Abstract

Background

We reported a relatively high rate of MetS in rural Northeast residents in 2012–2013. Many strategies like health knowledge propagation and lifestyle modification have been taken to help rural residents decrease metabolic disorders. Hence, we held the present follow-up study in order to figure the changes of metabolic parameters and the possible reasons together with the evaluation of MetS incidence and associated risk factors.

Methods

A population-based sample of 8147 rural Northeast Chinese residents aged ≥ 35 years at baseline were followed up from 2012–2013 to 2015–2017. MetS was diagnosed following the unify criteria in 2009 using the Asian specific criteria.

Results

Among residents with MetS at baseline, value of systolic, diastolic blood pressure, total cholesterol, HDL-C decreased while waist circumference increased in both genders in follow-up. Discrepancy of trend in body mass index, LDL-C and estimated GFR existed between male and female. Besides, triglyceride increased, and fast glucose decreased in female only. The alterations of dietary pattern might be accountable for those changes. Among residents without MetS at baseline, the cumulative incidence of newly diagnosed MetS was 24.0% (25.8% for male; 22.3% for female). As the number of metabolic disorders increased at baseline, the incidence of MetS also increased (zero metabolic disorder: 8.3%; one metabolic disorder: 17.1%; two metabolic disorders: 35.4%). In male residents, bad living habits like smoking and drinking were associated with increasing risk of Mets while in female, higher risk of MetS was more likely relevant to dietary pattern.

Conclusion

Metabolic parameters changes during the past years and seem to be associated with alteration of diet pattern. Incidence of MetS still high among rural Northeast Chinese. The risk factors of higher incidence of MetS show gender discrepancy which make the prophylaxis and control of MetS more effective and directive in rural residents.

Keywords: Incidence, MetS, Metabolic disorders, Gender, Discrepancy, Dietary changes

Background

MetS is the cluster of metabolic disorders that include elevated blood pressure, abdominal obesity, insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, and is strongly associated with increased risk of many diseases like twofold for cardiovascular disease and 5- fold or more for type 2 diabetes [1, 2]. Besides, in recent year, growing evidence claimed that MetS was relevant to many other kinds of diseases, like breast cancer, hypothyroidism and cerebral microbleeds [3–5]. MetS has already become a huge potential risk factors for public health. Out previous study reported the high prevalence (39.0%) of MetS among rural Northeast Chinese (45.6% for female; 31.4% for male). There are growing propagation about health lifestyle modification and investment of medical source on public health in China. However, the incidence of MetS still increased from 8 to 10.6% in urban areas and 4.9 to 5.3% in rural areas [6]. Previous study reported that during 1988–2010, there is a significantly increase of waist circumference (WC) in general population in USA [7]. While other study in Ahvaz claimed that lipid profile like HDL, triglycerides and Cholesterol decreased from 2009 to 2014 among general subjects over 20 years old [8]. However, there is lack of study focus on the metabolic changes among previous diagnosed MetS. Whether their metabolic parameters improved or worse during the past years. Hence, one aim of the present study is to estimate the changes of metabolic parameters between 2012–2013 and 2015–2017. Through this investigation we can figure out whether the strategies like health knowledge propagation and lifestyle modification works or not. Second, to estimate the cumulative incidence of MetS between 2012–2013 and 2015–2017 and found the possible risk factors for better control.

Materials and methods

Study population

The Northeast China Rural Cardiovascular Health Study (NCRCHS) is a community-based prospective cohort study carried out in rural areas of Northeast China. The design and inclusion criteria of the study has been described previously [9, 10]. In brief, a total of 11,956 participants aged ≥ 35 years were recruited from Dawa, Zhangwu and Liaoyang counties in Liaoning province between 2012 and 2013, using a multi-stage, randomly stratified cluster-sampling scheme. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of China Medical University (Shenyang, China AF-SDP-07-1, 0-01). Detailed information was collected at baseline for each participant. In 2015 and 2017, participants were invited to attend a follow-up study. Of the 11,956 subjects, 1256 participants were not included due to missing contact information and 10,349 participants (86.6%) completed at least one follow-up visit. The median follow-up was 4.66 years. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of China Medical University (Shenyang, China). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. In the current analyses, we excluded participants with a history of stroke (n = 387), coronary heart disease (CHD, n = 520) or heart failure at baseline. Complete information on co-variables from the baseline visit was required for inclusion in the current analyses. Finally, data were available for 8147 participants.

