Abstract

Purpose of review:

Opioid use disorder (OUD) is a global phenomenon and is on the rise in Africa, denoting a shift from historical patterns of drug transport to internal consumption. In contrast, opioids for clinical pain management in Africa remain among the least available globally. This region also has the highest HIV and HCV disease burden, and the greatest shortages of health workers and addiction treatment. We undertook a systematic review of the literature to describe opioid use in Africa and how it is being addressed.

Recent findings:

A total of 84 articles from 2000 to 2018 were identified. Descriptions of country-specific populations and patterns of opioid misuse were common. A smaller number of articles described interventions to address OUD.

Summary:

OUD occurs in sub-Saharan Africa, with attendant clinical and social costs. Evidence-based policies and health system resources are needed to promote OUD prevention and management, and infectious disease transmission reduction.

Keywords: Addiction, opioid use disorder, Africa, HIV, HCV, opioid agonist treatment, people who inject drugs, health workforce

Introduction

Opioids can be consumed as part of a clinically indicated pain regimen or non-clinically as part of the growing global problem of opioid use disorder (OUD). Opioid consumption has occurred disproportionately in high-income countries, with low income countries representing 6% of global opioid consumption [1]. As opioid trafficking routes have changed globally to increasingly utilize African trading routes, opioid consumption for non-clinical indications has increased in this region. While consumption often started among people who smoke cannabis [2] in areas proximate to where opioids were imported (e.g., ports), this growing opioid use has touched workers, farmers, youth, and others, in rural as well as urban settings. The original push of opioids into the African market was to smuggle opioids to higher paying markets, namely Europe. This has been highly successful; 87% of the world’s illicit seizures of pharmaceutical opioids are in Africa [3]. This availability created opportunities for local sales and, as a result, a burgeoning opioid market in sub-Sahara Africa, facilitated by more transport infrastructure (as opposed to having to transverse high mountains in Central Asia) and the promise of wealth [4].

Evidence-based medications exists for opioid use disorder, known as medication for opioid use disorder (MOUD), that can reduce overdose, HIV and hepatitis C virus (HCV) transmission risk. Opioid antagonists such as naloxone can be administered in the community for acute overdose reversal. Evidence-based interventions to reduce the acquisition of blood borne pathogens also exist, including needle and syringe programs (NSPs). Unfortunately, these programs to address opioid misuse, and substance use in general, are in limited supply in Africa [5]. Likewise, availability of mental health and addiction health professionals is under resourced [6] compared with high-income settings (14.63 per 100,000 in the United Kingdom vs. 0.01 psychiatrist per 100,000 in Tanzania [7]).

Further complicating the problem of OUD in this region of the world is the fact that Africa has the highest burden of HIV, and tuberculosis (TB) globally [8, 9]. Some estimates place the African continent at the highest HCV prevalence (5.3%) among all regions worldwide [10], while other models put the HCV prevalence in African regions lower [11]. The ongoing opioid epidemic in Africa, combined with infectious disease transmission acceleration and the low availability of resources to address these issues, may prevent further progress towards ambitious goals such as the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) 90–90-90 targets (i.e., 90% of all people with HIV know their status, 90% of those who are HIV-positive on treatment, and 90% of those on treatment achieving viral suppression) to reduce HIV transmission and improve care and treatment of people living with HIV globally [12]. We undertook a literature review to document the extent of the opioid epidemic in Africa, its management, resulting intervention needs, and to generate future recommendations.

Methods

We reviewed the English-language literature from 1 January 2000 to 22 June 2018 in PubMed, CINAHL, SCOPUS, and Google Scholar. We chose to extend the timeframe of the search beyond the most recent five years of publications, given the relative dearth of articles. Search terms that were used included: Africa / Kenya / Tanzania AND opioid use / addiction, medication assisted treatment/methadone assisted treatment, substance use/abuse, heroin, needle syringe exchange, buprenorphine, naltrexone, naloxone, IV/injection drug users, injecting drug, people who inject drugs, and drug use/abuse/addiction. All search terms were used in all databases, except for Google Scholar which yielded limited new results.

We excluded titles that dealt with opioids in palliative care, or therapeutic opioid use for pain management; studies of substance use in Africa that were not opioid-specific, and studies focused only on epidemiologic estimations methodology as they were not opioid specific. Finally, we excluded multinational surveys and systematic reviews, in favor of original research publications. We also reviewed bibliographies of recent articles (2017–2018) to ensure capture of all recent literature.

Findings

We identified 84 articles describing original research related to substance use disorders, including OUD, in Africa. Table 1 summarizes key elements of the recent literature of the last 18 years (2000–2018). Most of the studies are observational, with only a handful of treatment trials or interventions described; and almost no implementation science framing or work. Additionally, it is important to point out the lack of available epidemiologic or clinical data about opioid overdose in the literature examined; there is practically no information known about overdose mortality rates in Africa.

Table 1.

Overview of opioid access, use and problems in African jurisdictions

| Study | Author/Year | Design | Sample | Outcomes/Conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| “They accept me, because I was one of them”: formative qualitative research supporting the feasibility of peer-led outreach for people who use drugs in Dakar, Senegal. | 2018/Stengel et al. [13] | Semi-structured qualitative interviews | 44 interviews with people who use drugs, peer educators and service providers | Peer-led outreach initiatives play a role in harm reduction activities among people who use drugs. Peer educators in this study were predominantly older men; should be more diversified to reflect the spectrum of people who use drugs, i.e., younger people and women. Broader structural and system changes need to occur in order for peer-led outreach to achieve the potential to play a central role in harm reduction interventions. |

| Context and characteristics of illicit drug use in coastal and interior Tanzania | 2018/Tiberio et al. [4]• | Rapid assessment, triangulating in-depth interviews of key informants, secondary informants, and ethnographic mapping | 436 interviews across 47 towns/municipalities in 12 regions of Tanzania. Three fourths of people who use drugs, primarily male, one fourth secondary informants, such as police officers or health-care workers | Illicit drug use increasing in all regions. Most people who use drugs work in the cash economy. Cannabis most common drug, then heroin. Women using drugs increasing, though less visible. |

| The becoming of methadone in Kenya: How an intervention’s implementation constitutes recovery potential | 2018/Rhodes et al. [14] | Qualitative interviews | 30 interviews with individuals undergoing methadone treatment in Nairobi, Kenya | Methadone is an object of recovery potential, which produces an affective flow through social interactions. |

| Human immunodeficiency virus infection predictors and genetic diversity of hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virus co-infections among drug users in three major Kenyan cities | 2018/Oyaro et al. [15]• | Cross-sectional study using Respondent-Driven Sampling (RDS) | 673 drug users from Nairobi, Mombasa, and Kisumu, in Kenya. 93% male | HBV, HCV, and HIV prevalence among drug users was 4.3, 6.5, and 11.1% respectively, with evidence of coinfections. HCV genotypes were 1a (72%) and 4a (22%). With high levels of genetic diversity, harm reduction strategies and monitoring for effective patient management should be implemented. |

| Substance abuse treatment engagement, completion and short-term outcomes in the Western Cape province, South Africa: Findings from the Service Quality Measures Initiative | 2018/Myers et al. [16] | Multivariate logistic regression | Facilities in Western Cape Province of South Africa implementing a substance use disorder (SUD) performance system. Includes data from 1094 adult patients | 59% of patients completed treatment, which is associated with greater likelihood of abstinence at completion. Improving rates of treatment completion will enhance SUD treatment effectiveness in South Africa. |

| Who has ever loved a drug addict? It is a lie. They think a ‘teja’ is a bad person: multiple stigmas faced by women who inject drugs in coastal Kenya | 2018/Mburu et al. [17]• | Qualitative interviews and focus groups | 45 women who inject drugs in Mombasa and Kilifi, Kenya, and 5 key stakeholders | Women who inject drugs experience multiple stigmas. HIV and harm reduction programs should address these different forms of stigma, which requires a combination of interventions. |

| Socio-demographic and sexual practices associated with HIV infection in Kenyan injection and non-injection drug users | 2018/Budambula et al. [18] | Cross-sectional descriptive study using RDS | 451 HIV-infected and uninfected injection drug users, non-injection drug users, and non-drug-users in Mombasa city, Coastal Kenya | Predictors of HIV infection include sex for police protection and history of sexually transmitted infections in people who inject drugs, and divorced, separated, or widowed marital status in those who do not inject. This suggests targeted, preventive measures for people who use drugs. |

