Abstract

Naturally occurring mutations in two separate genes, PKD1 and PKD2, are responsible for the vast majority of all cases of autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD), one of the most common genetic diseases affecting 1 in 1000 Americans. The hallmark of ADPKD is the development of epithelial cysts in the kidney, liver, and pancreas. PKD1 encodes a large plasma membrane protein (PKD1, PC1, or Polycystin-1) with a long extracellular domain and has been speculated to function as an atypical G protein coupled receptor. PKD2 encodes an ion channel of the Transient Receptor Potential superfamily (TRPP2, PKD2, PC2, or Polycystin2). Despite the identification of these genes more than 20 years ago, the molecular function of their encoded proteins and the mechanism(s) by which mutations in PKD1 and PKD2 cause ADPKD remain elusive. Genetic, biochemical, and functional evidence suggests they form a multiprotein complex present in multiple locations in the cell, including the plasma membrane, endoplasmic reticulum, and the primary cilium. Over the years, numerous interacting proteins have been identified using directed and unbiased approaches, and shown to modulate function, cellular localization, and protein stability and turnover of Polycystins. Delineation of the molecular composition of the Polycystin complex can have a significant impact on understanding their cellular function in health and disease states and on the identification of more specific and effective therapeutic targets.

Keywords: Polycystins, TRP channels, Ca2+ signaling, protein-protein interactions, Wnt

1. Introduction

Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD) is the most common genetically inherited disorder to result in chronic kidney disease [1] with a prevalence of 1 in 400–1,000 and is the fourth leading cause of end-stage renal disease [2]. ADPKD is characterized by the development of fluid filled cysts that dramatically enlarge the kidneys and severely compromise the functional integrity of the parenchyma [3]. Additionally, extra-renal abnormalities associated with the disease can include cystic involvement of different organs such as the pancreas, intracranial aneurysms, cardiac involvement and valvular heat diseases [4]. Disease pathogenesis most commonly results from mutations in two genes, PKD1 (~85% of cases) [5] or PKD2 (~15% of cases) [6], that encode PKD1 and TRPP2, respectively. Mutations in additional genes such as GANAB and DNAJB11 have recently been identified [7, 8].

PKD1 (Polycystin-1; PC1) is a large, integral membrane protein of 4303 amino acids (aa) with 11 membrane-spanning segments, an extensive extracellular N-terminal fragment and a short intracellular C-terminal tail [9]. Whereas the function of PKD1 has remained relatively elusive, TRPP2 (PKD2; Polycystin-2; PC2) has been shown to function as a non-selective Ca2+permeable cation channel and is a member of the transient receptor potential (TRP) ion channel family [10]. TRPP2 is comprised of 968 aa and spans the membrane six times with both N- and C-terminal domains facing the cytoplasm [6].

PKD1 and TRPP2 have been reported to associate with a myriad of protein families in a variety of cell types, tissues and cellular locations. These interactions have been described to serve a number of functions including trafficking, regulation, signaling, degradation, and recruiting additional interactors to form large multiprotein complexes. The objective of this review is to explore the interacting partners of PKD1 and TRPP2 to provide an angle for explaining the multifunctionality and complex regulation of these proteins. Additionally, the implications these interactions may have in ADPKD pathogenesis will be discussed.

2. Topology of PKD1 and TRPP2

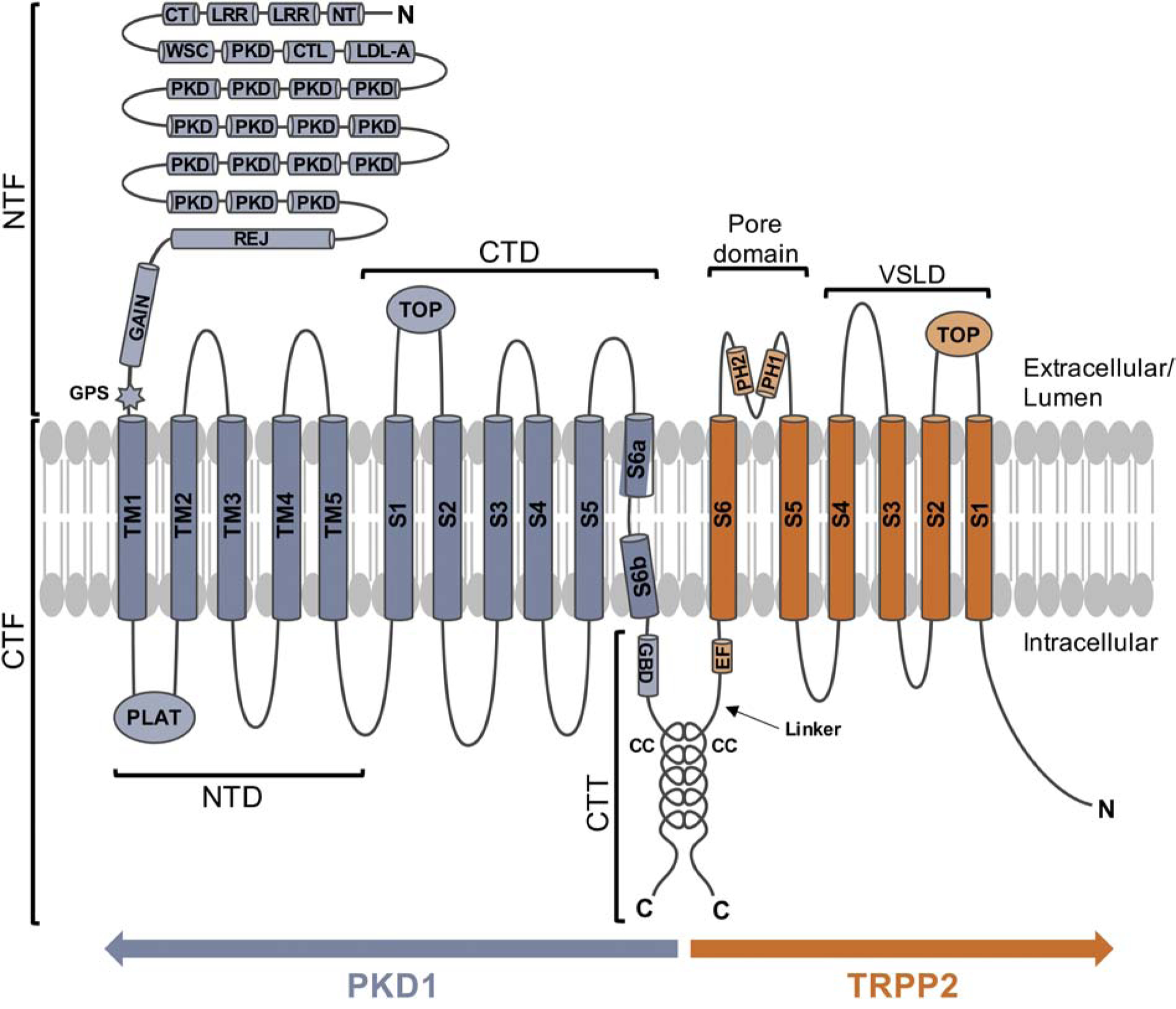

The extensive extracellular N-terminal fragment (NTF) of PKD1 is made up of 3073 aa and is comprised of a series of adhesive and ligand binding domains. These include two leucine-rich repeats (LRR) flanked by N-terminal (NT) and C-terminal (CT) cysteine-rich domains [11], a cell wall integrity and stress component (WSC) domain [12], a C-type lectin (CTL) domain [11], a low-density lipoprotein-A (LDL-A) domain [11], 16 Ig-like PKD repeats [11, 13], and an REJ module homologous to the sea urchin sperm receptor for egg jelly [14]. This extended region also contains a G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) proteolytic site (GPS) near the first transmembrane segment that undergoes cleavage during normal processing and trafficking and remains non-covalently associated at the cell surface (Fig. 1) [12, 15]. The GPS is part of a larger domain, the GPCR autoproteolysis-inducing (GAIN) domain, both of which are well-conserved features of adhesion GPCRs [16]. The 11 transmembrane domains and intracellular C-terminal tail (CTT) together comprise the C-terminal fragment (CTF) of PKD1. A five-transmembrane helix (TM1-TM5) bundle (NTD; N-terminal domain) follows the GPS site, and contains an intracellular β-barrel PLAT (polycystin-1, lipoxygenase, and alpha toxin) domain between TM1 and TM2 [17, 18]. PLAT domains are involved in protein-protein and protein-lipid binding [12, 17–19]. The final six transmembrane segments (S1–S6) make up the C-terminal domain (CTD) and include an extracellular TOP/polycystin domain between S1 and S2 that is frequently targeted for mutation in ADPKD [17]. The short C-terminal tail of PKD1 (189 aa) contains additional functional motifs, including a 74 aa G protein binding domain (GBD) [20] followed by an α-helical coiled-coil domain (aa 4214–4248) [21].

Figure 1. Topology of PKD1 and TRPP2.

PKD1 is shown in blue and TRPP2 is shown in orange. Abbreviations: N, N-terminus; C, C-terminus; NTF, N-terminal fragment; CTF, C-terminal fragment; NTD, N-terminal domain; CTD, C-terminal domain; CTT, C-terminal tail; LRR, leucine-rich repeat; NT, N-terminal cysteine-rich domain; CT, C-terminal cysteine-rich domain; WSC, cell wall integrity and stress component domain; CTL, C-type lectin domain; LDLA, low-density lipoprotein-A domain; PKD, Ig-like PKD repeat; REJ, REJ module homologous to the sea urchin sperm receptor for egg jelly; GAIN, GPCR autoproteolysis-inducing domain; GPS, GPCR proteolytic site; PLAT, polycystin-1, lipoxygenase, and alpha toxin domain; TOP, TOP/polycystin domain; GBD, G protein binding domain; CC, coiled-coil domain; EF, EF-hand domain; PH1, pore helix 1; PH2, pore helix 2.

As a result of its size, the characterization of PKD1 has proven exceedingly challenging. Though structural information has been provided for the transmembrane regions, PLAT and TOP domains, and the C-terminal tail, little is known regarding the extracellular N-terminal fragment. Several domain functions within this region have been characterized biochemically yet structural details are sparse. Knowledge of the structural organization of PKD1 in its entirety is crucial to understanding the multifunctionality of this protein. To date, only the structure for the first PKD repeat (aa 275–353) is in the protein database [22]. This structure, determined using NMR, revealed a β-sandwich topology. The domain is built from two β-sheets, one of three strands and one of four strands, which pack together with a well-defined hydrophobic core. Using combined bioinformatics, computational and biochemical data, another study modeled the three-dimension structure of the C-type lectin domain (aa 405–534) [23]. This domain, in complex with galactose and a Ca2+ ion, is composed of eight β strands, three α helices, and three disulfide bridges. The carbohydrate binding site was found to be located on the surface of the loop region and consists of a primary binding site along with several less specific secondary subsites. Insight has also been provided for the structures of the REJ domain and PKD repeat module through studies using atomic force microscopy to image PKD1 [24]. This work showed that the REJ domain protrudes into the extracellular space as a globular domain and acts as an anchor for the string-like region of tandem PKD repeats. Together, the PKD repeats were shown to assemble to form an easily deformable linker that positions the globular N-terminus about 35 nm from the membrane. Undoubtedly, further investigations are needed to fully elucidate the three-dimensional structure of the PKD1 N-terminal fragment. These studies will likely yield valuable insights into function and provide a basis for understanding the effects of mutations in the PKD1 gene.