Study variables

At baseline, detailed information on demographic characteristics, dietary and lifestyle factors and medical history were obtained by interview with a standardized questionnaire. Smoking and drinking status were defined as current use. Dietary pattern included were assessed by residents recall the foods that they eat. The questionnaire included questions regarding the average consumption of different food items per week. Vegetable consumption was assessed on the following scale: rarely, < 1000 g, 1000–1500 g, 1500–2000 g, > 2000 g; Meat consumption, including red meat, fish and poultry was assessed on the following scale: rarely, < 250 g, 250–500 g, > 500 g; Bean and bean product consumption was assessed on the following scale: rarely, 2–3times, ≥ 4 times; Greasy food consumption was assessed on the following scale: rarely, 2–3 times, ≥ 4 times; Tea consumption: No, occasionally, 1–2 times, ≥ 3 times; Physical activity contained occupational and leisure-time physical activity. We have detailed descripted it previously [9]. It is divided into three classes, low, moderate and heavy. History of stroke, CHD and heart failure at baseline was defined as self-reported and confirmed by medical records. Weight and height were measured with participants in light weight clothing and without shoes. Waist circumference was measured at the umbilicus using a non-elastic tape. Body mass index (BMI) was computed as weight in kilograms divided by the square of height in meters. Obesity was defined as BMI ≥ 28 kg/m2 [11]. Blood pressure was assessed three times with participants seated after at least 5 min of rest using a standardized automatic electronic sphygmomanometer (HEM-907; Omron, Tokyo, Japan). Hypertension was defined as systolic blood pressure (SBP) ≥ 140 mm Hg and/or diastolic blood pressure (DBP) ≥ 90 mm Hg, and/or use of antihypertensive medications [12]. Fasting blood samples were collected in the morning from participants who had fasted at least 12 h. Fasting plasma glucose (FPG), total cholesterol (TC), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), triglyceride (TG), serum creatinine and other routine blood biochemical indexes were analyzed enzymatically. Estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was calculated using the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) equation [13]. MetS was diagnosed follow the unify criteria from the meeting between several major organizations in 2009 [14]: The presence of any 3 of 5 risk factors constitutes a diagnosis of metabolic syndrome. 1. Elevated waist circumference (population- and country-specific definitions): ≥ 90 cm for men; ≥ 80 cm for women (Asians; Japanese; South and Central Americans); 2. Elevated triglycerides (drug treatment for elevated triglycerides is an alternate indicator): ≥ 150 mg/dL (1.7 mmol/L); 3. Reduced HDL-C (drug treatment for reduced HDL-C is an alternate indicator): < 40 mg/dL (1.0 mmol/L) in men; < 50 mg/dL (1.3 mmol/L) in women; 4. Elevated blood pressure (antihypertensive drug treatment in a patient with a history of hypertension is an alternate indicator): Systolic ≥ 130 and/or diastolic ≥ 85 mm Hg; 5. Elevated fasting glucose (drug treatment of elevated glucose is an alternate indicator): ≥ 100 mg/dL;

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated for all the variables, including continuous variables (reported as mean values and standard deviations) and categorical variables (reported as numbers and percentages). Differences among categories were evaluated using t-test, ANOVA, non-parameter test or the χ2-test as appropriate. We used logistic regression analyses to estimate odds ratio (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the possible risk factors of MetS after adjusting for possible confounders. All the statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 17.0 software, and P values less than 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Changes of biochemical parameters from baseline to follow-up in different gender among residents with MetS in baseline

At baseline, 3167 residents were diagnosed MetS. We intend to estimate the changes of their metabolic parameter like SBP, BDP, WC and biochemical indexes in the past years. Data was shown in Table 1. At baseline, Male residents with Mets had higher value of SBP, DBP, BMI, WC, TG, FPG, UA and eGFR than female residents. On the contrary, female had relatively higher value of LDL-C, and HDL-C when compared with male. Similarly, in the follow-up, comparison of this parameters between female and male showed the same results as in the baseline except that there is no significant difference of eGFR between female and male in follow-up (P = 0.141). When compared data of baseline to follow-up, we can see there was apparent decrease of SBP, DBP and HDL in both gender. And discrepancies were observed in BMI, LDL-C and eGFR in different gender. BMI increased in male but decreased in female while others decreased in male and increased in female (LDL-C and eGFR). WC increased in follow-up compared with baseline in both genders. TG significantly increased while FPG significantly decreased in follow-up in comparison with baseline in female only.

Table 1.

Metabolic parameters changes from 2012–2013 to 2015–2017 in MetS residents in baseline

| Male | Female | Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Follow-up | Baseline | Follow-up | Baseline | Follow-up | |

| SBP (mmHg) | 152.72 ± 21.44 | 147.67 ± 21.44* | 149.86 ± 23.31 | 143.41 ± 23.06* | 151.11 ± 22.71 | 145.14 ± 22.55* |

| DBP (mmHg) | 89.16 ± 11.49 | 88.04 ± 12.28* | 84.51 ± 11.20 | 83.35 ± 12.09* | 86.26 ± 11.53 | 85.11 ± 12.37* |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 27.24 ± 3.23 | 28.15 ± 3.74* | 26.68 ± 3.47 | 25.78 ± 3.75* | 26.89 ± 3.39 | 26.67 ± 3.92* |

| WC (cm) | 91.58 ± 8.41 | 93.42 ± 8.59* | 86.71 ± 8.31 | 89.44 ± 8.88* | 88.54 ± 8.67 | 90.94 ± 8.98* |

| TG (mmol/L) | 2.63 ± 2.32 | 2.59 ± 2.29 | 2.15 ± 1.61 | 2.28 ± 1.03# | 2.63 ± 2.31 | 2.40 ± 2.02 |

| LDL-C(mmol/L) | 3.11 ± 0.88 | 3.06 ± 0.92# | 3.22 ± 0.91 | 3.26 ± 0.93# | 3.18 ± 0.90 | 3.18 ± 0.93 |

| HDL-C (mmol/L) | 1.20 ± 0.33 | 1.12 ± 0.34* | 1.27 ± 0.29 | 1.21 ± 0.33* | 1.25 ± 0.31 | 1.17 ± 0.34* |

| FPG (mmol/L) | 6.61 ± 2.22 | 6.35 ± 2.18 | 6.43 ± 1.98 | 6.27 ± 2.08* | 6.50 ± 2.07 | 6.35 ± 2.18* |