| Perspectives on biomedical HIV prevention options among women who inject drugs in Kenya. | 2018/Bazzi et al. [19] | Qualitative interviews | 9 HIV-uninfected women who inject drugs in Kisumu, Kenya | Among the 3 biomedical HIV prevention methods that were tested or under development at the time (antiretroviral oral pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), intravaginal rings, and topical microbicide gels), only 1 woman had ever heard of PrEP, and 1 of microbicides gels. But all would be interested in trying at least 1 method, with most interested in microbicide gels (n = 7), followed by intravaginal rings (n = 6) and oral PrEP (n = 5). |

| Barriers and facilitators of access to HIV, harm reduction and sexual and reproductive health services by women who inject drugs: role of community-based outreach and drop-in centers | 2018/Ayon et al. [20]• | Qualitative interviews and focus groups | 45 women who inject drugs in Mombasa and Kilifi, Kenya, and 5 key stakeholders | Community-based services such as outreach or drop-in centers mitigate barriers to women’s access to health services. They increase women’s access to harm-reduction interventions, and demonstrate the need to strengthen community-based programming |

| “Codeine is my helper”: misuse of and dependence on codeine-containing medicines in South Africa | 2017/Van Hout et al. [21] | In-depth interviews conducted and analyzed using empirical phenomenological psychological 5-step method | 25 adults with codeine users and dependence recruited from addiction treatment centers in South Africa | Primary themes included: participant profile and product preferences, motives for codeine use, transitioning from use to dependence, purchasing from pharmacy, alternative sourcing, codeine effect and withdrawal experiences, help-seeking and treatment, and strategies for prevention. Results demonstrate the importance of countering codeine misuse and dependence. |

| Hepatitis C: a South African literature review and results from a burden of disease study among a cohort of drug-using men who have sex with men in Cape Town, South Africa. | 2017/ Semugoma et al. [22] | Descriptive study to describe HCV burden among drug users. Blood samples for anti-HCV antibody, HBV surface antigen and surface antibody testing. HIV status extracted from case notes. Drug and sexual risk behavior captured with survey. | 41 adult men who have sex with men (MSM) accessing harm reduction services at the Anova Health Institute’s Health4Men clinic in Cape Town, SA. 5% transgender women. | High burden of HCV exposure or infection. 11 (27.0%) were anti-HCV antibody-positive; 10/11 (91.0%) were positive for HBV surface antibodies; and 1 (2.0%) screened positive for HBV. Of the HCV-seropositive individuals, HIV status was known in 8/11; 3/8 (37.5%) were HIV-positive. MSM (especially those who report drug use) should be actively screened for HCV, and referral networks developed for treatment access. |

| Codeine misuse and dependence in South Africa: Perspectives of addiction treatment providers | 2017/Parry et al. [23] | Cross-sectional semi-structured interview on provider experience of clients analyzed using descriptive statistics and thematic analysis for qualitative and quantitative data | 15 addiction treatment providers from 11 treatment centers in South Africa with high numbers of patients in treatment for codeine-related problems, and 5 members of executive committee of South African Addiction Medicine Society. | Only 2/20 trained in codeine-dependence management. Treatment included psychosocial interventions, detoxifications, and pharmacotherapy. Most common profession was social work, and then psychiatry. Participants stressed need for more training on codeine misuse/dependence and identified patient barriers to entering treatment. |

| Reducing substance use and risky sexual behaviour among drug users in Durban, South Africa: Assessing the impact of community-level risk-reduction interventions | 2017/Parry et al. [24] | Quantitative analysis at baseline and post-agency implemented behavioral intervention and harm reduction strategies. | 138 non-injection drug users in Durban, South Africa | No decrease in drug use practices, though reduction in alcohol use. Demonstrates possibility of providing HIV risk-reduction services to a population of individuals who use substances. |

| Rural realities in service provision for substance abuse: a qualitative study in uMkhanyakude district, KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa | 2017/Mpanza et al. [25]• | Qualitative interviews and focus groups | 29 service providers in rural district of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa | Mental health service delivery in this rural area is challenging; a district, provincial, and national standard for substance use treatment services is needed, as well as response to the gaps in such under-resourced areas. |

| Prevalence and predictors of human immunodeficiency virus and selected sexually transmitted infections among people who inject drugs in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania: a new focus to get to zero | 2017/Mmbaga [26] | Cross-sectional study using RDS | 620 persons in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, 94% men | People who inject drugs in Dar es Salaam carry an HIV burden 3 times higher than the overall Tanzanian population. Behavioral and biological risk factors must be addressed to reduce HIV incidence. |

| Report on the first government-funded opioid substitution programme for heroin users in the Western Cape Province, South Africa | 2017/Michie et al. [27]• | Naturalistic retrospective study reviewing records between standard care only and opioid agonist treatment (OAT) group | 135 participants in rehabilitation center in Cape Town in 2014 receiving standard care (n = 68) or OAT (n = 67) with naloxone for treatment of drug addiction | More participants in the OAT group (65.7%) than controls (44.1%) completed treatment. The OAT group had increased retention rates, increased response to treatment, but low abstinence from illicit opiates. Future programs should consider extending treatment duration. |

| Beyond methamphetamine: documenting the implementation of the Matrix model of substance use treatment for opioid users in a South African setting | 2017/Magidson et al. [28] | Comparison via chart review of people with primary opioid and primary methamphetamine use undergoing treatment at Matrix model substance use treatment site. Descriptive statistics and multivariable logistic regression | Patients who abused primarily opioids (N = 534) or methamphetamine (N = 1863) who had a screening visit at the first certified Matrix site in sub-Saharan Africa, located outside Cape Town, South Africa between June 2009 – May 2014 | Individuals who use methamphetamine were 50% more likely to initiate treatment and 4.5 times more likely to attend 4 treatment sessions than those who used opioids, and much more likely to engage in treatment. However, abstinence by treatment exit were equal between both groups, and barriers to treatment engagement for those with opioid use are unclear. |

| Prevalence and predictors of HCV among a cohort of opioid treatment patients in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania | 2017/Lambdin et al. [29]• | Multivariable Poisson regression with hepatitis C virus (HCV) serostatus as variable of interest based on review of programmatic data | 630 individuals enrolled in opioid treatment program/methadone clinic (OTP) at Muhimbili National Hospital in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Median age was 32 years, and 7% were women | 57% seroprevalence of HCV in study population, and 81% among individuals who were HIV positive. Data suggests high prevalence of HCV among OTP patients, related to use of heroin, sharing needles, HIV, and history of arrest. This is important in considering HCV care and treatment delivery for PWID. |

| HIV and hepatitis B and C co-infection among people who inject drugs in Zanzibar | 2017/Khatib et al. [30] | Cross-sectional survey using RDS | 408 individual who inject drugs in Zanzibar | Prevalence of hepatitis B surface antigenemia, HCV, and HIV infection were 5.9, 25.4, and 11.3%, respectively. Older age and longer duration of injection drug use were independently associated with HCV infection. HCV infection among people who inject drugs is lower in Zanzibar than in other countries but could rise without proper interventions. |

| Convenience without disclosure: a formative research study of a proposed integrated methadone and antiretroviral therapy service delivery model in Dar es Salaam Tanzania | 2017/Cooke et al. [31] | In-depth semi-structured interviews with providers and HIV-positive patients to examine patient and provider perspectives; thematic content analysis | 12 OTP clinic providers and 20 OTP patients (10 women and 10 men, 10 on ART and 10 not on ART) at the Muhimbili National Hospital in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. | Themes included: Need for in-house point of care CD4 testing, in-house HIV clinical management, ART delivery through the OTP clinic, and electronic health information system. Integrating HIV care into the OTP clinic setting will reduce stigma and discrimination but must also maintain confidentiality about HIV status and not overburden providers. |

| First report of gender-based violence as a deterrent to methadone access among females who use heroin in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania | 2017/Balaji et al. [32]• | Case control study to examine factors associated with non-enrollment in methadone treatment; logistic regression and multivariable statistical analysis | Females who use drugs identified by snowball sampling in neighborhoods in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Sample included 202 women not enrolled in methadone as controls and 93 women enrolled in methadone as cases. | Violence and discrimination are significant barriers to methadone treatment for females, as intimate partner violence (IPV) was associated with not enrolling in methadone. Women enrolled in OAT had a higher proportion of risky sexual behaviors. It is important to develop and implement interventions targeted towards reducing gender-based violence to facilitate participation in methadone. |

