Visual Abstract

Keywords: fluid overload, bioelectrical impedance analysis, fluid control, short-term outcome, Control Groups, Cardiovascular Diseases, Electric Impedance, Body Water, Survival Rate, peritoneal dialysis, dialysis, Water-Electrolyte Imbalance, Maintenance, diabetes mellitus

Abstract

Background and objectives

Bioelectrical impedance analysis (BIA) devices can help assess volume overload in patients receiving maintenance peritoneal dialysis. However, the effects of BIA on the short-term hard end points of peritoneal dialysis lack consistency. This study aimed to test whether BIA-guided fluid management could improve short-term outcomes in patients on peritoneal dialysis.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements

A single-center, open-labeled, randomized, controlled trial was conducted. Patients on prevalent peritoneal dialysis with volume overload were recruited from July 1, 2013 to March 30, 2014 and followed for 1 year in the initial protocol. All participants with volume overload were 1:1 randomized to the BIA-guided arm (BIA and traditional clinical methods) and control arm (only traditional clinical methods). The primary end point was all-cause mortality and secondary end points were cardiovascular disease mortality and technique survival.

Results

A total of 240 patients (mean age, 49 years; men, 51%; diabetic, 21%, 120 per group) were enrolled. After 1-year follow-up, 11(5%) patients died (three in BIA versus eight in control) and 21 patients were permanently transferred to hemodialysis (eight in BIA versus 13 in control). The rate of extracellular water/total body water decline in the BIA group was significantly higher than that in the control group. The 1-year patient survival rates were 96% and 92% in BIA and control groups, respectively. No significant statistical differences were found between patients randomized to the BIA-guided or control arm in terms of patient survival, cardiovascular disease mortality, and technique survival (P>0.05).

Conclusions

Although BIA-guided fluid management improved the fluid overload status better than the traditional clinical method, no significant effect was found on 1-year patient survival and technique survival in patients on peritoneal dialysis.

Introduction

Volume overload, which is associated with hypertension, cardiovascular events, morbidity, and mortality (1), occurs more frequently in patients receiving maintenance peritoneal dialysis (PD) than those receiving hemodialysis (HD) (2–4). However, the surrogate clinical parameters used to routinely determine volume status, such as edema, body weight, and BP, are typically affected by vascular stiffness, cardiac dysfunction, and malnutrition, which render their interpretation inconclusive (5). Bioelectrical impedance analysis (BIA) devices have proven to be potentially helpful for the clinical assessment of fluid overload (5) in two observational studies of patients on PD (6,7) and one interventional study of patients on HD (8).

A prospective trial on patients on HD concluded that BIA is not inferior and possibly even better than clinical criteria for assessing dry weight and guiding ultrafiltration in patients on HD (9). A 12-month randomized, controlled trial (RCT) of 308 patients on PD in the United Kingdom and Shanghai, China, showed worsening extracellular water (ECW)-to-total body water (TBW) ratios in active patients and controls with anuria; thus routine use of longitudinal bioimpedence vector plots to improve the clinical management of fluid status was not supported. Moreover, the hard end point of overall survival was not investigated (10).This prospective RCT aimed to investigate the outcome of BIA devices on the clinical assessment and management of hydration status in patients on PD.

Materials and Methods

Study Design

This prospective, single-center, open-labeled RCT analyzed prevalent patients on stable PD in The First Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-sen University, who were recruited from July 1, 2013, to March 30, 2014, and followed up for 1 year on the initial protocol. This trial was registered in the clinical trials registry (http://www.clinicaltrials.gov, trial number: NCT02000128). According to data analysis by the end of the study, the follow-up duration was extended to 3 years, on December 31, 2017. The rationales were presented in statistical method. Ethical approval (number: [2012]303) was granted by the Ethics Committee of The First Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-sen University, and all patients provided written informed consent.

Participants

Adult patients receiving continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis treatment for ≥3 months were screened using the BIA device (InBody720; Biospace, Seoul, Korea). An ECW/TBW ratio ≥0.4 (suggested by the BIA device manufacturer) was used to define fluid overload for participant enrollment (11). The exclusion criteria were as follows: contraindications to BIA measurement (amputation, presence of a pacemaker or prosthesis, or inability to stand steadily for 3 minutes), concomitant dialysis modalities (PD and HD), severe heart failure (New York Heart Association Functional Classification class 4), acute complications (peritonitis, pulmonary infection, etc.), severe malnutrition (Subjective Global Assessment class C), malignant tumor, or pregnancy.

Enrollment and Randomization

Participants recruited from the outpatient section of the PD center were randomly assigned, in a 1:1 ratio, to the BIA group (fluid management guided by BIA plus traditional clinical methods) or control group (fluid management guided by only traditional clinical methods). Randomization was done by a statistician (Q.Z.) independently. A randomization sequence was generated by a separate statistician using SAS 9.2 software (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). Simple randomization was performed without using stratification and blocks. Physicians and investigators in the trial were blinded to randomization.

Study Outcomes

The primary end point was all-cause mortality. The secondary end points were cardiovascular disease (CVD) mortality and technique survival. In the primary analysis of patient outcome, all participants were followed up until they achieved the end point, were censored, or finished the study. Dropout was defined as patients who withdraw from the study subjectively, missed the prescribed visit for ≧3 times, nonadherence to prescribed treatment for >3 months, or pregnancy. Kidney transplantation, spontaneous recovery of kidney function, dropout, and transition to another PD center were coded as censored events. CVD included ischemic heart disease, stroke (cerebral infarction, cerebral hemorrhage, and transient cerebral ischemic attack), and peripheral artery diseases (12). Each CVD was diagnosed strictly according to the standardized criteria. Technique failure referred to a situation where a patient receiving PD switches to HD for >3 months, but excluding patients who died, underwent kidney transplantation, or kidney function recovery (13). Outcome events and causes of death were registered by experienced nephrologists who were blinded to group allocation and were not changed during the trial.

Hydration Status Measurements and Management

Multifrequency BIA measurements were performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions (11), in the morning, during a routine clinical visit, as previously described (14), and PD fluid was not drained from the abdomen after the report (15).

