Suicide Inventory | Transgender: Social support−Dep (B = −0.01) Lower social support associated with higher negative risk factors related to suicidal behavior (B = 0.13) Cisgender: Social support−Dep (B = 0.23) Lower social support associated with higher negative risk factors related to suicidal behavior (B = 0.15) |

||

| Social Isolation/Quarantine in the Context of Infectious Disease | ||||||||||

| Sprang and Silman (2013),60 USA, Canada, and Mexico |

Parents of children (who experienced H1N1/SARS/ avian flu pandemics) | 398 (NS) | Child | NS | NS | Children experienced pandemic; 20.9% social isolation and 3.8% quarantine | PTSD-RI; PCL-C | PTSD-RI: Children who experienced isolation/quarantine were more likely to meet cut-off score for PTSD (30%) than those who had not been in isolation or quarantine; 1.1%; χ2 = 49.56 (<.001), Cramer V = 0.449 Mean scores in isolated/quarantined group (22.3) were 4 times those in general group (5.5); t = 6.59 (.000) PCL-CL: Children who experienced isolation/quarantine were more likely to meet cut-off score for PTSD (28%); χ2 = 31.44 (<.001) |

||

Note: Anx = Anxiety; BAI = Beck Anxiety Inventory; BAI-Y = Beck Anxiety Inventory for Youth; BDI = Beck Depression Inventory; BDI-Y = Beck Depression Inventory for Youth; CBCL = Child Behaviour Checklist; CDI = Children’s Depression Inventory; CES-D = Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale; DASS-21 Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale, Dep = depression; GAD-7 = Generalized Anxiety Disorder – 7; Lon = Loneliness; LSDQ = Loneliness and Social Dissatisfaction Questionnaire; LACA = Loneliness and Aloneness Scale for Children and Adolescents; OR = Odds Ratio; PCL-C = PTSD Checklist Civilian Version; PHQ-9 = Patient Health Questionnaire; PTSD-RI = UCLA Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Reaction Index; RCADS = Revised Children’s Anxiety and Depression Scale; SAS-A = Social Anxiety Scale for Adolescents; SCAS-C = Spence Children’s Anxiety Scale- Child; SDS = Zung Self-rating Depression Scale; SDQ = Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire; SELSA = Social and Emotional Loneliness Scale for Adults; SMFQ = Short Mood and Feelings Questionnaire-Child; SSA = Social Support Appraisals scale; STAI = State Trait Anxiety Inventory; TRF = Teacher Rating Form; YSR = Youth Self-Report Form.

Table 3.

Longitudinal Studies Examining Social Isolation/Loneliness and Subsequent Mental Health Outcomes

| Author (year), country | Sample (selection criteria) | Total N (% male participants) | Child (≤11 y)/adolescent (12−18 y)/young adult (≥19 y) | Age range, y | Mean age (SD) at T1 | Social isolation/ loneliness measure | Mental health measures | Cross-Sectional associations r (p) | Length of follow-up, y | Is social isolation/loneliness associated with later mental health? |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depression | Anxiety | ||||||||||

| Boivin et al. (1995),61 Canada |

School students | 774 (51.8) | Child | 9–12 | 10.8 (NS) | LSDQ | CDI | Lon-Dep 0.53 (p < .001) | 1 | T1 Lon – T2 Dep: r = 0.36 (p < .01) T1 Lon accounted for 8.3% of variance in T2 Dep |

|

| Christ et al. (2017),62 USA |

National Survey of Child and Adolescent Well-being (child welfare cohort) | 2776 (47) | Adolescent | 11–17 | 13.5 (NS) | LDSQ 7 peer isolation items | 4 items from YSR | NS | 7 | Controlling for caregiver neglect and covariates, a 1-SD increase in peer isolation was associated with a 0.49-SD increase in depression | |

| Danneel et al. (2019),63 Belgium |

Longitudinal cohorts | Sample 1: 1116 (51.1), Sample 2: 1423 (47.6), Sample 3: 549 (37.33) |

Adolescent | Sample 1: 11–17 Sample 2: 11–18 Sample 3: 12–17 |

Sample 1: 13.79 (0.94) Sample 2: 13.59 (0.98) Sample 3: 14.82 (0.79) |

LACA peer-related loneliness subscale | Samples 1 and 3 – SAS-A; CES-D. Sample 2 - CDI |

Lon-Social anxiety 0.58 ≤ r ≤ 0.67 Lon-Dep 0.48 ≤ r ≤ 0.56 (all <.01) |

1 | Not significant | Lon → Social anxiety β = 0.10 (p < .001) |

| Fontaine et al. (2009),64 USA |

School students (longitudinal cohort) | NS (52) | Child | NS Estimated 5–9 | NS | LSDQ (T2) | Internalizing items from: CBCL (mother T1 and T3); TRF (teacher T1 and T2); YSR (self T2 and T3) |

NS | 2-3 | T2 Lon → Anx/Dep symptoms at T3 γ2 = 0.18, z = 2.60 (p < .01) |

|

| Jones et al. (2011),65 USA |

Longitudinal cohort | 889 (50) | Child | 6 | NS | LSDQ | CDI short form | NS | 9 | Indirect effects T1 Lon → T2 Suicidal thoughts through Dep (β = 0.06, p < .001) | |

| Ladd and Ettekal (2013),66 USA |

School students (longitudinal cohort) | 478 (50) | Adolescent | 12–18 | 12.0 (n.s) | LSDQ – revised - 3 items | Depression items CBCL (parent); TRF (teacher); YSR (self) |

Lon-Dep 0.19 (p < .01) (parent), 0.38 (p < .001) (teacher) 0.62 (p < .001) (self) |

7 | Changes in Lon associated with changes in Dep reported by teachers (r = 0.63, p < .001) and adolescents (r = 0.65, p < .001), but not parents (r = 0.18,p = .13) |

|

| Lalayants and Prince (2015),67 multiple countries | National Survey of Child and Adolescent Wellbeing (child welfare cohort) | 356 (0) | Adolescent | 11–12 | NS | LSDQ | CDI | NS | 1.5 | T1 Lon → T2 Dep AOR = 2.93, CI = 1.74−4.91 (p < .001) T1 lonely female participants were 5.09 times more likely (CI 2.24−11.56 (p < .001) to be depressed at T2 |

|

| Lapierre et al. (2019),68 USA |

College Students | 346 (33.6) | Young adult | 17–20 | 19.11 (0.75) | UCLA Loneliness Scale | 10-Item CES-D | Lon-Dep 0.628 (T1), 0.666 (T2) (p < .001) | 0.25 | T1 Lon – T2 Dep (r = 0.524, p < .001) T1 Lon → T2 Dep b = 0.21, SE = .05 (p < .001) |

|

| Lasgaard et al. (2011b),69 Denmark | School students | T1: 1009 (43) T2: 541 (40) |

