Significance Statement

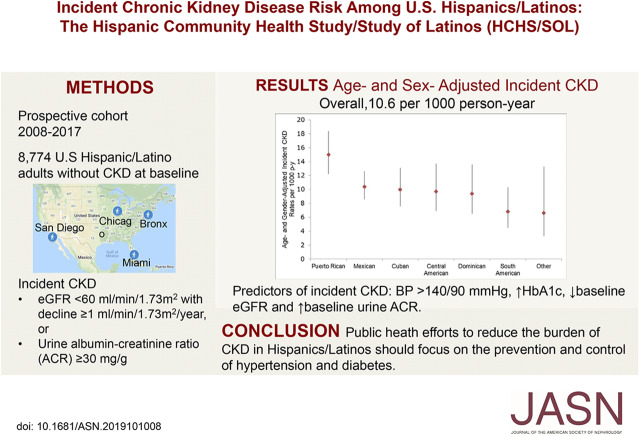

Although the incident rate of ESKD is higher among Hispanics/Latinos living in the United States compared with non-Hispanics, less is known about incident rates of CKD. The authors report that this community-based prospective cohort study of more than 8000 Hispanics/Latinos in the United States found the overall rate of incident CKD to be 10.6 per 1000 person-years, with the highest rate observed among Puerto Ricans (15.0 per 1000 person-years). Important risk factors for new-onset CKD included elevated BP and glycated hemoglobin, as well as lower baseline eGFR and higher baseline albumin-to-creatinine ratio. Culturally tailored public heath interventions among Hispanics/Latinos focusing on prevention and control of risk factors, including diabetes and hypertension, might help decrease their burden of CKD and ESKD.

Keywords: CKD, clinical epidemiology, risk factors

Visual Abstract

Abstract

Background

Although Hispanics/Latinos in the United States are often considered a single ethnic group, they represent a heterogenous mixture of ancestries who can self-identify as any race defined by the U.S. Census. They have higher ESKD incidence compared with non-Hispanics, but little is known about the CKD incidence in this population.

Methods

We examined rates and risk factors of new-onset CKD using data from 8774 adults in the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos. Incident CKD was defined as eGFR <60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 with eGFR decline ≥1 ml/min per 1.73 m2 per year, or urine albumin/creatinine ratio ≥30 mg/g. Rates and incidence rate ratios were estimated using Poisson regression with robust variance while accounting for the study’s complex design.

Results

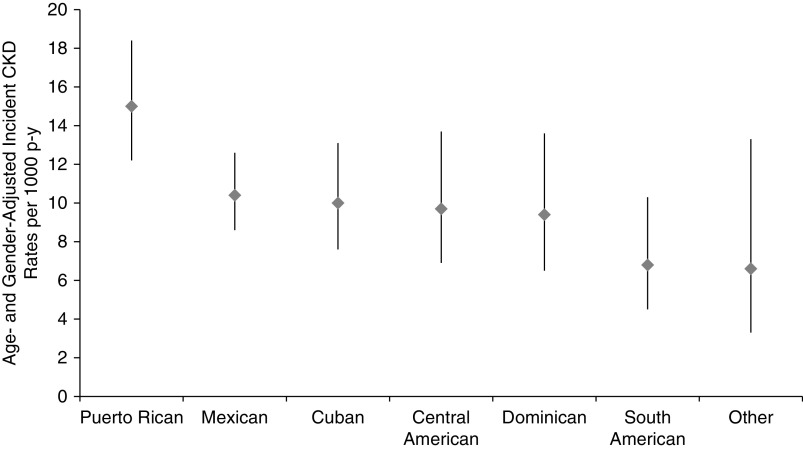

Mean age was 40.3 years at baseline and 51.6% were women. In 5.9 years of follow-up, 648 participants developed CKD (10.6 per 1000 person-years). The age- and sex-adjusted incidence rates ranged from 6.6 (other Hispanic/mixed background) to 15.0 (Puerto Ricans) per 1000 person-years. Compared with Mexican background, Puerto Rican background was associated with 79% increased risk for incident CKD (incidence rate ratios, 1.79; 95% confidence interval, 1.33 to 2.40), which was accounted for by differences in sociodemographics, acculturation, and clinical characteristics. In multivariable regression analysis, predictors of incident CKD included BP >140/90 mm Hg, higher glycated hemoglobin, lower baseline eGFR, and higher baseline urine albumin/creatinine ratio.

Conclusions

CKD incidence varies by Hispanic/Latino heritage and this disparity may be in part attributed to differences in sociodemographic characteristics. Culturally tailored public heath interventions focusing on the prevention and control of risk factors might ameliorate the CKD burden in this population.

CKD is a global public health problem that affects over 30 million people living in the U.S.,1 including one in seven Hispanics/Latinos.2 Hispanics/Latinos are the largest minority group in the U.S.,3 and although they are often considered a single ethnic group, U.S. Hispanics/Latinos represent a heterogeneous mixture of Native American, European, and African ancestries who can self-identify as any race as defined by the U.S. Census.4 This heterogeneity is evident in the range of prevalence of risk factors across Hispanic/Latino background groups, with Puerto Ricans having the highest prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors5 and CKD,2 and Mexicans having the highest prevalence of diabetes.6 Furthermore, compared with non-Hispanic whites, individuals of Hispanic/Latino origin suffer from a higher burden of kidney disease and cardiovascular risk factors, including higher prevalence of diabetes,6,7 uncontrolled hypertension,8 and obesity.9 However, only limited data are available regarding the rates and risk factors for incident CKD among Hispanics/Latinos. We evaluated the rates and risk factors for incident CKD in the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos (HCHS/SOL).