In the control group, fluid balance was determined or adjusted by traditional clinical measures, including body weight, BP, edema, signs and symptoms of chronic heart failure (chest congestion, palpitations, dyspnea on exertion, nocturnal paroxysmal dyspnea, and orthopnea), or hypovolemia (dizziness and orthostatic hypotension). In the BIA group, ECW/TBW <0.4 and aforementioned clinical assessments were used to determine fluid status. BIA participants underwent serial body composition measurements during every visit, whereas controls were measured only at enrollment and at study completion. Regardless of the group, those diagnosed with fluid overload, were required to follow their water reduction protocol and return within a month, whereas those with euvolemia were instructed to return every 3 months.

Standard management of fluid overload was performed by nephrologists with at least 10 years of experience on managing patients on PD. All patients with volume overload were asked to restrict salt (<5 g/d) (16) and water intake. For those with urine volume >200 ml/d, patients were prescribed diuretics to increase urine output before using dialysate with glucose concentration >1.5%. Diuretic (usually furosemide) dosage was gradually increased to a maximum of 200 mg/d. On this basis, more hypertonic dialysate, shortened night dwelling time, or intermittent PD was recommended for increased water removal. All participants underwent PD using the dialysis systems (Baxter Healthcare, Deerfield, IL). Automated PD and icodextrin were not used.

Sample Collection and Laboratory Analysis

Clinical manifestations, fluid status, medication, and PD prescription (PD modality, dosage, and dialysate glucose concentration) were evaluated during routine visits. All serum and dialysate biochemical parameters were measured using the AU5821–2 automatic biomedical analyzer (Beckman Coulter Life Sciences, Indianapolis, IN). N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) level was analyzed in plasma using an automatic electrochemiluminescence immunoassay and a COBAS 601 module (Roche, Basel, Switzerland), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The analytical sensitivity was 15 pg/ml (reportable range is 20–45,000 pg/ml). Cardiac investigations (cardiac symptom, New York Heart Association classification, NT-proBNP, and echocardiography) were performed regularly.

Both 24-hour urine and PD effluent were collected at the same time each day to calculate urea clearance (weekly) (Kt/V), creatinine clearance, normalized protein clearance rate, and measured GFR, which was calculated as the average 24-hour kidney creatinine and urea clearance and normalized to 1.73 m2 body surface area using Adequest 2.0 software (Baxter Healthcare).

Statistical Analyses

The estimated sample size was 240 to provide the trial with 90% power to detect an absolute difference of 10% points in all-cause mortality at 1-year follow-up from an estimated baseline mortality of 85%, at an α level of 0.05 (17–21). This calculation allowed for a withdrawal rate and follow-up loss of 10% (Supplemental Appendix 1).

Data were presented as mean±SD for normally distributed continuous variables, median and interquartile range for skewed continuous variables, and frequencies and percentages for categorical variables. One-way ANOVA was performed for comparing normally distributed continuous variables and Mann–Whitney U test for non-normally distributed continuous variables. The chi-squared test was used for categorical variables. Primary efficacy analyses were on the basis of the intent-to-treat approach. Patient survival and technique survival were calculated using the Kaplan–Meier method, and differences between different groups were assessed by log-rank tests. Considering patients transferred to other modalities as censoring (competing end points), the Fine and Gray proportional subhazards model was used to create a competing risk model (Supplemental Appendix 2) (22).

The rate of ECW/TBW decline over time was calculated with a mixed effect model of linear growth for each patient, using SAS 9.2 (23). The linear model of the BIA group was fitted on the basis of repeated BIA measurements every 1–3 months, whereas the control group was on the basis of BIA data collected at the beginning and end of the study. Patients who dropped out were still included in the analysis. A two-sided P<0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 16.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY), R 3.6.1 (Bell Laboratories, Murray Hill, NJ; https://cran.r-project.org/bin/windows/base/old/3.6.1/), and SAS 9.2.

Results

Baseline Characteristics

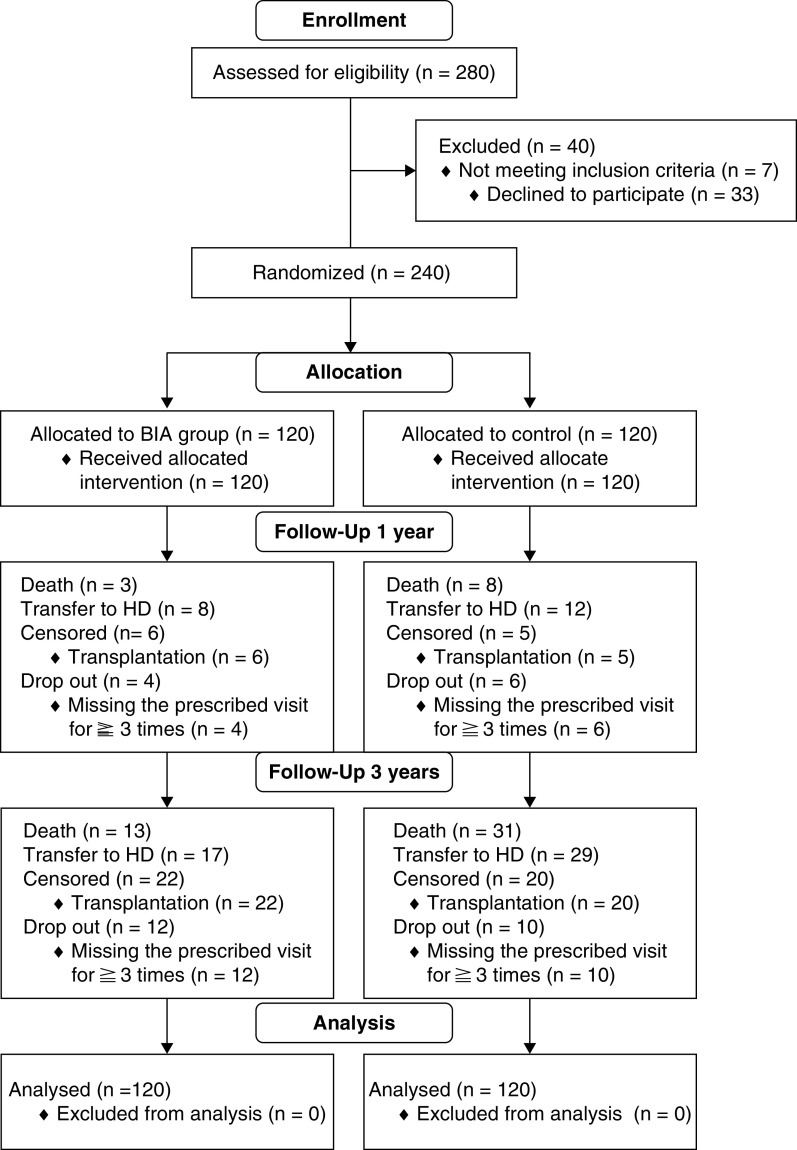

Of the 280 patients screened who were receiving continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis, 40 patients were excluded; 240 eligible patients were enrolled and randomized into the BIA (n=120) or control group (n=120). Baseline characteristics of the two groups were shown in Table 1. The overall median follow-up time was 32 (interquartile range, 1–53) months, including 1 year on the initial protocol and 2 years on extended follow-up. Recruitment, randomization, end point, and dropout were summarized in the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials diagram (Figure 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the BIA group and control group

