Abstract

Coronavirus Disease 2019 (Covid-19) is an active pandemic that has required rapid conversion of practice patterns to mitigate disease spread. Although recommendations have been released for physicians to postpone elective procedures, the utility of common physiatry procedures and their infectious risk profile have yet to be clearly delineated. In this article, we describe an update on existing national recommendations and outline considerations as practitioners and institutions strive to meet the needs of patients with disabilities.

KEYWORDS/Glossary of terms: physiatry, procedures, coronavirus, Covid-19, Coronavirus Disease 2019 (Covid-19), Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), personal protective equipment (PPE) , World Health Organization (WHO), American Medical Association (AMA), Nerve conduction study (NCS), Electromyography (EMG) , American Association of Neuromuscular & Electrodiagnostic Medicine (AANEM)

Background

With the ongoing Coronavirus Disease 2019 (Covid-19) pandemic, efforts to mitigate disease spread by minimizing communal contact are vital1–3. In March 2020, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) have released recommendations urging clinicians to postpone elective procedures and utilize telemedicine for ambulatory care4,5. However, the response by many healthcare providers and settings, especially with elective procedures, continues to be heterogeneous6,7. In particular, the utility of common point of care physiatry procedures and their associated risk profiles during the Covid-19 pandemic need further clarification.

Infectious spread

Covid-19 is caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome from novel coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), which is a respiratory virus presumed to be primarily spread via droplet contact8,9. Viral spread occurs via exposure of the nasopharyngeal mucosa and respiratory tract directly to micro-droplets expelled during coughing and/or sneezing by infected individuals or indirectly via self-inoculation of micro-droplets from contaminated surfaces onto the nasopharyngeal and oropharyngeal mucosa. To this end, rescheduling elective medical visits and procedures, implementing careful screening and quarantining protocols for potentially infectious patients and personnel, proper handwashing and equipment cleaning practices, and judiciously yet appropriately using personal protective equipment (PPE) can reduce viral transmission and potentially reduce Covid-19 related deaths4,5,10,11.

General Considerations and National Guidelines

The CDC and CMS recently released recommendations that all elective and non-essential medical, surgical, and dental procedures be deferred in an attempt to optimize use of healthcare equipment and resources amidst the Covid-19 pandemic4,5. The overarching aims for the current national recommendations are four-fold: (1) to preserve personal protective equipment (PPE), inpatient beds, and ventilators; (2) to ensure that the healthcare workforce is available to care for patients most in need; (3) to encourage patients to remain home as much as possible to limit exposure; and (4) to provide a framework for triaging non-essential surgeries and procedures. As an illustration of this framework, CMS provides examples of common elective procedures with division into tiers and recommendations for scheduling based on associated patient and procedural risks5. However, these tiered procedural recommendations largely focus on invasive and/or surgical procedures and make scant reference to minimally-invasive and non-invasive procedures, which comprise the vast majority of general physiatry procedures in which earlier intervention can optimize recovery and reduce cost-burden.

Beyond these recommendations, both the CDC and CMS agree that decisions about proceeding with non-essential surgeries and procedures will be made at the local level by the clinician, patient, hospital, and state and local health departments4,5. Physiatry based procedures are unique in that their overall goals are to allow for functional independence; this is particularly important in such times as we try to reduce the functional decline in our vulnerable patient population10,12. Most physiatry procedures are performed on an outpatient basis and so do not directly impact the availability of valuable hospital resources needed to care for inpatients. Use of PPE is an important consideration and varies based on procedural and patient risk factors, which will be discussed further below.

While most physiatry procedures are considered elective, this designation does not suggest that they are unnecessary, but rather are not time-sensitive in nature. Given the current status of national recommendations - practitioners have a level of autonomy in deciding which patients may be appropriate candidates for a non-emergent or non-life sustaining procedures4,5. Therefore, blanket protocols to terminate all ambulatory could introduce barriers for persons with disabilities for whom timely physiatric care can be vital to their health and function10,12.

Persons with disabilities are medically vulnerable given their associated impairments10. Furthermore, they often require several accommodations ranging from caregiver and nursing support to transportation arrangements. As such, measures to mitigate healthcare interruptions are vital. In their recent report for disability considerations during the Covid-19 outbreak, the World Health Organization (WHO) states that barriers to health care are likely increased for persons with disabilities10. The CDC, CMS, and the American Medical Association (AMA) have advocated for the use of telemedicine to provide ambulatory care, when possible5,6,13. The WHO specifically recommends telemedicine as a means to decrease barriers to ambulatory care for persons with disabilities10. Additionally, telemedicine may provide a unique opportunity to stratify procedural urgency and identify appropriate procedural candidates.

