Abstract

Background

The suicide of minors in Germany is rare in absolute numbers: there were only 212 suicides among persons aged 10 to 20 in Germany in 2017. Nonetheless, in school surveys, 36.4–39.4% of those surveyed reported suicidal ideation, and 6.5–9% reported suicide attempts. Suicide among children and adolescents is thus a clinically and societally relevant problem.

Methods

This review is based on pertinent articles retrieved by a selective literature search in the PubMed and PsycInfo databases (April 2019) employing the search terms “suicidality,” “suicidal*,” and “suicide,” and on further information from several textbooks (1991–2017).

Results

In children and adolescents with a mental illness, the risk of suicide is higher by a factor of 3 to 12. Mobbing experiences increase the suicide risk as well (odds ratio [OR] = 2.21, p <0.05). Non-suicidal self-injurious behavior (NSSB) is also a risk factor for both suicidal ideation (OR = 2.95) and suicide attempts (hazard ratio [HR] = 2.00). Intoxication with medications is the most common method of attempted suicide (67.7%). Most suicides are preceded by early warning signs. Psychiatric hospitalization is indicated for children and adolescents who are in acute danger of doing harm to themselves. Specific types of treatment, family-centered methods in particular, have been found to lessen the frequency of suicidal ideation and suicide attempts. The administration of antidepressant drugs to children and adolescents is controversial, as there is evidence of increased suicidality (but not mortality) for single medications. Antidepressant drugs should not, however, be withheld for this reason, if indicated. The prerequisite in all cases is close observation.

Conclusion

To prevent suicide and improve outcomes, risk factors for suicide must be considered, and the indications for primary and secondary preventive and therapeutic measures must be established. Online therapeutic modalities may become more widely used in the near future, particularly among young patients, who are well versed in the use of the Internet.

In Germany in the year 2017, 184 adolescents and young adults between 15 and 20 years of age took their own lives. A further 28 persons who committed suicide were 10 to 15 years old (1). In absolute terms, suicide in the age group 10–20 years (212 cases in 2017) is rarer than in older adults (e.g., 50–60 years: 1958 cases in 2017). The danger should not be underestimated, however; suicidal thoughts and suicide attempts are common among adolescents. In German school samples, 36.4–39.4% of the students questioned reported suicidal thoughts and 6.5–9.0% had made at least one suicide attempt (2, 3). The findings did not differ significantly from those in a population of school students in the USA (2). In a German study, 25.6% of a group of 13- to 25-year-olds receiving inpatient psychiatric treatment reported a suicide attempt in the past (4). Suicidality thus occurs in young people with and without underlying psychiatric illness.

Although not every case constitutes acute self-endangerment or a psychiatric emergency, it is vital to provide professional care to those seeking help. Basic familiarity with how best to manage risk groups is relevant not only for specialized psychiatric personnel, but also for all members of the medical, therapeutic, nursing, and teaching professions who work with children and adolescents.

Method

This review of suicidality in childhood and adolescence is based on a survey of the literature in PubMed/PsycINFO in April 2019 using the search terms “suicidality”, “suicidal*”, and “suicide.” Furthermore, a number of textbooks published between 1991 and 2017 were scrutinized. We focus on the definition, epidemiology, etiology, risk factors, diagnosis, and guideline-oriented treatment of suicidality in childhood and adolescence.

Definition

The term suicidality embraces suicidal thoughts, plans, and actions, suicide attempts, and completed suicide (5). The spectrum of suicidal thoughts among the young is broad, ranging from occasionally thinking that life is no longer worth living to actively considering suicide (5, 6). A suicide plan exists when the young person has already decided on concrete methods (7). A suicide attempt is any self-initiated behavior which, at the time of action, is designed to lead to death (8). This means, for example, that the intake of substances that an adult would not consider harmful (e.g., large amounts of contraceptive pills) in the expectation of a fatal outcome also counts as a suicide attempt. Self-harming actions not intended to end in death must be distinguished from suicidality (9). Such actions include, for instance, tests of courage and—relatively widespread among minors—non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI), which frequently serves to regulate aversive emotional states (10). Tragic deaths such as those resulting from psychotic misconceptions or organ failure in anorexia nervosa without the intention of dying do not count as suicide (9). However, it may be difficult to classify individual deaths as suicide or otherwise.

The different degrees of severity of suicide attempts are described in Box 1 (9). This classification of severity is, however, controversial, as a strong wish to die may underlie an objectively non-life-threatening action (9). Seven percent of adolescents who undergo medical treatment after a suicide attempt, regardless of its severity, try to kill themselves again. Among those who have already made two or more suicide attempts, 24% try again (11).

Epidemiology

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), suicide is one of the greatest health problems worldwide (12). In western countries, suicide is the second or third most common cause of death in adolescence (13). The suicide statistics in Germany follow the “Hungarian” pattern, i.e., the rate of suicide is much higher in old age than in youth (14). In 2017, men accounted for 76% of suicides in Germany (1). In contrast to completed suicides, girls and young women (14–24 years) are overrepresented with regard to suicidal thoughts (odds ratio [OR] = 1.7; p <0.001) and suicide attempts (OR = 1.7; p <0.5) (15). A Swiss study of suicidal minors found that more boys than girls killed themselves. The boys used “hard” methods (e.g., hanging) significantly more often than the girls (16). A German study in adults came to similar conclusions (17).