In contrast to PKD1, structural information for TRPP2 has accumulated and provided detailed insight on homomeric assembly and activation. Shen et al. [25] reported a cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) structure of a truncated human TRPP2 (aa 198–703) reconstituted in lipid nanodiscs at 3.0-Å resolution. Grieben et al. [26] also reported a structure for the human construct (aa 185–723), solved at 4.2-Å resolution by cryo-EM in combination with X-ray crystallography data. Both reports reveal a closed conformation in which TRPP2 adopts a tetrameric architecture and each subunit consists of two distinct domains [25, 26]. The voltage sensor-like domain (VSLD) consists of helices S1–S4. The VSLD forms a classic voltage-gated ion channel (VGIC) four-helix bundle but lacks four of the six gating charges commonly found in VGICs. The pore domain includes the S5 and S6 helices and an intervening reentrant pore loop. The pore loop consists of two short pore helices (PH1 and PH2) separated by a selectivity filter [26]. The VSLD and pore domain are connected by a short, intracellular S4–S5 linker (Fig. 1) [25].

The ion permeation pathway consists of two gates, one at the selectivity filter region (641–643) and a lower gate at the S6 helix bundle crossing above the inner leaflet of the lipid bilayer [25, 26]. Like PKD1, TRPP2 has an extracellular TOP domain located between S1 and S2 [25, 26]. Detailed structural analysis reveals that this domain consists of three α-helices, a five-stranded anti-parallel β sheet, and two pore domain-facing elements: an S3–S4 loop extension and a β-hairpin [26]. The β-hairpin is part of a structure referred to as a three-leaf clover (TLC), which links adjacent TOP domains, the S3–S4 extension and the pore turret [26]. Four TOP domains assemble into a tightly packed tetrameric ring that resides above the VSLD and outer pore region and contributes to channel assembly through extensive homotypic interactions with an adjacent TOP domain of a neighboring subunit [25, 26].

In the structures described, TRPP2 is truncated at both cytoplasmic N- and C-termini, thus preventing structural determination for these regions. The intracellular N-terminal domain of TRPP2 is predicted to be intrinsically disordered and as a result, characterization of this region is limited. In contrast, the intracellular C-terminal region contains well-defined structural elements including an EF-hand domain (aa 717–790) connected by a flexible linker (aa 791–832) to a coiled-coil domain (aa 833–895) (Fig. 1) [27, 28]. The EF-hand domain contains one Ca2+binding site and is critical for Ca2+-dependent channel regulation [29–32]. The linker region between the EF-hand and coiled-coil includes multiple phosphorylation sites important for channel regulation [33, 34]. The coiled-coil domain has been shown to be involved in the formation of both homo- and hetero-oligomeric channel complexes [21, 35–38]. Interestingly, this domain forms a homotrimer, both in solution [39–41] and in crystals [39]. A crystal structure of the TRPP2 C-terminal fragment (aa 833–895) solved at 1.9-Å resolution shows that this fragment forms a continuous α helix and assembles into a trimer with two distinct regions [39]. The N-terminal region (aa 839–873) forms a classical coiled-coil and is tightly bundled through extensive hydrophobic interactions. In contrast, the C-terminal region of the α-helix (aa 874–895) spreads open and maintains a high level of conformational flexibility [28, 39].

PKD1 and TRPP2 are both predicted to be highly disordered and this property is implicated in many of the challenges faced in characterizing these proteins using data from structural studies. Analysis of this property using the Eukaryotic Linear Motif (ELM) resource, an online computational biology tool, shows that approximately 24% and 28% of PKD1 and TRPP2, respectively, are predicted to be disordered. Several of these regions overlap or entirely encompass known binding sites highlighting the importance of unstructured domains in these proteins. Moreover, structural disorder can provide important hints in understanding the multifunctionality and regulation of PKD1 and TRPP2. This may also provide an angle for explaining the difficulties in characterization, as disorder regions may not resolve well in structural studies and perhaps may only become ordered upon binding to another protein or through posttranslational modification. The significance of intrinsic disorder in PKD1/TRPP2 is further exemplified by the number of disease-associated missense mutations localized within these regions. Information provided from the ADPKD mutation database reveals that 169 different missense mutations in PKD1 and 16 in TRPP2 occur within predicted disordered regions. These mutations could affect anything from protein folding/trafficking to posttranslational modifications and protein-protein interactions. This underscores the unmitigated importance of PKD1/TRPP2 intrinsic disorder and shows that this phenomenon cannot be ignored.

3. PKD1 and TRPP2 interact to form a receptor-channel complex

Early studies showed that the coiled-coil domains of PKD1 and TRPP2 associate with each other in vitro [21, 35]. The coiled-coil domain of TRPP2 has since been shown to form a homotrimer that interacts with the coiled-coil of one PKD1 molecule to form a 3:1 complex [39]. Disruption of trimer formation abolished the PKD1/TRPP2 interaction, disrupted complex assembly, and diminished the surface expression of both proteins. Further studies using a computational approach revealed a distinct di-trimer configuration for the PKD1-TRPP2 coiled-coil interaction [28]. In this configuration, an upstream trimer is formed by three TRPP2 helices and a downstream trimer is formed by two TRPP2 helices and one PKD1 helix. Functionally, the PKD1-TRPP2 interaction has been shown to produce new Ca2+-permeable non-selective cation currents of which neither PKD1 nor TRPP2 alone could produce [42]. ADPKD-associated mutants that prevent complex formation were unable to produce current [42].

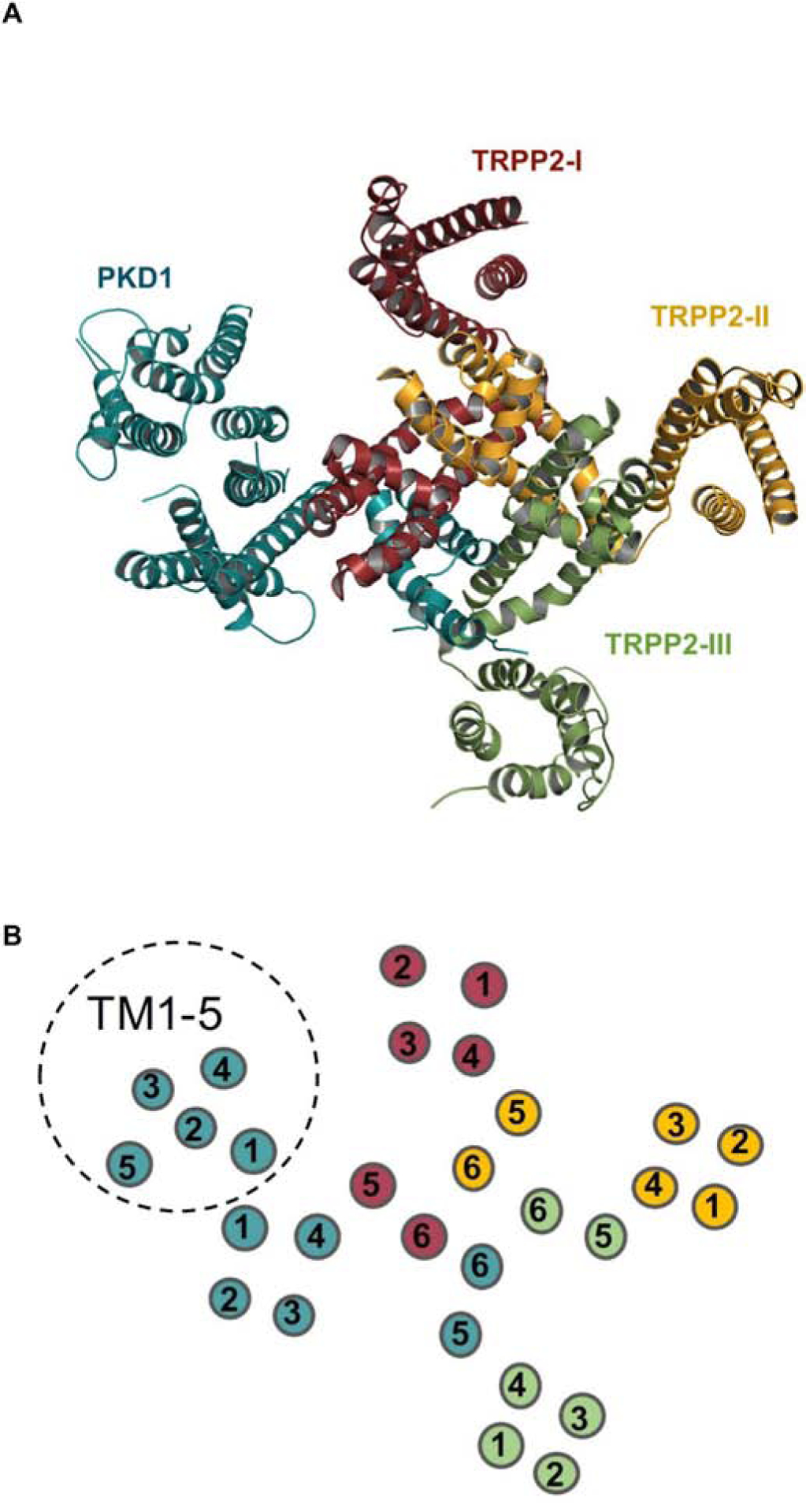

More recently, a structure for the PKD1/TRPP2 complex was resolved to 3.6-Å with single-particle cryo-EM [17]. This work was accomplished using truncated human PKD1 (aa 3049–4169) and TRPP2 (aa 185–723). The structure confirmed the 1:3 ratio of PKD1 and TRPP2, respectively, and provided further insight on complex assembly (Fig. 2). PKD1 contains a voltage-gated ion channel (VGIC) fold that interacts with TRPP2, revealing a domain-swapped TRP channel architecture. Like TRPP2, S1–S4 of PKD1 comprise the VSLD and an extracellular TOP domain is formed between S1 and S2. Notably, the TOP domain of PKD1 deviates ~15° from the expected symmetric position within the complex. The luminal loop and TLC, which mediate TOP domain interactions between TRPP2 subunits, are absent from PKD1 (sequence and structure) and invisible in the EM map, respectively. The invisibility of the TLC was proposed to likely result from the flexibility of this region. Two additional interfaces below the TOP domains occur within the complex: an electrostatic interaction between the PKD1 TOP domain and the S6-PH2 linker of TRPP2-I and a hydrophobic interface between S4 of PKD1 and S5 of TRPP2-I. The four-fold symmetry of the pore domain within the complex is broken as a result of a distinct conformation exhibited by the S6 segment of PKD1. The segment is bent in the middle, and the two halves, S6a and S6b, form an axial angle of 120°. S6a resembles PH1 of TRPP2, but the sequence likely corresponding to the SF and PH2 (between S6a and S5) is highly flexible and disordered and could not be analyzed. From S6b, three positively-charged residues (R4100, R4107, and H4111) protrude into the cavity and are stabilized by neighboring residues on S6 of TRPP2–1, indicative of a nonconductive receptor-channel state as this would likely impede cation permeability. Overall, while there is little doubt that PKD1 and TRPP2 can form a complex, it is currently unclear whether the formation of such complex is functional in terms of ion permeation. One possibility is that at the resting state, PKD1 prevents constitutive activation of TRPP2, whereas in the activated state, the PKD1-mediated block of TRPP2, is lifted.

