Key Points

Question

Is there an association between shorter door-to-needle time with thrombolytic therapy and long-term mortality and hospital readmission in patients with acute ischemic stroke?

Findings

In this US retrospective cohort study that included 61 426 patients with acute ischemic stroke treated with intravenous tissue plasminogen activator, longer door-to-needle times (within 90 minutes after hospital arrival) were significantly associated with higher all-cause mortality at 1 year (hazard ratio per 15-minute increase in time, 1.04) and higher likelihood of all-cause readmission at 1 year (hazard ratio per 15-minute increase in time, 1.02).

Meaning

These findings support efforts to shorten time to thrombolytic therapy.

Abstract

Importance

Earlier administration of intravenous tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) in acute ischemic stroke is associated with reduced mortality by the time of hospital discharge and better functional outcomes at 3 months. However, it remains unclear whether shorter door-to-needle times translate into better long-term outcomes.

Objective

To examine whether shorter door-to-needle times with intravenous tPA for acute ischemic stroke are associated with improved long-term outcomes.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This retrospective cohort study included Medicare beneficiaries aged 65 years or older who were treated for acute ischemic stroke with intravenous tPA within 4.5 hours from the time they were last known to be well at Get With The Guidelines–Stroke participating hospitals between January 1, 2006, and December 31, 2016, with 1-year follow-up through December 31, 2017.

Exposures

Door-to-needle times for intravenous tPA.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary outcomes were 1-year all-cause mortality, all-cause readmission, and the composite of all-cause mortality or readmission.

Results

Among the 61 426 patients treated with tPA within 4.5 hours, the median age was 80 years and 43.5% were male. The median door-to-needle time was 65 minutes (interquartile range, 49-88 minutes). The 48 666 patients (79.2%) who were treated with tPA and had door-to-needle times of longer than 45 minutes, compared with those treated within 45 minutes, had significantly higher all-cause mortality (35.0% vs 30.8%, respectively; adjusted HR, 1.13 [95% CI, 1.09-1.18]), higher all-cause readmission (40.8% vs 38.4%; adjusted HR, 1.08 [95% CI, 1.05-1.12]), and higher all-cause mortality or readmission (56.0% vs 52.1%; adjusted HR, 1.09 [95% CI, 1.06-1.12]). The 34 367 patients (55.9%) who were treated with tPA and had door-to-needle times of longer than 60 minutes, compared with those treated within 60 minutes, had significantly higher all-cause mortality (35.8% vs 32.1%, respectively; adjusted hazard ratio [HR], 1.11 [95% CI, 1.07-1.14]), higher all-cause readmission (41.3% vs 39.1%; adjusted HR, 1.07 [95% CI, 1.04-1.10]), and higher all-cause mortality or readmission (56.8% vs 53.1%; adjusted HR, 1.08 [95% CI, 1.05-1.10]). Every 15-minute increase in door-to-needle times was significantly associated with higher all-cause mortality (adjusted HR, 1.04 [95% CI, 1.02-1.05]) within 90 minutes after hospital arrival, but not after 90 minutes (adjusted HR, 1.01 [95% CI, 0.99-1.03]), higher all-cause readmission (adjusted HR, 1.02; 95% CI, 1.01-1.03), and higher all-cause mortality or readmission (adjusted HR, 1.02 [95% CI, 1.01-1.03]).

Conclusions and Relevance

Among patients aged 65 years or older with acute ischemic stroke who were treated with tissue plasminogen activator, shorter door-to-needle times were associated with lower all-cause mortality and lower all-cause readmission at 1 year. These findings support efforts to shorten time to thrombolytic therapy.

This cohort study estimates associations between intravenous tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) door-to-needle times of less than 4.5 hours for acute ischemic stroke and 1-year mortality or readmission among Medicare beneficiaries aged 65 years or older.

Introduction

Intravenous tissue plasminogen activator (tPA), compared with no reperfusion therapy, has been demonstrated in randomized trials to improve 3-month functional outcomes after acute ischemic stroke,1,2 and 1-year to 1.5-year functional outcomes.3,4 Moreover, earlier administration of tPA, compared with later administration, has been shown to be associated with lower risk of in-hospital mortality and hemorrhagic transformation, and better functional outcomes at discharge and at 90 days.1,5,6 However, the relationship between earlier thrombolytic treatment and long-term outcomes has not been well delineated.

For national quality improvement programs of patient care, the relationship between the time interval from hospital arrival (“door”) to the start of the pharmacological infusion (“needle”) and long-term outcomes is of special relevance because door-to-needle time is directly under the control of hospital stroke teams and systems of care. The national quality initiative, Target: Stroke, was launched in January 2010 by the American Heart Association and the American Stroke Association to assist hospitals in reducing door-to-needle times. A series of key best practice strategies were disseminated to hospitals with the goal to achieve door-to-needle times within 60 minutes for at least 50% of patients treated with tPA, which was later raised to 75% of patients, and then the additional goal of door-to-needle times within 45 minutes for at least 50% of patients.7,8

Faster door-to-needle times have been associated with better in-hospital outcomes9; however, their relationship to long-term outcomes at 1 year have not been clearly demonstrated. This study aimed to test the hypothesis that shorter door-to-needle times for tPA are associated with lower 1-year all-cause mortality, all-cause readmission, and the composite of all-cause mortality or readmission among patients hospitalized with acute ischemic stroke.

Methods

Data Source and Study Population

This US cohort included Medicare beneficiaries aged 65 years or older who were treated with intravenous tPA for acute ischemic stroke at Get With The Guidelines (GWTG)–Stroke participating hospitals between January 1, 2006, and December 31, 2016, with 1-year follow-up through December 31, 2017. Patient clinical data were obtained from the GWTG-Stroke database. The GWTG-Stroke program was launched by the American Heart Association and the American Stroke Association to support continuous quality improvement within hospital systems of care for patients with stroke and transient ischemic attack.

Trained hospital personnel were instructed to collect the data (which included demographics, medical history, stroke onset time, hospital arrival time, in-hospital diagnostic studies, tPA treatment initiation time, and in-hospital outcomes) of consecutive patients treated for acute ischemic stroke or transient ischemic attack by using either prospective clinical identification, retrospective identification via International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, and International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision, codes, or a combination of data identification methods.10,11

In an effort to monitor racial/ethnic disparities in stroke care, data on race/ethnicity were recorded by hospital staff from various sources, including patient self-designation, administrative personnel during the registration process, or nursing intake forms.12,13,14 The data entry tool used supports a multiselect option that includes single racial, multiple racial, and ethnic categories, and a separate data element for Hispanic ethnicity (yes vs no or not documented).12

Data on hospital-level characteristics (eg, the number of beds, academic status, and geographic region) were obtained from the American Hospital Association database. A prior audit showed the overall accuracy of GWTG-Stroke was above 90% for most variables and that time-related performance measures had excellent reliability (κ ≥ 0.75) and door-to-needle times within 60 minutes had good reliability (κ = 0.72).11

Each participating hospital received either human research approval to enroll cases without individual patient consent under the common rule,15 or a waiver of authorization and exemption from subsequent review by its institutional review board. The Duke Clinical Research Institute served as the data analysis center.