Considering male and female suicide attempts together, the most frequently used method is poisoning with drugs (67.7%). However, this method was associated with the lowest rate of death in the aforementioned study in Switzerland (4.7% versus 77.9% for guns, 77.1% for hanging, etc.) (16). Suicide attempts and completed suicide are extremely rare in younger children (no cases of suicide in children <10 years in Germany in 2017), who do not usually possess the cognitive maturity required for the preparation of a “successful” suicide attempt (1).

Etiology and risk factors

Adolescents in suicidal crises perceive their room for maneuver as extremely limited. The notion that they can decide whether to live or die can have a temporary liberating effect. The “presuicidal syndrome” described by Ringel in 1953 (18) refers to a possible suicidal decision chain and defines various components, including inhibited aggression turned against the self. Many young people in suicidal crises are ambivalent to the last (19). Although their actions are intended to end their life, they are actually striving for another life (5). According to Joiner, the interaction of the following three factors represents a risk constellation for suicide (20):

The feeling of social alienation

The feeling of being a burden to others

The acquired ability to enact self-injury

Particular warning signs may point to the development of suicidality in minors (Box 2) (21, 22). However, few suicides are planned carefully far in advance. Especially young people are prone to act impulsively (5).

BOX 2. Warning signs and risk factors for suicidality in childhood and adolescence.

-

Sudden change in behavior

Apathy

Withdrawal

Unusual preoccupation with dying or death

Giving away personal possessions

Symptoms of depression, basic unhappiness

Mood fluctuation, elevated emotional lability

Distinct hopelessness

Distinct feelings of guilt and self-reproach

Expression of altruistic ideas of suicide or self-sacrifice

Severe sleep disturbances

Recent experience of loss

Acute or chronic traumatization

-

Risk factors*

Mental illness: in particular, depressive disorder and bipolar disorders, acute psychotic disorder (especially with imperative acoustic hallucinations), post-traumatic stress disorder (23), dependency diseases, bulimia nervosa, attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder, anxiety disorders, disordered social behavior with elevated impulsiveness, personality disorders with elevated impulsiveness, delinquency (22, 31, 32)

Conflict, separation, or divorce of parents, loss of a parent, or a history of sexual abuse/maltreatment (24, 34)

Performance problems at school (35)

Chronic organic illness and physical disability (22)

Low socioeconomic status (36)

* We have attempted to list the risk factors in order of importance. In clinical practice, the number of risk factors and one’s situative assessment of acute suicidality are crucial in determining the degree of danger and deciding on the appropriate preventive measures.

One risk group is adolescents with mental illness; they have a 3- to 12-fold higher risk of suicide (22). In acute intoxication, the substance-related reduction in critical faculties and weakening of inhibition increase the suicide risk. In adolescents with borderline personality development disorders, chronic or repetitive suicidality may be a component part of the syndrome (22). A German/Swiss study of adolescents and young adults showed that 93.4% of suicide attempts in this population were preceded by post-traumatic stress disorder. The authors concluded that these attempts at suicide might have been prevented by adequate treatment of the post-traumatic stress disorder (23). Young people with NSSI are more likely to have suicidal thoughts (OR = 2.95) (24) and to attempt to kill themselves (hazard ratio [HR] = 2.00) (25). Mobbing also increases the risk of suicide (OR = 2.21; p <0.05) (26, 27). Previous suicide attempts constitute one of the most important predictors of completed suicide (28, 29). However, the low sensitivity and specificity of the risk factors makes it difficult to predict future suicidal behavior (30).

Additional risks, particularly to minors, may arise from social media and internet use (box 3).

BOX 3. Suicidality and internet communication.

Suicidality comes to the attention of children and adolescents not so much through journalism as through frequently deficient internet-based communication. Particularly the young are susceptible to imitation effects. One of a number of exhaustive reading lists on this topic was provided by the German Society for Prevention of Suicide (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Suizidprävention) in 2006 (37). An example of the responsibilities media have and the different ways they deal with them was provided by the “Blue Whale Challenge”—a web-based “test of courage” comprising a series of 50 tasks. Participants were encouraged to perform risky and/or self-harming acts of increasing intensity, the last of them being suicide. The existence of the Blue Whale Challenge remains controversial, but it was discussed in media worldwide (38).

Children and adolescents in suicidal crises may be endangered by offensive posts on social media or websites providing concrete information on how to obtain the means of committing suicide. Critics emphasize that hopelessness can be reinforced and at the same time the seeking of professional help can be hindered (39). On the other hand, those looking for assistance online can encounter not only condemnation, but also sympathy. The communication—sometimes anonymously—of feelings and fantasies can relieve the pressure to perform suicidal acts and open a path towards controlled and protected contact with other people (39). One positive example of web-based suicide prevention is the information platform www.klicksafe.de, a European Union initiative for higher safety on the internet. This website offers advice for parents and teachers on how to deal with suicidal pronouncements on the internet and in concrete risk situations (40). A second positive example is the “U25” e-mail counseling service of the charity Caritas, where young people in suicidal crises are advised anonymously and free of charge by “peers,” i.e., professionally trained counselors of their own age (e1). Comprehensive evidence for the efficacy of the different internet-based interventions for suicide prevention and the promotion of resilience has yet to be provided.