Adolescent/Young adult | 15–26 | 17.11 (1.11) | SELSA-short form; MSPSS | BAI-Y, BDI-Y |

Lon-Dep 0.61 (p < .0005) Lon-Anx 0.51 (p < .0005). Soc support– Dep r = −0.12, −0.18, −0.28 (all p < .0005) |

1 | T1 Lon→ T2 Dep (r = 0.37, p < .0005) Cross-lagged structural equation modeling found T1 Lon did not predict Dep at T2 |

|

| Liu et al. (2020),70 China |

College students | 741 (28.3) | Young adult | NS (estimated 18−20) | 18.47 (0.87) | 6 item index of social isolation based on only child status, number of friends, frequency of contact with friends and family; UCLA Loneliness Scale | SDS | NS | 3 | Female participants: T1 isolation associated with increased Dep (β = 0.22, p < .001) Lon associated with increased Dep (β = 0.23, p < .001) Male participants: T1 isolation associated with increased Dep (β = 0.25, p < .01) Lon did not predict Dep (β = 0.14, p > .05) |

|

| Mak et al. (2018),71 USA |

School students (randomized trial) | 687 (47.7) | Adolescent | NS (estimated 11–14) | 11.27 (0.49) | LSDQ | SAS-A | Lon-social anxiety 0.41−0.45 (p < .01) | 1.5 (T2), 3 (T3) | T1 Lon → T2 Social Anxiety (β = 0.09, p < .05). T2 Lon → T3 Social Anxiety (β = 0.12, p < .01) By gender: T2 Lon → T3 Social Anx: Boys (β = 0.22, p < .001) Girls (β = 0.01 p = .79) |

|

| Matthews et al. (2015),72 UK |

Twin birth cohort | 2232 (NS) | Child | 5 | NS | 6 items from CBCL (parent) and TRF (teacher) | MASC | NS | 7 | T1 social isolation failed to predict T2 Anx, controlling for T1 Anx | |

| Qualter et al. (2010),73 UK |

School students | 296 (49.3) | Child | 5 | NS | T1 and T2: Peer and Parent subscales LACA | T1: T-CARS T2 and T3: DDPCA |

T1 Peer Lon-internalizing symptoms 0.32 (p < .01) Parent Lon-Internalizing Symptoms 0.09. T2 Peer Lon- Dep 0.13 (p < .05) Parent Lon-Dep 0.12 (p < .05) |

8 | T1 Peer Lon-T2 Dep r = 0.07 T1 Peer Lon-T3 Dep r = 0.06 T2 Peer Lon – T3 Dep r = 0.12 (p < .05) T1 Parent Lon – T2 Dep r = 0.19, p < .01 T1 Parent Lon-T3 Dep r = 0.13 (p < .05) T2 Parent Lon-T3 Dep r = 0.08 Structural model: Duration of Peer Lon → T3 Dep T1 and T2 Peer Lon, Parent Lon (T1, T2, and duration) did not independently predict T3 Dep |

|

| Schinka et al. (2013),74 USA |

Longitudinal cohort study | 832 (53) | Child | 9 | NS | LDSQ | T1: CBCL (mother) T3: CDI−Short form; Suicide items from CBCL and YSR |

T3 Lon-Dep -0.10 (p < .01) Lon− suicidal ideation r = 0.02 Lon− suicide attempt r = 0.4 |

2 (T2), 6 (T3) |

T1 Lon-T3 Dep r = 0.01 T2 Lon-T3 Dep r = −0.01 T1 Lon-T3 Suicidal ideation r = 0.00 T2 Lon-T3 suicidal ideation r = 0.03 T1 Lon-T3 suicide attempt r = 0.02 T2 Lon-T3 suicide attempt r = −0.01 |

|

| Vanhalst, Goosens et al. (2013)75 and Vanhalst, Klimstra et al. (2012),76 Netherlands | Community sample via municipality registers | 389 (53) | Adolescents | 15 | 15.22 (0.60) | LACA Peer-related loneliness subscale | 6 item depression questionnaire; SCARED generalized anxiety, panic and social anxiety subscales. | Lon-Dep 0.34−0.50 (p < .001) Lon- Perceived stress 0.23 (p < .001). Lon- Generalized Anx 0.40 (p < .001), Lon-Panic 0.13 (p < .05), Lon− Social phobia 0.47 (p < .001) |

5 | T1 Lon → T2 Dep symptoms (B = 0.13, p < .001) | |

| Vanhalst, Luyckx et al. (2012)77 Belgium | University students | Sample 1: 514 (10.9) Sample 2: 437 (17) |

Young adults | Sample: 19.62 (0.62) Sample 2: 18.22 (1.21) |

NS | Sample 1: 8-item revised UCLA Loneliness Scale. Sample 2: LACA Peer-related loneliness subscale |

Sample 1: 12-item CES-D Sample 2: 20-item CES-D |

Sample 1: Lon-Dep 0.49−0.52 (p < .001) Sample 2: Lon-Dep r = 0.40−0.60 (p < .001) |

2 | Sample 1: T1 lon – T2 Dep r = 0.35 (p < .001) T1 lon – T3 Dep r = 0.36 (p < .001) Lon → associated with Dep across both time intervals. Sample 2: cross-lagged path from Lon associated with Dep (b = 0.12, p < .05) |

|

| Wang et al. (2020),78 China |

School students | 921 (48.3) | Adolescents | 12–15 | 12.98 (0.66) | Revised UCLA Loneliness Scale (T1 and T2) | SCARED; DSRSC (T1 and T3) |

T1 Lon- Anx 0.40 (p < .001) Lon-Dep 0.57 (p < .001) |

1 | T1 Lon-T3 Dep 0.36 (p < .001) T2 Lon-T3 Dep 0.46 (p < .001) |

T1 Lon-T3 Anx 0.29, p<.001. T2 Lon-T3 Anx 0.36 (p < .001) |

| Zhou et al. (2020),79 China | School students | 866 (49) | Adolescents | 11–15 | 12.98 (0.67) | UCLA Loneliness Scale (T1 and T2) | DSRSC (T3) | T1 Lon-Dep r = 0.56 (p < .001) |

2 | T1 Lon-T3 Dep r = 0.38 (p < .001) Controlling for age, sex, and SES, T2 Lon-T3 Dep adjusted b = 0.34 (p < .001) |

|

Note: Anx = Anxiety; BAI-Y = Beck Anxiety Inventory for Youth; BDI-Y = Beck Depression Inventory for Youth; CBCL = Child Behaviour Checklist; CDI = Children’s Depression Inventory; CES-D = Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale; DDPCA = Depression Profile for Children and Adolescents; Dep = depression; DSRSC = Birleson Depression Self-Rating Scale for Children; Lon = Loneliness; LSDQ = Loneliness and Social Dissatisfaction Questionnaire; LACA = Loneliness and Aloneness Scale for Children and Adolescents; MASC = Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children; MSPSS = Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support; NS = not specified; SAS-A = Social Anxiety Scale for Adolescents; SCARED = Scale for Child Anxiety Related Emotional Disorders; SES = socioeconomic status; SDS = Zung Self-rating Depression Scale; SELSA = Social and Emotional Loneliness Scale for Adults; T-CARS = Teacher-Classroom Adjustment Rating Scale; T1 = Time 1; T2 = Time 2; T3 = Time 3; TRF = Teacher Rating Form; YSR = Youth Self-Report Form.

