Abstract

Objective:

It is known that job satisfaction and quality of life influence nurses’ intention to resign from their jobs. However, health-care systems should examine all the possible factors that contribute to nurse turnover to retain them for the long term. To this purpose, this study further explores the aspects that affect the intention of nurses who work in Saudi Arabia to leave their current jobs.

Methods:

A sample of 318 staff nurses working in two public hospitals in Saudi Arabia was surveyed in this cross-sectional study. A questionnaire was used to assess job satisfaction, stress, quality of life, and intention of recruited nurses to leave their current jobs. Data were collected between April and May 2018.

Results:

Quality of life dimensions, such as physical and psychological health, predict nurses’ intention to resign from their current workplaces. We found that being single or of Filipino or Indian origin, working in the medical and surgical department, or having a low monthly gross salary is correlated with a high intention to leave.

Conclusion:

The results present a unique theoretical underpinning that expands on the previous knowledge and literature on the factors that affect nurses’ intent to leave their organizations. The findings of this study can be used as a guide to establish human resource policies toward satisfying nurses’ needs and improving job satisfaction and quality of life to promote retention.

Keywords: Health-care system, intention to leave, job satisfaction, nurses, stress, quality of life

Introduction

The intention of nurses to leave their current jobs has become a global issue that has been investigated over the past decade. Turnover intention is one of the main difficulties that several health-care organizations face, leading to inadequate nurse staffing, elevated work stress due to increased workloads,[1] job dissatisfaction, and productivity, and intent to resign and switch to other health-care organizations. Higher turnover is also damaging to patients’ well-being.[2] For instance, a previous study mentioned that a higher nurse turnover promotes longer hospitalization and increased number of medical errors.[3] Hence, it has a negative effect on the patients’ need for appropriate provision of high-quality care. Turnover intention could also incur higher costs caused by the need to replace employees, recruit and train temporary staff, and ensure service quality.

Health-care systems around the world are already plagued by nursing staff shortages. For example, Heinen found that nurses’ intention to leave influences their turnover, which varies from 5 to 17% in European countries.[4] In one study in Lebanon (n = 857), 62.5% of the nurses disclosed their intention to leave their current profession over the coming 1–3 years.[3] Several aspects, such as job satisfaction[4,5] and quality of life (QoL),[6] have been reported to be associated with nurses’ intention to leave. The factors that contribute to job satisfaction include salaries, promotions, and professional improvement opportunities.[7,8] In addition, work stress can negatively affect employee productivity and work satisfaction, which may lead to an individual’s intention to leave the nursing profession.[8] One recent study conducted in Australia showed a remarkable association between staff turnover and lower QoL.[9] Another study conducted in Iran indicated that a high QoL can lead to improved work performance and job satisfaction.[10] Furthermore, in Iran, it has been reported that nurses tend to have an average QoL in clinical health-care settings.[10] Ibrahim et al.[11] suggested that a poor QoL can lead to problems later on, including job dissatisfaction and higher job turnover. It is most likely that a poor nursing QoL in the health-care delivery system can have a negative impact on patient safety.

These issues are also a great concern in Saudi Arabia. Here, the nursing workforce relies mainly on expatriate nurses, with only 18% of the total workforce being composed of Saudi nurses.[12] A retrospective study identifying nurses who were recruited and who then resigned from a Saudi Government Hospital (January 2006–October 2010) found that the nursing shortage was significantly related to high nurse turnover.[13] It is almost certain that a shortage of nurses in a hospital leads to a lower quality of patient care and poorer work performance. In this context, the Saudi government implemented a “Saudi Health-care National Transformation Program (NTP)-2020” that provides a well-equipped hospital, governance improvement in the quality of health-care services, especially among health-care professionals. However, it is reported that NTP 2020 is experiencing challenges in implementation (e.g., a lack of administrative support, unavailable hospital funds, unclear hospital goals, and conflicting health-care objectives). These issues might affect nurses’ productivity and the successful implementation of Saudi health care.[14] The study of Altakroni et al.[15] investigated the productivity of Saudi female nurses working in the Saudi Arabian health-care system and revealed that they experienced lower work productivity due to a lack of work–life balance and cultural issues associated with being married. This lower productivity might mean decreased patient outcomes, patient service efficiency, and quality of patient care. Thus, hospital administrators may need to reflect on improving their systems based on work productivity.

