Abstract

Objective:

The aim of this study was to clarify the role of pancreatic surgery during the COVID-19 pandemic to optimize patients’ and clinicians’ safety and safeguard health care capacity.

Summary Background Data:

The COVID-19 pandemic heavily impacts health care systems worldwide. Cancer patients appear to have an increased risk for adverse events when infected by COVID-19, but the inability to receive oncological care seems may be an even larger threat, particularly in case of pancreatic cancer.

Methods:

An online survey was submitted to all members of seven international pancreatic associations and study groups, investigating the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on pancreatic surgery using 21 statements (April, 2020). Consensus was defined as >80% agreement among respondents and moderate agreement as 60% to 80% agreement.

Results:

A total of 337 respondents from 267 centers and 37 countries spanning 5 continents completed the survey. Most respondents were surgeons (n = 302, 89.6%) and working in an academic center (n = 286, 84.9%). The majority of centers (n = 166, 62.2%) performed less pancreatic surgery because of the COVID-19 pandemic, reducing the weekly pancreatic resection rate from 3 [interquartile range (IQR) 2–5] to 1 (IQR 0–2) (P < 0.001). Most centers screened for COVID-19 before pancreatic surgery (n = 233, 87.3%). Consensus was reached on 13 statements and 5 statements achieved moderate agreement.

Conclusions:

This global survey elucidates the role of pancreatic surgery during the COVID-19 pandemic, regarding patient selection for the surgical and oncological treatment of pancreatic diseases to support clinical decision-making and creating a starting point for further discussion.

Keywords: ampullary adenocarcinoma, CA19-9, chronic pancreatitis, COVID-19, distal bile duct cancer, duodenal adenocarcinoma, hospital volume, intensive care unit, intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms, minimally invasive surgery, neoadjuvant treatment, pancreatic cancer, pancreatic necrosis, pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor, pancreatic surgery, pandemic, respectability, SARS-CoV-2

The World Health Organization (WHO) declared a pandemic of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) (SARS-CoV-2) on March 11, 2020.1 The rapid spread of COVID-19 infections heavily impacts health care systems worldwide, resulting in limitations in both hospital and intensive care unit (ICU) capacity.2 As a result, this pandemic not only affects COVID-19 patients, but strikes the entire health care system including the care for patients with pancreatic cancer and other pancreatic diseases.3

Recent large series suggest an increased risk for cancer patients to develop severe complications when infected by COVID-19, including those who were treated with surgery or chemotherapy in the last month.4 Pursuing oncological care exposes both health care professionals and vulnerable patients to become infected by COVID-19. However, the inability to receive medical and/or surgical care seems to be an equal threat for cancer patients as well.5 The highly aggressive biology of pancreatic cancer requires the continuation of oncological care during the COVID-19 pandemic,6,7 but an unambiguous strategy is needed to support health care professionals in clinical decision-making.

Therefore, this international survey study aimed to clarify the role of pancreatic surgery during the COVID-19 pandemic through 21 statements, aiming to optimize safety for patients and clinicians, and safeguard health care.

METHODS

Survey

An online survey was designed and submitted to all members of 7 international pancreatic associations and study groups: the Pancreas Club, European Pancreatic Club, Chinese Pancreatic Surgery Association, European Consortium on Minimally Invasive Pancreatic Surgery, Study Group of Preoperative Therapy for Pancreatic Cancer, Study Group of Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma with Peritoneal Metastasis, and International Study Group on Cystic Tumors of the Pancreas using Google Forms (Google LLC, Menlo Park CA). Both surgeons and nonsurgeons (eg, gastroenterologists and medical oncologists) were asked to participate in this survey to balance the discussion.

The survey consisted of 36 questions on baseline characteristics, the local impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on pancreatic surgery (ie, number of pancreatic resections, triage, and screening), and 21 statements about the role of pancreatic surgery in the current era of the COVID-19 pandemic. Each statement had to be appraised using 3 options: agree, disagree, and uncertain. See Text – Supplemental Digital Content 1, for the survey.