The risks that may arise from prescription of psychopharmaceuticals for treatment of acute and chronic suicidality in adolescents have been the subject of debate ever since the health authorities in the USA issued a warning in 2003 (e2). Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRI) have been claimed to lead to behavioral activation in adolescents with suicidal thoughts (e3, e4). Although a meta-analysis of patient data from the year 2016 found no significant difference in the incidence of suicidal thoughts or suicidal acts between antidepressants and placebo, suicidal thoughts/acts occurred around twice as often in patients given the antidepressants duloxetine, fluoxetine, paroxetine, sertraline, and venlafaxine (3.0% versus 1.1%, OR = 2.39) (e4). However, the data on children and adolescents came from only 11 selected studies (n = 2223). Moreover, suicidal thoughts/acts were not associated with higher mortality for antidepressants than for placebo. In contrast, a network analysis published in 2016 that embraced 3 times as many studies (N = 34) and 2.4 times as many patients (n = 5260) demonstrated no relevantly elevated suicide risk for children and adolescents taking antidepressants (e5). Suicidal thoughts/acts occurred in 0–13% of the randomized children and adolescents with 14 different antidepressants and in 0–14% with placebo. Only the administration of venlafaxine was associated with a significantly higher likelihood of suicidal thoughts/acts than with placebo (4.3% versus 0%)—also than with other antidepressants (duloxetine, fluoxetine, escitalopram, imipramine, paroxetine), all of which were comparable with placebo. Since some other antidepressants were associated with numerically non-significant increases in suicidal thoughts/acts, however, caution is advised, and patients should be monitored particularly closely in the early stages of treatment.

Diagnosis

The initial care of patients in a suicidal crisis or following a suicide attempt often takes place at non-psychiatric hospitals/community facilities. Apart from initiating whatever somatic measures are necessary (e.g., detoxication) the treating physician must take care that the patient performs no (more) self-harming acts (9). The patient should always be questioned about suicidality after a suicide attempt or if suicidality is suspected. Depending on the local structures, a suitable expert should be asked to assess the danger of suicide and make recommendations for the patient’s further treatment. This consultation is urgent if acute suicidality cannot be confidently excluded. The suicide risk is always assessed by means of a personal conversation in a clinical setting. Analysis of the patient’s situation with regard to stress in the family, at school, or in their social life is essential. An atmosphere of openness and acceptance is decisive for a successful conversation. Structured interviews such as the Self-Injurious Thoughts and Behavior Interview (e6)—the German version of which has been validated in a clinical sample (e7, including a link to the downloadable questionnaire)—may help to avoid overlooking any crucial aspects. However, they can never replace direct clinical evaluation. Suicidality is never triggered or reinforced by professional, anxiety-free questioning (e8). Indeed, most suicidal patients are relieved to be able to discuss this taboo, shame-/guilt-laden topic. Whenever possible, the patient’s statements should be verified or supplemented by a third person (9). Questions designed to elicit information important for clinical assessment are listed in Box 4.

BOX 4. Questions for clinical assessment of the suicide risk in a patient who has expressed suicidal thoughts.

Have there been previous suicide attempts? If so, how purposeful and dangerous were they? How high was the likelihood of discovery and rescue?

Is there a family history of completed suicide?

Are there any underlying mental illnesses? If so, what are they? Are they being adequately treated?

How concrete are the suicidal thoughts? Were preparations made? If so, what were they?

Does the patient exhibit any other self-harming behavior? If so, what? How often? When was the last time?

Has there been a suicide in the patient’s social circle? If so, when? How close/important was the person concerned?

Is there a chronic/painful underlying disease?

Does the patient lack plans for the future or display hopelessness?

Is the suicidality linked with acute trauma? If so, how long ago did the traumatic event occur?

Is the causal conflict or trigger factor still present?

Is the patient socially isolated?

Can distancing from suicide be achieved during the conversation?

Does the patient have access to fatal means of suicide (e.g., medications, guns)?

Can a credible no-harm agreement be achieved?

In exploration of suicidality the conversation always covers the patient’s history and includes the psychopathological findings (9). The differential diagnosis of NSSI has to be ruled out (9). In many patients repetitive NSSI (>5 times/year) is not an expression of suicidality, but these patients nevertheless have an elevated risk of suicide (10). In this context, Joiner speaks of the acquired ability to enact self-injury (20). Self-injury sheds its painful and anxiety-laden properties, potentially undermining a barrier to suicide. The possible presence of accompanying suicidality must therefore always be explored in cases of NSSI (9) (box 4).

Treatment

The treatment is oriented on the clinical assessment of suicidality (box 4) and may involve various interventions. New perspectives in favor of living often evolve during the course of treatment, particularly in persons who are not approaching the end of their life (e8). The central goal is therefore to gain time to deal with the person concerned in such a way that they experience alleviation of their psychic suffering and have the opportunity to rethink their perspective. If a young person shows no credible distancing from their suicidal intent, they must be admitted to a protected ward in a child and adolescent psychiatry hospital, taking care to observe the legal stipulations (ebox). If they do not cooperate voluntarily, the police and ambulance services may need to be involved (ebox).

eBox. Legal basis.

Each German federal state has laws enabling minors to be accommodated against their will in protected wards of child and adolescent psychiatry hospitals in cases of acute endangerment to self and others. Moreover, parents can (particularly in cases where there is a medium- to long-term danger that their child will harm itself or others) apply to to the family court, under the conditions of §1631 b of the German Civil Code, for the child to be treated against its will. The central criteria for expert assessors include the child’s best welfare and wellbeing, the prognosis, and the question of whether less invasive options (e.g., outpatient treatment) might not be preferable. If the treating physician considers inpatient treatment necessary but the young person’s legal guardians refuse their permission, the local youth welfare service can, in exceptional cases, take custody of the child and accommodate it in a hospital or a youth welfare facility (§42 German Social Code VIII, Child and Adolescent Welfare Act).