| Generating trust: programmatic strategies to reach women who inject drugs with harm reduction services in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania | 2016/Zamudio-Haas et al. [33] | In-depth interviews with patients and their providers at MOUD clinic, to understand women’s enrollment experiences and retention in care based on gender inequities in drug treatment. Data thematically analyzed. | Men (n=6) and women (n=13) enrolled in MOUD program at Muhimbili National Hospital in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, and their service providers (n=6). | Results showed mistrust and discrimination against PWID, especially women who inject drugs. Trust is especially fundamental for recruiting women who inject drugs, and street-based outreach targeted to women who inject drugs can be especially helpful in increasing women’s participation in MOUD. |

| Improvements in health-related quality of life among methadone maintenance clients in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania | 2016/Ubuguyu et al. [34] | Routine data on clients enrolling in methadone focusing on changes in physical and mental health composite scores. Student t tests and backward stepwise regression analysis | 288 clients of the 419 clients enrolled in methadone program at Muhimbilli National Hospital in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, from February 2011 – April 2012. | Significant improvements noted in physical and mental health composite scores. Methadone treatment has positive short-term effects on health-related quality of life. |

| An ethnographic exploration of drug markets in Kisumu, Kenya | 2016/Syvertsen et al. [35] | Ethnographic fieldwork, surveys, and qualitative interviews | Surveys conducted with 151 injecting drug users in Kisumu, Kenya, 29 participants in qualitative interviews | Drug availability is increasingly important, and there are widespread perceptions of cocaine availability and injection. Expanded drug surveillance, education, and programming responsive to local conditions is important. |

| HIV prevalence and risk among people who inject drugs in 5 South African cities | 2016/Scheibe et al. [36] | Cross-sectional survey | 450 people who inject drugs from five south African cities | 26% of females and 13% males always share injecting equipment, while 49% of participants use contaminated injection equipment the last time the injected. There is a need for increased access to sterile injecting equipment, education around safer injecting practices, and access to sexual and reproductive health services for people who inject drugs. |

| Consider our plight: A cry for help from nyaope users | 2016/Mokwena et al. [37] | Qualitative interviews and focus groups | 108 participants in 9 focus group discussions and 20 in depth interviews who were Nyaope users in South Africa | This exploratory study demonstrates that the drug is very strong, easy to access, and difficult to quit. Users express a desire to find help to overcome current circumstances |

| Correlates of health care seeking behaviour among people who inject drugs in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania | 2016/Mlunde et al. [38] | Baseline cross-sectional study as part of prospective cohort study involving PWID with aim of examining role of integrated MOUD program on reducing high-risk injecting, sexual behaviours, and criminal activities, while increasing access to care. | MOUD program enrollees (n = 273) and community-recruited PWID (n = 305) as controls in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania at Muhimbili National Hospital and Mwananyamala Hospital. | PWID have poor access to health care, and the majority of participants do not seek health care. Interventions targeting PWID must be implemented to improve their health-seeking behavior; this should include providing health education and increasing ability to generate income. |

| A mismatch between high-risk behaviors and screening of infectious diseases among people who inject drugs in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania | 2016/Mlunde et al. [39] | Baseline cross-sectional study as part of prospective cohort study | MOUD program enrollees (n = 273) and community-recruited PWID (n = 305) in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania at Muhimbili National Hospital and Mwananyamala Hospital. | Only 36% had been screened for HIV, 18.5% for tuberculosis, 11.8% of any STI, and 11.6% for hepatitis B/C. PWID practice high-risk behaviors but have poor utilization of screening services. |

| Heroin shortage in Coastal Kenya: A rapid assessment and qualitative analysis of heroin users’ experiences | 2016/Mital et al. [40]• | Qualitative interviews and focus groups | 66 key informant interviews and 15 focus groups among people who use heroin in Coast Province, Kenya | Themes involved desperation and uncertainty, with sub-themes of withdrawal, unpredictable drug availability, changes in drug use patterns, modifications in relationship dynamics among people who use drugs, family and community response, and new challenges with the heroin market resurgence. There was increased risk of morbidity, mortality, and disenfranchisement at social and structural levels. |

| Access to HIV treatment and care for people who inject drugs in Kenya: a short report | 2016/Guise et al. [41] | Qualitative longitudinal study | 44 PWID living with HIV in combination with other interviews with PWID, care providers, and community observation in Nairobi, Malindi, and Ukunda in Kenya. | Themes include: the hardship of addiction, silencing of HIV in the community, and discrimination and support in the clinic. These create barriers to care, and clinic-based care may be fundamentally difficult to access for some PWID. |

| Implementation of cognitive-behavioral substance abuse treatment in Sub-Saharan Africa: Treatment engagement and abstinence at treatment exit | 2016/Gouse et al. [42] | Retrospective chart review to assess treatment readiness and substance use severity at treatment entry as compared with treatment exit. | 2,223 clients screened at Matrix Model program outside Cape Town, South Africa. 66% were male, 86% unemployed, and the primary used substances were methamphetamine and heroin. | For 76% of the sample, this was the first time they had sought treatment for substance use. Rates of initiation and engagement with the Matrix substance use treatment model were comparable with substance use treatment in industrialized nations. Motivation was a key psychological factor that predicted treatment outcomes and engagement in treatment. |

| Opiate withdrawal syndrome in buprenorphine abusers admitted to a rehabilitation center in Tunisia | 2016/Derbel et al. [43] | Assessed buprenorphine withdrawal syndrome in subjects who sought treatment for dependence. | 30 male and 2 female patients who had completed 3 weeks of a 4-week treatment protocol at the only residential rehabilitation program in Tunisia. | Buprenorphine withdrawal in a detoxification regimen had a mild intensity and delayed onset and was more severe in females as compared to males, though the sample size was severely limited. |

| Prevalence and risk factors associated with HIV and tuberculosis in people who use drugs in Abidjan, Ivory Coast | 2016/Bouscaillou et al. [44] | RDS, using questionnaire, blood samples, and sputum samples | 450 heroin and/or cocaine users in Abidjan, Ivory Coast | PWUD in this area are at high risk of HIV, especially in women, sex workers, and men who have sexual relationships with other men. |

| Psychiatric comorbidity among Egyptian patients with opioid use disorders attributed to tramadol | 2016/Bassiony et al. [45] | Patients interviewed using a semi-structured questionnaire, addiction severity index, and a urine drug screening was performed to investigate psychiatric comorbidities associated with tramadol | 100 patients with opioid use disorders from tramadol and 100 control persons recruited from Zagazig University Hospital, Egypt. | Of the patients with Opioid Use Disorder due to tramadol, approximately three-fourths used other substances, one-third had drug-related problems, and they were twice as likely to have psychiatric and personality disorders. |

| HIV and STI prevalence and injection behaviors among people who inject drugs in Nairobi: results from a 2011 bio-behavioral study using respondent-driven sampling | 2015/Tun et al. [46]• | Cross-sectional study using RDS | 269 PWID in Nairobi, Kenya | PWID were predominantly male, 67.2% engaged in at least one risky injection practice per month, and HIV prevalence was 18.7%. HIV infection associated with being female, having injected drugs 5 or more years ago, and having practiced receptive syringe sharing. Harm reduction program must be implemented as HIV prevention in Kenya. |

| Linkage to care among methadone clients living with HIV in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania | 2015/Tran et al. [47]• | Examined linkage to care for HIV positive individuals by measuring days between HIV-positive test and CD4 result at methadone maintenance treatment clinic. Used multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression to examine factors associated with linkage to care. | 629 individuals receiving methadone treatment who tested positive for HIV after enrollment between February 2011, and January 2013, in Muhimbili National Hospital in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania | Stabilization through higher methadone doses, self-perceived poor health, and primary education or lower, increased probability of obtaining a CD4 count. Individuals with history of arrest were less likely to obtain a CD4 count and be linked to care. |

| Epidemiology of drug use and HIV-related risk behaviors among people who inject drugs in Mwanza, Tanzania | 2015/Tan et al. [48] | Used targeted sampling and participant referral to recruit and interview participants about their substance use and associated risk behaviors. Multivariate statistical analysis was used | 480 participants in Mwanza, Tanzania, recruited between June and August 2014. Sample was 92% male, had injected or used any kind of drug in the past 12 months. More than a tenth considered themselves homeless. | Unstable housing and cohabitation status were only characteristics significantly associated with heroin injection. More than half of heroin injections left syringes in common locations, and half reported sharing needles and syringes. Other risk behaviors such as no condom use during sex and use of drugs during sex was also reported. There was poor awareness of risks of needle/syringe sharing and drug use. |