To obtain longitudinal outcomes, the GWTG-Stroke records were linked to Medicare claims files by matching on a series of indirect identifiers, which included hospital admission and discharge dates, identification of the hospital, and the patient’s date of birth and sex as previously reported and validated.16 Medicare is a national health insurance program in the US that covers 98% of adults aged 65 years or older.17 Prior work has demonstrated that patients in the linked database of GWTG-Stroke and Medicare are representative of Medicare patients with ischemic stroke in the US.18

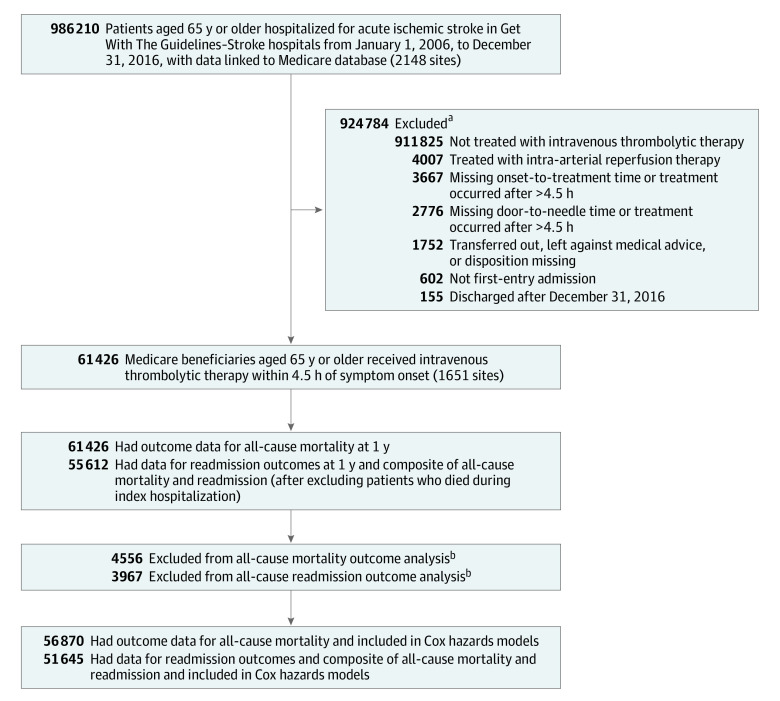

Study entry criteria required patients to (1) have been aged 65 years or older; (2) have a discharge diagnosis of acute ischemic stroke; (3) have been treated with intravenous tPA within 4.5 hours of the time they were last known to be well; (4) have had a documented door-to-needle time; (5) not have been treated with a concomitant therapy with intra-arterial reperfusion techniques; (6) have had the admission be the first for stroke during the study period; and (7) not have been transferred to another acute care hospital, left against medical advice, or without a documented site of discharge disposition (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Flow of Medicare Patients in the Get With The Guidelines–Stroke Study.

aExclusions are ordered by frequency rather than actual sequence applied.

bExcluded from Cox proportional hazards models because of missing data on hospital characteristics and National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale score.

Outcomes

The prespecified primary outcomes included 1-year all-cause mortality, 1-year all-cause readmission, and the composite of all-cause mortality or readmission at 1 year. One-year cardiovascular readmission was a prespecified secondary outcome and was defined as a readmission with a primary discharge diagnosis of hypertension, coronary artery disease, myocardial infarction, heart failure, abdominal or aortic aneurysm, valvular disease, and cardiac arrhythmia.

Recurrent stroke readmission, a post hoc secondary outcome, was defined as a readmission for transient ischemic attack, ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke, carotid endarterectomy or stenting, but not for direct complications of index stroke. The time to death was measured starting from the index admission date. The time to readmission outcomes was measured starting from the index discharge date.

Statistical Analyses

The Pearson χ2 test was used for categorical variables and the Wilcoxon rank-sum test (Kruskal-Wallis test for >2 categories) for continuous variables to compare patient and hospital characteristics. Standardized differences (calculated as the difference in means or proportions divided by a pooled estimate of the SD × 100 to get a percentage) were used for comparisons between 2 groups.

An absolute standardized difference greater than 10% indicates significant imbalance of a covariate, whereas a standardized difference of 10% or less supports the assumption of balance between treatment groups.19 Door-to-needle time was first analyzed using the prespecified times of within 45 minutes or within 60 minutes vs longer than those targets.7,8 We also evaluated time as continuous variable, as a categorical variable in 15-minute increments using within 30 minutes as the reference group, and in 45-minute and 60-minute increments.

The primary analysis included all patients during the full study period. Patients treated during the 2015-2016 time frame, when endovascular thrombectomy use was increasing, were analyzed in the sensitivity analyses.20

Door-to-needle time associations with outcomes were evaluated for nonlinearity which, if present, was addressed with linear splines. Cox proportional hazards models were used to examine the associations of door-to-needle timeliness and each 1-year outcome with robust variance estimation to account for the clustering of patients within hospitals. The variables used in the risk models were patient-level and hospital-level risk characteristics, which have been shown to be predictive of mortality and have been used in prior GWTG-Stroke analyses.21,22,23,24,25,26

The patient-level variables included age, sex, race/ethnicity, vascular risk factors (atrial fibrillation or flutter, previous stroke or transient ischemic attack, history of coronary artery disease or myocardial infarction, heart failure, carotid stenosis, diabetes, peripheral artery disease, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and smoking), arrival information (arriving by emergency medical services and during on vs off hours), and stroke severity as measured by the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale. On hours were defined as 7:00 am to 6:00 pm on any weekday. Off hours were defined as any other time, including evenings, nights, weekends, and national holidays. Prior studies using this prespecified time cutoff have shown that presenting during off hours was associated with inferior quality of care, inferior intravenous thrombolytic treatment, and in-hospital mortality.22,23

The American Heart Association/American Stroke Association Target: Stroke initiative was accounted for by adjusting for admission time before or after 2010. Hospital characteristics included geographic region, urban or rural hospital location, total number of beds, annual volume of ischemic stroke cases, academic status, and whether or not the site was a certified stroke center. The proportional hazards assumption was assessed using the Schoenfeld residual test and it was met because the P value was > .05 for the correlation between weighted residuals and failure times for door-to-needle times. The absolute risk estimates between door-to-needle time categories were calculated using the direct adjustment method and the whole population was used to compute event estimates as an average of estimates for all data observations.

Continuous variables were evaluated for nonlinearity in relation to the outcomes, which, if present, were addressed with linear splines. Multiple imputation with 10 imputations was used to impute missing data for covariates with the fully conditional specification method to account for possible confounders. If the medical history of a patient was missing, it was assumed that no medical conditions were present. Hospital characteristics and the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale score were not imputed. The cause-specific hazards model was used to account for the competing risk of mortality for readmissions.27

Cumulative incidence curves were generated to estimate the incidence of each outcome of interest. Differences in mortality and the composite of all-cause mortality or readmission at 1 year were compared using the log-rank test. Differences in all-cause readmission, cardiovascular readmission, and recurrent stroke readmission were compared using the Gray test. In addition, the cumulative incidence rates by door-to-needle time were provided.

All statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc). All hypothesis tests were 2-sided and P values < .05 were considered statistically significant. The findings should be interpreted as exploratory given the absence of correction for multiple comparisons.

Results

Patient-level and hospital-level characteristics of the included population by door-to-needle times in 15-minute increments appear in Table 1 and by the door-to-needle times of 45 minutes and 60 minutes in eTable 1 in the Supplement. Among the 61 426 Medicare beneficiaries treated with intravenous tPA within 4.5 hours of the time they were last known to be well at the 1651 GWTG-Stroke participating hospitals, the median age was 80 years, 43.5% were male, 82.0% were non-Hispanic white, 8.7% were non-Hispanic black, 4.0% were Hispanic, and 5.3% were of other race/ethnicity. More patients that arrived during off hours were treated within longer door-to-needle times (40.7% for ≤30 minutes, 45.6% for 31-45 minutes, 50.6% for 46-60 minutes, 53.5% for 61-75 minutes, and 56.3% for >75 minutes; P < .001). Despite having longer onset-to-arrival times, some patients had shorter onset-to-needle and door-to-needle times.

Table 1. Patient and Hospital Characteristics by Door-to-Needle Times in 15-Minute Increments.