A total of 45 studies examined the cross-sectional relationship between depressive symptoms and loneliness and/or social isolation.17 , 19 , 20, 21, 22, 23, 24 , 28, 29, 30 , 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38 , 40, 41, 42 , 44 , 46, 47, 48, 49 , 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56 , 58 , 61 , 63 , 66 , 68 , 73, 74, 75, 76, 77, 78, 79 The majority were conducted in adolescent (N = 23) and young adult (N = 16) samples, although 6 studies included children under the age of 10 years. Most reported moderate to large correlations (0.12 ≤ r ≤ 0.81), and most included a measure of depressive symptoms. Two studies reported odds ratios, with those who were lonely 5.846 to 40 times51 more likely to score above clinical cut-offs for depression. The associations were stronger in older participants35 and in female participants.47 However, the strength and direction of the associations did not differ by age of the sample. Fewer studies (N = 23) examined symptoms of anxiety. Those that did found small to moderate associations between anxiety and loneliness/social isolation (0.18 ≤ r ≤ 0.54). The duration of loneliness was more strongly associated with anxiety than intensity of loneliness.25 , 41 Social anxiety was moderately to strongly associated with loneliness/social isolation (0.33 ≤ r ≤ 0.72) and there were moderate associations between generalized anxiety and loneliness/social isolation (r = 0.37, 0.40).45 , 30 One study found a small association between panic and loneliness (r = 0.13).75 , 76 In the single study that reported odds ratios, being lonely was associated with increased odds of being anxious by 1.63 to 5.49 times.51 Positive associations were also reported between social isolation/loneliness and suicidal ideation,20 , 21 , 34 self-harm,34 and eating disorder risk behavior.34 Negative associations were reported between social isolation/loneliness and well-being26 , 27 and mental health.50

Eighteen studies followed participants over time (Table 3).61 , 62 , 64 , 65 , 67, 68, 69, 70, 71, 72 , 74, 75, 76, 77 , 79 , 80 Several of these were conducted in childhood (N = 6), or adolescence (N = 8), although three were in university students. Most (N = 12) had only one follow up time point, usually between 1 and 3 years.

In all, 12 of the 15 studies found that loneliness is associated with depression and explained a significant amount of the variance in severity of depression symptoms several months to several years later.61 , 62 , 64 , 65 , 67, 68, 69, 70, 71, 72 , 74, 75, 76, 77 , 79 , 80 Two studies found that loneliness in childhood at age 5 years was not associated with depression several years later,73 , 74 although other studies that assessed loneliness during childhood found evidence that it is associated with subsequent depression.61 , 64 One large study of adolescents (n = 3,088) found that loneliness was not associated with depression 1 year later.63 There were mixed findings in another large study of adolescents (n = 541), which found a significant association between loneliness and subsequent depression, although this did not hold in a cross-lagged model,69 suggesting a possible bidirectional relationship between the variables. A study of university students found evidence of a sex difference, with loneliness being associated with later depression in female participants but not in male participants.70 In a large longitudinal cohort of vulnerable young people, aged 11 to 17 years, after controlling for caregiver neglect and other relevant covariates, a substantial increase in self-reported peer isolation (1 SD) was associated with an increase in depression symptoms (0.49 SD).62 Duration of peer loneliness rather than intensity of peer loneliness was associated with depression 8 years later (ie, from age 5 to age 13 years); in contrast, family-related loneliness was not independently associated with subsequent depression.73

Three of the four studies that examined the longitudinal effect of loneliness on anxiety found that loneliness was associated with later anxiety.63 , 71 , 78 Two of these studies assessed social anxiety, and one measured anxiety as a broad construct. One study did not find that loneliness/social isolation at age 5 years was associated with anxiety at age 12 years.72 One study of young adolescents found differences by sex, with loneliness being associated with later social anxiety in male participants but not female participants.71 None of these studies measured loneliness during childhood.

Other mental health outcomes reported over time included internalizing symptoms which were associated with prior loneliness in primary school age children,64 and suicidal ideation during adolescence, which was not associated with prior loneliness during childhood.74

Impact of Social Isolation in an Infectious Disease Context

One study60 reported on mental health and social isolation in the context of different infections, including H1N1, severe acute respiratory syndrome, and avian flu (Table 2). This retrospective study included 398 parents of exposed children from the United States, Canada, and Mexico, of whom 20.9% experienced social isolation and a further 3.8% had been quarantined. Parents of children reported on their child’s experience of trauma and on their current mental health. One-third of parents whose children had been subjected to disease containment measures said that their child had needed mental health service input because of their pandemic-related experiences. The most frequently reported diagnoses were acute stress disorder (16.7%), adjustment disorder (16.7%), grief (16.7%), and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (6.2%). Two different parent-reported measures of PTSD symptoms found that those children exposed to disease containment measures scored significantly higher for PTSD symptoms postpandemic. On the PTSD Checklist Civilian Version, 28% of children who had experienced isolation/quarantine scored about the cut-off for PTSD, compared to 5.8% of those who had not experienced isolation/quarantine. Similarly, on the UCLA PTSD Reaction Index, 30% of children who experienced isolation/quarantine scored above the cut-off for PTSD, compared to 1.1% of those who had not experienced isolation/quarantine (effect size: Cramer V = 0.449). Mean scores were four times higher in the isolated/quarantined group than in those who had not been isolated/quarantined. The most common trauma symptoms in the quarantined/isolated group were avoidance/numbing (57.8%), re-experiencing (57.8%), and arousal (62.5%).