Meanwhile, another recent study focused on expatriate nurses working in Saudi Arabia, where these nurses are employed on yearly contracts.[16] If their contracts are not renewed, this situation can lead to turnover and increased mental burden or create job insecurity and fear of litigation, all of which affect patient safety and quality of care.[16] This further increases the risk of remaining nurses quitting their jobs or moving to less stressful work environments. Organizational policies for overcoming the challenges facing nursing recruitment and retention in Saudi Arabia were emphasized as significant objectives in Vision 2030.[17] Another goal of Vision 2030 is revitalize career-focused educational institutions to increase the number of Saudi health-care professionals and encourage them to join the nursing profession.[17] However, the above vision has only been proven to be successful in other sectors, such as the educational system, and not the Saudi health-care system,[17] which has a constant dearth of Saudi health-care professionals.[18]

In addition, the majority of the health-care personnel in Saudi Arabia consists of expatriates,[1] who have been reported to experience difficulty adjusting to Saudi culture, this being one of the reasons why they tend to leave the country. With a short length of employment, it becomes challenging to maintain a secure health-care workflow that draws on well-developed levels of vital care expertise because extra effort is required to train and build competence among newly recruited nurses.[19] To retain nursing staff, health-care systems should examine the factors that contribute to nurses’ turnover and intention to leave. However, existing studies have not examined how health-care organizations in the KSA respond to this challenge. Furthermore, very little attention has been paid to the reasons behind nurses’ intention to leave their current occupation, especially among expatriate nurses working in Saudi Arabia, a gap in knowledge that this study addresses.

Methods

Study design

This study utilized a cross-sectional design to explore the factors affecting nurses’ intention to leave their current jobs in Saudi Arabia.

Settings and sample

We used a convenience sampling technique in two public hospitals in Saudi Arabia. Hospital A (staff nurses = 187; bed capacity = 225) and Hospital B (staff nurses = 246; bed capacity = 250) are secondary public hospitals located in the Riyadh Province of Saudi Arabia. Each hospital offers various medical and surgical services. The inclusion criteria were as follows: Male or female nurses who provided direct patient care, who had been employed as a nurse in Saudi Arabia for more than 6 months, and who voluntarily consented to participate. Unit managers and clinical resource nurses were excluded because they mandate policy, systems, procedures, and organizational climates. They supervise staff nurses and are not directly involved in patient care.

A total of 433 staff nurses from the two hospitals were invited to participate. However, only 388 respondents met the inclusion criteria and consented to answer the survey. Sixty-eight surveys had incomplete data; therefore, only 318 respondents were included in the final analysis.

Ethical considerations

The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Ministry of Health in Saudi Arabia (IRB log number 18-147E). Information about the study was provided to the nurses who met the selection criteria. The researchers adhered to ethical standards (e.g., privacy, confidentiality, self-determination, and autonomy). The respondents were free to withdraw from participation at any time without negatively impacting their involvement. A cover letter presenting the survey and information regarding the study’s purpose, potential data use, and data collection methods was provided to the participants.

Study variables

In this study, the dependent variable was the intention to leave the current nursing job, while job satisfaction and the QoL were selected as the independent variables. Specifically, these variables were measured using the Generic Job Satisfaction Scale (GJSS),[20,21] and the World Health Organization QoL (WHOQOL-BREF) scale.[22-25] It was hypothesized that the above-mentioned variables would influence the nurses’ intentions to leave.

The questionnaire

A self-administered structured questionnaire was used for data collection. The questionnaire had five sections, described as follows.

Demographic and work-related characteristics

Part one of the questionnaire included the respondents’ demographic and work-related characteristics, including age, gender, marital status, educational level, total years of experience at the current hospital, area of practice, nationality, salary, working hours per week, and total years of experience as a nurse.

Intention to leave current job

Part two of the questionnaire evaluated the intention to leave the organization (turnover) using the six-item Turnover Intention Scale (TIS-6).[26] The respondents were asked to rate each item using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). A high mean score indicated a high intention to leave. The shortened version of the TIS-6 has reported turnover reliability scores of α = 0.80,[26] indicating good reliability. In this study, the Cronbach’s α was 0.86.

Job satisfaction

Part three of the survey evaluated the employee’s feelings or reactions toward certain aspects of his or her job using the GJSS.[20] This 10-item scale measures job-related satisfaction, including job stress, boredom, isolation, and danger of illness or injury. The GJSS uses a 5-point Likert-type scale (ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree). An overall summation score was computed for the entire scale, on which a high score indicates high job satisfaction. The reliability of this scale (Cronbach’s α = 0.77) was acceptable. In addition, the Arabic version of the scale (Cronbach’s α = 0.79) was also considered reliable and valid for assessing nurses’ job satisfaction.[21] In this study, the Cronbach’s α was 0.84.

