Abstract

Purpose:

Few patients with metastatic triple-negative breast cancer (mTNBC) benefit from immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs). Based on immunotherapy response correlates in other cancers, we evaluated whether high tumor mutational burden (TMB) ≥10 nonsynonymous mutations/megabase and PTEN alterations, defined as nonsynonymous mutations or 1 or 2 copy deletions, were associated with clinical benefit to anti-PD-1/ L1 therapy in mTNBC.

Experimental Design:

We identified patients with mTNBC, who consented to targeted DNA sequencing and were treated with ICIs on clinical trials between April 2014 and January 2019 at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute (Boston, MA). Objective response rate (ORR), progression-free survival (PFS), and overall survival (OS) were correlated with tumor genomic features.

Results:

Sixty-two women received anti-PD-1/L1 inhibitors alone (23%) or combined with targeted therapy (19%) or chemotherapy (58%). High TMB (18%) was associated with significantly longer PFS (12.5 vs. 3.7 months; p=0.04); while PTEN alterations (29%) were associated with significantly lower ORR (6% vs. 48%; p=0.01), shorter PFS (2.3 vs. 6.1 months; p=0.01), and shorter OS (9.7 vs. 20.5 months; p=0.02). Multivariate analyses confirmed that these associations were independent of performance status, prior lines of therapy, therapy regimen, and visceral metastases. The survival associations were additionally independent of PD-L1 in patients with known PD-L1 and were not found in mTNBC cohorts treated with chemotherapy (n = 90) and non-ICI regimens (n = 169).

Conclusions:

Among patients with mTNBC treated with anti-PD-1/L1 therapies, high TMB and PTEN alterations were associated with longer and shorter survival, respectively. These observations warrant validation in larger datasets.

Keywords: breast cancer, immune checkpoint inhibitors, immunotherapy, triple-negative breast cancer, tumor mutational burden, PTEN alterations

Statement of Translational Relevance

This study investigates whether high tumor mutational burden (TMB) and PTEN alterations affect response to anti-PD-1/L1 therapies among patients with metastatic triple-negative breast cancer (mTNBC). High TMB and PTEN alterations correlate with clinical responses to immune checkpoint inhibitors in other tumors, but these associations have not been well studied in breast cancer. In this cohort of 62 women with mTNBC treated with anti-PD-1/L1 therapies, high TMB was associated with improved progression-free survival, while PTEN alterations were associated with reduced responses and progression-free and overall survival. These associations were independent of clinical confounders, as well as PD-L1 in patients with known PD-L1, and were not found in patients treated with non-immunotherapy regimens. Overall, high TMB and PTEN alterations were associated with better and worse outcomes, respectively, among patients with mTNBC treated with anti-PD-1/L1 therapies. These results warrant validation in larger prospective studies, including ongoing trials investigating whether AKT inhibitors reverse resistance to PD-1 blockade.

Introduction

Patients with metastatic triple-negative breast cancer (mTNBC) have limited treatment options and a poor prognosis with a median overall survival of 13 to 18 months.1 Despite the success of PD-1/L1 inhibitors in other cancers, their single-agent efficacy in mTNBC is low: monotherapy responses range from 5% in unselected cohorts to 25% in patients with PD-L1-positive and/or treatment-naïve disease.2–5

Recently the IMpassion130 study showed that adding atezolizumab to nab-paclitaxel improved progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) in patients with treatment-naïve PD-L1-positive mTNBC.6 Based on these data, this combination was granted accelerated approval for the treatment of mTNBC with ≥ 1% PD-L1 expression on immune cells.6 However, there are still open questions surrounding the broad utility of PD-L1 testing for selecting patients for immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), and additional biomarkers to predict benefit are being investigated.

Given its close association with neoantigen burden and T-cell infiltration,7–10 tumor mutational burden (TMB) is one marker of tumor antigenicity.11, 12 A growing body of evidence has shown that high TMB correlates with response to PD-1/L1 inhibitors,13–18 but not non-ICI therapies,18 across different cancer types. Prior work has also shown that loss of the tumor suppressor PTEN may be linked to poor responses to PD-1 blockade in patients with melanoma and uterine leiomyosarcoma19, 20 and PTEN is frequently altered in TNBC.21 However, in mTNBC, data about the relationship of high TMB and PTEN alterations with immunotherapy response are lacking. Therefore, the aim of this work was to evaluate the association of high TMB and PTEN alterations with ICI efficacy in patients with mTNBC.

Methods

Study Cohort

We included patients with mTNBC, defined as the absence of HER2 amplification and estrogen and progesterone receptor expression (<1%), treated with anti-PD-1/L1 therapy as monotherapy or in combination with chemotherapy or targeted therapy at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute. Eligible patients prospectively provided written consent for research tumor genomic sequencing under protocol #11–104 and underwent targeted DNA sequencing (OncoPanel) on either an archival metastatic (47%), primary (45%), local recurrence (6%), or unknown (2%) tumor sample. This current project was performed after receiving approval by the Dana-Farber/Harvard Cancer Center Institutional Review Board (DF/HCC Protocol #18–082) and conducted in accordance with the ethical guidelines outlined by the Belmont Report.

Genomic and PD-L1 Assessment

Performed in a Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments-certified laboratory environment, OncoPanel uses targeted exome sequencing to detect copy number alterations, single nucleotide variants, and translocations across the full coding regions and selected intronic regions of a predefined subset of cancer-related genes with tumor-derived DNA.22 In this study, the majority of patients (n=44) had testing done using OncoPanel version 2,23 which targets the full coding regions or selected intronic regions of 335 genes (exonic coverage region = 0.82 megabase [Mb]). Four patients were assessed with OncoPanel version 1,24, 25 which targets 305 genes (exonic coverage region = 0.75 Mb), and 14 patients were evaluated with OncoPanel version 3,22 targeting 507 genes (exonic coverage region = 1.3 Mb). TMB was calculated as the number of nonsynonymous somatic mutations per megabase of exonic sequence data covered by each panel. All nonsynonymous mutations, including nonsense, missense, frame-shift, splice site, and nonstop changes, were considered. High TMB was defined as ≥10 mutations/Mb, and PTEN alterations were defined as nonsynonymous mutations or 1 or 2 copy deletions, based on prior work showing that partial PTEN deletions are associated with poor prognosis in breast cancer.26 All patients but one had OncoPanel performed on samples collected before exposure to immunotherapy.

