The number of people infected with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 has exponentially increased worldwide1 and coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is officially a pandemic. On February 21th, 2020, the first person-to-person transmission was reported in Italy and since then the infection chain has led to one of the largest COVID-19 outbreaks outside Asia to date. All started and spread in the Lombardy region, the most populated region in Italy (10.2 million of inhabitants), with an outbreak accounting for most of the Italian registered cases of COVID-19, thousands of hospitalized patients, 15% of whom required an admission in intensive care units.2 Such a tsunami of acute patients punched the hospital system in a matter of 4 weeks, and forced the largest part of the region healthcare resources (3.2 beds/1000 inhabitants) to be reconverted into COVID-units, with consequent dramatic imbalance between supply and demand for most nonurgent medical and surgical diseases.3,4 In particular, most patients with solid cancer awaiting surgical intervention had their surgery delayed indefinitely. The current regional model of prioritization in surgical oncology, based on the “first-come, first-served” principle and able to guarantee an average waiting time of 40 days for elective gastrointestinal surgery in the pre-COVID era, had necessarily to be revised.

In such circumstances, the aim of the intervention we were asked to work on was 2-fold: (a) guarantee a hospital-based system for surgical oncology interventions and (b) design a unit-based priority system for cancer patients eligible to surgical intervention.

With respect to the first aim, the regional government selected a few hospitals able to remain relatively COVID-free, thanks to the implementation of restricted infectious triage protocols and intentional closure of emergency access. By means of a hub-and-spoke model the COVID-transformed hospitals with cancer patients in need of surgery could then refer to a full steam cancer-hub in which case discussion and possible interventions could be continued.

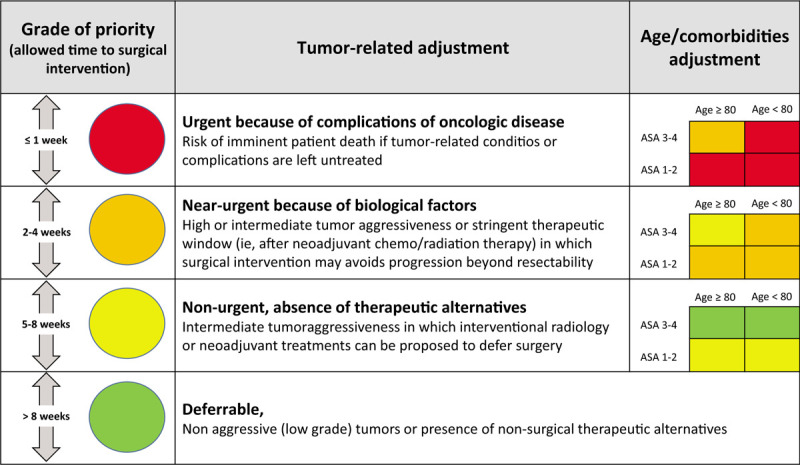

With respect to the second aim, we proposed a renowned system of priority for patients with gastrointestinal malignancies (about 1 quarter of the surgical volume for oncological indications)5 largely drawn from organ transplant allocation principles, namely from the longstanding area of surgery in which the imbalance between demand and supply is permanent.6,7 Here we share the framework that guided our work and the introduction of the model in the Lombardy region, in the hope that it could act as a positive influence for other regions possibly facing similar pandemic. The framework is outlined in Fig. 1 and identifies the priorities as in a traffic light model:

FIGURE 1.

Model of combined approach to priorities of Surgical Oncology during the COVID-19 epidemic. COVID-19 indicates coronavirus disease 2019.

-

-

Red category: urgent because of cancer-related clinical conditions and complications. These are patients lacking any therapeutic alternative and; therefore, at risk of dying within few hours/few days if not surgically treated. Examples are: gastric tumors presenting with uncontrollable bleeding, pancreatic tumors with obstructive jaundice in which endoscopic palliation has failed, intestinal obstruction from tumors of the right colon and tumor perforation.

-

-

Orange category: nearly-urgent because of negative cancer-related biologic factors. These are patients for whom tumor aggressiveness or stringent therapeutic window (for instance at the end of neoadjuvant chemoradiation therapy) mandate surgical intervention within few weeks, because of the risk of progression beyond resectability. In these patients the risk of progression equates the risk of death in the near future, and the net benefit of surgery is expected to be very high. Examples are resectable mass-forming cholangiocarcinoma or gallbladder cancer or locally advanced rectal cancer. The orange group also includes tumors in which progressive or stable disease following neoadjuvant treatments seems still resectable (ie, colorectal liver metastases, lymph node-positive gastric cancer, pancreatic adenocarcinoma).

-

-

Yellow category: nonurgent because of positive biologic factors in the absence of nonsurgical alternatives. In these patients, the biological behavior of disease is not particularly aggressive, but no therapeutic alternatives nor neoadjuvant treatments allowing surgery to be deferred are available. The risk of progression during waiting time is relatively low and does not imply a risk of death in a short time, whereas the expected outcome after surgery is generally good, thus maintaining a high net benefit of delayed surgery. Examples are: T1b-T2 N0 gastric cancers, most of hepatocellular carcinomas, <T3 colorectal cancers. In this category, tumors following neoadjuvant treatments with partial/complete response are also included (ie, colorectal liver metastases, lymph node-positive gastric cancer etc); patients who progress during the delayed waiting time should be reclassified into the orange group.