Figure 2. PKD1 and TRPP2 assemble to form a 1:3 receptor-channel complex.

(A) Topdown view of the PKD1TRPP2 complex. The one PKD1 subunit is shown in teal and the three TRPP2 subunits are shown in ruby red, yellow-orange, and green, respectively. Complex modeling was done using PDB code 6A70 in PyMOL 2.3. TOP and PLAT domains have been removed from the structure to clearly demonstrate transmembrane architecture. (B) Schematic top-down view displaying the numbered arrangement of the transmembrane segments. Subunit colors correspond to those shown in (A). TM1-TM5 of PKD1 are indicated by a dashed circle.

3.1. WNT signaling

A study by Kim et al. identified secreted WNTs as activating ligands of the PKD1/TRPP2 complex [43]. WNTs were shown to bind a region of the NTF (CT and WSC domains) of PKD1 and induce whole cell currents and Ca2+ influx dependent on TRPP2. Pathogenic mutations that disrupted complex formation, compromised PKD1 surface expression, or reduced TRPP2 activity suppressed activation by WNTs. This study also showed that TRPP2 is required for WNT9B-induced directed cell migration, which is a Ca2+-dependent process often used as a proxy for convergent extension during kidney tubule elongation. Lastly, wnt9a, pkd1, and dishevelled 2 (dsh2) were shown to function in the same pathway to control Xenopus pronephric tubule formation. These findings suggest that PKD1 functions as a WNT receptor and that defects in this interaction may disrupt downstream processes implicated in ADPKD pathogenesis. Additional support for the involvement of the PKD1/TRPP2 complex in WNT signaling was obtained by the identification of PKD1 as a Dishevelled (DVL in vertebrates) binding partner. Since DVLs function as a hub for WNT signaling and dsh2 (Dishevelled2 in Xenopus) epistatically interacted with pkd1 in Xenopus pronephric development, it is logical to conclude that PKD1 and TRPP2 may function downstream of WNT signaling in this system. Whether WNT-induced activation of PKD1/TRPP2 results in ion permeation that mediates these in vivo effects is currently unknown. Nevertheless, the identification of secreted WNTs as the first activating ligands of the PKD1/TRPP2 complex may help address questions on the activation mechanisms of the PKD1/TRPP2 complex and the role of PKD1 in TRPP2-mediated channel activity.

4. PKD1-mediated G protein signaling

PKD1 has been proposed to act as an atypical GPCR, as it lacks the canonical seven transmembrane configuration yet is able to bind and activate heterotrimeric G proteins through a highly conserved GBD within the cytosolic C-terminal tail [20]. This initial study employed PKD1 fusion constructs to investigate G protein binding and found that purified Gαi/o and Gβγ subunits both interact with PKD1 but did not bind TRPP2. Another study using rat sympathetic neurons as a heterologous expression system confirmed this finding using full-length PKD1 and also showed that PKD1 activated Gαi/o but not Gαq subunits [44]. PKD1-activated Gαi/o subunits modulated the activity of Ca2+ and K+ channels via the release of Gβγ subunits. Co-expression with full-length TRPP2 abrogated the effects of PKD1, whereas a TRPP2-C-terminal truncation mutant had no effect. This suggests that TRPP2 may play a role in regulating PKD1-mediated G protein signaling. It remains unknown whether binding of an extracellular ligand or additional protein at the PKD1/TRPP2 coiled-coil domain region could serve to release TRPP2 inhibition and enable G protein activation.

Downstream of PKD1-G protein activation, c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK)/AP-1 activation is mediated by Gα and Gβγ subunits [45]. JNK and AP-1 activities were assayed in transiently transfected 293T cells in the presence of dominant-negative, G protein inhibiting constructs, and in the presence of co-transfected Gα subunits. PKD1-mediated AP-1 activity was found to be enhanced by co-transfected Gαi, Gαq, and Gα12/13 subunits. Gα12 has been shown to stimulate apoptosis in epithelial cells through JNK-mediated degradation of the anti-apoptotic protein, Bcl-2 [46]. This pathway was confirmed in Madin-Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cells in which PKD1 expression levels were found to modulate Gα12/JNK-stimulated apoptosis [47]. PKD1-overexpressing cells were resistant to thrombin/Gα12stimulated apoptosis, JNK activation, and Bcl-2 degradation, whereas PKD1-silenced cells showed enhanced thrombin-induced apoptosis, JNK activity, and Bcl-2 degradation. Thrombin-stimulated cells showed increased interaction of Gα12 and PKD1, and a PKD1 mutant lacking the GBD was uncoupled from PKD1-inhibited apoptosis. Mutational analysis of Gα12 and PKD1 was used to identify regions required for their interaction [48]. This identified three substitutions in Gα12 that displayed >90% impairment in binding to PKD1, and these Gα12 mutants were resistant to PKD1-mediated inhibition of Gα12-stimulated apoptosis in HEK293 cells overexpressing PKD1. Likewise, deletion of the Gα12interacting sequence from PKD1 abrogated inhibition of Gα12-stimulated apoptosis. Altogether, these data suggested that tethering of Gα12 to PKD1 protects thrombin- and perhaps, other GPCR-induced apoptosis.

The necessary role of Gα12 in renal cystogenesis has been examined in knockout mice for Pkd1 and the gene encoding Gα12 (Gna12) [49]. Gna12-knockout mice (Gna12−/−) showed no phenotypic abnormalities, whereas induced knockout of Pkd1 (Mx1Cre+;Pkd1f/f;Gna12+/+) in 1week-old mice resulted in multiple kidney cysts by 9 weeks. Double knockouts (Mx1Cre+;Pkd1f/f;Gna12−/−) showed no structural or functional abnormalities in the kidneys, and mice were able to survive over a year without kidney abnormalities. Some mice exhibited hepatic cysts, further indicating a kidney-specific effect mediated by Gα12 in cystogenesis. These results suggest Gα12 is required for cyst development induced by mutations in PKD1. The previously mentioned studies suggested mutations in PKD1 that abrogate binding to Gα12 may lead to increased levels of free Gα12 and thereby enhance apoptosis [47, 48]. In combination, the information presented here suggests that heightened levels of free Gα12 resulting from GBD mutations in PKD1 may drive apoptosis and this process may contribute to cystogenesis. However, the possibility that PKD1-free Gα12 may drive cystogenesis independently of apoptosis in vivo has not been evaluated.

G-protein signaling modulator 1 (GPSM1), an accessory protein which functions as a guanine nucleotide dissociation inhibitor, has been reported to modulate cyst progression in an orthologous mouse model of ADPKD [50]. To investigate the role of GPSM1 in renal epithelial cell cystogenesis, Gpsm1 null mice were crossed with a mouse model of ADPKD, Pkd1V/V is protected from proteolytic cleavage at the GPS and exhibits a somewhat less severe phenotype compared to the phenotype induced by deletion of the Pkd1 gene. Complete loss of Gpsm1 in the Pkd1V/V mouse model accelerated cyst progression and decreased renal function compared to cystic Pkd1V/V;Gpsm1+/+ and Pkd1V/V;Gpsm1+/− mice. Further, electrophysiological studies revealed that GPSM1 competes with Gβγ to bind Gαi/o-GDP subunits and the release of free Gβγ-dimers increases PKD1/TRPP2 ion channel activity. This study demonstrates an important role for GPSM1 and highlights a potential link between PKD1-mediated G protein signaling and PKD1/TRPP2 channel activity in controlling the dynamics of cyst progression.

Another accessory protein that may have implications in PKD1-mediated G protein signaling is RGS7. This short-lived regulator of G protein signaling (RGS) protein has been shown to bind the C-terminus of PKD1 [51]. RGS proteins bind and accelerate the intrinsic GTPase activity of Gα subunits, typically Gαi and Gαq subunits [51]. RGS7 is rapidly degraded by the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway, but upon interaction with the last 70 aa of the PKD1 C-terminal tail, RGS7 half-life is prolonged. This association may serve an important role in regulating G protein signaling mediated by PKD1. Of note, both RGS7 and PKD1 are highly expressed in the tubular structures of the developing kidney [51]. Further studies will be needed to elucidate the role of RGS7 in PKD1 function and in kidney development.

A single leucine deletion (L4132Δ or ΔL) in the GBD of PKD1 has been reported in ADPKD patients and was found to cause severe postnatal cystic disease in a kidney-specific knock-in mouse model [52]. This deletion was shown to significantly impair PKD1-stimulated, G protein (Gα12 and Gαq)-dependent signaling to AP-1 in transient transfection assays. Co-expression of PKD1ΔL and TRPP2 in transfected CHO cells revealed impaired TRPP2 channel activity in comparison to wild type PKD1/TRPP2 complexes. Together, these results indicate that L4132Δ prevents PKD1-mediated G protein activation and downstream signaling events that ultimately contribute to a severe cystic phenotype. Moreover, this work suggests that PKD1-mediated G protein signaling regulates PKD1/TRPP2 channel activity.

In support of this notion, PKD1-mediated G protein activation has been revealed to activate the canonical transient receptor potential 4 (TRPC4) channel [53]. Gαi3 was found to selectively bind the GBD of PKD1 and dissociate upon PKD1 cleavage, resulting in an increase in TRPC4 activity. In turn, this activation increased Ca2+-dependent activation of the transcription factor STAT1. Down-regulation of PKD1 and TRPC4 or knockdown of STAT1 reduced endothelial cell migration, and inhibition of PKD1-mediated TRPC4 activity increased endothelial cell permeability. These findings suggest that PKD1-mediated G protein signaling is important for endothelial cell migration/integrity and may help to develop a better understanding of the frequent association of aneurysms with ADPKD. Of note, this study revealed that the CTF of PKD1 is able to mediate G protein signaling, suggesting that removal of the NTF can render CTF signaling competent. This would be consistent with a function of PKD1 as an adhesion GPCR, where removal of the NTF can induce receptor activation.