Methods

Study Participants

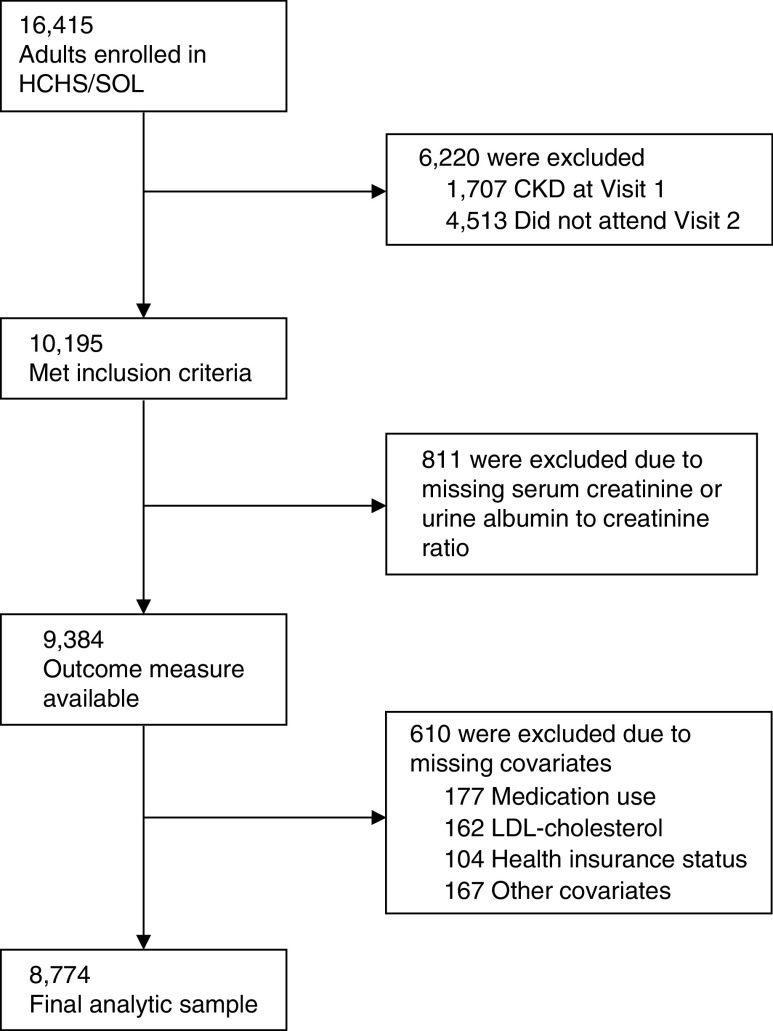

HCHS/SOL is a population-based cohort of 16,415 Hispanics/Latinos aged 18–74 years from randomly selected households in four U.S. field centers (Chicago, IL; Miami, FL; Bronx, NY; and San Diego, CA) with baseline examination (2008–2011), yearly telephone follow-up assessment, and a follow-up clinic visit (2014–2017). Participants self-reported their background as Cuban, Dominican, Mexican, Puerto Rican, Central American, or South American. The category “other” was used for participants belonging to a group not listed or to more than one group. The sample design and cohort selection have been previously described.10,11 Briefly, a stratified two-stage area probability sample of household addresses was selected in each field center. The first sampling stage randomly selected census block groups with stratification on the basis of Hispanic/Latino concentration and proportion of high/low socioeconomic status. The second sampling stage randomly selected households, with stratification, from U.S. Postal Service registries that covered the randomly selected census block groups. Lastly, the study oversampled the 45–74 age group (n=9714, 59.2%) to facilitate examination of target outcomes. Sampling weights were generated to reflect the probabilities of selection at each stage. Of 39,384 individuals who were screened and selected, and who met eligibility criteria, 41.7% were enrolled, representing 16,415 persons from 9872 households. For this study, of the 16,415 individuals enrolled in HCHS/SOL, 1707 were excluded due to prevalent CKD at baseline [defined as eGFR <60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 or urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio (ACR) ≥30 mg/g], and 4513 due to lack of participation in the follow-up visit, leaving a sample of 10,195 eligible participants. Of those, 811 had missing data on CKD markers (serum creatinine or urine ACR) at the follow-up visit, and 610 had missing baseline covariate data [medication use (177), LDL-cholesterol (162), health insurance status (104), or other covariates (167)] (Figure 1). After examining the missing data pattern for covariates included in our analysis, we decided to use complete case analysis of the 8774 adults who had no missing data for any variable. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards for reading centers, the coordinating center, and at each field center where all participants gave written consent, and is in adherence to the Declaration of Helsinki.

Figure 1.

Enrollment, eligibility, and analysis populations.

Baseline Measurements and Definitions

The baseline study examination included clinical measurements, questionnaires, and fasting venous blood and urine specimens. Demographic factors, socioeconomic status, cigarette smoking, physical activity, and medical history were obtained using standard questionnaires. Acculturation was evaluated using a modified version of the Short Acculturation Scale for Hispanics,12 place of birth, and language of interview. Medication use was ascertained by conducting a scanned inventory of all currently used medications. BP was defined as the average of three repeat seated measurements obtained after a 5-minute rest. Hypertension was defined as systolic BP ≥140 mm Hg, or diastolic BP ≥90 mm Hg, or use of antihypertensive medication. Diabetes mellitus was defined as fasting plasma glucose of ≥126 mg/dl, 2-hour postload glucose levels of ≥200 mg/dl, glycated hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) level of ≥6.5%, or use of antidiabetic medication.

Measurements of Kidney Function and Damage

Measures of kidney function and damage were obtained at the baseline visit and at the follow-up visit. GFR was estimated using the CKD Epidemiology Collaboration creatinine-cystatin C equation.13 The outcome of interest was the development of CKD defined as eGFR <60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 and eGFR decline ≥1 ml/min per year,14 or ACR ≥30 mg/g at the follow-up examination.15 Creatinine was measured in serum and urine on a Roche Modular P Chemistry Analyzer (Gentian AS, Moss, Norway) using a creatinase enzymatic method (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN), with a within-individual coefficient of variation (CVI) of 7.3, and a between-individual coefficient of variation (CVG) of 39.2.16 Serum creatinine measurements were isotope dilution mass spectrometry traceable. Urine albumin was measured using an immunoturbidometric method on a ProSpec nephelometric analyzer (Dade Behring GMBH, Marburg, Germany). Serum cystatin C was measured using a turbidimetric method on a Roche Modular P Chemistry Analyzer, with CVI of 5.2 and CVG of 25.6.16