Procedural stratification

Common point of care physiatry procedures include, but are not limited to14:

pain and musculoskeletal procedures such as joint, peripheral nerve, epidural injections, and trigger point injections

spasticity procedures such as chemodenervation and neurolysis

electrodiagnostic procedures such as nerve conduction (NCS) and electromyography (EMG) studies

The elective nature and time sensitivity of these procedures has understandably come into question. While no clearly delineated recommendations from governmental health agencies or major medical societies exist, considering the urgency and indication of each procedure on a case-by-case basis is instrumental. As previously mentioned, the use of telemedicine services in the Covid-19 pandemic, as extensively endorsed by the CDC, CMS, AMA, and WHO, may help to stratify procedural urgency in patients pending elective procedures5,6,10,13. We would like to more fully consider the elective and functionally driven nature of physiatry procedures, as well as their time sensitivity.

Elective

There exist purely elective procedures in chronic conditions that can be rescheduled without meaningful functional impairment or patient risk. While elective physiatry procedures may not carry life-sustaining benefits, they can provide meaningful improvements in pain (Table 1, Row 1). Consequently, if deferred long enough, some patients may resort to urgent care or emergency rooms to address uncontrolled pain. Given the overwhelming estimates of expected respiratory illnesses and healthcare demands in the United States in the coming weeks and months, measures to decrease the burden of preventable emergency room visits and hospital admissions is highly desirable15. Judicious use of elective pain-management procedures in the clinic setting for certain at-risk patients may prove useful to decrease unnecessary emergency room visits. A recent paper by Cohen et al. also support these sentiments as they list several considerations for triaging pain management options which include likelihood of patients seeking emergency room services, be started on opiates, functional detriment, acuity, and work status16.

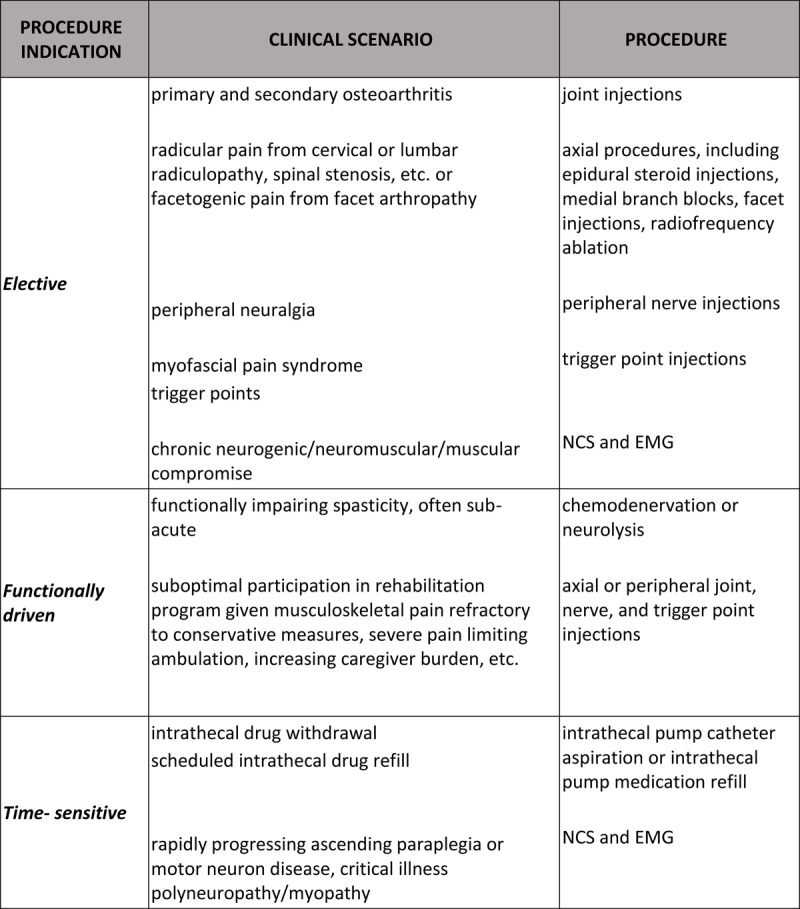

TABLE 1.

Clinical scenarios and physiatry procedures based on elective, functionally driven, or time-sensitive indications.