PD-L1 expression was centrally evaluated (Q2 Solutions, Valencia, CA) during screening on patients treated with pembrolizumab (n = 37) using the PD-L1 IHC22C3 pharmDx kit (Agilent, Carpinteria, CA). Expression was measured by the combined positive score (CPS), defined as the ratio of PD-L1-positive cells (tumor cells, lymphocytes, and macrophages) to the total number of tumor cells. PD-L1 positivity was defined as CPS > 1.

Statistical Analysis

Responses were prospectively assessed by Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) version 1.1 during each clinical trial. PFS was defined as the date of starting immunotherapy to the date of progression, death, or last follow-up. OS was defined as the date of starting immunotherapy until the date of death or last follow-up. Patients alive and without progression at last follow-up were censored for PFS, and those still alive were censored for OS. The associations of high TMB and PTEN alterations with objective response rate (ORR), PFS, and OS were assessed with logistic regression for ORR and the Kaplan-Meier method, log-rank tests, and Cox proportional hazards regression for PFS and OS. Multivariate regression models adjusted for the following clinical factors: Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status (ECOG PS) at trial enrollment (≥1 versus 0), therapy regimen (monotherapy versus combination therapy, which showed the same significant associations as adjustment by individual therapy regimen, data not shown), number of prior systemic metastatic therapies (≥1 versus 0), and presence of visceral metastasis (yes versus no). Analyses were performed in RStudio Version 1.2.5001.

Results

Patient Characteristics

Between April 2014 and January 2019, 62 women with mTNBC met the inclusion criteria for this analysis. These women were enrolled on 6 different clinical trials with anti-PD-1/L1 therapy: 14 (23%) patients received ICIs as monotherapy (pembrolizumab [n=7, NCT02447003]; atezolizumab [n=7; NCT01375842]), and 48 (77%) received ICIs in combination with chemotherapy (pembrolizumab plus eribulin [n=30; NCT02513472]; atezolizumab plus nab-paclitaxel [n=6; NCT01633970]) or targeted therapy (nivolumab plus cabozantinib [n=9; NCT03316586]; pembrolizumab plus niraparib [n=3; NCT02657889]). At baseline, the median age was 55 years (range 32–76); 68% had an ECOG PS of 0; 74% had visceral metastasis; and 60% had received one or more prior systemic therapies for metastatic disease (Table 1). The median follow-up was 13.5 months, and there were 54 progression events and 44 deaths. Eight patients remained free of disease progression: 3 patients continued on immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy, 3 stopped treatment per protocol after 2 years of therapy, and 2 stopped due to toxicity. Overall, the median PFS and OS for the entire cohort were 4.2 and 16.0 months, respectively.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics

| Characteristic | Total (n = 62) | Not High TMB (n = 50) | High TMB (n = 12) | PTEN WT (n = 44) | PTEN Altered (n = 18) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, yrs, median (range) | 55 (32–76) | 55 (32–71) | 58 (42–76) | 56 (32–76) | 52 (37–76) |

| Female, N (%) | 62 (100) | 50 (100) | 12 (100) | 44 (100) | 18 (100) |

| ECOG-PS, N (%) | |||||

| 0 | 42 (68) | 32 (64) | 10 (83) | 31 (70) | 11 (61) |

| 1 | 20 (32) | 18 (36) | 2 (17) | 13 (30) | 7 (39) |

| Visceral metastases | 46 (74) | 35 (70) | 11 (92) | 31 (70) | 15 (83) |

| Prior therapies for metastatic disease | |||||

| Median (range) | 1 (0–6) | 1 (0–6) | 1 (0–2) | 1 (0–6) | 1 (0–6) |

| 0, N (%) | 25 (40) | 20 (40) | 5 (42) | 17 (39) | 8 (44) |

| 1, N (%) | 19 (31) | 15 (30) | 4 (33) | 14 (32) | 5 (28) |

| 2, N (%) | 13 (21) | 10 (20) | 3 (25) | 10 (23) | 3 (17) |

| ≥3, N (%) | 5 (8) | 5 (10) | 0 (0) | 3 (7) | 2 (11) |

| Previous therapy, N (%) | |||||

| Neo(adjuvant) therapy | 57 (92) | 64 (92) | 11 (92) | 41 (93) | 16 (89) |

| Taxanes | 56 (90) | 44 (88) | 12 (100) | 39 (89) | 17 (94) |

| Anthracycline | 51 (82) | 40 (80) | 11 (92) | 36 (82) | 15 (83) |

| Regimen, N (%) | |||||

| Monotherapy | 14 (23) | 10 (20) | 4 (33) | 12 (27) | 2 (11) |

| Combination | 49 (77) | 40 (80) | 8 (67) | 32 (73) | 16 (89) |

| PD-L1 statusa, N (%) | |||||

| Positive | 14 (38) | 11 (41) | 3 (30) | 11 (42) | 3 (27) |

| Negative | 23 (62) | 16 (59) | 7 (70) | 15 (58) | 8 (73) |

| ORR (%) | 35 | 30 | 58 | 48 | 6 |

The PD-L1 analysis included 37 patients.