Statistical Analyses

Summary statistics, incidence rates, and incidence rate ratios (IRR) were weighted to adjust for sampling probability and nonresponse, as previously described.16,17 All analyses accounted for cluster sampling and the use of stratification in sample selection. We first calculated summary statistics for continuous [mean and 95% confidence interval (CI)] and categorical variables (percentage and SEM) for the overall study sample, as well as by Hispanic/Latino background. We then estimated the incidence rate for CKD per 1000 person-years for the overall sample, as well as by Hispanic/Latino background, age group, gender, diabetes status, hypertension status, and prevalent cardiovascular disease status. Poisson regression was used to estimate the incidence rates in these groups. We then performed a sequential modeling procedure to assess the IRR for individuals of given Hispanic/Latino backgrounds compared with individuals of Mexican background using Poisson regression, a log link function, and an offset for time between visit 1 and visit 2. The base model contained only individuals of Hispanic/Latino background (model 1). Model 2 additionally adjusted for age, sex, education, income, health insurance status, whether the individual was U.S. born, and primary language (model 2). Model 3 additionally adjusted for smoking, hypertension, diabetes, prevalent cardiovascular disease, systolic BP, HbA1c, C-reactive protein, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor/angiotensin receptor blocker (ACEi/ARB) use, statin use, calcium channel blocker use, antiplatelet use, baseline eGFR, and ACR.

All statistical tests were two-sided at a significance level of 0.05. No adjustments were made for multiple comparisons. All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute) and SUDAAN 11.0.1.

Results

Of the 16,415 HCHS/SOL participants, 8774 were included in this study (Figure 1). The mean (95% CI) age at baseline was 40.3 (39.7 to 40.8) years, and participants of Cuban background had higher mean age (45.2 years) compared with the other background groups (Table 1). Overall, 51.6% of participants were women, and the highest proportion of women was observed among Dominicans (60.1%). The prevalence of educational attainment lower than high school ranged from 18.3% among other/mixed Hispanic/Latino background to 40.4% among Dominicans. Low income (annual family income <$20,000) was reported by 46.6% of participants, and ranged from 39.6% among Mexicans to 54.0% in Cubans. Overall, 12.7% of participants had diabetes; prevalence ranged from 7.0% among other/mixed Hispanic/Latino background to 16.6% in Puerto Ricans. The overall prevalence of hypertension was 21.2%, and ranged between 13.4% in Mexicans and 31.2% in Cubans. Mean baseline eGFR and urine ACR were 108.7 ml/min per 1.73 m2 and 5.7 mg/g, respectively. Baseline characteristics of the entire HCHS/SOL cohort, eligible participants, and current study sample are presented in Supplemental Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of HCHS/SOL participants without CKD at baseline by Hispanic/Latino Background

| Variable | Overall (n=8774)a | Dominican (n=750) | Central American (n=890) | Cuban (n=1262) | Mexican (n=3681) | Puerto Rican (n=1321) | South American (n=627) | Other (n=243) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, yr | 40.3 (39.7 to 40.8) | 40.2 (38.5 to 41.8) | 38.7 (37.4 to 39.9) | 45.2 (43.9 to 46.5) | 37.8 (37.0 to 38.7) | 42.4 (41.1 to 43.6) | 41.9 (40.0 to 43.7) | 32.9 (30.8 to 34.9) |

| Female sex | 51.6 (0.7) | 60.1 (2.6) | 52.9 (2.5) | 47.0 (1.7) | 53.2 (1.3) | 50.0 (2.0) | 52.4 (2.6) | 44.2 (4.5) |

| Less than high school education | 31.2 (0.9) | 40.4 (2.6) | 38.2 (2.5) | 20.2 (1.6) | 34.6 (1.5) | 35.6 (2.1) | 21.0 (2.3) | 18.3 (3.7) |

| Annual income <$20,000 | 46.6 (1.1) | 52.9 (2.6) | 51.2 (3.0) | 54.0 (2.4) | 39.6 (1.7) | 51.9 (2.1) | 45.2 (3.0) | 40.0 (4.9) |

| Health insurance | 50.0 (1.1) | 72.0 (2.5) | 33.6 (2.9) | 40.9 (2.3) | 41.3 (1.6) | 80.2 (1.7) | 40.0 (2.8) | 55.8 (4.8) |

| Spanish language | 75.3 (1.0) | 80.5 (2.4) | 87.0 (2.1) | 90.7 (1.5) | 78.9 (1.2) | 42.5 (2.3) | 88.7 (2.0) | 41.8 (4.7) |

| Acculturation: language subscale | 2.1 (0.03) | 1.9 (0.06) | 1.8 (0.06) | 1.6 (0.05) | 2.0 (0.03) | 3.1 (0.05) | 1.9 (0.05) | 3.1 (0.11) |

| U.S. born | 23.2 (0.9) | 11.6 (2.0) | 7.8 (1.4) | 9.3 (1.7) | 23.7 (1.3) | 49.2 (2.1) | 5.3 (1.5) | 62.2 (4.4) |

| ≥10 yr in the U.S. | 71.3 (1.1) | 69.4 (2.6) | 63.4 (2.9) | 49.0 (2.5) | 76.3 (1.4) | 92.5 (1.5) | 60.8 (3.5) | 86.1 (3.5) |

| Diabetes | 12.7 (0.5) | 13.5 (1.4) | 11.5 (1.3) | 12.7 (1.2) | 12.1 (0.7) | 16.6 (1.3) | 9.6 (1.5) | 7.0 (1.7) |

| Hypertension | 21.2 (0.7) | 26.3 (1.8) | 18.3 (1.7) | 31.2 (1.8) | 13.4 (0.9) | 28.7 (1.6) | 16.2 (1.9) | 16.8 (3.2) |

| Cardiovascular disease | 4.6 (0.3) | 4.5 (0.9) | 3.4 (0.7) | 5.1 (0.7) | 3.7 (0.5) | 7.0 (0.8) | 3.5 (1.0) | 4.8 (2.2) |

| Current smoker | 19.8 (0.7) | 11.2 (1.9) | 13.3 (1.7) | 25.6 (1.9) | 16.1 (1.1) | 32.1 (2.0) | 11.7 (1.7) | 21.6 (3.7) |

| Physically inactive | 20.2 (0.7) | 17.8 (1.8) | 16.9 (1.6) | 31.2 (1.9) | 16.6 (0.9) | 19.1 (1.5) | 20.7 (2.0) | 13.6 (3.0) |