Stress

Part four of the survey evaluated the stress level perceived by the respondents using the PSS-14.[27] The PSS-14 measures the perception of what is considered to be stressful in the daily life of each respondent and it contains seven positively worded stress items and seven negatively worded counter stress items. The included statements are rated on a 5-point Likert scale (ranging from 0 = never to 4 = very often). A high mean score suggests that the individual is stressed. The Cronbach’s α coefficient has been previously reported to be 0.81,[27] exhibiting remarkable validity and reliability.[28] In this study, the Cronbach’s alpha was 0.83.

Quality of life

Part five of the survey measured each individual’s perspective with regard to their value systems, culture, personal goals, standards, and concerns using the WHOQOL-BREF.[22] This scale contains 26 items that measure four broad domains: Physical health, psychological health, social relationships, and environment. The WHOQOL-BREF scale produces a QoL profile and four domain scores. A high score indicates a high QoL level. The previous studies[23,24] have reported Cronbach’s α coefficients of 0.83 and 0.96, while the Arabic version of the scale also confirms the validity and reliability of the scale.[25] In this study, the Cronbach’s alpha was 0.84.

The use of the questionnaire was permitted by the copyright holder of the tool through email. The questionnaire was pilot tested among staff nurses in different hospital settings and with the same demographic characteristics to create a representative sample for the study.

Data collection

We collected data between April and May 2018. Before this, the researchers asked permission from the respective heads of the relevant health-care departments. Once permission to conduct the study was obtained, all nurses that were conveniently selected were included in the survey and asked if they would be interested in participating. Once they agreed, the researchers distributed the questionnaires to the nurses. Before the respondents completed the questionnaire, the researchers provided the respondents a short introduction about the study’s purpose, clarified terms used in the questionnaire, and answered the respondents’ queries. After answering the questionnaire, the participants were asked to submit their responses to the researchers.

Data analysis

The SPSS software (version 24) was utilized for data analysis. Descriptive statistics were used to determine the respondents’ demographic and work-related characteristics. The mean and standard deviation (SD) were calculated to assess job satisfaction, intention to leave, and job stress among staff nurses. The differences in the respondents’ intention to leave by nationality and clinical area were determined using ANOVA; t-tests were performed to compare the intention to leave among the respondents when grouped according to hospital, gender, and marital status. The relationship between intention to leave and age, working hours/week, years of experience in the current hospital, total years of experience as a nurse, and monthly gross salary (SAR) was examined through the Pearson’s product moment correlation.

A standard multiple linear regression analysis was performed to examine the effects of the independent variables – job satisfaction and QoL among staff nurses – on their intention to leave (dependent variable). The R2 and adjusted R2 were also reported to explain the variance of the predictor variables on the dependent variable. Confidence intervals (CI) of 95% were reported, and P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