| Evidence of injection drug use in Kisumu, Kenya: implications for HIV prevention | 2015/Syvertsen et al. [49]• | Quantitative data using descriptive statistics and logistic regression | 151 people who used drugs in Kisumu, Kenya | Woman had greater than 4 times higher likelihood of being HIV positive. STI symptoms and sharing needles or syringes were also associated with HIV positive status. |

| The efficacy of a blended motivational interviewing and problem-solving therapy intervention to reduce substance use among patients presenting for emergency services in South Africa: A randomized controlled trial | 2015/Sorsdahl et al. [50] | Randomized controlled trial enrolled patients presenting to one of three 24-hour emergency departments (EDs) who had risk for substance use using Alcohol, Smoking, and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST). Enrolled to following interventions: Motivational Interviewing (MI), blended MI and Problem-Solving Therapy (MI-PST), or a Pyscho-educational control group to examine reduction in ASSIST scores. | 335 patients presenting to ED in Cape Town, South Africa, ≥ 18 years, with moderate to high risk from substance use as measured by ASSIST | Though ASSIST scores decreased in all three arms, ASSIST scores at 3 months were significantly lower in the MI-PST group; this group also had decreased risk scores for depression at follow-up. The blended MI-PST intervention has promising outcomes for substance use and depression. |

| Navigating the poverty of heroin addiction treatment and recovery opportunity in Kenya: access work, self-care and rationed expectations | 2015/Rhodes et al. [51] | Qualitative interview analysis with field observation | 109 individuals with current experience of injecting drugs in Nairobi, Malindi, and Ukunda, in Kenya | In the drug treatment experience, rehab is used as a primary means of respite and harm reduction rather than recovery. It is important to diversify drug treatments and combine them with social interventions enabling their access. |

| Is the promise of methadone Kenya’s solution to managing HIV and addiction? A mixed-method mathematical modelling and qualitative study | 2015/Rhodes et al. [52]• | Combined mathematical modelling with qualitative data analysis to explore effects of implementing methadone in Kenya and project HIV transmission impact. Also drew on in-depth qualitative interviews and identified core thematic categories. | 109 in-depth qualitative interviews with PWID in Nairobi (n=30), Malindi on the North Coast (n=50), and Ukunda on the South Coast (n=29), focusing on lived experience of HIV risk and prevention, drug treatment and addiction recovery, and perception of methadone | The modelled impact of opioid agonist treatment shows slight reductions in HIV incidence over 5 years at coverage levels anticipated in planned roll-out, but there is higher impact with increased coverage. Qualitative findings show a culture of “rationed expectations” with little access to drug treatment and methadone as a symbol of hope. |

| Co-infection burden of hepatitis C virus and human immunodeficiency virus among injecting heroin users at the Kenyan coast | 2015/Mwatelah et al. [53] | Screening for HIV-1 and HCV infections by serology and polymerase chain reaction | 186 injecting heroin users in Malindi, Kenya. | HIV-1 prevalence was 87.5%, HCV prevalence was 16.4%, coinfection was 17.9% and 11.8% were uninfected. Mono and dual infections with HIV-1 and HCV are high among people who inject heroin but ART coverage is low |

| Drug use and sexual behavior: the multiple HIV vulnerabilities of men and women who inject drugs in Kumasi, Ghana | 2015/Messersmith et al. [54] | In-depth qualitative interviews coded and analyzed by theme | 30 (20 men and 10 women) PWID and 6 HIV program managers and health service providers in Kumasi, Ghana | More than half of participants shared needles/syringes (N/S), most shared a common mixing container, and all shared N/S with intimate partners. Some routinely use N/S found on ground or hospital dumpster. Most were sexually active and had more than 1 partner in the last 6 months, few reported condom use. Several had no knowledge of HIV transmission through injecting. |

| Addiction and treatment experiences among active methamphetamine users recruited from a township community in Cape Town, South Africa: A mixed-methods study | 2015/Meade et al. [55] | Structured clinical interviews, computerized surveys, and in-depth interviews to assess substance abuse and treatment history, drug-related risks, and experiences with methamphetamine use and drug treatment | Individuals with active methamphetamine use (201 men and 159 women) ranging in age form 18 – 66 years from Delft, near Cape Town, South Africa. Majority were “coloured”, unemployed, and had not completed high school. 30 participants completed individual in-depth interviews. | Participants had used methamphetamine for 7 years on average, and 23.5 of the past 30 days; 60% used daily. Majority met ICD-10 criteria for use disorder and had experienced severe consequences for their substance use. 90% wanted treatment. In qualitative analysis, barriers to treatment include beliefs that it is ineffective and relapse is inevitable, though they also expressed desire to be drug free and improve family functioning. |

| HIV prevalence and risk behaviors among people who inject drugs in two serial cross-sectional respondent-driven sampling surveys, Zanzibar 2007 and 2012 | 2015/Matiko et al. [56] | Behavior and biological surveillance using RDS | 499 and 408 PWID participants in 2007 and 2012 surveys respectively, predominantly male, in Zanzibar | Duration of injection drug use for 5 years or more was associated with higher odds of HIV infection. HIV prevalence and indicators of risk and preventive behavior among PWID were more favorable in 2012 than 2007; prevention programs for this population were also scaled up at this time. |

| Prevalence and behavioural risks for HIV and HCV infections in a population of drug users of K | 2015/Lepretre et al. [57]• | Capture-recapture estimated size of population using drugs. RDS used to recruit a sample of people who used drugs and determine HIV, HBV, and HCV status. Behavioral data and blood samples were gathered, and data was analyzed using the RDS analysis tool, and logistic regression. | 506 people with heroin and/or cocaine use living for at least 3 months in Dakar, Senegal who had injected any psychoactive substance in the past three months. Population predominantly male with mean age of 42.1 years and low educational level. N = 69 women with higher proportion of sexual relationships associated with prostitution, and higher proportion of precarious family situation. | Estimated 1324 as size of people who use drugs population in Dakar area. HIV, HCV, and HBV prevalence were 5.2%, 23.3%, and 7.9% respectively. Women more at risk for being HIV infected. PWID was risk factor for HCV and HIV infection, and older age and female sex were additional risk factors for HIV infections. Women need targeted interventions for decreasing HIV exposure. |

| HIV prevalence, estimated incidence, and risk behaviors among people who inject drugs in Kenya | 2015/Kurth et al. [58]• | Respondent-driven sampling for HIV-1 prevalence and viral load determination and survey data | 1785 PWID recruited from Nairobi or Coast regions in Kenya | Heroin was the most commonly injected drug in both regions, and receptive needle/syringe sharing at last injection was more common in Nairobi. The HIV epidemic is well-established among PWID in both Nairobi and Coast regions. |

| A qualitative analysis of transitions to heroin injection in Kenya: implications for HIV prevention and harm reduction | 2015/Guise et al. [59] | Qualitative study of HIV care access and ethnographic study of heroin trade in Kenya | 118 individuals, both PWID and community stakeholders, interviewed in the first study across Nairobi, Malindi, and Ukunda. 132 in-depth, semi structured interviews with 92 respondents acquired in the second study using ethnographic methods. | PWID link transitions to injecting to a range of social and behavioral factors, including the local drug supply and economy. Structural and social factors interact in the transition to injection; harm reduction programs must respond to these varied transitional experiences. |

| Adolescent tramadol use and abuse in Egypt | 2015/Bassiony et al. [60] | Cross-sectional study with systematic random sampling method. Students screened for tramadol use using Drug Use Disorders Identification Test and urine screen for Tramadol | 204 school students age 13–18 in 6 schools in Zagazig, Sharkia governorate, Egypt. Total target population was 86,567. 148 males, with mean age of 15.26 years. | Prevalence of tramadol use among school students was 8.8%. Significant associations between tramadol use and older age, male gender, higher education, and smoking. 2/3rd started with tramadol as first drug after smoking tobacco. Over 1/3rd of those who used tramadol had drug-related problems. |