| SBP, mm Hg | 119 (118 to 119) | 121 (119 to 123) | 119 (118 to 121) | 122 (121 to 124) | 115 (115 to 116) | 121 (120 to 122) | 117 (116 to 119) | 117 (114 to 120) |

| DBP, mm Hg | 72 (71 to 72) | 74 (73 to 75) | 72 (71 to 73) | 74 (74 to 75) | 69 (68 to 70) | 73 (73 to 74) | 70 (69 to 71) | 72 (69 to 74) |

| SBP >140 or DBP >90 mm Hg | 10.7 (0.5) | 13.3 (1.3) | 12.2 (1.5) | 16.6 (1.4) | 6.0 (0.7) | 13.2 (1.2) | 8.0 (1.4) | 10.6 (2.7) |

| Waist circumference, cm | 97.0 (96.5 to 97.5) | 95.6 (94.1 to 97.0) | 93.6 (92.6 to 94.7) | 96.8 (95.7 to 97.9) | 97.6 (96.8 to 98.3) | 99.2 (97.9 to 100.6) | 93.2 (92.0 to 94.5) | 98.1 (95.4 to 100.9) |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 29.3 (29.0 to 29.5) | 29.3 (28.6 to 29.9) | 28.5 (28.1 to 29.0) | 28.8 (28.3 to 29.3) | 29.2 (28.9 to 29.5) | 30.6 (30.0 to 31.1) | 28.0 (27.4 to 28.5) | 29.7 (28.6 to 30.8) |

| Obesity (BMI ≥30 kg/m2) | 39.2 (0.8) | 41.2 (2.5) | 34.6 (1.8) | 37.0 (2.1) | 40.0 (1.5) | 44.1 (2.1) | 28.3 (2.3) | 42.2 (4.2) |

| ACEi/ARB use | 9.8 (0.4) | 13.0 (1.5) | 6.8 (0.9) | 14.3 (1.3) | 6.2 (0.5) | 13.9 (1.1) | 7.9 (1.4) | 6.3 (1.5) |

| Statin use | 7.1 (0.4) | 9.2 (1.1) | 4.9 (0.8) | 7.0 (1.0) | 5.0 (0.5) | 13.4 (1.1) | 6.5 (1.2) | 3.7 (1.1) |

| Calcium channel blocker use | 3.4 (0.3) | 6.7 (1.1) | 1.7 (0.4) | 4.9 (0.7) | 1.4 (0.3) | 5.7 (0.8) | 2.6 (0.7) | 2.1 (1.0) |

| Antiplatelet use | 0.9 (0.1) | 0.5 (0.2) | 0.4 (0.2) | 2.3 (0.6) | 0.2 (0.0) | 1.5 (0.4) | 1.5 (0.9) | 0.0 (0.0) |

| LDL-cholesterol, mg/dl | 120.2 (119.0 to 121.4) | 117.5 (113.5 to 121.6) | 122.6 (118.2 to 127.1) | 127.0 (123.8 to 130.2) | 119.7 (117.8 to 121.6) | 114.1 (111.0 to 117.2) | 123.1 (119.4 to 126.7) | 113.1 (106.3 to 119.9) |

| HDL-cholesterol, mg/dl | 48.8 (48.3 to 49.2) | 50.8 (49.5 to 52.1) | 48.3 (47.2 to 49.3) | 48.1 (47.2 to 49.1) | 48.6 (47.9 to 49.3) | 48.2 (47.2 to 49.2) | 50.0 (48.9 to 51.2) | 49.9 (47.3 to 52.5) |

| HbA1c, % | 5.6 (5.6 to 5.7) | 5.6 (5.5 to 5.8) | 5.6 (5.5 to 5.7) | 5.6 (5.5 to 5.7) | 5.6 (5.6 to 5.7) | 5.7 (5.7 to 5.8) | 5.5 (5.5 to 5.6) | 5.4 (5.3 to 5.5) |

| eGFR, ml/min per 1.73 m2 | 108.7 (0.35) | 108.9 (0.99) | 111.0 (0.72) | 102.8 (0.65) | 113.5 (0.53) | 101.9 (0.82) | 111.1 (1.11) | 111.6 (1.29) |

| Urine ACR, mg/g, median (IQR) | 5.7 (4.1 to 8.7) | 5.5 (4.1 to 8.6) | 5.4 (3.9 to 8.6) | 5.7 (4.1 to 8.7) | 5.9 (4.2 to 8.8) | 5.5 (4.1 to 8.9) | 5.5 (4.1 to 7.9) | 5.6 (3.9 to 8.1) |

| CRP, mg/L | 3.6 (3.4 to 3.8) | 4.0 (3.3 to 4.7) | 3.3 (2.9 to 3.8) | 3.7 (3.3 to 4.1) | 3.3 (3.0 to 3.6) | 4.4 (3.9 to 4.9) | 2.9 (2.5 to 3.4) | 3.5 (2.7 to 4.3) |

SBP, systolic BP; DBP, diastolic BP; BMI, body mass index; IQR, interquartile range; CRP, C-reactive protein.

Values are presented as mean (95% CI) or % (SEM), unless otherwise specified.

During median 5.9 (interquartile range 5.5–6.4) years of follow-up, there were 648 incident CKD events (166 participants developed isolated eGFR <60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 with a decline in eGFR ≥1 ml/min per 1.73 m2 per year, 265 participants developed isolated urine ACR ≥30 mg/g, and the remaining 217 developed a combination of both). The overall age- and sex-adjusted rate of incident CKD was 10.6 (95% CI, 9.5 to 11.9) per 1000 person-years, and ranged from 6.6 (95% CI, 3.3 to 13.3) in other/mixed background to 15.0 (95% CI, 12.2 to 18.4) per 1000 person-years among Puerto Ricans (Figure 2, Table 2). Sex-adjusted incident CKD rates were highest among participants 18–44 years of age [10.6 (95% CI, 9.5 to 11.9) per 1000 person-years] compared with other age groups (Table 2). Age-adjusted rates were higher among men [10.6 (95% CI, 9.5 to 11.9) per 1000 person-years] compared with women [9.5 (7.9 to 11.5) per 1000 person-years] (Table 2). Kidney function and other clinical characteristic of individuals who developed CKD, as well as their eGFR and albuminuria categories, are presented in Supplemental Tables 2 and 3.