A recent study using the pronephric kidney of Xenopus as a model system demonstrated that select Gα subunits (Gαs, Gαi1/2 and Gα12/14) bind the PKD1 C-terminal tail at affinities within range of those for other GPCRs [54]. Upon knockdown of these Gα subunits in Xenopus, a PKD phenotype was observed that was notably similar to the one for PKD1. Mechanistically, this phenotype was found to result from an increase in endogenous Gβγ signaling, which could be reversed through Gβγ inhibition or knockdown. Overall, there is strong evidence implicating G protein signaling directly associated with PKD1, which is supported by reports from several laboratories that various G protein subunits bind to the C-terminal tail of PKD1. However, a unifying theory of the exact mechanism(s) by which G protein signaling is integrated into PKD1 and/or TRPP2-mediated signaling and the role of G protein signaling in cyst formation and/or expansion is still outstanding.

5. PKD1 interactors at cell junctions

Epithelial cells are comprised of two major types of cytoskeletal anchoring junctions: cell-cell junctions localized on the lateral surfaces and cell-matrix junctions localized on the basal surface. Cell-cell junctions include the adherens junctions and desmosomes which link the actin filaments and intermediate filaments, respectively, of adjacent cells. Cell-matrix junctions link these filaments to the extracellular matrix (ECM) and include the actin-linked cell-matrix junctions and hemidesmosomes [55]. In the kidney, PKD1 is present in epithelial cells and has been shown to interact with a multitude of proteins involved in cell-cell and cell-matrix junction formation.

5.1. Adherens junction proteins

PKD1 has been shown to colocalize with the adhesion molecules E-cadherin and α-, β-, and γ-catenin [56]. Immunocytochemistry, sucrose density gradient sedimentation, co-IP analyses and in vitro binding assays showed that PKD1 forms complexes with E-cadherin and β- and γ-catenin in confluent normal human fetal collecting tubule (HFCT) epithelia when cell-cell interactions are predominant [57]. These studies were carried out using a PKD1 fusion protein containing the intracellular portion from S6 to the C-terminus (aa 4105–4303). β-catenin was found to associate with the C-terminal tail. Inhibition of tyrosine phosphorylation by tyrphostin or high Ca2+ treatment enhanced PKD1-E-cadherin interactions. Markoff et al. [58] demonstrated that the Ca2+ and phospholipid binding protein, annexin A5, interacts directly with the N-terminal LRR of PKD1. In MDCK cells, PKD1 was shown to accelerate the recruitment of E-cadherin to junctions and this recruitment was delayed in the presence of extracellular annexin A5 [58]. In ADPKD epithelial cells, the assembly and stabilization of E-cadherincontaining adherens junctions is disrupted [59]. This study suggests that PKD1 may function in the assembly and stabilization of adherens junctions, and mutations in PKD1 may lead to impairment of kidney epithelial cell-cell adhesion in ADPKD. This hypothesis is consistent with the observation that cell adhesion and proper tubule diameter is disrupted in cystic structures and loss of cell adhesion can trigger cell proliferation, a hallmark or polycystic kidney disease.

5.2. Desmosomal proteins

Within desmosome complexes, PKD1 has been shown to interact with different intermediate filament proteins, including vimentin, cytokeratins K8 and K18 and desmin [60]. These interactions occur at the intracellular C-terminal tail of PKD1 and are mediated by the coiled-coil motifs in both PKD1 and intermediate filament proteins. It has been proposed that PKD1 may utilize this association for structural, storage, or signaling functions [60]. In ADPKD cells, PKD1 and desmosomal proteins are depleted from the intercellular junction membrane, demonstrating that in the absence of functional PKD1, desmosomal junctions cannot be properly assembled [61]. Further evaluations revealed profound mispolarization of desmosomal components to both the apical and basolateral domains, decreased cytokeratin levels, abnormal expression of vimentin, and weakened cell-cell adhesion in primary ADPKD cells and tissue [62].

5.3. Extracellular matrix proteins

At cell-matrix junctions, various motifs within the extracellular N-terminal fragment of PKD1 have been shown to mediate interactions with ECM proteins. Collagens type I, II and IV have each been shown to bind the C-type lectin domain of PKD1 [63]. Notably, the expression of both types I and IV collagen are altered in ADPKD, and disruption of the interactions between collagen and PKD1 have been proposed to contribute to the disruption of epithelial cell polarity in ADPKD [64–66]. Using blot overlay assays, Malhas et al. [67] demonstrated an interaction between the LRR of PKD1 and collagen I, as well as fibronectin, laminin, and cyst fluid–derived laminin fragments. These studies assays were conducted using both the full-length PKD1 and a GST-fusion protein containing the LRRs and the LRR-flanking cysteine-rich domains of PKD1. No binding was detected for collagens II, III, or IV. Cyst fluid–derived laminin fragments were shown to have a stimulatory effect on cell proliferation in culture, and this effect was reversed by the addition of the LRR fusion protein. The association between the C-type lectin domain and/or LRR of PKD1 with ECM proteins could be important for cell-matrix stability/signaling, and disruption of these interactions may result in or enhance several characteristic features of ADPKD. Notably, the fusion construct used to demonstrate LRR-ECM interactions contains a region that overlaps with the WNT-binding domain. This could suggest that interactions between ECM components and PKD1 regulate the availability of other ligand-binding domains within the N-terminal fragment.

5.4. Focal adhesion proteins

Focal adhesions are formed upon cell-matrix attachment, which induces the formation of integrin clusters to recruit focal adhesion structure proteins [68]. In normal renal fetal ureteric bud-derived collecting tubule epithelia, PKD1 has been shown to associate with several focal adhesion proteins following attachment to type I collagen, the major ECM component in developing kidneys [57]. Co-sedimentation and co-IP analyses using the C-terminal tail of PKD1 revealed the formation of complexes containing the focal adhesion proteins pp125FAK, pp60src, p130Cas, and paxillin and the actin-binding proteins vinculin, talin and α-actinin. The composition of complexes was dependent on cell density and the duration of attachment to type I collagen. Inhibition of tyrosine phosphorylation by tyrphostin was shown to inhibit PKD1-FAK interactions. In conjunction with PKD1-ECM interactions, the associations presented here further signify a critical role mediated by PKD1 in cell-matrix signaling.

6. Phosphatase regulation of PKD1

RPTPσ, RPTPδ and RPTPγ are members of the classical receptor protein tyrosine phosphatase (RPTP) family and have been identified as regulatory, interacting partners of a multimeric PKD1 complex [69]. The first extracellular PKD domain of PKD1 interacts with the first extracellular Ig domain of RPTPσ, while the intracellular C-terminal tail of PKD1 interacts with the intracellular phosphatase domain of RPTPγ. The RPTPs colocalize with PKD1 in cilia and with the PKD1/E-cadherin complex at adhesion complexes in renal epithelia. In ADPKD cells, the interaction between PKD1 and RPTPγ is disrupted. These data suggest that RPTPs form multimeric complexes with PKD1 and regulate PKD1 function in multiple cellular locations, with possible implications in ADPKD.

Another study demonstrated that the serine/threonine phosphatase, protein phosphatase-1α (PP1α), interacts with and dephosphorylates PKD1 [70]. This study revealed a highly conserved protein PP1-interaction motif (RVxF) in the C-terminal tail of PKD1. Mutations within this motif, including an ADPKD-associated mutation, reduced PP1α-mediated dephosphorylation of PKD1. Authors suggested that PKD1 and PP1α may interact to form a holoenzyme complex and speculate that this complex may regulate aspects of PKD1-mediated signaling.

7. PKD1 and ubiquitin ligase interactions

The human homolog of Drosophila seven in absentia (Siah-1) is a RING domain protein that functions in E3 ubiquitin ligase complexes to promote the ubiquitin-dependent proteasome pathway [71]. Through two-hybrid screening using the PKD1 C-terminal tail (PKD1-CTT) as bait, Siah-1 was identified as a PKD1-binding protein [72]. Siah-1 binds the coiled-coil motif of PKD1 and induces the ubiquitination and degradation of the PKD1-CTT via the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway, suggesting Siah-1 may play a role in PKD1 turnover and function. It would interesting to know whether Siah-1 has similar effects on full-length PKD1 alone or in complex with TRPP2.

Jade-1 is a ubiquitin ligase for β-catenin [73] and has also been shown to bind the coiled-coil domain of PKD1 [74]. Full-length PKD1 was found to stabilize and inhibit Jade-1 ubiquitination, whereas the C-terminal tail or the naturally occurring C-terminal fragment of PKD1 were both found to promote Jade-1 ubiquitination and degradation [74]. ADPKD-associated PKD1 mutants failed to regulate Jade-1, indicating a link between disease and Jade-1 regulation by PKD1. This study additionally showed that Jade-1 ubiquitination was mediated by Siah-1, targeting Jade-1 for degradation. This may occur through differential control of Siah-1 by the cleaved versus full-length PKD1. The interplay between PKD1, Siah-1, and Jade-1 may serve to control β-catenin levels within the cell and thereby regulate canonical WNT signaling.