| UA (mmol/L) | 359.99 ± 84.02 | 357.29 ± 82.60 | 273.52 ± 70.49 | 274.19 ± 66.15 | 305.94 ± 86.63 | 305.35 ± 83.13 |

| eGFR (mi/min/1.73 m2) | 92.35 ± 14.13 | 90.63 ± 14.61* | 89.35 ± 16.47 | 91.45 ± 14.52* | 90.47 ± 15.71 | 91.15 ± 14.56# |

| Current smoking (%) | 52.4% | 50.5% | 16.0% | 15.3% | 29.6% | 28.5% |

| Current drinking (%) | 45.0% | 45.3% | 2.7% | 3.6%# | 18.5% | 19.2% |

SBP systolic blood pressure, DBP diastolic blood pressure, TC total cholesterol, TG triglyceride, LDL-C low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, HDL-C high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, FPG fasting plasma glucose, UA uUric acid

* Means P < 0.001 compared to baseline; # means P < 0.05 compared to baseline

Dietary pattern changes from baseline to follow-up among residents with MetS in baseline

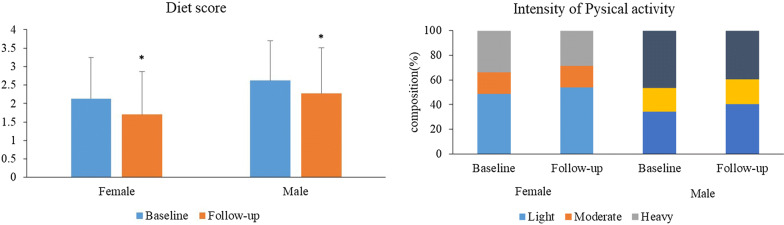

Figure 1 shown the changes of dietary pattern and intensity of physical activity from baseline to follow-up. The mean value of diet score in baseline was 2.13 ± 1.11 in female and 2.62 ± 1.08 in male. In both gender, the diet score significantly decreased in follow-up (1.70 ± 1.16 for female; 2.27 ± 1.24 for male). The higher value of diet score suggested a higher consumption of meat and lower consumption of vegetable. As for physical activity, we can see there is a significantly increase of light and decrease of heavy intensity of physical activity in the follow-up in both genders.

Fig. 1.

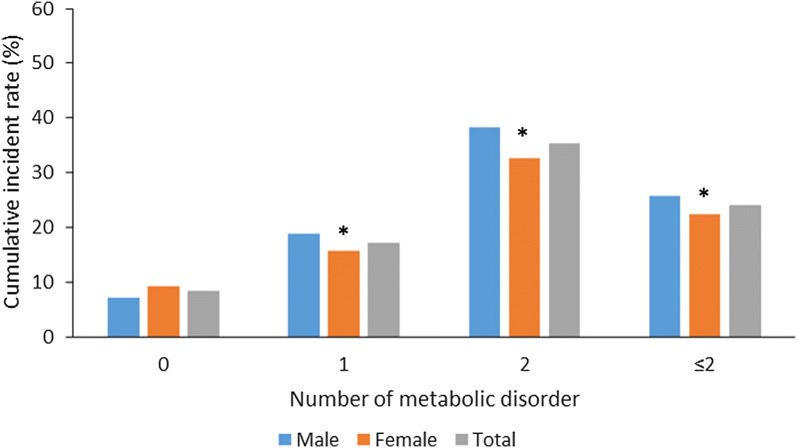

Gender difference of cumulative incidence of MetS during the 4.66 years median follow-up in different numbers of metabolic disorders in baseline

Cumulative incidence of MetS among residents without Mets in baseline

In present study, 4980 participants in baseline did not diagnosed of Mets. After the median 4.6 years follow-up, 1194 participants were newly diagnosed MetS (total: 24.0%; female: 22.3%; male: 25.8%). Besides, in Fig. 2. There is an increasing trend of MetS from participants without metabolic disorders to those with 2 metabolic disorders in baseline. Besides, female had significantly higher incidence of MetS than male in all the groups except for participant without metabolic disorder at baseline.

Fig. 2.

Changes of diet pattern and intensity of physical activity from baseline to follow-up

Baseline characteristics of newly diagnosed MetS at follow-up

In Table 2. We can see newly diagnosed MetS were more likely to be women, older aged. MetS had higher rate of both primary school or below and high school or above compared with Non- MetS. Besides, MetS residents were less like to have severe physical activity. As for metabolic disorders, MetS had significantly higher baseline value of SBP, DBP, BMI, WC, TC, TG, LDL-C and FPG whereas significantly lower HDL-C. However, there is no difference existed among current smoking and drinking between MetS and Non-MetS.