| Overalla | Door-to-needle time, mina | P valueb | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤30 | 31-45 | 46-60 | 61-75 | >75 | |||

| Patient characteristics | |||||||

| No. of patients | 61 426 | 3419 (5.6) | 9341 (15.2) | 14 299 (23.2) | 11 357 (18.5) | 23 010 (37.5) | |

| Age, median (IQR), y | 80 (73-86) | 79 (72-86) | 80 (73-86) | 80 (73-86) | 80 (73-86) | 80 (73-86) | <.001 |

| Age group, y | |||||||

| 65-74 | 18 658 (30.4) | 1152 (33.7) | 2943 (31.5) | 4396 (30.7) | 3369 (29.7) | 6798 (29.5) | <.001 |

| 75-84 | 23 331 (38.0) | 1227 (35.9) | 3516 (37.6) | 5311 (37.1) | 4360 (38.4) | 8917 (38.8) | |

| ≥85 | 19 437 (31.6) | 1040 (30.4) | 2882 (30.9) | 4592 (32.1) | 3628 (31.9) | 7295 (31.7) | |

| Sex | |||||||

| Male | 26 715 (43.5) | 1613 (47.2) | 4274 (45.8) | 6372 (44.6) | 4867 (42.9) | 9589 (41.7) | <.001 |

| Female | 34 711 (56.5) | 1806 (52.8) | 5067 (54.2) | 7927 (55.4) | 6490 (57.1) | 13 421 (58.3) | |

| Race/ethnicity | (n = 61 340) | (n = 3413) | (n = 9335) | (n = 14 282) | (n = 11 338) | (n = 22 972) | |

| Non-Hispanic white | 50 324 (82.0) | 2809 (82.3) | 7651 (82.0) | 11 659 (81.6) | 9359 (82.5) | 18 846 (82.0) | .01 |

| Non-Hispanic black | 5329 (8.7) | 289 (8.5) | 787 (8.4) | 1239 (8.7) | 950 (8.4) | 2064 (9.0) | |

| Hispanic | 2452 (4.0) | 121 (3.5) | 351 (3.8) | 603 (4.2) | 435 (3.8) | 942 (4.1) | |

| Otherc | 3235 (5.3) | 194 (5.7) | 546 (5.8) | 781 (5.5) | 594 (5.2) | 1120 (4.9) | |

| Hospital arrival mode | (n = 58 652) | (n = 3350) | (n = 9020) | (n = 13 690) | (n = 10 831) | (n = 21 761) | |

| Emergency medical service | 49 797 (84.9) | 2851 (85.1) | 7819 (86.7) | 11 690 (85.4) | 9130 (84.3) | 18 307 (84.1) | <.001 |

| Private transport | 7617 (13.0) | 278 (8.3) | 948 (10.5) | 1734 (12.7) | 1524 (14.1) | 3133 (14.4) | |

| Transfer from another hospital | 889 (1.5) | 199 (5.9) | 214 (2.4) | 193 (1.4) | 111 (1.0) | 172 (0.8) | |

| Unknown | 349 (0.6) | 22 (0.7) | 39 (0.4) | 73 (0.5) | 66 (0.6) | 149 (0.7) | |

| Hospital arrival during off hoursd | 31 938 (52.0) | 1393 (40.7) | 4264 (45.6) | 7238 (50.6) | 6077 (53.5) | 12 966 (56.3) | <.001 |

| Vascular risk factorse | (n = 61 006) | (n = 3389) | (n = 9255) | (n = 14 211) | (n = 11 291) | (n = 22 860) | |

| Atrial fibrillation or flutter | 17 992 (29.5) | 908 (26.8) | 2521 (27.2) | 4021 (28.3) | 3331 (29.5) | 7211 (31.5) | <.001 |

| CAD or prior MI | 18 205 (29.8) | 923 (27.2) | 2621 (28.3) | 4148 (29.2) | 3336 (29.5) | 7177 (31.4) | <.001 |

| Carotid stenosis | 2140 (3.5) | 122 (3.6) | 306 (3.3) | 478 (3.4) | 416 (3.7) | 818 (3.6) | .49 |

| Diabetes | 16 144 (26.5) | 847 (25.0) | 2398 (25.9) | 3691 (26.0) | 3002 (26.6) | 6206 (27.1) | .01 |

| Dyslipidemia | 28 223 (46.3) | 1570 (46.3) | 4319 (46.7) | 6686 (47.0) | 5240 (46.4) | 10 408 (45.5) | .06 |

| Heart failure | 6675 (10.9) | 337 (9.9) | 998 (10.8) | 1538 (10.8) | 1230 (10.9) | 2572 (11.3) | .19 |

| Hypertension | 48 063 (78.8) | 2577 (76.0) | 7240 (78.2) | 11 160 (78.5) | 8973 (79.5) | 18 113 (79.2) | <.001 |

| Peripheral artery disease | 2742 (4.5) | 128 (3.8) | 390 (4.2) | 610 (4.3) | 527 (4.7) | 1087 (4.8) | .02 |

| Prior stroke or TIA | 16 285 (26.7) | 792 (23.4) | 2265 (24.5) | 3624 (25.5) | 3076 (27.2) | 6528 (28.6) | <.001 |

| Smoker | 5423 (8.9) | 356 (10.5) | 851 (9.2) | 1321 (9.3) | 981 (8.7) | 1914 (8.4) | <.001 |

| NIHSS score, median (IQR) | 10.0 (6.0-18.0) | 11.0 (6.0-18.0) | 10.0 (6.0-17.0) | 10.0 (6.0-18.0) | 11.0 (6.0-18.0) | 11.0 (5.0-18.0) | .48 |

| Initial NIHSS scoref | (n = 57 812) | (n = 3331) | (n = 9054) | (n = 13 729) | (n = 10 665) | (n = 21 033) | |

| 0-4 | 10 371 (17.9) | 539 (16.2) | 1542 (17.0) | 2358 (17.2) | 1927 (18.1) | 4005 (19.0) | <.001 |

| 5-9 | 16 242 (28.1) | 949 (28.5) | 2693 (29.7) | 4017 (29.3) | 2960 (27.8) | 5623 (26.7) | |

| 10-14 | 10 786 (18.7) | 676 (20.3) | 1734 (19.2) | 2578 (18.8) | 1983 (18.6) | 3815 (18.1) | |

| 15-20 | 10 893 (18.8) | 636 (19.1) | 1722 (19.0) | 2604 (19.0) | 2022 (19.0) | 3909 (18.6) | |

| >20 | 9520 (16.5) | 531 (15.9) | 1363 (15.1) | 2172 (15.8) | 1773 (16.6) | 3681 (17.5) | |

| Onset-to-arrival time, median (IQR), min | 60 (40-90) | 69 (43-119) | 66 (42-108) | 63 (42-101) | 61 (41-94) | 54 (37-75) | <.001 |

| Door-to-needle time, median (IQR), min | 65 (49-88) | 25 (20-28) | 39 (36-43) | 54 (50-57) | 68 (64-72) | 96 (85-114) | <.001 |

| Onset-to-needle time, median (IQR), min | 137 (106-170) | 93 (66-144) | 105 (82-148) | 118 (95-155) | 130 (109-163) | 159 (135-180) | <.001 |

| Onset-to-needle time, min | |||||||

| <60 | 1075 (1.8) | 575 (16.8) | 371 (4.0) | 110 (0.8) | 3 (0)g | 16 (0.1)g | <.001 |

| 60-90 | 7652 (12.5) | 1084 (31.7) | 2978 (31.9) | 2748 (19.2) | 711 (6.3) | 131 (0.6) | |

| 91-120 | 14 076 (22.9) | 607 (17.8) | 2359 (25.3) | 4720 (33.0) | 3840 (33.8) | 2550 (11.1) | |

| 121-180 | 28 896 (47.0) | 810 (23.7) | 2573 (27.5) | 4971 (34.8) | 5355 (47.2) | 15 187 (66.0) | |

| 181-270 | 9727 (15.8) | 343 (10.0) | 1060 (11.3) | 1750 (12.2) | 1448 (12.7) | 5126 (22.3) | |

| Reason for tPA delay, No./total No. (%)h | |||||||

| Not documented | 7555/15 940 (47.4) | 3344/6194 (54.0) | 4211/9746 (43.2) | <.001 | |||

| Unable to determine eligibilityi | 3192/4650 (68.6) | 993/1493 (66.5) | 2199/3157 (69.7) | .03 | |||

| Hypertension requiring aggressive controli | 2498/3330 (75.0) | 962/1201 (80.1) | 1536/2129 (72.1) | <.001 | |||

| In-hospital delayj | 1666/2608 (63.9) | 704/1047 (67.2) | 962/1561 (61.6) | .003 | |||

| Hospital characteristics at patient level | |||||||

| Regional distributionk | |||||||

| South | 23 486 (38.2) | 1511 (44.2) | 3654 (39.1) | 5446 (38.1) | 4211 (37.1) | 8664 (37.7) | <.001 |

| Northeast | 14 975 (24.4) | 713 (20.9) | 2171 (23.2) | 3461 (24.2) | 2964 (26.1) | 5666 (24.6) | |

| Midwest | 11 734 (19.1) | 593 (17.3) | 1618 (17.3) | 2616 (18.3) | 2153 (19.0) | 4754 (20.7) | |

| West | 11 231 (18.3) | 602 (17.6) | 1898 (20.3) | 2776 (19.4) | 2029 (17.9) | 3926 (17.1) | |

