Abstract

Background

Despite multiple federal initiatives and calls to action, nursing literature on the health of sexual and gender minority (SGM) populations remains sparse. Low levels of funding for SGM-focused research may be a factor.

Purpose

To examine the proportion and focus of National Institute of Nursing Research (NINR)-funded projects that address SGM health, the number and type of publications arising from that funding, and the reach of those publications over time.

Methods

NINR-funded grants focused on SGM research and bibliometrics of resultant publications were identified using multiple search strategies in NIH RePORTER and PubMed and Scopus, respectively.

Findings

Since 1987, NINR has funded 25 projects addressing the health of SGM populations. Pre-doctoral fellowship funding resulted in more publications in nursing journals than research grant funding.

Discussion

There are clear differences in patterns of funding for fellowships and research grants with corresponding differences in publications and impact on the nursing literature.

Keywords: nursing research, nursing literature, research funding, LGBT persons, sexual and gender minorities

Sexual and gender minority (SGM) people1 make up nearly 5% of the of the United States (US) adult population (Newport, 2018), and experience numerous physical and mental health disparities (e.g., Alzahrani et al., 2019; Haas et al., 2011; Institute of Medicine, 2011; Ploderl & Tremblay, 2015; Reisner et al., 2016). In 2001, the need to focus on SGM people in the nation’s plan to improve the population’s health and end health disparities was recognized in the lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) companion document to Healthy People 2010 (Gay and Lesbian Medical Association and LGBT Health Experts, 2001). The federal government first included objectives about SGM populations in Healthy People 2020 with the goal of improving the “health, safety, and well-being of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) individuals” (U.S Department of Health and Human Services, n.d.). In 2010, the National Academy of Medicine (formerly the Institute of Medicine [IOM]) was asked to evaluate the state of the science related to SGM health, identify gaps in knowledge, and propose a research agenda. The landmark IOM report (2011) highlighted the lack of research addressing the health of SGM population groups in the context of substantial health disparities affecting these populations.

In 2015, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) established the SGM Research Office (SGMRO) to coordinate activities and encourage health research with SGM populations across NIH’s centers and institutes (Sexual and Gender Minority Research Office 2015). The SGMRO’s research coordinating committee released a strategic plan for fiscal years (FY) 2016–2020 with the goals of expanding knowledge of SGM health through research, removing barriers to research implementation with SGM populations, providing support to researchers conducting work with SGM populations, and evaluating progress toward these goals (Sexual and Gender Minority Research Coordinating Committee 2015). The most recent development to support advancing the state of the science on SGM health was the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities’ formal recognition of SGM people as a health disparity population (Perez-Stabile, 2016).

Evidence suggests scarce nursing research addresses SGM health and health disparities (Eliason, Dibble, & Dejoseph, 2010; Jackman et al., 2019). A recent review found that in the top 20 nursing journals, between 2009 and 2017, 0.19% of research articles addressed SGM health (Jackman, Bosse, Eliason, & Hughes, 2019)—a slight increase from a similar review published in 2010 which found that 0.16% addressed SGM health (Eliason et al., 2010). Apart from research literature, there was some indication of growing interest in SGM health as evidenced by an increase in nonresearch articles—such as theorybased articles, editorials, and position statements about SGM health in the top nursing journals (Jackman et al., 2019). The authors posited that the slow growth of nursing research about SGM health may be due, in part, to low levels of funding for this work.

Prior research has documented that only 0.1% of NIH-funded projects focused on SGM health issues unrelated to HIV/AIDS (Coulter, Kenst, & Bowen, 2014). Nurses, one of the largest health professions in the United States, are at the frontlines of providing care to vulnerable populations (IOM, 2010), including SGMs, and rely on nursing science to deliver comprehensive, evidence-based care. Given the critical role that the National Institute of Nursing Research (NINR) plays in building the science upon which nursing practice is based it is important to understand its funding for SGM research. Therefore, our goals were to (1) determine the number of NINR-funded projects dedicated to increasing understanding of SGM populations’ health, and (2) evaluate the resulting contributions to nursing science through publications about SGM health arising from NINR-funded projects and citations of these publications across time.