-

-

Green category: nonaggressive tumors or deferrable because of presence of nonsurgical alternatives. These are: (1) patients for whom surgery might be indicated, but in which alternative non-surgical treatments have demonstrated nearly equal survival outcomes (ie, T1a gastric cancers, single hepatocellular carcinoma <2 cm etc); (2) tumors in which surgical outcomes would be comparable or even better if neoadjuvant treatments were used to delay surgery (ie, borderline resectable pancreatic tumors, >T2N1 asymptomatic gastric adenocarcinoma, colorectal liver metastases etc); (3) patients within tumor node metastases staging system stage 1 or bearing biologically low aggressive cancers (ie, neuroendocrine tumors, asymptomatic gastrointestinal stromal tumors, pancreatic intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms). As for the previous category, green patients who progress during waiting time would be reclassified into the yellow class.

To each category, a variable time frame for surgical intervention was arbitrarily assigned (see Fig. 1). The entire framework was based on the following principles:

We thought of utmost importance that even under the current severe imbalance between demand and supply, surgical indications in patients with cancer of the gastrointestinal tract should not deviate from what is supported by scientific evidence.

A shift from a model aimed at doing everything possible to save every life to a model aimed at maximizing the number of lives saved8 was needed. Because oncological patients are rarely an urgent indication to surgery, the principle of “the sickest first” – which implies prioritizing those with the worst future prospects if left untreated – remained applicable only to selected cases, identified by the red category.

The concept of survival benefit informed the rest of the model. Survival benefit is the survival gain offered by a given therapy (in this case surgery) in comparison with the best alternative option (in this case delayed surgery or palliative treatments). This principle, widely used in organ transplantation,9 has the potential of maximizing the total years of life gained when applied to a population of similar patients in need of surgical intervention.10 We framed the orange, yellow, and green categories according to this principle, considering that priority of surgical intervention decreases in parallel with the net health benefit expected in each group.

As surgical intensive care units play an essential role in determining the outcome of patients both in the surgical oncology scenario and for COVID19-related complications, allocation to surgery during the pandemic is prone to disfavor those who are more likely to require a prolonged surgical intensive care units stay. To provide objective measures for decision-making we propose to consider the preoperative American Society of Anaesthesiologists score and age cut-offs (in our region arbitrarily set at 80 years). As presented in Fig. 1, red and orange patients who are ≥80 years old and/or with the American Society of Anaesthesiologists score ≥3 are downgraded to next category, and yellow patients with similar preoperative risk.

As definition of surgical complexity is an operator-dependent variable coupled with resource availability and hospital volumes, we felt that the risk of unfair discrimination would be in place if surgical burden was used as a universal priority variable. For instance, procedures related to pancreatic head, esophageal or retroperitoneal cancers are defined as complex in almost all cases.

In conclusion, an allocation scheme of priority for surgical oncology is proposed to face the dramatic restrictions in elective surgery resources during the COVID19 pandemic. We aimed at maintaining surgical indications whereas optimizing allocation and prioritization according to the survival benefit principle. The proposed framework has been adopted for patients with cancer of the gastrointestinal tract, but can be easily extended to most of other fields of surgical oncology. Only time will tell how it works.

Footnotes

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1. WHO - World Health Organization: Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Pandemic [Internet]. World Heal Organ. 2020. Available at: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019. Accessed April 10, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ministero della Salute [Internet] [cited 2020 Apr 6] Available at: http://www.salute.gov.it/portale/nuovocoronavirus/dettaglioContenutiNuovoCoronavirus.jsp?id=5351&area=nuovoCoronavirus&menu=vuoto. Accessed April 10, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Spina S, Marrazzo F, Migliari M, et al. The response of Milan's Emergency Medical System to the COVID-19 outbreak in Italy. Lancet 2020; 395:e49–e50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grasselli G, Pesenti A, Cecconi M. Critical care utilization for the COVID-19 outbreak in Lombardy, Italy: early experience and forecast during an emergency response. JAMA 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ministero della salute – Agenzia Nazionale per i Servizi Sanitari Regionali – Programma Nazionale esiti. [Internet] [cited 2020 Apr 6] Available at: https://pne.agenas.it/PNEed17/index.php. Accessed April 10, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mazzaferro V. Squaring the circle of selection and allocation in liver transplantation for HCC: an adaptive approach. Hepatology 2016; 63:1707–1717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cillo U, Burra P, Mazzaferro V, et al. A multistep, consensus-based approach to organ allocation in liver transplantation: toward a “blended principle model”. Am J Transplant 2015; 15:2552–2561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Persad G, Wertheimer A, Emanuel EJ. Principles for allocation of scarce medical interventions. Lancet 2009; 373:423–431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Merion RM, Schaubel DE, Dykstra DM, et al. The survival benefit of liver transplantation. Am J Transplant 2005; 5:307–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vitale A, Volk M, Cillo U. Transplant benefit for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol 2013; 19:9183–9188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]