Abstract

Background:

Syringic acid (SA) has long been used as traditional medicine and is known to have antioxidant, hepatoprotective, neuroprotective and anticancer effects. Studies regarding the anticancer effect of SA against squamous carcinoma cell (SCC)-25, human oral SCC (OSCC) line has not been studied.

Aim:

This study was aimed to evaluate the cytotoxic potentials of SA in SCC-25 cells.

Materials and Methods:

Cytotoxic effect of SA was determined by 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenylte trazolium bromide assay, using concentrations of 25 and 50 μM/mL for 24 h. At the end of the treatment period, apoptotic markers such as caspase 3 and 9, bcl-2, bax and cytochrome c were evaluated by semiquantitative reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction. SA-induced morphological changes were investigated by acridine orange/ethidium bromide dual staining.

Results:

SA inhibited the proliferation and induced cytotoxicity in SCC-25 cells in a concentration-dependent manner. SA treatment caused apoptosis-related morphological changes as evidenced by the dual staining and the modulation of apoptotic marker gene expressions. SA treatments modulated bcl-2/bax homeostasis and increased the expressions of cytochrome c and caspases 3 and 9.

Conclusion:

SA specifically induces cell death and inhibits the proliferation in OSCC cells through intrinsic/mitochondrial apoptosis pathway, suggesting that SA may be an effective agent for the treatment of human OSCC.

Keywords: Caspases, cytochrome c, cytotoxicity, polyphenol

INTRODUCTION

Oral squamous carcinoma cell (OSCC) is among the ten most frequent human malignancies[1] and is the most common malignancy of head-and-neck cancer.[2] Advanced oral cancers can cause significant morbidity and mortality. OSCC is highly invasive and destroys tissues, thus causing disfigurement, loss of function, pain, bleeding, and necrosis.[3] Tobacco chewing and smoking, alcohol consumption alone or with chewing tobacco and betel quid are potential carcinogens contributing to the high occurrence of OSCC.[4] High incidences of OSCC has been reported in developing countries due to different forms of smokeless tobacco exposure.[5] OSCC has a very poor prognosis, and it is often characterized by aggressive local invasion, early metastasis and poor response to chemotherapy.[2] Current treatment modalities for OSCC include chemo or radiotherapy, surgical removal of cancer, targeted therapy using epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors and cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors, and photodynamic therapy.[6] However, none of these therapies are curative but merely symptomatic, and these treatments produce only temporary clinical benefit and often led to the major problems related to nonspecific cell death and severe side effects.[2] Hence, there is a necessary to identify the key agents that control tumor proliferation and development of novel treatments that can block or inhibit invasion and/or metastasis is important for improving the prognosis of OSCC.

Several plants derived and synthetic compounds have been tested for their anticancer potential in experimental animals and in vitro OSCC cell lines.[7,8,9] Previous studies showed that plant-derived compounds could selectively target cancer cells and inhibit their proliferation and induce cytotoxicity via apoptosis and these effects are implicated as their beneficial effects against cancer.[8,9,10,11,12] Further, these plant-derived compounds have been reported to modify the redox status and interfere with basic cellular functions cell cycle, apoptosis, inflammation, angiogenesis, invasion and metastasis.[13] Several studies have shown that natural products have a wide spectrum of biological activities including anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, antimutagenic and anticancer properties.[14,15] Hence, in this study, we evaluated the cytotoxic effect of syringic acid (SA) in squamous carcinoma cell (SCC)-25 cell line.

SA, a known phenolic acid used in traditional Chinese herbal medicine, is an emerging nutraceutical for the treatment of cancer.[16] Studies were reported the hepatoprotective and anti-inflammatory, antimitogenic, antihyperglycemic, neuroprotective and memory-enhancing properties of SA in various animal models.[17,18,19,20] In the context of in vitro, the cytotoxic effect of SA has been explored in several cancer cell lines other than human OSCC.[16,19,21,22] Although SA has studied against various cancer types in vitro, its efficacy against human OSCC is not available. Hence, this study has been conducted to explore the anticancer efficacy of SA against OSCC SCC-25 cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals

S A (4-hydroxy-3,5-dimethoxybenzoic acid), 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium Bromide (MTT) and dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) was purchased from Sigma Chemical (Chennai, India). The other chemicals used in this study were purchased locally and were of analar grade.