| Evaluating the effect of HIV prevention strategies on uptake of HIV counselling and testing among male most-at-risk-populations in Nigeria; a cross-sectional analysis | 2015/Adebajo et al. [61] | Cross-sectional study. χ2 statistics used to test for differences in the distribution of categorical variables across groups; logistic regression used to measure effect of the different HIV counseling and testing (HCT) strategies. | MSM (≥15 years and engaged in anal sex in the past year) and PWID (≥15 years who had injected prescription and psychosocial drugs in the past year) prior to joining the Men’s Health Network, Nigeria HIV prevention program. A total of 1988, 14,726 and 14, 895 male most-at-risk populations (MARPs) were offered HCT by S1 (referral to male MARP friendly health facility for HCT), S2 (referral to mobile HCT teams) and S3 (peer delivery of HCT) strategies, respectively. | HCT uptake was 87%. Among the HCT strategies employed, peer delivery, had the greatest impact, more male MARPs reached, with more HIV-positives and new testers identified. However, all three strategies reached a large proportion of first time testers. |

| Clinical chemistry profiles in injection heroin users from Coastal Region, Kenya | 2014/Were et al. [62] | Cross sectional clinical laboratory study. Statistical analysis utilized chi-square tests, non-parametric ANOVA, Spearman’s rank correlation, Bonferroni correction and Mann Whitney U comparisons. | Male (n= 39) and female (n = 37) adult participants including HIV-1 infected ART experienced, naïve, and HIV-1 non-infected people who injection heroin, and healthy controls in Mombasa, Kenya. | HIV uninfected people who injected heroin had lower ALT levels. All had lower aspartate aminotransferase to ALT values and higher CRP levels. CD4+ T cells correlated with ALT and CRP in HIV negative and ART-experienced respectively. These offer useful laboratory markers for screening injection heroin users in initiating and monitoring anti-retroviral treatment. |

| The association between psychopathology and substance use: adolescent and young adult substance users in inpatient treatment in Cape Town, South Africa | 2014/Saban et al. [63] | Interview with quantitative analysis | 95 inpatient substance users in Cape Town, South Africa | Heroin (53.7%) and crystal methamphetamine (33.7%) were the most common substance for which treatment was sought. Anti-social personality disorder (87.4%) and conduct disorder (67.4%) were the most common comorbid psychopathologies. |

| Methadone treatment for HIV prevention—feasibility, retention, and predictors of attrition in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania: A retrospective cohort study | 2014/Lambdin et al. [64] | Retrospective cohort study of methadone-naïve patients enrolling into methadone maintenance treatment. Used Kaplan-Meier survival curves to assess retention probability, and proportional hazards regression model to evaluate association of characteristics with attrition from methadone program | 629 PWID enrolled in methadone treatment from February 2011 to January 2013 at Muhimbili National Hospital in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. 93% were male, average age at enrollment was 32 years. | Clients who were younger, male, had a history of risky sexual behavior, or history of sexual abuse had higher rates of attrition from program. Patients receiving higher doses of methadone had lower risks of attrition. At 12 months, 57% of clients were retained in care. Female clients had a lower likelihood of attrition. |

| Naltrexone implant treatment for buprenorphine dependence—Mauritian case series | 2014/Jhugroo et al. [65] | Observational case series on patients who received double naltrexone implant treatment | 24 patients with OUD presenting for treatment who were using buprenorphine and wishing to cease. None had achieved more than three weeks abstinence on methadone. Age 19–28 years and injecting buprenorphine tablets daily in Mauritius | All patients remained abstinent for 6 months; at 1 year, 83% were still abstinent. 19/24 patients attempted unsuccessfully to override the naltrexone implant blockade by injecting buprenorphine or heroin in the first four weeks after treatment. 6–18 months after treatment, 3 patients had repeat implants. Sustained-release naltrexone implant treatment may be an option for patients with OUD due to buprenorphine. |

| Active case finding for tuberculosis among people who inject drugs on methadone treatment in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania | 2014/Gupta et al. [66] | Administered questionnaire to determine prevalence of tuberculosis among PWID on methadone | 150 PWID newly started on methadone in Tanzania | 11% had one or more TB symptoms, and six new TB cases were identified, with a prevalence of 4%. This is 23 times that of the general Tanzanian TB prevalence of .2%, which has significant implications for TB control. |

| Mental and substance use disorders in Sub-Saharan Africa: Predictions of epidemiological changes and mental health workforce requirements for the next 40 Years | 2014/Charlson et al. [6] | Based on the Global Burden of Disease 2010 study, burden of disease estimates were produced for 20 mental and substance use disorders. Disability estimates from 2010 – 2050 were calculated for the East, West, Central, and Southern Sub-Saharan African regions. Service requirements and disease prevalence estimates for 2010 and 2050 were also calculated, as well as treatment coverage targets and care packages for the priority disorders, staffing ratios, and full time equivalent (FTE) staffing estimates by service type. | N/A | From 2010 to 2050, it is estimated the population will double in size and age. There will be a one and half fold increased in disability burden associated with non-communicable compared to communicable diseases. All Sub-Saharan African regions will experience an increase in burden of 130% for mental and substance use disorders, which are the leading cause of disability. There is a large gap between estimated minimum FTE staffing requirements in the health sector for 2010 and the actual FTE staffing numbers. Reaching FTE targets for service requirements requires a shift from current practice in most African countries. |

| Latent class analysis of polysubstance use, sexual risk behaviors, and infectious disease among South African drug users | 2013/Trenz et al. [67] | As part of the international NEURO-HIV Epidemiologic Study, latent class analysis was used to identify patterns of drug use among polysubstance users within a high HIV prevalence population. Multivariate logistic regression compared classes on demographics, sexual risk behavior, and disease status. | 409 drug users (209 women and 200 men). Participants were between the ages of 18 and 40, used non-injection and/or injection drugs in the past six months, and lived in/around Pretoria, South Africa. 94% identified as Black. | Identified classes included: MJ + Cig (Marijuana + cigarettes, 40.8% of sample), MJ + Her (Marijuana + heroin, 30.8%), Crack (Crack, 24.7%), and Low Use (marijuana + cigarettes, marijuana + heroin, and alcohol use, 3.7%). The MJ + Cig class was 6.7 times more likely to use alcohol and 3 times more likely to use drugs before/during sex with steady partners than the Crack class. The MJ + Cig class was 16 times more likely to use alcohol before/during sex with steady partners than the MJ + Her class. The Crack class was 6.1 times more likely to engage in transactional sex and less likely to use drugs before/during steady sex than the MJ + Her class. Patterns of drug use differ in sexual risk behaviors. |

| New evidence on the HIV epidemic in Libya: why countries must implement prevention programs among people who inject drugs. | 2013/Mirzoyan et al. [68] | Cross sectional survey using respondent driven sampling. Blood samples for HIV, HCV, and HBV testing along with behavioral data. | 328 PWID | 87% HIV prevalence, 94% HCV prevalence and 5% HBV prevalence. Most respondents (85%) reported having shared needles. 34% reported injecting for more than 15 years. |

| Identifying programmatic gaps: Inequities in harm reduction service utilization among male and female drug users in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania | 2013/Lambdin et al. [69] | Utilized routine outreach data and baseline data on clients enrolled in methadone to assess gender inequities in utilization of outreach and MOUD services and evaluate differences in HIV risk behaviors between female and male PWID. Binomial regression estimated adjusted relative risk estimates comparing females to males. | 1851 patients (92% male) who received community-based outreach services from the Tanzanian AIDS Prevention Program from December 2010 – mid-August 2012 in Kinondoni district, Tanzania. Also 443 people enrolled in the methadone program at Muhimbili National Hospital. | 8% or less of people who used drugs accessing services were women, though 34% of PWID are female. Female PWID were more likely to report multiple sex partners, anal sex, commercial sex work, and struggle under a higher burden of addiction, mental disorders, and abuse. A clear need exists for women-centered strategies that effectively engage female PWID into HIV prevention services. |

| A profile on HIV prevalence and risk behaviors among injecting drug users in Nigeria: Should we be alarmed? | 2013/Eluwa et al. [5] | Cross-sectional design using respondent driven sampling conducted in six states to investigate prevalence and correlates of HIV among injecting drug users in Nigeria. Weighted HIV prevalence and injecting risk behaviors calculated using RDS analytic tool, logistic regression used to determine correlates of HIV infection. | 273, 271, 270, 273, 196, and 191 IV drug users in Cross River, FCT, Kano, Oyo, Kaduna, and Lagos states respectively in Nigeria. Recruited from 6 urban centers. | Total numbers of PWID ranged from 197 in Lagos to 273 in Cross River and Oyo states. HIV prevalence highest in Federal Capital Territory (FCT). Females had higher HIV prevalence in all states except FCT, though >90% of participants were male. For injecting risk behavior, only receptive sharing was associated with HIV in Oyo and Kaduna states respectively. There is a need for targeted HIV interventions for females, and community-based opioid agonist treatment and needle exchange programs should be implemented. |