| Rural location, No./total No. (%)l | 1818/61 376 (3.0) | 76/3419 (2.2) | 213/9338 (2.3) | 411/14 293 (2.9) | 390/11 344 (3.4) | 728/22 982 (3.2) | <.001 |

| Total No. of beds, median (IQR) | 380 (260-585) | 448 (303-659) | 417 (286-640) | 387 (262-595) | 379 (258-569) | 359 (247-539) | <.001 |

| Annual No. of ischemic stroke cases, median (IQR) | 266 (183-405) | 334 (221-467) | 308 (205-444) | 279 (189-421) | 263 (184-395) | 245 (167-368) | <.001 |

| Annual No. of cases treated with intravenous tPA, median (IQR) | 29 (18-43) | 38 (24-56) | 35 (22-50) | 31 (19-45) | 29 (17-42) | 25 (15-38) | <.001 |

| Type of facility | |||||||

| Teaching hospital, No./total No. (%)m | 47 145/60 675 (77.7) | 2763/3393 (81.4) | 7452/9248 (80.6) | 11 155/14 140 (78.9) | 8728/11 217 (77.8) | 17 047/22 677 (75.2) | <.001 |

| Primary stroke centern | 44 986 (73.2) | 2378 (69.6) | 6868 (73.5) | 10 535 (73.7) | 8342 (73.5) | 16 863 (73.3) | <.001 |

Abbreviations: CAD, coronary artery disease; IQR, interquartile range; MI, myocardial infarction; NIHSS, National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale; TIA, transient ischemic attack; tPA, tissue plasminogen activator.

Data are expressed as No. (%) unless otherwise indicated.

Based on Pearson χ2 tests for categorical variables to determine if the percentages were the same across door-to-needle times. Kruskal-Wallis tests were used for continuous variables to determine if there was a difference for at least 2 of the door-to-needle times.

Other includes Asian, American Indian/Alaskan Native, Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, mixed race, or any other nonblack or nonwhite race categories.

Defined as any other time outside 7:00 am to 6:00 pm window on any weekday, anytime during the weekend, and on national holidays. Prior studies using this prespecified time cutoff have shown that presenting during off hours was associated with inferior quality of care, inferior intravenous thrombolytic treatment, and in-hospital mortality.22,23

Calculated among patients who responded to at least 1 of the variables in the medical history panel on the data report form.

A score of 0 indicates no stroke symptoms; 1 to 4, minor stroke; 5 to 15, moderate stroke; 16 to 20, moderate to severe stroke; and greater than 20, severe stroke.

These patients did not initially present with neurological disease but developed stroke-like symptoms later; therefore, onset-to-needle time could be shorter than door-to-needle time.

Admitted during October 2012 or later.

Had 1 or more documented eligibility or medical reason for the delay.

Did not have a documented eligibility or medical reason for the delay.

Defined by the US Census Bureau. The subcategory percentages may not sum to 100 due to rounding.

Defined by the US Office of Management and Budget as areas other than metropolitan statistical areas.

Identified from American Hospital Association data.

Certified by the Joint Commission, the state’s health department, the Healthcare Facilities Accreditation Program, or Det Norske Veritas.

Most patients were treated at teaching hospitals (77.7%) and primary stroke centers (73.2%); 3% were treated at rural hospitals. More patients who were treated at teaching hospitals, but not at primary stroke centers, were treated within shorter door-to-needle times. The median door-to-needle time was 65 minutes, with 5.6% of patients treated with tPA within 30 minutes of hospital arrival, 20.8% within 45 minutes, and 44.1% within 60 minutes. The rates of data missingness for patient-level and hospital-level characteristics were low. The exceptions were missing data for National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale score (n = 3614; 5.9%) and arrival mode (n = 2774; 4.5%). There were no missing outcome data.

There was another cohort of 41 195 patients aged 65 years or older who were treated with tPA within 4.5 hours of symptom onset at GWTG-Stroke hospitals during the study period and who met the entry criteria but were excluded because they could not be matched to Medicare claims file data. Matched and unmatched patients differed substantially by age, race/ethnicity, and regional distribution but not by the other baseline characteristics (eTable 2 in the Supplement). Patients who were included in the study were slightly older than those who were excluded (median age, 80 years vs 78 years; standardized difference, 15.87). There were more non-Hispanic white patients who were included vs excluded (82.0% vs 69.7%, respectively) and fewer non-Hispanic black patients who were included vs excluded (8.7% vs 12.2%, respectively) and fewer Hispanic patients (4.0% vs 9.7%) (standardized difference, 30.86). Patients in the West region were underrepresented in the matched cohort compared with the unmatched cohort (18.3% vs 29.3%, respectively).

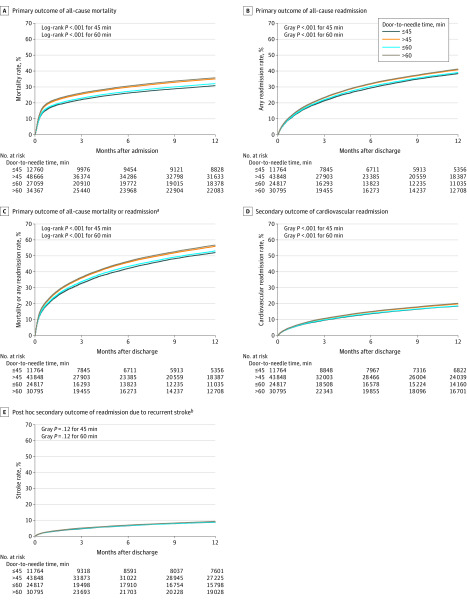

The door-to-needle time categories of within 45 minutes and within 60 minutes vs longer than these targets and the 1-year outcomes appear in Table 2. The cumulative incidence curves appear in Figure 2. Patients who received tPA after 45 minutes of hospital arrival had worse long-term outcomes than those treated within 45 minutes of hospital arrival, including significantly higher all-cause mortality (35.0% vs 30.8%, respectively; adjusted hazard ratio [HR], 1.13 [95% CI, 1.09-1.18]), higher all-cause readmission (40.8% vs 38.4%; adjusted HR, 1.08 [95% CI, 1.05-1.12]), higher all-cause mortality or readmission (56.0% vs 52.1%; adjusted HR, 1.09 [95% CI, 1.06-1.12]), and higher cardiovascular readmission (secondary outcome) (19.8% vs 18.4%; adjusted HR, 1.05 [95% CI, 1.00-1.10]), but not significantly higher recurrent stroke readmission (a post hoc secondary outcome) (9.3% vs 8.8%; adjusted HR, 1.05 [95% CI, 0.98-1.12]).

Table 2. Outcomes at 1 Year by Door-to-Needle Times of Within 45 Minutes or 60 Minutes Compared With Times Longer Than These Targets.

| Event rate | Absolute differencea | Adjusted HR (95% CI)b |

P value | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Door-to-needle time ≤45 min | Door-to-needle time >45 min | |||||||||

| No./Total No. | Uncorrected % (95% CI) |

Corrected % (95% CI) |

No./Total No. | Uncorrected % (95% CI) |

Corrected % (95% CI) |

Uncorrected % (95% CI) |

Corrected % (95% CI) |

|||

| Primary outcomes | ||||||||||

| All-cause mortality | 3933/12 760 | 30.8 (30.0 to 31.6) | 30.8 (30.0 to 31.6)c | 17 041/48 666 | 35.0 (34.6 to 35.4) | 35.0 (34.6 to 35.4)c | 4.2 (3.3 to 5.1) | 2.8 (2.0 to 3.6) | 1.13 (1.09 to 1.18) | <.001 |

| All-cause readmission | 4438/11 764 | 37.7 (36.9 to 38.6) | 38.4 (37.5 to 39.3)d | 17 633/43 848 | 40.2 (39.8 to 40.7) | 40.8 (40.4 to 41.3)d | 2.5 (1.5 to 3.5) | 2.6 (1.5 to 3.6) | 1.08 (1.05 to 1.12) | <.001 |

| All-cause mortality or readmission | 6037/11 764 | 51.3 (50.4 to 52.2) | 52.1 (51.1 to 53.0)c | 24 226/43 848 | 55.2 (54.8 to 55.7) | 56.0 (55.5 to 56.4)c | 3.9 (2.9 to 4.9) | 2.7 (1.7 to 3.6) | 1.09 (1.06 to 1.12) | <.001 |