Abbreviations: ECOG-PS: Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; ORR: objective response rate; TMB: tumor mutational burden; WT: wild type; yrs: years

TMB, PTEN Alterations, and PD-L1 Status

The median TMB was 6 mutations/Mb, and 12 (18%) patients were classified as having high TMB. The most commonly mutated genes were TP53 (51; 82%), BRCA1 (10; 16%), and ATM (8; 13%; eFigure 1 in the Supplement). A total of 18 (29%) patients had PTEN alterations, including 10 patients with 1 copy deletions, 6 patients with nonsynonymous alterations, 1 patient with a 2 copy deletion, and 1 patient with a 1 copy deletion and a nonsynonymous alteration. Of the 18 patients with PTEN alterations, 3 also had high TMB. Patients with PTEN alterations had the same mean TMB (7.5 vs 7.3 mutations/Mb) and a higher median TMB (8.2 vs. 5.3 mutations/Mb) than patients without PTEN alterations.

PD-L1 expression was assessed on 37 tumors and was positive in 14 (38%) cases (Table 1). The cohort of patients with known PD-L1 status was generally representative of the overall cohort (eTable 1 in the Supplement), except for a slightly higher portion of patients receiving immunotherapy as first-line treatment for metastatic disease (54% vs. 40% in the overall cohort). The ORR was numerically higher in PD-L1-positive tumors (57%) versus PD-L1-negative tumors (35%; p=0.3 by Fisher’s exact). Among tumors with high TMB and known PD-L1 status (n=10), 3 (30%) were PD-L1 positive, while among those without high TMB (n=27), 11 (41%) tumors were PD-L1 positive (p=0.7 by Fisher’s exact). The median TMB was also not statistically different between patients with PD-L1-positive and negative tumors (Wilcoxon test p=0.7; eFigure 2 in the Supplement). Likewise, among tumors with PTEN alterations and known PD-L1 status, 3 (27%) were PD-L1 positive, while among those without PTEN alterations, 11 (42%) tumors were PD-L1 positive (p=0.5 by Fisher’s exact).

High TMB and PTEN Alterations Associate with ORR, PFS, and/or OS in ICI Cohort

The ORR was numerically higher for patients with high TMB (58%) versus those with low TMB (30%; p=0.09 by Fisher’s exact) and significantly lower for patients with PTEN alterations (6%) versus those without PTEN alterations (48%; p=0.001 by Fisher’s exact). Univariate analyses showed that patients with high TMB had a 3.3 times higher odds of response than patients without high TMB (odds ratio [OR] 3.27, 95% CI 0.90–12.67, p=0.07), and patients with PTEN alterations had a 94% lower odds of response than patients without PTEN alterations (OR 0.06, 95% CI 0.003–0.36, p=0.01). In multivariate analyses, patients with high TMB had a 4 times higher odds of response than patients without high TMB (OR 4.32, 95% CI 1.05–19.89, p=0.05), and patients with PTEN alterations had a 94% lower odds of response than patients without PTEN alterations (OR 0.06, 95% CI 0.003–0.34, p=0.01), independent of clinical factors. In the 37 patients with known PD-L1 status, high TMB was associated with a numerically higher odds of response (OR 3.17, 95% CI 0.61–19.57, p = 0.18), and PTEN alterations were still associated with a significantly lower odds of response (OR 0.07, 95% CI 0.003–0.51, p = 0.02) after adjustment for clinical factors and PD-L1.

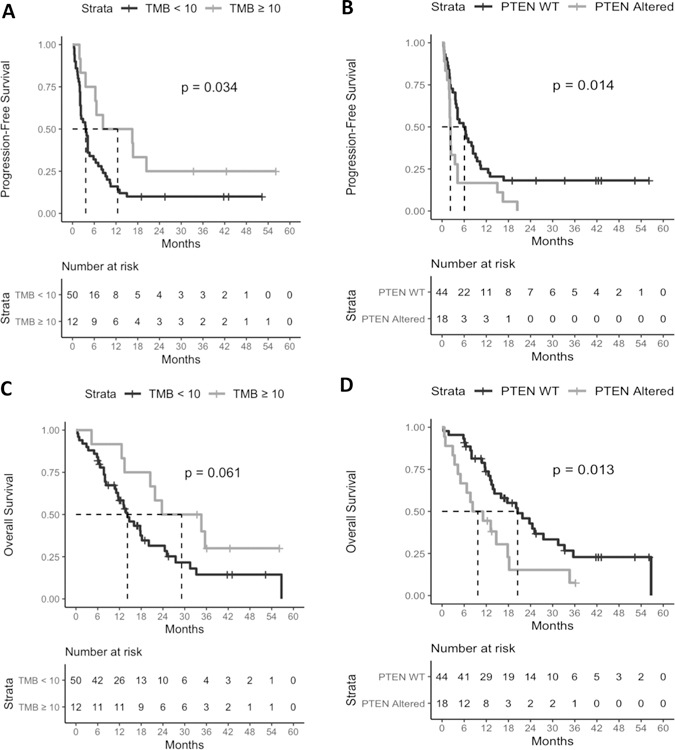

Patients with high TMB experienced longer median PFS (12.5 months, 95% CI 6.3-not reached) versus patients without high TMB (3.7 months, 95% CI 2.3–5.8, log-rank p=0.03; Figure 1A), while patients with PTEN alterations experienced shorter median PFS (2.3 months, 95% CI 2.0–4.2) versus patients without PTEN alterations (6.1 months, 95% CI 3.9–9.1, log-rank p=0.01; Figure 1B). Similarly, patients with high TMB also experienced longer survival (median OS 29.2 months, 95% CI 20.5-not reached) versus patients without high TMB (median OS 14.2 months, 95% CI 11.6–24.5, log-rank p=0.06; Figure 1C), while patients with PTEN alterations experienced shorter survival (median OS 9.7 months, 95% CI 5.0–34.6) versus patients without PTEN alterations (median OS 20.5 months, 95% CI 13.8–33.2, log-rank p=0.01; Figure 1D).