Interventions

Two randomized controlled trials measured loneliness and mental health outcomes following an intervention aimed at the general population (peer mentoring81 and classroom based82 (Table 4 ). In both instances, the comparator was no intervention/with follow-up and education as usual. A relatively intensive peer mentor program, with an adult mentor, 4 to 6 hours per month for 4 months on average, reduced loneliness and mental health problems (small to medium effects) for victims of bullying and victimization. However, a brief (two-session) universal classroom-based program delivered in schools including psychosocial support through peer mentors and a staff mental health support team did not reduce loneliness. Neither intervention specifically addressed mental health problems that had developed in the context of loneliness; therefore, we are unable to answer our second review question, which was what interventions are effective for individuals who have developed mental health problems as a result of social isolation or loneliness.

Table 4.

Study Description and Relevant Findings: Intervention Studies

| Author (year), country | Sample | Total N (% male participants) | Age range at baseline, y | Mean age (SD) | Loneliness measure | Mental health measures | Intervention | Comparison condition | Main findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| King et al. (2018),81 USA |

Experienced bullying/Victimization, recruited via paediatric medical emergency services | 218 (33. 5) | 12–15 | 13. 50 (1. 1) | Revised UCLA Loneliness Scale | Reynolds Adolescent Depression Scale−2 short; Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale | LET’S CONNECT (LC) mentorship program (strengths-based approach) Mentorship lasted an average of 120.32 days (SD = 69.69), 4−6 h/mo | No treatment | At 6 months, loneliness decreased more in LC intervention group than in control group (p < . 01) ES = 0.4 |

| Larsen et al. (2019), 82 Norway |

School students | 2,254 (NS; estimate 53). | 15–19 | 16. 82 (NS) | Loneliness Scale (modified) | Symptom Checklist | Dream School Program; aimed to change psychosocial environment of classroom, including through peer mentors and a staff mental health support team. Two classes over two semesters | Education as usual. | No significant effects on mental health or loneliness for either intervention group |

Note: ES = effect size; NS = not specified.

Discussion

This rapid systematic review of 63 studies of 51,576 participants found a clear association between loneliness and mental health problems in children and adolescents. Loneliness was associated with future mental health problems up to 9 years later. The strongest association was with depression. These findings were consistent across studies of children, adolescents, and young adults. There may also be sex differences, with some research indicating that loneliness was more strongly associated with elevated depression symptoms in girls and with elevated social anxiety in boys.70 , 71 The length of loneliness appears to be a predictor of future mental health problems.73 This is of particular relevance in the COVID-19 context, as politicians in different countries consider the length of time that schools should remain closed, and the implementation of social distancing within schools.

Furthermore, in the one study that examined mental health problems after enforced isolation and quarantine in previous pandemics, children who had experienced enforced isolation or quarantine were five times more likely to require mental health service input and experienced higher levels of posttraumatic stress. This suggests that the current social distancing measures enforced on children because of COVID-19 could lead to an increase in mental health problems, as well as possible posttraumatic stress. These results are consistent with preliminary unpublished data emerging from China during the COVID-19 pandemic, where children and adolescents aged 3 to 18 years are commonly displaying behavioral manifestations of anxiety, including clinginess, distraction, fear of asking questions about the pandemic, and irritability.83 Furthermore, a large survey of young adult students in China has reported that around one in four are experiencing at least mild anxiety symptoms.84 In the United Kingdom, early results from the Co-SPACE (COVID-19 Supporting Parents, Adolescents and Children in Epidemics) online survey of more than 1,500 parents suggest high levels of COVID-19−related worries and fears, with younger children (aged 4−10 years) significantly more worried than older children and adolescents (aged 11−16 years).85 , 86

In addition to the more direct effects of enforced isolation and quarantine, loneliness as an unintended consequence of disease containment measures seems to be particularly problematic for young people.5 , 7 This may be because of the particular importance of the peer group for identity and support during this developmental stage.87 , 88 This propensity to experience loneliness may make young people particularly vulnerable to loneliness in the COVID-19 context, which, based on our findings, may further exacerbate the mental health impacts of the disease containment measures. More studies have examined the relationship between loneliness and depression than between loneliness and anxiety. Losing links to other people and feeling excluded can result in an affective response of depression.89 Social anxiety was more strongly associated with loneliness than other anxiety subtypes. This may be because social anxiety is triggered by a perceived threat to social relationships or status.90

It is difficult to predict the effect that COVID-19 will have on the mental health of children and young people. The subjective social isolation experienced by study participants did not mirror the current features of social isolation experienced by many children and adolescents worldwide. Social isolation was not enforced upon the participants, nor was social isolation almost ubiquitous across their peer groups and across the communities in which they lived. As loneliness involves social comparison,91 it is possible that the shared experience of social isolation imposed by disease containment measures may mitigate the negative effects. The studies were also not in the context of an uncertain but dangerous threat to health. These features limit the extent to which we can extrapolate from existing evidence to the current context. To make evidence-based decisions on how to mitigate the impact of a second wave, we need further research on the mental health impacts of social isolation in the disease containment context of a global pandemic. In this context, to more specifically understand the impacts of loneliness, measures such as the Loneliness and Aloneness Scale for Children and Adolescents (LACA) that assess the duration and the intensity of loneliness, and that separate peer-related loneliness from parent-related loneliness could be elucidating.

This rapid systematic review was conducted rapidly, in 3 weeks, to inform our response to COVID-19. We double screened 20% of all articles and data extracted. In line with Cochrane rapid review guidance,10 gray literature, and trial registry databases were not searched, hand-search strategies were not used, and only English-language publications were included, meaning that some relevant studies may have been missed. During the rapid data extraction phase, there was no scope to contact authors to request any missing information. The main limitation of this review is the lack of high-quality studies investigating mental health problems after enforced isolation. All but one study investigated social isolation that was not enforced on young people and was not common across a peer group. The effect of widespread social distancing could mitigate against the social isolation described with increased use of Internet-mediated relationships, which can be beneficial to adolescents.92 Most studies were cross-sectional, and therefore the direction of the association cannot be inferred. Few studies used independent (ie, not self-report) measures of mental health or social isolation/loneliness, thereby increasing the risk of bias. Furthermore, the studies were mainly observational and did not consistently control for potential confounders. The majority of studies focused on depression and anxiety, and other mental health problems are important to measure in future research.

However, we used all available evidence on social isolation and loneliness to inform the likely outcome for healthy children and adolescents subjected to social isolation. The results were consistent across all study methodology for depression (but less so for anxiety), suggesting that these results are reliable. The results are also consistent with one study investigating mental health problems in children60 after pandemics, improving our confidence in the results. However, the postpandemic study has several limitations in that the sample was self-selecting, and the demographics of the children and the time elapsed since the experience were not reported. There is little evidence pertaining to interventions. We have focused on healthy populations in this review and will report on those with pre-existing conditions including mental health problems elsewhere.