| Secondary outcomes | ||||||||||

| Cardiovascular readmission | 2127/11 764 | 18.1 (17.4 to 18.8) | 18.4 (17.7 to 19.1)d | 8542/43 848 | 19.5 (19.1 to 19.9) | 19.8 (19.4 to 20.2)d | 1.4 (0.6 to 2.2) | 1.0 (0 to 2.0) | 1.05 (1.00 to 1.10) | .047 |

| Recurrent stroke readmissione | 1015/11 764 | 8.6 (8.1 to 9.1) | 8.8 (8.3 to 9.3)d | 3993/43 848 | 9.1 (8.8 to 9.4) | 9.3 (9.0 to 9.5)d | 0.5 (−0.1 to 1.1) | 0.5 (−0.3 to 1.2) | 1.05 (0.98 to 1.12) | .20 |

| Door-to-needle time ≤60 min | Door-to-needle time >60 min | |||||||||

| Primary outcomes | ||||||||||

| All-cause mortality | 8685/27 059 | 32.1 (31.5 to 32.7) | 32.1 (31.5 to 32.7)c | 12 289/34 367 | 35.8 (35.3 to 36.3) | 35.8 (35.3 to 36.3)c | 3.7 (2.9 to 4.4) | 2.2 (1.6 to 2.9) | 1.11 (1.07 to 1.14) | <.001 |

| All-cause readmission | 9544/24 817 | 38.5 (37.9 to 39.1) | 39.1 (38.5 to 39.7)d | 12 527/30 795 | 40.7 (40.1 to 41.2) | 41.3 (40.7 to 41.8)d | 2.2 (1.4 to 3.0) | 2.1 (1.1 to 3.0) | 1.07 (1.04 to 1.10) | <.001 |

| All-cause mortality or readmission | 12 994/24 817 | 52.4 (51.7 to 53.0) | 53.1 (52.5 to 53.8)c | 17 269/30 795 | 56.1 (55.5 to 56.6) | 56.8 (56.2 to 57.3)c | 3.7 (2.9 to 4.6) | 2.3 (1.6 to 3.1) | 1.08 (1.05 to 1.10) | <.001 |

| Secondary outcomes | ||||||||||

| Cardiovascular readmission | 4537/24 817 | 18.3 (17.8 to 18.8) | 18.6 (18.1 to 19.1)d | 6132/30 795 | 19.9 (19.5 to 20.4) | 20.2 (19.8 to 20.7)d | 1.6 (1.0 to 2.3) | 1.1 (0.3 to 2.0) | 1.06 (1.01 to 1.10) | .008 |

| Recurrent stroke readmissione | 2179/24 817 | 8.8 (8.4 to 9.1) | 8.9 (8.6 to 9.3)d | 2829/30 795 | 9.2 (8.9 to 9.5) | 9.3 (9.0 to 9.7)d | 0.4 (−0.1 to 0.9) | 0.3 (−0.3 to 0.9) | 1.03 (0.97 to 1.09) | .37 |

Abbreviation: HR, hazard ratio.

A positive value indicates a higher risk and a negative value indicates a lower risk.

The models included 56 870 patients for all-cause mortality and 51 645 patients for the readmission outcomes after excluding 4556 and 3967 patients, respectively, because of missing data on hospital characteristics and National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) score. The difference between these observations represents the number of deaths during the index hospitalization. The models adjusted for patient age, sex, race/ethnicity; vascular risk factors of atrial fibrillation or flutter, prior stroke or transient ischemic attack, history of coronary artery disease or myocardial infarction, heart failure, carotid stenosis, diabetes, peripheral artery disease, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and smoking; arrival by emergency medical services, arrival during off hours, stroke severity as measured by the NIHSS, hospital region, urban or rural location, total number of hospital beds, annual ischemic stroke volume, academic status, stroke center certification status, and the Target: Stroke initiative (using admission time before or after 2010).

The corrected event rates for all-cause mortality and the composite outcome of all-cause mortality or readmission represent cumulative incidence rates calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method.

The corrected event rates for readmission outcomes represent cumulative incidence rates calculated after adjusting for the competing risk of death.

This is a post hoc outcome and was defined as readmission for transient ischemic attack, ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke, carotid endarterectomy or stenting, but not direct complications of index stroke.

Figure 2. Cumulative Incidence Curves for 1-Year Outcomes by Door-to-Needle Time Intervals.

The number of observations was 61 426 for all-cause mortality and 55 612 for readmission outcomes. The difference between these observations represents the number of deaths during the index hospitalization.

aOf these patients, approximately 42% experienced these outcomes within 30 days.

bIncludes transient ischemic attack, ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke, carotid endarterectomy or stenting. Excludes direct complications of index stroke.

Patients who received tPA after 60 minutes of hospital arrival vs within 60 minutes of hospital arrival had significantly higher adjusted all-cause mortality (35.8% vs 32.1%, respectively; adjusted HR, 1.11 [95% CI, 1.07-1.14]), higher all-cause readmission (41.3% vs 39.1%; adjusted HR, 1.07 [95% CI, 1.04-1.10]), higher all-cause mortality or readmission (56.8% vs 53.1%; adjusted HR, 1.08 [95% CI, 1.05-1.10]), and higher cardiovascular readmission (secondary outcome) (20.2% vs 18.6%; adjusted HR, 1.06 [95% CI, 1.01-1.10]), but not significantly higher recurrent stroke readmission (a post hoc secondary outcome) (9.3% vs 8.9%; adjusted HR, 1.03 [95% CI, 0.97-1.09]).

The majority of associations between the door-to-needle times and the outcomes remained statistically significant in a sensitivity analysis limited to patients treated during 2015 and 2016. However, the association between door-to-needle time treatment within 60 minutes and the secondary outcome of cardiovascular readmission was no longer statistically significant (eTable 3 in the Supplement).

The outcomes by door-to-needle times in 45-minute and 60-minute increments appear in eTable 4 and eTable 5 in the Supplement. The absolute differences in outcomes increased with longer door-to-needle times. The cumulative incidence curves showed that approximately 42% of the deaths or readmissions occurred within 30 days.

Long-term outcomes by door-to-needle times in 15-minute increments appear in Table 3, along with the absolute differences and the unadjusted and adjusted HRs from the Cox proportional hazard models. The spline plots in the eFigure in the Supplement graphically illustrate nonlinear associations of door-to-needle times with 1-year mortality, cardiovascular readmission, and recurrent stroke readmission.

Table 3. Outcomes at 1 Year by Door-to-Needle Times in 15-Minute Increments.

| Door-to-needle time, min | Within 90 mina | After 90 mina | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤30 | 31-45 | 46-60 | 61-75 | >75 | |||

| All-cause mortality | |||||||

| Event rate | |||||||

| No./total No. | 1087/3419 | 2846/9341 | 4752/14 299 | 3968/11 357 | 8321/23 010 | ||

| Uncorrected % (95% CI) | 31.8 (30.3 to 33.4) | 30.5 (29.5 to 31.4) | 33.2 (32.5 to 34.0) | 34.9 (34.1 to 35.8) | 36.2 (35.5 to 36.8) | ||

| Corrected % (95% CI)b | 31.8 (30.3 to 33.4) | 30.5 (29.5 to 31.4) | 33.2 (32.5 to 34.0) | 34.9 (34.1 to 35.8) | 36.2 (35.5 to 36.8) | ||

| Absolute differencec | |||||||

| Uncorrected % (95% CI) | 1 [Reference] | −1.3 (−3.1 to 0.5) | 1.4 (−0.3 to 3.2) | 3.1 (1.4 to 4.9) | 4.4 (2.7 to 6.0) | ||

| Corrected % (95% CI) | 1 [Reference] | −1.2 (−2.7 to 0.4) | 1.0 (−0.5 to 2.5) | 1.9 (0.4 to 3.4) | 2.7 (1.2 to 4.1) | ||

| Unadjusted hazard ratio (95% CI) | 1 [Reference] | 0.95 (0.88 to 1.02) | 1.06 (0.98 to 1.14) | 1.11 (1.03 to 1.20) | 1.17 (1.08 to 1.25) | 1.06 (1.04 to 1.07) | 0.98 (0.97 to 1.00) |