Figure 1. Kaplan-Meier Curves for Progression-Free and Overall Survival by Biomarker Status in Anti-PD-1/L1-Treated Cohort.

(A) Progression-free survival and (C) overall survival by tumor mutational burden status (<10 vs ≥10 mutations/megabase); (B) progression-free survival and (D) overall survival by PTEN alteration (absent vs present). Abbreviations: TMB: tumor mutational burden; WT: wild type.

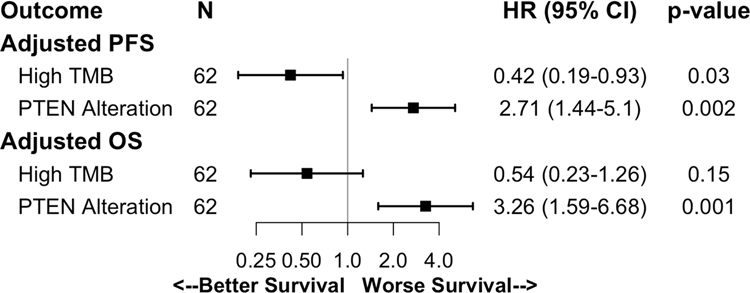

In univariate analyses, patients with high TMB had significantly longer PFS (hazard ratio [HR] 0.46, 95% CI 0.22–0.95, p=0.04) and numerically higher OS (HR 0.48, 95% CI 0.22–1.05, p=0.07) versus those without high TMB, while patients with PTEN alterations had significantly shorter PFS (HR 2.04, 95% CI 1.15–3.63, p=0.01) and significantly worse OS (HR 2.19, 95% CI 1.16–4.13, p=0.02) versus patients without PTEN alterations (Table 2). Multivariate analyses confirmed that patients with high TMB experienced significantly longer PFS (HR 0.42, 95% CI 0.19–0.93, p=0.03) and numerically higher OS (HR 0.54, 95% CI 0.23–1.26, p=0.15), while patients with PTEN alterations had significantly shorter PFS (HR 2.71, 95% CI 1.44–5.10, p=0.002) and OS (HR 3.26, 95% CI 1.59–6.68, p=0.001), independent of clinical factors (Figure 2). In two final multivariate models, the first including both high TMB and PTEN alterations in addition to clinical factors and the second adding PD-L1 status to the first, both high TMB and PTEN alterations remained significantly associated with longer and shorter PFS, respectively, and PTEN alterations remained significantly associated with shorter OS (Table 2). Alterations in other immunotherapy-related pathways did not show statistically significant associations with response (eResults and eTable 2 in the Supplement).

Table 2.

Univariate and multivariate analysis of factors associated with progression-free and overall survival following immune checkpoint-inhibitor-based therapies

| Progression-Free Survival | Overall Survival | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | p-value | HR | 95% CI | p-value | |

|

Univariate Models

(n = 62) | ||||||

| High TMB | 0.46 | 0.22–0.95 | 0.04 | 0.48 | 0.22–1.05 | 0.07 |

| PTEN alteration | 2.04 | 1.15–3.63 | 0.01 | 2.19 | 1.16–4.13 | 0.02 |

| ECOG PS | 1.72 | 0.58–3.05 | 0.06 | 3.24 | 1.74–6.04 | 0.0002 |

| Previous lines of therapy | 1.57 | 0.91–2.71 | 0.11 | 1.39 | 0.75–2.56 | 0.30 |

| Regimen | 1.31 | 0.69–2.49 | 0.41 | 1.14 | 0.57–2.26 | 0.72 |

| Visceral metastases | 1.10 | 0.59–2.06 | 0.77 | 1.11 | 0.56–2.20 | 0.77 |

|

High TMB Multivariate Model

(n = 62) | ||||||

| High TMB | 0.42 | 0.19–0.93 | 0.03 | 0.54 | 0.23–1.26 | 0.15 |

| ECOG PS | 1.64 | 0.89–3.00 | 0.11 | 2.93 | 1.53–5.63 | 0.001 |

| Previous lines of therapy | 1.57 | 0.89–2.76 | 0.12 | 1.29 | 0.68–2.45 | 0.43 |

| Regimen | 1.83 | 0.90–3.73 | 0.10 | 1.54 | 0.71–3.35 | 0.27 |

| Visceral metastases | 1.50 | 0.79–2.86 | 0.22 | 1.35 | 0.65–2.82 | 0.42 |

|

PTEN Alteration Multivariate Model

(n = 62) | ||||||

| PTEN alteration | 2.71 | 1.44–5.10 | 0.002 | 3.26 | 1.59–6.68 | 0.001 |

| ECOG PS | 1.98 | 1.08–3.62 | 0.03 | 3.84 | 1.99–7.39 | 0.00006 |

| Previous lines of therapy | 1.83 | 1.02–3.29 | 0.04 | 1.57 | 0.81–3.06 | 0.18 |

| Regimen | 1.84 | 0.90–3.74 | 0.09 | 1.69 | 0.78–3.62 | 0.18 |

| Visceral metastases | 1.21 | 0.64–2.30 | 0.56 | 1.05 | 0.52–2.14 | 0.88 |

|

High TMB and PTEN Alteration Multivariate Model

(n = 62) | ||||||

| High TMB | 0.37 | 0.17–0.80 | 0.01 | 0.48 | 0.20–1.14 | 0.10 |

| PTEN alteration | 3.07 | 1.62–5.81 | 0.0006 | 3.44 | 1.67–7.07 | 0.0008 |

| ECOG PS | 1.67 | 0.91–3.05 | 0.10 | 3.34 | 1.72–6.49 | 0.0004 |

| Previous lines of therapy | 1.79 | 1.00–3.21 | 0.05 | 1.48 | 0.76–2.87 | 0.25 |