Figure 2.

Age- and sex-adjusted rates of incident CKD per 1000 person-years by Hispanic/Latino background group. p-y, patient-year.

Table 2.

Rates of incident CKD overall, and stratified by selected variables

| Variable | n | Events, n | Weighted Rate (per 1000 person-yr) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted | Age- and Sex-Adjusted | |||

| Overall | 8774 | 648 | 10.5 (9.3 to 11.8) | 10.6 (9.5 to 11.9) |

| Hispanic/Latino background | ||||

| Cuban | 1262 | 90 | 12.0 (9.1 to 15.7) | 10.0 (7.6 to 13.1) |

| Dominican | 750 | 48 | 9.4 (6.5 to 13.6) | 9.4 (6.5 to 13.6) |

| Mexican | 3681 | 249 | 9.1 (7.4 to 11.1) | 10.4 (8.6 to 12.6) |

| Puerto Rican | 1321 | 148 | 16.2 (13.0 to 20.1) | 15.0 (12.2 to 18.4) |

| Central American | 890 | 65 | 8.8 (6.3 to 12.4) | 9.7 (6.9 to 13.7) |

| South American | 627 | 36 | 7.2 (4.6 to 11.0) | 6.8 (4.5 to 10.3) |

| Other | 243 | 12 | 4.7 (2.3 to 9.5) | 6.6 (3.3 to 13.3) |

| Age, yr | ||||

| 18–44 | 3290 | 152 | 6.4 (5.2 to 7.8) | 10.6 (9.5 to 11.9) |

| 45–54 | 2844 | 145 | 9.0 (7.2 to 11.3) | 6.4 (5.2 to 7.9) |

| 55–74 | 2640 | 351 | 25.5 (22.1 to 29.4) | 9.0 (7.2 to 11.3) |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 3252 | 225 | 9.0 (7.4 to 10.9) | 10.6 (9.5 to 11.9) |

| Female | 5522 | 423 | 11.9 (10.3 to 13.7) | 9.5 (7.9 to 11.5) |

| Diabetes | ||||

| Yes | 3552 | 232 | 9.7 (8.1 to 11.6) | 8.8 (7.1 to 10.9) |

| No | 3626 | 153 | 6.7 (5.3 to 8.4) | 10.6 (9.5 to 11.9) |

| Hypertension | ||||

| Yes | 2499 | 343 | 24.8 (21.5 to 28.5) | 7.8 (6.6 to 9.2) |

| No | 6275 | 305 | 6.8 (5.7 to 8.0) | 10.6 (9.5 to 11.9) |

| Cardiovascular disease | ||||

| Yes | 486 | 75 | 27.8 (21.0 to 36.9) | 10.0 (8.9 to 11.3) |

| No | 8288 | 573 | 9.6 (8.5 to 10.9) | 10.6 (9.5 to 11.9) |

In unadjusted regression models compared with Mexican background, Puerto Rican background was associated with a 79% higher incidence rate for CKD (IRR 1.79; 95% CI, 1.33 to 2.40). This association was attenuated when sociodemographic characteristics were taken into account (IRR 1.35; 95% CI, 0.99 to 1.84), and further decreased after additional adjustment for clinical variables (IRR 1.02; 95% CI, 0.74 to 1.40) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Multivariable-adjusted risk of incident CKD by Hispanic/Latino background

| Predictor | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hispanic background | ||||

| Dominican | 1.03 (0.67 to 1.59) | 0.86 (0.55 to 1.35) | 0.82 (0.51 to 1.30) | 0.79 (0.50 to 1.25) |

| Central American | 0.97 (0.65 to 1.45) | 0.88 (0.58 to 1.34) | 0.87 (0.57 to 1.33) | 0.85 (0.56 to 1.30) |

| Cuban | 1.32 (0.94 to 1.85) | 1.00 (0.72 to 1.39) | 1.00 (0.70 to 1.41) | 0.92 (0.67 to 1.28) |

| Mexican | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent |

| Puerto Rican | 1.79 (1.33 to 2.40) | 1.35 (0.99 to 1.84) | 1.24 (0.90 to 1.70) | 1.02 (0.74 to 1.40) |

| South American | 0.79 (0.49 to 1.27) | 0.67 (0.42 to 1.07) | 0.73 (0.46 to 1.15) | 0.78 (0.49 to 1.24) |

| Other | 0.52 (0.25 to 1.08) | 0.66 (0.32 to 1.35) | 0.65 (0.31 to 1.33) | 0.55 (0.29 to 1.04) |

Values shown are incidence rate ratio (95% CI). Model 1: unadjusted; model 2: adjusted for age, sex, education, income, health insurance, U.S. born, and language; model 3: model 2plus smoking, systolic BP, HbA1c, C-reactive protein, and body mass index; and model 4: model 3 plus hypertension, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, ACEi/ARB, statin, calcium channel blocker, antiplatelet use, baseline eGFR, and albuminuria.

Unadjusted individual baseline predictors (CI for their IRR did not include 1) for developing CKD included: older age; female; less than high school education; low income; lack of health insurance coverage; place of birth inside the U.S.; diabetes; elevated BP; cardiovascular disease; high body mass index, HbA1c, C-reactive protein, and urine ACR; low eGFR; and use of cardioprotective medication (ACEi/ARB, statin, calcium channel blocker, and antiplatelet) (Table 4). Baseline multivariable predictors (CI for their IRR did not include 1) for incident CKD included the presence of systolic BP >140 mm Hg or diastolic BP >90 mm Hg (IRR 1.64; 95% CI, 1.08 to 2.48), HbA1c (IRR 1.10; 95% CI, 1.01 to 1.19, per one percentage point increase), eGFR (IRR 0.98; 95% CI, 0.97 to 0.98, per 1 ml/min per 1.73 m2 increase), urine ACR (IRR 3.24; 95% CI, 2.66 to 3.96, per one log-transformed mg/g increase), and ACEi/ARB use (IRR 1.48; 95% CI, 1.17 to 1.88).

Table 4.