Implications for Policy and Practice

The review indicates that loneliness is associated with adverse mental health in children and adolescents. There is limited evidence that indicates specific interventions to prevent loneliness or to reduce its effects on mental health and well-being. However, there are well-established practical and psychological strategies that may help to promote child and adolescent mental health in the context of involuntary social isolation, for example, during the COVID-19 pandemic. Reducing the impact of enforced physical distancing by maintaining the structure, quality, and quantity of social networks, and helping children and adolescents to experience social rewards, to feel part of a group, and to know that there are others to whom they can look for support is likely to be important.8 Finding ways to give children and adolescents a sense of belonging within the family and to feel that they are part of a wider community should be a priority. Therefore, providing accurate information about the relative risks and benefits of social media and networking to parents who overestimate the dangers of allowing their children too much screen time may help young people to access the benefits of virtual social contact.

However, simply increasing the frequency of contact may not address young people’s subjective experience of loneliness.39 Helping young people to identify valued alternative activities and build structure and purpose into periods of involuntary social isolation may help to provide a wider range of rewards.93 Addressing negative thoughts about social encounters (eg, self-blame, self-devaluation) may also be effective.30 , 94 During periods of prolonged social isolation, digital technology that provides evidence-based interventions to help young people to reappraise their thoughts and to change their behavior within the confines of the home setting may be particularly welcome.

Although this review did not provide evidence on interventions to improve social isolation or loneliness in healthy children and adolescents, given social distancing, digital interventions may be appropriate. A computerized self-help program that is based on cognitive−behavioral therapy (CBT), BRAVE-TA was shown to be effective for anxiety following the Christchurch earthquake in New Zealand.95 Furthermore, computerized CBT, such as MoodGym, SPARX, and “Think, Feel, Do” generally have small but positive effects on mental health.96 , 97 Although mobile applications for mental health have been found to be generally acceptable to children and adolescents, there is a lack of convincing evidence of effectiveness on intended mental health outcomes98 and few mobile health apps have been thoroughly tested.97 Self-help interventions including bibliotherapy99 and computerized therapy100 have shown a moderate positive effect size when compared to control groups although they are generally less effective than face to face therapies.101 Importantly, reviews have tended to conclude that effects are better if there is some therapist input97 , 101 and if parents are involved especially for younger children.96 , 97

The rapid review suggests that loneliness that may result from disease containment measures in the COVID-19 context could be associated with subsequent mental health problems in young people. Strategies to prevent the development of such problems should be an international priority.

Footnotes

The authors have reported no funding for this work. All research at Great Ormond Street Hospital NHS Foundation Trust and UCL Great Ormond Street Institute of Child Health is made possible by the NIHR Great Ormond Street Hospital Biomedical Research Centre. This report is independent research. The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR, or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Author Contributions Conceptualization: Loades, Chatburn, Reynolds, Shafran, Borwick, Crawley

Data curation: Loades, Chatburn, Higson-Sweeney, Brigden, Linney, McManus

Formal analysis: Loades, Chatburn, Reynolds

Methodology: Loades, Chatburn, Reynolds

Project administration: Loades, Chatburn, Higson-Sweeney, Borwick

Supervision: Reynolds, Shafran, Crawley

Writing – original draft: Loades

Writing – review and editing: Loades, Chatburn, Higson-Sweeney, Reynolds, Shafran, Brigden, Linney, McManus, Borwick, Crawley

ORCID

Maria Elizabeth Loades, DClinPsy: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0839-3190

Eleanor Chatburn, MA: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6745-6737

Nina Higson-Sweeney, BSc: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6926-0463

Shirley Reynolds, PhD: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9975-2023

Roz Shafran, PhD: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2729-4961

Amberly Brigden, MSc: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7958-7881

Catherine Linney, MA: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3873-3686

Megan Niamh McManus, BSc candidate: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7206-3444

Catherine Borwick, MSc: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5423-7279

Esther Crawley, PhD: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2521-0747

Disclosure: Dr. Loades has received funding from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR Doctoral Research Fellowship, DRF-2016-09-021). Ms. Brigden has received funding from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR Doctoral Research Fellowship, DRF-2017-10-169). Profs. Reynolds, Shafran, Crawley and Mss. Chatburn, Higson-Sweeney, Linney, McManus, and Borwick have reported no biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interest.

Supplemental Material

Table S1.

Database Search: Ovid MEDLINE (R)

| 1 | exp Adolescent/ or exp Child/ or exp Child, Preschool/ or exp Infant/ or exp Minors/ or exp Pediatrics/ | 35,33,050 |

| 2 | (adolesc∗ or preadolesc∗ or pre-adolesc∗ or boy∗ or girl∗ or child∗ or infan∗ or preschool∗ or pre-school∗ or juvenil∗ or minor∗ or pe?diatri∗ or pubescen∗ or pre-pubescen∗ or prepubescen∗ or puberty or teen∗ or young∗ or youth∗ or school∗ or high-school∗ or highschool∗ or schoolchild∗ or school child∗).tw,kf. | 29,51,684 |

| 3 | 1 or 2 | 47,48,091 |

| 4 | quarantine∗.tw,kf. | 4,350 |

| 5 | exp Quarantine/ | 2,093 |

| 6 | Quarantine.tw,kf. | 3,975 |

| 7 | exp social isolation/ | 17,148 |

| 8 | (isolation and (infect∗ or SARS or influenza or flu or MERS or ebola or COVID-19)).tw,kf. | 34,141 |

| 9 | exp Loneliness/ | 3,552 |

| 10 | 4 or 5 or 6 or 7 or 8 or 9 | 56,227 |

| 11 | anxiet∗/ or anxious∗/ or “anxiety disorder∗".tw,kf. | 29,320 |

| 12 | depress∗/ or “internal∗ disord∗"/ or “low mood".tw,kf. | 737 |

| 13 | depressive disorder/ | 72,188 |

| 14 | exp depression/ | 1,15,922 |

| 15 | depress∗.tw,kf. | 4,45,459 |

| 16 | exp adjustment disorders/ | 4,197 |

| 17 | adjustment disorder∗.tw,kf. | 1,642 |

| 18 | low mood.tw,kf. | 737 |

| 19 | obsessive-compulsive disorder.tw,kf. | 12,336 |

| 20 | stress disorders, traumatic/ | 672 |

| 21 | stress disorders, post-traumatic/ | 31,840 |

| 22 | trauma∗.tw,kf. | 3,53,295 |

| 23 | (((post-trauma∗ or posttrauma∗) adj stress) or PTSD).tw,kf. | 35,040 |

| 24 | 11 or 12 or 13 or 14 or 15 or 16 or 17 or 18 or 19 or 20 or 21 or 22 or 23 | 8,53,134 |

| 25 | 3 and 10 and 24 | 1,277 |

Note: Search conducted March 29, 2020. Full references saved as Medline 290320 v1.