The survey was conducted in the first 2 weeks of April 2020. Nonrespondents were reminded twice because of the rapid developments in the current COVID-19 crisis and need for novel policy development a relatively short time window was used. Respondents were asked to register their name and institution to prevent overlap of members between the above-mentioned associations. The response rate could not be calculated since associations submitted the survey themselves. All study procedures were reviewed and approved by the Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board (COMIRB) (protocol #20-0843) at the University of Colorado.

Definitions

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, bile duct cancer, duodenal and ampullary adenocarcinomas, intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms (IPMNs), and pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (pNETs) were defined in accordance to the WHO definitions.8,9 A hospital was defined as a high-volume pancreatic center when performing ≥20 pancreatoduodenectomies annually.10 Consensus was defined as >80% agreement among respondents and moderate agreement was defined as 60% to 80% agreement among them.

Statistical Analysis

Variables were processed and analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Microsoft Windows version 26 (IBM Corp., Orchard Road Armonk, NY). Data were reported as number with percentage or as median with interquartile range (IQR). The weekly volume of pancreatic resections before and during the COVID-19 pandemic was compared, using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test for non-normally distributed variables. Sensitivity analyses were performed to investigate the influence of specialty, the type of center, and continent. Statistical significance was considered as 2-tailed P value <0.050.