Baseline individual and multivariable predictors of incident CKD after a median of 5.9 years of follow-up

| Baseline Variable | Incidence Rate Ratio (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|

| Individual Predictors | Multivariable Predictorsa | |

| Age (per 1 yr increase) | 1.05 (1.04 to 1.05)b | 1.00 (0.99 to 1.02) |

| Women (versus men) | 1.32 (1.04 to 1.68)b | 0.89 (0.68 to 1.16) |

| Education ≥high school (versus <high school) | 0.60 (0.47 to 0.77 )b | 0.81 (0.62 to 1.06) |

| Income ≥$20,000 (versus <$20,000) | 0.72 (0.55 to 0.94)b | 1.00 (0.77 to 1.30) |

| English language (versus Spanish) | 0.90 (0.68 to 1.21) | — |

| Language acculturation subscale (per 1 unit increase) | 0.90 (0.81 to 1.00) | — |

| Health insurance (yes versus no) | 1.34 (1.07 to 1.67)b | 0.92 (0.72 to 1.17) |

| Born in the U.S. (yes versus no) | 0.50 (0.36 to 0.69)b | 0.73 (0.50 to 1.06) |

| ≥10 yr in the U.S. (versus <10 yr) | 1.27 (0.93 to 1.73) | — |

| Diabetes | 3.58 (2.84 to 4.51)b | 1.16 (0.86 to 1.57) |

| SBP >140 or DBP >90 mm Hg (yes versus no) | 2.82 (2.17 to 3.65)b | 1.64 (1.08 to 2.48)b |

| Cardiovascular disease | 2.89 (2.12 to 3.93)b | 1.05 (0.72 to 1.52) |

| Smoking, | 1.44 (1.08 to 1.91) | 1.03 (0.77 to 1.39) |

| Past (versus never) | ||

| Current (versus never) | 1.22 (0.91 to 1.63) | 1.21 (0.85 to 1.71) |

| Physical activity | 1.40 (0.97 to 2.03) | 1.43 (0.96 to 2.12) |

| Less than ideal (versus inactive) | ||

| Ideal (versus inactive) | 0.74 (0.57 to 0.95)b | 1.14 (0.86 to 1.52) |

| SBP (per 1 mm Hg increase) | 1.02 (1.02 to 1.03)b | 0.99 (0.98 to 1.00) |

| Body mass index (per 1 kg/m2 increase) | 1.04 (1.02 to 1.05)b | 1.00 (0.98 to 1.02) |

| LDL-cholesterol (per 1 mg/dl increase) | 1.00 (1.00 to 1.00) | — |

| HDL-cholesterol (per 1 mg/dl increase) | 1.01 (1.00 to 1.02) | — |

| HbA1c (per 1% increase) | 1.38 (1.32 to 1.45)b | 1.10 (1.01 to 1.19)b |

| eGFR-creatinine/cystatin-C (per 1 ml/min per 1.73 m2 increase) | 0.97 (0.96 to 0.97)b | 0.98 (0.97 to 0.98)b |

| Urine ACR (per 1 log-mg/g increase) | 3.69 (3.11 to 4.37)b | 3.24 (2.66 to 3.96)b |

| C-reactive protein (per 1 mg/L increase) | 1.02 (1.01 to 1.03)b | 1.01 (1.00 to 1.01)b |

| ACEi/ARB use (yes versus no) | 4.10 (3.28 to 5.12)b | 1.48 (1.17 to 1.88)b |

| Statin use (yes versus no) | 3.18 (2.43 to 4.17)b | 1.04 (0.80 to 1.36) |

| Calcium channel blocker use (yes versus no) | 3.71 (2.70 to 5.11)b | 1.22 (0.84 to 1.77) |

| Antiplatelet use (yes versus no) | 5.03 (3.17 to 7.98)b | 1.47 (0.84 to 2.57) |

SBP, systolic BP; DBP, diastolic BP.

Adjusted for Hispanic/Latino background and other variables listed.

P<0.05.

Discussion

We found that incident CKD rates vary by Hispanic/Latino background, and this disparity may be in part attributed to differences in sociodemographic factors. Incident CKD rates were higher among persons of Puerto Rican background, older individuals, women, and those with diabetes, hypertension, or cardiovascular disease. Risk factors for incident CKD included elevated baseline HbA1c and albuminuria, and lower eGFR.

In a cross-sectional analysis of this cohort at baseline, we previously reported higher prevalence of CKD among U.S. adults of Puerto Rican background compared with other Hispanic/Latino background groups.2 In this study, which is the first to evaluate incident CKD in a large and diverse population-based cohort of U.S. Hispanics/Latinos, we report the highest rates of new-onset CKD among Puerto Ricans. A higher burden of kidney disease has been previously observed among Puerto Ricans. In a cross-sectional study from the Hispanic Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, Rodriguez et al.17 found that Puerto Ricans and Cuban Americans were more likely to have low estimated creatinine clearance (<60 ml/min per 1.73 m2) compared with Mexican Americans after adjustment for demographic and clinical characteristics. In longitudinal study using data from the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis, Peralta et al.14 found that compared with whites, Dominicans and Puerto Ricans had faster rates of eGFR decline, whereas Mexicans/Central Americans and South Americans had similar rates. However, this study did not report incident CKD by Hispanic/Latino background group, likely due to the small number of events and because a repeat measure of albuminuria was not available. There are limited data regarding whether incident ESKD rates in the U.S. differ by Hispanic/Latino background group because the U.S. Renal Data System does not collect this information. However, in an international study, incident ESKD rates in Puerto Rico in 2004 were more than twofold higher than the overall rates observed in 20 countries in Latin America (337 versus 147 per million population), and by 2016 the incident ESKD rate in Puerto Rico had increased to 419 per million population.18,19

The increased risk of incident CKD in Puerto Ricans was largely explained by sociodemographic factors and acculturation. Compared with other Hispanic/Latino background groups, Puerto Ricans were more likely to be U.S. born and use English as a primary language. The relationship between acculturation and health outcomes is complex. Whereas individuals with higher acculturation may have higher rates of health insurance, higher levels of acculturation have been found to be associated with unhealthy behaviors, such as increased tobacco use, unhealthy diet, and lower physical activity.20 Consistent with this, we found that individuals of Puerto Rican background had higher prevalence of traditional CKD risk factors (i.e., diabetes, hypertension, obesity, and smoking), which has also been reported in other studies.21–23

Of note, in a cross-sectional analysis of HCHS/SOL baseline data, Lora et al.24 did not find a significant association between language or place of birth and prevalent CKD. Future work is needed to better understand the complicated interplay between acculturation and incident CKD.