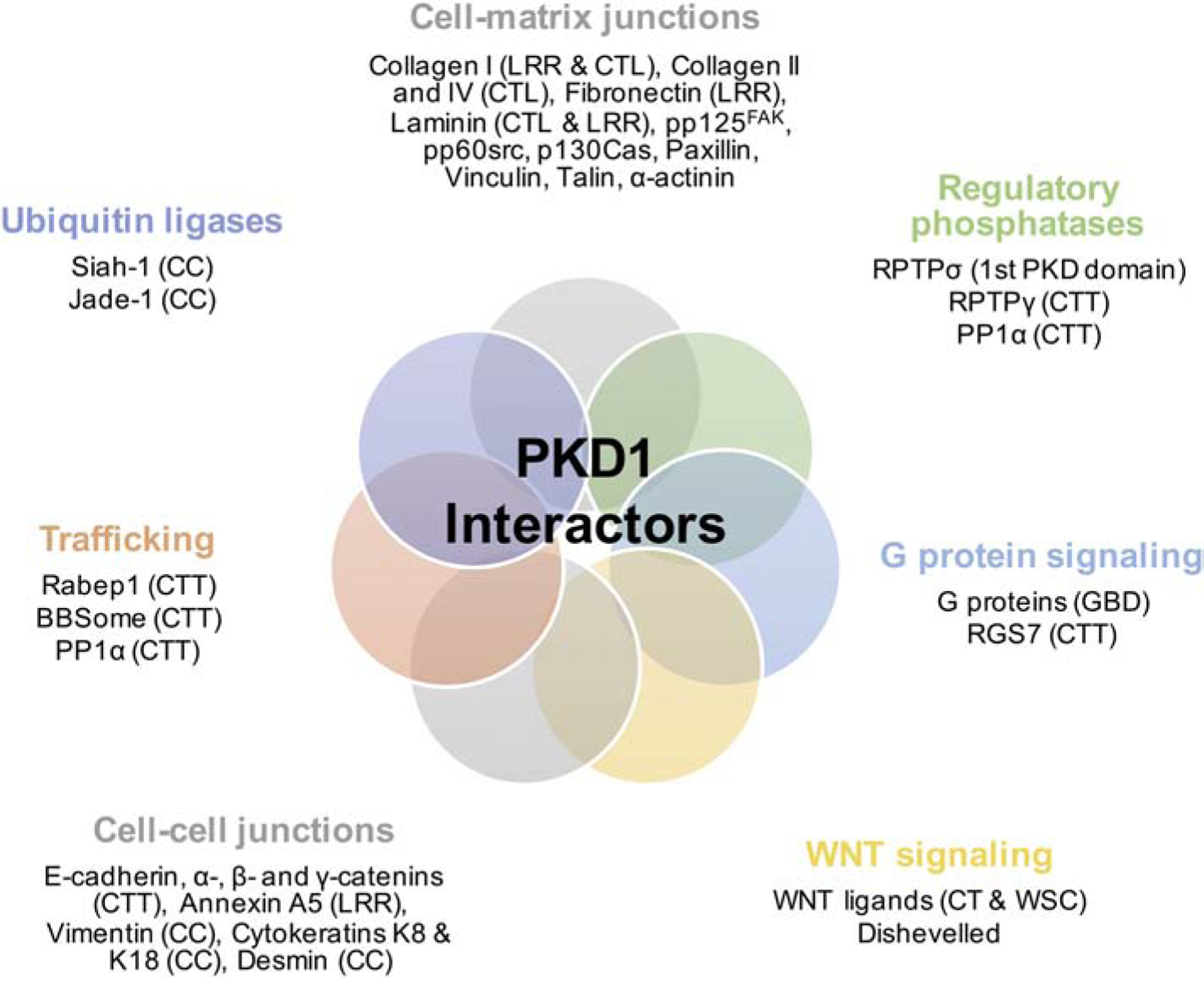

Overall, proteins of diverse functions have been shown to interact with PKD1 implicating PKD1 in cellular signaling and the regulation of the epithelial cytoskeleton (Fig. 3). These roles are well supported by its primary structure, as an atypical GPCR and/or adhesion GPCR, for example, and its well-established involvement in maintaining epithelial structure and integrity. However, it should be kept in mind that PKD1 is expressed in diverse cell types, such as fibroblasts, neuronal cell types, vascular smooth muscle cells, etc, and thus, currently unknown functions may emerge.

Figure 3. Diagrammatic representation of PKD1 interactors.

Known PKD1 domains involved in binding are shown in parentheses. Abbreviations: CTT, C-terminal tail; LRR, leucine-rich repeat; CT, C-terminal cysteine-rich domain; WSC, cell wall integrity and stress component domain; CTL, C-type lectin domain; GBD, G protein binding domain; CC, coiled-coil domain.

8. TRPP2 regulation by the actin cytoskeleton

Studies have shown that TRPP2 colocalizes with actin filaments and actin-binding proteins [75–80] both at the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and plasma membrane, and several interactions have been shown to modulate channel function [78, 79, 81]. An indirect association between TRPP2 and the actin microfilament has been shown through the interaction of TRPP2 and the actin-associated protein Hax-1 [75]. These studies revealed that loop 5 of PKD2 mediates interaction with Hax-1, and further demonstrated an association between Hax-1 and the F-actin-binding protein cortactin. TRPP2 and Hax-1 were found to colocalize primarily at the ER. Authors proposed that the interaction of TRPP2 and Hax-1 could occur at the ER or at the plasma membrane in complex with PKD1, and that in either case cortactin-binding to Hax-1 mediates association with the actin cytoskeleton [75]. Another study reported a direct association between TRPP2 and the actin microfilament upon identification of a specific interaction between the TRPP2 cytoplasmic C-terminal domain and tropomyosin-1, a component of the actin microfilament complex. This interaction was demonstrated both in vitro, as well as in vivo using native human embryonic kidney cells and human adult kidney [76].

Like tropomyosin-1, cardiac troponin-1, a regulatory component of the actin microfilament in cardiac muscle cells, has also been shown to interact with the C-terminal domain of TRPP2 [77]. This association was demonstrated in mouse fibroblast NIH 3T3 cells and Xenopus oocytes, and further verified in human adult heart tissue. Troponin I functions as an inhibitor of angiogenesis, and mutations that disrupt the TRPP2-troponin-1 interaction could account for the correlation between angiogenesis and ADPKD [82]. Another study by this group demonstrated that both the intracellular N- and C-terminal domains of TRPP2 associate with α-actinins which are actin-bundling proteins important for cell adhesion, proliferation and migration [78]. This association was confirmed in vitro, and an in vivo interaction was demonstrated in HEK293 cells, MDCK cells, rat kidney/heart tissues, and human syncytiotrophoblast (hST) apical membrane vesicles. This study also revealed that α-actinin stimulated TRPP2 channel activity in reconstituted lipid bilayers from hST vesicles. These findings suggest that disruption of the TRPP2-α-actinin association could be implicated in abnormal cellular processes observed in ADPKD and links the regulation of TRPP2 channel activity to actin cytoskeletal dynamics [78].

The physical and functional interaction between TRPP2 and the actin cross-linking proteins known as filamins, further supports this notion. The C-termini of filamin-A, B and C were shown to bind directly to both the N- and C-terminal domains of TRPP2, and both filamin-A and TRPP2 were found to reside in the same complex in renal epithelial cells [79]. In contrast to α-actinin, filamin-A was found to inhibit TRPP2 channel activity in a lipid bilayer reconstitution system, indicating a negative regulatory mechanism for TRPP2 channel function coupled to the actin cytoskeleton. Additional studies aimed to identify the effects of filamin on TRPP2 stability demonstrated that filamin-A is associated with higher TRPP2 cell surface expression and repressed TRPP2 degradation [80]. Filamin-A mediates the binding of TRPP2 with actin, thus forming a complex to stabilize TRPP2 on the plasma membrane. The interaction of filamin-A and TRPP2 was reported to be Ca2+-dependent, indicating that high intracellular Ca2+ levels may promote binding of filamin-A to inhibit TRPP2 channel activity [80]. Of note, the physical interaction of TRPP2 and filamin was also implicated in the function of TRPP2 as a regulator of stretch-activated ion channels [83].

9. TRPP2 regulation by microtubules

Evidence strongly implicates abnormalities in the microtubule-enriched primary cilia of renal epithelial cells in ADPKD cyst formation [84, 85]. A single, non-motile primary cilium protrudes from the apical surface of most renal tubular epithelial cells and responds to fluid flow by eliciting intracellular Ca2+ signals [86, 87]. TRPP2 is present in the primary cilia of renal epithelial cells where microtubular dynamics have been found to play a role in regulating TRPP2 channel activity [88]. Addition of the microtubular disrupter, colchicine to isolated ciliary membranes from epithelial cells was shown to abolish TRPP2 activity, whereas addition of the microtubular stabilizer paclitaxel increased channel activity.

Kinesin-2 mediates anterograde intraflagellar transport along the microtubule-based core (axoneme) of the primary cilium and is comprised of the two motor subunits (KIF3A and KIF3B) and a non-motor subunit (KAP3) [89]. KIF3A has been shown to colocalize with TRPP2 in the primary cilium and a physical interaction between the C-terminal domains of both proteins was identified [88]. Interestingly, addition of KIF3A but not KIF3B was found to sufficiently activate TRPP2 channel activity and/or stabilize TRPP2 in the activated state in isolated ciliary membranes reconstituted in a lipid bilayer system. KIF3B was also shown to associate with TRPP2 along with fibrocystin [90], a protein mutated in autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease (ARPKD) [91]. No direct interaction between TRPP2 and fibrocystin was observed, yet both proteins were found to reside in the same complex in the presence of KIF3B and colocalize in the primary cilium or perinuclear region. The C-terminus of fibrocystin was observed to stimulate purified TRPP2 activity only if KIF3B was part of the complex, whereas KIF3B alone had no effect on activity [90]. Together, these studies provide valuable insight into the regulation of TRPP2 function at the primary cilium and highlight a potential link between ADPKD and ARPKD.

10. TRPP2-channel complexes

10.1. Transient receptor potential canonical type 1 (TRPC1) channel

Based on sequence homology, TRP channels have been grouped into six categories (TRPC, TRPV, TRPM, TRPA, TRPP, and TRPML), all of which form cation-permeable channels that span the membrane six times [10]. In addition to forming homomeric channels as discussed previously, TRPP2 has been shown to interact with other channels to form heteromultimers [92]. TRPP2 directly associates with TRPC1 in transfected cells and in vitro [36]. This interaction is mediated by two distinct TRPP2 domains, the first of which constitutes a region of 73 aa in the C-terminal tail. This domain was shown to be sufficient but not necessary for association. Interestingly, the residues involved in binding TRPC1 are distinct from those involved in the interaction of TRPP2 and PKD1. Specifically, residue D886 in human TRPP2 mediates the interaction with TRPC1 but is not essential for interaction with PKD1 [36]. The second interaction domain is localized within the S2 and S5 transmembrane segments and includes a pore helical region between S5 and S6. TRPC proteins are thought to be activated by GPCR activation or internal Ca2+ store depletion, and the association of TRPP2 and TRPC1 suggests a role for TRPP2 in modulating Ca2+ entry in response to GPCR activation and/or store depletion.

Atomic force microscopy has been employed to study the interaction between TRPP2 and TRPC1. These studies determined TRPP2 and TRPC1 assemble as a homotetramer and predicted a TRPP2/TRPC1 subunit stoichiometry of 2:2 with alternating subunit arrangement [93]. TRP channel heteromultimerization can lead to the formation of channels with new biophysical properties or modes of activation/inhibition [92]. Supporting this notion, TRPP2/TRPC1 complexes were found to elicit distinct functional properties from the homomeric complexes [94]. Single-channel current analysis of TRPP2 revealed four intrinsic, nonstochastic subconductance states that were both pH-and voltage-dependent. Assessment of heteromeric TRPP2/TRPC1 channel complexes showed that low pH inhibited currents in the homomeric TRPP2 complex but failed to affect TRPP2 currents in the heteromeric TRPP2/TRPC1 complex. In contrast, amiloride abolished TRPP2 currents in both the homomeric and heteromeric complexes. Atomic force microscopy confirmed tetrameric topology for both homo- and heteromeric complexes, and demonstrated a difference in both the diameter and height between TRPP2 and TRPC1 homomeric complexes. These data suggest that the conductance of heteromultimeric TRP channel complexes depends on the monomeric contributions to the complex [94]. Overall, TRPP2 has been shown to physically and functionally interact with TRPC1 in multiple assays, but their interaction in vivo has not been elucidated. Trpc1−/− mice have been developed and are free of kidney cysts, suggesting that the TRPP2/TRPC1 complex may not be critical in the prevention of cyst formation. Therefore, this interaction could be important in mediating other extra-renal functions of TRPP2. Alternatively, since TRPP2 associates with TRPC1 via two distinct domains and the role of individual protein-protein interactions may have positive and negative functional effects, the in vivo effects of a specific protein-protein interaction can be best addressed by knocking out specific interactions rather than the entire protein.