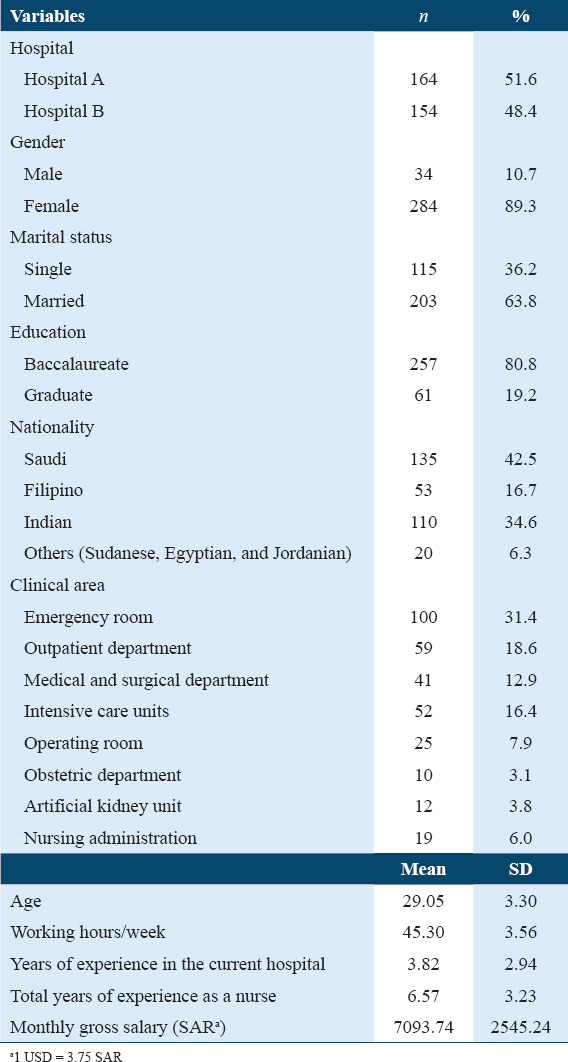

The demographic and work-related characteristics of the respondents are summarized in Table 1. Based on the results, 51.6% of the respondents worked in Hospital A and 48.4% worked in Hospital B. The mean age of the study participants was 29.05 years old (SD = 3.30). The majority of the respondents were female (89.3%), married (63.8%), and baccalaureate nursing degree graduates (80.8%). The largest proportion of the respondents was Saudis (42.5%). In terms of work-related characteristics, the respondents were evenly distributed among the different working areas in the hospitals.

Table 1.

Demographic and work-related characteristics of the respondents (n=318)

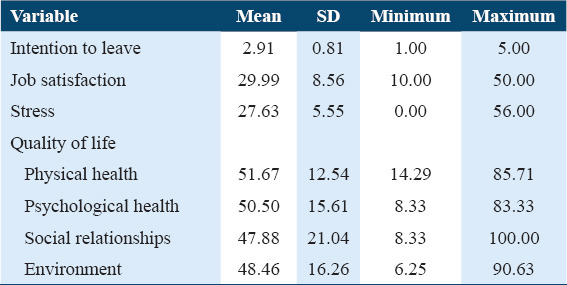

The results of the descriptive analyses of the study variables are shown in Table 2. The mean GJSS score of the respondents was 29.99 (SD = 8.56, range = 10.00–50.00), which indicates a moderate level of job satisfaction. Moreover, the participants reported a moderate level of stress, as shown by the mean PSS score of 27.63 (SD = 5.55, range = 0.00–56.00), which fell within the midpoint. The mean scores of the respondents in the physical health, psychological health, social relationships, and environment dimensions were 51.67 (SD = 12.54, range = 14.29–85.71), 50.50 (SD = 15.61, range = 8.33–83.33), 47.88 (SD = 21.04, range = 8.33–100.00), and 48.46 (SD = 16.26, range = 6.25–90.63), respectively.

Table 2.

Results of the descriptive statistics of the study variables (n=318)