| Characteristics | All, n=240 | Control, n=120 | BIA, n=120 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male, n (%) | 122 (51) | 663 (53) | 59 (49) |

| Age, yr | 49±15 | 50±16 | 48±14 |

| Vintage, mo | 32 (17–50) | 31 (16–49) | 32 (16–50) |

| Primary disease of ESKD, n (%) | |||

| Chronic glomerular nephritis | 136 (56) | 70 (58) | 66 (55) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 51 (21) | 25 (21) | 26 (22) |

| Hypertension | 16 (7) | 9 (8) | 7 (6) |

| SLE | 6 (3) | 3 (3) | 3 (3) |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 22.1±3.1 | 22.4±3.2 | 21.8±3.0 |

| Systolic BP, mm Hg | 142±20 | 142±21 | 142±19 |

| Diastolic BP, mm Hg | 83±13 | 83±14 | 84±12 |

| Antihypertensive medication use, n (%) | |||

| No use | 30 (13) | 17 (14) | 13 (11) |

| Single use | 16 (6) | 8 (6) | 8 (7) |

| Two combinations | 41 (17) | 20 (17) | 21 (17) |

| Three combinations | 76 (32) | 37 (31) | 39 (32) |

| Four combinations | 63 (26) | 32 (27) | 31 (26) |

| Five combinations | 14 (6) | 6 (5) | 8 (7) |

| History of MI, n (%) | 18 (7.5) | 10 (8.3) | 8 (6.7) |

| History of stroke, n (%) | 10 (4.2) | 5 (4.2) | 5 (4.2) |

| Comorbidity score | 3 (2–5) | 3 (2–6) | 3 (2–5) |

| ECOG activity index, n (%) | |||

| 1 | 3 (1) | 1 (1) | 2 (2) |

| 2 | 138 (58) | 68 (57) | 70 (58) |

| 3 | 81 (34) | 39 (32) | 42 (35) |

| 4 | 18 (7) | 12 (10) | 6 (5) |

| NYHA classification, n (%) | 104/117/19 | 48/60/12 | 56/57/7 |

| 1 | 104 (43) | 48 (40) | 56 (47) |

| 2 | 117 (49) | 60 (50) | 57 (47) |

| 3 | 19 (8) | 12 (10) | 7 (6) |

| Measured GFR, ml/min per 1.73 m2 | 0.9 (0.1–2.4) | 0.8 (0.1–2.4) | 0.9 (0.1–2.5) |

| Residual urine volume, ml/24 h | 250 (0–650) | 200 (0–550) | 300 (25–700) |

| Hemoglobin, g/dl | 10.8±1.9 | 10.7±2.0 | 10.9±1.8 |

| Serum albumin, g/dl | 3.8±0.4 | 3.7±0.4 | 3.8±0.4 |

| Prealbumin, mg/dl | 375±87 | 372±86 | 372±90 |

| Uric acid, mg/dl | 4.6±0.9 | 4.5±0.9 | 4.6±0.9 |

| iPTH, pg/ml | 412 (248–703) | 411 (266–665) | 413 (233–733) |

| hs-CRP, mg/L | 1.6 (0.6–4.5) | 1.6 (0.6–4.5) | 1.5 (0.5–4.8) |

| NT-proBNP, pg/ml | 4161 (1743–14536) | 5167 (1840–18700) | 4066 (1535–11246) |

| PD dosage, L/d | 8 (8–8) | 8 (8–8) | 8 (8–8) |

| Ultrafiltration volume, ml/24 h | 450 (200–800) | 500 (200–800) | 400 (200–800) |

| Total Kt/V | 2.3±0.6 | 2.2±0.6 | 2.3±0.6 |

| Total creatinine clearance, L/w | 65±22 | 65±23 | 65±22 |

| nPCR | 0.9±0.2 | 0.8±0.2 | 0.9±0.2 |

| Peritoneal transport type, n (%) (n=212) | |||

| High and high-average transport type | 137 (65) | 72 (71) | 65 (59) |

| Low and low-average transport type | 75 (35) | 30 (29) | 45 (41) |

| Total body water, L | 37.5±7.7 | 37.9±7.7 | 37.0±7.6 |

| Extracellular water, L | 15.4±3.3 | 15.6±3.2 | 15.2±3.4 |

| Intracellular water, L | 22.1±4.6 | 22.4±4.4 | 21.7±4.9 |

| Extracellular water//total body water, ×10e2 | 40.6 (40.3–41.3) | 40.8 (40.2–41.4) | 40.5 (40.1–41.3) |

Values for continuous variables are given as mean±SD or median (interquartile range). BIA, bioelectrical impedance analysis; BMI, body mass index; MI, myocardial infarction; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; NYHA, New York Heart Association; iPTH, intact parathyroid hormone; hs-CRP, high-sensitive C-reactive protein; NT-proBNP, N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide; PD, peritoneal dialysis; nPCR, normalized protein clearance rate.

Figure 1.

Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials diagram. BIA, bioelectrical impedance analysis; HD, hemodialysis.