| Regimen | 2.38 | 1.15–4.96 | 0.02 | 2.05 | 0.92–4.55 | 0.08 |

| Visceral metastases | 1.45 | 0.75–2.78 | 0.27 | 1.28 | 0.61–2.67 | 0.52 |

|

High TMB, PTEN Alteration, and PD-L1 Multivariate Model

(n = 37) | ||||||

| High TMB | 0.37 | 0.15–0.91 | 0.03 | 0.42 | 0.16–1.11 | 0.08 |

| PTEN alteration | 2.82 | 1.16–6.85 | 0.02 | 2.93 | 1.14–7.53 | 0.03 |

| PD-L1 | 0.78 | 0.31–1.93 | 0.59 | 1.28 | 0.48–3.43 | 0.63 |

| ECOG PS | 1.16 | 0.47–2.87 | 0.74 | 2.27 | 0.90–5.73 | 0.08 |

| Previous lines of therapy | 1.41 | 0.62–3.18 | 0.41 | 1.39 | 0.59–3.30 | 0.45 |

| Regimen | 1.18 | 0.41–3.42 | 0.76 | 1.70 | 0.58–4.97 | 0.33 |

| Visceral metastases | 0.71 | 0.27–1.88 | 0.50 | 1.00 | 0.39–2.59 | 0.99 |

High TMB: ≥ 10 mutations/megabase vs. < 10 mutations/megabase; PTEN alteration (nonsynonymous mutation or 1 or 2 copy deletion): present vs. absent; PD-L1: positive vs. negative; ECOG PS: ≥ 1 vs. 0; Previous lines of therapy: ≥ 1 vs. 0; Regimen: monotherapy vs. combination therapy; Visceral metastases: present vs. absent.

Abbreviations: CI: confidence interval; ECOG-PS: Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; HR: hazard ratio; TMB: tumor mutational burden.

Figure 2. Adjusted Hazard Ratios (HR) for Progression-Free Survival (PFS) and Overall Survival (OS) by Biomarker Status in Anti-PD-1/L1-Treated Cohort.

PFS and OS HRs by TMB ≥10 vs. <10 mutations/megabase and PTEN alterations (present vs. absent), adjusted for ECOG PS (≥ 1 vs. 0), previous lines of therapy (≥ 1 vs. 0), regimen (monotherapy vs. combination therapy), and visceral metastases (present vs. absent). Abbreviations: ECOG-PS: Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; CI: confidence interval; HR: hazard ratio; TMB: tumor mutational burden.

To explore whether high TMB and PTEN alterations are predictive or prognostic, we examined the association of high TMB and PTEN alterations with PFS and OS in previously published mTNBC cohorts treated with chemotherapy (n = 90) and non-ICI regimens (n = 169, eMethods in the Supplement).27 We analyzed PFS and OS in 90 patients with mTNBC, who underwent pre-treatment targeted DNA sequencing (MSK-IMPACT; 57% with 410-gene version 2 covering 1.016478 Mb of exon) on either a metastatic (62%) or primary (34%) tumor sample and were treated with single-agent chemotherapy (71%) or combination chemotherapy (29%) that was not labeled as neoadjuvant or adjuvant treatment.27 We also analyzed OS in 169 patients with mTNBC treated with regimens that did not include immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs).27 In these cohorts, neither high TMB nor PTEN alterations were associated with PFS and/or OS in univariate or multivariate analyses adjusted for prior lines of metastatic therapy (≥1 versus 0) and chemotherapy regimen (monotherapy vs. combination; eTable 3 and eFigures 3–5 in the Supplement).

Discussion

Prior work has shown that high TMB is associated with higher response rates and prolonged PFS following anti-PD-1/L1 therapy across different tumor types,7, 10, 13–15, 28–32 and that PTEN loss is linked to inferior responses to PD-1 blockade and resistance to T cell-mediated immunotherapy.19, 20 However, the relationship of high TMB and PTEN alterations with immunotherapy response in mTNBC has not previously been well characterized. In this mTNBC cohort with comprehensive clinical and genomic annotations, we observed a significant positive association of high TMB with longer PFS and a significant negative association of PTEN alterations with lower ORR and shorter PFS and OS among patients with mTNBC treated with anti-PD-1/L1 therapies. Importantly, these associations remained significant after adjustment for PD-L1 status and clinical confounders, including monotherapy versus combination regimen and first versus higher treatment line, indicating that these factors are unlikely explanations for the observed associations.

The identification of biomarkers that predict clinical benefit to ICI-based therapies is needed to better select patients who are more likely to benefit from therapy and spare patients less likely to benefit from immunotherapy toxicity. To date, there are only 2 validated and clinically available biomarkers that predict benefit to ICI: mismatch repair deficiency (dMMR)33 and PD-L1 expression.34 Yet dMMR is rare in breast cancer, occurring in < 2% of tumors, more commonly in early stage disease.33 As for PD-L1, the phase III IMpassion130 study showed that the combination of atezolizumab plus nab-paclitaxel was superior to nab-paclitaxel alone only for patients with treatment-naïve mTNBC tumors with ≥ 1% PD-L1-positive immune cells by the SP142 antibody.6 This led to the recent FDA approval for this regimen in PD-L1-positive patients. However, a minority of patients with TNBC have PD-L1-positive tumors by the approved companion diagnostic PD-L1 SP142 assay, ranging from 40% in IMpassion130,6 which included primary and metastatic tumors, to 25% of mTNBC tumors at our institution. Concerns remain regarding the utility of PD-L1 expression as a reliable biomarker, including its dynamic nature with varying expression over time, the discordance among different PD-L1 assays, and the fact that some PD-L1-negative patients respond to ICIs.35