| An urgent need to scale-up injecting drug harm reduction services in Tanzania: prevalence of blood-borne viruses among drug users in Temeke District, Dar-es-Salaam, 2011 | 2013/Bowring et al. [70] | Behavioral survey alongside repeat rapid HIV and HCV antibody testing | 267 PWID and 163 non-injecting drug users (heroin and/or cocaine use) from Temeke district, Tanzania | Among PWID, 34.8% tested HIV positive and 27.7% HCV antibody positive. 97% were aware of HIV and 34% of HCV. High prevalence of HIV and HCV were detected in the population of PWID, necessitated rapid scale up of targeted primary prevention, testing, and treatment services in Tanzania for this population. |

| A descriptive survey of types, spread and characteristics of substance abuse treatment centers in Nigeria | 2011/Onifade et al. [71] | Cross sectional online survey of substance use treatment centers, analyzed using descriptive statistical analysis | 31 substance use treatment centers in Nigeria, with 48% located in the South-West zone of the country | 58.1% owned by NGOs, most often provided short-term crisis or informal counseling support for people with substance use. Average of 33 staff per unit. The 16 residential units provided no medication treatment. Suggests a shortage of substance abuse treatment units in Nigeria, with under-funding and inadequate government attention. Recommend organization and centralization of substance abuse treatment centers with increased governmental role. |

| Rapid assessment response (RAR) study: drug use and health risk - Pretoria, South Africa | 2011/Dos Santos et al. [72] | Rapid assessment response using observation, reviewing existing information, mapping of service providers, key informant interviews, and focus groups. Utilized purposive and snowball sampling, and thematic analysis. | 63 drug using key informants (49 males, 14 females) and 21 service providers (8 male, 13 female) in Pretoria, South Africa | Key informants felt that black communities, especially men, were most affected by substance use in Pretoria, and poverty made access to treatment harder. Heroin availability was increasing and the most problematic. Knowledge regarding HIV/AIDS transmission not yet widespread. HIV testing/treatment must be accessible to people who use drugs, and policies to reduce harmful consequences of substance use and HIV/AIDS should be implemented. |

| Evidence of high-risk sexual behaviors among injection drug users in the Kenya PLACE study | 2011/Brodish et al. [73] | Priority for Local AIDS Control Efforts (PLACE) study conducted to identify areas where HIV transmission likely. Sites randomly sampled and individuals interviewed at each location, using univariate, bivariate, and multivariate logistic regression for data analysis. | 20 individuals and 4 workers interviewed at each of 29 venues where PWID meet new sexual partners and places where drugs can be accessed in Malindi, Kenya. | Nearly half of PWID reported sharing syringes when injecting, and 42% reported taking drugs from a common reservoir. Most could inconsistently get new syringes. Multiple sexual partnerships and risky behaviors are likely facilitating HIV transmission. |

| HIV risk behaviours, perceived severity of drug use problems, and prior treatment experience in a sample of young heroin injectors in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania | 2011/Atkinson et al. [74] | Computer assisted survey interview, with participants recruited through targeted sampling, modified snowball sampling, and RDS. Statistical analysis utilized independent-samples t-tests and chi square tests. | 298 individuals (203 male and 95 female) between ages of 16–25 who had injected heroin in the previous week and willing to undergo HIV testing | Sexually active females had a mean of 54.6 partners and 82% had traded sex for money in the previous 30 days. 12% of males and 55% females were HIV seropositive. There is an unmet need for heroin treatment, and efforts to help women transition away from survival sex may be warranted. |

| HIV prevalence and risk behaviors of male injection drug users in Cairo, Egypt | 2010/Soliman et al. [75] | RDS in a cross-sectional study with face-to-face interviews and HIV antibody testing. | 413 men over 18 years of age who had injected recreationally in previous month in Cairo, Egypt. | More than half reported injecting with used needles, and 32.4% shared syringes with one or more persons in the previous 30 days. Use of condom during sex was low. 6% was the population estimated HIV prevalence. This demonstrates relatively low HIV infection prevalence compared to global estimates, with high incidence of risky injection practices and unprotected sex. |

| Opportunities for enhancing and integrating HIV and drug services for drug using vulnerable populations in South Africa | 2010/Parry et al. [76] | Rapid assessment using key informants and focus groups interviews with drug users and service providers, analyzed qualitatively. | In Phase 1 (2005), 131 key informant interviews with drug users and 21 focus interviews with 109 participants who were drug users in Durban, Cape Town, and Pretoria. 19 service providers were interviewed. In Phase 2 (2007), 69 drug users were interviewed in focus groups and 11 service providers. | People who used drugs had various risk factors for HIV transmission, and limited knowledge of drug treatment availability. Those who accessed treatment identified many barriers, as did service providers. There are several misperceptions about HIV and limited access to preventive materials. Service providers reported barriers to integrating HIV and substance use services. A comprehensive and accessible intervention to prevent HIV risk in drug users must be developed. |

| Flashblood: blood sharing among female injecting drug users in Tanzania | 2010/McCurdy et al. [77] | Cross-sectional design to examine association between flashblood practice and demographic factors, HIV status, and variables associated with risky sex and drug behaviors. Statistical analysis utilized t-tests and chi square tests. | Out of 169 female injecting drug users who were interviewed, 28 reported ever using flashblood in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. | Those who practiced flashblood were more likely to be married, lived in their current housing situation for a shorter time period, forced as a child to have sex by a family member, inject heroin more in the last 30 days, smoke marijuana at an earlier age, use contaminated rinse-water, pool money for drugs and share drugs. Those who did not engage in flashblood practice were more likely to live with their parents. Practice of flashblood spreading from the inner city to the suburbs. |

| HIV risk and the overlap of injecting drug use and high-risk sexual behaviours among men who have sex with men in Zanzibar (Unguja), Tanzania | 2010/Johnston et al. [78] | Respondent driven sampling with face-to-face interviews and HIV, HBV, HCV, and syphilis testing. | 509 MSM who were ≥ 15 years old, reported anal sex with another man in the past 3 months, and living in Unguja, Zanzibar. | 14% reported injecting drugs in the past 3 months, among which 66% used heroin, 60% used a needle after someone else used it, and 68% passed a needle to someone else after using it. MSM who were IDUs were more likely to have STI symptoms in the past 6 months, to be HIV-positive, and co-infected with HIV and HCV, and less likely to ever been tested for HIV and know where to get a confidential HIV test compared to MSM who did not inject drugs. Targeted interventions need to account for overlap of high-risk sexual and drug-using networks that put MSM at risk for transmission of HIV and HCV infection; need integration of injection drug use and HIV services. |

| An approach to heroin use disorder intervention within the South African context: a content analysis study | 2010/Dos Santos et al. [79] | Semi-structured interviews. | 10 purposively sampled heroin use disorder specialists in South Africa. | Heroin use disorder interventions and programmes have begun to be implemented within the South African context; however, comorbidity factors such as psychiatric illness and HIV needs to be further addressed. Additionally, evidence-based public health policies to reduce the harmful consequences of heroin use still needs to be implemented. |

| HIV seroprevalence in a sample of Tanzanian intravenous drug users | 2009/Williams et al. [80] | Participants were recruited using a combination of targeted sampling (by an outreach worker) or participant referral (from a larger condom use study among sexually active PWID) to assess factors associated with HIV acquisition risk. Blood specimens and self-reported socioeconomic status and behavioral data were collected. Data were analyzed using univariate odds ratios and multivariate logistic regression. | 315 male and 219 female PWID in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania who were recruited from a larger study exploring condom use in sexually active PWID. For participation in the study, participants had to be ≥ 18 years, injected an illicit drug in the past 48 hours, had sex at least once during the past 30 days, and willing to provide a blood specimen. | 42% of the samples tested positive for HIV. The factors independently associated with HIV infection risk were having sex more than 81 times in the past 30 days, earning less than 100,000 shillings (US$76) in the past month, residing in Dar es Salaam for less than 5 years, and injecting for 3 years. The high rate of HIV infection suggests that injecting drug use may be a contributing factor in the continuing epidemic in sub-Saharan Africa. |