| P value | .16 | .14 | .007 | <.001 | <.001 | .03 | |

| Adjusted hazard ratio (95% CI)d | 1 [Reference] | 0.95 (0.88 to 1.02) | 1.05 (0.97 to 1.13) | 1.09 (1.01 to 1.18) | 1.13 (1.05 to 1.21) | 1.04 (1.02 to 1.05) | 1.01 (0.99 to 1.03) |

| P value | .17 | .25 | .03 | .001 | <.001 | .27 | |

| All-cause readmission | |||||||

| Event rate | |||||||

| No./total No. | 1182/3133 | 3256/8631 | 5106/13 053 | 4104/10 261 | 8423/20 534 | ||

| Uncorrected % (95% CI) | 37.7 (36.0 to 39.4) | 37.7 (36.7 to 38.8) | 39.1 (38.3 to 40.0) | 40.0 (39.1 to 40.9) | 41.0 (40.4 to 41.7) | ||

| Corrected % (95% CI)e | 38.4 (36.7 to 40.2) | 38.3 (37.3 to 39.4) | 39.8 (39.0 to 40.7) | 40.6 (39.7 to 41.6) | 41.6 (40.9 to 42.3) | ||

| Absolute differencec | |||||||

| Uncorrected, % (95% CI) | 1 [Reference] | 0 (−2.0 to 2.0) | 1.4 (−0.5 to 3.3) | 2.3 (0.3 to 4.2) | 3.3 (1.5 to 5.1) | ||

| Corrected % (95% CI) | 1 [Reference] | −0.7 (−2.8 to 1.5) | 1.2 (−0.8 to 3.3) | 1.9 (−0.3 to 4.0) | 2.8 (0.8 to 4.8) | ||

| Unadjusted HR (95% CI) | 1 [Reference] | 0.99 (0.92 to 1.06) | 1.05 (0.99 to 1.12) | 1.09 (1.02 to 1.17) | 1.14 (1.07 to 1.21) | 1.02 (1.02 to 1.03) | |

| P value | .75 | .10 | .009 | <.001 | <.001 | ||

| Adjusted hazard ratio (95% CI)d | 1 [Reference] | 0.98 (0.91 to 1.05) | 1.04 (0.97 to 1.11) | 1.06 (0.99 to 1.14) | 1.09 (1.02 to 1.17) | 1.02 (1.01 to 1.03) | |

| P value | .54 | .24 | .10 | .007 | <.001 | ||

| All-cause mortality or readmission | |||||||

| Event rate | |||||||

| No./total No. | 1598/3133 | 4439/8631 | 6957/13 053 | 5653/10 261 | 11 616/20 534 | ||

| Uncorrected % (95% CI) | 51.0 (49.3 to 52.8) | 51.4 (50.4 to 52.5) | 53.3 (52.4 to 54.2) | 55.1 (54.1 to 56.1) | 56.6 (55.9 to 57.3) | ||

| Corrected % (95% CI)b | 51.8 (50.0 to 53.6) | 52.1 (51.1 to 53.2) | 54.1 (53.2 to 55.0) | 55.8 (54.8 to 56.8) | 57.2 (56.6 to 57.9) | ||

| Absolute differencec | |||||||

| Uncorrected % (95% CI) | 1 [Reference] | 0.4 (−1.6 to 2.5) | 2.3 (0.3 to 4.2) | 4.1 (2.1 to 6.1) | 5.6 (3.7 to 7.4) | ||

| Corrected % (95% CI) | 1 [Reference] | −0.2 (−2.0 to 1.6) | 1.5 (−0.3 to 3.2) | 2.3 (0.6 to 4.1) | 3.5 (1.8 to 5.2) | ||

| Unadjusted hazard ratio (95% CI) | 1 [Reference] | 1.00 (0.94 to 1.06) | 1.06 (1.01 to 1.13) | 1.11 (1.04 to 1.17) | 1.16 (1.09 to 1.22) | 1.02 (1.02 to 1.03) | |

| P value | .96 | .03 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | ||

| Adjusted hazard ratio (95% CI)d | 1 [Reference] | 0.99 (0.93 to 1.06) | 1.05 (0.99 to 1.11) | 1.08 (1.01 to 1.15) | 1.12 (1.05 to 1.18) | 1.02 (1.01 to 1.03) | |

| P value | .85 | .12 | .02 | <.001 | <.001 | ||

| Cardiovascular readmission | Within 60 min | After 60 min | |||||

| Event rate | |||||||

| No./total No. | 568/3133 | 1559/8631 | 2410/13 053 | 1970/10 261 | 4162/20 534 | ||

| Uncorrected % (95% CI) | 18.1 (16.8 to 19.5) | 18.1 (17.3 to 18.9) | 18.5 (17.8 to 19.1) | 19.2 (18.4 to 20.0) | 20.3 (19.7 to 20.8) | ||

| Corrected % (95% CI)e | 18.5 (17.2 to 19.9) | 18.4 (17.6 to 19.2) | 18.8 (18.2 to 19.5) | 19.5 (18.7 to 20.3) | 20.6 (20.0 to 21.2) | ||

| Absolute differencec | |||||||

| Uncorrected % (95% CI) | 1 [Reference] | −0.1 (−1.6 to 1.5) | 0.3 (−1.2 to 1.8) | 1.1 (−0.5 to 2.6) | 2.1 (0.7 to 3.6) | ||

| Corrected % (95% CI) | 1 [Reference] | −0.3 (−2.3 to 1.6) | 0.1 (−1.8 to 2.0) | 0.5 (−1.4 to 2.4) | 1.4 (−0.4 to 3.2) | ||

| Unadjusted hazard ratio (95% CI) | 1 [Reference] | 1.00 (0.91 to 1.11) | 1.04 (0.94 to 1.14) | 1.09 (0.99 to 1.20) | 1.16 (1.06 to 1.27) | 1.04 (1.01 to 1.08) | 1.03 (1.01 to 1.04) |

| P value | .98 | .43 | .09 | .002 | .009 | <.001 | |

| Adjusted hazard ratio (95% CI)d | 1 [Reference] | 0.98 (0.89 to 1.08) | 1.01 (0.91 to 1.11) | 1.02 (0.93 to 1.13) | 1.07 (0.97 to 1.17) | 1.01 (0.98 to 1.05) | 1.02 (1.01 to 1.04) |

| P value | .72 | .91 | .62 | .15 | .42 | <.001 | |

| Recurrent stroke readmissionf | |||||||

| Event rate | |||||||

| No./total No. | 284/3133 | 731/8631 | 1164/13 053 | 918/10 261 | 1911/20 534 | ||

| Uncorrected % (95% CI) | 9.1 (8.1 to 10.1) | 8.5 (7.9 to 9.1) | 8.9 (8.4 to 9.4) | 8.9 (8.4 to 9.5) | 9.3 (8.9 to 9.7) | ||

| Corrected % (95% CI)e | 9.2 (8.3 to 10.3) | 8.6 (8.0 to 9.2) | 9.1 (8.6 to 9.6) | 9.1 (8.5 to 9.7) | 9.4 (9.0 to 9.9) | ||

| Absolute differenced | |||||||

| Uncorrected % (95% CI) | 1 [Reference] | −0.6 (−1.8 to 0.6) | −0.1 (−1.3 to 1.0) | −0.1 (−1.3 to 1.0) | 0.2 (−0.8 to 1.3) | ||

| Corrected % (95% CI) | 1 [Reference] | −0.7 (−2.1 to 0.8) | −0.1 (−1.5 to 1.3) | −0.3 (−1.7 to 1.2) | 0.2 (−1.2 to 1.5) | ||

| Unadjusted hazard ratio (95% CI) | 1 [Reference] | 0.94 (0.82 to 1.09) | 1.01 (0.89 to 1.15) | 1.01 (0.89 to 1.15) | 1.07 (0.94 to 1.21) | 1.01 (0.97 to 1.06) | 1.03 (1.01 to 1.04) |

| P value | .42 | .89 | .87 | .32 | .62 | .008 | |

| Adjusted hazard ratio (95% CI)d | 1 [Reference] | 0.94 (0.82 to 1.08) | 0.99 (0.87 to 1.13) | 0.97 (0.85 to 1.11) | 1.01 (0.89 to 1.15) | 0.99 (0.95 to 1.04) | 1.02 (1.00 to 1.04) |

| P value | .36 | .91 | .70 | .83 | .76 | .03 | |

The cutoff values were derived from nonlinear distribution as shown in the spline plots. The absence of cutoff times for all-cause readmission and the composite of all-cause mortality or readmission was because these 2 outcomes showed linear distribution in relation to door-to-needle times in 15-minute increments within 4.5 hours of time last known to be well.