Method

Search Strategy

To identify NINR-funded projects focusing on SGM health and resulting publications, we used multiple online search strategies via NIH, PubMed, and Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health Professions (CINAHL) (Table 1).

Table 1 –

Search Strategies

| Method | Approach | Source | Fiscal Years Data Available |

|---|---|---|---|

| Research funding identification | |||

| Keyword search | Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, MSM, WSW, LGBT, GLBT, “sexual and gender minority”, “sexual minority”, and “gender minority” combined using the Boolean operator OR. [Limited to projects funded by the NINR] | NIH RePORTER | 1987–2018 |

| Funding category searches | Searched all projects funded by NINR under category “SGM/LGBT” | NIH RePORTER | 2008–2017 |

| All projects funded by NINR under research, condition, and disease categorization (RDIC) “SGM” | NIH RePORT | 2015–2017 | |

| Publication identification | |||

| Principal investigator reported to NIH | A list of all publications affiliated with the research grants identified in the strategies above was downloaded | NIH RePORTER | 1987–2009 |

| Grant number | Each grant number was individually searched in two databases to identify additional publications | CINAHL Complete, PubMed | 1987–2019 |

CINAHL, Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health Literature; GLBT, gay, lesbian, bisexual, transgender; LGBT, lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender; MSM, men who have sex with men; NINR, National Institute of Nursing Research; RePORT, Research Portfolio Online Reporting Tools (https://report.nih.gov/); RePORTER, Research Portfolio Online Reporting Tools Expenditures and Results (https://projectreporter.nih.gov/); SGM, sexual and gender minority.

To determine the denominator represented by total NINR funding, data about NINR research and training spending by year and by mechanism were retrieved from NIH Funding Facts Query (National Institutes of Health Office of Extramural Research, 2019a). We examined funding by grant mechanism to allow for a more precise evaluation of the proportion of NINR’s budget spent on SGM health research.

Inclusion Criteria

Funded projects and subsequent publications were included if they focused on SGM populations or included SGM participants in the sample. When it was unclear whether projects were specific to SGM populations (e.g., HIV/AIDS-related research), two authors independently reviewed project keywords and study abstracts, and discussed discrepancies until agreement was reached.

Variables

Project and publication results, grant number, principal investigator (PI), number of years of funding, funding by fiscal year, total amount of funding (direct and indirect costs for all grant years), number of publications and journals in which they were published were extracted from NIH RePORTER (v 7.40.0; NIH, 2019a). To determine whether the PI on each grant was a nurse, author credentials were reviewed in publications. When no publications were available, the PI’s discipline was identified using Google search for the PI’s name and the institution associated with the funded grant. Articles affiliated with the identified grants were screened for SGM content independently by the first two authors. Articles that did not address SGM people or their health were excluded.

Bibliometrics is a method used to measure the impact of research, and more recently, research funding (Office of Technology Assessment (OTA), 1986). We used this method to measure the impact of NINR’s SGM-focused research funding by calculating the number of publications arising from funded projects and subsequent citations of publications focused on SGM populations, regardless of journal type. The number of citations by year and the years of first and last citation were identified in Scopus, which has been shown to provide better journal coverage for nursing literature than Web of Science (Powell & Peterson, 2017). One publication ((Stumbo, Wrubel, & Johnson, 2011)) was not found in Scopus, so we obtained citation information for this article from Web of Science.

Findings

The search returned 31 NINR-funded studies, 7 of which were excluded from our analyses because the abstracts did not mention SGM people or health. Six of the excluded studies focused on HIV without mention of SGM people (e.g., heterosexual women’s experiences of stigma relatedto livingwith HIV/AIDS,casemanagement among HIV+ homeless young people, end-of-life care for HIV+ people). Twenty-five grants were included in the final analysis, representing 23 principal investigators (PIs). Just over half (n = 13; 52%) of these were research (R mechanism) grants and the remaining (n = 12; 48%) were individual predoctoral (F31) training grants. All F31s, but only two of R-level grants, were awarded to nurse scientists. More than one-half (12; 58.3%) of the F31s and nearly all (12; 92.3%) of the R-level grants were for projects focused on HIV/AIDS among SGM populations. These included HIV prevention interventions; testing, identifying/increasing access to care for HIV+ individuals; relationships in serodiscordant couples; and pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) uptake.