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of rural Northeast Chinese residents by MetS status at follow-up overall and by non-MetS and MetS among residents without MetS at baseline

| Variables | Total (n = 4980) | Non-MetS (n = 3786) | MetS (n = 1194) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Man | 2586 (51.9) | 2010 (53.1) | 576 (48.2) | 0.002 |

| Age (years) | 52.65 ± 10.21 | 52.20 ± 10.28 | 54.08 ± 9.89 | < 0.001 |

| Ethnicity | 0.216 | |||

| Han | 316 (6.3) | 234 (6.2) | 82 (6.9) | |

| Othersa | 4664 (93.7) | 3552 (93.8) | 1112 (93.1) | |

| Education status | 0.002 | |||

| Primary school or below | 2331 (46.8) | 1720 (45.4) | 611 (51.2) | |

| Middle school | 2167 (43.5) | 1689 (44.6) | 478 (40.0) | |

| High school or above | 482 (9.7) | 377 (10.0) | 105 (21.8) | |

| Physical activity | 0.002 | |||

| Light | 1537 (31.2) | 1123 (29.9) | 414 (35.1) | |

| Moderate | 918 (18.6) | 721 (19.2) | 197 (16.7) | |

| Severe | 2479 (50.2) | 1910 (50.9) | 569 (48.2) | |

| Annual income (CNY/year) | 0.055 | |||

| ≤ 5000 | 532(10.7) | 399 (10.5) | 133 (11.1) | |

| 5000–20,000 | 2801(56.3) | 2101 (55.5) | 700 (58.7) | |

| > 20,000 | 1644(33.0) | 1284 (33.9) | 360 (30.2) | |

| Current smoking status (Yes) | 1928(38.7) | 1486 (39.2) | 442 (37.0) | 0.089 |

| Current drinking status (No) | 1278(25.7) | 970 (25.6) | 308 (25.8) | 0.466 |

| Marriage (Yes) | 4922(98.8) | 3747(99.0) | 1175 (98.4) | 0.081 |

| Sleep duration (h/day) | 7.27 ± 1.65 | 7.27 ± 1.64 | 7.29 ± 1.69 | 0.746 |

| SBP (mmHg) | 136.55 ± 21.85 | 134.58 ± 21.05 | 142.79 ± 23.16 | < 0.001 |

| DBP (mmHg) | 79.73 ± 11.00 | 78.92 ± 10.69 | 82.33 ± 11.58 | < 0.001 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 23.59 ± 3.21 | 23.16 ± 3.15 | 24.93 ± 3.03 | < 0.001 |

| WC (cm) | 78.39 ± 8.38 | 77.28 ± 8.06 | 81.94 ± 8.40 | < 0.001 |

| TC (mmol/L) | 5.10 ± 0.99 | 5.04 ± 0.96 | 5.31 ± 1.05 | < 0.001 |

| TG (mmol/L) | 1.14 ± 0.75 | 1.07 ± 0.55 | 1.36 ± 1.14 | < 0.001 |

| LDL-C (mmol/L) | 2.83 ± 0.76 | 2.75 ± 0.73 | 3.06 ± 0.80 | < 0.001 |

| HDL-C (mmol/L) | 1.52 ± 0.39 | 1.55 ± 0.39 | 1.46 ± 0.37 | < 0.001 |

| FPG (mmol/L) | 5.50 ± 1.06 | 5.47 ± 1.03 | 5.60 ± 1.14 | < 0.001 |

Data are expressed as the mean ± SD or as n (%)

BMI body mass index, WC waist circumference, CNY China Yuan (1CNY = 0.161 USD), SBP systolic blood pressure, DBP diastolic blood pressure, TG triglyceride, LDL-C low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, HDL-C high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, FPG fasting plasma glucose

aIncluding some ethnic minorities in China, such as Mongol and Manchu

Cumulative incidence rate of MetS by different status markers and the possible risk factors associated with higher incidence of MetS

Table 3 showed that there is discrepancy of incidence of MetS among female and male. In female, there is a significantly increasing incidence of MetS as the age increased. Female residents who have more than 1 children also had significantly high incidence of MetS compared to those with one or less child. With the education level increased from primary school or below to high school or above, the incidence of MetS also decreased in female. In male, residents without marriage have relatively higher incidence of MetS than those married. Besides, there is contrary result existed in current smoking status, compared to non-current smoker, male current smoker has low rate of MetS while female current smoker had higher incidence rate. As for drinking status, current drinker had significantly higher incidence of MetS than non-current drinkers in male. In male, the single associated risk factors of higher incidence of MetS was current drinking while married status and current smoking were associated with lower incidence. However, in female, increasing age, ≥ 4 times/w bean and bean product consumption and tea intake were related with higher incidence of MetS.

Table 3.

Cumulative incidence rate of MetS by levels of different status markers and multiple logistic regression analysis of MetS incidence and the associated factors in the rural population of Liaoning Province, China

| Male | Female | Total | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Cumulative incidence (%) | OR (95% CI) | N | Cumulative incidence (%) | OR (95% CI) | N | Cumulative incidence (%) | OR (95% CI) | |

| Age | |||||||||

| 35–44 | 124 | 21.4 | 1.00 (reference) | 124 | 16.2 | 1.00 (reference) | 248 | 18.5 | 1.00 (reference) |

| 45–54 | 166 | 21.3 | 1.02 (0.78,1.43) | 222 | 26.5 | 1.78 (1.37,2.31) | 388 | 24.0 | 1.40 (1.16,1.69) |

| 55–64 | 197 | 23.9 | 1.13 (0.85,1.50) | 199 | 33.6 | 2.41 (1.78,3.25) | 396 | 28.0 | 1.69 (1.37,2.07) |

| ≥ 65 | 89 | 22.1 | 1.02 (0.70,1.48) | 73 | 36.7 | 2.61 (1.73,3.95) | 162 | 26.9 | 1.57 (1.19,2.07) |

| Number of child | |||||||||

| ≤ 1 | 235 | 21.8 | 1.00 (reference) | 257 | 23.4 | 1.00 (reference) | 492 | 22.6 | 1.00 (reference) |