Cell cultures and treatment

The SCC-25 human oral SCC line was procured from ATCC. Cells were maintained in Dulbecco's Minimum Essential Media and Ham's F-12 (1:1 ratio) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, with 100 units/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin. Cells were cultured in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2 at 37°C. Cells were grown in 75 cm2 culture flasks, and after a few passages, cells were seeded for experiments. The experiments were done at 70%–80% confluence. On reaching confluence, cells were detached using 0.05% Trypsin-ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid solution.

SA was dissolved in 0.1% DMSO (v/v). SCC-25 cells were plated at 10,000 cells/cm2. After 24 h, cells were fed with fresh expansion culture medium supplemented with different final concentrations of SA (25 and 50 μM) or the corresponding volumes of the vehicle. The concentrations (25 μM and 50 μM.) used in this study was based on previously published literature. In previous studies, 25 μM and 50 μM concentrations of SA was reported to inhibit cell proliferation and apoptosis of various cancer cells.[21,23] After 24 h of treatment, cells were collected by trypsin application. The total cell number was determined by counting each sample in triplicate under the inverted microscope.

3-(4,5-Dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide assay

Cytotoxic effect of SA in SCC-25 cells was assessed by MTT assay.[24] Cells were plated in 96-well plates at a concentration of 5 × 104 cells/well. After 24 h, cells were fed with fresh expansion culture medium supplemented with different final concentrations of SA (25 and 50 μM) and incubated for 24 h. Untreated cells served as control and received only 0.1% DMSO. At the end of the treatment period, media from control, SA-treated cells was discarded and 50 μl of MTT (0.5 mg/ml of phosphate-buffered saline [PBS]) was added to each well. Cells were then incubated for 4 h at 37°C in CO2 incubator. MTT was then discarded and the colored crystals of produced formazan were dissolved in 150 μl of DMSO and mixed effectively. The purple-blue formazan dye formed was measured using an ELISA reader (BIORAD) at 570 nm.

Acridine orange/ethidium bromide (dual staining)

Acridine orange/ethidium bromide (AO/EB) orange staining was carried out by the method of Gohel et al.[25] SCC-25 cells were plated at a density of 1 × 104 in 48-well plates. They were allowed to grow until they are 70%–80% confluent. After 24 h, the cells were treated with different concentrations of SA. The culture medium was aspirated from each well and cells were gently rinsed twice with PBS at room temperature. Then, equal volumes of cells from control and SA treated were mixed with 100 μl of dye mixture (1:1) of EB and AO and viewed immediately under Nikon inverted fluorescence microscope (Ti series) at ×10. A minimum of 300 cells was counted in each sample in two different fields. The percentage of apoptotic cells was determined by (% of apoptotic cells = [total number of apoptotic cells/total number of cells counted] ×100).

Gene expression analysis

Total RNA was extracted by trizol reagent according to the standard protocol. The concentration of the extracted RNA was determined, and the integrity of RNA was visualized on a 1% agarose gel using a gel documentation system (BioRad, Hercules, CA). The first strand of cDNA was synthesized from 1 μg of total RNA by reverse transcriptase using M-MLV (Promega, Madison, WI) and oligo (dT) primers (Promega) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Then, 2 μl of template cDNA was added to the final volume of 20 μl of the reaction mixture. Reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) cycle parameters included 10 min at 95°C followed by 40 cycles involving denaturation at 95°C for 15 s, annealing at 60°C for 20 s and elongation at 72°C for 20 s. The sequences of the specific sets of primer for bax, bcl-2, cytochrome c, caspase-3,-9 and GAPDH used in this study were taken from literature. Expressions of selected genes were normalized to the GAPDH gene, which was used as an internal housekeeping control. All the RT-PCR experiments were performed in triplicate.

Statistical analysis

Data were expressed as mean ± standard error of mean and analyzed by Tukey's test to determine the significance of differences between groups. P <0.05 0.01 or/and 0.001 was considered to be statistically significant.