Publications and Citations

The number of publications varied by research project, ranging from 0 to 22, with a total of 67 publications arising from funded R-level grants. However, only 3% of these were published in nursing journals. Over half (57.6%) of the publications focused on SGM populations. Combined, the SGM-focused publications arising from NINR-funded research grants were cited 480 times, with 96% of the citations arising from publications from two specific grants. Two articles arising from R-level funding were published in nursing journals, but neither of these focused on SGM people or health. A summary of research grant funding, publications, and citations is included in Table 2.

Table 2 –

SGM Grants, Corresponding Publications, and Citations of SGM Publications for NINR Research Grants by Mechanism, 1987–2018 (n = 13)

| Funding | Publications (Pubs) |

Citations of SGM Publications |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Start (FY) | End (FY) | Nurse PI | Total Funding ($ US) | # Pubs | # Pubs in Nursing Journals | # Pubs Focused on SGM | # Citations of SGM Pubs | First Year Cited | Last Year Cited |

| R15 | |||||||||

| 1989 | 1989 | Y | 80,286 | 0 | - | - | - | ||

| R21 | |||||||||

| 2008 | 2012 | N | 896,665 | 12 | 0 | 2 | 14 | 2015 | 2019 |

| 2009 | 2010 | N | 436,121 | 0 | - | - | - | - | - |

| 2014 | 2015 | N | 457,895 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 5 | 2017 | 2018 |

| 2015 | 2016 | N | 450,517 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | ||

| 2016 | 2017 | N | 455,440 | 0 | - | - | - | ||

| R01 | |||||||||

| 2001 | 2008 | N | 2,988,900 | 13 | 1 | 0 | - | ||

| 2006 | 2010 | Y | 1,512,310 | 1 | 1 | 0 | - | ||

| 2007 | 2010 | N | 1,525,705 | 0 | - | - | - | ||

| 2009 | 2011 | N | 1,499,067 | 2 | 0 | 0 | - | ||

| 2013 | 2017 | N | 2,957,355 | 14 | 0 | 14 | 208 | 2014 | 2018 |

| 2016 | 2018 | N | 1,807,430 | 22 | 0 | 19 | 253* | 2009 | 2018 |

| 2017 | 2018† | N | 1,389,904 | 0 | - | - | |||

| Total | 16,457,595 | 67 | 2 | 38 | 480 | ||||

| Percent of total pubs | 3.0% | 57.6% | |||||||

FY, fiscal year; PI, principal investigator.

One publication not available in Scopus, so number of citations retrieved from Web of Science.

Active project.

The majority (n = 10; 83.3%) of the NINR-funded F31 predoctoral fellows published at least one article based on their funded research. Combined, the 10 predoctoral fellows authored 29 related publications, most of which (86.2%) were published in nursing journals. Nearly, twothirds of the articles (62.1%) focused on SGM populations. More than three-quarters of the citations are represented by nine publications from two fellowships that ended in 1991. Fellowship grant funding, publications, and citations are presented in Table 3.

Table 3 –

SGM Grants, Corresponding Publications, and Citations of SGM Publications for NINR F31 Fellowship Funding, 1987–2018 (n = 12)

| Funding | Publications (Pubs) |

Citations of SGM Publications |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Start (FY) | End (FY) | Nurse PI | Total Funding ($ US) | # Pubs | # Pubs in Nursing Journals | # Pubs Focused on SGM | # Citations of SGM Pubs | First Year Cited | Last Year Cited |

| 1987 | 1989 | Y | 33,604 | 0 | - | - | |||

| 1989 | 1991 | Y | 37,800 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 209 | 1994 | 2017 |

| 1990 | 1991 | Y | 25,300 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 102 | 1994 | 2018 |

| 1998 | 1999 | Y | 32,732 | 1 | 1 | 0 | - | ||

| 1999 | 2001 | Y | 74,028 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 | 2006 | 2017 |

| 2001 | 2003 | Y | 64,950 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 7 | 2011 | 2016 |

| 2011 | 2012 | Y | 79,198 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 33 | 2013 | 2018 |

