LETTER

The currently unfolding coronavirus pandemic threatens health systems and economies worldwide. The spread of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) and the associated disease coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has initially been limited to China. However, the virus has now been detected in more than 100 countries outside China, and major outbreaks are ongoing in the United States, Italy, and Spain. At present, our antiviral arsenal offers little protection against SARS-CoV-2, although recent progress has been reported (1), and novel antivirals are urgently needed to mitigate the COVID-19 health crisis.

The SARS-CoV-2 spike protein (S) is inserted into the viral envelope and mediates viral entry into cells. For this, the S protein depends on the cellular enzyme transmembrane protease serine 2 (TMPRSS2), which cleaves and thereby activates the S protein (2). SARS-CoV (3–5) and other coronaviruses (6, 7) also use TMPRSS2 for S protein activation, and the protease is expressed in SARS-CoV target cells throughout the human respiratory tract (8). Moreover, TMPRSS2 is required for spread of SARS-CoV and Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) in rodent models (9, 10) but is dispensable for development and homeostasis in mice (11). Thus, TMPRSS2 constitutes an attractive drug target.

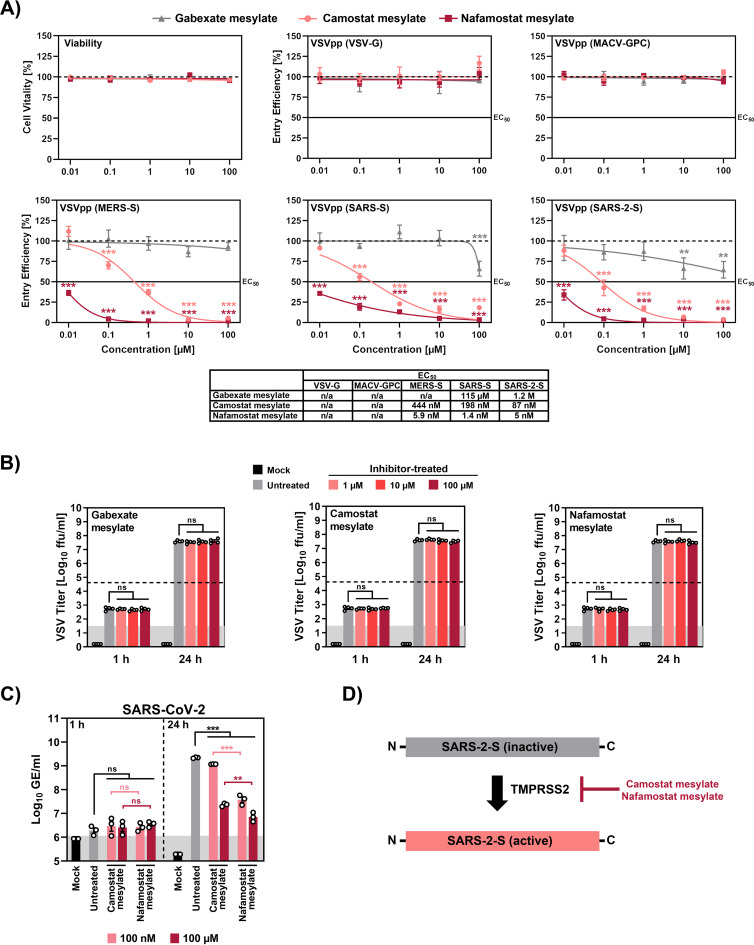

Recent work shows that camostat mesylate (NI-03), a serine protease inhibitor active against TMPRSS2 and employed for treatment of pancreatitis in Japan, inhibits SARS-CoV-2 infection of human lung cells (2). The suitability of camostat mesylate for treatment of COVID-19 is currently being evaluated in a clinical trial (12), but it is unclear whether compound concentrations can be attained in the lung that are sufficient to suppress viral spread. In the absence of this information, testing of other serine protease inhibitors for blockade of SARS-CoV-2 entry is an important task. For this, we tested gabexate mesylate (FOY) and nafamostat mesylate (Futhan) (13) along with camostat mesylate for inhibition of SARS-CoV-2 infection of lung cells. All compounds are approved for human use in Japan, and nafamostat mesylate inhibits TMPRSS2-dependent host cell entry of MERS-CoV (14). A comparison of the antiviral activities of the three compounds revealed that none interfered with cell viability or with host cell entry mediated by the glycoproteins of vesicular stomatitis virus or Machupo virus (Fig. 1A), which served as negative controls. Gabexate mesylate slightly inhibited SARS-CoV-2 S-driven host cell entry while camostat mesylate robustly suppressed entry (Fig. 1A). Notably, nafamostat mesylate, which is FDA approved for indications unrelated to coronavirus infection, inhibited SARS-CoV-2 S-mediated entry into host cells with roughly 15-fold-higher efficiency than camostat mesylate, with a 50% effective concentration [EC50] in the low-nanomolar range (Fig. 1A). Moreover, nafamostat mesylate blocked SARS-CoV-2 infection of human lung cells with markedly higher efficiency than camostat mesylate while both compounds were not active against vesicular stomatitis virus infection, as expected (Fig. 1B to D). In light of the global impact of COVID-19 on human health, the proven safety of nafamostat mesylate, and its increased antiviral activity compared to camostat mesylate, we argue that this compound should be evaluated in clinical trials as a COVID-19 treatment.

FIG 1.