10.2. Transient receptor potential vanilloid type 4 (TRPV4) channel

In addition to TRPC1, TRPP2 was also found to interact with TRPV4 [95]. Atomic force microscopy studies revealed TRPV4 assembles as a homotetramer, and that the TRPP2/TRPV4 heteromeric complex assembles identically to the TRPP2/TRPC1 complex. Interestingly, this finding indicates heteromeric TRP channels may share a common subunit arrangement [95].

Distorted [Ca2+]i signaling in ADPKD cells has been correlated to reduced TRPV4 activity and TRPV4-dependent Ca2+ influxes [96]. TRPP2 is required for cilia-mediated Ca2+ transients and has been shown to associate with TRPV4 to form a mechanosensitive sensor in the cilium [97]. TRPP2 alone lacks mechanosensitive properties and loss of TRPV4 in renal epithelial cells abolished flow-induced Ca2+ transients demonstrating that both TRPP2 and TRPV4 are essential components of the ciliary mechanosensor. However, TRPV4-deficient zebrafish and mice lack renal cysts, suggesting that ciliary flow sensing does not contribute to cystogenesis. Notably, TRPP2 has also been reported to form a complex with both TRPV4 and TRPC1 to mediate Ca2+ influx in response to fluid flow changes in primary cultured rat mesenteric artery endothelial cells. Several independent approaches demonstrated the formation of a heteromeric complex consisting of the three subunits. All subunits functionally contributed to Ca2+ permeation and the current mediated by TRPP2/TRPV4/TRPC1 was eliminated in vascular endothelial cells derived from Trpc1-null mice [98].

Endogenous TRPP2 and TRPV4 have been reported to form a 23-pS divalent cation-permeable non-selective ion channel at the apical membrane of renal principal cells of the collecting duct [99]. The rate of occurrence was higher in cells lacking cilia compared to ciliated cells. Knockdown of either protein increased the prevalence of the opposite channels activity, whereas knockdown of both proteins significantly decreased 23-pS channel activity. Consistent with these findings, another study showed in vivo that 23-pS channel activity is elevated with loss of cilia [100]. Apical channel activity was measured in isolated split-open cortical collecting ducts from adult conditional knockout mice with (Ift88flox/flox) or without (Ift88−/−) cilia. Channel activity from Ift88flox/flox mice was predominantly from epithelial Na+ channels, whereas with the loss of cilia, the predominant conductance was from 23-pS nonselective cation channels. Moreover, epidermal growth factor (EGF) was revealed to stimulate TRPP2/TRPV4 channel activity via EGF receptor (EGFR) signaling [99]. Apical EGF treatment resulted in a 64-fold increase in channel activity in cells lacking cilia and this increase in intracellular Ca2+ was associated with an increase in cell proliferation. Altogether, these studies support the implication of EGFR-mediated TRPP2/TRPV4 activity at the apical membrane of collecting duct cells that lack cilia in ADPKD-associated cell proliferation.

10.3. Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)

Studies in LLC-PK1 kidney epithelial cells have provided additional insight regarding the mechanism by which epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) signaling modulates TRPP2 channel activity [101]. TRPP2 overexpression was shown to increase epidermal growth factor (EGF)-induced inward currents while knockdown or expression of a pathogenic TRPP2 missense variant, D511V, abolished this response. Pharmacological experiments suggested that EGF-induced TRPP2 activation requires phospholipase C (PLC) and phosphoinositide 3kinase (PI3K). Pipette infusion of purified PIP2 suppressed the TRPP2-mediated effect on EGF-induced currents, whereas infusion of PIP3 had no effect. Further, the overexpression of type Iα phosphatidylinositol-4-phosphate 5-kinase [PIP(5)Kα], which increase PIP2 formation, suppressed EGF-induced conductance. In HEK293T cells, TRPP2 was shown to physically interact with PLC-γ2 and EGFR. These results indicate that EGF may induce TRPP2 activity by blocking channel inhibition by PIP2 at the plasma membrane. Supporting the modulation of TRPP2 by PIP2, activation of TRPP2 was shown to be mediated by an intramolecular interaction involving a π-cation interaction from a tryptophan residue (W201 in human TRPP2) in the segment preceding the first transmembrane segment and a positively charged residue in the TRP domain in the C-terminal domain. This intramolecular interaction is prevented by direct binding of PIP2 to the positively charged residue in the TRP domain, rendering the channel in the inactivated state. According to this model, depletion of PIP2 allows channel activation and stabilization in the activated state by the π-cation interaction [102].

Mammalian Diaphanous 1 (mDia1), a member of the RhoA GTPase-binding formin homology protein family, interacts with TRPP2 through binding of the TRPP2 C-terminus to the N-terminus of mDia1 [103]. TRPP2 and mDia1 colocalize to the plasma membrane and mitotic spindles in dividing cells, and knockdown of mDia1 results in loss of TRPP2 from spindles and altered intracellular Ca2+ release, suggesting that TRPP2 may be mediating intracellular Ca2+ signaling in dividing cells via an interaction with mDia1. Additional work on the TRPP2/mDia1 interaction revealed that mDia1 functions as an intracellular, voltage-dependent regulator of TRPP2 at the plasma membrane of kidney epithelial cells [104]. At resting potential, mDia1 maintains an autoinhibited state in which it binds and blocks TRPP2 activity. At positive potentials, RhoA-induced molecular switching of mDia1 to its activated state releases the block on TRPP2 enabling channel activation. Under physiological resting potentials, EGF-induced activation of Rho-A releases the mDia1-dependent block on TRPP2.

Altogether these studies highlight several mechanisms by which EGFR signaling may regulate TRPP2 channel activity. Through activation of PI3K and PLC-γ2, PIP2 levels are reduced and thus the activation threshold of TRPP2 is reduced. Additionally, activation of RhoA and the sequential activation of mDia1 removes the block on TRPP2 channel activity. During mitosis, mDia1 likely serves a role in trafficking of TRPP2 and indirectly regulates intracellular Ca2+ release.

10.4. Inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor (IP3R)

The interaction of TRPP2 and the inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor (IP3R), an intracellular Ca2+ channel in the ER, was first demonstrated using a Xenopus oocyte Ca2+ imaging system to explore the role of TRPP2 in IP3R-dependent Ca2+ signaling [38]. Overexpression of TRPP2 or IP3R prolonged the half-decay time (t1/2) of IP3-induced Ca2+ transients. In contrast, overexpression of the ADPKD-associated TRPP2 mutants, D511V and R742X, did not alter the t1/2, and TRPP2-D511V overexpression reduced the amplitude of IP3induced Ca2+ transients. Overexpression of the TRPP2 C-terminal fragment both reduced amplitude and prolonged the t1/2, and co-immunoprecipitation (co-IP) revealed a physical interaction between TRPP2 C-terminal domain and IP3R. Another study identified the molecular determinants of the TRPP2 and IP3R interaction to include an acidic cluster in the C-terminal tail of TRPP2 (aa 810–818) and a cluster of positively charged residues in the N-terminal ligand-binding domain of IP3R (aa 51–54) [105]. As a result of this interaction, TRPP2 potentiates IP3Rinduced Ca2+ release. Using ADPKD TRPP2 mutants, R740X and D509V, and competing peptides, TRPP2 was found to amplify the Ca2+ signal by a local Ca2+-induced Ca2+-release mechanism, only when the TRPP2/IP3R interaction was present. Authors proposed a model whereby IP3 production activates IP3R leading to a local rise in cytosolic Ca2+ that activates TRPP2 as a Ca2+-induced Ca2+-release channel, and the TRPP2/IP3R is necessary to facilitate Ca2+-induced Ca2+-release by TRPP2. Together, these studies suggest that TRPP2 and IP3R interact and modulate intracellular Ca2+ signaling, and mutations that disrupt this interaction may contribute to altered Ca2+ signaling and thereby contribute to ADPKD pathogenesis.

10.5. Ryanodine receptor (RyR2)

In addition to its interaction with IP3R in the ER, TRPP2 has been shown to interact with the cardiac ryanodine receptor (RyR2) in the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) of mouse cardiomyocytes [37]. These studies revealed that the N-terminus of TRPP2 binds RyR2, whereas its C-terminus only binds to RyR2 in its open state. Electrophysiological experiments in lipid bilayers revealed that the C-terminus of TRPP2 blocked RyR2 channel activity in the presence of Ca2+. Pkd2−/− cardiomyocytes showed higher frequency of spontaneous Ca2+ oscillations, reduced Ca2+ release from SR stores, reduced Ca2+ content in the SR, and altered kinetics of Ca2+ transients from RyR2 compared to Pkd2+/+ cardiomyocytes. This study highlights the role TRPP2 as an important functional regulator of RyR2. Additionally, this work suggests mutations in TRPP2 that impede this regulation through disruption of the TRPP2RyR2 interaction could lead to altered Ca2+ signaling in the heart. Downstream consequences of this phenomenon may account for the cardiovascular phenotypes observed in ADPKD patients.

TRPP2 interacts with both IP3R and RyR2 to influence intracellular Ca2+ signaling and maintain cellular Ca2+ homeostasis, yet neither of these proteins regulate TRPP2 channel activity. Syntaxin-5 (Stx5) has been identified as a TRPP2-interacting partner responsible for regulating the inactive state of TRPP2 at the ER [106]. Syntaxins function in vesicle targeting and fusion and have been shown to interact with and regulate the channel activity of a number of transport proteins [107–110]. The interaction of TRPP2 and Stx5 was confirmed in vivo in native kidney tissues. In vitro binding assays showed a direct interaction between Stx5 and TRPP2 mediated by the t-SNARE region of Stx5 and N-terminal aa 52–72 of TRPP2. Single channel analysis showed that Stx5 binding inactivates TRPP2 channel activity in a dosedependent fashion. Epithelial cells overexpressing TRPP2 mutants unable to bind Stx5 showed increased baseline cytosolic Ca2+ levels, decreased ER Ca2+ stores, and reduced Ca2+ release from ER stores upon vasopressin stimulation. Cells lacking TRPP2 showed reduced cytosolic Ca2+ levels. This work provides insight into the regulation of TRPP2 at the ER membrane and suggests a possible mechanism to prevent Ca2+ leak from intracellular stores.