| 2012 | 2014 | Y | 106,414 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 2018 | 2018 |

| 2012 | 2014 | Y | 105,972 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 2017 | 2018 |

| 2014 | 2016 | Y | 77,027 | 7 | 6 | 2 | 8 | 2017 | 2019 |

| 2016 | 2017 | Y | 63,641 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 | 2018 | 2019 |

| 2017 | 2017 | Y | 43,117 | 0 | - | - | - | ||

| Total | 743,783 | 29 | 25 | 18 | 376 | ||||

| Percent of total pubs | 86.2% | 62.1% | |||||||

Population, Foci and Types of Manuscripts

Of the publications resulting from SGM-related work, more than three-quarters (76.8%) focused on sexual minority men (i.e., gay and bisexual men, men who have sex with men). Half (50%) of all publications were HIV-focused including HIV risk, prevention, and disease management; perceptions about HIV/AIDS; treatment/medication adherence; and PrEP. Table 4 shows publication topics by population.

Table 4 –

Foci of Manuscripts on SGM Populations Arising From NINR-Funded Research (N = 56)

| Primary Sample Population | Topic/Type of Manuscript |

N | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Substance Use/Recovery | Health Care Experiences | Physical Health/Disparities | Mental Health/Disparities | HIV-Related* | Other STI Focus | Relationships | Expert Opinion/Interview | Research Methods | ||

| Sexual minority men | 5† | 1‡ | 3‡ | 26§ (n = 4) | 2§ (n = 1) | 3 | 3§ (n = 1) | 43 | ||

| Sexual minority women | 5 | 4 | 1 | 10 | ||||||

| Sexual minority men and women | 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| Transgender people | 1∥ | 1 | 2 | |||||||

| Total | 10 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 27 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 56 |

STI, sexually transmitted infection.

Includes HIV risk, HIV prevention, HIV disease management, perceptions about HIV/AIDS or treatment; treatment/medication adherence; pre-exposure prophylaxis.

Focused on HIV+ sexual minority men.

Focused on Black gay and bisexual men.

Literature review/systematic review.

Focused on transgender women.

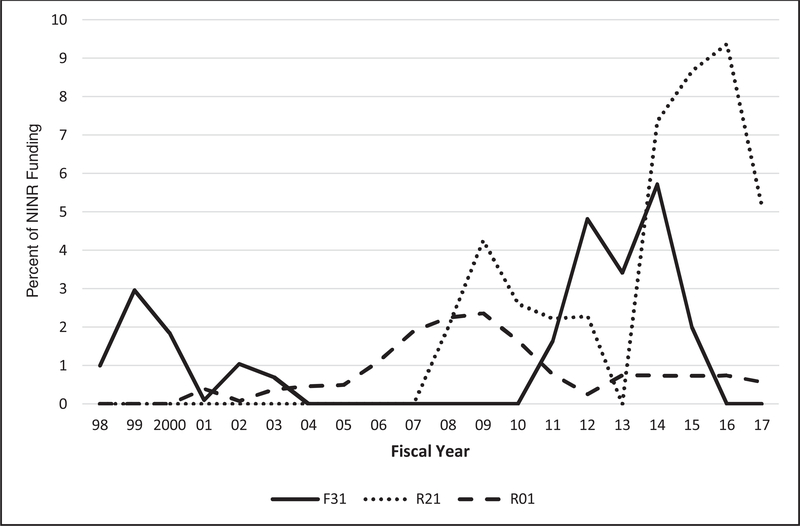

Spending on Research and Training

Funding by mechanism was not available on NIH RePORTER for all years in which funding was awarded. Between 2008 and 2017, the NINR spent $74,425,485 on R21 research, with $687,838 (0.92%) spent on SGM-related research. This represented a range of NINR’s spending on R21s from 0% in 2013 to over 9% in 2016. Similarly, NINR spent $1,415,050,938 in R01-level funding between 1998 and 2015; $12,961,016 (0.92%) of that went to SGM-related research. The proportion of the budget allocated to SGM research varied by year, ranging 0.09% in 2002 to 2.4% in 2009.