| > 1 | 341 | 22.6 | 1.04 (0.85,1.29) | 361 | 27.8 | 0.97 (0.79,1.19) | 702 | 25.0 | 1.00 (0.87,1.16) |

| Ethnicity | |||||||||

| Hank | 538 | 22.2 | 1.00 (reference) | 574 | 25.6 | 1.00 (reference) | 1112 | 23.8 | 1.00 (reference) |

| Othersa | 38 | 23.6 | 1.04 (0.71,1.54) | 44 | 28.4 | 1.11 (0.76,1.62) | 82 | 25.9 | 1.19 (0.84,1.44) |

| Education status | |||||||||

| Primary school or below | 245 | 22.5 | 1.00 (reference) | 366 | 29.5 | 1.00 (reference) | 611 | 26.2 | 1.00 (reference) |

| Middle school | 273 | 22.1 | 0.99 (0.80,1.22) | 205 | 22.0 | 0.91 (0.73,1.13) | 478 | 22.1 | 0.93 (0.80,1.08) |

| High school or above | 58 | 22.4 | 1.04 (0.73,1.47) | 47 | 21.1 | 0.82 (0.56,1.19) | 105 | 21.8 | 0.89 (0.69,1.14) |

| Physical activity | |||||||||

| Light | 150 | 22.8 | 1.00 (reference) | 264 | 30.0 | 1.00 (reference) | 414 | 26.9 | 1.00 (reference) |

| Moderate | 90 | 19.7 | 0.88 (0.64,1.19) | 107 | 23.3 | 0.79 (0.60,1.04) | 197 | 21.5 | 0.81 (0.66,0.99) |

| Severe | 327 | 22.6 | 1.06 (0.82,1.35) | 242 | 23.4 | 0.83 (0.67,1.04) | 569 | 23.0 | 0.92 (0.78,1.08) |

| Annual income (CNY/year) | |||||||||

| ≤ 5000 | 72 | 22.6 | 1.00 (reference) | 61 | 28.6 | 1.00 (reference) | 133 | 25.0 | 1.00 (reference) |

| 5000–20,000 | 336 | 23.0 | 1.06 (0.78,1.43) | 364 | 27.1 | 1.10 (0.78,1.55) | 700 | 25.0 | 1.08 (0.86,1.35) |

| > 20,000 | 168 | 20.8 | 0.94 (0.67,1.32) | 192 | 22.9 | 1.01 (0.70,1.46) | 360 | 21.9 | 0.97 (0.76,1.24) |

| Sleep duration (h/day) | |||||||||

| ≤ 7 | 260 | 21.8 | 1.00 (reference) | 316 | 25.0 | 1.00 (reference) | 576 | 23.5 | 1.00 (reference) |

| 7–8 | 171 | 22.0 | 1.02 (0.81,1.26) | 190 | 27.6 | 1.34 (1.07,1.67) | 361 | 24.6 | 1.14 (0.98,1.33) |

| 8–9 | 91 | 22.9 | 1.05 (0.79,1.39) | 70 | 25.1 | 1.08 (0.79,1.47) | 161 | 23.8 | 1.06 (0.86,1.30) |

| > 9 | 53 | 24.5 | 1.22 (0.86,1.73) | 41 | 25.6 | 1.16 (0.78,1.72) | 94 | 25.0 | 1.16 (0.89,1.50) |

| Marriage | |||||||||

| No | 19 | 37.3 | 1.00(reference) | 0 | 0 | 1.00 (reference) | 19 | 32.8 | 1.00(reference) |

| Yesb | 557 | 22.0 | 0.46(0.25,0.85) | 618 | 25.9 | - | 1175 | 23.9 | 0.57(0.32,1.03) |

| Current smoking status | |||||||||

| No | 252 | 24.0 | 1.00 (reference) | 500 | 25.0 | 1.00 (reference) | 752 | 24.6 | 1.00 (reference) |

| Yes | 324 | 21.1 | 0.81 (0.67,0.99) | 118 | 30.1 | 1.09 (0.84,1.41) | 442 | 22.9 | 0.94 (0.81,1.11) |

| Current drinking status | |||||||||

| No | 287 | 20.8 | 1.00 (reference) | 599 | 25.8 | 1.00 (reference) | 886 | 23.9 | 1.00 (reference) |

| Yes | 289 | 23.9 | 1.23 (1.01,1.50) | 19 | 26.8 | 0.80 (0.46,1.42) | 308 | 24.1 | 1.17 (0.98,1.41) |

| Beans or Bean product | |||||||||

| Rarely | 173 | 20.3 | 1.00 (reference) | 254 | 25.1 | 1.00 (reference) | 427 | 22.9 | 1.00 (reference) |

| 2–3 times | 324 | 23.3 | 1.18 (0.95,1.46) | 286 | 25.2 | 1.02 (0.84,1.25) | 610 | 24.1 | 1.10 (0.95,1.28) |

| ≥ 4 times | 75 | 22.7 | 1.15 (0.84,1.58) | 76 | 31.7 | 1.43 (1.04,1.96) | 151 | 26.5 | 1.26 (1.01,1.57) |

| Tea intake (Frequency/day) | |||||||||

| No | 173 | 20.3 | 1.00 (reference) | 422 | 24.4 | 1.00 (reference) | 685 | 22.8 | 1.00 (reference) |

| Rarely | 324 | 23.3 | 1.22 (0.96,1.53) | 115 | 28.5 | 1.37 (1.07,1.77) | 269 | 26.0 | 1.29 (1.09,1.53) |

| 1–2 times | 75 | 22.7 | 1.12 (0.87,1.43) | 75 | 31.6 | 1.43 (1.05,1.95) | 208 | 25.8 | 1.24 (1.02,1.50) |

| 3–4 times | 572 | 22.2 | 1.09 (0.67,1.77) | 6 | 26.1 | 1.29 (0.49,3.38) | 31 | 23.3 | 1.09 (0.71,1.68) |