| HIV-risk behavior among injecting or non-injecting drug users in Cape Town, Pretoria, and Durban, South Africa | 2009/Parry et al. [81] | Rapid assessment using key informants and focus groups (FG) interviews with injection and non-injection drug users, analyzed qualitatively. Key informants (KI) tested for HIV. | 85 individuals (42 KI and 43 FG participants) who were ≥ 18 years, able to understand and speak English, self-reported drug use (injection and non-injection) in the past week, not violent/mentally ill, and did not have drug treatment within the past month. Majority KIs were male (86%). | Risky injecting behaviors among PWID were common, most engaged in sex when on drugs, some without condoms. 20% of PWID who agreed to HIV screening, tested positive. PWID seemed more knowledgeable about HIV transmission than those who did not inject drugs. Views about drug- and HIV-intervention services, accessibility, and their efficacy were mixed. Findings suggest risk-reduction strategies should be made more accessible, and that greater synergy is needed between drug- and HIV-intervention areas. |

| Drug use careers and blood-borne pathogen risk behavior in male and female Tanzanian heroin injectors | 2008/Ross et al. [82] | Data collected from the Tanzanian AIDS Prevention Project questionnaire to examine HIV risk behaviors and drug using careers that culminated in heroin use among injecting drug users. | 537 PWID (56% males and 44% females) in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. | First drugs reported for males and females were marijuana, alcohol, and heroin. Females had shorter drug careers than males, and time from first use of heroin to first injection also shorter for females. Years injecting was a mean of 5 years for males and 3 years for females. More than 90% of females and only 2% of males reported ever trading sex for money. >90% of males and females reported using new needles for injection. Findings confirm that heroin injecting is well established in large cities in east Africa and that HIV prevention will need to include focus on this population. |

| Heroin users in Cape Town, South Africa: injecting practices, HIV-related risk behaviors, and other health consequences | 2008/Pluddemann et al. [83] | Snowball or chain referral sampling to investigate HIV-related risk behaviors among heroin users. | 239 people who used heroin in Cape Town, South Africa were interviewed using a structured questionnaire. Predominantly males (79%), and mean age was 23.5 years (SD=3.96). | 24% of all the participants reported injected heroin use in the past 30 days and 89% of these shared a needle at least once during that period. Condom use was irregular. 3% self-reported that they were HIV positive. Heroin use has become a major concern in Cape Town and may still be increasing. Injecting heroin use still appears to be limited, but this has the potential to change. |

| Rapid assessment of drug use and sexual HIV risk patterns among vulnerable drug-using populations in Cape Town, Durban and Pretoria, South Africa | 2008/Parry et al. [84] | Rapid assessment using key informants and focus groups interviews with commercial sex workers (CSWs), MSM and injection and non-injection drug users, and service providers analyzed qualitatively to examine link between drug use, risky sexual practices and HIV. Key informants tested for HIV. | 131 KI interviewees and 109 focus group interviewees (21 FGs). Mean age was 28.6 years (Range 18–62 years old). Majority were men (65%). Final sample of drug users comprised 78 MSM, 115 CSWs and 96 PWID and 45 non-injecting individuals who were not MSM or CSWs. Some people who used drugs fit into more than one category. | Drug users reported selling sex for money to buy drugs. CSWs used drugs before, during and after sex. 70% of KIs tested for HIV and 28% were positive, with highest rates among MSM and CSWs. PWID reported needle sharing behavior. There was a widespread lack of awareness about where to access HIV prevention and treatment services. Numerous barriers to accessing HIV and drug intervention services reported. Targeted interventions are needed to reach this vulnerable population and limit the spread of HIV. |

| Sex, drugs, and HIV: rapid assessment of HIV risk behaviors among street-based drug using sex workers in Durban, South Africa | 2008/Needle et al. [85] | Rapid assessment using key informants and focus groups interviews conducted to learn more about patterns of drug use and HIV risk behaviors among drug-using, street-based sex workers. Key informants tested for HIV. | 52 (27 men and 25 women) current injection and non-injecting individuals engaged in sex work in Durban, South Africa. 28 KI and 5 focus groups conducted. Thirty-three were without injection (15 men and 18 women); 19 were PWID (12 men and 7 women). Average age for females was 28 years, 31 years for males. | Findings indicate that in this population, drugs play an organizing role in patterns of daily activities, with sex work closely linked to the buying, selling, and using of drugs. Participants reported using multiple drugs. Organization of sex work and patterns of drug use differed by gender, with males having more control over their daily routines and drug and sexual transactions than females. Mixing patterns across drug and sexual risk networks have the potential to accelerate HIV spread. |

| Differences in HIV risk behaviors by gender in a sample of Tanzanian injection drug users | 2007/Williams et al. [86] | Data were collected using the Peer Outreach Questionnaire to examine drug use and sexual behaviors. Multivariate logistic regression estimated risk of needle sharing. | 237 male and 123 female people who used heroin in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Average age of men were 28 years and women were 24.4 years. | Men were significantly older, more likely to inject only white heroin, share needles, and give or lend used needles to other injectors. Women were more likely to be living on the streets, inject brown heroin, have had sex, have had a higher number of sexual partners, traded sex for money and drugs, diagnosed with an STI in the last 12 months, and have used a condom with the most recent sex partner. Predictors of increased risk of needle sharing were being male and earning less than US$46 in the past month. |

| HIV/AIDS and injection drug use in the neighborhoods of Dar es Salaam, Tanzania | 2006/McCurdy et al. [87] | Used syringes collected from IDUs to examine needle sharing practices and HIV. Semistructured interviews were also conducted and qualitatively analyzed. | Used syringes collected from 73 heroin injection drug users. 51 semistructured face-to-face interviews conducted with IDUs (33 men and 18 women) in neighborhoods of Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. | Thirty-five (57%) of the useable syringes tested positive for HIV antibodies. Results varied significantly: 90% of syringes tested HIV positive in mixed-income neighborhood 2 kilometers from the city center; with 0% of syringes testing HIV positive in the outlying areas. Semistructured interviews with confirmed that syringes were shared widely. Findings suggest that HIV is being transmitted by needle- and syringe-sharing practices, thereby creating the possibility of a new wave of HIV transmission in Dar es Salaam, if not Tanzania. |

| A rapid assessment of heroin use in Mombasa, Kenya | 2006/Beckerleg et al. [88] | Rapid assessment using key informant interviews, questionnaires, informal interviews and feedback from local agencies working with PWID. | 496 people who used heroin interviewed (95% were men and 5% were women) in Mombasa, Kenya. | Overall, 15% of respondents had “ever injected” heroin, and 7% were current injectors (n=37); 7% likely to be an underestimate. Most injectors reported using a syringe for 1–3 days. Majority reported injecting in a group of three or more and described risk behaviors for HIV transmission. Results highlight the need for a range of services, including needle exchange, counseling, and referral to residential treatment programs. |

| Heroin treatment demand in South Africa: trends from two large metropolitan sites (January 1997-December 2003) | 2005/Parry et al. [89] | Surveillance data were collected to provide information on nature and extent of heroin use. | 41 specialist alcohol and other drug treatment centers in two metropolitan sites in Cape Town and Gauteng Province, South Africa. | Treatment indicators point to a substantial increase in heroin use over time. Most who used heroin in treatment tend to be white, male, between the ages of 21 and 24 years and tend to smoke rather than inject the substance. However, emerging trends point to changes in heroin use patterns, demonstrating the need for continued monitoring of the situation. |

| Heroin and HIV risk in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania: youth hangouts, mageto and injecting practices | 2005/McCurdy et al. [90] | Semi-structured interviews were conducted to ascertain practice of those who use heroin, interactions and narratives for insights into appropriate HIV prevention interventions. | 51 injectors (18 female and 33 males) residing in 8 neighborhoods in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. | Emergent themes around hangout places, initiation of heroin use, and progression to injecting were qualitatively analyzed. Injecting is a recent practice in Africa and coincides with Tanzania transitioning to a heroin consuming community, importance of youth culture, innovation of injecting practices, intro and ease of use of white heroin, and perceived need to escalate use to a more effective form of heroin ingestion. |

| Indicators of substance abuse treatment demand in Cape Town, South Africa (1997–2001) | 2004/Myers et al. [91] | Descriptive epidemiological information about patterns of alcohol and other drug (AOD) treatment services utilization for purpose of informing policies and practice related to substance use interventions in the region. | Specialist substance use treatment centers to describe substance use treatment demand and patters of service utilization in Cape Town, South Africa. | Treatment demand for alcohol related problems remain high. Treatment demand for other substances not related to alcohol has increased over time. Increased use of treatment service utilization by adolescents, while patterns suggest that women and black South Africans remain underserved. Recommendations are to improve access to substance use treatment services. |