11. TRPP2 interactions facilitate trafficking to and from the plasma membrane

Protein phosphorylation is crucial in regulating protein function by directing trafficking, targeting, retention and much more [111]. Regulation of TRPP2 activity requires tight control of these processes to ensure proper distribution at multiple cellular locations. An important role has been demonstrated for phosphofurin acidic cluster sorting proteins, PACS-1 and PACS-2, in directing the subcellular localization of TRPP2 [112]. These adaptor proteins recognize an acidic cluster in the C-terminal domain of TRPP2, and binding is dependent on the phosphorylation of TRPP2 at S812 by the protein kinase casein kinase 2 (CK2). Interaction with PACS-2 directs TRPP2 from the Golgi apparatus to the ER, whereas PACS-1 directs TRPP2 from endosomal compartments back to the trans-Golgi network (TGN). Blocking the binding to both PACS-1 and PACS-2 or inhibition of CK2 localizes TRPP2 to the plasma membrane.

Hidaka et al. [113] identified a novel protein known as PIGEA-14 (polycystin-2 interactor, Golgi- and ER-associated protein with a molecular mass of 14 kDa) through a yeast two-hybrid screen using the C-terminus of TRPP2. This group showed that the amino acid sequence G833S923 of TRPP2 is sufficient to interact with PIGEA14, and additionally found that PIGEA14 could interact with GM130, a component of the cis-compartment of the Golgi apparatus. In LLC-PK1 cells, expression of either PIGEA-14 or TRPP2 revealed a reticular distribution, whereas upon co-expression, both proteins were redistributed to the trans-Golgi network (TGN). These results suggest PIGEA-14 plays an important role in regulating the intracellular trafficking of TRPP2 from the ER to the TGN. A more recent study investigated whether PIGEA14 might be influenced by the phosphorylation state of TRPP2 [114]. Binding affinities for the interaction of PIGEA14 with the C-terminal domain of both wild type and a pseudophosphorylated TRPP2 mutant (S812D) were quantified. These results showed a dissociation constant of wild type TRPP2 to PIGEA14 in the 10 nM range, suggestive of a very specific interaction, and this interaction was two-fold higher than that of the pseudophosphorylated mutant. Based on these findings, this group proposed a trafficking model whereby S812-phosphorylated TRPP2 binds with high affinity to PACS-2 and remains located at the ER. Upon dephosphorylation, the binding affinity to PACS-2 is decreased and TRPP2 is released. PIGEA-14 could then bind to TRPP2, as binding affinity would be high, to facilitate forward trafficking.

Identification of a different phosphorylation site for TRPP2 within the N-terminal domain (S76) has also been reported, and phosphorylation at this site was shown to be important for regulating TRPP2 expression at the plasma membrane [115]. S76 phosphorylation was shown to occur through glycogen synthase kinase 3 (GSK-3) by recognition of a conserved consensus sequence (S76/S80). In the presence of GSK-3 inhibitors, the lateral plasma membrane pool of endogenous TRPP2 was found to redistribute into an intracellular compartment in MDCK cells, yet no change was shown to occur in the localization to the primary cilium. Using a pkd2 antisense morpholino oligonucleotide (pkd2ATGMO), which has been shown to induce a cystic phenotype in zebrafish embryos [116], this work showed that co-injection of wild type human PKD2 but not a PKD2-S76A/S80A mutant mRNA could rescue this phenotype. These findings indicate an important role for GSK-3 phosphorylation of TRPP2 in both plasma membrane localization and in normal kidney development.

Lastly, a recent study by Feng et al. [117] identified TRPP2 as cargo of a sorting nexin 3 (SNX3)-retromer complex. TRPP2 was revealed to bind two isoforms of SNX3, SNX3–162 and a novel isoform, SNX3–102, that binds directly to TRPP2. SNX3–162 was shown to associate with TRPP2 via the core retromer protein VPS35, which directly binds to the cytosolic N-terminal region of TRPP2. Expression of GFP-tagged SNX3 isoforms revealed localization of SNX3–162 to EEA1-positive early endosomes, whereas SNX3–102 colocalized with the adaptor protein-2 (AP2) in clathrin-coated endocytic vesicles. Knockdown of SNX3 or VPS35 increased plasma membrane expression of endogenous PKD1 and TRPP2 in vitro and in vivo, and increased WNT-activated TRPP2-dependent whole-cell currents proportional to the increase in the plasma membrane expression. These findings indicate that a retromer complex containing SNX3 regulates the plasma membrane expression and function of the PKD1/TRPP2 complex. On the basis of these findings, this group proposed that SNX3–102 may bind to TRPP2 and AP2/clathrin to cluster TRPP2 into clathrin-coated endocytic vesicles. Upon endocytosis, vesicles fuse with early endosomes at which point SNX3–162 and VPS35 interact with TRPP2 to regulate its fate along with that of PKD1.

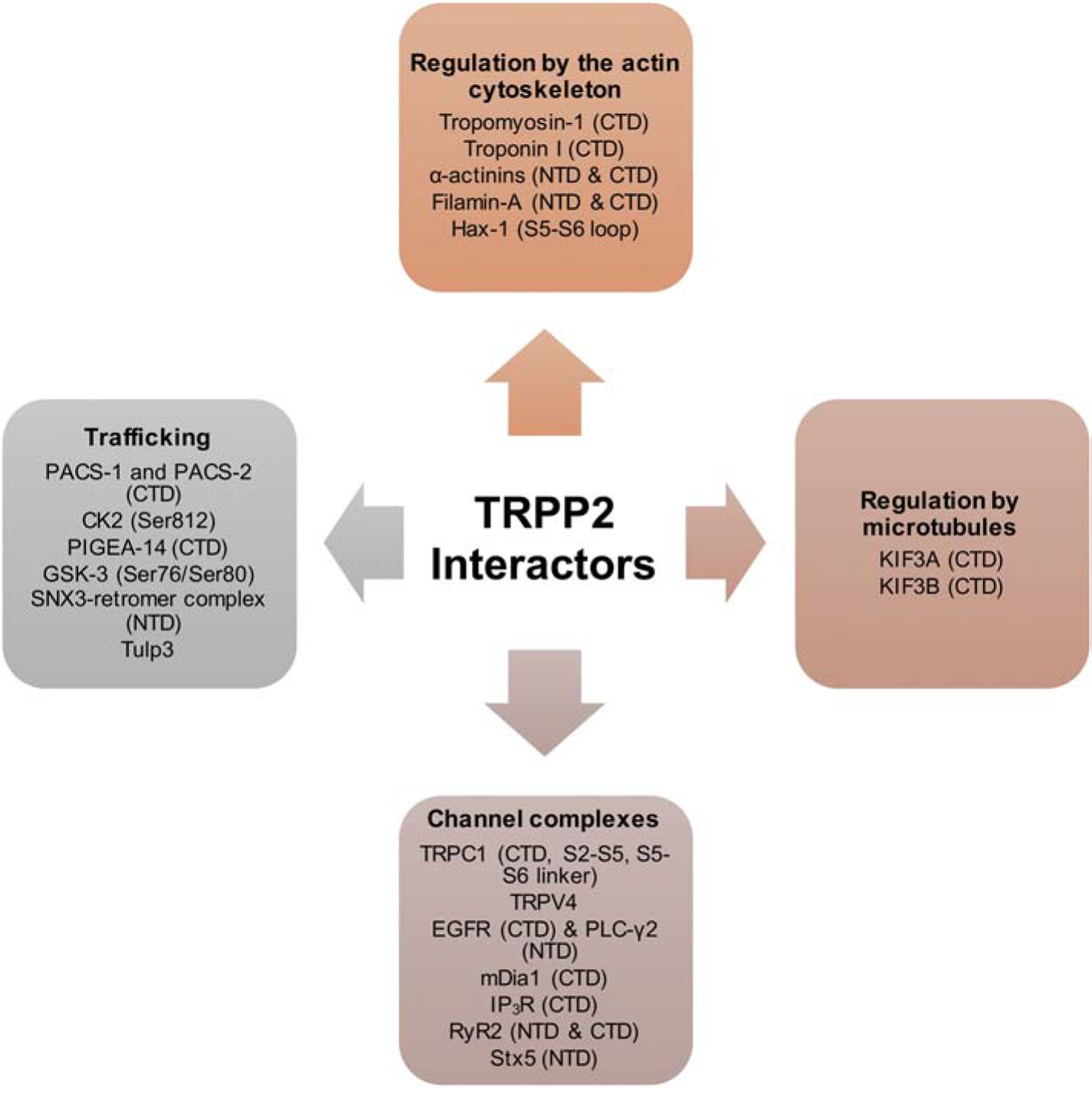

12. Protein-protein interactions regulating trafficking of PKD1 and TRPP2 to the primary cilium

PKD1 and TRPP2 are both present in the primary cilium and several studies showed that their presence there is regulated by protein-protein interactions and mechanisms that might be distinct from mechanisms regulating their localization at the plasma membrane [118]. An early step controlling the trafficking of PKD1/TRPP2 complex from the ER to the TGN involves a physical interaction with Rabep1 at the ER following cleavage at the GPS. Rabep1 binds the PKD1 C-terminal tail and this interaction is critical in delivering the complex to the TGN, from which point can travel to the base of the cilium via microtubules [119]. Once at the base of the cilium, vesicles containing transmembrane proteins will have to cross a physical barrier formed partially by the BBSome at the base of the cilium. The BBSome is a large multiprotein complex at the base of the primary cilium that controls entry of transmembrane proteins into the cilium [120–123]. The PKD1 C-terminal tail physically interacts with BBS1, BBS4, BBS5, and BBS8, but binding specifically to BBS1 is critical for mediating PKD1 targeting to the primary cilium [124]. In addition to binding to BBS proteins, the site at which PP1α binds PKD1 in the C-terminal tail has been shown to include a ciliary targeting sequence, and this interaction is essential for targeting it to the primary cilium [125]. It would be interesting to know how the function of PP1α interfaces with the function of BBS proteins in mediating PKD1 targeting to the primary cilium. Another important regulator of trafficking TRPP2, and possibly PKD1 to the primary cilium is Tulp3 [126]. However, whether this function of Tulp3 is mediated via direct protein-protein interactions with PKD1 or TRPP2 is not clear [127]. Overall, there is strong evidence supporting the presence of PKD1 and TRPP2 at the primary cilium, which is achieved by multiple protein-protein interactions controlling the trafficking of this complex from the ER to the primary cilium. Like PKD1, numerous proteins within the cell have been reported to interact with TRPP2 (Fig. 4). These interactions have been proposed to serve a number of roles, including trafficking TRPP2 to multiple cellular locations, regulating channel activity, linking TRPP2 to the cytoskeleton, and forming large multi-channel complexes. These associations may couple TRPP2 to different signaling modalities and allow it to serve functions independently of PKD1.

Figure 4. Diagrammatic representation of TRPP2 interactors.

Known TRPP2 domains involved in binding are shown in parentheses. Abbreviations: NTD, N-terminal domain; CTD, C-terminal domain.

