Abstract

Symmetrical, near-infrared absorbing bacteriochlorin dyads exhibit gradual reduction of their fluorescence (intensity and lifetime) and reactive oxygen species (ROS) photosensitization efficiency with increasing solvent dielectric constant ε. For the directly-linked dyad significant reduction is observed even in solvents of moderate ε (CH2Cl2), while for the dyad containing a 1,4-phenylene linker, reduction is more parallel to an increase in solvent ε. Bacteriochlorin dyads are promising candidates for development of environmentally responsive fluorophores and ROS sensitizers.

Graphical Abstract

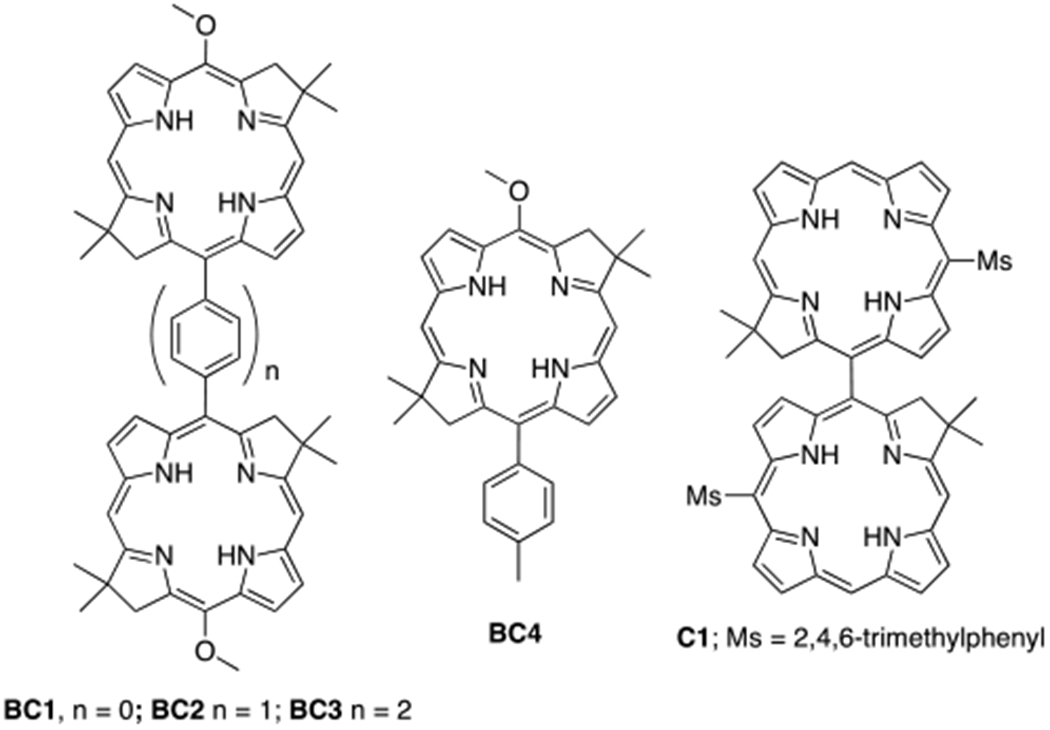

Photonic agents with photochemical properties responsive to the local microenvironment are of great interest, since they can function, for example, as fluorescent probes that monitor a variety of biological and biochemical processes1 or photosensitizers of reactive oxygen species (ROS), selectively activated by a specific microenvironment.2,3,4 Dielectric properties expressed by the dielectric constant ε vary significantly between intracellular organelles5,6 and macrobiomolecules.6–8 Recent findings also suggest that the local polarity (which is a function of ε) in the mitochondria of cancerous cells is lower compared to that of healthy ones.9 Therefore, the local ε can be a potential target for activation of imaging or therapeutic agents. Although there is a plethora of solvatochromic fluorophores,1,9,10 only a few of them have been utilized for determination of intracellular ε,5,8 and there are only a handful of ROS photosensitizers which respond in predictable manner to the local dielectric properties.2,3,4 However, the majority of ε–responsive fluorophores and photosensitizers absorb and emit at λ < 600 nm, while these with excitation/emission at λ > 650 nm, suitable for deep-tissue applications, are less common.10 Moreover, such ε-responsive agents reported so far can usually perform either fluorescence or ROS sensitization functions, separately. Bacteriochlorins, strongly near-infrared (near-IR) absorbing tetrapyrrolic macrocycles, exhibit relatively high both fluorescence quantum yield (Φf) and quantum efficiency of ROS photosensitization (ΦROS, ROS include singlet oxygen 1O2, and superoxide radical O2-·).11,12 The relatively high ΦROS for bacteriochlorins originates from high yield of intersystem crossing (ΦISC), leading to the long-living