Nafamostat mesylate inhibits SARS-CoV-2 infection of lung cells in the nanomolar range. The lung-derived human cell line Calu-3 was incubated with the indicated concentrations of the indicated serine protease inhibitors, and (A) either cell viability was measured or the cells were inoculated with vesicular stomatitis virus reporter particles pseudotyped with the indicated viral glycoproteins. The efficiency of viral entry was determined at 16 h postinoculation by measuring luciferase activity in cell lysates. The 50% effective dose values are indicated below the graphs. In parallel, cells exposed to serine protease inhibitors were infected with replication-competent vesicular stomatitis virus encoding green fluorescent protein (B) or infected with SARS-CoV-2 (C), and infection efficiency was quantified by focus formation assay and by measuring genome copies via quantitative RT-PCR, respectively. A scheme of how camostat and nafamostat mesylate block activation of SARS-2-S is shown in panel D. The average from three independent experiments is shown in panels A and C while the average from four independent experiments is presented in panel B. For panels A to C, statistical significance was tested by two-way analysis of variance with Dunnett’s posttest. In addition, statistical significance of differences between SARS-CoV-2 genome equivalents at identical concentrations of camostat or nafamostat mesylate was tested by one-way analysis of variance with Sidak’s posttest. Abbreviations: VSV-G, vesicular stomatitis virus glycoprotein, MACV-GPC, Machupo virus glycoprotein complex; MERS-S, Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus spike glycoprotein; SARS-S, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus spike glycoprotein; SARS-2-S, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 spike glycoprotein.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was supported by BMBF (RAPID Consortium, 01KI1723D and 01KI1723A to S.P. and C.D.).

REFERENCES

- 1.Wang M, Cao R, Zhang L, Yang X, Liu J, Xu M, Shi Z, Hu Z, Zhong W, Xiao G. 2020. Remdesivir and chloroquine effectively inhibit the recently emerged novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) in vitro. Cell Res 30:269–271. doi: 10.1038/s41422-020-0282-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hoffmann M, Kleine-Weber H, Schroeder S, Krüger N, Herrler T, Erichsen S, Schiergens TS, Herrler G, Wu N-H, Nitsche A, Müller MA, Drosten C, Pöhlmann S. 2020. SARS-CoV-2 cell entry depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and is blocked by a clinically proven protease inhibitor. Cell 181:271–280.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.02.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Glowacka I, Bertram S, Müller MA, Allen P, Soilleux E, Pfefferle S, Steffen I, Tsegaye TS, He Y, Gnirss K, Niemeyer D, Schneider H, Drosten C, Pöhlmann S. 2011. Evidence that TMPRSS2 activates the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus spike protein for membrane fusion and reduces viral control by the humoral immune response. J Virol 85:4122–4134. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02232-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Matsuyama S, Nagata N, Shirato K, Kawase M, Takeda M, Taguchi F. 2010. Efficient activation of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus spike protein by the transmembrane protease TMPRSS2. J Virol 84:12658–12664. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01542-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shulla A, Heald-Sargent T, Subramanya G, Zhao J, Perlman S, Gallagher T. 2011. A transmembrane serine protease is linked to the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus receptor and activates virus entry. J Virol 85:873–882. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02062-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gierer S, Bertram S, Kaup F, Wrensch F, Heurich A, Krämer-Kühl A, Welsch K, Winkler M, Meyer B, Drosten C, Dittmer U, von Hahn T, Simmons G, Hofmann H, Pöhlmann S. 2013. The spike protein of the emerging betacoronavirus EMC uses a novel coronavirus receptor for entry, can be activated by TMPRSS2, and is targeted by neutralizing antibodies. J Virol 87:5502–5511. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00128-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shirato K, Kawase M, Matsuyama S. 2013. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection mediated by the transmembrane serine protease TMPRSS2. J Virol 87:12552–12561. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01890-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bertram S, Heurich A, Lavender H, Gierer S, Danisch S, Perin P, Lucas JM, Nelson PS, Pöhlmann S, Soilleux EJ. 2012. Influenza and SARS-coronavirus activating proteases TMPRSS2 and HAT are expressed at multiple sites in human respiratory and gastrointestinal tracts. PLoS One 7:e35876. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Iwata-Yoshikawa N, Okamura T, Shimizu Y, Hasegawa H, Takeda M, Nagata N. 2019. TMPRSS2 contributes to virus spread and immunopathology in the airways of murine models after coronavirus infection. J Virol 93:e01815-18. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01815-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhou Y, Lu K, Pfefferle S, Bertram S, Glowacka I, Drosten C, Pöhlmann S, Simmons G. 2010. A single asparagine-linked glycosylation site of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus spike glycoprotein facilitates inhibition by mannose-binding lectin through multiple mechanisms. J Virol 84:8753–8764. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00554-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim TS, Heinlein C, Hackman RC, Nelson PS. 2006. Phenotypic analysis of mice lacking the Tmprss2-encoded protease. Mol Cell Biol 26:965–975. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.3.965-975.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kupferschmidt K. 2 April 2020. These drugs don’t target the coronavirus—they target us. Science, New York, NY: https://www.sciencemag.org/news/2020/04/these-drugs-don-t-target-coronavirus-they-target-us. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fujii S, Hitomi Y. 1981. New synthetic inhibitors of C1r, C1 esterase, thrombin, plasmin, kallikrein and trypsin. Biochim Biophys Acta 661:342–345. doi: 10.1016/0005-2744(81)90023-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yamamoto M, Matsuyama S, Li X, Takeda M, Kawaguchi Y, Inoue J-I, Matsuda Z. 2016. Identification of nafamostat as a potent inhibitor of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus S protein-mediated membrane fusion using the split-protein-based cell-cell fusion assay. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 60:6532–6539. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01043-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]