Functionally driven

Much uncertainty exists with time insensitive, “functionally driven” procedures that may optimize functional recovery or capacity in certain patients (Table 1, Row 2). Similar to the previously discussed elective procedures, these procedures do not carry lethal implications if not performed. However, these procedures can offer or facilitate significant functional benefit and mitigate sequelae like falls or pressure wounds.

Early and goal-directed spasticity management has been shown to facilitate motor recovery and functional gains17,18. Patients with chronic spasticity may necessitate timely chemodenervation or neurolysis to facilitate body positioning, enhance motor capacity, enable hygiene care, prevent contractures, and even provide pain relief17–19. Pain management procedures in the inpatient and subacute rehabilitation settings may enhance patient participation and optimize their use of limited inpatient rehabilitation time. Patients with chronic pain may also benefit from timely peripheral joint, nerve, or trigger point injections for analgesic benefit that may accelerate mobility and function20–22. Notably, the procedural driven analgesic benefit in the chronic pain population may prevent risk of opiate diversion or misuse, which may result in respiratory compromise that can be particularly dangerous with concomitant Covid-19 infection23. It should be noted that articular corticosteroid injections have been shown to increase influenza risk and so too may increase the risk of contracting Covid-1924. Therefore, careful consideration of patients’ immune status is imperative prior to peripheral corticosteroid administration.

An additional concern is that if these procedures are deferred, worsening impairments will increase dependence on caregivers and increase the vulnerability of disabled patients during the staffing limitations and social distancing associated with the pandemic11,13. Therefore, physiatrists may consider performing functionally driven procedures in appropriate patient candidates who are deemed to have discrete functional goals. Appropriate patient and procedure specific infectious prevention measures should be undertaken.

Time-sensitive

There are also time-sensitive physiatry procedures for which procedural benefits may include a reduction in mortality, morbidity, or immediate disease burden25–27. Such procedures should continue to be performed given their importance in providing timely diagnostic and therapeutic benefit (Table 1, Row 3).

Patients with intrathecal therapies are susceptible to a host of complications with interruptions to intrathecal drug delivery26,27. While withdrawal from intrathecal opiates can be unpleasant for patients and can require inpatient monitoring, withdrawal phenomena from intrathecal clonidine and baclofen can be life-threatening. Thus, it is imperative to ensure that patients with intrathecal pump systems have timely refills to avoid risk of drug withdrawal. Additionally, those patients with suspected intrathecal drug delivery dysfunction require timely device interrogation, troubleshooting, possible catheter assessment, and rescue enteral medications.

Electrodiagnostic studies can be vital for adding diagnostic and prognostic benefit in persons with suspected neurogenic, neuromuscular, or muscular disorders25,28. While affected patients can vary in presentation, clinical concern for rapidly progressing paraparesis/paraplegia, motor neuron disease, and critical illness neuropathy/myopathy are some of most common reasons for inpatient NCS and EMG studies. Information gleaned from these studies can alter clinical management, which can be time-sensitive depending on the severity of the condition. In a single center study of 98 inpatient procedures, Perry et al. found that EMG and NCS studies yielded a clinically relevant and new diagnosis in 13% of cases and altered treatment decisions in 17% of cases25. Since NCS/EMG studies involved prolonged patient contact and thus increased potential exposure, the American Association of Neuromuscular & Electrodiagnostic Medicine (AANEM) recommends deferral of electrodiagnostic studies in cases of confirmed or suspected Covid-19 or recent exposures unless necessary for management29. In these cases, practitioners must wear appropriate PPE as allocated by their institution12,30.

Patient and procedure specific risks

Despite implementation of recommended preventative measures, the risk of Covid-19 exposure or infection is likely increased with certain patients and procedures (Table 2)11,13. In higher risk cases, proper prophylactic considerations must be taken so as to meaningfully minimize the risk of spread among the patient, physician, and supportive personnel11,13,30,31. Such considerations are especially necessary in persons with disability as they are often at a higher risk for disease- related morbidity and mortality11,13.

TABLE 2.

High risk clinical scenarios and prophylactic considerations based on procedure specific risks.

Additionally, careful consideration is warranted for procedures where multiple direct patient encounters are necessary. Such scenarios which include diagnostic nerve blocks to be followed by neuroablative procedures i.e. phenol neurolysis, radiofrequency ablation, etc. or series of viscosupplementation understandably confer increased patient and practitioner risk given recurrent interactions. Given that meaningful or durable analgesic or functional benefit in such instances may only be fully achieved after completion of these procedural protocols, practitioners should carefully weigh the potential benefit of these procedures against the amplified risks posed to patients and physicians with recurrent encounters. Recently, the American Society of Interventional Pain Physicians has released risk stratification guidelines to help characterize patients at increased risk of COVID associated morbidity34. While not substantiated, such resources can be instrumental in helping identify and exclude procedural candidates.