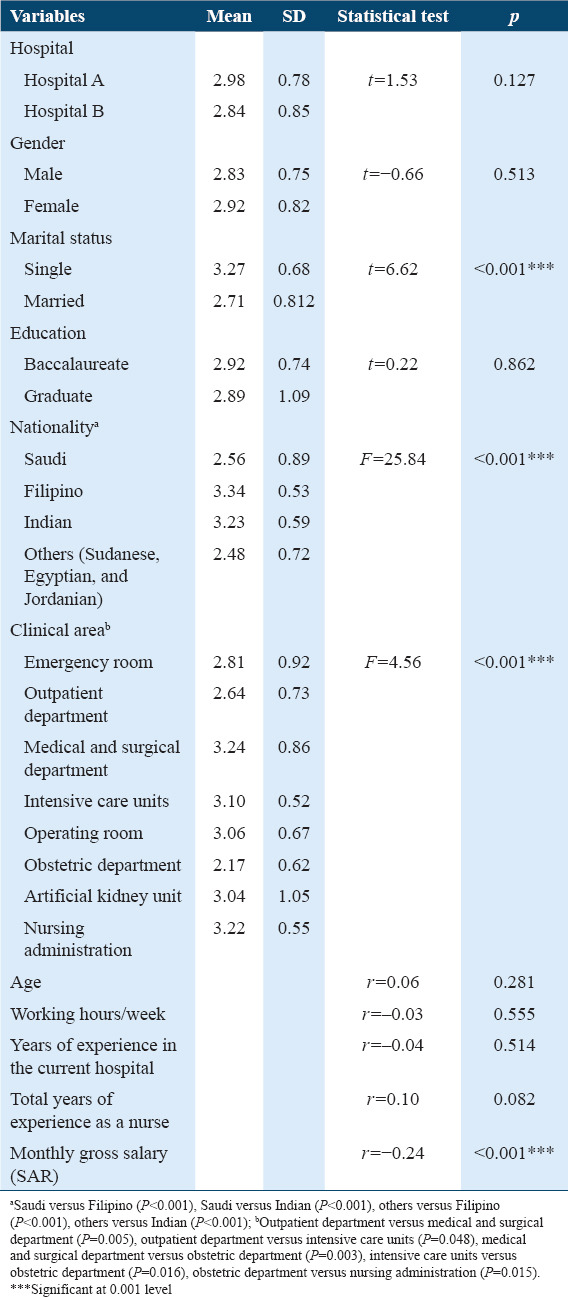

The mean TIS-6 score of the nurses was 2.91 (SD = 0.81, range = 1.00–5.00), indicating a moderate intention to leave. As shown in Table 3, nurses who were single (mean = 3.27, SD = 0.68) had a higher intention to leave their current workplace when compared to nurses who were married (mean = 2.71, SD = 0.812, t = 6.62, P < 0.001). Filipino nurses (mean = 3.34, SD = 0.53) had higher intention to leave levels when compared to Saudi nurses (mean = 2.56, SD = 0.89, P < 0.001) and other nationalities (Sudanese, Egyptian, and Jordanian; mean = 2.48, SD = 0.72, P < 0.001). Similarly, Indian nurses (mean = 3.23, SD = 0.59) reported higher intention to leave levels than Saudi nurses (P < 0.001) and other nationalities (P < 0.001). Moreover, significant differences were also revealed in the intentions to leave among nurses working in different clinical areas (F = 4.56, P < 0.001). Nurses working in the outpatient and obstetrics departments had lower intentions to leave than those in the medical and surgical departments and intensive care units. In addition, obstetric nurses had lower intentions to leave than those working in administration. A negative correlation was also revealed between a nurse’s monthly gross salary and his or her intention to resign (r = 0.24, P < 0.001).

Table 3.

Association between demographic and work-related characteristics and intention to leave to current job (n=318)

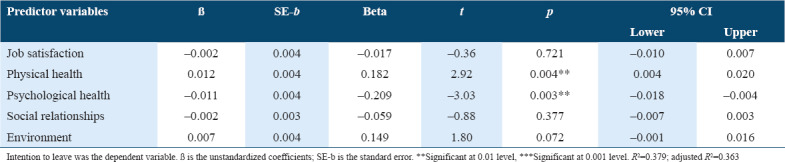

The nurses’ perceived job satisfaction and QoL scores were entered into a multiple regression analysis to predict the nurses’ intention to leave. Four variables were significant predictors, which accounted for 25.0% of the variance in the nurses’ perceptions (R2 = 0.379, adjusted R2 = 0.250). As shown in Table 4, emotional exhaustion, personal accomplishments, physical health, and psychological health were identified as significant predictors of the intention to leave. Moreover, a better physical health score positively impacted the intention to leave of the nurses (β = 0.012, P = 0.004, 95% CI = 0.004–0.020). Contrarily, a better psychological health score predicted a lower intention to leave (β = –0.011, P = 0.003, 95% CI = –0.018––0.004).

Table 4.

Predictors of intention to leave to current job (n=318)

Discussion

The results of the study revealed that the nurses reported a moderate level of job satisfaction, which is in agreement with another previous study on nurses in two different public secondary hospitals in Saudi Arabia.[8] A comparison of our findings with those of an integrative review on nurses in Saudi Arabia also confirmed that they experience moderate job satisfaction levels,[18] which are consistently associated with organizational turnover and the intent to leave their current jobs.[29] Thus, a nurse’s intent to leave his or her current position may be associated with job satisfaction. Another study reported that nurses have a higher resignation rate when they are less satisfied in their work.[8] Therefore, the association between job satisfaction and the intention to leave the current job warrants further exploration.

The result that nurses in Saudi Arabia experience moderate levels of stress is parallel to the findings of a study of 143 Brazilian nurses in one public hospital: More than half of the respondents (55.25%) also presented moderate stress.[30] Furthermore, a systematic literature review investigating the nursing shortage in Saudi Arabia revealed that stress among nurses was the result of excessive working hours and a low nursing staff:patient ratio.[31] This increases the probability that nurses are prone to errors and work fatigue, which can affect the quality of care provided to patients. An Iranian study also showed a medium stress range from 20% to 53% (n = 189) among nursing staff, although the causes of stress were not measured.[8] Other previous studies used a different tool in assessing stress levels, which may yield discrepancies in the results.[8,30] In addition, the present work focused only on measuring the stress levels and did not assess the association with the intention to leave the current job. Therefore, further research using a widely used, validated tool should be conducted to determine the causes of nurses’ stress that might affect their intention to leave their current jobs.