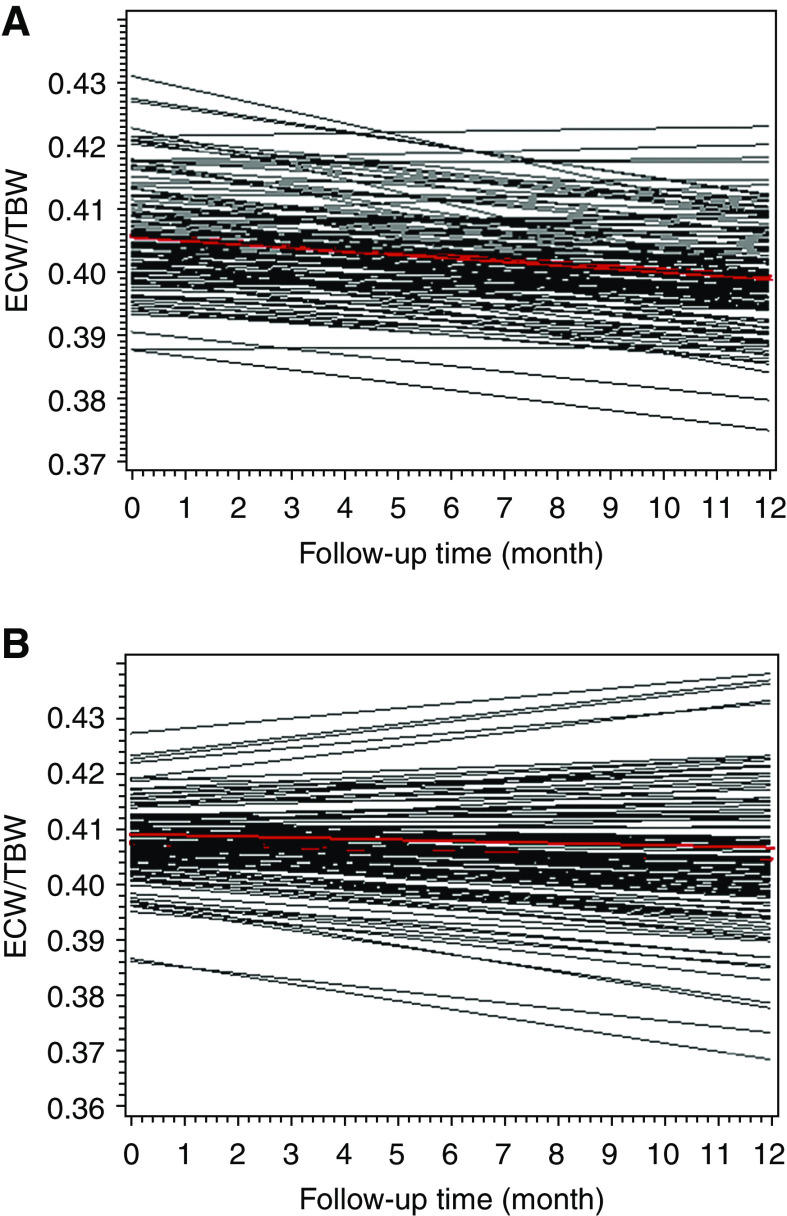

Rate of ECW/TBW Decline after 1-Year Intervention

A significantly lower ECW and ECW/TBW ratio were found in the BIA group than in the control group (Table 2). To better estimate the effect of BIA-guided fluid management on fluid control, the decline rates of the ECW/TBW ratio by 0.001 unit per month in the two groups were compared (Figure 2, A and B): the rate of ECW/TBW decline in the BIA group was significantly higher than that in the control group (−0.00054 versus −0.00024; P=0.04). After 1 year, 55% (BIA group) and 35% (control group) of the patients achieved the fluid control target (ECW/TBW <0.4; P=0.01).

Table 2.

Comparisons of serum parameters and clinical assessments of BIA group with control group by 1-year intervention

| Variables | Total, n=175 | Control, n=84 | BIA, n=91 | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Extracellular water, L | 15.1±3.2 | 15.6±3.1 | 14.5±3.2 | 0.04 |

| Extracellular water/total body water, ×10e2 | 40.1 (39.3–41.0) | 40.4 (39.3–41.3) | 40.0 (39.3–40.7) | 0.03 |

| Systolic BP, mm Hg | 140±15 | 142±18 | 139±14 | 0.14 |

| Diastolic BP, mm Hg | 84±13 | 84±14 | 84±13 | 0.43 |

| Change of serum calcium, mg/dl, ×10e3 | −0.3 (−1.5 to 1.2) | −0.3 (−1.5 to 1.3) | −0.3 (−1.6 to 1.1) | 0.51 |

| Change of serum phosphorus, mg/dl, ×10e3) | 0.9 (−2.1 to 4.0) | 1.5 (−0.9 to 4) | 0.4 (−3.4 to 3.6) | 0.36 |

| Change of iPTH, pg/ml | −62 (−219 to 67) | −93 (−277 to 110) | −55 (−206 to 63) | 0.39 |

| Change of hs-CRP, mg/L | 0.35 (0.81–3.79) | −0.1 (−1.8 to 1.1) | 0.9 (−0.3 to 5.1) | 0.04 |

| Change of hemoglobin, g/dl | 0.2±1.8 | 0.2±1.9 | 0.3±1.8 | 0.72 |

| Change of serum albumin, g/dl | −0.2±0.5 | −0.3±0.3 | −0.1±0.5 | 0.01 |

| Change of prealbumin, mg/dl | −22 (−52 to 37) | −14 (−36 to 46) | −32 (−76 to 20) | 0.29 |

| SGA, n (%) | 0.001 | |||

| 1 | 116 (73.41) | 45 (60.00) | 71 (85.57) | |

| 2 | 39 (24.68) | 29 (38.66) | 10 (12.04) | |

| 3 | 3 (1.89) | 1 (1.33) | 2 (2.40) | |

| Change of total Kt/V | −1.2±0.1 | −1.2±0.1 | −1.2±0.1 | 0.99 |

| Change of total Ccr, L/w | −7.1±1.9 | −8.3±2.8 | −5.9±2.4 | 0.53 |

| Change of residual urine, ml/24 h | −100 (−300 to 0) | −100 (−350 to 0) | −275 (−560 to −90) | 0.69 |

| Change of mGFR, ml/min per 1.73 m2 | −0.3 (−1 to 0) | −0.3 (−1.0 to −0.1) | −0.2 (−0.9 to 0) | 0.53 |

Values for continuous variables are given as mean±SD or median (interquartile range). Data were collected from patients who have completed the trial (n=175), whereas data from those who died, transplanted, transferred to HD, or withdrew within 1 year were unable to be collected. BIA, bioelectrical impedance analysis; iPTH, intact parathyroid hormone; hs-CRP, high-sensitive C-reactive protein; SGA, Subjective Global Assessment (1, grade A; 2, grade B; 3, grade C); Ccr, creatinine clearance; mGFR, measured GFR.