Total NINR F31 funding was $40,116,491 between 1998 and 2015, and SGM-focused research during that time accounted for approximately 1.3% ($518,552) of the F31 budget. The proportion of funding for SGM-focused training grants ranged from as low as 0% (2004–2010) to as much as 5.72% (2014). Figure 1 depicts the proportion of the NINR budget spent on SGM research by mechanism and year.

Figure 1–

Percent of NINR funding for SGM research by mechanism and year (FY 1998–2017).

Discussion

This study is the first to examine NINR funding for SGM research by mechanism and to evaluate the impact of this research in resulting publications and citations of these publications. In general, NINR funding for SGM research is low, and there are clear differences in F31-and R-level funding, as well as differences in publication output and impact on the nursing literature. Although the proportion of funding for fellowships is understandably smaller than for research funding, our findings show that fellowship spending led to many more publications in nursing journals, which helps to advance nursing science in the understudied area of SGM health. Two of the NINR-funded fellowships led to the publication of seminal work in the area of sexual minority women’s use of alcohol, which continues to be cited nearly 30 years later. Neither of the publications in nursing journals arising from R-level funding focused on SGM health.

Although the NINR’s mission is not specifically to advance nursing science, all F31 PIs were nurses, whereas only two R mechanism (one R15 and one R01) PIs were nurses. Our findings raise questions about whether nurses who do SGM research are more likely to submit their grant applications to institutes other than NINR, and why researchers from other disciplines choose to submit their applications to the only discipline-specific institute at the NIH. The low number of nurse researchers receiving R-level funding from NINR to do SGM research may help to explain the dearth of SGM research in the nursing literature (Jackman et al., 2019).

Most publications from NINR-funded SGM health grants focused on sexual minority men and HIV. This is in line with findings from other reviews of SGM research funding (Boehmer, 2002; Coulter et al., 2014) as well as NIH’s own evaluations of their research portfolio (SGMRO, 2015; SGMRO 2016, 2017a, 2017b, 2018a). Although HIV has long been associated with sexual minority men, it affects many other populations, as evidenced by the substantial number of grants our search identified in NIH RePORTER that focused on HIV with no reference to SGM people. SGM population groups experience many health disparities unrelated to HIV. The over-focus on sexual minority men and HIV excludes other SGM population groups that also experience substantial health disparities, such as sexual minority women (IOM, 1999) and transgender people (The Lancet, 2016).

Limitations

We recognize that nurse scientist-led projects may be funded by other institutes, that nurse scientists are often part of teams led by researchers from other disciplines, and that grants funded by NINR are not representative of nurses’ contribution to SGM health research. However, our aim was to evaluate NINR funding of SGM health research, not nurse scientists’ contribution to this field. We were unable to determine the number of SGM health focused applications that have been submitted to NINR (or any other NIH Institute). It is possible that fewer SGM focused proposals were received in years that no relevant funding was awarded. It is also possible that a PI or other researcher of an NINR-funded project neglected to include the grant number on resulting manuscripts, which may have resulted in an undercount of publications identified by our methods. Although number of citations is a reasonable measure of impact (OTA, 1986), these often include self-citations, especially for publications arising from multiyear research grants, which could overestimate the reach of the articles. Some citations may have been missed because none of the available bibliometric databases provide complete coverage of journals for citation tracking (Bakkalbasi, Bauer, Glover, & Wang, 2006).

Recommendations

The modest amount of R-level funding related to SGM health may signal to nurse researchers working in this area that NINR is not interested in funding this work. If NINR wishes to alter this potential perception, signing onto existing NIH initiatives that promote SGM health research, such as the recent Notice of Special Interest in Research on the Health of Sexual and Gender Minority (SGM) Populations (NOT-MD-19–001, National Institutes of Health Office of Extramural Research, 2019b) is recommended. Current NINR priorities are broad areas (e.g., symptom science and self-management of chronic conditions) and are relevant to SGM populations. As such, encouraging all researchers who receive funding from NINR to assess SGM identity as common data elements could increase understanding of SGM health and health disparities without additional spending. Researchers should be encouraged to use SGMRO (2018) guidance and resources related to measurement of SGM identity (Sexual and Gender Minority Research Office 2018b). Exploratory research with nurse scientists who conduct SGM-focused research to understand their decision-making processes regarding the submission of grant applications (and subsequent manuscripts for publication) could shed light on common barriers and lead to development of strategies to support SGM-focused research.