triplet state, capable of transferring either energy or electron to oxygen, to produce 1O2 or O2-·, respectively.12 Thus, bacteriochlorins are utilized as near-IR fluorophores, ROS photosensitizers for photodynamic therapy, and both simultaneously.12,13 Recently, we found that strongly conjugated bacteriochlorin arrays exhibit a significant reduction in both Φf and τf in solvents of high ε, due to the greatly enhanced internal conversion.14,15 We reasoned that similar dependence should be true for ΦROS, thus allowing bacteriochlorin dyads to function as ε-dependent ROS photosensitizers. However, strongly-conjugated bacteriochlorin dyads exhibit a low ΦISC (i.e. 0.09 – 0.39)15 and consequently, low ΦROS even in non-polar solvents [see Supporting Information (SI) for an example). Therefore, here we describe a new series of weakly-conjugated bacteriochlorin arrays, where bacteriochlorin subunits are connected either directly (BC1), or through 1,4-phenylene (BC2), or 4,4′-biphenylene (BC3) linkers. Our hypothesis is that such constructs should exhibit a relatively high Φf and ΦROS in solvents of low ε, and both of them will be reduced with increasing solvent polarity. As benchmarks we include bacteriochlorin monomer BC4, and directly-linked chlorin dyad C1, analogous to BC1, to determine whether observed properties are specific to bacteriochlorin dyads (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Structures of compounds BC1–4 and C1

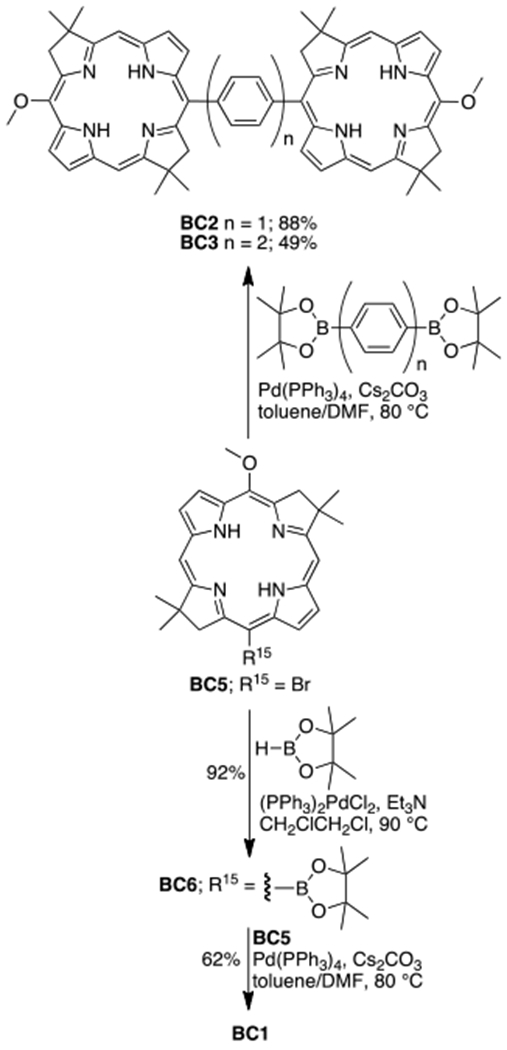

Synthesis of BC1 starts from Miyaura borylation of known 15-bromobacteriochlorin BC5,16 which provides a boronic ester BC6 in excellent yield (92%). Subsequent Suzuki coupling of BC6 with BC5, provides BC1 in 62% yield.17 Suzuki reaction of BC5 with 1,4-bis(4,4,5,5-tetramethyl-1,3,2-dioxaborolan-2-yl)benzene or 4,4’-bis(4,4,5,5-tetramethyl-1,3,2-dioxaborolan-2-yl)-1,1’-biphenyl provides BC2 (88% yield) or BC3 (49% yield), respectively. Monomer BC4 was synthesized in similar Suzuki reaction (Scheme S1, SI). Chlorin dyad C1 was prepared following a published procedure,18 via PIFA-mediated oxidative coupling of monomer ZnC2, and subsequent demetalation of resulted complex ZnC1 (Scheme 2). All new compounds show 1H, 13C NMR, and MS data consistent with expected structures. Note, that both BC1 and C1 are axially chiral, and accordingly, their 1H NMR spectra show distinctive resonances of diastereotopic protons.