The observed variability in incident CKD risk across background groups reinforces the concept that Hispanic/Latinos are a heterogeneous population. Furthermore, our findings have important public health implications for the implementation of CKD prevention strategies, and suggest the need to evaluate culturally tailored interventions. For example, for certain individuals, access to healthcare and language may be the major barriers, whereas for others a focus on cultural factors that influence beliefs and knowledge may be more relevant.20,25

Future studies are needed to evaluate the role of genetic factors in CKD incidence among Hispanics/Latinos. In black individuals, apo A-1 (APOL1) has been associated with increased risk for CKD progression.26 This is particularly relevant to the Hispanic/Latino population because the frequency of the APOL1 allele varies significantly by Hispanic/Latino background. In a recent HCHS/SOL study, Kramer et al. reported a higher prevalence of two copies of the APOL1 risk alleles (versus zero or one copy) among Hispanics/Latinos of Caribbean background (Puerto Rican, Dominican, or Cuban), compared with those of mainland background (Mexican, Central, or South American). In addition, the presence of two APOL1 variants was significantly associated with albuminuria and/or low eGFR.27

We also found that elevated baseline levels of HbA1c, albuminuria, and eGFR were significantly associated with development of CKD during the follow-up period. These findings are similar to prior studies in non-Hispanic populations. In the Framingham Offspring Study, predictors of new-onset kidney disease included age, body mass index, diabetes, and smoking.10 Our finding regarding the higher risk of incident CKD among individuals reporting ACEi/ARB use at baseline was likely due to confounding by indication, in that these individuals may have had a condition (e.g., diabetes or albuminuria) that prompted the initiation of these agents.

The major strength of this study was the large, diverse community sample, providing the opportunity to establish population estimates of incident CKD among Hispanics/Latinos, a population that is at high risk for ESKD. Our findings should be considered with the following limitations. First, the classification of persons with incident CKD was on the basis of single measurements of serum creatinine, cystatin C, and urine albumin. Second, the GFR estimating equation used has not been validated in Hispanics/Latinos. Third, we did not account for death as a competing risk for incident CKD, although the death rates in HCHS/SOL are low. Fourth, the study did not include non-Hispanics. However, the observed incident CKD rates in this study are consistent with the rates reported in the Centers for Disease Control Surveillance Data/Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities.28,29 Lastly, as described above, the HCHS/SOL cohort was selected through a probability sample of four communities (Chicago, IL; Miami, FL; Bronx, NY; and San Diego, CA), which allows the estimation of disease incidence and baseline risk factors that target population rather than the entire nation. Therefore, it is possible that our results are influenced by regional differences in CKD risk factors, as is known to be the case in ESKD.30 However, the HCHS/SOL sampling design is superior to the convenience samples that are typically used in epidemiologic cohort studies. Moreover, the sociodemographic characteristics of HCHS/SOL participants are similar to those reported by the U.S. National Center for Health Statistics.31 Incident CKD rates vary by Hispanic/Latino background and this disparity may be in part attributed to differences in sociodemographic factors. Public heath efforts to reduce the burden of CKD in Hispanics/Latinos should focus on culturally tailored intervention for the prevention and control of risk factors, including diabetes and hypertension.

Disclosures

Dr. Daviglus reports grants from National Institutes of Health (NIH), during the conduct of the study. Dr. Franceschini reports grants from NIH, during the conduct of the study. Dr. Lash reports grants from NIH, during the conduct of the study. Dr. Loop reports other from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI), during the conduct of the study. Dr. Ricardo reports grants from NIH, during the conduct of the study. Dr. Talavera reports grants from NIH, during the conduct of the study. Dr. Toth-Manikowski reports grants from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Disease (NIDDK).

Funding

The HCHS/SOL was carried out as a collaborative study supported by contracts from the NHLBI to the University of North Carolina (grant N01 HC65233), University of Miami (grant N01 HC65234), Albert Einstein College of Medicine (grant N01 HC65235), Northwestern University (grant N01 HC65236), and San Diego State University (grant N01 HC65237). The following institutes, centers, or offices contribute to the HCHS/SOL through a transfer of funds to the NHLBI: the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities, the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communications Disorders, the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, the NIDDK, the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, and the Office of Dietary Supplements. Dr. Franceschini is supported by NIH grants DK117445012765 and HL140385, and NIMHD grant R01-MD012765. Dr. Lash is funded by NIDDK grant K24 DK092290. Dr. Ricardo is funded by NIDDK grant R01 DK118736.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the staff and participants of the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos (HCHS/SOL) for their important contributions.

A complete list of staff and investigators has been provided by previously11 and is also available on the study website (http://www.cscc.unc.edu/hchs/).

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.jasn.org.

Supplemental Material

This article contains the following supplemental material online at http://jasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1681/ASN.2019101008/-/DCSupplemental.

Supplemental Table 1. Baseline characteristics of HCHS/SOL participants.

Supplemental Table 2. Baseline and follow-up visit characteristics of individuals who developed CKD.

Supplemental Table 3. eGFR and albuminuria categories among U.S. Hispanic/Latinos with incident CKD.

References

- 1.Saran R, Robinson B, Abbott KC, Agodoa LYC, Bragg-Gresham J, Balkrishnan R, et al.: US Renal Data System 2018 Annual Data Report: Epidemiology of Kidney Disease in the United States. Am. J. Kidney Dis 73: A7–A8, 2019. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2019.01.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ricardo AC, Flessner MF, Eckfeldt JH, Eggers PW, Franceschini N, Go AS, et al.: Prevalence and correlates of CKD in Hispanics/Latinos in the United States. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 10: 1757–1766, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.U.S. Census Bureau: Facts for Figures: Hispanic Heritage Month 2017, 2017. Available at: https://www.census.gov/newsroom/facts-for-features/2017/hispanic-heritage.html. Accessed October 4, 2017