RESULTS

Syringic acid treatments induced cytotoxicity in squamous carcinoma cell-25 cells

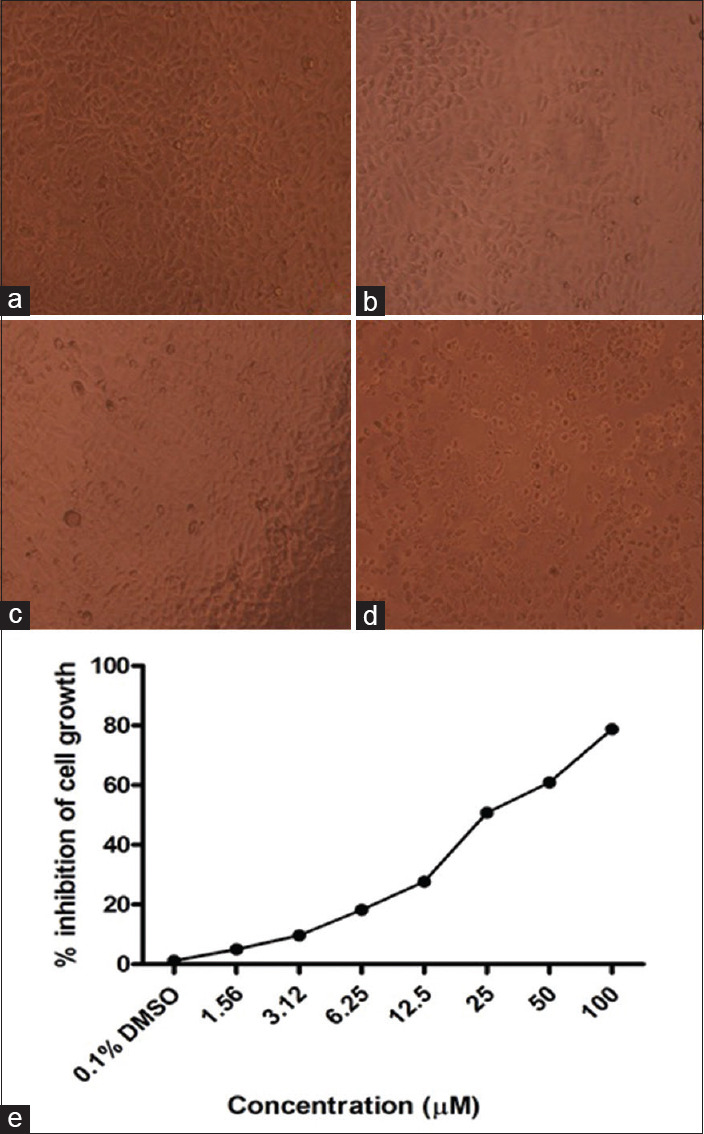

Initially, SCC-25 cells were treated with logarithmic concentrations (1.56, 3.12, 6.25, 12.5, 25, 50 and 100 μM) of SA and cell viability was determined by the MTT assay. The morphology of SA-treated cells is shown in Figure 1a-d. In this study, SA treatment for 24 h caused a marked increase in cell death in a concentration-dependent manner. At the end of 24 h, maximum inhibition (78%) of cell growth was found at a maximum concentration (100 μM) used in this study when compared to control. The control and DMSO-treated cells did not produce any significant change in the proliferation of SCC-25 cells [Figure 1e].

Figure 1.

Morphology of squamous carcinoma cell-25 cells after SA treatment (×10). (a) Control; (b) dimethyl sulfoxide (c and d) syringic acid treatments 25 and 50 μM treatments, respectively. (e) Cytotoxic effect of syringic acid was analyzed by 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide assay. Squamous carcinoma cell-25 cells were treated with different concentrations of syringic acid for 24 h. Values are expressed as mean ± standard error of mean (n = 3)

Syringic acid treatments induced apoptosis-related morphological changes in squamous carcinoma cell-25 cells