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of dyad C1

The absorption spectra of BC1-4 (Figure 2, Table 1) contain features typical for synthetic bacteriochlorins reported previously,11 i.e. strong Qy-type bands in the near-IR spectral window (712-738 nm), Qx–type bands in the visible window (500-510), and B-type bands in UV range (365-370 nm), Note that the Qy band for BC1 is split with the second maximum at 706 nm. Emission spectra in toluene consist of narrow 0-0 bands, with small (<7 nm) Stokes’ shift versus the Qy-type band. The maxima of both Qy-type absorption and emission for dyads are shifted bathochromically, compared to corresponding bands in monomer BC4; the most pronounced shift is observed for BC1 (365 and 436 cm−1 for absorption and emission, respectively), and is much lower for BC2 (98 cm−1 and 116 cm−1) and BC3 (39 cm−1 for both absorption and emission). The positions of absorption and emission maxima vary only slightly in solvents of different polarities (Table S1, SI). The linker-dependent, bathochromic shifts of both the Qy absorption and emission bands is indicative of increasing electronic communications between bacteriochlorin subunits in dyads with decreasing distance between them.

Figure 2.

Absorption spectra of BC1–4 in toluene: BC1 (black, solid), BC2 (blue), BC3 (red), and BC4 (black, dotted). All spectra are normalized at the B-bands maxima.

Table 1.

Photophysical properties of BC1–4 and C1 in solvents of different dielectric constants.a)

| Solvent | Φf | τf [ns] | ϕROSb) |

|---|---|---|---|

| BC1: λQy = 706, 731 nm, λem = 738 nm (in toluene) | |||

| Toluene | 0.28 | 3.6 | 1.00 |

| THF | 0.20 | 3.1 | 0.87 |

| CH2Cl2 | 0.037 | 0.48 | 0.097 |

| PhCN | 0.031 | < 0.4c) | ndd) |

| MeOHe) | 0.007f) | < 0.4c) | ndd) |

| DMF | 0.003f) | < 0.4c) | 0.008 |

| BC2: λQy = 717 nm, λem = 721 nm (in toluene) | |||

| toluene | 0.22 | 4.1 | 1.00 |

| THF | 0.20 | 4.2 | 1.08 |

| CH2Cl2 | 0.17 | 3.6 | 0.94 |

| PhCN | 0.11 | 2.4 | ndd) |

| MeOHe) | 0.069 | 2.3 | ndd) |

| DMF | 0.066 | 1.6 | 0.39 |

| BC3: λQy = 714 nm, λem = 717 nm (in toluene) | |||

| toluene | 0.22 | 4.1 | 1.00 |

| THF | 0.19 | 4.1 | 1.06 |

| CH2Cl2 | 0.18 | 3.8 | 0.91 |

| PhCN | 0.18 | 3.9 | ndd) |

| MeOHe) | 0.15 | 3.7 | ndd) |

| DMF | 0.16 | 3.7 | 0.81 |

| BC4: λQy = 712 nm, λem = 715 nm (in toluene) | |||

| Toluene | 0.22 | 4.4 | - |

| THF | 0.19 | 4.5 | - |

| CH2Cl2 | 0.19 | 4.2 | - |

| PhCN | 0.22 | 4.6 | - |

| MeOHe) | 0.15 | 4.2 | - |

| DMF | 0.20 | 4.6 | - |

| C1: λQy = 650 nm, λem = 654 nm (in toluene) | |||

| Toluene | 0.31 | 5.9 | ndd) |

| DMF | 0.29 | 6.0 | ndd) |

All data were determined in air-equilibrated solvents. For Φf and τf determination samples were excited at the maxima of their Qx band. Fluorescence quantum yields were determined with respect to meso-tetraphenylporphyrin (TPP, Φf = 0.070 in non-degassed toluene).11 The estimated error in Φf, τf, and ϕROS determination is ±10%.

For details of ϕROS determination see SI.

The τf is too short to be accurately determined by our experimental set-up.

Not determined.

5% of THF (v/v) was used as a co-solvent.

The weak emission signal at 736 nm overlaps with the second weak emission peak at 717 nm of unknown origin; therefore the Φf is approximate.