Decisions affecting suicidal persons always involve a feeling of personal responsibility. Although the staff of a medical institution are largely relieved of personal liability by virtue of their position in a hierarchy, they are not free of internal conflict. The findings, the measures taken, and the decision pathways must be clearly and precisely documented. If the treating physician carries out a painstaking exploration and asks the necessary questions, he/she has a margin of discretion in the evaluation of the degree of suicidality. As stated by Rüping and Lembke: “The legal authorities realize that suicide during a stay in a psychiatric hospital can never be prevented with absolute certainty” (e9).

Before discharge, the treating physician and the patient work together to develop an individual emergency plan that must be implemented if suicidal thoughts recur. Environment-related measures (e.g., family counseling, change of school, perhaps accommodation outside the family home) have the long-term goal of modifying any environmental factors and conditions that might trigger suicide (e10). It is important to treat the underlying psychiatric illness, first with psychotherapy and then, if necessary, with the appropriate medication (figure).

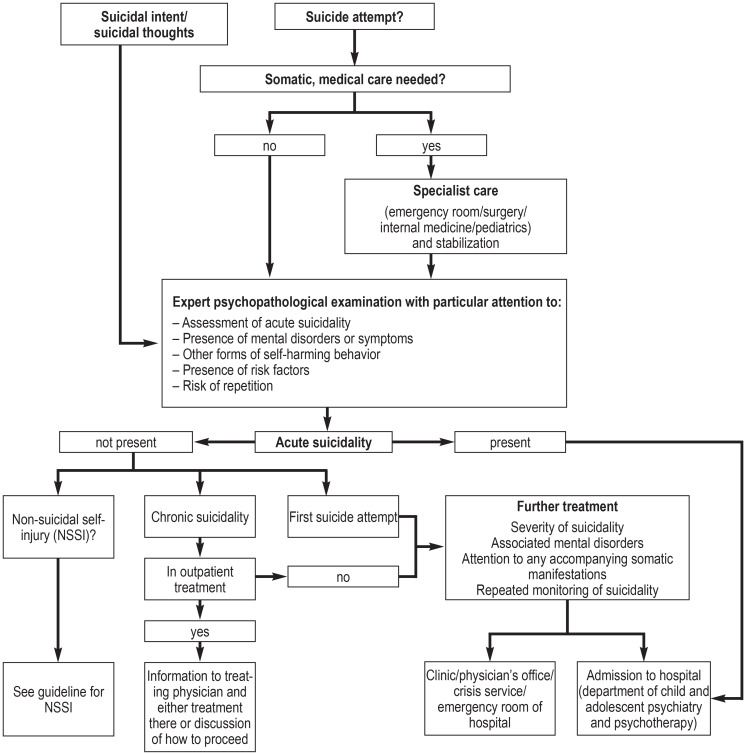

Figure.

Algorithm for treatment of suicidality in childhood and adolescence according to the guidelines of the German Society for Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Psychosomatics, and Psychotherapy (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Kinder- und Jugendpsychiatrie, Psychosomatik und Psychotherapie, DGKJP) (9)

Psychotherapeutic attitude and interventions

Inpatient child and adolescent psychiatry interventions are generally integrative, i.e., ideas and approaches from various schools of psychotherapy are used in group and/or individual sessions. Manualized treatment concepts have proved their worth particularly in the management of adolescents with repeated suicidal crises. A systematic review of 23 original articles published between 2003 and 2013 investigated the effects of psychotherapeutic interventions on suicidality in a total of 2582 adolescents (e11). Most studies found decreases in suicidal thoughts and/or suicide attempts. The effect size (ES) was particularly great when family members were included in the intervention. For example, using family-based crisis intervention in the emergency department lowered the hospitalization rate from 55% to 33% (e12), and attachment-based family therapy reduced the rate of suicidal thoughts from 87% to 52% (e13). A systematic review published in 2018 came to similar conclusions (e14). Various studies on dialectic behavioral therapy for adolescents (e15) have shown reductions in suicidal thoughts, NSSI, or suicide attempts (e16, e17). Furthermore, the positive results of an online intervention (Reframe IT) in 2016 were interesting (e18). The modules were completed on computers at school and in the home, with moderate ES for reduced suicidal thoughts (ES = 0.66) and depressive symptoms (ES = 0.60).

Apart from these specific measures, a sympathetic therapeutic stance may also be effective in dealing with suicidal patients. The appropriate approach depends on the one hand on acknowledgment of the wish to commit suicide (in view of the hopelessness perceived by the patient) and on the other hand on the conviction that the young person concerned has—under changed conditions—a life worth living in front of them (5).

Pharmacotherapy

In the acute suicidal stage, the affected person is usually highly stressed. To facilitate emotional distancing and reduction of internal tension, it may be helpful to prescribe sedatives, such as benzodiazepines (e.g., lorazepam) or low-potency first-generation antipsychotics (e.g., pipamperone, levomepromazine, chlorprothixene, melperone) (8). Secondary suicide-preventing effects have been demonstrated for lithium and clozapine, but only in adults (e19– e21).

Recent research findings indicate that a combination of psychotherapy and antidepressant medication should be considered particularly in a severe episode of depression or in severe anxiety disorder or obsessive–compulsive disorder with markedly reduced psychosocial functioning and/or high subjective distress (e22). The debate about the use of antidepressants in minors should by no means lead one not to prescribe them when they are indicated (9). If medicinal treatment is decided upon, the available data point to fluoxetine as the agent of first resort (e5). Psychoeducation and close monitoring are essential for patients taking medication (9).