Thus, there is an unmet need to define better biomarkers to predict benefit and resistance to immunotherapy in mTNBC, and high TMB and PTEN alterations are possible candidates. Using publicly available genomic data from 3969 patients with breast cancer from 6 different cohorts, our group previously showed that 5% of breast cancers have high TMB and that metastatic tumors have a greater prevalence of high TMB than primary tumors (8.4% vs 2.9%).36 In addition, that study showed that high TMB tumors had greater immune cytolytic activity,7 as measured by the RNA expression of the CD8-positive T cell effectors GZMA and PRF1, suggesting that these patients are more likely to respond to ICI therapies. Likewise, PTEN loss correlated with decreased T cell infiltration, reduced T cell expansion, and worse response to PD-1 inhibitors in other tumors.19, 20 Thus, there is reason to hypothesize that TMB and PTEN alterations may be correlates of response to ICIs.

This study showed that high TMB was significantly associated with longer PFS independent of clinical factors and PD-L1 status. These results are supported by the TAPUR study, a prospective clinical trial of single-agent pembrolizumab in heavily pre-treated metastatic breast cancer patients with TMB ≥ 9 mutations/Mb, which reported an overall response rate of 21% and a durable clinical benefit rate of 37%.37 In addition, other studies have shown that TMB and PD-L1 expression are independent predictive markers of response to ICI therapies and have low correlation across multiple cancers.16, 17 In fact, higher TMB has been associated with worse response to non-ICI treatments in metastatic breast cancer.38 Samstein et al. similarly showed that there was no association between TMB and OS in a cohort of 860 patients with breast cancer treated with non-ICI therapies,18 which we similarly concluded examining only patients with TNBC from the same institution. The Samstein et al. study also had a small cohort of patients with metastatic breast tumors treated with ICIs (n = 45), including 25 patients with ER-negative tumors, which did not demonstrate an association between high TMB and OS. However, only 4 of the 45 patients included in this cohort had tumors with TMB ≥10 mutations/Mb, 20 patients (45%) received single-agent anti-CTLA-4 therapy, and the clinical outcome data were not directly accessed from structured clinical trials. In contrast, all patients in the present study received anti-PD-1/L1-based regimens on a clinical trial.

This study also demonstrated that PTEN alterations were significantly associated with lower ORR and shorter PFS and OS independent of clinical factors and PD-L1 status. Prior analyses have demonstrated that partial PTEN deletions associate with worse OS in breast cancer.26 These findings highlight the importance of determining whether PTEN alterations are predictive or prognostic and prompted our analyses of PTEN alterations in patients with mTNBC treated with chemotherapy and non-ICI therapies, which, although underpowered, suggested that PTEN alterations are not prognostic. Regardless, the present findings about PTEN alterations underlying ICI resistance are directly applicable to the current clinical development of immunotherapy combinations in mTNBC. Consistent with the finding that PI3K/AKT pathway inhibition reversed resistance to T-cell mediated immunotherapy in murine models19, a phase 1b study of the AKT-inhibitor ipatasertib and (nab)-paclitaxel combined with atezolizumab in 26 patients with mTNBC demonstrated an impressive ORR of 73%, which represents an improvement over doublet regimens of taxane chemotherapy combined with atezolizumab or ipatasertib across biomarker subgroups.39 Several larger trials are currently being developed to further investigate the combination of AKT inhibitors, PD-1/L1 inhibitors, and chemotherapy in patients with mTNBC. Whether future trials confirm that PTEN-altered mTNBC harbors ICI resistance that may be reversed by PI3K/AKT/mTOR inhibitors remains to be determined.

Limitations

This analysis of prospectively treated patients has several limitations, including the small sample size, the heterogeneity of prior and current therapy regimens including monotherapy and combination immunotherapy regimens, and the lack of functional validation that the observed PTEN alterations, which included single copy deletions, led to decreased PTEN expression in tumors. In addition, the prevalence of high TMB in this study was higher than previously reported. Possible explanations include that OncoPanel only evaluates tumor without concurrent germline DNA and that high TMB tumors were assessed with OncoPanel versions covering < 1 Mb of exome, which can overestimate TMB versus whole exome sequencing.32, 40 Moreover, the ideal cutoff for defining high TMB in mTNBC is unknown. We used the same cutoff as reported in the large pan-cancer analysis by Campbell et al.41 Overall, our study alone does not prove that TMB and PTEN alterations are predictive biomarkers. Instead, additional validation studies, including analyses of TMB and PTEN alterations in larger cohorts of immunotherapy and non-immunotherapy treated patients, are required to establish these correlates as predictive biomarkers of response to ICIs in mTNBC.

Conclusion

As the first genomic analysis of anti-PD-1/L1 response in a mTNBC cohort with in-depth clinical annotations, this study found that patients with versus without high TMB were more likely to experience longer PFS and that patients with versus without PTEN alterations were more likely to progress and experience shorter PFS and OS, even after adjustment for clinical heterogeneity and PD-L1 status. Prospective studies are required to validate the associations of high TMB and PTEN alterations with ICI response in mTNBC and to determine whether these findings are generalizable to early stage TNBC. To elucidate the role of high TMB, we designed a currently enrolling multicenter phase II trial of nivolumab plus ipilimumab in metastatic HER2-negative breast cancers with high TMB (NIMBUS, NCT03789110). Similarly, the role of PTEN alterations may be clarified in ongoing clinical trials investigating whether AKT inhibitors reverse resistance to PD-1 blockade.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the NCI Breast Cancer SPORE at DF/HCC #P50CA168504 (N. Wagle, N.U. Lin and E.P. Winer), Breast Cancer Research Foundation (N.U. Lin and E.P. Winer), and Fashion Footwear Association of New York (to Dana-Farber Cancer Institute Breast Oncology Program). Sara Tolaney had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. We kindly thank Kate Bifolck for her editorial support to this work. The authors would also like to acknowledge the DFCI Oncology Data Retrieval System (OncDRS) for the aggregation, management, and delivery of the genomic research data used in this project.