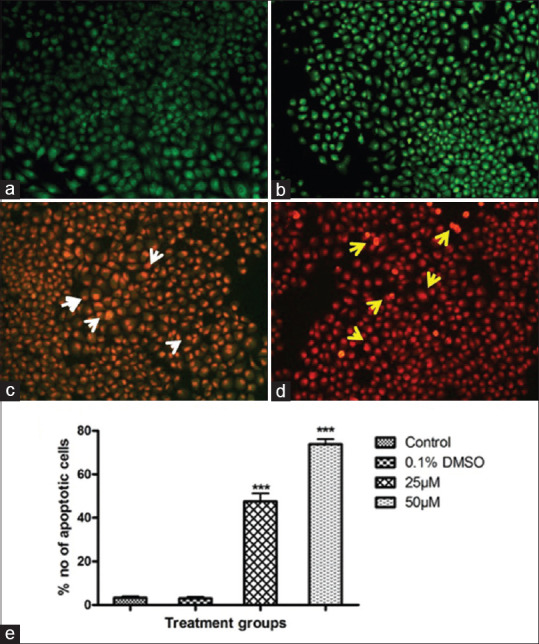

Dual AO/EB fluorescent staining can detect basic morphological changes in apoptotic cells of SA treated and control cells. Viable cell's DNA was stained by AO and their nuclei were bright green, while apoptotic cell's DNA were stained by EB and appears orange to red color. In this study, the negative control group (normal cells) and DMSO treated vehicle control group cells exhibit with the circular nucleus uniformly distributed in the center of the cell [Figure 2a and b]. In the experimental group, early apoptotic cells were visualized as yellow-green by AO nuclear staining after 25 μM of SA treatment in SCC-25 cells [Figure 2c]. While 50 μM-SA-treated cells show significant apoptosis as evidenced by orange or red color staining [Figure 2d]. The apoptotic nuclei counted were also showed a statistically significant (P< 0.001) increase in apoptotic cell number upon SA treatment in a concentration-dependent manner as compared to control [Figure 2e].

Figure 2.

Apoptosis analysis by acridine orange/ethidium bromide (×10). (a) Control; (b) dimethyl sulfoxide; (c and d) syringic acid treatments 25 and 50 μM treatments, respectively. White arrowheads show the early apoptotic cells; Yellow arrowheads show late apoptotic and DNA fragmented cells. (e) Quantification of apoptotic cells. Values are expressed as mean ± standard error of mean (n = 3). ***P < 0.001 compared to control

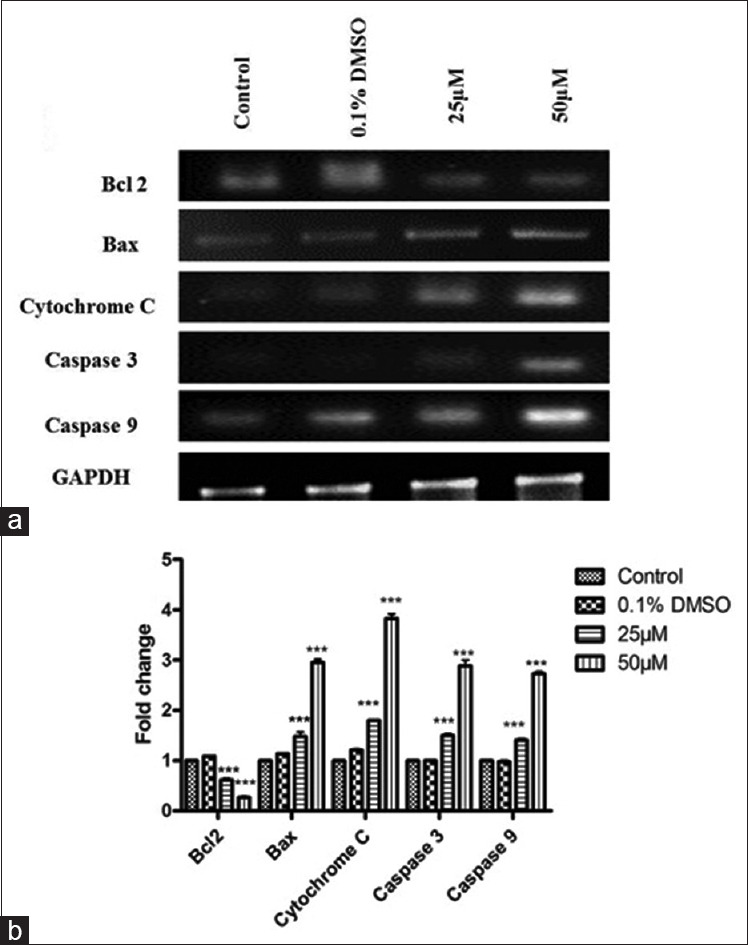

Syringic acid treatments modulated the apoptosis marker genes in squamous carcinoma cell-25 cells