Table S2.

Database Search: Ovid PsycINFO

| 1 | (adolescent or child or child, preschool or infant or minor or pediatrics).ti,ab,id. | 4,25,212 |

| 2 | (adolesc∗ or preadolesc∗ or pre-adolesc∗ or boy∗ or girl∗ or child∗ or infan∗ or preschool∗ or pre-school∗ or juvenil∗ or minor∗ or pe?diatri∗ or pubescen∗ or pre-pubescen∗ or prepubescen∗ or puberty or teen∗ or youth∗ or school∗ or high-school∗ or highschool∗ or schoolchild∗ or school child∗).ti,ab,id. | 12,27,549 |

| 3 | 1 or 2 | 12,27,549 |

| 4 | quarantine.ti,ab,id. | 179 |

| 5 | exp ∗Social Isolation/ | 5,944 |

| 6 | (isolation and (infect∗ or SARS or influenza or flu or MERS or ebola or COVID-19)).ti,ab,id. | 437 |

| 7 | Disease containment∗.ti,ab,id. | 5 |

| 8 | Lonel∗.ti,ab,id. | 10,569 |

| 9 | exp ∗loneliness/ | 3,642 |

| 10 | 4 or 5 or 6 or 7 or 8 or 9 | 16,688 |

| 11 | anxiet∗/ or anxious∗/ or “anxiety disorder∗".ti,ab,id. | 33,786 |

| 12 | depress∗/ or “internal∗ disord∗"/ or “low mood".ti,ab,id. | 673 |

| 13 | exp ∗depression/ | 19,678 |

| 14 | depress∗.ti,ab,id. | 3,01,583 |

| 15 | exp adjustment disorders/ | 719 |

| 16 | adjustment disorder∗.ti,ab,id. | 1,851 |

| 17 | obsessive-compulsive disorder.ti,ab,id. | 15,268 |

| 18 | post-traumatic stress disorder.ti,ab,id. | 10,195 |

| 19 | trauma∗.ti,ab,id. | 1,07,899 |

| 20 | (((post-trauma∗ or posttrauma∗) adj stress) or PTSD).ti,ab,id. | 44,403 |

| 21 | 11 or 12 or 13 or 14 or 15 or 16 or 17 or 18 or 19 or 20 | 4,31,601 |

| 22 | 3 and 10 and 21 | 1,303 |

Note: Search conducted March 29, 2020. Full references saved as PsycINFO 290320 v1.

Table S3.

Database Search: Web of Science Core Collection

| # 22 | 3,211 | #21 AND #10 AND #3 |

| # 21 | 1,173,555 | #20 OR #19 OR #18 OR #17 OR #16 OR #15 OR #14 OR #13 OR #12 OR #11 |

| # 20 | 64,185 | TS=(((post-trauma∗ or posttrauma∗) NEAR stress) or PTSD) |

| # 19 | 387,085 | TS=trauma∗ |

| # 18 | 15,994 | TS=post traumatic stress disorder |

| # 17 | 25,733 | TS=obsessive compulsive disorder |

| # 16 | 22,119 | TS=adjustment disorder∗ |

| # 15 | 22,104 | TS=adjustment disorders |

| # 14 | 627,349 | TS=depress∗ |

| # 13 | 494,240 | TS=depression |

| # 12 | 628,267 | TS=(depress∗ OR " internal∗ disord∗ " OR " low mood ") |

| # 11 | 283,559 | TS=(anxiet∗ OR anxious∗ OR " anxiety disorder∗ ") |

| # 10 | 77,296 | #9 OR #8 OR #7 OR #6 OR #5 OR #4 |

| # 9 | 12,570 | TS=loneliness |

| # 8 | 15,420 | TS=Lonel∗ |

| # 7 | 2,586 | TS=Disease containment∗ |

| # 6 | 35,721 | TS=(isolation and (infect∗ or SARS or influenza or flu or MERS or ebola or COVID-19)) |

| # 5 | 17,794 | TS=social isolation |

| # 4 | 8,759 | TS=quarantine |

| # 3 | 3,591,598 | #2 OR #1 |

| # 2 | 3,581,837 | TS=(adolesc∗ or preadolesc∗ or pre-adolesc∗ or boy∗ or girl∗ or child∗ or infan∗ or preschool∗ or pre-school∗ or juvenil∗ or minor∗ or pe?diatri∗ or pubescen∗ or pre-pubescen∗ or prepubescen∗ or puberty or teen∗ or youth∗ or school∗ or high-school∗ or highschool∗ or schoolchild∗ or school child∗) |

| # 1 | 2,450,709 | TS=(adolescent OR child OR child, preschool OR infant OR minor OR pediatrics) |

Note: Search conducted March 29, 2020. Applied ‘English language’ limit = 3,012

References

- 1.Brooks S.K., Webster R.K., Smith L.E. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence. Lancet. 2020;395:912–920. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30460-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hossain M.M., Sultana A., Purohit N. Mental health outcomes of quarantine and isolation for infection prevention: a systematic umbrella review of the global evidence. psyarxiv.com/dz5v2/ Available at: Published 2020. Accessed April 10, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Deighton J., Lereya S.T., Casey P., Patalay P., Humphrey N., Wolpert M. Prevalence of mental health problems in schools: poverty and other risk factors among 28 000 adolescents in England. Br J Psychiatry. 2019;215:565–567. doi: 10.1192/bjp.2019.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Perlman D., Peplau L.A. Toward a social psychology of loneliness. Pers Relat. 1981;3:31–56. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oxford ARC Study. Achieving resilience during COVID-19 weekly report 2. 2020. Available at: http://mentalhealthresearchmatters.org.uk/achieving-resilience-during-covid-19-psycho-social-risk-protective-factors-amidst-a-pandemic-in-adolescents/. Accessed May 22, 2020.

- 6.Young Minds. Coronavirus report March 2020. 2020. Available at: https://youngminds.org.uk/media/3708/coronavirus-report_march2020.pdf. Accessed May 24, 2020.

- 7.Mental Health Foundation. Loneliness during Corona-virus. 2020. Available at: https://www.mentalhealth.org.uk/coronavirus/loneliness-during-coronavirus. Accessed May 22, 2020.

