Abstract

Summary

We developed 2DImpute, an imputation method for correcting false zeros (known as dropouts) in single-cell RNA-sequencing (scRNA-seq) data. It features preventing excessive correction by predicting the false zeros and imputing their values by making use of the interrelationships between both genes and cells in the expression matrix. We showed that 2DImpute outperforms several leading imputation methods by applying it on datasets from various scRNA-seq protocols.

Availability and implementation

The R package of 2DImpute is freely available at GitHub (https://github.com/zky0708/2DImpute).

Contact

d.anastassiou@columbia.edu

Supplementary information

Supplementary data are available at Bioinformatics online.

1 Introduction

The explosive growth of single-cell RNA-sequencing (scRNA-seq) data in recent years has led to important biological discoveries (Rozenblatt-Rosen et al., 2017; Tirosh and Suvà, 2019; Zhong et al., 2018). Nevertheless, due to the low starting amounts of transcripts, a problem manifested in scRNA-seq data is the ‘dropout effect’ which results in many false zero values in the data (Neu et al., 2017) posing challenges for downstream analyses (Kiselev et al., 2019). To alleviate this problem, in addition to efforts to resolve technical issues, e.g. improving the transcript capture efficiency, imputation algorithms specific to scRNA-seq data have been developed for predicting those missing values due to dropouts. Some methods have been proposed integrating imputation with other processing tasks, such as normalization, batch effect correction and clustering (Prabhakaran et al., 2016; Tang et al., 2019). It is important, however, that imputation is also treated in isolation as simple dropout correction, so that users can have the option of building analysis pipelines processing dropout-corrected data specifically designed for their own particular tasks. The following five imputation methods: MAGIC (van Dijk et al., 2018); SAVER (Huang et al., 2018); scImpute (Li and Li, 2018); DrImpute (Gong et al., 2018); and VIPER (Chen and Zhou, 2018) are among the most widely used, and they rely on predicting values based on information from either similar cells or similar genes, using various approaches. All of these methods are constrained by several restrictions (Supplementary Material).

2 Materials and methods

Here we propose a novel scRNA-seq imputation approach, called 2DImpute (see detailed description in Supplementary Material). In brief, 2DImpute distinguishes dropout-suspected events from true biological zeros by using Jaccard distance-based cell-to-cell relationships and then imputes those predicted dropouts by leveraging the interrelationships across both genes and cells as follows. It first identifies co-expression signatures using the unsupervised ‘attractor metagene’ algorithm (Cheng et al., 2013) and imputes spurious zeros for the genes that are involved in such signatures. It then performs imputation on the remaining dropout values based on cell-to-cell relationships through k nearest neighbor regression across cells, making use of the previously imputed values of the co-expressed genes.

Because scRNA-seq datasets profiled from different protocols have distinct characteristics (Svensson et al., 2017), analyzing the performance of imputation on data profiled by various protocols could provide a more comprehensive assessment for each method. Therefore, to evaluate methods, we selected recently published, high quality, real scRNA-seq datasets (Azizi et al., 2018; Jerby-Arnon et al., 2018; Zheng et al., 2017) profiled on three prevalent scRNA-seq protocols (Smart-seq2, inDrop and 10× Genomics Chromium). Each dataset contains ∼3000 cells and all data were pre-processed accordingly before imputation (Supplementary Material). To evaluate and compare different imputation techniques, we used three types of figure of merit based on several known facts serving as ground truth (Supplementary Material).

3 Results

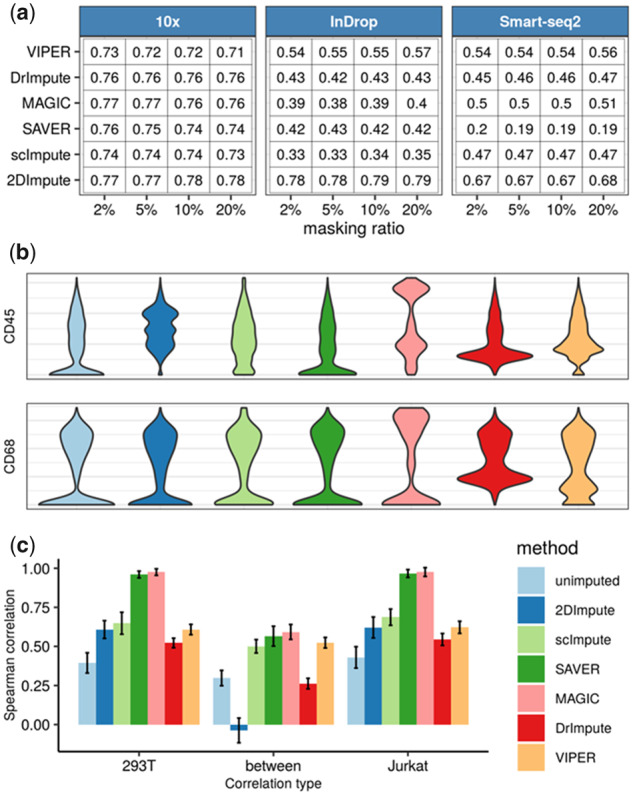

We measured the accuracy of recovering artificially masked non-zeros (Li and Li, 2018; Pierson and Yau, 2015) by different imputation methods in each scRNA-seq dataset. Using different evaluation metrics, 2DImpute stayed as the top performer, whereas other methods showed worse and unstable performance when applied to different datasets (Fig. 1a and Supplementary Fig. S1).

Fig. 1.