The corrected event rates for all-cause mortality and the composite outcome of all-cause mortality or readmission represent cumulative incidence rates calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method.

A positive value indicates a higher risk and a negative value indicates a lower risk.

The models included 56 870 patients for all-cause mortality and 51 645 patients for the readmission outcomes after excluding 4556 and 3967 patients, respectively, because of missing data on hospital characteristics and National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) score. The difference between these observations represents the number of deaths during the index hospitalization. The models adjusted for patient age, sex, race/ethnicity; vascular risk factors of atrial fibrillation or flutter, prior stroke or transient ischemic attack, history of coronary artery disease or myocardial infarction, heart failure, carotid stenosis, diabetes, peripheral artery disease, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and smoking; arrival by emergency medical services, arrival during off hours, stroke severity as measured by the NIHSS, hospital region, urban or rural location, total number of hospital beds, annual ischemic stroke volume, academic status, stroke center certification status, and the Target: Stroke initiative (using admission time before or after 2010).

The corrected event rates for readmission outcomes represent cumulative incidence rates calculated after adjusting for the competing risk of death.

Recurrent stroke readmission, a post hoc outcome, was defined as readmission for transient ischemic attack, ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke, carotid endarterectomy or stenting, but not direct complications of index stroke.

Every 15-minute increase in door-to-needle times was significantly associated with higher all-cause mortality (adjusted HR, 1.04 [95% CI, 1.02-1.05] for door-to-needle time within 90 minutes of arrival, which is a cut point derived from the spline plot). However, this association did not persist beyond 90 minutes of hospital arrival. Every 15-minute increase in door-to-needle times was significantly associated with higher all-cause readmission (adjusted HR, 1.02 [95% CI, 1.01-1.03]) and higher all-cause mortality or readmission (adjusted HR, 1.02 [95% CI, 1.01-1.03]). Every 15-minute increase in door-to-needle times after 60 minutes of hospital arrival was significantly associated with higher cardiovascular readmission (secondary outcome) (adjusted HR, 1.02 [95% CI, 1.01-1.04]) and higher stroke readmission (a post hoc secondary outcome) (adjusted HR, 1.02 [95% CI, 1.00-1.04]); however, these associations were not statistically significant for the door-to-needle times within 60 minutes of hospital arrival.

The sensitivity analysis of patients treated during 2015 and 2016 confirmed the associations with the outcomes during the most contemporary period (eTable 6 in the Supplement).

Discussion

This nationwide study of older US patients treated with intravenous tPA for acute ischemic stroke in GWTG-Stroke hospitals demonstrated that shorter door-to-needle times for tPA administration were significantly associated with better long-term outcomes, including lower 1-year all-cause mortality, 1-year all-cause readmission, and the composite of all-cause mortality or readmission at 1 year.

Patients who received intravenous tPA with door-to-needle times within 45 minutes had the lowest mortality and readmission rates, followed by door-to-needle times within 60 minutes. When patients were stratified by door-to-needle times that were within 45 minutes or 60 minutes, shorter door-to-needle times were consistently associated with better outcomes, suggesting that these findings were not just the result of an outlier association.

Every 15-minute increase in door-to-needle time up to 90 minutes was significantly associated with worse 1-year outcomes. However, a door-to-needle time within 30 minutes was not significantly associated with even better outcomes. Overall, these findings further support local and national efforts for improving door-to-needle times for thrombolytic therapy.7,8,9

The Target: Stroke initiative was launched in 2010 to assist hospitals in providing tPA in a timely fashion.7,8 As a result, the proportion of tPA administered within 60 minutes increased from 26.5% during the preintervention period to 41.3% during the postintervention period.9 The lower rates of mortality and readmission associated with shorter door-to-needle times in the current study support calls for continuous implementation of these strategies to reduce delay in tPA administration to parallel the success that has been achieved with shorter door-to-balloon times for percutaneous coronary intervention.28,29

These data are consonant with and extend the results of prior studies. The 2 randomized trials that have assessed long-term outcomes found that allocation to intravenous tPA compared with control reduced disability 1 to 1.5 years after stroke.3,4 In contrast, lower long-term mortality rates with intravenous tPA did not reach statistical significance.3,4 However, the power of these trials to probe for mortality effects was limited by modest sample sizes. The current study, an order of magnitude larger in size, has substantially more power and found statistically significant lower long-term mortality associated with faster intravenous thrombolytic treatment.

A prior study of the GWTG-Stroke registry found that faster onset-to-treatment time with intravenous tPA was associated with improved short-term in-hospital outcomes, including lower in-hospital mortality, lower symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage, and higher likelihood of independent ambulation.6 However, that study did not investigate the association of door-to-needle times with postdischarge outcomes.

The current study found that accelerated door-to-needle times, specifically within 45 minutes and 60 minutes, were significantly associated with better outcomes including 1-year all-cause mortality, 1-year all-cause readmission, the composite of all-cause mortality or readmission at 1 year, and cardiovascular readmission through 1 year. It is possible that better neurological function after discharge and at 3 months with shorter door-to-needle times have enabled physical activity and a healthier lifestyle resulting in lower cardiovascular events and readmissions.1,5,6,30,31

A door-to-needle time within 30 minutes was not associated with even better outcomes. This lack of association needs to be further investigated, although the analyses may be underpowered for this group (5.6% of total patients). Door-to-needle times were not consistently associated with recurrent stroke readmission, which is in line with trial results finding no effect of tPA administration on stroke recurrence.32

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, data on patient characteristics and treatment time intervals were manually recorded and self-reported by the participating hospitals, although prior quality audits of GWTG-Stroke data showed high concordance rates with source documentation.11

Second, to obtain long-term outcomes, this study included fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries aged 65 years or older who were treated at GWTG-Stroke participating hospitals, with complete data linked in these 2 databases. Previous work has demonstrated that patients in the database that links GWTG-Stroke and Medicare data are representative of the national Medicare population with ischemic stroke.18 However, the results may not be applicable to patients who experience stroke at a younger age.

Third, a prior study of GWTG-Stroke showed that 3.5% of tPA treatments were given to patients who were later classified as not having had an acute ischemic stroke.33 Patients with stroke mimic events were excluded from the current study.

Fourth, 8195 patients (13%) were excluded from the matched population because of missing data on disposition, onset-to-treatment time, or door-to-needle time, which may generate selection bias.

Fifth, rural and minority populations and the West region were underrepresented, which may affect the generalizability of the results.

Sixth, although the outcome analyses adjusted for multiple patient-level and hospital-level baseline characteristics, there might be residual measured and unmeasured confounding including hospital resources that may influence door-to-needle times and outcomes.

Seventh, cost information and other patient-centered outcomes, including quality-of-life and functional outcomes, were not examined.

Eighth, the modest association should be taken into consideration when interpreting the clinical relevance, not merely the statistical significance.

Ninth, the study was limited to patients treated with intravenous tPA within 4.5 hours of the time they were last known to be well and may not be applicable to thrombolytic therapy for stroke with unknown time of symptom onset or stroke events at time of waking up. Magnetic resonance imaging or computerized tomography perfusion scans are needed in these cases to determine patient eligibility for treatment as demonstrated in the recent studies.34,35

Tenth, the cause of death was not studied because Medicare files do not contain this information.