This study revealed that nurses perceived a poor QoL. Of the four QoL components, physical and psychological health significantly predicted the nurses’ intention to leave their current jobs. QoL provides nurses the motivation to perform well; a poor QoL may cause them to become unproductive and decrease the delivery of care.[32] Thus, this phenomenon may motivate them to leave their jobs. These results are consistent with an earlier study conducted on nursing staff in one public and one private hospital in the Philippines.[32] On the other hand, nurses with a better QoL show a higher sense of achievement, lower turnover, and a lower intention to leave.[33] Therefore, developing interventions to enhance well-being and work engagement and promote workforce retention are recommended. For example, establishing intervention programs (e.g., collaborative team efforts) and proposing pathways on how to increase employee well-being may improve the nurses’ QoL.

In terms of demographic and work-related factors, single nurses had a higher intention to leave their current workplace compared with married nurses. This phenomenon may imply that single nurses are free to change their jobs if they are dissatisfied without asking for approval from family members. Our work confirms other studies that found that single nurses reportedly experienced lower work engagement compared with married nurses.[21] In addition, the work demands for single nurses are higher because of the expectation that they have more time to work overtime than married ones, who have a family.[1] This might further increase single nurses’ workload, which could determine them to leave the nursing profession. In contrast, one study conducted in the United States negated these findings and showed that married women had high turnover rates.[34] The same study indicated that the connection between work and family responsibilities enhanced married nurses’ maturity in decision-making and work engagement.[34] Nevertheless, these contrasting results compelled us to assess how marital status affects deciding to leave an organization.

In the present study, Filipino and Indian nurses showed higher intention to leave levels compared with other nationalities. This is noteworthy as, according to a previous study, expatriate nurses in Saudi Arabia recruited from Arab countries were more likely to stay, whereas expatriate nurses from non-Arab Asian countries were more likely to leave.[18] In addition, the majority of the health-care personnel in Saudi Arabia consists of expatriates,[8] who have been reported to experience difficulty adjusting to Saudi culture, this being a reason why they tend to leave the workforce. It is most likely that cultural differences impact Filipino and Indian nurses’ values, beliefs, and behaviors in the workplace, and they might struggle to adjust to working in a different culture, leading to the intent to resign. Therefore, conducting training sessions and seminars related to cultural competence, which may provide expatriate nurses with a sense of satisfaction and fulfillment, could reduce their reasons to leave their jobs. In addition, new recruitment strategies, especially for Filipino and Indian nurses, need to be designed to retain them in the long term.

Nurses from the medical and surgical departments had a higher probability of resigning than those from other clinical departments. This finding is congruent with the results of an earlier study that found that nurses from the medical and surgical departments were particularly susceptible to stress (e.g., from pre-admission care, patient ratio, elective surgery care, post-surgery care and monitoring, and dealing regularly with life-and-death situations) compared to other clinical areas.[5] McCarthy et al.[19] suggested that uncooperative coworkers in the medical and surgical departments also contribute to high stress levels. Therefore, the nursing management should address this issue and treat it as a high priority.

Turning now to the monthly gross salary of nurses, our findings revealed that it is considerably related to their intention to leave. This result corroborates previous studies that found that high salaries were associated with nurse retention, whereas low compensation induced a strong intent to leave.[9] These findings were also supported by an integrative review assessing the previous literature on nursing turnover in the Saudi Arabian context, which revealed that the monthly gross salary was a determinant of the turnover and intention to leave of nurses.[18] Employment laws that address matters such as recruitment, employment, training and qualification requirements, employment contracts, and working conditions are implemented in Saudi Arabia, although various health-care settings may still implement different compensation schemes.[35] It is most certain that expatriate nurses may look for opportunities in other developed countries for high compensation and good working conditions. Therefore, hospital administrations should establish policies comparable with other developed countries, which might provide great incentives for the retention of the most qualified health workers. The relationship between the standard salary scheme and the nurses’ intention to leave should be further investigated to appropriately adjust the standard compensation.

The present work has a few limitations that should be considered. First, this study was conducted in a specific region, focused on two hospitals, and conveniently selected samples, which may have led to the underrepresentation of certain population segments. Second, the study used a cross-sectional design, which did not allow the researchers to identify other factors, such as professional growth (promotion), the type of hospital (public or private), leadership relations, and interpersonal conflict that might also cause nurses to leave their current jobs. Therefore, future studies using mixed methods or qualitative designs are recommended to gain a comprehensive understanding of the issues and problems causing nurses’ intention to leave.