Prevention

Schools have paramount importance as the place for programs to prevent suicide in childhood and adolescence (6). A successful example was provided by the school-based European Union (EU) project “Saving and Empowering Young Lives in Europe” (SEYLE) (e23), which was tested in 11 000 schools across 10 EU countries. In this project, the intervention group took part in gatekeeper training, an awareness program, and professional screening. At the 12-month follow-up, the rates of attempted suicide and suicidal thoughts were significantly lower than in the control group (minimal intervention) (e24).

Twenty-eight countries worldwide, Germany among them, have a national suicide prevention strategy (12). A 10-year review of 164 intervention studies published between 2005 and 2014 (e25) demonstrated the efficacy of a variety of measures to prevent suicides/suicide attempts. For example, installation of barriers at “hotspots” for suicide by jumping from a great height reduced the number of deaths by 86% (e26– e28). Furthermore, reduction of pack size for hepatotoxic painkillers decreased the number of suicides by 43% (e29). Randomized studies have also proved the efficacy of school discussion programs (e24, e30), which were found to reduce suicide attempts by 55% and suicidal thoughts by 50% within 12 months (e24). The interventions investigated were directed at adults and/or children and adolescents and are (except for the prescription of clozapine and lithium) transferable to minors. Pediatricians (in Germany) and primary-care physicians (in the UK) have regular contact with young people in the form of routine periodical examinations, which gives them an important role in the prevention of suicide in this age group. The following measures have proven positive effects in reducing the incidence of suicide, attempted suicide, and suicidal thoughts:

Restricted access to suicide hotspots, e.g., bridges (e26– e28)

Restricted access to, for example, weapons, painkillers, sleeping pills, and pesticides (e29)

Pharmaceutical and psychotherapeutic treatment of the underlying psychiatric disorder (e31– e33)

Specially trained primary-care physicians and pediatricians (e34– e36)

Treatment with clozapine (e37) and lithium (e38) (NB: data only for adults)

Summary

Suicidality is a significant problem in young people. Although suicidality occurs more frequently in the presence of underlying psychiatric disorders, it may also arise from acute stress reactions or adolescent crises. For this reason, persons entrusted with the care of children and adolescents should be confident in dealing with suicidality. Prevention, identification, risk assessment, and adequate treatment of suicidality in all its forms are crucial in protecting the lives of young people in suicidal crises and, ideally, making those lives worth living in the long term. In dealing with young persons who are experiencing psychosocial crises, clinicians must bear in mind the possibility of suicidal thinking and behavior.

BOX 1. Classification of the severity of suicide attempts by external circumstances (9).

-

High

Method subjectively assessed as fatal, objectively dangerous

Discovery and rescue improbable or impossible

-

Moderate

Method subjectively assessed as dangerous, but not fatal

Discovery and rescue possible

-

Low

Danger of method subjectively assessed as only slight

Discovery and rescue possible and probable

Key Messages.

In school samples, more than one third of adolescents report suicidal thoughts and 6–9% state they have attempted suicide.

Suicidal thoughts and acts in childhood and adolescence are potentially life-threatening and always require detailed evaluation, usually including psychiatric diagnosis, counseling, and, if indicated, treatment.

If the threat of suicide is judged imminent, factors specific to this age group (e.g., the lack of appreciation of danger and the tendency to act impulsively) must be taken into account.

Suicidal adolescents come into anonymous contact with relevant internet forums. This may lead to suicidality being acted out and reduced, but the result can also be maintenance and intensification of suicidality.

Suicide prevention is an important task for society; specific forms of treatment for suicidal adolescents and web-based programs have both shown early positive effects but need further evaluation.

Acknowledgments

Translated from the original German by David Roseveare

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement Prof. Correll has acted as consultant for Acadia, Alkermes, Allergan, Angelini, Axsome, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Gedeon Richter, Gerson Lehrman Group, Indivior, IntraCellular Therapies, Janssen/J&J, LB Pharma, Lundbeck, MedAvante-ProPhase, Medscape, Neurocrine, Noven, Otsuka, Pfizer, Recordati, Rovi, Sumitomo Dainippon, Sunovion, Supernus, Takeda, and Teva. He is a share option holder of LB Pharma.

Dr. Becker declares that no conflict of interest exists.

References

- 1.Statistisches Bundesamt 2017. Suizide nach Altersgruppen. www.destatis.de/DE/Themen/Gesellschaft-Umwelt/Gesundheit/Todesursachen/Tabellen/suizide.html (last accessed on 16 November 2019) [Google Scholar]