- 8.Wang J., Lloyd-Evans B., Giacco D. Social isolation in mental health: a conceptual and methodological review. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2017;52:1451–1461. doi: 10.1007/s00127-017-1446-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.World Health Organization . World Health Organization; Geneva: 2017. Rapid reviews to strengthen health policy and systems: a practical guide. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Garritty C.G., G, Kamel C. Cochrane Rapid Reviews. Interim guidance from the Cochrane Rapid Review Methods Group. 2020. https://methods.cochrane.org/rapidreviews/sites/methods.cochrane.org.rapidreviews/files/public/uploads/cochrane_rr_-_guidance-23mar2020-v1.pdf Available at:

- 11.Ganann R., Ciliska D., Thomas H. Expediting systematic reviews: methods and implications of rapid reviews. Implement Sci. 2010;5:56. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-5-56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tricco A.C., Antony J., Zarin W. A scoping review of rapid review methods. BMC Med. 2015;13:224. doi: 10.1186/s12916-015-0465-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Manuell M.E., Cukor J. Mother Nature versus human nature: public compliance with evacuation and quarantine. Disasters. 2011;35:417–442. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7717.2010.01219.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.National Institutes of Health. Study Assessment Tools. 2018. Available at: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools. Accessed May 22, 2020.

- 15.Moher D., Liberati A., Tetzlaff J., Altman D.G., PRISMA Group Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Westfall J., Yarkoni T. Statistically controlling for confounding constructs is harder than you think. PLoS One. 2016;11 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0152719. e0152719-e0152719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alpaslan A.H., Kocak U., Avci K. Gender-related factors for depressive symptoms in Turkish adolescents. J Child Adolesc Psychiatr Nurs. 2016;29:23–29. doi: 10.1111/jcap.12131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Arslan G. School belongingness, well-being, and mental health among adolescents: exploring the role of loneliness, Aust J Psychol. 2020:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baskin T.W., Wampold B.E., Quintana S.M., Enright R.D. Belongingness as a protective factor against loneliness and potential depression in a multicultural middle school. Couns Psychol. 2010;38:626–651. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brage D., Meredith W., Woodward J. Correlates of loneliness among midwestern adolescents. Adolescence. 1993;28:685–693. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brage D., Campbell-Grossman C., Dunkel J. Psychological correlates of adolescent depression. J Child Adolesc Psychiatr Nurs. 1995;8:23–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6171.1995.tb00547.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chang E.C., Wan L., Li P. Loneliness and suicidal risk in young adults: does believing in a changeable future help minimize suicidal risk among the lonely? J Psychol. 2017;151:453–463. doi: 10.1080/00223980.2017.1314928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Doman L.C.H., Le Roux A. The relationship between loneliness and psychological well-being among third-year students: a cross-cultural investigation. Int J Culture Ment Health. 2012;5:153–168. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Erdur-Baker O., Bugay A. Mediator and moderator role of loneliness in the relationship between peer victimization and depressive symptoms. Aust J Guidance Counsel. 2011;21:175–185. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ginter E.J., Lufi D., Dwinell P.L. Loneliness, perceived social support, and anxiety among Israeli adolescents. Psychol Rep. 1996;79(1):335–341. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1996.79.1.335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Heredia D. Jr, Sanchez Gonzalez M.L., Rosner C.M. The influence of loneliness and interpersonal relations on Latina/o Middle School Students’ Wellbeing. J Latinos Educ. 2017;16:338–348. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Houghton S.H., Carroll J.A., Wood L., Baffour B. It hurts to be lonely! Loneliness and positive mental wellbeing in Australian rural and urban adolescents. Journal Psychol Counsel Sch. 2016;26:52–67. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hudson D.B., Elek S.M., Campbell-Grossman C. Depression, self-esteem, loneliness, and social support among adolescent mothers participating in the new parents project. Adolescence. 2000;35:445–453. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hutcherson S.T., Epkins C.C. Differentiating parent- and peer-related interpersonal correlates of depressive symptoms and social anxiety in preadolescent girls. J Soc Pers Relat. 2009;26:875–897. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jackson J., Cochran S.D. Loneliness and psychological distress. J Psychol. 1991;125:257–262. doi: 10.1080/00223980.1991.10543289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Johnson H.D., Lavoie J.C., Mahoney M. Interparental conflict and family cohesion: predictors of loneliness, social anxiety, and social avoidance in late adolescence. 2001. Available at: Accessed September 29, 2020. [DOI]