Conclusion

The uncertainty of Covid-19 associated disease burden has led to rapidly changing clinical practices and recommendations. The intent of our commentary is to provide an update on existing national recommendations and outline considerations as practitioners and institutions strive to make wise decisions at the local and individual level for physiatric practices. Given global and national disparities in healthcare resources, rehabilitation care models, and Covid-19 prevalence and healthcare burden, these decisions are inherently complex and individualized.

While the CDC and CMS recommend for elective procedures to be rescheduled in order to preserve healthcare resources and personnel, these recommendations do not account for the spectrum of physiatry procedures and the uniquely vulnerable population we serve. A more nuanced approach that takes procedure and patient specific risks into account will facilitate a more individualized approach to balancing the competing concerns of preserving PPE, protecting both medical staff and patients from Covid-19 exposure and infection, and continuing to provide high-quality care for conditions that substantially impact quality of life and function.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES: This was an unfunded study and the authors have no relevant financial interests to disclose.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS:

JK: This author helped with project inception, literature review, and writing

MS: This author helped with project inception, literature review, and writing

MVG: This author helped with writing and project supervision

PJ: This author helped with writing and project supervision

References

- 1.Anderson RM, Heesterbeek H, Klinkenberg D, Hollingsworth TD. How will country-based mitigation measures influence the course of the COVID-19 epidemic?. The Lancet. 2020;395:931–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.del Rio C, Malani PN. COVID-19—new insights on a rapidly changing epidemic. JAMA. 2020; February 28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fauci AS, Lane HC, Redfield RR. Covid-19—Navigating the Uncharted. New England Journal of Medicine. 2020;382:1268–1269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention CDC Recommendation: Postpone Non-Urgent Dental Procedures, Surgeries, and Visits. https://www.cdc.gov/oralhealth/infectioncontrol/statement-COVID.html. Published March 27, 2020. Accessed March 27, 2020.

- 5.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services CMS Releases Recommendations on Adult Elective Surgeries, Non-Essential Medical, Surgical, and Dental Procedures During COVID-19 Response. https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/press-releases/cms-releases-recommendations-adult-elective-surgeries-non-essential-medical-surgical-and-dental. Published March 18, 2020. Accessed March 27, 2020.

- 6.Butler D. People are still getting tummy tucks and cataract surgeries - and health-care workers fear it puts all at risk for coronavirus. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/nation/2020/03/20/coronavirus-elective-surgeries/. Published March 20, 2020. Accessed March 27, 2020.

- 7.Zezima K. People are still getting tummy tucks and cataract surgeries - and health-care workers fear it puts all at risk for coronavirus. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/nation/2020/03/20/coronavirus-elective-surgeries/. Published March 20, 2020. Accessed March 26, 2020.

- 8.Lipsitch M, Swerdlow DL, Finelli L. Defining the epidemiology of Covid-19—studies needed. New England Journal of Medicine. 2020;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Adams JG, Walls RM. Supporting the Health Care Workforce During the COVID-19 Global Epidemic. JAMA. 2020;3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.World Health Organization Disability considerations during the COVID-19 outbreak. https://www.who.int/internal-publications-detail/disability-considerations-during-the-covid-19-outbreak. Published March 26, 2020. Accessed March 27, 2020.

- 11.Abd-Elsayed AA, Karri J. Utility of Substandard Facemask Options for Healthcare Workers in the Covid 19 Pandemic. Anesthesia and Analgesia. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McNeary L, Maltser S, Verduzco-Gutierrez M. Navigating Coronavirus Disease 2019 (Covid-19) in Physiatry: A CAN report for Inpatient Rehabilitation Facilities. PM&R. 2020; March 20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.American Medical Association Providing patient care remotely in a pandemic. https://www.ama-assn.org/delivering-care/ethics/providing-patient-care-remotely-pandemic. Published March 18, 2020. Accessed March 27, 2020.

- 14.American Academy of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation What Types of Treatments and Procedures Do Physiatrists Perform. https://www.aapmr.org/career-center/medical-student-resources/a-medical-students-guide-to-pm-r/what-types-of-treatments-and-procedures-do-physiatrists-perform. Accessed March 27, 2020.