- 4.Bryc K, Durand EY, Macpherson JM, Reich D, Mountain JL: The genetic ancestry of African Americans, Latinos, and European Americans across the United States. Am J Hum Genet 96: 37–53, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Daviglus ML, Talavera GA, Avilés-Santa ML, Allison M, Cai J, Criqui MH, et al.: Prevalence of major cardiovascular risk factors and cardiovascular diseases among Hispanic/Latino individuals of diverse backgrounds in the United States. JAMA 308: 1775–1784, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schneiderman N, Llabre M, Cowie CC, Barnhart J, Carnethon M, Gallo LC, et al.: Prevalence of diabetes among Hispanics/Latinos from diverse backgrounds: The Hispanic community health study/study of Latinos (HCHS/SOL). Diabetes Care 37: 2233–2239, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Prevalence of diagnosed diabetes National Diabetes Statistics Report data & statistics, Atlanta, Georgia, Diabetes CDC, 2018. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/data/statistics-report/diagnosed.html. Accessed December 5, 2018 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sorlie PD, Allison MA, Avilés-Santa ML, Cai J, Daviglus ML, Howard AG, et al.: Prevalence of hypertension, awareness, treatment, and control in the Hispanic community health study/study of Latinos. Am J Hypertens 27: 793–800, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Office of Minority Health: Obesity and Hispanic Americans, 2018. Available at: https://minorityhealth.hhs.gov/omh/browse.aspx?lvl=4&lvlid=70. Accessed December 5, 2019

- 10.Lavange LM, Kalsbeek WD, Sorlie PD, Avilés-Santa LM, Kaplan RC, Barnhart J, et al.: Sample design and cohort selection in the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos. Ann Epidemiol 20: 642–649, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sorlie PD, Avilés-Santa LM, Wassertheil-Smoller S, Kaplan RC, Daviglus ML, Giachello AL, et al.: Design and implementation of the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos. Ann Epidemiol 20: 629–641, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marin G, Sabogal F, Marin BV, Otero-Sabogal R, Perez-Stable EJ: Development of a short acculturation scale for Hispanics. Hisp J Behav Sci 9: 183–205, 1987 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Inker LA, Schmid CH, Tighiouart H, Eckfeldt JH, Feldman HI, Greene T, et al.; CKD-EPI Investigators: Estimating glomerular filtration rate from serum creatinine and cystatin C [published correction appears in N Engl J Med 367: 2060, 2012]. N Engl J Med 367: 20–29, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Peralta CA, Katz R, DeBoer I, Ix J, Sarnak M, Kramer H, et al.: Racial and ethnic differences in kidney function decline among persons without chronic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 22: 1327–1334, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Peralta CA, Bibbins-Domingo K, Vittinghoff E, Lin F, Fornage M, Kopp JB, et al.: APOL1 genotype and race differences in incident albuminuria and renal function decline. J Am Soc Nephrol 27: 887–893, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thyagarajan B, Howard AG, Durazo-Arvizu R, Eckfeldt JH, Gellman MD, Kim RS, et al.: Analytical and biological variability in biomarker measurement in the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos. Clin Chim Acta 463: 129–137, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rodriguez RA, Hernandez GT, O’Hare AM, Glidden DV, Pérez-Stable EJ: Creatinine levels among Mexican Americans, Puerto Ricans, and Cuban Americans in the Hispanic Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Kidney Int 66: 2368–2373, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cusumano A, Garcia-Garcia G, Di Gioia C, Hermida O, Lavorato C, Carreño CA, et al.: End-stage renal disease and its treatment in Latin America in the twenty-first century. Ren Fail 28: 631–637, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Registro Latinoamericano de Diálisis y Trasplante Renal | SLANH. Available at: https://slanh.net/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/INFORME-2018.pdf. Accessed December 7, 2018

- 20.Lora CM, Gordon EJ, Sharp LK, Fischer MJ, Gerber BS, Lash JP: Progression of CKD in Hispanics: Potential roles of health literacy, acculturation, and social support. Am J Kidney Dis 58: 282–290, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mattei J, Tamez M, Ríos-Bedoya CF, Xiao RS, Tucker KL, Rodríguez-Orengo JF: Health conditions and lifestyle risk factors of adults living in Puerto Rico: A cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 18: 491, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pérez-Cardona C, Pérez-Perdomo R: Prevalence and associated factors of diabetes mellitus in Puerto Rican adults: Behavioral risk factor surveillance system, 1999. P R Health Sci J 20: 147–155, 2001 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Giambrone AE, Gerber LM, Rodriguez-Lopez JS, Trinh-Shevrin C, Islam N, Thorpe LE: Hypertension prevalence in New York city adults: Unmasking undetected racial/ethnic variation, NYC HANES 2004. Ethn Dis 26: 339–344, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lora CM, Ricardo AC, Chen J, Cai J, Flessner M, Moncrieft A, et al.: Acculturation and chronic kidney disease in the Hispanic community health study/study of Latinos (HCHS/SOL). Prev Med Rep 10: 285–291, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barron F, Hunter A, Mayo R, Willoughby D: Acculturation and adherence: Issues for health care providers working with clients of Mexican origin. J Transcult Nurs 15: 331–337, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Parsa A, Kao WH, Xie D, Astor BC, Li M, Hsu CY, et al.; AASK Study Investigators; CRIC Study Investigators: APOL1 risk variants, race, and progression of chronic kidney disease. N Engl J Med 369: 2183–2196, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kramer HJ, Stilp AM, Laurie CC, Reiner AP, Lash J, Daviglus ML, et al.: African ancestry-specific alleles and kidney disease risk in Hispanics/Latinos. J Am Soc Nephrol 28: 915–922, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention : Chronic Kidney Disease Surveillance System. Available at: https://nccd.cdc.gov/CKD. Accessed January 7, 2019

- 29.Bash LD, Coresh J, Köttgen A, Parekh RS, Fulop T, Wang Y, et al.: Defining incident chronic kidney disease in the research setting: The ARIC Study. Am J Epidemiol 170: 414–424, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.United States Renal Data System : 2018. Annual data report. Available at: https://www.usrds.org/adr.aspx. Accessed January 15, 2020

- 31.Dominguez K, Penman-Aguilar A, Chang M-H, Moonesinghe R, Castellanos T, Rodriguez-Lainz A, et al.; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC): Vital signs: Leading causes of death, prevalence of diseases and risk factors, and use of health services among Hispanics in the United States - 2009-2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 64: 469–478, 2015 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.