| The South African Community Epidemiology Network on Drug Use (SACENDU): description, findings (1997–99) and policy implications | 2002/Parry et al. [92] | Descriptive epidemiological study of AOD indicators. Purpose was to describe the South African Community Epidemiology Network on Drug Use (SACENDU), describe trends and associated consequences of alcohol and other drug (AOD) use in South Africa, and outline policy implications identified by SACENDU participants. | Data gathered from multiple sources, including specialist treatment centers (>50), trauma units and quantitative studies of target groups such as school students and arrestees. Networks were established in five sentinel sites (Cape Town, Durban, Port Elizabeth, Gauteng, Mpumalanga) to facilitate the collection, interpretation and dissemination of data. | Alcohol reported as the most common substance of abuse across sites. Most frequently reported illicit drugs of abuse were cannabis and mandrax (methaqualone) either alone or in combination. Use and burden of illicit substances is on the rise. There was a significant increase in cocaine/crack and heroin use in two sites. There was an increase in the use of ecstasy (MDMA), either alone or in combination with other substances, reported among young people. Possible solutions include increasing the number of AOD treatment options, especially among marginalized groups; providing specific treatment protocols for specific drugs for substance use practitioners; developing protocols for the identification, management and treatment of patients in general hospitals, primary health-care settings, trauma units, etc.; and developing age-appropriate AOD prevention programs. |

| Substance abuse in outpatients attending rural and urban health centres in Kenya | 2000/Othieno et al. [93] | Descriptive cross-sectional survey to estimate prevalence and pattern of substance use among patients at primary health centers in urban and rural settings. | 150 adult patients (78 males and 72 females) from urban health centers of Jericho and Kenyatta University (KU) and rural health centers in Muranga district. | Substances most commonly used were alcohol, tobacco, khat, and cannabis. Rates of substance use was generally low except for alcohol and tobacco. Lifetime prevalence of alcohol use for the two urban health centers were 54% and 62% compared to 54% for the rural health centers. For tobacco the lifetime prevalence was 30% for Jericho, 28% for KU and 38% for Muranga. The differences between the rural and urban samples were not statistically significant. More males than females had significantly used alcohol (80.8% vs 30.6%) and tobacco (56.4% vs 5.6%). |

Epidemiology

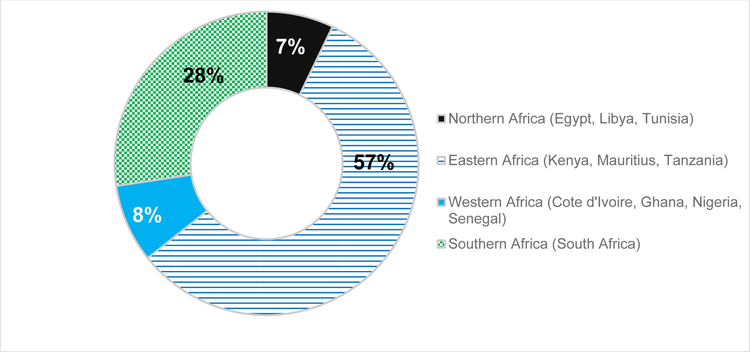

Opioid and other substance use continues to grow throughout multiple African jurisdictions. Most of the published studies and articles that we found were from the east African region (see Figure 1). Many describe patterns of drug use. Heroin trafficking and use in Kenya and Tanzania, for example, have been noted to have escalated [94]. Reviews by the United Nations Office on Drugs & Crime (UNODC) and WHO [95] find that injecting drug use (IDU) in Africa is increasing [2].

Figure 1.

Geographic Distribution of Publications

Mental health disorders are prevalent among people who use drugs and successful treatment for OUD requires a recognition of co-occurring mental illness and evidence-based treatments for these disorders. While a full discussion of mental health in Africa is beyond the scope of this discussion, it is worth noting that the burden of mental health and substance use disorders in Africa were, at 19% of the total burden, the leading cause of years lived with disability (YLD) in sub-Saharan Africa in 2010 [6].

Impact on Women

A common theme was the lack of targeted interventions for women who use drugs who often did not self-identify to researchers; most populations sampled in the papers published were primarily male. While most of the published papers had majority male samples with very few females noted [17, 20, 96], some community estimates have shown a somewhat higher prevalence of females with substance use disorder – up to 10% of individuals with substance use disorders in Kenya as noted by the UNODC, e.g. [17, 20].

For many persons in Africa with OUD, challenges occur around stigma, persecution by police, incarceration, condemnation from religious and community leaders, and barriers to MOUD. It is important to point out specific subpopulation issues in OUD in Africa. Women who have OUD often are at a distinct disadvantage in terms of barriers to accessing services, differential gender and power norms in society, child care, a high prevalence of violence [32], and poverty. When services such as methadone treatment exist, they are often dominated by men, making it uncomfortable or unsafe for women who may be victims of violence to wait in line. Women may engage in sex work to support their OUD, leading to exposures, more violence and HIV/HCV infection from not only parenteral but sexual risk patterns.

Injection Drug Use

People who inject drugs (PWID) are an additional subpopulation of note that is growing in some countries in Africa. Access to MOUD and NSP are outpaced by opioid trafficking and HIV/HCV. In 2014, the Tanzania National AIDS Control Programme (NACP) estimated that there were approximately 30,000 PWID in the country (mainland), with 35% living with HIV [97]. Comprising a growing proportion of HIV transmissions in the region, they have been a politically powerless group that has lacked access to addiction treatment and HIV prevention and often faces persecution from police and communities [98]. Furthermore, HIV testing/treatment and addiction treatment services are rarely integrated, creating more services access barriers [99].

Tramadol

Additional literature has pointed out that use of tramadol (which is not listed as a controlled substance regulated by the International Narcotics Control Board) is increasing; codeine misuse has also been noted in South Africa [23] as well as other countries in Africa. The UNODC pointed out in 2017 that tramadol trafficking from Asia to central and west African countries through militant groups including Boko Harem has both increased dramatically (yearly seizures from 300 kg to more than 3 tons) and is contributing to political destabilization in the region [100]. While tramadol is a relatively safe analgesic when used at therapeutic doses, misuse can result in dependence, withdrawal, overdose [101], and intoxication when co-ingested with other drugs or alcohol. Tramadol may also predispose to other addictions such as nicotine/cigarette smoking [102].

Prevention and Treatment

It is encouraging that at least some OUD-specific prevention and treatment services are growing in Africa. Csete et al. noted 10 years ago that, in “almost all countries of sub-Saharan Africa, including those most affected by HIV, affordable drug-dependency treatment is out of reach, needle exchange does not exist, and legal services are unavailable or unaffordable [103].” In 2018, the situation has improved somewhat, with public methadone available in Kenya and Tanzania, and NSPs in those countries and a handful of others. However, these services are not yet the norm in many countries.

A handful of papers in our review discussed addiction treatment models, such as the Matrix model in South Africa, but these have not focused specifically on evidence-based models of care for people who use opioids.

A decade ago the 2008 review by Mathers of NSP and MOUD coverage among the then-148 countries reporting HIV among PWID found that coverage was lowest in sub-Saharan Africa [95]. Ten years later, there are still estimated to be only five countries in sub-Saharan Africa with NSP: Mauritius, Senegal, Tanzania, Kenya and South Africa [104]. While countries were struggling on the mainland to begin treatment options, Mauritius launched a robust response using NSP and MOUD [105]. Starting in 2011, Tanzania [106], and thereafter Kenya [14, 52, 107], launched opioid treatment programs to address the opioid epidemic. With the successes of these programs, many additional countries have started to discuss opioid treatment as a way to address the opioid epidemic in Africa, including Mozambique, Senegal, and Nigeria. (R. Douglas Bruce, personal communication, June 2018).

Infectious Diseases

Opioid use contributes to HIV and HCV transmission, particularly when parenteral methods are used for drug consumption, and with tuberculosis transmission. Nearly half of Africa’s 54 countries had recognized the injection of drugs, particularly opioids, as an HIV risk factor, almost a decade ago [5]. In Kenya it is estimated that 18.7% of incident HIV infections on the Kenyan coast and 7.5% nationally are attributed to opioid injection.