To further substantiate our results at the molecular level, we evaluated the apoptosis marker gene expressions in control and SA-treated cells. SA treatments caused a significant up regulation of bax, cytochrome c and caspases (3 and 9) gene expressions in SCC-25 cells as compared to untreated control and DMSO-treated cells. Further, SA treatment downregulated the bcl-2 expression, an inhibitor of apoptosis in SCC-25 cells [Figure 3a and b]. In all cases, GAPDH used as an internal control for normalization.

Figure 3.

(a) Apoptotic marker gene expressions. GAPDH used as an internal control for optimization. (b) Quantification of gene expression values is expressed as mean ± standard error of mean (n = 3). P < 0.001 compared to control

DISCUSSION

Plants comprise an imperative source of active natural products and new drug entities, such as anticancer drugs.[26,27] SA has tested against a variety of cancer cells in vitro and was reported to produce cytotoxicity and growth inhibitory effects.[16,19,21,22] In the present study, SA treatments at 25 and 50 μM for 24 h and effectively induced cytotoxicity in OSCC. This is consistent with the previous reports, in which SA is suggested to target the basic mechanisms of proliferation in cancer cells.[16,19] To further delineate the mechanism of cytotoxicity induced by SA, we evaluated the proapoptotic potentials of this compound.

Apoptosis is a mechanism of programmed cell death and the induction of apoptosis is one of the underlying principles of most current cancer therapies.[28,29] Apoptotic changes are characterized by specific morphological and biochemical changes of dying cells, including cell shrinkage, nuclear condensation and fragmentation, dynamic membrane blebbing and loss of adhesion to neighbors or extracellular matrix.[30] Tumor cells undergo apoptosis in the presence of anticancer drugs, normal cells become necrotic if the drug is toxic and further, MTT assays cannot differentiate between these mechanisms of cell death.[31] The dual staining technique has been reported to effectively distinguish the normal and apoptotic cells.[25,31] Hence, we investigated the morphology of SA-treated cells by dual AO/EB fluorescent staining. In this study, SA treatment caused early and late apoptosis at 25 and 50 μM concentrations for 24 h, respectively. The fluorescent stain EB only entered cells with damaged membranes, such as late apoptotic and dead cells, emitting orange-red fluorescence when bound to concentrated DNA fragments or apoptotic bodies.[32] The presence of red fluorescent stained cells suggesting the fact that SA can induce the morphological changes related to apoptosis in SCC-25 cells.

To investigate the mechanism involved in apoptosis induction, we evaluated the molecular mechanism. During tumorigenesis, significant loss or inactivation of caspases leads to impairing apoptosis induction, causing a dramatic imbalance in the growth dynamics, ultimately resulting in the aberrant growth of human cancers.[33] In contrast, the induction of apoptosis is almost always associated with the activation of caspases; a conserved family of enzymes that irreversibly commit a cell to die. The release of cytochrome c from mitochondria to the cytosol after being induced by a variety of apoptosis-inducing agents leads to the formation of apoptosome which forms a platform for the efficient processing and activation of caspase-9. Activation of caspase-9, in turn, cleaves effectors caspases such as caspase-3 and 7 which eventually lead to apoptosis.[34,35] Therefore, in the next series of experiments, we investigated the proapoptotic effect of SA on the caspase cascade. Results from the present study demonstrated that mRNA expression levels of these caspases were significantly increased in SCC-25 cells upon SA treatment. Consistent with above reports, the activation of executioner caspases 3 and 9 could be the possible cause for the induction of apoptosis.