- 2.Plener PL, Libal G, Keller F, Fegert M, Muehlenkamp JJ. An international comparison of adolescent non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) and suicide attempts: Germany and the USA. Psychol Med. 2009;39:1549–1558. doi: 10.1017/S0033291708005114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Donath C, Graessel E, Baier D, Bleich S, Hillemacher T. Is parenting style a predictor of suicide attempts in a representative sample of adolescents? BMC Pediatr. 2014;14 doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-14-113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kaess M, Parzer P, Mattern M, Resch F, Bifulco A, Brunner R. Childhood Experiences of Care and Abuse (CECA) Validierung der deutschen Version von Fragebogen und korrespondierendem Interview sowie Ergebnisse einer Untersuchung von Zusammenhängen belastender Kindheitserlebnisse mit suizidalen Verhaltensweisen. Z Kinder Jugendpsychiatr Psychother. 2011;39:243–252. doi: 10.1024/1422-4917/a000115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rotthaus W. Suizidhandlungen von Kindern und Jugendlichen. Heidelberg: Carl-Auer Verlag. 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Becker K, Adam H, In-Albon T, Kaess, M, Kapusta N, Plener PL. Diagnostik und Therapie von Suizidalität im Jugendalter: Das Wichtigste in Kürze aus den aktuellen Leitlinien. Z für Kinder Jugendpsychiatr Psychother. 2017;45:485–497. doi: 10.1024/1422-4917/a000516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nock MK, Borges G, Bromet, EJ, Cha CB, Kessler RC, Lee S. Suicide and suicidal behavior. Epidemiol Rev. 2008;30:133–154. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxn002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Falkai P, Wittchen HU. American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostisches und statistisches Manual psychischer Störungen DSM-5. Göttingen: Hogrefe. 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 9.et al. Deutsche Gesellschaft für Kinder und Jugendpsychiatrie, Psychosomatik und Psychotherapie (DGKJP) Leitlinie Suizidalität im Kindes- und Jugendalter. 4. Edition. www.awmf.org/uploads/tx_szleitlinien/028-031l_S2k_Suizidalitaet_KiJu_2016-07_01.pdf (last accessed on 2 March 2020) 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Plener PL, Kaess M, Schmahl C, Pollak S, Fegert JM, Brown RC. Non-suicidal self-injury in adolescents. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2018;115:23–30. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2018.0023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hulten A, Jiang GX, Wasserman D, et al. Repetition of attempted suicide among teenagers in Europe: frequency, timing and risk factors. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2001;10:161–169. doi: 10.1007/s007870170022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.World Health Organization. Preventing suicide: a global imperative. Genf: World Health Organization. 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kokkevi A, Rotsika V, Arapaki A, Richardson C. Adolescents’ self-reported suicide attempts, self-harm thoughts and their correlates across 17 European countries. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2012;53:381–389. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2011.02457.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schmidtke A, Sell R, Löhr C. Epidemiologie von Suizidalität im Alter. Z Gerontol Geriatr. 2008;41:3–13. doi: 10.1007/s00391-008-0517-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wunderlich U, Bronisch T, Wittchen HU, Carter R. Gender differences in adolescents and young adults with suicidal behaviour. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl. 2001;104:332–339. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2001.00432.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hepp U, Stulz N, Unger-Köppel J, Ajdacic-Gross V. Methods of suicide used by children and adolescents. Eur Child Adolescent Psychiatry. 2012;21:67–73. doi: 10.1007/s00787-011-0232-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cibis A, Mergl R, Bramesfeld A, et al. Preference of lethal methods is not the only cause for higher suicide rates in males. J Affect Disord. 2012;136:9–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.08.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ringel E. Der Selbstmord. Abschluss einer krankhaften psychischen Entwicklung. Wien: Maudrich. 1953 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Glatz W. Anwalt für Drei Ethische Argumente und Problemsituationen im Umfeld von Suizidalität. Theol Gespräch Freikirchliche Beiträge Theol Suizid Suizidabsichten. 2014;38:182–202. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Joiner T. Why people die by suicide 2005. Cambridge, London: Harvard University Press. 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kostenuik M, Ratnapalan M. Approach to adolescent suicide prevention. Can Fam Physician. 2010;56:755–760. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kasper S, Kalousek M, Kapfhammer HP, Aichhorn W, Butterfield-Meissl C, Fartacek R. Suizidalität Konsensus-Statement-State of the art. CliniCum neuropsy Sonderausgabe. 2011;1 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miché M, Hofer PD, Voss C, et al. Mental disorders and the risk for the subsequent first suicide attempt: results of a community study on adolescents and young adults. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2018;27:839–848. doi: 10.1007/s00787-017-1060-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hawton K, Saunders KE, O‘Connor RC. Self-harm and suicide in adolescents. Lancet. 2012;379:2373–2382. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60322-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kirkcaldy BD, Siefen GR, Urkin J, Merrick J. Risk factors for suicidal behavior in adolescents. Minerva Pediatr. 2006;58:443–450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Takizawa R, Maughan B, Arseneault L. Adult health outcomes of childhood bullying victimization: evidence from a five-decade longitudinal British birth cohort. Am J Psychiatry. 2014;171:777–784. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.13101401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Klomek AB, Marrocco F, Kleinman M, Schonfeld IS, Gould MS. Peer victimization, depression, and suicidiality in adolescents. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2008;38:166–180. doi: 10.1521/suli.2008.38.2.166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hawton K, Rodham K, Evans E, Weatherall R. Deliberate self harm in adolescents: self report survey in schools in England. BMJ. 2002;325:1207–1211. doi: 10.1136/bmj.325.7374.1207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wunderlich U. Suizidales Verhalten im Jugendalter: Theorien, Erklärungsmodelle und Risikofaktoren. Göttingen: Hogrefe. 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Goldston A, Brunstetter DB, Daniel R, Levers S, Reboussin DM. First-time suicide attempters, repeat attempters, and previous attempters on an adolescent inpatient psychiatry unit. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1996;35:631–639. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199605000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Suk E, van Mill J, Vermeiren R, et al. Adolescent suicidal ideation: a comparison of incarcerated and school-based samples. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2009;18:377–383. doi: 10.1007/s00787-009-0740-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brunner R, Parzer P, Haffner, et al. Prevalence and psychological correlates of occasional and repetitive deliberate self-harm in adolescents. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2007;161:641–649. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.161.7.641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Feigelman W, Gorman BS. Assessing the effects of peer suicide on youth suicide. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2008;38:181–194. doi: 10.1521/suli.2008.38.2.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brent D, Greenhill L, Compton S, et al. The Treatment of Adolescent Suicide Attempters Study (TASA): predictors of suicidal events in an open treatment trial. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2009;48:987–996. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181b5dbe4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fortune S, Stewart A, Yadav V, Hawton K. Suicide in adolescents: using life charts to understand the suicidal process. J Affect Disord. 2007;100:199–210. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2006.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schmidtke A, Bille-Brahe U, DeLeo D, et al. Attempted suicide in Europe: rates, trends and sociodemographic characteristics of suicide attempters during the period 1989-1992 Results of the WHO/EURO Multicentre Study on Parasuicide. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1996;93:327–338. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1996.tb10656.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Deutsche Gesellschaft für Suizidprävention. Suizide, Suizidversuche und Suizidalität. Empfehlungen für die Berichterstattungen in den Medien 2006. www.suizidpraevention-deutschland.de/fileadmin/user_upload/Flyer/pdf-dateien/NASPRO-Medienempfehlungen-2010.pdf (last accessed on 12 May 2019) [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wikipedia. Blue Whale Challenge. https://wikipedia.org/wiki/Blue_Whale_Challenge (last accessed on 4 March 2020) [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fiedler G. Etzersdorfer E, Fiedler G, Witte M, editors. Suizidalität und neue Medien Gefahren und Möglichkeiten. Neue Medien und Suizidalität. Gefahren und Interventionsmöglichkeiten. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 40.Klicksafe. Suizidgefährdung online. www.klicksafe.de/themen/problematische-inhalte/suizidgefaehrdung-online/ (last accessed on 25 November 2019) [Google Scholar]