Adjusted for Cardiovascular diseases (angina, myocardial infarction, arrhythmia, and heart failure), cerebrovascular diseases (cerebral hemorrhage, cerebral infarction, subarachnoid hemorrhage, Transient Ischemic Attack) and chronic kidney diseases (nephritis, acute/chronic renal failure)

OR odds ratio, 95% CI 95% confidence interval

Italics means P < 0.05; CNY, China Yuan (1CNY = 0.161 USD)

aIncluding some ethnic minorities in China, such as Mongol and Manchu

bIncluding widowed, divorced/separated and unmarried

Discussion

In the present study, we reported the changes of metabolic parameters. In male with MetS at baseline, BMI and WC significantly increased in the follow-up whereas HDL, blood pressure and LDL decreased. While in female with MetS at baseline, WC, TG and LDL increased but HDL, blood pressure, FPG and BMI all decreased in follow-up. Diet score significantly lower in both gender at follow-up while residents had higher light intensity than they had in baseline. The cumulative incidence of MetS was higher in female than in male. Besides, with the increase metabolic disorders in baseline, the incidence of MetS also increased. Gender discrepancy existed among the risk factors of developing MetS. In male, current drinking was risk factors while current smoking and married status were protective factors. In female, bean and bean product consumption and tea consumption were associated with higher risk of developing MetS.

NHNES data found that average BMI increased by 0.37% per year in both male and female while WC increase 0.37 and 0.27% per year in female [7]. While in our study, among previous diagnosed MetS residents, WC increased during follow-up in both genders whereas BMI increased in male but decreased in female. This is might be due to the increasing age. Previous studies concluded that rate of abdominal obesity increased with age [15, 16]. Also it might be relevant to the decrease rate high and moderate physical activity intensity. MetS is associated with physical inactivity and unhealthy diet [19]. From data of our study, diet score decreased significantly during follow-up. This might be helpful to control hypertension, dyslipidemia and diabetes. Blood pressure, both systolic and diastolic blood pressure significantly decreased in the follow-up in both gender. As diet pattern index, diet score inferred the composition of diet. The higher score means more meat and less vegetable which are more similar to Western diet while lower score are more likely Mediterranean diet. Courtney R Davis and colleagues confirmed that Mediterranean diet help to lower blood pressure and improved endothelial function [17]. Besides, more vegetable and less meat diet showed great improvement of high glucose level and HbA1c level [18]. Adherence to a healthy diet has been proved to be associated with lower risk of MetS in both developing and developed countries [19, 20]. On interesting thing in the follow-up is that dyslipidemia was even worse in female residents with previously diagnosed MetS. The value of TG and LDL-C increased while HDL-C decrease significantly in follow-up. This might be due to the larger rate of postmenopausal female in the follow-up. A cumulative evidence inferred that menopause status had close relationship with dyslipidemia in female [21]. Increased prevalence of dyslipidemia was associated not only with the post-menopausal stage but also late menopausal transition period [22]. In the present study, 177 female residents transited to post-menopause during the past years and 1544 in total were post-menopause. Therefore, unlike in male, lipid parameters increased in female.

Hongge Sun and colleagues reported an 18.55% cumulative incidence of MetS during the 7 years of follow-up in Chinese residents [23]. Adriano M Pimenta also claimed 6.0% cumulative incidence of MetS during the 8.3 years of follow-up in Spanish [24]. As for our present study, the cumulative incidence of MetS was 24.0% during the 4.3 year of follow-up which was significantly higher than many previous studies. However, Yazd Health Heart Project reported a relatively higher incidence with 56.1% after 10 year follow-up and concluded that increased risk of MetS was in those did not usually eat salad and did not try to control their body [25]. While in our study, there is discrepancy of risk factors among female and male residents. In male residents without MetS at baseline, the only risk factor that has statistical difference is current drinking status. One recent review enrolled six prospective studies, 28,862 participants with 3305 cases of MetS, concluded that heavy alcohol consumption was associated with an increased risk of MetS while very light alcohol consumption decreased the risk of Mets [26]. However, in our present study, we are lack of the dose of alcohol that residents took. One interesting finding is that in our study, baseline current smoking was related with lower incidence of MetS at follow-up. It is contrary to many previous studies. We retrospect analyzed the male residents that smoking in baseline, found that they were younger than non-current smokers (53.27 ± 10.02 vs. 55.70 ± 11.12, P < 0.001). Current smoker had relatively lower value of SBP, DBP, WC compared to non-current smokers. Besides, at baseline, current smoker had significantly less number of metabolic disorder than non-current smokers (1.25 ± 0.73 vs. 1.36 ± 0.69, P < 0.001). In all, they might be reasonable that in comparison with current smokers in baseline, non-current smokers had higher risk of MetS in fellow-up. Married male residents in the present seemed have lower incidence of MetS compared with non-married ones. This finding was consistence with the survey among Korean middle-aged women that prevalence of MetS was 30% in the married group and 34.2% in the unmarried group [27].And the possible explanation might be related to the low socioeconomic status among unmarried male in the present study. Those unmarried male were likely to be low income family (51.0% vs. 11.9%, P < 0.001) and higher rate of low educational level (70.6% vs. 41.6% for primary school and under) compared with married male. Accumulative evidence inferred that a low socioeconomic status increased the risk of cardiovascular diseases [28, 29]. In male, the major associated factors of Mets were unhealthy living habit while in female are more likely to be the diet habit. In female, increasing age is a significant risk factors for MetS. Female aged over 65 years had 2.61-fold of risk to have MetS. Besides, consumption of bean and bean product and tea also associated with higher incidence of MetS. This findings are contrary to many previous study held in both human and animal claiming a beneficial effect of tea on metabolic disorders [30–32]. But the specific reasons to explain this inconsistent results in our study are still unclear. Maybe further studies are required to figure out the possible reasons.