Conflict of interest disclosure statement: R.B-S. has served as an advisor/consultant to Eli Lilly and Roche and has received honoraria from Eli Lilly, Roche, Bristol-Myers Squib, Novartis, Pfizer, and travel, accommodations, or expenses from Roche. DD is on the Advisory Board for Oncology Analytics, Inc, and is a consultant for Novartis. EPW receives consulting fees from InfiniteMD and Leap Therapeutics, honoraria from Genentech, Roche, Tesaro, Lilly, and institutional research funding from Genentech. NUL has received institutional research funding from Genentech, Cascadian Therapeutics, Array Biopharma, Seattle Genetics, Novartis, Merck, and Pfizer and has been a consultant/advisor to Seattle Genetics, Puma, and Daichii Sankyo. NW was previously a stockholder and consultant for Foundation Medicine; has been a consultant/advisor for Novartis and Eli Lilly; and has received sponsored research support from Novartis and Puma Biotechnology. EAM has served on scientific advisory boards for: Amgen, Astra-Zeneca, Celgene, Genentech, Genomic Health, Merck, Peregrine Pharmaceuticals, Sellas and Tapimmune. EMV serves as a consultant/advisor to Tango Therapeutics, Invitae, Genome Medical, and Janssen; holds research support from Novartis and Bristol-Myers Squibb; and holds equity in Syapse, Genome Medical, Tango, and Microsoft Corp. SMT receives institutional research funding from Novartis, Genentech, Eli Lilly, Pfizer, Merck, Exelixis, Eisai, Bristol Meyers Squibb, AstraZeneca, Cyclacel, Immunomedics, Odonate, and Nektar. SMT has served as an advisor/consultant to Novartis, Eli Lilly, Pfizer, Merck, AstraZeneca, Eisai, Puma, Genentech, Immunomedics, Nektar, Tesaro, Paxman, Oncopep, Daiichi-Sankyo, and Nanostring.