- E1.Caritas. Beratung für suizidgefährdete junge Menschen [U25] www.caritas.de/hilfeundberatung/onlineberatung/u25/start (last accessed on 4 March 2020) [Google Scholar]

- E2.Herpertz-Dahlmann B, Fegert JM. Zur Problematik der Gabe von selektiven Serotoninwiederaufnahmehemmern (SSRI) bei depressiven Kindern und Jugendlichen. Nervenarzt. 2004;75:908–910. doi: 10.1007/s00115-004-1792-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E3.Umetsu R, Abe J, Ueda N, et al. Association between selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor therapy and suicidality: analysis of US. Food and Drug Administration Adverse Event Reporting System Data. Biol Pharm Bull. 2015;38:1689–1699. doi: 10.1248/bpb.b15-00243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E4.Sharma T, Guski LS, Freund N, Gøtzsche PC. Suicidality and aggression during antidepressant treatment: systematic review and meta-analyses based on clinical study reports. BMJ. 2016;352 doi: 10.1136/bmj.i65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E5.Cipriani A, Zhou X, Del Giovane C, et al. Comparative efficacy and tolerability of antidepressants for major depressive disorder in children and adolescents: a network meta-analysis. Lancet. 2016;388:881–890. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30385-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E6.Nock MK, Holmberg EB, Photos VI, Michel BD. Self-injurious thoughts and behaviors interview: development, reliability, and validity in an adolescent sample. Psychol Assess. 2007;19:309–317. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.19.3.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E7.Fischer G, Ameis N, Parzer P, et al. The German version of the self-injurious thoughts and behaviors interview (SITBI-G): a tool to assess non-suicidal self-injury and suicidal behavior disorder. BMC Psychiatry Fragebogen: http://projects.iq.harvard.edu/files/nocklab/files/sitbi_shortform_german.pdf. 2014;14 doi: 10.1186/s12888-014-0265-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E8.Lewitzka U, Bauer R. Suizidalität und Sterbehilfe. Nervenarzt. 2016;87:467–473. doi: 10.1007/s00115-016-0089-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E9.Rüping U, Lembke U. Leben oder sterben lassen. Zur Suizidpaktentscheidung des Oberlandesgerichts Braunschweig. Psychotherapeutenjournal. 2008;2:369–363. [Google Scholar]

- E10.Lempp T. BASICS Kinder-und Jugendpsychiatrie. München: Urban & Fischer/Elsevier. 2016 [Google Scholar]

- E11.Kapusta ND, Fegert JM, Haring C, Plener PL. Psychotherapeutische Interventionen bei suizidalen Jugendlichen. Psychotherapeut. 2014;5:16–23. [Google Scholar]