The present study has many limitation. First, the incidence of MetS was based on a single blood test which might have bias. Second, we only evaluate whether residents are current smoker or drinker. We did not estimate the exact dose of the smoking and drinking. Hence, there might be bias to conclude that drinking or smoking are risk or beneficial factors of MetS.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the present study estimates the changes of metabolic parameters of residents with MetS at baseline and with the conclusion that many metabolic index did alleviated in follow-up especially the blood pressure. Besides, among residents without MetS at baseline, the cumulative incidence of MetS still high in rural areas of China. The gender discrepancy in the risk factors of MetS help us better knowing what are the major aspects that we should focus on and what can be modulated in order to decrease MetS in rural China.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by grants from the National Key Research and Development Program from the Ministry of Science and Technology of China (Project Grant # 2018 YFC 1312400, Sub-project Grant # 2018 YFC 1312403). Shasha Yu is sponsored by the China Scholarship Council (File No. 201908210044).

Abbreviations

- MetS

Metabolic syndrome

- OR

Odds ratio

- BMI

Body mass index

- SBP

Systolic blood pressure

- DBP

Diastolic blood pressure

- FPG

Fasting plasma glucose

- TC

Total cholesterol

- LDL-C

Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- HDL-C

High-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- TG

Triglyceride

- eGFR

Estimated glomerular filtration rate

Authors’ contributions

SY contributed to the data collection, analysis and interpretation. XG and HY contributed to data collection. GL and SY contributed to data analysis. YS contributed to the study conceptions and design. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

No

Availability of data and materials

Enquiries regarding the availability of primary data should be directed to the principal investigator Professor Yingxian Sun (sunyingxiancmu1h@163.com).

Ethics approved and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of China Medical University (Shenyang, China AF-SDP-07-1, 0-01). All procedures were performed in accordance with ethical standards. Written consent was obtained from all participants after they had been informed of the objectives, benefits, medical items and confidentiality agreement regarding their personal information.

Consent for publication

All the participants gave consent for direct quotes from their interviews to be used in this manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Rochlani Y, Pothineni NV, Kovelamudi S, Mehta JL. Metabolic syndrome: pathophysiology, management, and modulation by natural compounds. Ther Adv Cardiovasc Dis. 2017;11(8):215–225. doi: 10.1177/1753944717711379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Samson SL, Garber AJ. Metabolic syndrome. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2014;43(1):1–23. doi: 10.1016/j.ecl.2013.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee JA, Yoo JE, Park HS. Metabolic syndrome and incidence of breast cancer in middle-aged Korean women: a nationwide cohort study. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2017;162(2):389–393. doi: 10.1007/s10549-017-4131-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mitaki S, Takayoshi H, Nakagawa T, Nagai A, Oguro H, Yamaguchi S. Metabolic syndrome is associated with incidence of deep cerebral microbleeds. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(3):e194182. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0194182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chang CH, Yeh YC, Caffrey JL, Shih SR, Chuang LM, Tu YK. Metabolic syndrome is associated with an increased incidence of subclinical hypothyroidism—a cohort study. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):6754. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-07004-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang Y, Mi J, Shan XY, Wang QJ, Ge KY. Is China facing an obesity epidemic and the consequences? The trends in obesity and chronic disease in China. Int J Obes (Lond) 2007;31(1):177–188. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.National Center For Health Statistics DOHI, Statistics. crude and age-adjusted percentage of Civilian NAWD, Promotion EAGC, Prevention DODT.

- 8.Latifi SM, Karandish M, Shahbazian HB, Chinipardaz R, Sabet A, Pirani N. A survey of the incidence of dyslipidemia and its components in people over 20 years old in Ahvaz: a cohort study 2009–2014. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2017;11(Suppl 2):S751–S754. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2017.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yu S, Guo X, Yang H, Zheng L, Sun Y. An update on the prevalence of metabolic syndrome and its associated factors in rural northeast China. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:877. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li Z, Guo X, Zheng L, Yang H, Sun Y. Grim status of hypertension in rural China: results from Northeast China Rural Cardiovascular Health Study 2013. J Am Soc Hypertens. 2015;9(5):358–364. doi: 10.1016/j.jash.2015.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.World Health Organization IAFT.