Fluorescence properties of BC1-4 and C1 (Table 1, Figures S1–S3, SI) were determined in an array of aprotic and protic solvents of broad ε range: toluene (ε = 2.38), THF (ε = 7.58), dichloromethane (CH2Cl2, ε = 8.93), PhCN (ε = 26.0), MeOH (ε = 32.7), and DMF (ε = 36.7). In toluene, BC1 shows markedly higher Φf (0.28) than BC4 (0.22), whereas both BC2 and BC3 show Φf in toluene comparable with that observed for BC4. For BC1 both Φf and τf diminish when solvent ε increases, resulting in a significant reduction of fluorescence in solvents of moderate ε (THF, CH2Cl2, PhCN) and almost no fluorescence in MeOH and DMF. A similar trend was observed for BC2; however, the reduction of both Φf and τf is less dramatic and more parallel with increase in ε of the solvents. The τf in BC2 decreases nearly linearly when ε of the solvent increases (Figure S5, SI), which suggests that this dyad can be useful as a fluorescence lifetime probe for determination of local dielectric constants. BC3 shows marked reduction of Φf in DMF only. Both BC4 and C1 show virtually no dependence of both Φf and τf on solvents ε.

These results indicate that for bacteriochlorin dyads, a new and efficient process for deactivation of the excited state, which competes with fluorescence, becomes accessible in polar solvents. The efficiency of this process clearly depends on ε of the solvent. Moreover, the efficiency of this new process appears to depend on the electronic conjugation between macrocycles in dyads, as the most extensive reduction of fluorescence in given solvent is observed for BC1 (where electronic communication between macrocycles is presumed to be the strongest)..Importantly, this process is specific only for bacteriochlorin dyads, since fluorescence properties for the monomer BC4 and for the chlorin dyad C1 are nearly solvent-independent. To the best of our knowledge, analogous porphyrin dyads show only slight dependence of their photophysical properties on solvent ε.19

Next, we determined the influence of solvent ε on ROS photosensitization for BC1-4, using 2,5-diphenylisobenzofuran (DPBF). DPBF reacts with 1O2 and O2-·, causing a decay of DPBF absorbance at 414 nm.20,21 The comparison of ΦROS for given photosensitizer in different solvents is more complex than in case of Φf discussed above. ΦROS depends on both the properties of the photosensitizer excited states (i.e. ΦISC and triplet state lifetime) as well as solvent properties such as oxygen solubility, rate of oxygen diffusion, rate of bimolecular quenching of triplet state by oxygen, etc.22 Thus, influence of a solvent on ΦROS is observed, to some extent, for many photosensitizers.23 Moreover, rate of DPBF degradation depends not only on the amount of singlet oxygen generated by the photosensitizer, but also on the lifetime of singlet oxygen in given solvents and bimolecular rate constants for reaction of singlet oxygen with DPBF, both of which vary in different solvents.24 Hence, to evaluate the influence of solvent ε on ROS photosensitization of dyads, we determined how different the influence of solvent ε on ROS photosensitization is for given dyad, compared to that of the benchmark monomer BC4. Quantitatively, this influence was expressed through relative quantum yield of ROS photosensitization ϕROS (see SI for the exact definition and measurement methodology). The ϕROS were determined for dyads BC1-3 in four solvents: toluene (as a reference solvent), THF, CH2Cl2, and DMF. The plots of rate of DPBF absorbance decays for BC1-4 are shown in Figure S8, SI, and the resulting ϕROS are given in Table 1. For BC1 we observed a dramatic reduction of ϕROS in both CH2Cl2 (10-fold) and DMF (125-fold) compared to that in toluene. For BC2 and BC3 ϕROS exhibit a lesser reduction than BC1, with the exception of DMF, for which ϕROS is significantly (2.5-fold) lower for BC2 but only slightly (1.2-fold) lower for BC3, compared to toluene. The influence of solvent ε on ϕROS reduction was further confirmed by determining the rate of DPBF decay in the presence of BC1 in a series of toluene/DMF mixtures with increasing DMF concentration. The ϕROS gradually decreases with increasing ratio of DMF in the mixture (Figure S9, SI).