RESULTS

Participants

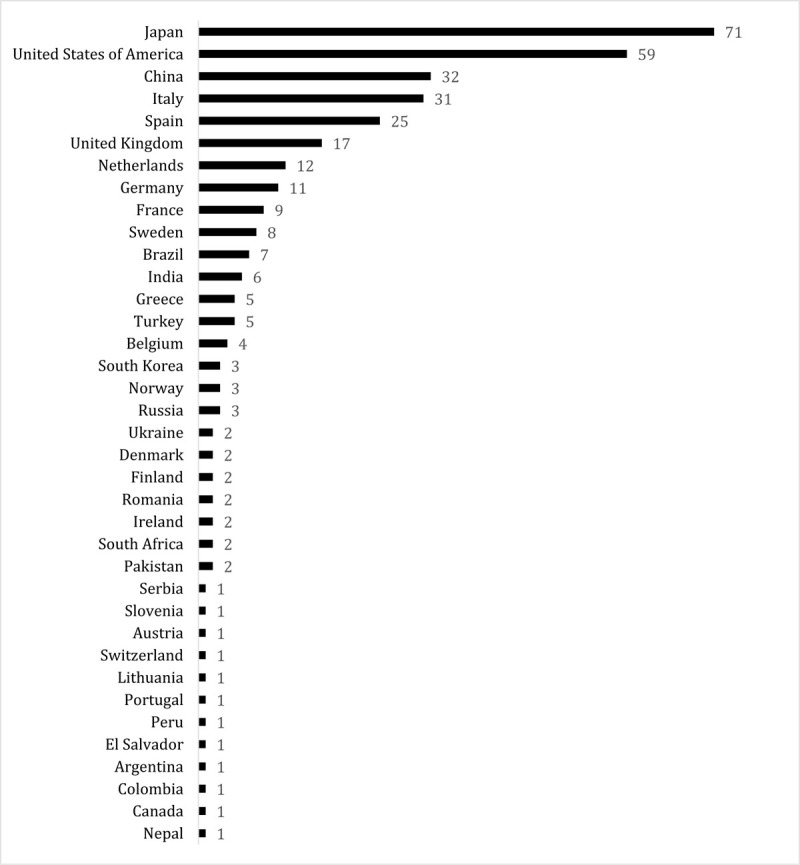

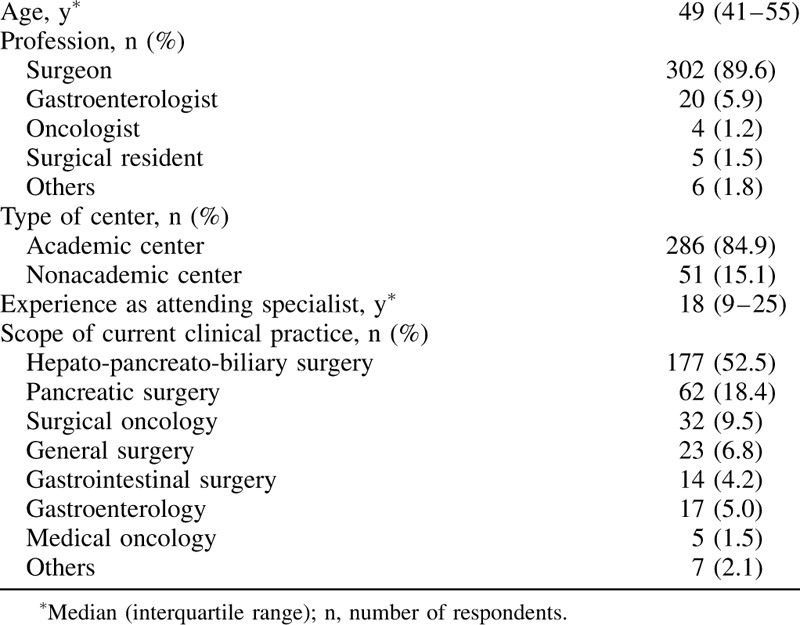

A total of 337 respondents from 267 centers and 37 countries spanning 5 continents completed the online survey. See Figure 1 for the number of responses per country. Most respondents were working in an academic center (n = 286, 84.9%) and the majority of participants were surgeons (n = 302, 89.6%). See Table 1 for the characteristics of the respondents. The median annual hospital and individual surgeon volume of pancreatic resections were 75 (IQR 46–140) and 35 (IQR 20–60), respectively.

FIGURE 1.

Number of responses per country.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of Respondents

Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic

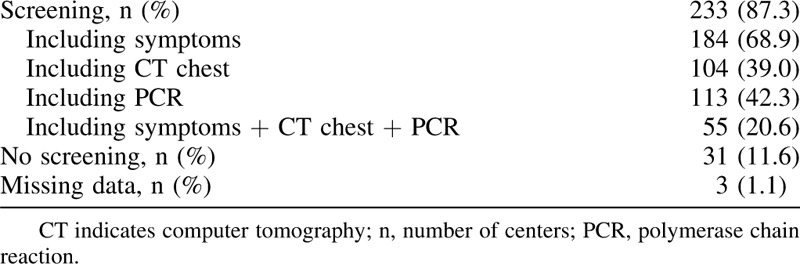

During the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic, 67.8% (n = 181) of centers prioritized between different types of pancreatic resections. Before pancreatic surgery, most centers screened patients for COVID-19 (n = 233, 87.3%), whereas some centers did not (n = 31, 11.6%). See Table 2 for the preoperative COVID-19 screening strategy. The majority of centers (n = 166, 62.2%) performed less pancreatic surgery as consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic. From these centers, the weekly numbers of pancreatic resections decreased from 3 (IQR 2–5) to 1 (IQR 0–2) (P < 0.001). In addition, 30.7% (n = 51) of responding centers performed no pancreatic surgery at all.

TABLE 2.

Preoperative Screening for COVID-19

Statements

Consensus was reached on 13 from the 21 statements (62%) and moderate agreement was achieved on 5 statements (24%). The remaining 3 statements had an agreement <60%. See Tables 3 to 5 for the statement outcomes.

TABLE 3.

Statement Outcomes—Consensus

TABLE 5.

Statement Outcomes——Low Agreement

TABLE 4.

Statement Outcomes—Moderate Agreement

Sensitivity Analyses

The statement outcomes barely changed after excluding the nonacademic centers, without any shifts in the 3 categories of agreement. Exclusion of nonsurgeons lead to the movement of statement 5—regarding the prioritization of patients with limited/without comorbidity for surgery to increase the ICU capacity—to the lowest group of agreement (61.1%–59.9%).