Figure 2.

The decline rate of ECW/TBW (per month) was faster in the BIA group than in the control group. (A) The decline rate of ECW/TBW in the BIA group. The fixed effect over time was −0.00054 (P<0.001). (B) The decline rate of ECW/TBW in the control group. The fixed effect over time was −0.00024 (P=0.03). The decline rate of ECW/TBW over time was calculated by a random intercept and slope model of linear growth. The red lines represent the fitted mean change of ECW/TBW over 1 year. ECW/TBW, extracellular water-to-total body water ratio.

Changes in Clinical Assessments and Laboratory Test Items on 1-Year Intervention

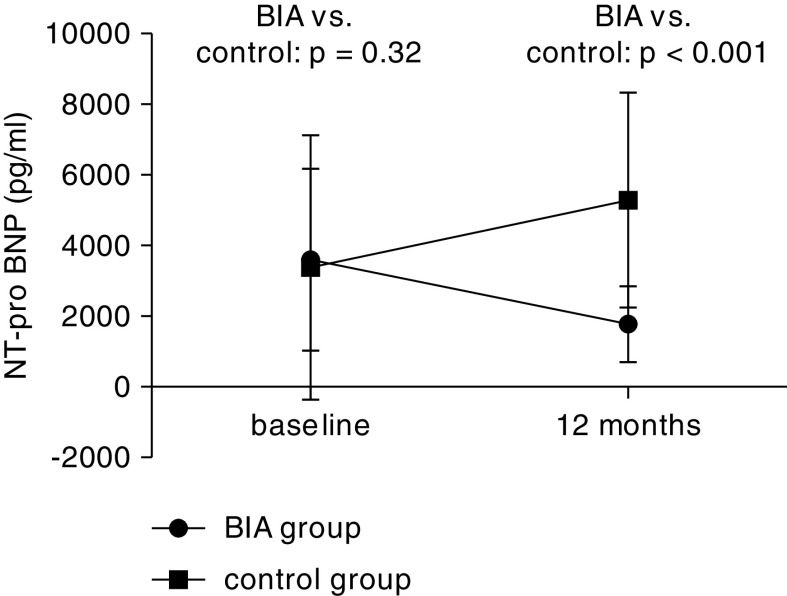

Compared with baseline data, the serum NT-proBNP level decreased from 4066 (IQR, 1535–11,246) pg/ml to 2029 (IQR, 1006–5965) pg/ml (P=0.01) in the BIA group and was significantly lower than that in the control (P<0.001; Figure 3). ECW and ECW/TBW ratio were lower in the BIA group versus control group. Increase in serum albumin level and decrease in C-reactive protein level and Subjective Global Assessment class in the BIA group were statistically significant compared with that of the control group. No statistical differences were found in BP, change of hemoglobin, serum calcium and phosphorus, intact parathyroid hormone, Kt/V and creatinine clearance, residual urine volume, and measured GFR between the two groups (Table 2).

Figure 3.

Mean changes of NT-proBNP from baseline to 1-year follow-up in BIA group and control group (patient number at baseline was 240). Data at 12 months were collected from patients who have completed the trial (n=175), whereas data from those who died, transplanted, transferred to HD, or withdrew within 1 year were unable to be collected. NT-proBNP, N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide.

One-Year Primary and Secondary Outcomes

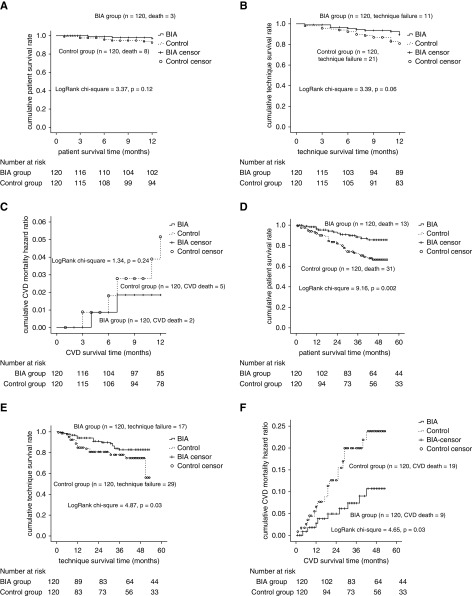

After 1-year follow-up, 11 (5%) patients died (three in BIA group versus eight in control group). The overall patient survival was not statistically different between the two groups (log-rank chi-squared =3.37; P=0.12; Figure 4A). Competing risk regression of overall survival between the two groups showed no statistical difference. (subdistribution hazard ratio [sHR], 0.89; 95% confidence interval [95% CI], 0.12 to 6.49) (Supplemental Figure 1). The causes of death included CVD (n=8, two BIA patients and six controls), lymphoma (n=1, BIA group) and catheter-related infection and pulmonary infection (n=2, control group). Cardiovascular mortality analyzed by Kaplan–Meier method also showed no statistical difference between the two groups (log-rank chi-squared =1.34; P=0.24; Figure 4C). CVD and adverse events had no statistical difference between the two groups (Table 3).

Figure 4.

Survival of BIA arm and control arm. (A) Patient survival by the end of 12-month follow-up. (B) PD technique survival by the end of 12-month follow-up. (C) Cardiovascular disease mortality by the end of 12-month follow-up. (D) Patient survival by the end of 3-year follow-up. (E) Technique survival by the end of 3-year follow-up. (F) Cardiovascular disease (CVD) mortality by the end of 3-year follow-up.

Table 3.

Cardiovascular disease events and adverse event during 1-year observation period

| Events | Control, n=120 | BIA, n=120 | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiovascular disease events, n=31 | |||

| Congestive heart failure, n=22 | 13 (10%) | 9 (8%) | 0.42 |

| Myocardial infarction, n=1 | 0 | 1 (1%) | 0.54 |

| Angina pectoris, n=2 | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | 0.94 |

| Cerebral infarction/hemorrhage, n=4 | 2 (2%) | 2 (2%) | 0.96 |

| Peripheral vascular disease, n=2 | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | 0.95 |

| Adverse event | |||

| Hypotension, n=0 | 0 | 0 | — |

Log-rank test was used to compare the events between two groups. BIA, bioelectrical impedance analysis; —, not applicable.