The SGM funding category, used as a method of searching NIH RePORTER for grants about the health of these populations, returned several grants that had no relevance to this topic. Clearer definition and operationalization of this funding category would help researchers identify relevant work and enable future evaluation that accurately reflects NIH funding for SGM health.

Conclusion

Although there has been a small increase in NINR funding for SGM research in recent years, the amount of such funding remains low. Most R-level funding for SGM health research has been awarded to non-nurse principal investigators and very few resulting publications appear in nursing journals. In terms of building the evidence base for nursing practice with SGM populations, predoctoral training support has led to important contributions to the nursing literature. Greater funding of nurse scientists’ research related to SGM health has the potential to substantially strengthen nursing’s contribution to reducing health disparities.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

Dr. Jackman is supported by NINR T32NR007969 (PI: Bakken). Dr. Hughes is supported by NIAAA 3R01 AA013328-13.

Footnotes

For the purpose of research at the National Institutes of Health, “SGM populations include, but are not limited to, individuals who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, asexual, transgender, two-spirit, queer, and/or intersex. Individuals with same-sex or -gender attractions or behaviors and those with a difference in sex development are also included. These populations also encompass those who do not self-identify with one of these terms but whose sexual orientation, gender identity or expression, or reproductive development is characterized by non-binary constructs of sexual orientation, gender, and/or sex” (Sexual and Gender Minority Research Office, 2019).

Supplementary materials

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.look.2020.01.002.

REFERENCES

- Alzahrani T, Nguyen T, Ryan A, Dwairy A, McCaffrey J, Yunus R, & Mazhari R (2019). Cardio vascular disease risk factors and myocardial infarction in the transgender population. Circulation, 12 e005597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakkalbasi N, Bauer K, Glover J, & Wang L (2006). Three options for citation tracking: Google Scholar, Scopus and Web of Science. Biomedical Digital Libraries, 3, 7 http://www.bio-diglib.com/content/3/1/7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boehmer U (2002). Twenty years of public health research: Inclusion of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender populations. American Journal of Public Health, 92, 1125–1130. 10.2105/AJPH.92.7.1125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coulter RW, Kenst KS, & Bowen DJ (2014). Research funded by the national institutes of health on the health of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender popu lations. American Journal of Public Health, 104, e105–e112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eliason MJ, Dibble S, & Dejoseph J (2010). Nursing’s silence on lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender issues: The need for emancipatory efforts. Advances in Nursing Science, 33, 206–218. 10.1097/ANS.0b013e3181e63e49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gay and Lesbian Medical Association and LGBT health experts. (2001). Healthy people 2010 companion document for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) health. San Francisco, CA: Gay and Lesbian Medical Association. [Google Scholar]

- Haas AP, Eliason M, Mays VM, Mathy RM, Cochran SD, D’Augelli AR, …, & Clayton PJ (2011). Suicide and suicide risk in lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender populations: Review and recommendations. Journal of Homosexuality, 58, 10–51. 10.1080/00918369.2011.534038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine. (1999). Lesbian health: Current assessment and directions for the future. Washington, DC: National Academies Press. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine. (2010). The future of nursing: Leading change, advancing health. Washington, DC: National Academies Press. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine. (2011). The health of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people: Building a foundation for better understanding. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackman K, Bosse JD, Eliason M, & Hughes T (2019). Sexual and gender minority health in nursing research. Nursing Outlook, 67(1), 21–38, doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2018.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institutes of Health (2019a) Research Portfolio Online Reporting Tools Expenditures and Results (RePORTER) version 7.40.0. Retrieved: https://projectreporter.nih.gov/.

- National Institutes of Health Office of Extramural Research. (2019b). Notice of special interest in research on the health of sexual and gender minority (SGM populations (NOT-MD-19–001). Retrieved from: https://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/notice-files/NOT-MD-19001.html.