Analyzing the outcomes of Europe (n = 149, 44.2%), Asia (n = 115, 34.1%), and the Americas (ie, North and South America) (n = 71, 21.1%) separately demonstrated some changes in agreement. The European respondents did not reach consensus on statement 3 (76.5% agreement) regarding the prioritization of patients based on objective prognostic factors and comorbidity. In contrast to the overall outcomes, Asia achieved consensus on statement 4 (81.7% agreement) to prioritize each patient for pancreatic surgery, based on prognostic factors. Whereas Europe agreed on the importance of high-volume centers to operate high-risk patients during the COVID-19 pandemic (87.9% agreement), both Asia (75.7% agreement) and the Americas (76.1% agreement) did not reach consensus on statement 16. The recommendation for preoperative screening on COVID-19 (statement 19) reached solely consensus (84.5% agreement) in the Americas. See Table—Supplemental Digital Content 2–4, for the statement outcomes of Europe, Asia, and the Americas separately.

DISCUSSION

This global survey study aimed to clarify the role of pancreatic surgery during the COVID-19 pandemic through 21 statements. The statements regarding patient selection for the oncological and surgical treatment of pancreatic diseases could assist clinicians in their clinical decision-making and create a starting point for further discussion.

A literature review was performed (see Table—Supplemental Digital Content 5, for the search strategy) to evaluate the current evidence about pancreatic surgery during the COVID-19 pandemic. Kutikov et al6 concluded that (suspected) pancreatic cancer does not allow any treatment delay and, therefore, requires immediate surgical treatment, but did not address (neo)adjuvant therapy. Patients with both COVID-19 and cancer or treated with chemotherapy/surgery in the last months seem to be at risk for severe events (ie, ICU admission requiring invasive ventilation, or death) in comparison to COVID-19 patients without cancer, according to a Chinese series.4 Therefore, Liang et al4 advised to postpone adjuvant chemotherapy or elective surgery for stable cancer in endemic areas. In contrast, Ueda et al7 emphasized that adjuvant therapy with curative intent for solid tumors should proceed, and surgery needs prioritization as well. This latter statement is supported by the Society of Surgical Oncology (SSO), stating that hepato-pancreato-biliary malignancies are typically aggressive and, therefore, should not be considered as “elective” care.11 In addition, the Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons (SAGES) and the European Association of Endoscopic Surgery recommended to postpone all elective surgery with exception of surgical care for life threatening diseases such as progressive malignancies.12 Nevertheless, the limited evidence regarding the role of pancreatic surgery in the era of the COVID-19 pandemic underlines the need for an international survey with clear statements, aiming to guide clinicians in their clinical decision-making. The statement outcomes of the present international expert survey revealed several consensus statements as well as statements that need further discussion.

Triage

Patients with increased risk for postoperative respiratory failure should not be prioritized for surgery in absence of full hospital capacity, according to consensus statement 6. In contrast, only 61% agreement was reached on statement 5 comprising the proposition for surgery only for patients with limited/without comorbidity to minimize the use of ICU capacity for COVID-19 patients. The American College of Surgeons (ACS) underlined consensus statement 6, stating that “For elective cases with a high likelihood of postoperative ICU or respirator utilization, it will be more imperative that the risk of delay to the individual patient is balanced against the imminent availability of these resources for patients with COVID-19.”13 The aggressive biology of pancreatic cancer justifies elective pancreatic surgery as indispensable care12 and, therefore, should not be exclusively performed for very low risk patients as prevention to overload hospital resources (see the section “Pancreatic cancer” below for further explanation and recommendations). This could be the rationale for a low agreement on statement 5. The ACS emphasized that continuation of “elective” surgical care has to be frequently evaluated and adapted if needed, based on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on local resources.13 A reliable and objective model is needed to stratify patients and guide prioritization in accordance to hospital capabilities, such as the recently developed respiratory failure risk score for elective abdominal and vascular surgery, that identified pancreatic surgery among others as an independent risk factor for postoperative respiratory failure.14