Overall, 21 patients (eight BIA patients and 13 controls) were permanently transferred to HD during 1-year follow-up. The technique survival rates were 91% and 83% in the BIA and control groups, respectively (log rank chi-squared =3.39; P=0.06) (Figure 4B). Competing risk regression of technique survival showed no statistical difference. (sHR, 0.44; 95% CI, 0.16 to 1.18) (Supplemental Figure 2).

Exploratory Outcome of Extended 3-Year Follow-Up

After 3-year follow-up, 87 participants (56 BIA patients and 31 controls) were still included in the cohort. During the follow-up period, 44 (18%) patients died (13 [11%] BIA patients and 31 [26%] controls). Causes of death included CVD (n=28), peritonitis (n=7), pulmonary infection (n=4), malignant tumor (n=2), suicide (n=1), and giving up treatment (n=2). Forty six patients were permanently transferred to HD (17 BIA patients and 29 controls). Moreover, 12 BIA patients and ten controls dropped out (P=0.65; Figure 1). In the BIA group, Kaplan–Meier analysis revealed 1-, 2-, and 3-year cumulative patient survival rates of 96%, 92%, and 87% respectively, whereas those in the control group were 92%, 82%, and 72%, respectively (log-rank chi-squared =9.16; P=0.002; Figure 4D). The Fine and Gray proportional subhazards model demonstrated that the risk of the primary outcome being death was lower for the BIA group than for the control group (sHR, 0.51; 95% CI, 0.26 to 0.99), although the groups exhibited no significant differences in other competing events (Supplemental Figure 3, Supplemental Table 3). The cumulative CVD 3-year mortality was significantly lower in the BIA group than the control group (10% versus 22%; log-rank chi-squared =4.65; P=0.03; Figure 4F). The analysis on the per-protocol population (22 patients were excluded because of poor adherence to treatment regimen) (Supplemental Figures 4 and 5) was consistent with the previous results. The technique survival rate was 82% in the BIA group and 59% in the control group (log-rank chi-squared =4.87; P=0.03; Figure 4E). However, this result was not confirmed by the competing risk of technique failure using the Fine and Gray proportional subhazards model, either by univariable analysis (sHR, 0.62; 95% CI, 0.35 to 1.11) or multivariable analysis (sHR, 0.59; 95% CI, 0.32 to 1.10) (Supplemental Figure 6, Supplemental Table 4).

Discussion

Our study demonstrated that the BIA-guided fluid management presented no significant effect on overall survival and technique survival. However, volume overload control presented as NT-proBNP and decline of longitudinal ECW/TBW ratio were more favorable in the BIA-guided group. These findings suggested that BIA combined with clinical methods was not superior to the clinical methods on patient outcomes on the basis of 1-year intervention.

BIA has been extensively studied and has become a promising technique for routine monitoring of fluid status and nutrition in patients receiving dialysis (5,24,25). An RCT including patients on HD showed that the all-cause mortality rate of patients managed with BIA guidance was lower than that of controls after 2.5 years of follow-up (26,27). In an observational cohort study including PD and HD populations, the extracellular fluid volume-to-TBW ratio was a predictor of both all-cause and cardiovascular mortality, independent of dialysis modality and the presence of other known clinical and biochemical risk factors (7). In our predesigned 1-year intervention, we did not find any improvement on the prognosis of patients on PD. Notably, considering the insufficient observation time, we extended the study period to 3 years after obtaining informed consent from participants. The exploratory results demonstrated improved hard outcomes in terms of patient survival and non-CVD survival in the BIA group. Because this trial was not predesigned for a 3-year follow-up, the results of our exploratory analyses should be further investigated in studies with a longer follow-up period.

Unlike the findings of Tan et al. (10), the control of fluid overload in our study was more effective and quicker by BIA-guided fluid management. The advantage of the BIA method lies in the quantification of excess ECW in patients on dialysis. Meanwhile, the results of body composition monitoring (muscle, fat, and protein) could be combined with fluid data to identify the reasons for body weight gain. However, under certain conditions, such as malnutrition and loss of cell mass (intracellular water), the ECW/TBW ratio of patients was >0.4. These patients should not be managed by increasing ultrafiltration, as this may result in dehydration or insufficient perfusion. Therefore, BIA should be used as an adjunct to clinical methods to obtain accurate judgment of the hydration status. The Patient Outcomes in Dialysis study, which compared hydration measurement results using BIA and traditional clinical methods in 1092 patients receiving incident PD from 135 PD centers, also showed that BIA should be combined with traditional clinical methods to judge the hydration status (28). It is noted that the algorithms to estimate body composition vary with different BCM devices used. This study used the InBody720 device in which patient’s weight and PD fluid weight were not included in its algorithm. Davenport (29) found that measurements with 720, such as ECW, intracellular water, and trunk ECW/TBW ratio, were all higher when dialysate was full rather than empty, whereas segmental ECW/TBW ratio was only different for the trunk. This is a study limitation.

Notably, a relatively high proportion of patients did not reach normovolemic status (45% in the BIA group and 64% in the control group) by 1-year intervention. Compared with patients on HD, those on PD have difficulty reaching and maintaining their dry body weight because of the dialysis modality per se. Firstly, the ultrafiltration of a patient on PD is mainly dependent on the peritoneal transport feature itself, although it can be adjusted by dwell time, dialysis dose, and osmotic pressure of PD solution. Secondly, adherence to doctor’s advices varies greatly among patients, resulting in difference in sodium restriction, water intake, and dialysis prescription adherence. Thirdly, icodextrin and automatic PD were unavailable in the study population. Thus, longitudinal application of BIA along with clinical information may help identify the fluid overload problem; however, advanced therapeutic approaches in decreasing volume expansion are more required to improve the outcomes of the PD population.