The quenching of 1O2 photosensitization of BC1 in DMF was further confirmed by monitoring 1O2 luminescence at 1270 nm, which in toluene is observed for both BC1 and BC4, but in DMF it is observed only for BC4 and is completely absent for BC1 (Figure S7, SI). The quantum yields of 1O2 photosensitization (ΦΔ) in air-equilibrated toluene (determined by comparing the intensity of 1O2 luminescence generated by bacteriochlorins, to those generated by TPP) are 65% for both BC1 and BC4. ΦΔ corresponds well with ΦISC determined previously for various meso-substituted bacteriochlorins, (i.e. ΦISC = 0.54-0.71).11

In summary, fluorescence and ROS photosensitization ability in bacteriochlorin dyads are reduced when the solvent ε increases. The degree of quenching of photochemical activity in these dyads appears to be dictated by the strength of electronic interaction between bacteriochlorin subunits. This indicates, that the degree of the response of photochemical properties to the solvent ε in dyads can be adjusted for desired applications and polarity ranges, by proper molecular design (i.e. selecting the linker between bacteriochlorin subunits). These properties, along with high Φf and relatively long τf of near-IR emission, as well as high ΦΔ in non-polar environment, allow bacteriochlorin dyads to be promising platform for development of smart fluorophores and ROS photosensitizers activated in environment of low ε, and fluorescence lifetime probes for determination of local dielectric properties.

Supplementary Material

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of dyads BC1–3

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was supported by NSF CHE-1301109 and UMBC (start-up funds and SRAIS Award). N.N.E. is a member of the Meyerhoff Scholars Program at UMBC, supported by the NIGMS Initiative for Maximizing Students Development Grant (Grant 2 R25-GM55036), and CBI Program at UMBC, supported by the NIH (Grant No. 5T32GM066706). We thank Drs. Zeev Rosenzweig and Taeyjuana Y. Curry (UMBC) for help in fluorescence lifetime measurements..

Footnotes

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website.

Additional absorption and emission spectra, plots of DPBF decay in various solvents, experimental details, and copies of NMR spectra for new compounds. (PDF)