Screening and Protection for COVID-19

Before pancreatic surgery, most centers represented in this survey screened their patients for symptoms of COVID-19. No consensus was reached to recommend COVID-19 preoperative testing/screening (statement 19). This seems a plea to obligate some type of screening, but not necessarily with PCR and/or computed tomography chest, particularly considering SAGES. SAGES underlines the recommendation of the Corona Virus Global Surgical Collaborative to perform some type of screening test for all patients (even if asymptomatic and without risk factors) who will undergo a surgical or interventional endoscopic procedure in institutions seeing high volumes of COVID-19 patients.12 In addition, ACS advised to wait for the results of COVID-19 testing in patients who may be infected.13

Based on consensus, patients who will undergo pancreatic surgery should be informed about the following additional risks: COVID-19 infection during hospitalization, possible nonoptimal postoperative management (ie, shortage of ICU beds), increased risk of COVID-19 related mortality due to surgery or the cancer condition (statement 17). Furthermore, this survey convincingly recommends that operating room (OR) personnel have to wear adequate protective features during surgery, considering their increased risk for COVID-19 infection during surgical procedures (statement 20).15,16

Pancreatic Cancer

According to the consensus statements for patients with pancreatic cancer, each patient should be operated after completing neoadjuvant therapy (statement 1), as is also advised by the SSO.11 However, patients should be prioritized based on objective prognostic factors and comorbidities in case of limited resources. If surgery is postponed, patients should continue with neoadjuvant therapy (statement 3), but neoadjuvant therapy should not be used to select each patient with nonmetastatic pancreatic cancer for surgery (statement 2). Subsequently, patients with postponed surgery need to be evaluated as soon as possible for surgery when resources are available again (statement 7). Oba et al17 recently described the value of a new nomogram for pancreatic cancer, estimating patients’ predicted survival based on preoperative factors and confirmed the prognostic power of known predictive factors. These models could be used for prioritization of surgery for pancreatic cancer in case of limited resources. However, no consensus was reached on statement 4 and 5 to prioritize each pancreatic cancer patient on comorbidity and objective pancreas cancer-related prognostic factors, considering the life threatening nature of pancreatic cancer. Nevertheless, statement 18—prioritization of COVID-19 patients with a better prognosis over pancreatic cancer patients adhering to the process of triage for hospital resources and ICU beds—did not reach 60% agreement. However, the difficulty to prioritize between patients with severe COVID-19 or resectable pancreatic cancer is conceivable. See the section “Triage” for further explanation and recommendations.

Italy has demonstrated the feasibility of continuing crucial cancer care during the COVID-19 pandemic, among others by appropriate resource allocation and separate health care pathways between COVID-19 patients and noninfected cancer patients, structured by performance criteria (eg, hospital volume).3,18

Periampullary Malignancies (Without Pancreatic Cancer)

Statement 8 proposed to manage distal bile duct cancer as equivalent to pancreatic cancer. However, the lack of consensus (71%) implies that surgery might have slightly less priority in comparison to pancreatic cancer since 23% of respondents disagreed on the other hand. The SSO stated that extrahepatic bile duct cancer and ampullary and duodenal adenocarcinomas should be operated as soon as feasible, regardless of the presence of symptoms.11 However, a high disagreement rate (40%) was reached on statement 15 for postponing surgery or giving neoadjuvant chemotherapy for duodenal and ampullary cancers in absence of life threatening risks (ie, bleeding, bowel obstruction). Since evidence is limited about the efficacy of neoadjuvant chemotherapy for these cancers so far and could not be deemed to stable diseases,11 many physicians might thought these should be resected as indicated.

Benign or Premalignant Pancreatic Diseases

Consensus was reached to postpone surgery for benign and premalignant pancreatic diseases, including IPMNs, pNETs, chronic pancreatitis, and infected pancreatic necrosis. Exceptions comprise life threatening complications of chronic pancreatitis or infected pancreatic necrosis, symptomatic pNETs without effective alternative treatment options, or pNETs or IPMNs with suspicion for malignancy (statements 9–14).