Our previous investigation of the relationship between overhydration and residual kidney function (RKF) demonstrated that overhydration could lead to a decline in RKF per se (30). A recent study from Korea showed that BIA-guided fluid control did not affect RKF of patients on PD (31). In our cohort, the baseline median urine volume was only 250 ml and 88 (36%) patients had anuria. After 1-year follow-up, the median urine volume decreased to 100 ml and 110 (63%) patients had anuria, with no difference between groups. Notably, this trial was not designed to investigate the change in RKF during the volume control process, so we could not assert that BIA has any effect on preservation of RKF. Nonetheless, intravascular volume depletion should be avoided to better preserve RKF.

There are several limitations of this study. First, the ratio of ECW/TBW ≥0.4 was used to define overhydration, which was on the basis of a fluid status measurement in 6520 healthy Koreans, and may not be generalizable to Chinese patients on dialysis. Moreover, we did not define the lower limit of the hydration status on the BIA instrument, which makes it incapable of specifically indicating volume deficiency status. Second, with regard to the sample size, we underestimated the 1-year patient survival and the number of events for the primary end point. Finally, the analysis of change in serum parameters and clinical assessments (Table 3) was on the basis of data of patients who were still alive and had not quit the study in a year, which inevitably induced an issue of missing value/dropout.

In summary, our results from a 1-year cohort study demonstrate that BIA-guided fluid management was more effective to achieve fluid balance than traditional clinical methods alone, but there was no difference in the outcomes in terms of patient survival, technique survival, and CVD mortality. However, a larger study with a longer follow-up period is warranted to confirm our results.

Disclosures

Ms. Cao, Dr. Chen, Dr. Guo, Ms. Lin, Dr. Tian, Dr. Yang, Dr. Ye, Ms. Yi, Dr. Yu, and Dr. Zhou have nothing to disclose.

Funding

This work was supported by National Key Research and Development program grant 2016YFC0906101, Guangdong Science Foundation of China grants 2017A050503003 and 2017B020227006, Guangzhou Committee of Science and Technology, China grant 201704020167, Science and Technology Planning Project of Guangdong Province of China grants A2018353 and A2018042, the First-Class Discipline Construction Founded Project of NingXia Medical University and School of Clinical Medicine grant NXYLXK2017A05, and Natural Science Foundation of NingXia Province grant NZ16164.

Supplementary Material

Data Sharing Statement

All individual participant data in this manuscript are available on request (including data dictionaries). Individual participant data reported in this article (text, tables, figures, and appendices) will be shared after deidentification. The study protocol is available at http://www.clinicaltrials.gov (trial number: NCT02000128). The statistical analysis plan is available in the Supplemental Material. Data sharing will be available beginning 3 months and ending 12 months after article publication, and data can be used for individual participant data meta-analysis. Investigators whose proposed use of the data has been approved by an independent review committee will have access to the data. Proposals for data sharing should be directed to yuxq@mail.sysu.edu.cn, and data requestors will need to sign a data access agreement to gain access. After 12 months, the data will be available at the Department of Nephrology, The First Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-sen University, Guangzhou, Guangdong, China, and stored as a .csv file.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the collaborative team in our peritoneal dialysis center and support from all participants in the study.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

See related editorial, “The Elusive Promise of Bioimpedance in Fluid Management of Patients Undergoing Dialysis,” on pages 597–599.

Supplemental Material

This article contains the following supplemental material online at http://cjasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.2215/CJN.06480619/-/DCSupplemental.

Supplemental Table 1. Competing risk regression of 1-year overall survival between patients on BIA or control group.

Supplemental Table 2. Competing risk regression of 1-year technique survival between patients on BIA or control group.

Supplemental Table 3. Competing risk regression of 3-year overall survival between patients on BIA or control group.

Supplemental Table 4. Competing regression of 3-year technique survival between patients on BIA or control group.

Supplemental Table 5. Clinical characteristics of patients on different outcomes at 1-year follow-up.

Supplemental Table 6. Clinical characteristics of patients on different outcomes at 3-year follow-up.

Supplemental Table 7. Cox regression analysis of groups associated with all-cause death and technique failure.

Supplemental Figure 1. Competing risk analysis on 1-year survival between the BIA and control group.

Supplemental Figure 2. Competing risk analysis on 1-year technique survival between the BIA and control group.

Supplemental Figure 3. Competing risk analysis on 3-year survival between the BIA and control group.

Supplemental Figure 4. Comparison of the BIA group and the control group in terms of patient survival based on per-protocol population.

Supplemental Figure 5. Comparison of the BIA group and the control group in terms of technique survival based on per-protocol population.

Supplemental Figure 6. Competing risk regression of 3-year technique survival between the BIA and control group.

Supplemental Figure 7. Comparison of the decline rate of the ECW/TBW ratio by 0.001 unit (per month) in the BIA and control group through 1-year intervention after multiple imputation in the (A) BIA group and (B) control group.

Supplemental Appendix 1. Sample size calculation and prolonging follow-up time explanation.

Supplemental Appendix 2. Instruction of competing risk model by Fine and Gray’s proportional subhazards model.