Third, the intention to leave tool has limited specificity; that is, although it may be valid and reliable, it does not indicate the strength of the intention to leave.[26] Fourth, all the nurses in the obstetrics department were female; therefore, the finding that obstetric nurses have lower intentions to leave than those in other departments cannot be generalized.

Nevertheless, one of the strengths of this study is investigating the nurses’ unique perspective on their intent to resign in a thoughtful and considerate manner using tools with good psychometric properties. The present findings contribute to the limited literature on the factors that influence nurses’ intent to leave their current jobs in Saudi Arabia.

Conclusion

This study highlighted the factors that affect the intent to leave of nurses who work in Saudi Arabia. Nurses who are single, Filipino, or Indian, who work in the medical and surgical department, and have a low gross monthly income show a high intent to leave. The predictors of nurses’ intention to leave their current workplaces are QoL dimensions, such as physical and psychological health. Finally, our results provide a theoretical underpinning that expands on the previous knowledge and literature on the factors that affect nurses’ intent to leave their jobs.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank Deanship of Scientific of Research at Majmaah University R-1441-112 for supporting this work.

References

- 1.Almazan J, Albougami A, Alamri M. Exploring nurses'work-related stress in an acute care hospital in KSA. J Taibah Univ Med Sci. 2013;14:376–82. doi: 10.1016/j.jtumed.2019.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zaheer S, Ginsburg L, Wong HJ, Thomson K, Bain L, Wulffhart Z. Turnover intention of hospital staff in Ontario, Canada:Exploring the role of frontline supervisors, teamwork, and mindful organizing. Hum Resour Health. 2019;17:66. doi: 10.1186/s12960-019-0404-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.El-Jardali F, Alameddine M, Jamal D, Dimassi H, Dumit N, McEwen M, et al. A national study on nurses'retention in healthcare facilities in underserved areas in Lebanon. Hum Resour Health. 2013;11:49. doi: 10.1186/1478-4491-11-49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heinen M, Van Achterberg T, Schwendimann R, Zander B, Matthews A, Kozka M, et al. Nurses'intention to leave their profession:A cross sectional observational study in 10 European countries. Int J Nurs Stud. 2013;50:174–84. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2012.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alharbi J, Wilson R, Woods C, Usher K. The factors influencing burnout and job satisfaction among critical care nurses:A study of Saudi critical care nurse. J Nurs Manage. 2016;24:708–17. doi: 10.1111/jonm.12386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alshehry A, Alquwez N, Almazan J, Namis I, Moreno-Lacalle R, Cruz J. Workplace incivility and its influence on professional quality of life among nurses from multicultural background:A cross-sectional study. J Clin Nurs. 2019;28:2553–64. doi: 10.1111/jocn.14840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Al-Dossary R, Vail J, Macfarlane F. Job satisfaction of nurses in a Saudi Arabian university teaching hospital:A cross-sectional study. Int Nurs Rev. 2012;59:424–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1466-7657.2012.00978.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Najimi A, Goudarzi A, Sharifirad G. Causes of job stress in nurses:A cross-sectional study. Iran J Nurs Midwifery Res. 2012;17:301–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Perry L, Xu X, Duffield C, Gallagher R, Nicholls R, Sibbritt D. Health, workforce characteristics, quality of life and intention to leave:The “fit for the future“survey of Australian nurses and midwives. J Adv Nurs. 2017;73:2745–56. doi: 10.1111/jan.13347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mohammadi A, Sarhanggi F, Ebadi A, Daneshmandi M, Reiisifar A, Amiri F. Relationship between psychological problems and quality of work life of intensive care units nurses. Iran J Crit Care Nurs. 2011;4:135–40. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ibrahim N, Alzahrani N, Batwie A, Abushal R, Almogati G, Sattam M, et al. Quality of life, job satisfaction and their related factors among nurses working in king Abdulaziz university hospital, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. Contemp Nurse. 2016;52:486–98. doi: 10.1080/10376178.2016.1224123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.AlYami M, Watson R. An overview of nursing in Saudi Arabia. J Health Spec. 2014;2:10. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alonazi N, Omar M. Factors affecting the retention of nurses A survival analysis. Saudi Med J. 2013;34:288–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alharbi MF. An analysis of the Saudi health-care system's readiness to change in the context of the Saudi national health-care plan in vision 2030. Int J Health Sci. 2018;12:83–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Altakroni H, Mahmud I, Elmossad Y, Al-Akhfash A, Al-Hindi A, Joshva K. Healthcare productivity, and its sociodemographic determinants, of Saudi female nurses:A cross-sectional survey, Al-Qassim, Saudi Arabia 2017. Int J Health Sci. 2019;13:19–25. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Saquib J, Taleb M, Meimar R, Alhomaidan H, Al-Mohaimeed A, AlMazrou A, et al. Job insecurity, fear of litigation, and mental health among expatriate nurses. Arch Environ Occup Health. 2019;21:1–8. doi: 10.1080/19338244.2019.1592093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Al-Dossary R. The Saudi Arabian 2030 vision and the nursing profession:The way forward. Int Nurs Rev. 2018;65:484–90. doi: 10.1111/inr.12458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Falatah R, Salem OA. Nurse turnover in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia:An integrative review. J Nurs Manage. 2018;26:630–8. doi: 10.1111/jonm.12603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McCarthy V, Power S, Greiner BA. Perceived occupational stress in nurses working in Ireland. Occup Med. 2010;60:604–10. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqq148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Macdonald S, Maclntyre P. The generic job satisfaction scale:Scale development and its correlates. Employee Assist Q. 1997;13:1–16. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jaradat Y, Nielsen M, Kristensen P, Bast-Pettersen R. Shift work, mental distress and job satisfaction among Palestinian nurses. Occup Med. 2017:71–4. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqw128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.World Health Organization. WHOQOL-BREF Introduction, Administration, Scoring and Generic Version of the Assessment. 1996. [[Last accessed on 2019 Nov 16]]. Available from: https://www.who.int/mental_health/media/en/76.pd .