- 32.Kim O. Sex differences in social support, loneliness, and depression among Korean college students. Psychol Rep. 2001;88:521–526. doi: 10.2466/pr0.2001.88.2.521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Koenig L.J., Isaacs A.M., Schwartz J.A. Sex differences in adolescent depression and loneliness: why are boys lonelier if girls are more depressed? J Res Personal. 1994;28:27–43. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lasgaard M.G., L, Bramsen R.H., Trillingsgaarf T., Elklit A. Different sources of loneliness are associated with different forms of psychopathology in adolescence. J Res Personal. 2011;45:233–237. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lau S., Chan D.W., Lau P.S. Facets of loneliness and depression among Chinese children and adolescents. J Soc Psychol. 1999;139:713–729. doi: 10.1080/00224549909598251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Majd Ara E., Talepasand S., Rezaei A.M. A structural model of depression based on interpersonal relationships: the mediating role of coping strategies and loneliness. Noro Psikiyatr Ars. 2017;54:125–130. doi: 10.5152/npa.2017.12711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mahon N.E., Yarcheski A., Yarcheski T.J. Mental health variables and positive health practices in early adolescents. Psychol Rep. 2001;88:1023–1030. doi: 10.2466/pr0.2001.88.3c.1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Markovic A., Bowker J.C. Social surrogacy and adjustment: exploring the correlates of having a "social helper" for shy and non-shy young adolescents. J Genet Psychol. 2015;176:110–129. doi: 10.1080/00221325.2015.1007916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Matthews T., Danese A., Wertz J. Social isolation, loneliness and depression in young adulthood: a behavioural genetic analysis. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2016;51:339–348. doi: 10.1007/s00127-016-1178-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mclntyre J.C.W., J, Corcoran R., Harrison Woods P., Bentall R.P. Academic and non-academic predictors of student psychological distress: the role of social identity and loneliness. J Ment Health. 2018;27:230–239. doi: 10.1080/09638237.2018.1437608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Moore D., Schultz N.R., Jr. Loneliness at adolescence: correlates, attributions, and coping. J Youth Adolesc. 1983;12:95–100. doi: 10.1007/BF02088307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mounts N.S., Valentiner D.P., Anderson K.L., Boswell M.K. Shyness, sociability, and parental support for the college transition: relation to adolescents’ adjustment. J Youth Adolesc. 2006;35:68–77. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Neto F., Barros J. Psychosocial concomitants of loneliness among students of Cape Verde and Portugal. J Psychol. 2000;134:503–514. doi: 10.1080/00223980009598232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Purwono U., French D.C. Depression and its relation to loneliness and religiosity in Indonesian Muslim adolescents. Mental Health Religion Culture. 2016;19:218–228. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Richardson C., Oar E., Fardouly J. The moderating role of sleep in the relationship between social isolation and internalising problems in early adolescence. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 2019;50:1011–1020. doi: 10.1007/s10578-019-00901-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Roberts R.E., Chen Y.W. Depressive symptoms and suicidal ideation among Mexican-origin and Anglo adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1995;34:81–90. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199501000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Singhvi M.K., Sehgal S.R., Kumari N. Psychological correlates of loneliness among adolescents. Indian J Psychol Sci. 2011;2:8. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Spithoven A.W., Lodder G.M., Goossens L. Adolescents' loneliness and depression associated with friendship experiences and well-being: a person-centered approach. J Youth Adolesc. 2017;46:429–441. doi: 10.1007/s10964-016-0478-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stednitz J.N., Epkins C.C. Girls' and mothers' social anxiety, social skills, and loneliness: associations after accounting for depressive symptoms. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2006;35:148–154. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3501_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stacciarini J.M., Smith R., Garvan C.W., Wiens B., Cottler L.B. Rural Latinos' mental wellbeing: a mixed-methods pilot study of family, environment and social isolation factors. Community Ment Health J. 2015;51:404–413. doi: 10.1007/s10597-014-9774-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stickley A., Koyanagi A., Koposov R. Loneliness and its association with psychological and somatic health problems among Czech, Russian and U.S. adolescents. BMC Psychiatry. 2016;16:128. doi: 10.1186/s12888-016-0829-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Swami V., Chamorro-Premuzic T., Sinniah D. General health mediates the relationship between loneliness, life satisfaction and depression. A study with Malaysian medical students. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2007;42:161–166. doi: 10.1007/s00127-006-0140-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Thomas K.K., Bowker J.C. Rejection sensitivity and adjustment during adolescence: do friendship self-silencing and parent support matter? J Child Family Stud. 2013;24:608–616. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tu Y., Zhang S. Loneliness and subjective well-being among Chinese undergraduates: the mediating role of self-efficacy. Soc Indic Res. 2014;124:963–980. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Uba I., Yaacob S.N., Juhari R., Talib M.A. Does self-esteem mediate the relationship between loneliness and depression among Malaysian teenagers? Pertanika J Soc Sci Humanit. 2012;20:179–188. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Vanhalst J., Luyckx K., Raes F., Goossens L. Loneliness and depressive symptoms: the mediating and moderating role of uncontrollable ruminative thoughts. J Psychol. 2012;146:259–276. doi: 10.1080/00223980.2011.555433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wang L., Yao J. Life satisfaction and social anxiety among left-behind children in rural China: the mediating role of loneliness. J Community Psychol. 2020;48:258–266. doi: 10.1002/jcop.22252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Xu J., Chen P. The rural children's loneliness and depression in Henan, China: the mediation effect of self-concept. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2019;54:1101–1109. doi: 10.1007/s00127-018-1636-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yadegarfard M., Meinhold-Bergmann M.E., Ho R. Family rejection, social isolation, and loneliness as predictors of negative health outcomes (depression, suicidal ideation, and sexual risk behaviour) among Thai male-to-female transgender adolescents. J LGBT Youth. 2014;11:347–363. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sprang G., Silman M. Posttraumatic stress disorder in parents and youth after health-related disasters. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2013;7:105–110. doi: 10.1017/dmp.2013.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Boivin M.H., S, Bukowski W.M. The roles of social withdrawal, peer rejection, and victimization by peers in predicting loneliness and depressed mood in childhood. Dev Psychopathol. 1995;7:765–785. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Christ S.L., Kwak Y.Y., Lu T. The joint impact of parental psychological neglect and peer isolation on adolescents' depression. Child Abuse Negl. 2017;69:151–162. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2017.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Danneel S., Nelemans S., Spithoven A. Internalizing problems in adolescence: linking loneliness, social anxiety symptoms, and depressive symptoms over time. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2019;47:1691–1705. doi: 10.1007/s10802-019-00539-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Fontaine R.G., Yang C., Burks V.S. Loneliness as a partial mediator of the relation between low social preference in childhood and anxious/depressed symptoms in adolescence. Dev Psychopathol. 2009;21:479–491. doi: 10.1017/S0954579409000261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Jones A.C., Schinka K.C., van Dulmen M.H., Bossarte R.M., Swahn M.H. Changes in loneliness during middle childhood predict risk for adolescent suicidality indirectly through mental health problems. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2011;40:818–824. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2011.614585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ladd G.W., Ettekal I. Peer-related loneliness across early to late adolescence: normative trends, intra-individual trajectories, and links with depressive symptoms. J Adolesc. 2013;36:1269–1282. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2013.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lalayants M., Prince J.D. Loneliness and depression or depression-related factors among child welfare-involved adolescent females. Child Adolesc Soc Work J. 2015;32:167–176. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lapierre M.A., Zhao P., Custer B.E. Short-term longitudinal relationships between smartphone use/dependency and psychological well-being among late adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 2019;65:607–612. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2019.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lasgaard M., Goossens L., Elklit A. Loneliness, depressive symptomatology, and suicide ideation in adolescence: cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2011;39:137–150. doi: 10.1007/s10802-010-9442-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Liu H., Zhang M., Yang Q., Yu B. Gender differences in the influence of social isolation and loneliness on depressive symptoms in college students: a longitudinal study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2020;55:251–257. doi: 10.1007/s00127-019-01726-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Mak H.W., Fosco G.M., Feinberg M.E. The role of family for youth friendships: examining a social anxiety mechanism. J Youth Adolesc. 2018;47:306–320. doi: 10.1007/s10964-017-0738-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Matthews T., Danese A., Wertz J. Social isolation and mental health at primary and secondary school entry: a longitudinal cohort study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2015;54:225–232. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2014.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Qualter P., Brown S.L., Munn P., Rotenberg K.J. Childhood loneliness as a predictor of adolescent depressive symptoms: an 8-year longitudinal study. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010;19:493–501. doi: 10.1007/s00787-009-0059-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Schinka K.C., van Dulmen M.H., Mata A.D., Bossarte R., Swahn M. Psychosocial predictors and outcomes of loneliness trajectories from childhood to early adolescence. J Adolesc. 2013;36:1251–1260. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2013.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Vanhalst J., Goossens L., Luyckx K., Scholte R.H., Engels R.C. The development of loneliness from mid- to late adolescence: trajectory classes, personality traits, and psychosocial functioning. J Adolesc. 2013;36:1305–1312. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2012.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]