References

- 1.Tonelli M, Wiebe N, Culleton B, House A, Rabbat C, Fok M, McAlister F, Garg AX: Chronic kidney disease and mortality risk: A systematic review. J Am Soc Nephrol 17: 2034–2047, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Enia G, Mallamaci F, Benedetto FA, Panuccio V, Parlongo S, Cutrupi S, Giacone G, Cottini E, Tripepi G, Malatino LS, Zoccali C: Long-term CAPD patients are volume expanded and display more severe left ventricular hypertrophy than haemodialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant 16: 1459–1464, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Konings CJ, Kooman JP, Schonck M, Cox-Reijven PL, van Kreel B, Gladziwa U, Wirtz J, Gerlag PG, Hoorntje SJ, Wolters J, Heidendal GA, van der Sande FM, Leunissen KM: Assessment of fluid status in peritoneal dialysis patients. Perit Dial Int 22: 683–692, 2002 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Devolder I, Verleysen A, Vijt D, Vanholder R, Van Biesen W: Body composition, hydration, and related parameters in hemodialysis versus peritoneal dialysis patients. Perit Dial Int 30: 208–214, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davies SJ, Davenport A: The role of bioimpedance and biomarkers in helping to aid clinical decision-making of volume assessments in dialysis patients. Kidney Int 86: 489–496, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Koh KH, Wong HS, Go KW, Morad Z: Normalized bioimpedance indices are better predictors of outcome in peritoneal dialysis patients. Perit Dial Int 31: 574–582, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Paniagua R, Ventura MD, Avila-Díaz M, Hinojosa-Heredia H, Méndez-Durán A, Cueto-Manzano A, Cisneros A, Ramos A, Madonia-Juseino C, Belio-Caro F, García-Contreras F, Trinidad-Ramos P, Vázquez R, Ilabaca B, Alcántara G, Amato D: NT-proBNP, fluid volume overload and dialysis modality are independent predictors of mortality in ESRD patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant 25: 551–557, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Onofriescu M, Hogas S, Voroneanu L, Apetrii M, Nistor I, Kanbay M, Covic AC: Bioimpedance-guided fluid management in maintenance hemodialysis: A pilot randomized controlled trial. Am J Kidney Dis 64: 111–118, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Onofriescu M, Mardare NG, Segall L, Voroneanu L, Cuşai C, Hogaş S, Ardeleanu S, Nistor I, Prisadă OV, Sascău R, Covic A: Randomized trial of bioelectrical impedance analysis versus clinical criteria for guiding ultrafiltration in hemodialysis patients: Effects on blood pressure, hydration status, and arterial stiffness. Int Urol Nephrol 44: 583–591, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tan BK, Yu Z, Fang W, Lin A, Ni Z, Qian J, Woodrow G, Jenkins SB, Wilkie ME, Davies SJ: Longitudinal bioimpedance vector plots add little value to fluid management of peritoneal dialysis patients. Kidney Int 89: 487–497, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guo Q, Yi C, Li J, Wu X, Yang X, Yu X: Prevalence and risk factors of fluid overload in Southern Chinese continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis patients. PLoS One 8: e53294, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tendera M, Aboyans V, Bartelink ML, Baumgartner I, Clément D, Collet JP, Cremonesi A, De Carlo M, Erbel R, Fowkes FG, Heras M, Kownator S, Minar E, Ostergren J, Poldermans D, Riambau V, Roffi M, Röther J, Sievert H, van Sambeek M, Zeller T; European Stroke Organisation; ESC Committee for Practice Guidelines: ESC Guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of peripheral artery diseases: Document covering atherosclerotic disease of extracranial carotid and vertebral, mesenteric, renal, upper and lower extremity arteries: The Task Force on the Diagnosis and Treatment of Peripheral Artery Diseases of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J 32: 2851–2906, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Blake PG: Trends in patient and technique survival in peritoneal dialysis and strategies: How are we doing and how can we do better? Adv Ren Replace Ther 7: 324–337, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moissl UM, Wabel P, Chamney PW, Bosaeus I, Levin NW, Bosy-Westphal A, Korth O, Müller MJ, Ellegård L, Malmros V, Kaitwatcharachai C, Kuhlmann MK, Zhu F, Fuller NJ: Body fluid volume determination via body composition spectroscopy in health and disease. Physiol Meas 27: 921–933, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Davison SN, Jhangri GS, Jindal K, Pannu N: Comparison of volume overload with cycler-assisted versus continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 4: 1044–1050, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fouque D, Vennegoor M, ter Wee P, Wanner C, Basci A, Canaud B, Haage P, Konner K, Kooman J, Martin-Malo A, Pedrini L, Pizzarelli F, Tattersall J, Tordoir J, Vanholder R: EBPG guideline on nutrition. Int Urol Nephrol 22[Suppl 2]: ii45–ii87, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Keshaviah P, Collins AJ, Ma JZ, Churchill DN, Thorpe KE: Survival comparison between hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis based on matched doses of delivered therapy. J Am Soc Nephrol 13[Suppl 1]: S48–S52, 2002 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Abraham G, Kumar V, Nayak KS, Ravichandran R, Srinivasan G, Krishnamurthy M, Prasath AK, Kumar S, Thiagarajan T, Mathew M, Lesley N: Predictors of long-term survival on peritoneal dialysis in South India: A multicenter study. Perit Dial Int 30: 29–34, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yu X, Yang X: Peritoneal dialysis in China: Meeting the challenge of chronic kidney failure. Am J Kidney Dis 65: 147–151, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.El Khayat SS, Hallal K, Gharbi MB, Ramdani B: Fate of patients during the first year of dialysis. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl 24: 605–609, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li PK, Chow KM: Peritoneal dialysis-first policy made successful: Perspectives and actions. Am J Kidney Dis 62: 993–1005, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Austin PC, Fine JP: Practical recommendations for reporting Fine-Gray model analyses for competing risk data. Stat Med 36: 4391–4400, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Littell RC, Henry PR, Ammerman CB: Statistical analysis of repeated measures data using SAS procedures. J Anim Sci 76: 1216–1231, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baek SH, Oh KH, Kim S, Kim DK, Joo KW, Oh YK, Han BG, Chang JH, Chung W, Kim YS, Na KY: Control of fluid balance guided by body composition monitoring in patients on peritoneal dialysis (COMPASS): Study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials 15: 432, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Abbas SR, Zhu F, Levin NW: Bioimpedance can solve problems of fluid overload. J Ren Nutr 25: 234–237, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jones CH, Smye SW, Newstead CG, Will EJ, Davison AM: Extracellular fluid volume determined by bioelectric impedance and serum albumin in CAPD patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant 13: 393–397, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kraemer M, Rode C, Wizemann V: Detection limit of methods to assess fluid status changes in dialysis patients. Kidney Int 69: 1609–1620, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bedogni G, Malavolti M, Severi S, Poli M, Mussi C, Fantuzzi AL, Battistini N: Accuracy of an eight-point tactile-electrode impedance method in the assessment of total body water. Eur J Clin Nutr 56: 1143–1148, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Davenport A: Does peritoneal dialysate affect body composition assessments using multi-frequency bioimpedance in peritoneal dialysis patients? Eur J Clin Nutr 67: 223–225, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tian N, Guo Q, Zhou Q, Cao P, Hong L, Chen M, Yang X, Yu X: The impact of fluid overload and variation on residual renal function in peritoneal dialysis patient. PLoS One 11: e0153115, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yoon HE, Kwon YJ, Shin SJ, Lee SY, Lee S, Kim SH, Lee EY, Shin SK, Kim YS: Bioimpedance spectroscopy-guided fluid management in peritoneal dialysis patients with residual kidney function: A randomized controlled trial. Nephrology (Carlton) 24: 1279–1289, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.