- 15.IHME COVID-19 health service utilization forecasting team Forecasting COVID-19 impact on hospital bed-days, ICU-days, ventilator days and deaths by US state in the next 4 months. MedRxiv. 6 March2020. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cohen SP, Baber ZB, Buvanendran A, McLean LT, Chen Y, Hooten WM, Laker SR, Wasan WA, Kennedy DJ, Sandbrink F, King LT. Pain Management Best Practices from Multispecialty Organizations during the COVID-19 Pandemic and Public Health Crises. Pain Medicine. 2020. April 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li S. Spasticity, motor recovery, and neural plasticity after stroke. Frontiers in neurology. 2017. April 3;8:120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Karri J, Zhang B, Li S. Phenol Neurolysis for Management of Focal Spasticity in the Distal Upper Extremity. PM&R. 2019. July 6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Karri J, Mas MF, Francisco GE, Li S. Practice patterns for spasticity management with phenol neurolysis. Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine. 2017. June 28;49:482–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wehling P, Evans C, Wehling J, Maixner W. Effectiveness of intra-articular therapies in osteoarthritis: a literature review. Therapeutic advances in musculoskeletal disease. 2017. August;9:183–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aeschbach A, Mekhail NA. Common nerve blocks in chronic pain management. Anesthesiology Clinics of North America. 2000. June 1;18:429–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cotchett MP, Munteanu SE, Landorf KB. Effectiveness of trigger point dry needling for plantar heel pain: a randomized controlled trial. Physical therapy. 2014. August 1;94:1083–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Volkow N, National Institute on Drug Abuse. COVID-19: Potential Implications for Individuals with Substance Use Disorders. https://www.drugabuse.gov/about-nida/noras-blog/2020/03/covid-19-potential-implications-individuals-substance-use-disorders. Published March 24, 2020. Accessed March 27, 2020.

- 24.Sytsma TT, Greenlund LK, Greenlund LS. Joint Corticosteroid Injection Associated With Increased Influenza Risk. Mayo Clinic Proceedings: Innovations, Quality & Outcomes. 2018. June 1;2:194–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Perry DI, Tarulli AW, Nardin RA, Rutkove SB, Gautam S, Narayanaswami P. Clinical utility of electrodiagnostic studies in the inpatient setting. Muscle & Nerve. 2009. August;40:195–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Coffey RJ, Edgar TS, Francisco GE, Graziani V, Meythaler JM, Ridgely PM, Sadiq SA, Turner MS. Abrupt withdrawal from intrathecal baclofen: recognition and management of a potentially life-threatening syndrome. Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation. 2002. June 1;83:735–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Noon K, Wallace M, Furnish T. Intrathecal Medication Withdrawal. In: Challenging Cases and Complication Management in Pain Medicine 2018 (pp. 203-209). Springer, Cham. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ney JP, Davidson HL. Inpatient Electromyography: Benefits and Limitations for the Hospital Evaluation of Neuromuscular Disorders. Acute Care. 2006. April;52. [Google Scholar]

- 29.American Association of Neuromuscular & Electrodiagnostic Medicine COVID-19: Guidance for AANEM Members. https://www.aanem.org/Practice/COVID-19-Guidance. Accessed March 27, 2020.

- 30.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Interim Guidance for Healthcare Facilities: Preparing for Community Transmission of COVID-19 in the US. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/healthcare-facilities/guidance-hcf.html. Published February 29, 2020. Accessed March 27, 2020.

- 31.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Implementation of Mitigation Strategies for Communities with Local COVID-19 Transmission. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/downloads/community-mitigation-strategy.pdf. Accessed March 27, 2020.

- 32.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Interim U.S. Guidance for Risk Assessment and Public Health Management of Healthcare Personnel with Potential Exposure in a Healthcare Setting to Patients with Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19). https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/guidance-risk-assesment-hcp.html?fbclid=IwAR24sPRluyXo7abdKY4WfUwg4TtckmlqV9AZdMHpC80ZgDyEtqqwxb0baBo. Published March 7, 2020. Accessed March 27, 2020.

- 33.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Environmental Cleaning and Disinfection Recommendations. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/community/organizations/cleaning-disinfection.html. Published March 6, 2020. Accessed March 27, 2020.

- 34.American Society of Interventional Pain Physicians ASIPP Risk Stratification of Patients Presenting for Interventional Pain Procedures: Decreasing Morbidity of COVID-19. http://www.asipp.org/asipp-updates/asipp-breaking-news-april-27-2020. Published April 27, 2020. Accessed April 27, 2020.