REFERENCES

- (1).Yang Z; Cao J; He Y; Yang JH; Kim T; Peng X; Kim JS Chem. Soc. Rev 2014, 43, 4563–4601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Lovell JF; Liu TWB; Chen J; Zheng G Chem. Rev 2010, 110, 2839–2857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).(a) Yogo T; Urano Y; Mizushima A; Sunahara H; Inoue T; Hirose K; Lino M; Kikuchi K; Nagano T Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 2008, 105, 28–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Hirakawa K; Nishimura Y; Arai T; Okazaki SJ Phys. Chem. B 2013, 117, 13490–13496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Hirakawa K; Hirano T; Nishimura Y; Arai T; Nosaka Y Photochem. Photobiol 2011, 87, 833–839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Hirakawa K; Harada M; Okazaki S; Nosaka Y Chem. Commun 2012, 48, 4770–4772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).(a) Zhang X-F; Yang XJ Phys. Chem. B 2013, 117, 9050–9055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Hahn U; Setaro F; Ragàs X; Gray-Weale A; Nonell S; Torres T Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys 2011, 13, 3385–3393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Ventura B; Marconi G; Bröring M; Krüger R; Flamigni L New. J. Chem 2009, 33, 428–438. [Google Scholar]; (d) Fukuzumi S; Ohkubo K; Zheng X; Chen Y; Pandey RK; Zhan R; Kadish KM; J. Phys. Chem. B 2008, 112, 2738–2746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Theillet F-X; Binolfi A; Frembgen-Kesner T; Hingorani K; Sarkar M; Kyne C; Li C; Gierasch L; Pielak GJ; Elcock AH; Gershenson A; Selenko P Chem. Rev 2014, 114, 6661–6714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Signore G; Abbandonato G; Storti B; Stöckl M; Subramaniam V; Bizzarri R Chem. Commun 2013, 49, 1723–1725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Cuervo A; Dans PD; Carrascosa JL; Orozco M; Gomila G; Fumagalli L Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 2014, 111, E3624–E3639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Sunahara H; Urano Y; Kojima H; Nagano TJ Am. Chem. Soc 2007, 107, 5597–5604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).(a) Jiang N; Fan J; Xu F; Peng X; Mu H; Wang J; Xiong X; Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2015, 54, 2510–2514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Xiao H.; Li P; Zhang W; Tang B. Chem. Sci 2016, 7, 1588–1593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).(a) Reichardt C Chem. Rev 1994, 94, 2319–2358. [Google Scholar]; Representative examples of near-IR polarity-responsive fluorophores:; (b) Kim D;..Moon H; Baik SH Singha S; Jun YW; Wang T; Kim KH; Park BS. Jung J; Mook-Jung I; Ahn KH. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2015, 137, 6781–6789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Karpenko IA; Collot M; Richert L; Valencia C; Villa P; Mély Y; Hibert M; Bonnet D; Klymchenko AS J. Am. Chem. Soc 2015, 137, 405–412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Berezin MY; Lee H; Akers W; Achilefu S Biophys. J 2007, 93, 2892–2899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Yang E; Kirmaier C; Krayer M; Taniguchi M; Kim H-J; Diers JR; Bocian DF; Lindsey JS; Holten DJ Phys. Chem. B 2011, 115, 10801–10816, and references cited therein. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).(a) Grin MA; Mironov AF; Shtil AA Anti-Cancer Agents Med. Chem 2008, 8, 683–697. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Silva EFF; Serpa C; Dabrowski JM; Monteiro CJP; Formosinho SJ; Stochel G; Urbanska K; Simões S; Pereira MM; Arnaut L Chem. Eur. J 2010, 16, 9273–9286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Yang E; Diers JR; Huang Y-Y; Hamblin MR; Lindsey JS; Bocian DF; Holten D Photochem. Photobiol 2013, 89, 605–618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Riyad YM; Naumov S; Schastak S; Griebel J; Kahnt A; Haupl T; Neuhaus J; Abel B; Hermann RJ Phys. Chem. B 2014, 118, 11646–11658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Cao W; Ng KK; Corbin I; Zhang Z; Ding L; Chen J; Zheng G Bioconjugate Chem. 2009, 20, 2023–2031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Liu TWB; Chen J; Burgess L; Cao W; Shi J; Wilson BC; Zheng G; Theranostics, 2011, 1, 354–362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Harada T; Sano K; Sato K; Watanabe R; Yu Z; Hanaoka H; Nakajima T; Choyke PL; Ptaszek M; Kabayashi H Bioconjugate Chem 2014. 25, 362–369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Yu Z; Pancholi C; Bhagavathy GV; Kang HS; Nguyen JK; Ptaszek MJ Org. Chem 2014, 79, 7910–385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Kang HS; Esemoto NN; Diers J; Niedzwiedzki D; Greco J; Akhigbe J; Yu Z; Pancholi C; Viswanathan BG, ; Nguyen JK; Kirmaier C.; Birge R; Ptaszek M; Holten D; Bocian DF J. Phys. Chem. A, 2016, 120, 379–385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Krayer M; Ptaszek M; Kim H-J; Meneely KR; Fan D; Secor K; Lindsey JS J. Org. Chem 2010, 75, 1016–1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).During the preparation of this manuscript, application of the analogous strategy for synthesis of chlorin dyads has been reported:; Xiong R.; Arkhypchuk AI; Kovacs D; Orthaber A; Borbas KE Chem. Comm 2016, DOI: 10.1039/c6cc00 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Ouyang Q; Yan K-Q; Zhu Y-Z; Zhang CH; Liu J-Z; Chen C; Zheng J-Y Org. Lett 2012, 14, 2746–2749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Cho S; Yoon M-C; Lim JM; Kim P; Aratani N; Nakamura Y; Ikeda T; Osuka A; Kim DJ Phys. Chem. B 2009, 113, 10619–10627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Bacteriochlorins can photosensitize both 1O2 and O2−., depending on their exact structures.12 We confirmed that BC1–4 photosensitize 1O2 (by determining luminescence at 1270 nm); however, we did not make any efforts to determine whether or not any of the bacteriochlorins examined here photosensitizes O2-. [Google Scholar]

- (21).(a) Spiller W; Kliesch H; Wöhrle D; Hackbarth S; Roder B; Schnurpfeil G. J. Porphyrins Phthalocyanines, 1998, 2, 145–158. [Google Scholar]; (b) Gomes A; Fernandes E; Lima JL F. C. J. Biochem. Biophys. Methods 2005, 65, 45–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Turro NJ; Ramamurthy V; Scaiano JC 2010. Modern molecular photochemistry of organic molecules. University Science Books; Sausalito, CA; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- (23).Redmond RW; Gamlin JN Photochem. Photobiol 1999, 70, 391–475. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Lissi EA; Encinas MV; Lemp E; Rublo MA Chem. Rev 1993, 93, 699–723. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.