- 23.Leung K, Wong W, Tay M. Development and validation of the interview version of the Hong Kong Chinese WHOQOL-BREF. Qual Life Res. 2005;14:1413–9. doi: 10.1007/s11136-004-4772-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Min S, Kim K, Lee C. Development of the Korean versions of WHO quality of life scale and WHOQOL-BREF. Qual Life Res. 2002;11:593–600. doi: 10.1023/a:1016351406336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ohaeri J, Awadalla A. The reliability and validity of the short version of the WHO quality of life instrument in an Arab general population. Ann Saudi Med. 2009;29:98–104. doi: 10.4103/0256-4947.51790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bothma C, Roodt G. The validation of the turnover intention scale. SA J Hum Resour Manage. 2013;11:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav. 1983;24:385–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chiu Y, Lu F, Lin J, Nien C, Hsu Y, Liu H. Psychometric properties of the perceived stress scale (PSS):Measurement invariance between athletes and non-athletes and construct validity. Peer J. 2016;4:2–20. doi: 10.7717/peerj.2790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Naburi H, Mujinja P, Kilewo C, Orsini N, Barnighausen T, Manji K, et al. Job satisfaction and turnover intentions among health care staff providing services for prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Hum Resour Health. 2017;15:1–12. doi: 10.1186/s12960-017-0235-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guido L, Linch G, Pitthan L, Umann J. Stress, coping and health conditions of hospital nurses. Rev Esc Enferm USP. 2011;45:1427–31. doi: 10.1590/s0080-62342011000600022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Aboshaiqah A. Strategies to address the nursing shortage in Saudi Arabia. Int Nurs Rev. 2016;63:499–506. doi: 10.1111/inr.12271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cruz J, Cabrera D, Hufana O, Alquwez N, Almazan J. Optimism, proactive coping and quality of life among nurses:A cross-sectional study. J Clin Nurs. 2018;27:2098–108. doi: 10.1111/jocn.14363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Almogati G, Sattam M, Hussin B. Quality of life, job satisfaction and their related factors among nurses working in King Abdulaziz university hospital, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. Contemp Nurse. 2016;52:486–98. doi: 10.1080/10376178.2016.1224123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mazurenko O, Gupte G, Shan G. Analyzing U.S. nurse turnover:Are nurses leaving their jobs or the profession itself? J Hosp Adm. 2015;4:48–56. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Understanding Employment Law in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. 2016. [[Last accessed on 2016 Nov 14]]. Available from: https://www.shearman.com/media/Files/NewsInsights/Publications/2016/11/Understanding-Employment-Law-in-the-Kingdom-of-Saudi-Arabia-IA-11142016.pdf .