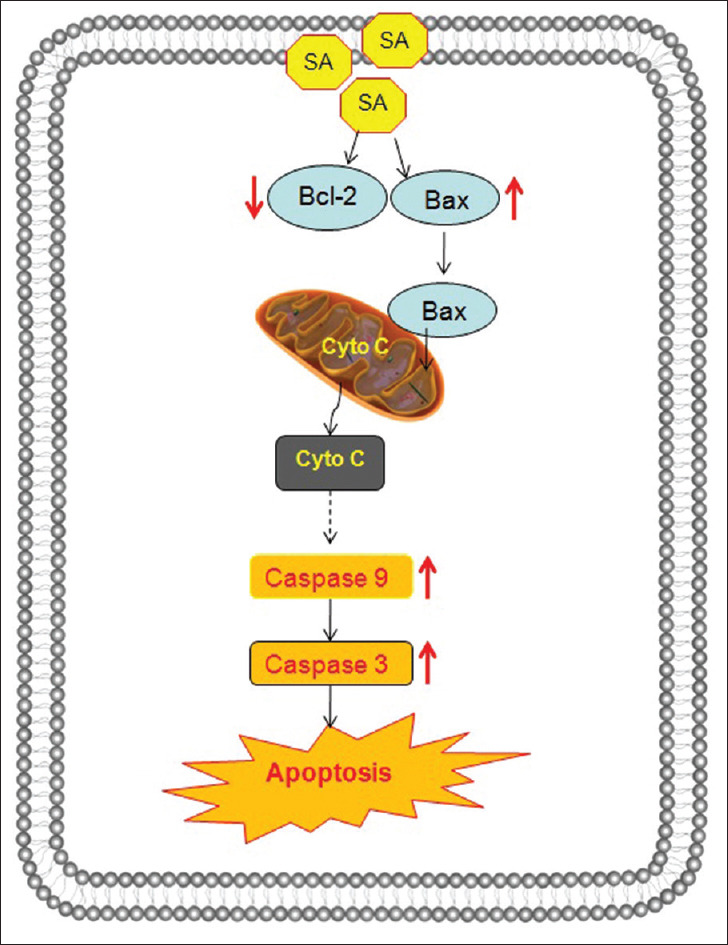

Bcl-2, anti-apoptotic gene, prevents apoptosis either by sequestering performs of caspases or by preventing the release of mitochondrial apoptogenic factors such as cytochrome c into the cytosol.[36] After entering into the cytosol, cytochrome c directly activates caspases that cleave a set of cellular proteins to cause apoptotic changes.[37,38] Mitochondria induce apoptosis by releasing cytochrome c that participates in caspase activation. In contrast, a pro-apoptotic member such as bax trigger the release of caspases from death antagonists via heterodimerization and also by inducing the release of mitochondrial cytochrome c into the cytoplasm via acting on mitochondrial permeability transition pore, thereby leading to caspase activation.[38] In this study, SA treatment caused a significant upregulation of bax (a proapoptotic signal to mitochondria) expression, and it was well correlated with the significant downregulation of an anti-apoptotic gene, i.e., bcl-2 expression. Results from the current study suggest that the strong proapoptotic bax signal could have act on mitochondria and inhibited the antiapoptoic signal (bcl-2 expression), and this in turn induced the cytochrome c release into the cytosol for the caspase activation and induction of apoptosis [Figure 4]. These findings suggest that SA induce the cytotoxicity through induction of apoptosis via intrinsic or mitochondrial pathway in SCC-25 cell lines.

Figure 4.

Probable mechanism of apoptosis induction by syringic acid treatment in squamous carcinoma cell-25 cells