- E12.Wharff EA, Ginnis KM, Ross AM. Family-based crisis intervention with suicidal adolescents in the emergency room: a pilot study. Soc Work. 2012;57:133–143. doi: 10.1093/sw/sws017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E13.Diamond GS, Wintersteen MB, Brown GK, et al. Attachment-based family therapy for adolescents with suicidal ideation: arandomized controlled trial. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010;49:122–131. doi: 10.1097/00004583-201002000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E14.Iyengar U, Snowden N, Asarnow JR, Moran P, Tramah T, Ougrin D. A further look at therapeutic interventions for suicide attempts and self-harm in adolescents: an updated systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Front Psychiatry. 2018;9 doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E15.Fleischhaker C, Munz M, Böhme R, Sixt B, Schulz E. Dialektisch-Behaviorale Therapie für Adoleszente (DBT-A) - Eine Pilotstudie zur Therapie von Suizidalität, Parasuizidalität und selbstverletzenden Verhaltensweisen bei Patientinnen mit Symptomen einer Borderlinestörung. Z Kinder Jugendpsychiatr Psychother. 2006;34:15–25. doi: 10.1024/1422-4917.34.1.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E16.Fleischhaker C, Böhme R, Sixt B, Brück C, Schneider C, Schulz E. Dialectical behavioral therapy for adolescents (DBT-A): a clinical trial for patients with suicidal and self-injurious behavior and borderline symptoms with a one-year follow-up. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. 2011;28 doi: 10.1186/1753-2000-5-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E17.Mehlum, L, Tørmoen AJ, Ramberg, et al. Dialectical behavior therapy for adolescents with repeated suicidal and self-harming behavior: a randomized trial. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2014;53:1082–1091. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2014.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E18.Robinson J, Hetrick S, Cox G, et al. Can an internet-based intervention reduce suicidal ideation, depression and hopelessness among secondary school students: results from a pilot study. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2016;10:28–35. doi: 10.1111/eip.12137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E19.Cipriani A, Hawton, K, Stockton S, Geddes JR. Lithium in the prevention of suicide in mood disorders: updated systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2013;346 doi: 10.1136/bmj.f3646. f3646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E20.Ahrens B, Müller-Oerlinghausen B. Does lithium exert an independent antisuicidal effect? Pharmacopsychiatry. 2001;34:132–136. doi: 10.1055/s-2001-15878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E21.Meltzer HY, Alphs L, Green AI, et al. International Suicide Prevention Trial Study Group Clozapine treatment for suicidality in schizophrenia: International Suicide Prevention Trial (InterSePT) Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60:82–91. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.1.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E22.Correll CU, Kratochvil CJ, March J. Developments in pediatric psychopharmacology: focus on stimulants, antidepressants and antipsychotics. J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72:655–670. doi: 10.4088/JCP.11r07064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E23.Wasserman D, Carli V, Wasserman C, et al. Saving and empowering young lives in Europe (SEYLE): a randomized controlled trial. BMC Public Health. 2010;10 doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E24.Wasserman D, Hoven CW, Wasserman C, et al. School-based suicide prevention programmes: the SEYLE cluster-randomised, controlled trial. Lancet. 2015;385:1536–1544. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61213-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E25.Zalsman G, Hawton K, Wasserman D, et al. Suicide prevention strategies revisited: 10-year systematic review. The Lancet Psychiatry. 2016;3:646–659. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(16)30030-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E26.Pirkis J, Spittal MJ, Cox G, Robinson J, Cheung YT, Studdert D. The effectiveness of structural interventions at suicide hotspots: a meta-analysis. Int J Epidemiol. 2013;42:541–548. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyt021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E27.Perron S, Burrows S, Fournier M, Perron PA, Ouellet F. Installation of a bridge barrier as a suicide prevention strategy in Montreal, Quebec, Canada. Am J Public Health. 2013;103:1235–1239. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E28.Law CK, Sveticic J, De Leo D. Restricting access to a suicide hotspot does not shift the problem to another location. An experiment of two river bridges in Brisbane, Australia. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2014;38:134–138. doi: 10.1111/1753-6405.12157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E29.Hawton K, Bergen H, Simkin S, et al. Long term effect of reduced pack sizes of paracetamol on poisoning deaths and liver transplant activity in England and Wales: interrupted time series analyses. BMJ. 2013;346 doi: 10.1136/bmj.f403. f403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E30.Aseltine Jr RH, James A, Schilling EA, Glanovsky J. Evaluating the SOS suicide prevention program: a replication and extension. BMC Public Health. 2007;7 doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-7-161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E31.March JS, Silva S, Petrycki S, et al. The treatment for adolescents with depression study (TADS): long-term effectiveness and safety outcomes. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64:1132–1143. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.10.1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E32.Tarrier N, Taylor K, Gooding P. Cognitive-behavioral interventions to reduce suicide behavior: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Behav Modif. 2008;32:77–108. doi: 10.1177/0145445507304728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E33.Robinson J, Hetrick SE, Martin C. Preventing suicide in young people: systematic review. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2011;45:3–26. doi: 10.3109/00048674.2010.511147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E34.Henriksson S, Isacsson G. Increased antidepressant use and fewer suicides in Jamtland county, Sweden, after a primary care educational programme on the treatment of depression. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2006;114:159–167. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2006.00822.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E35.Szanto K, Kalmar S, Hendin H, Rihmer Z, Mann JJ. A suicide prevention program in a region with a very high suicide rate. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64:914–920. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.8.914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E36.Roskar S, Podlesek A, Zorko M, et al. Effects of training program on recognition and management of depression and suicide risk evaluation for Slovenian primary-care physicians: follow-up study. Croat Med J. 2010;51:237–242. doi: 10.3325/cmj.2010.51.237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E37.Asenjo Lobos C, Komossa K, Rummel-Kluge C, et al. Clozapine versus other atypical antipsychotics for schizophrenia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;11 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006633.pub2. CD006633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E38.Lauterbach E, Felber W, Muller-Oerlinghausen B, et al. Adjunctive lithium treatment in the prevention of suicidal behaviour in depressive disorders: a randomised, placebo-controlled, 1-year trial. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2008;118:469–479. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2008.01266.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]