13. Concluding remarks

Over the last 20 years, numerous protein-protein interactions involving PKD1, TRPP2, or both proteins together have been identified. By definition, protein-protein interactions have been demonstrated biochemically using an array of assays testing direct or indirect interactions. Fewer interactions have been tested functionally using suitable cell culture systems. Even fewer interactions have been confirmed genetically using model systems such as Xenopus, zebrafish, and the mouse. A challenge for the future would be to understand the biological role(s) of these interactions and integrate this knowledge into a mechanistic framework of how Polycystins function in their native environment/tissue. Since PKD1 and TRPP2 have functions that go far and beyond the few organs affected in ADPKD patients, modulation of their functions by protein-protein interactions can have implications in numerous processes involving the function of Polycystins alone or as a complex in a wide range of tissues.

Highlights.

Protein-protein interactions regulate the function, localization, and stability of the Polycystin complex.

Naturally occurring mutations in families with ADPKD disrupt a subset of protein-protein interactions highlighting the relevance of protein interactions in ADPKD.

Studies of protein-protein interactions has provided mechanistic insights of the function of wild type and pathogenic forms of Polycystins.

Targeting specific protein-protein interactions can lead to new pharmacological approaches to the treatment of ADPKD and pathologies associated with the Polycystin complex.

Acknowledgements

Research on Polycystins and ADPKD in the Tsiokas laboratory is funded by DK59599 and DK117654 and the John S. Gammill Endowed Chair in Polycystic Kidney Disease.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- 1.Torres VE and Harris PC, Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease: the last 3 years. Kidney Int, 2009. 76(2): p. 149–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chebib FT and Torres VE, Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease: Core Curriculum 2016. Am J Kidney Dis, 2016. 67(5): p. 792–810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Takiar V and Caplan MJ, Polycystic kidney disease: pathogenesis and potential therapies. Biochim Biophys Acta, 2011. 1812(10): p. 1337–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Colbert GB, et al. , Update and review of adult polycystic kidney disease. Dis Mon, 2019: p. 100887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.The European Polycystic Kidney Disease, C., The polycystic kidney disease 1 gene encodes a 14 kb transcript and lies within a duplicated region on chromosome 16. Cell, 1994. 77(6): p. 881–894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mochizuki T, et al. , PKD2, a Gene for Polycystic Kidney Disease That Encodes an Integral Membrane Protein. Science, 1996. 272(5266): p. 1339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Porath B, et al. , Mutations in GANAB, Encoding the Glucosidase IIα Subunit, Cause Autosomal-Dominant Polycystic Kidney and Liver Disease. American journal of human genetics, 2016. 98(6): p. 1193–1207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cornec-Le Gall E, et al. , Monoallelic Mutations to DNAJB11 Cause Atypical Autosomal-Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease. Am J Hum Genet, 2018. 102(5): p. 832–844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sandford R, et al. , Comparative Analysis of the Polycystic Kidney Disease 1 (PKD1) Gene Reveals an Integral Membrane Glycoprotein with Multiple Evolutionary Conserved Domains. Human Molecular Genetics, 1997. 6(9): p. 1483–1489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ramsey IS, Delling M, and Clapham DE, AN INTRODUCTION TO TRP CHANNELS. Annual Review of Physiology, 2006. 68(1): p. 619–647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Consortium TIPKD, Polycystic kidney disease: the complete structure of the PKD1 gene and its protein. The International Polycystic Kidney Disease Consortium. Cell, 1995. 81(2): p. 289–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ponting CP, Hofmann K, and Bork P, A latrophilin/CL-1-like GPS domain in polycystin-1. Curr Biol, 1999. 9(16): p. R585–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hughes J, et al. , The polycystic kidney disease 1 (PKD1) gene encodes a novel protein with multiple cell recognition domains. Nature Genetics, 1995. 10(2): p. 151–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moy GW, et al. , The sea urchin sperm receptor for egg jelly is a modular protein with extensive homology to the human polycystic kidney disease protein, PKD1. J Cell Biol, 1996. 133(4): p. 809–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Trudel M, Yao Q, and Qian F, The Role of G-Protein-Coupled Receptor Proteolysis Site Cleavage of Polycystin-1 in Renal Physiology and Polycystic Kidney Disease. Cells, 2016. 5(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Arac D, et al. , A novel evolutionarily conserved domain of cell-adhesion GPCRs mediates autoproteolysis. EMBO J, 2012. 31(6): p. 1364–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Su Q, et al. , Structure of the human PKD1-PKD2 complex. Science, 2018. 361(6406). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bateman A and Sandford R, The PLAT domain: a new piece in the PKD1 puzzle. Current Biology, 1999. 9(16): p. R588–S2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Douguet D, Patel A, and Honore E, Structure and function of polycystins: insights into polycystic kidney disease. Nat Rev Nephrol, 2019. 15(7): p. 412–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Parnell SC, et al. , The Polycystic Kidney Disease-1 Protein, Polycystin-1, Binds and Activates Heterotrimeric G-Proteins in Vitro. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications, 1998. 251(2): p. 625–631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Qian F, et al. , PKD1 interacts with PKD2 through a probable coiled-coil domain. Nature Genetics, 1997. 16(2): p. 179–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bycroft M, et al. , The structure of a PKD domain from polycystin-1: implications for polycystic kidney disease. Embo J, 1999. 18(2): p. 297–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pletnev V, et al. , Rational proteomics of PKD1. I. Modeling the three dimensional structure and ligand specificity of the C_lectin binding domain of Polycystin-1. J Mol Model, 2007. 13(8): p. 891–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oatley P, et al. , Atomic force microscopy imaging reveals the domain structure of polycystin-1. Biochemistry, 2012. 51(13): p. 2879–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shen PS, et al. , The Structure of the Polycystic Kidney Disease Channel PKD2 in Lipid Nanodiscs. Cell, 2016. 167(3): p. 763–773.e11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grieben M, et al. , Structure of the polycystic kidney disease TRP channel Polycystin-2 (PC2). Nat Struct Mol Biol, 2017. 24(2): p. 114–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yang Y and Ehrlich BE, Structural studies of the C-terminal tail of polycystin-2 (PC2) reveal insights into the mechanisms used for the functional regulation of PC2. J Physiol, 2016. 594(15): p. 4141–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhu J, et al. , Structural model of the TRPP2/PKD1 C-terminal coiled-coil complex produced by a combined computational and experimental approach. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2011. 108(25): p. 10133–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Celic A, et al. , Domain mapping of the polycystin-2 C-terminal tail using de novo molecular modeling and biophysical analysis. J Biol Chem, 2008. 283(42): p. 28305–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Keeler C, et al. , An explicit formulation approach for the analysis of Ca2+ binding to EF-hand proteins using isothermal titration calorimetry. Biophys J, 2013. 105(12): p. 284353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Petri ET, et al. , Structure of the EF-hand domain of polycystin-2 suggests a mechanism for Ca2+-dependent regulation of polycystin-2 channel activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2010. 107(20): p. 9176–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kuo IY, et al. , The number and location of EF hand motifs dictates the Ca2+ dependence of polycystin-2 function. FASEB J, 2014. 28(5): p. 2332–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Streets AJ, et al. , Protein kinase D-mediated phosphorylation of polycystin-2 (TRPP2) is essential for its effects on cell growth and Ca2+ channel activity. Mol Biol Cell, 2010. 21(22): p. 3853–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Streets AJ, et al. , Hyperphosphorylation of polycystin-2 at a critical residue in disease reveals an essential role for polycystin-1-regulated dephosphorylation. Hum Mol Genet, 2013. 22(10): p. 1924–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tsiokas L, et al. , Homo- and heterodimeric interactions between the gene products of PKD1 and PKD2. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 1997. 94(13): p. 6965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tsiokas L, et al. , Specific association of the gene product of PKD2 with the TRPC1 channel. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 1999. 96(7): p. 3934–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Anyatonwu GI, et al. , Regulation of ryanodine receptor-dependent Ca2+ signaling by polycystin-2. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2007. 104(15): p. 6454–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li Y, et al. , Polycystin 2 interacts with type I inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor to modulate intracellular Ca2+ signaling. J Biol Chem, 2005. 280(50): p. 41298–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yu Y, et al. , Structural and molecular basis of the assembly of the TRPP2/PKD1 complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2009. 106(28): p. 11558–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Behn D, et al. , Quantifying the interaction of the C-terminal regions of polycystin-2 and polycystin-1 attached to a lipid bilayer by means of QCM. Biophys Chem, 2010. 150(13): p. 47–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Molland KL, et al. , Identification of the structural motif responsible for trimeric assembly of the C-terminal regulatory domains of polycystin channels PKD2L1 and PKD2. Biochem J, 2010. 429(1): p. 171–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hanaoka K, et al. , Co-assembly of polycystin-1 and −2 produces unique cation-permeable currents. Nature, 2000. 408(6815): p. 990–994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kim S, et al. , The polycystin complex mediates Wnt/Ca(2+) signalling. Nat Cell Biol, 2016. 18(7): p. 752–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Delmas P, et al. , Constitutive activation of G-proteins by polycystin-1 is antagonized by polycystin-2. J Biol Chem, 2002. 277(13): p. 11276–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Parnell SC, et al. , Polycystin-1 activation of c-Jun N-terminal kinase and AP-1 is mediated by heterotrimeric G proteins. J Biol Chem, 2002. 277(22): p. 19566–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yanamadala V, et al. , Galpha12 stimulates apoptosis in epithelial cells through JNK1mediated Bcl-2 degradation and up-regulation of IkappaBalpha. J Biol Chem, 2007. 282(33): p. 24352–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yu W, et al. , Polycystin-1 protein level determines activity of the Galpha12/JNK apoptosis pathway. J Biol Chem, 2010. 285(14): p. 10243–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yu W, et al. , Identification of polycystin-1 and Galpha12 binding regions necessary for regulation of apoptosis. Cell Signal, 2011. 23(1): p. 213–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wu Y, et al. , Galpha12 is required for renal cystogenesis induced by Pkd1 inactivation. J Cell Sci, 2016. 129(19): p. 3675–3684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kwon M, et al. , G-protein signaling modulator 1 deficiency accelerates cystic disease in an orthologous mouse model of autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2012. 109(52): p. 21462–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kim E, et al. , Interaction between RGS7 and polycystin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 1999. 96(11): p. 6371–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Parnell SC, et al. , A mutation affecting polycystin-1 mediated heterotrimeric G-protein signaling causes PKD. Hum Mol Genet, 2018. 27(19): p. 3313–3324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kwak M, et al. , Galphai-mediated TRPC4 activation by polycystin-1 contributes to endothelial function via STAT1 activation. Sci Rep, 2018. 8(1): p. 3480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhang B, Tran U, and Wessely O, Polycystin 1 loss of function is directly linked to an imbalance in G-protein signaling in the kidney. Development, 2018. 145(6). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Alberts B, et al. , Molecular biology of the cell (Sixth Edition) 2015: W. W. Norton & Company. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Huan Y and van Adelsberg J, Polycystin-1, the PKD1 gene product, is in a complex containing E-cadherin and the catenins. J Clin Invest, 1999. 104(10): p. 1459–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]