CONCLUSION

SA has a potent cytotoxic effect on human oral SCCs. SA induced mitochondria-meadiated apoptosis via cytochrome c release and caspases 9 and 3 activation. SA treatment also increases the bax expression, and it was well correlated with concomitant downregulation of bcl-2 gene expression. Our molecular findings are well corroborated with dual staining assay. SA may be an effective therapeutic strategy for human oral squamous carcinoma.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Eckert AW, Wickenhauser C, Salins PC, Kappler M, Bukur J, Seliger B, et al. Clinical relevance of the tumor microenvironment and immune escape of oral squamous cell carcinoma. J Transl Med. 2016;14:85. doi: 10.1186/s12967-016-0828-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li P, Xiao LY, Tan H. Muc-1 promotes migration and invasion of oral squamous cell carcinoma cells via PI3K-Akt signaling. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2015;8:10365–74. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ezhilarasan D, Apoorva VS, Ashok Vardhan N. Syzygium cumini extract induced reactive oxygen species-mediated apoptosis in human oral squamous carcinoma cells. J Oral Pathol Med. 2019;48:115–21. doi: 10.1111/jop.12806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alaeddini M, Etemad-Moghadam S. Lymphangiogenesis and angiogenesis in oral cavity and lower lip squamous cell carcinoma. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2016;82:385–90. doi: 10.1016/j.bjorl.2015.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Malik UU, Zarina S, Pennington SR. Oral squamous cell carcinoma: Key clinical questions, biomarker discovery, and the role of proteomics. Arch Oral Biol. 2016;63:53–65. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2015.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gharat SA, Momin M, Bhavsar C. Oral squamous cell carcinoma: Current treatment strategies and nanotechnology-based approaches for prevention and therapy. Crit Rev Ther Drug Carrier Syst. 2016;33:363–400. doi: 10.1615/CritRevTherDrugCarrierSyst.2016016272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Han Y, Cui Z, Li YH, Hsu WH, Lee BH. In vitro and in vivo anticancer activity of pardaxin against proliferation and growth of oral squamous cell carcinoma. Mar Drugs. 2015;14:2. doi: 10.3390/md14010002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mohan S, Thiagarajan K, Chandrasekaran R. In vitro evaluation of antiproliferative effect of ethyl gallate against human oral squamous carcinoma cell line KB. Nat Prod Res. 2015;29:366–9. doi: 10.1080/14786419.2014.942303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kwak HH, Kim IR, Kim HJ, Park BS, Yu SB. A-mangostin induces apoptosis and cell cycle arrest in oral squamous cell carcinoma cell. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2016;2016:5352412. doi: 10.1155/2016/5352412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cha JD, Jeong MR, Kim HY, Lee JC, Lee KY. MAPK activation is necessary to the apoptotic death of KB cells induced by the essential oil isolated from Artemisia iwayomogi. J Ethnopharmacol. 2009;123:308–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2009.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liang CH, Wang GH, Liaw CC, Lee MF, Wang SH, Cheng DL, et al. Extracts from Cladiella australis, Clavularia viridis and Klyxum simplex (soft corals) are capable of inhibiting the growth of human oral squamous cell carcinoma cells. Mar Drugs. 2008;6:595–606. doi: 10.3390/md6040595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rauth S, Ray S, Bhattacharyya S, Mehrotra DG, Alam N, Mondal G, et al. Lupeol evokes anticancer effects in oral squamous cell carcinoma by inhibiting oncogenic EGFR pathway. Mol Cell Biochem. 2016;417:97–110. doi: 10.1007/s11010-016-2717-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kampa M, Nifli AP, Notas G, Castanas E. Polyphenols and cancer cell growth. Rev Physiol Biochem Pharmacol. 2007;159:79–113. doi: 10.1007/112_2006_0702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Espín JC, García-Conesa MT, Tomás-Barberán FA. Nutraceuticals: Facts and fiction. Phytochemistry. 2007;68:2986–3008. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2007.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miyata T. Pharmacological basis of traditional medicines and health supplements as curatives. J Pharmacol Sci. 2007;103:127–31. doi: 10.1254/jphs.cpj06016x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gheena S, Ezhilarasan D. Syringic acid triggers reactive oxygen species-mediated cytotoxicity in HepG2 cells. Hum Exp Toxicol. 2019;38:694–702. doi: 10.1177/0960327119839173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Güven M, Aras AB, Topaloǧlu N, Özkan A, Şen HM, Kalkan Y, et al. The protective effect of syringic acid on ischemia injury in rat brain. Turk J Med Sci. 2015;45:233–40. doi: 10.3906/sag-1402-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ham JR, Lee HI, Choi RY, Sim MO, Seo KI, Lee MK. Anti-steatotic and anti-inflammatory roles of syringic acid in high-fat diet-induced obese mice. Food Funct. 