- 12.Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, Cushman WC, Green LA, Izzo JJ, Jones DW, Materson BJ, Oparil S, Wright JJ, et al. The Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure: the JNC 7 report. JAMA. 2003;289(19):2560–2572. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.19.2560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, Zhang YL, Castro AR, Feldman HI, Kusek JW, Eggers P, Van Lente F, Greene T, et al. A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150(9):604–612. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-9-200905050-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alberti KG, Eckel RH, Grundy SM, Zimmet PZ, Cleeman JI, Donato KA, Fruchart JC, James WP, Loria CM, Smith SJ. Harmonizing the metabolic syndrome: a joint interim statement of the International Diabetes Federation Task Force on Epidemiology and Prevention; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; American Heart Association; World Heart Federation; International Atherosclerosis Society; and International Association for the Study of Obesity. Circulation. 2009;120(16):1640–1645. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sakurai T, Iimuro S, Araki A, Umegaki H, Ohashi Y, Yokono K, Ito H. Age-associated increase in abdominal obesity and insulin resistance, and usefulness of AHA/NHLBI definition of metabolic syndrome for predicting cardiovascular disease in Japanese elderly with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Gerontology. 2010;56(2):141–149. doi: 10.1159/000246970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tian Y, Jiang C, Wang M, Cai R, Zhang Y, He Z, Wang H, Wu D, Wang F, Liu X, et al. BMI, leisure-time physical activity, and physical fitness in adults in China: results from a series of national surveys, 2000–14. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2016;4(6):487–497. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(16)00081-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Davis CR, Hodgson JM, Woodman R, Bryan J, Wilson C, Murphy KJ. A Mediterranean diet lowers blood pressure and improves endothelial function: results from the MedLey randomized intervention trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2017;105(6):1305–1313. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.116.146803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Esposito K, Giugliano D. Mediterranean diet and type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2014;30(Suppl 1):34–40. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.2516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hassannejad R, Kazemi I, Sadeghi M, Mohammadifard N, Roohafza H, Sarrafzadegan N, Talaei M, Mansourian M. Longitudinal association of metabolic syndrome and dietary patterns: a 13-year prospective population-based cohort study. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2018;28(4):352–360. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2017.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fabiani R, Naldini G, Chiavarini M. Dietary patterns and metabolic syndrome in adult subjects: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutrients. 2019;11(9):2056. doi: 10.3390/nu11092056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cifkova R, Krajcoviechova A. Dyslipidemia and cardiovascular disease in women. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2015;17(7):609. doi: 10.1007/s11886-015-0609-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Choi Y, Chang Y, Kim BK, Kang D, Kwon MJ, Kim CW, Jeong C, Ahn Y, Park HY, Ryu S, et al. Menopausal stages and serum lipid and lipoprotein abnormalities in middle-aged women. Maturitas. 2015;80(4):399–405. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2014.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sun H, Liu Q, Wang X, Li M, Fan Y, Song G, Liu Y. The longitudinal increments of serum alanine aminotransferase increased the incidence risk of metabolic syndrome: a large cohort population in China. Clin Chim Acta. 2019;488:242–247. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2018.10.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pimenta AM, Bes-Rastrollo M, Sayon-Orea C, Gea A, Aguinaga-Ontoso E, Lopez-Iracheta R, Martinez-Gonzalez MA. Working hours and incidence of metabolic syndrome and its components in a Mediterranean cohort: the SUN project. Eur J Public Health. 2015;25(4):683–688. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/cku245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sarebanhassanabadi M, Mirhosseini SJ, Mirzaei M, Namayandeh SM, Soltani MH, Pakseresht M, Pedarzadeh A, Baramesipour Z, Faraji R, Salehi-Abargouei A. Effect of dietary habits on the risk of metabolic syndrome: Yazd Healthy Heart Project. Public Health Nutr. 2018;21(6):1139–1146. doi: 10.1017/S1368980017003627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sun K, Ren M, Liu D, Wang C, Yang C, Yan L. Alcohol consumption and risk of metabolic syndrome: a meta-analysis of prospective studies. Clin Nutr. 2014;33(4):596–602. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2013.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jung YA, Kang LL, Kim HN, Park HK, Hwang HS, Park KY. Relationship between Marital Status and Metabolic Syndrome in Korean Middle-Aged Women: the Sixth Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (2013-2014) Korean J Fam Med. 2018;39(5):307–312. doi: 10.4082/kjfm.17.0020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Busija L, Tao LW, Liew D, Weir L, Yan B, Silver G, Davis S, Hand PJ. Do patients who take part in stroke research differ from non-participants? Implications for generalizability of results. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2013;35(5):483–491. doi: 10.1159/000350724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Clark AM, DesMeules M, Luo W, Duncan AS, Wielgosz A. Socioeconomic status and cardiovascular disease: risks and implications for care. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2009;6(11):712–722. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2009.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Razavi BM, Lookian F, Hosseinzadeh H. Protective effects of green tea on olanzapine-induced-metabolic syndrome in rats. Biomed Pharmacother. 2017;92:726–731. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2017.05.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Teng Y, Li D, Guruvaiah P, Xu N, Xie Z. Dietary supplement of large yellow tea ameliorates metabolic syndrome and attenuates hepatic steatosis in db/db Mice. Nutrients. 2018;10(1):75. doi: 10.3390/nu10010075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li X, Wang W, Hou L, Wu H, Wu Y, Xu R, Xiao Y, Wang X. Does tea extract supplementation benefit metabolic syndrome and obesity? Clin Nutr: A systematic review and meta-analysis; 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Enquiries regarding the availability of primary data should be directed to the principal investigator Professor Yingxian Sun (sunyingxiancmu1h@163.com).