Evaluation of 2DImpute in comparison with other imputation methods. (a) Imputation accuracy measured by Pearson correlation between imputed and actual values for non-zero values, which were artificially masked to zero. The masking ratio (2%, 5%, 10% and 20%) is defined as the percentage of a set of non-zero entries in the data matrix (Supplementary Material). (b) Violin plots showing the distributions of universally expressed gene CD45 and the macrophage-specific gene CD68 before (annotated as ‘unimputed’) and after imputation. (c) Bar plots corresponding to the mean pairwise cell-to-cell Spearman correlation in data without and with imputation, in which error bars corresponds to 1 SD; ‘293T’ and ‘Jurkat’ represent the ‘intra-cell’ correlations for the two cell types, respectively; ‘between’ represents the ‘inter-cell’ correlations

We also evaluated the accuracy of distinguishing true from false zeros, using two methods. First, we compared imputation methods in the particular case of fluorescence-activated cell sorting purified cells (Azizi et al., 2018), in which case we have the ground truth that all zeros in the fluorescent labeling gene (which is CD45 in this case) are false and in need of imputation. As shown in Figure 1b, 2DImpute is the only method that combines (i) the correct prediction that all zeros in CD45 are dropouts and has them imputed, while also (ii) retaining a separation between predicted true and false zeros for other genes (e.g. macrophage marker CD68). In addition, we validated the results in cases of other genes and datasets (Supplementary Figs S2 and S3). Second, we used Splatter-simulated (Zappia et al., 2017) datasets to provide ground truth for true-versus-false zeros (Supplementary Material). The results showed that 2DImpute is the only method that had balanced performance (Supplementary Table S1), by simultaneously exhibiting high sensitivity and high specificity (>0.5 for both).

Furthermore, we assessed imputation methods by examining their ability to recover cell-to-cell relationships by only strengthening ‘intra-cell’ correlations using a dataset consisting of a 50%:50% mixture of Jurkat cells and 293T cells (Zheng et al., 2017). 2DImpute was the only method that not only successfully reinforced the intra-cell correlation but also kept the inter-cell correlation to a low level (Fig. 1c). We obtained consistent results by using Pearson correlation (Supplementary Fig. S4). We also assessed the effects of imputation on gene-to-gene correlations by designing experiments based on permuted real data (Supplementary Table S2).

Imputation techniques are not required to be implemented in real-time; therefore, low computational complexity is not a fundamental requirement as long as it is reasonable. We compared the computational efficiencies of various methods, concluding that 2DImpute has reasonable complexity (Supplementary Table S3). We found that MAGIC was the fastest method, whereas VIPER had particularly slow performance in some cases.

4 Discussion

In conclusion, each of the prevalent methods has several drawbacks, while 2DImpute tends to balance the benefit of effective imputation and the risk of over imputation. It distinguishes dropouts from true zeros and leverages interrelationships both among genes and among cells. The algorithm does not require prior knowledge of the number of cell sub-populations; it does not make arbitrary assumptions of statistical models for expression distributions and is robust for use in various prevalent scRNA-seq platforms. Improvements in scRNA-seq imputation techniques will benefit subsequent analyses in many aspects, including network analysis, which is currently limited by false zero values.

Financial Support: none declared.

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

Supplementary Material

References

- Azizi E. et al. (2018) Single-cell map of diverse immune phenotypes in the breast tumor microenvironment. Cell, 174, 1293–1308.e36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen M., Zhou X. (2018) VIPER: variability-preserving imputation for accurate gene expression recovery in single-cell RNA sequencing studies. Genome Biol., 19, 196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng W.-Y. et al. (2013) Biomolecular events in cancer revealed by attractor metagenes. PLoS Comput. Biol., 9, e1002920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong W. et al. (2018) DrImpute: imputing dropout events in single cell RNA sequencing data. BMC Bioinformatics, 19, 220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang M. et al. (2018) SAVER: gene expression recovery for single-cell RNA sequencing. Nat. Methods, 15, 539–542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jerby-Arnon,L. et al (2018) A cancer cell program promotes T cell exclusion and resistance to checkpoint blockade. Cell, 175, 984–997.e24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiselev V.Y. et al. (2019) Challenges in unsupervised clustering of single-cell RNA-seq data. Nat. Rev. Genet., 20, 273–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W.V., Li J.J. (2018) An accurate and robust imputation method scImpute for single-cell RNA-seq data. Nat. Commun., 9, 997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neu K.E. et al. (2017) Single-cell genomics: approaches and utility in immunology. Trends Immunol., 38, 140–149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierson E. et al. (2015) ZIFA: dimensionality reduction for zero-inflated single-cell gene expression analysis. Genome Biol., 16, 241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prabhakaran S. et al. (2016) Dirichlet process mixture model for correcting technical variation in single-cell gene expression data. JMLR Workshop Conf. Proc., 48, 1070–1079. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rozenblatt-Rosen O. et al. (2017) The Human Cell Atlas: from vision to reality. Nature, 550, 451–453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svensson V. et al. (2017) Power analysis of single-cell RNA-sequencing experiments. Nat. Methods, 14, 381–387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang W. et al. (2019) bayNorm: Bayesian gene expression recovery, imputation and normalisation for single cell RNA-sequencing data. Bioinformatics, [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tirosh I., Suvà M.L. (2019) Deciphering human tumor biology by single-cell expression profiling. Annu. Rev. Cancer Biol., 3, 151–166. [Google Scholar]

- van Dijk D. et al. (2018) Recovering gene interactions from single-cell data using data diffusion. Cell, 174, 716–729.e27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zappia L. et al. (2017) Splatter: simulation of single-cell RNA sequencing data. Genome Biol., 18, 174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng G.X.Y. et al. (2017) Massively parallel digital transcriptional profiling of single cells. Nat. Commun., 8, 14049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong S. et al. (2018) A single-cell RNA-seq survey of the developmental landscape of the human prefrontal cortex. Nature, 555, 524–528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.