- National Institutes of Health Office of Extramural Research. (2019a). Table #106 NIH research grants and other mechanisms including research and development contracts: Number of awards and total funding by NIH institutes/centers and grant mechanism fiscal years 2009–2018. Retrieved from: https://www.report.nih.gov/DisplayRePORT.aspx?rid=569&ver=7.

- Newport F (2018, May 22). In U.S., estimate of LGBT population rises to 4.5% Retrieved from: http://bit.ly/31tLCF8. [Google Scholar]

- Office of Technology Assessment. (1986). Research funding as an investment: Can we measure the returns?: A technical memorandum. Washington, DC: US Congress, Office of Technology Assessment OTA-TM-SET-36. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Stable EJ (2016). Director’s message: Sexual and gender minorities formally designated as a health disparity population for research purposes. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, National Institutes of Health; Retrieved from: http://www.nimhd.nih.gov/about/directors-corner/message.html?utm_mediumemail&utm_source=govdelivery. [Google Scholar]

- Ploderl M, & Tremblay P (2015). Mental health of sexual minorities. A systematic review. International Review of Psychiatry, 27, 367–385. 10.3109/09540261.2015.1083949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell KR, & Peterson SR (2017). Coverage and quality: A comparison of Web of Science and Scopus databases for reporting faculty nursing publication metrics. Nursing Outlook, 65, 572–578. 10.1016/j.outlook.2017.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reisner SL, Poteat T, Keatley J, Cabral M, Mothopeng T, Dunham E, …, & Baral SD (2016). Global health burden and needs of transgender popula tions: A review. The Lancet, 388, 412–436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sexual and Gender Minority Research Coordinating Committee. (2015). NIH FY 2016–2020 strategic plan to advance research on the health and well-being of sexual and gender minorities. Retrieved from: https://www.edi.nih.gov/sites/default/files/EDI_Public_files/sgm-strategic-plan.pdf.

- Sexual and Gender Minority Research Office. (2015). National Institutes of Health FY 2012 sexual and gender minority health research portfolio analysis report. Retrieved from: https://www.edi.nih.gov/sites/default/files/public/EDI_Public_files/downloads/people/lgbti/sgm-research/sgm-nihfy2012-portfolio-analysis-report.pdf.

- Sexual and Gender Minority Research Office. (2016). SGM Portfolio Analysis, FY 2015. Retrieved from: https://dpcpsi.nih.gov/sites/default/files/SGMRO_Portfolio_Analysis_RF5_508.pdf.

- Sexual and Gender Minority Research Office. (2017a). Sexual and gender minority research portfolio analysis: FY 2016. Retrieved from: https://dpcpsi.nih.gov/sites/default/files/SGMRO_2016_Portfolio_Analysis_Final_RF508_508_07192018.pdf.

- Sexual and Gender Minority Research Office (2017b). Sexual and gender minority research office: Annual Report, FY 2016. Retrieved from: https://dpcpsi.nih.gov/sites/default/files/NIH_OD_SGMRO_AnnualReport_RF508_FINAL3_508.pdf.

- Sexual and Gender Minority Research Office (2018a). Sexual and gender minority research office annual report, FY 2017. Retrieved from: https://dpcpsi.nih.gov/sites/default/files/FY2017_SGMRO_AnnualReport_RF508_FINAL_508.pdf.

- Sexual and Gender Minority Research Office (2018b). Methods and measurement in sexual and gender minority health research. Retrieved from: https://dpcpsi.nih.gov/sgmro/measurement.

- Sexual and Gender Minority Research Office (2019). Sexual and gender minority populations in NIH-supported research. Notice number: NOT-OD-19–139: https://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/notice-files/NOT-OD-19-139.html. [Google Scholar]

- Stumbo S, Wrubel J, & Johnson MO (2011). A qualitative study of HIV treatment adherence support from friends and family among same sex male couples. Psychological Education, 2(4), 318–322, doi: 10.4236/psych.2011.24050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Lancet. (2016). Transgender health series. Retrieved from: https://www.thelancet.com/series/transgender-health. Accessed on July 8, 2019.

- U.S Department of Health and Human Services. (n.d.). Office of disease prevention and health promotion. Healthy people 2020. Retrieved from: www.healthypeople.gov.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.