Conclusions

Among patients aged 65 years or older with acute ischemic stroke who were treated with tissue plasminogen activator, shorter door-to-needle times were associated with lower all-cause mortality and lower all-cause readmission at 1 year. These findings support efforts to shorten time to thrombolytic therapy.

eFigure. Spline plots of one-year outcomes in relationship to door-to-needle times

eTable 1. Patient and hospital characteristics by door-to-needle times of 45 minutes and 60 minutes

eTable 2. Comparison of patient characteristics of included and excluded population

eTable 3. Sensitivity analysis: outcomes at one year by door-to-needle times of 45 minutes and 60 minutes in 2015 and 2016

eTable 4. Outcomes at one year by door-to-needle time in 60-minute increments

eTable 5. Outcomes at one year by door-to-needle time in 45-minute increments

eTable 6. Sensitivity analysis: outcomes at one year by door-to-needle times in 15-minute increments in 2015 and 2016

References

- 1.Emberson J, Lees KR, Lyden P, et al. ; Stroke Thrombolysis Trialists’ Collaborative Group . Effect of treatment delay, age, and stroke severity on the effects of intravenous thrombolysis with alteplase for acute ischaemic stroke: a meta-analysis of individual patient data from randomised trials. Lancet. 2014;384(9958):1929-1935. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60584-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wardlaw JM, Murray V, Berge E, del Zoppo GJ. Thrombolysis for acute ischaemic stroke. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;(7):CD000213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.IST-3 Collaborative Group Effect of thrombolysis with alteplase within 6 h of acute ischaemic stroke on long-term outcomes (the third International Stroke Trial [IST-3]): 18-month follow-up of a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12(8):768-776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kwiatkowski TG, Libman RB, Frankel M, et al. ; National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke Recombinant Tissue Plasminogen Activator Stroke Study Group . Effects of tissue plasminogen activator for acute ischemic stroke at one year. N Engl J Med. 1999;340(23):1781-1787. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199906103402302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lansberg MG, Schrooten M, Bluhmki E, Thijs VN, Saver JL. Treatment time-specific number needed to treat estimates for tissue plasminogen activator therapy in acute stroke based on shifts over the entire range of the modified Rankin Scale. Stroke. 2009;40(6):2079-2084. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.540708 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Saver JL, Fonarow GC, Smith EE, et al. Time to treatment with intravenous tissue plasminogen activator and outcome from acute ischemic stroke. JAMA. 2013;309(23):2480-2488. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.6959 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xian Y, Xu H, Lytle B, et al. Use of strategies to improve door-to-needle times with tissue-type plasminogen activator in acute ischemic stroke in clinical practice: findings from Target: Stroke. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2017;10(1):e003227. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.116.003227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fonarow GC, Smith EE, Saver JL, et al. Improving door-to-needle times in acute ischemic stroke: the design and rationale for the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association’s Target: Stroke initiative. Stroke. 2011;42(10):2983-2989. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.621342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fonarow GC, Zhao X, Smith EE, et al. Door-to-needle times for tissue plasminogen activator administration and clinical outcomes in acute ischemic stroke before and after a quality improvement initiative. JAMA. 2014;311(16):1632-1640. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.3203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fonarow GC, Reeves MJ, Smith EE, et al. ; GWTG-Stroke Steering Committee and Investigators . Characteristics, performance measures, and in-hospital outcomes of the first one million stroke and transient ischemic attack admissions in Get With The Guidelines-Stroke. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2010;3(3):291-302. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.109.921858 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xian Y, Fonarow GC, Reeves MJ, et al. Data quality in the American Heart Association Get With The Guidelines-Stroke (GWTG-Stroke): results from a national data validation audit. Am Heart J. 2012;163(3):392-398, 398.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2011.12.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schwamm LH, Reeves MJ, Pan W, et al. Race/ethnicity, quality of care, and outcomes in ischemic stroke. Circulation. 2010;121(13):1492-1501. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.881490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johnston SC, Fung LH, Gillum LA, et al. Utilization of intravenous tissue-type plasminogen activator for ischemic stroke at academic medical centers: the influence of ethnicity. Stroke. 2001;32(5):1061-1068. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.32.5.1061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Therrien M, Ramirez RR The Hispanic population in the United States: population characteristics helping you make informed decisions: 2001. Accessed January 20, 2020. https://cps.ipums.org/cps/resources/cpr/p20-535.pdf

- 15.Protection of human subjects. 45 CFR part 690 and 49 CFR part 11.

- 16.Hammill BG, Hernandez AF, Peterson ED, Fonarow GC, Schulman KA, Curtis LH. Linking inpatient clinical registry data to Medicare claims data using indirect identifiers. Am Heart J. 2009;157(6):995-1000. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2009.04.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schoen Bandeali D. Medicare: 50 years of ensuring coverage and care. Accessed November 16, 2019. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/fund-reports/2015/apr/medicare-50-years-ensuring-coverage-and-care

- 18.Reeves MJ, Fonarow GC, Smith EE, et al. Representativeness of the Get With The Guidelines-Stroke Registry: comparison of patient and hospital characteristics among Medicare beneficiaries hospitalized with ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2012;43(1):44-49. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.626978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Austin PC. Balance diagnostics for comparing the distribution of baseline covariates between treatment groups in propensity-score matched samples. Stat Med. 2009;28(25):3083-3107. doi: 10.1002/sim.3697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Smith EE, Saver JL, Cox M, et al. Increase in endovascular therapy in Get With The Guidelines-Stroke after the publication of pivotal trials. Circulation. 2017;136(24):2303-2310. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.031097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fonarow GC, Pan W, Saver JL, et al. Comparison of 30-day mortality models for profiling hospital performance in acute ischemic stroke with vs without adjustment for stroke severity. JAMA. 2012;308(3):257-264. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.7870 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reeves MJ, Smith E, Fonarow G, Hernandez A, Pan W, Schwamm LH; GWTG-Stroke Steering Committee & Investigators . Off-hour admission and in-hospital stroke case fatality in the Get With The Guidelines-Stroke program. Stroke. 2009;40(2):569-576. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.519355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Messé SR, Khatri P, Reeves MJ, et al. Why are acute ischemic stroke patients not receiving IV tPA? results from a national registry. Neurology. 2016;87(15):1565-1574. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000003198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fonarow GC, Smith EE, Saver JL, et al. Timeliness of tissue-type plasminogen activator therapy in acute ischemic stroke: patient characteristics, hospital factors, and outcomes associated with door-to-needle times within 60 minutes. Circulation. 2011;123(7):750-758. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.974675 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smith EE, Shobha N, Dai D, et al. A risk score for in-hospital death in patients admitted with ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke. J Am Heart Assoc. 2013;2(1):e005207. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.112.005207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Smith EE, Shobha N, Dai D, et al. Risk score for in-hospital ischemic stroke mortality derived and validated within the Get With The Guidelines-Stroke Program. Circulation. 2010;122(15):1496-1504. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.932822 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Poythress JC, Lee MY, Young J. Planning and analyzing clinical trials with competing risks: recommendations for choosing appropriate statistical methodology. Pharm Stat. 2020;19(1):4-21. doi: 10.1002/pst.1966 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.O’Gara PT, Kushner FG, Ascheim DD, et al. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of ST-elevation myocardial infarction: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61(4):485-510. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.11.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ibanez B, James S, Agewall S, et al. 2017 ESC guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation: the task force for the management of acute myocardial in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2018;39(2):119-177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Franco OH, de Laet C, Peeters A, Jonker J, Mackenbach J, Nusselder W. Effects of physical activity on life expectancy with cardiovascular disease. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165(20):2355-2360. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.20.2355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lanier JB, Bury DC, Richardson SW. Diet and physical activity for cardiovascular disease prevention. Am Fam Physician. 2016;93(11):919-924. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Johnston SC, Easton JD. Are patients with acutely recovered cerebral ischemia more unstable? Stroke. 2003;34(10):2446-2450. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000090842.81076.68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ali-Ahmed F, Federspiel JJ, Liang L, et al. Intravenous tissue plasminogen activator in stroke mimics. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2019;12(8):e005609. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.119.005609 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nogueira RG, Jadhav AP, Haussen DC, et al. ; DAWN Trial Investigators . Thrombectomy 6 to 24 hours after stroke with a mismatch between deficit and infarct. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(1):11-21. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1706442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ma H, Campbell BCV, Parsons MW, et al. ; EXTEND Investigators . Thrombolysis guided by perfusion imaging up to 9 hours after onset of stroke. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(19):1795-1803. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1813046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eFigure. Spline plots of one-year outcomes in relationship to door-to-needle times

eTable 1. Patient and hospital characteristics by door-to-needle times of 45 minutes and 60 minutes

eTable 2. Comparison of patient characteristics of included and excluded population

eTable 3. Sensitivity analysis: outcomes at one year by door-to-needle times of 45 minutes and 60 minutes in 2015 and 2016

eTable 4. Outcomes at one year by door-to-needle time in 60-minute increments

eTable 5. Outcomes at one year by door-to-needle time in 45-minute increments

eTable 6. Sensitivity analysis: outcomes at one year by door-to-needle times in 15-minute increments in 2015 and 2016