High-Volume Care

Volume–outcome relationships in pancreatic surgery are well established with shorter hospital stay and lower mortality in high-volume centers.10,19,20 Pancreatic surgery in high-risk patients should not be performed in low-volume centers during the COVID-19 pandemic, aiming to reduce the risk of long hospital stay and major complications requiring ICU care (statement 16). Remarkably, the sensitivity analysis revealed that only Europe reached consensus in contrast to Asia and the Americas.

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Statement 21 demonstrated the limited evidence regarding the safety of minimally invasive surgery, illustrated by the substantial percentage of respondents who agreed (65%) or were uncertain (24%). Although previous research has shown that laparoscopy can lead to aerosolization of blood borne viruses,21,16,15 SAGES advised to continue to perform minimally invasive surgery in accordance to their risk reducing procedural advice. SAGES will monitor emerging evidence considering the limited evidence about the relative risk of COVID-19 spreading in the OR by minimally invasive surgery in comparison to conventional open surgery.12 The ACS mentioned that aerosol-generating procedures increase the risk for OR personnel and may not be avoidable, but confirmed the insufficiency of evidence to recommend or discommend minimally invasive surgery.13 Meanwhile, SAGES underlined the proven benefits of minimally invasive surgery to reduce postoperative morbidity and hospital stay and, therefore, should be strongly considered in these patients.

Strengths and Limitations

The strength of this survey is the global range of respondents, representing a wide range of countries and continents. However, the results should be interpreted in light of some limitations. First, only 10.4% nonsurgeons (eg, medical oncologists and gastroenterologists) participated in this survey, which could possibly outbalance the discussion regarding the oncological treatment of pancreatic diseases. Second, a relatively small group of 8 countries was responsible for the majority of survey participants (76.6%). Third, only a minority of participants represented the nonacademic centers.

CONCLUSIONS

In summary, this survey reached consensus on the majority of statements for the role of pancreatic surgery during the COVID-19 pandemic to optimize safety for patients and clinicians and safeguard health care capacity by prioritizing only the most relevant care for patients with non-COVID-19 pancreatic diseases.

The statements maybe be updated, based on more solid evidence about the management of periampullary cancers (ie distal bile duct cancer, and duodenal and ampullary adenocarcinomas), preoperative screening modalities, and the safety of minimally invasive surgery in relation to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank all participating members and the leadership of the Pancreas Club, European Pancreatic Club, Chinese Pancreatic Surgery Association, European Consortium on Minimally Invasive Pancreatic Surgery, Study Group of Preoperative Therapy for Pancreatic Cancer, Study Group of Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma with Peritoneal Metastasis, and International Study Group on Cystic Tumors of the Pancreas for supporting this survey.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

S.S, C.L.W., M.A.H., M.G.B., and M.D.C. are shared supervisors.

A.O. and T.F.S. contributed equally to this study.

Authors’ contributions: A.O., T.F.S., S.S., C.L.W., M.A.H., M.G.B., and M.D.C. contributed to the conception and designed the study; A.O., T.F.S., M.H.A., M.G.B., and M.D.C. managed the project; A.O., T.F.S., M.L., T.H., N.Z., W.H.N., M.U., R.D.S., W.W., Y.Z., S.S., C.L.W., M.A.H., M.G.B., and M.D.C. contributed to the acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data; A.O., T.F.S., M.G.B., and M.D.C. participated in drafting the article; M.L., T.H., N.Z., W.H.N., M.U., R.D.S., M.H.A., W.W., Y.Z., S.S., C.L.W., and M.A.H. participated in revising the article critically for important intellectual content; all authors gave final approval of the final manuscript for submission.