2016;7:689–97. doi: 10.1039/c5fo01329a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abaza MS, Al-Attiyah R, Bhardwaj R, Abbadi G, Koyippally M, Afzal M. Syringic acid from Tamarix aucheriana possesses antimitogenic and chemo-sensitizing activities in human colorectal cancer cells. Pharm Biol. 2013;51:1110–24. doi: 10.3109/13880209.2013.781194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Srinivasan S, Muthukumaran J, Muruganathan U, Venkatesan RS, Jalaludeen AM. Antihyperglycemic effect of syringic acid on attenuating the key enzymes of carbohydrate metabolism in experimental diabetic rats. Biomed Prev Nutr. 2014;4:595–602. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Karthik G, Vijayakumar A, Natarajapillai S. Preliminary study on salubrious effect of syringic acid on apoptosis in human Lung carcinoma a549 cells and in silico analysis through docking studies. Asian J Pharm Clin Res. 2014;7:46–9. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Orabi KY, Abaza MS, El Sayed KA, Elnagar AY, Al-Attiyah R, Guleri RP. Selective growth inhibition of human malignant melanoma cells by syringic acid-derived proteasome inhibitors. Cancer Cell Int. 2013;13:82. doi: 10.1186/1475-2867-13-82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huang SM, Chuang HC, Wu CH, Yen GC. Cytoprotective effects of phenolic acids on methylglyoxal-induced apoptosis in neuro-2A cells. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2008;52:940–9. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.200700360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Safadi FF, Xu J, Smock SL, Kanaan RA, Selim AH, Odgren PR, et al. Expression of connective tissue growth factor in bone: Its role in osteoblast proliferation and differentiation in vitro and bone formation in vivo. J Cell Physiol. 2003;196:51–62. doi: 10.1002/jcp.10319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gohel A, McCarthy MB, Gronowicz G. Estrogen prevents glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis in osteoblasts in vivo and in vitro. Endocrinology. 1999;140:5339–47. doi: 10.1210/endo.140.11.7135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ezhilarasan D. Herbal therapy for cancer: Clinical and experimental perspectives. In: Timiri Shanmugam P, editor. Understanding Cancer Therapies. 1st ed. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 2018. pp. 129–66. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ezhilarasan D, Sokal E, Karthikeyan S, Najimi M. plant derived antioxidants and antifibrotic drugs: Past, present and future. J Coast Life Med. 2014;2:738–45. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ouyang L, Shi Z, Zhao S, Wang FT, Zhou TT, Liu B, et al. Programmed cell death pathways in cancer: A review of apoptosis, autophagy and programmed necrosis. Cell Prolif. 2012;45:487–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2184.2012.00845.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Westhoff MA, Marschall N, Debatin KM. Novel approaches to apoptosis-inducing therapies. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2016;930:173–204. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-39406-0_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nishida K, Yamaguchi O, Otsu K. Crosstalk between autophagy and apoptosis in heart disease. Circ Res. 2008;103:343–51. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.175448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu K, Liu PC, Liu R, Wu X. Dual AO/EB staining to detect apoptosis in osteosarcoma cells compared with flow cytometry. Med Sci Monit Basic Res. 2015;21:15–20. doi: 10.12659/MSMBR.893327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ribble D, Goldstein NB, Norris DA, Shellman YG. A simple technique for quantifying apoptosis in 96-well plates. BMC Biotechnol. 2005;5:12. doi: 10.1186/1472-6750-5-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fiandalo MV, Kyprianou N. Caspase control: Protagonists of cancer cell apoptosis. Exp Oncol. 2012;34:165–75. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McIlwain DR, Berger T, Mak TW. Caspase functions in cell death and disease. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2013;5:a008656. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a008656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cai J, Yang J, Jones DP. Mitochondrial control of apoptosis: The role of cytochrome c. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998;1366:139–49. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(98)00109-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yip KW, Reed JC. Bcl-2 family proteins and cancer. Oncogene. 2008;27:6398–406. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Portt L, Norman G, Clapp C, Greenwood M, Greenwood MT. Anti-apoptosis and cell survival: A review. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1813:238–59. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2010.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tsujimoto Y. Role of Bcl-2 family proteins in apoptosis: Apoptosomes or mitochondria? Genes Cells. 1998;3:697–707. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2443.1998.00223.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]