References

- 1.Garrido-Castro AC, Lin NU, Polyak K. Insights into Molecular Classifications of Triple-Negative Breast Cancer: Improving Patient Selection for Treatment. Cancer Discov 2019;9:176–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nanda R, Chow LQ, Dees EC, Berger R, Gupta S, Geva R, et al. Pembrolizumab in Patients With Advanced Triple-Negative Breast Cancer: Phase Ib KEYNOTE-012 Study. J Clin Oncol 2016;34:2460–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adams S, Loi S, Toppmeyer D, Cescon DW, De Laurentiis M, Nanda R, et al. Phase 2 study of pembrolizumab as first-line therapy for PD-L1–positive metastatic triple-negative breast cancer (mTNBC): Preliminary data from KEYNOTE-086 cohort B. J Clin Oncol 2017;35:1088–1088. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Adams S, Schmid P, Rugo HS, Winer EP, Loirat D, Awada A, et al. Phase 2 study of pembrolizumab (pembro) monotherapy for previously treated metastatic triple-negative breast cancer (mTNBC): KEYNOTE-086 cohort A. J Clin Oncol 2017;35:Abstr 1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dirix LY, Takacs I, Jerusalem G, Nikolinakos P, Arkenau HT, Forero-Torres A, et al. Avelumab, an anti-PD-L1 antibody, in patients with locally advanced or metastatic breast cancer: a phase 1b JAVELIN Solid Tumor study. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2018;167:671–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schmid P, Adams S, Rugo HS, Schneeweiss A, Barrios CH, Iwata H, et al. Atezolizumab and Nab-Paclitaxel in Advanced Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. N Engl J Med 2018;379:2108–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rooney MS, Shukla SA, Wu CJ, Getz G, Hacohen N. Molecular and genetic properties of tumors associated with local immune cytolytic activity. Cell 2015;160:48–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kreiter S, Vormehr M, van de Roemer N, Diken M, Lower M, Diekmann J, et al. Mutant MHC class II epitopes drive therapeutic immune responses to cancer. Nature 2015;520:692–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.DuPage M, Mazumdar C, Schmidt LM, Cheung AF, Jacks T. Expression of tumour-specific antigens underlies cancer immunoediting. Nature 2012;482:405–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Giannakis M, Mu XJ, Shukla SA, Qian ZR, Cohen O, Nishihara R, et al. Genomic Correlates of Immune-Cell Infiltrates in Colorectal Carcinoma. Cell Rep 2016;17:1206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen DS, Mellman I. Elements of cancer immunity and the cancer-immune set point. Nature 2017;541:321–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schumacher TN, Schreiber RD. Neoantigens in cancer immunotherapy. Science 2015;348:69–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rizvi NA, Hellmann MD, Snyder A, Kvistborg P, Makarov V, Havel JJ, et al. Cancer immunology. Mutational landscape determines sensitivity to PD-1 blockade in non-small cell lung cancer. Science 2015;348:124–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carbone DP, Reck M, Paz-Ares L, Creelan B, Horn L, Steins M, et al. First-Line Nivolumab in Stage IV or Recurrent Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med 2017;376:2415–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hellmann MD, Callahan MK, Awad MM, Calvo E, Ascierto PA, Atmaca A, et al. Tumor Mutational Burden and Efficacy of Nivolumab Monotherapy and in Combination with Ipilimumab in Small-Cell Lung Cancer. Cancer Cell 2018;33:853–61 e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cristescu R, Mogg R, Ayers M, Albright A, Murphy E, Yearley J, et al. Pan-tumor genomic biomarkers for PD-1 checkpoint blockade-based immunotherapy. Science 2018;362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ott PA, Bang YJ, Piha-Paul SA, Razak ARA, Bennouna J, Soria JC, et al. T-Cell-Inflamed Gene-Expression Profile, Programmed Death Ligand 1 Expression, and Tumor Mutational Burden Predict Efficacy in Patients Treated With Pembrolizumab Across 20 Cancers: KEYNOTE-028. J Clin Oncol 2019;37:318–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Samstein RM, Lee CH, Shoushtari AN, Hellmann MD, Shen R, Janjigian YY, et al. Tumor mutational load predicts survival after immunotherapy across multiple cancer types. Nat Genet 2019;51:202–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Peng W, Chen JQ, Liu C, Malu S, Creasy C, Tetzlaff MT, et al. Loss of PTEN Promotes Resistance to T Cell-Mediated Immunotherapy. Cancer Discov 2016;6:202–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.George S, Miao D, Demetri GD, Adeegbe D, Rodig SJ, Shukla S, et al. Loss of PTEN Is Associated with Resistance to Anti-PD-1 Checkpoint Blockade Therapy in Metastatic Uterine Leiomyosarcoma. Immunity 2017;46:197–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cancer Genome Atlas Network. Comprehensive molecular portraits of human breast tumours. Nature 2012;490:61–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hanna GJ, Lizotte P, Cavanaugh M, Kuo FC, Shivdasani P, Frieden A, et al. Frameshift events predict anti-PD-1/L1 response in head and neck cancer. JCI Insight 2018;3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.The AACR Project GENIE Consortium. AACR Project GENIE: Powering Precision Medicine through an International Consortium. Cancer Discov 2017;7:818–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Garcia EP, Minkovsky A, Jia Y, Ducar MD, Shivdasani P, Gong X, et al. Validation of OncoPanel: A Targeted Next-Generation Sequencing Assay for the Detection of Somatic Variants in Cancer. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2017;141:751–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sholl LM, Do K, Shivdasani P, Cerami E, Dubuc AM, Kuo FC, et al. Institutional implementation of clinical tumor profiling on an unselected cancer population. JCI Insight 2016;1:e87062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lebok P, Kopperschmidt V, Kluth M, Hube-Magg C, Ozden C, B T, et al. Partial PTEN deletion is linked to poor prognosis in breast cancer. BMC Cancer 2015;15:963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Razavi P, Chang MT, Xu G, Bandlamudi C, Ross DS, Vasan N, et al. The Genomic Landscape of Endocrine-Resistant Advanced Breast Cancers. Cancer Cell 2018;34:427–38 e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Snyder A, Makarov V, Merghoub T, Yuan J, Zaretsky JM, Desrichard A, et al. Genetic basis for clinical response to CTLA-4 blockade in melanoma. N Engl J Med 2014;371:2189–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Van Allen EM, Miao D, Schilling B, Shukla SA, Blank C, Zimmer L, et al. Genomic correlates of response to CTLA-4 blockade in metastatic melanoma. Science 2015;350:207–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Le DT, Uram JN, Wang H, Bartlett BR, Kemberling H, Eyring AD, et al. PD-1 Blockade in Tumors with Mismatch-Repair Deficiency. N Engl J Med 2015;372:2509–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hellmann MD, Ciuleanu TE, Pluzanski A, Lee JS, Otterson GA, Audigier-Valette C, et al. Nivolumab plus Ipilimumab in Lung Cancer with a High Tumor Mutational Burden. N Engl J Med 2018;378:2093–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Campesato LF, Barroso-Sousa R, Jimenez L, Correa BR, Sabbaga J, Hoff PM, et al. Comprehensive cancer-gene panels can be used to estimate mutational load and predict clinical benefit to PD-1 blockade in clinical practice. Oncotarget 2015;6:34221–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Le DT, Durham JN, Smith KN, Wang H, Bartlett BR, Aulakh LK, et al. Mismatch repair deficiency predicts response of solid tumors to PD-1 blockade. Science 2017;357:409–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Reck M, Rodriguez-Abreu D, Robinson AG, Hui R, Csoszi T, Fulop A, et al. Pembrolizumab versus Chemotherapy for PD-L1-Positive Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med 2016;375:1823–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ribas A, Hu-Lieskovan S. What does PD-L1 positive or negative mean? J Exp Med 2016;213:2835–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Barroso-Sousa R, Jain E, Cohen O, Kim D, Buendia-Buendia J, Winer E, et al. Prevalence and mutational determinants of high tumor mutation burden in breast cancer. Ann Oncol 2020. 10.1016/j.annonc.2019.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 37.Chen R, Zinzani PL, Fanale MA, Armand P, Johnson NA, Brice P, et al. Phase II Study of the Efficacy and Safety of Pembrolizumab for Relapsed/Refractory Classic Hodgkin Lymphoma. J Clin Oncol 2017;35:2125–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Maxwell KN, Soucier-Ernst D, Tahirovic E, Troxel AB, Clark C, Feldman M, et al. Comparative clinical utility of tumor genomic testing and cell-free DNA in metastatic breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2017;164:627–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schmid P, Loirat D, Savas P, Espinosa E, Boni V, Italiano A, et al. Phase 1b study evaluating a triplet combination of ipatasertib, atezolizumab, and paclitaxel or nab-paclitaxel as first-line therapy for locally advanced/metastatic triple-negative breast cancer. Cancer Res 2019;79:Abstract nr CT049. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chalmers ZR, Connelly CF, Fabrizio D, Gay L, Ali SM, Ennis R, et al. Analysis of 100,000 human cancer genomes reveals the landscape of tumor mutational burden. Genome Med 2017;9:34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Campbell BB, Light N, Fabrizio D, Zatzman M, Fuligni F, de Borja R, et al. Comprehensive Analysis of Hypermutation in Human Cancer. Cell 2017;171:1042–56 e10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.