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1. World Health Organization (WHO). Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): situation report, 51. 2020. Available at: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/331475/nCoVsitrep11Mar2020-eng.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y. Accessed on: March 28, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grasselli G, Pesenti A, Cecconi M. Critical care utilization for the COVID-19 outbreak in Lombardy, Italy: early experience and forecast during an emergency response. JAMA 2020; doi:10.1001/jama.2020.4031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pellino G, Spinelli A. How COVID-19 outbreak is impacting colorectal cancer patients in italy: a long shadow beyond infection. Dis Colon Rectum 2020; doi:10.1097/DCR. 0000000000001685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liang W, Guan W, Chen R, et al. Cancer patients in SARS-CoV-2 infection: a nationwide analysis in China. Lancet Oncol 2020; 21:335–337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang H, Zhang L. Risk of COVID-19 for patients with cancer. Lancet Oncol 2020; 21:e181.doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30149-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kutikov A, Weinberg DS, Edelman MJ, Horwitz EM, Uzzo RG, Fisher RI. A War on Two Fronts: Cancer Care in the Time of COVID-19. Annals of Internal Medicine 2020. Available at: https://annals.org/aim/fullarticle/2764022/war-two-fronts-cancer-care-time-covid19?fbclid=IwAR2ouycwL74nYSPEIQTs2DALPQ73ZK3FWTnQh21FkBZOpjef18gldMYXSw4. Accessed on: March 28, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ueda M, Martins R, Hendrie PC, et al. Managing cancer care during the COVID-19 pandemic: agility and collaboration toward a common goal. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2020. 1–4. doi:10.6004/jnccn.2020.7560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bosman FT, Carneiro F, Hruban RH, et al. WHO Classification of Tumors of the Digestive System (4th edition). Lyon: IARC Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tanaka M, Fernandez-del Castillo C, Adsay V, et al. International consensus guidelines 2012 for the management of IPMN and MCN of the pancreas. Pancreatology 2012; 12:183–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hata T, Motoi F, Ishida M, et al. Effect of hospital volume on surgical outcomes after pancreaticoduodenectomy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Surg 2016; 263:664–672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Society of Surgical Oncology (SSO). Resource for Management Options of GI and HPB Cancers. 2020. Available at: https://www.surgonc.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/GI-and-HPB-Resource-during-COVID-19-4.6.20.pdf. Accessed on: April 6, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons (SAGES). SAGES and EAES recommendations regarding surgical response to COVID-19 crisis. Available at: https://www.sages.org/recommendations-surgical-response-covid-19/ Accessed on: April 11, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 13. American College of Surgeons (ACS). COVID-19: Elective Case Triage Guidelines for Surgical Care 2020. Available at: https://www.facs.org/covid-19/clinical-guidance/elective-case. Accessed at: April 5, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johnson AP, Altmark RE, Weinstein MS, et al. Predicting the risk of postoperative respiratory failure in elective abdominal and vascular operations using the National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (NSQIP) Participant Use Data File. Ann Surg 2017; 266:968–974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Choi SH, Kwon TG, Chung SK, et al. Surgical smoke may be a biohazard to surgeons performing laparoscopic surgery. Surg Endosc 2014; 28:2374–2380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kwak HD, Kim SH, Seo YS, et al. Detecting hepatitis B virus in surgical smoke emitted during laparoscopic surgery. Occup Environ Med 2016; 73:857–863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oba A, Croce C, Hosokawa P, et al. Prognosis based definition of resectability in pancreatic cancer: a road map to new guidelines. Ann Surg 2020; doi:10.1097/SLA.0000000000003859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Curigliano G. The Treatment of Patients With Cancer and Containment of COVID-19: Experiences From Italy. ASCO Daily News 2020. Available at: https://dailynews.ascopubs.org/do/10.1200/ADN.20.200068/full/. Accessed on: March 28, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 19.van der Geest LGM, van Rijssen LB, Molenaar IQ, et al. Volume–outcome relationships in pancreatoduodenectomy for cancer. HPB (Oxford) 2016; 18:317–324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.van Rijssen LB, Zwart MJ, van Dieren S, et al. Variation in hospital mortality after pancreatoduodenectomy is related to failure to rescue rather than major complications: a nationwide audit. HPB (Oxford) 2018; 20:759–767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alp E, Bijl D, Bleichrodt RP, et al. Surgical smoke and infection control. J Hosp Infect 2006; 62:1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zheng MH, Boni L, Fingerhut A. Minimally invasive surgery and the Novel Coronavirus outbreak: lessons learned in China and Italy. Ann Surg 2020; doi:10.1097/SLA.0000000000003924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.