Graphical abstract

Keywords: Cardiac tamponade, COVID-19, Hemorrhagic effusion

Highlights

-

•

There are protean manifestations of cardiac involvement with COVID-19.

-

•

Hemorrhagic pericardial effusion may be the sole cardiac manifestation of COVID-19.

-

•

More work is required to elucidate the mechanism through which COVID-19 causes hemorrhagic pericardial effusion.

Introduction

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is known to affect the heart in multiple ways. Here we present a case of COVID-19 causing hemorrhagic cardiac tamponade in a 62-year-old man who required pericardiocentesis and admission to the intensive care unit.

Case Presentation

A 62-year-old man with multiple comorbidities was brought to the emergency department because of progressive shortness of breath and altered mental status. He had a medical history of coronary artery disease (with drug-eluting stent implantation in the left anterior descending coronary artery 4 years before admission), hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes mellitus, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, alcoholism, and morbid obesity.

In the emergency department, the patient was found to be hypotensive (blood pressure 80/50 mm Hg) and in hypoxic respiratory failure (partial pressure of oxygen 76 mm Hg on arterial blood gas). He was emergently intubated in the emergency department, started on pressors, and transferred to the intensive care unit. Chest radiography revealed bilateral infiltrates with a right pleural effusion (Figure 1). Electrocardiography showed normal sinus rhythm with new low voltage and old left-axis deviation (Figure 2). Laboratory results showed hyponatremia, acute kidney injury, leukocytosis with lymphopenia, mildly macrocytic anemia, coagulation panel within normal limits, elevated d-dimer, and negative serial troponins (Table 1). Echocardiography was emergently done and revealed a large pericardial effusion with tamponade physiology (Figure 3, Video 1). The patient underwent emergent pericardiocentesis from an anterior approach because his obesity precluded the subxiphoid approach. Pericardial pressure was noted to be 35 mm Hg, and 1.1 L of sanguinous fluid was drained. Right heart catheterization was done before and after pericardiocentesis, with pressure measurements detailed in Table 2. Fluid analysis confirmed bloody sanguinous fluid with 1.2 million red blood cells. Cytology revealed peripheral blood components only, with no malignant cells. Initial nasopharyngeal swab for COVID-19 was negative, but subsequent testing from bronchoalveolar lavage sample 2 days later came back positive. Output from the drain decreased and eventually stopped. Repeat echocardiography done 5 days later showed resolution of the pericardial effusion (Figure 4), and the drain was removed. The patient had a prolonged and complicated hospital stay. For COVID-19, he was treated with a course of hydroxychloroquine, ribavirin, and lopinavir-ritonavir combination. He also received steroids and single doses of tocilizumab and anakinra to suppress inflammation. To aid his oxygenation, he was put on inhaled epoprostenol briefly. Although his pressor and inotropic support requirement decreased after pericardiocentesis, he had a component of septic shock from COVID-19 as well and was finally weaned off inotropic and pressor support 10 days after pericardiocentesis. He underwent thoracentesis for the right pleural effusion, which drained 1.6 L of transudative, nonbloody fluid. Bacterial and fungal cultures of pleural fluid were negative. A few complications during his course included renal failure requiring continuous renal replacement therapy for a few days, upper gastrointestinal bleeding that resolved with conservative management, and development of lower extremity deep vein thrombosis. He was finally extubated 18 days after admission and was in the hospital for a total of 28 days. He was followed up in clinic with repeat chest computed tomography still showing ground-glass opacities with residual right pleural effusion (Figure 5).

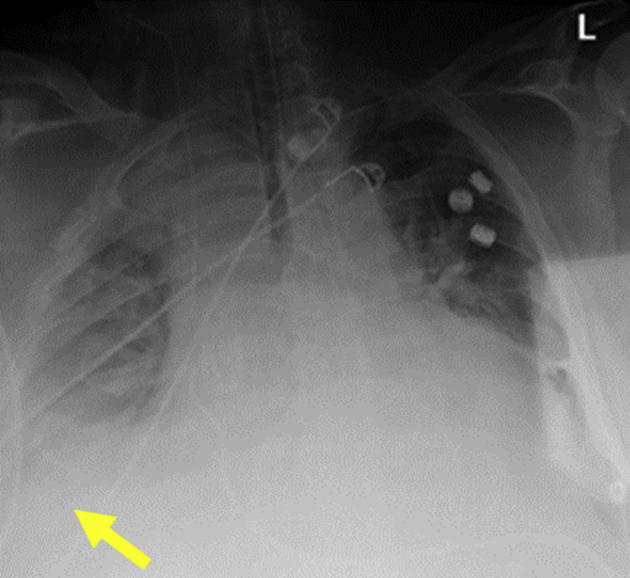

Figure 1.

Chest radiography: a 62-year-old man was brought to the emergency department because of progressive shortness of breath and altered mental status. He was found to be in hypoxic respiratory failure requiring emergent intubation. Chest radiography shows bilateral opacities and right pleural effusion (yellow arrow).

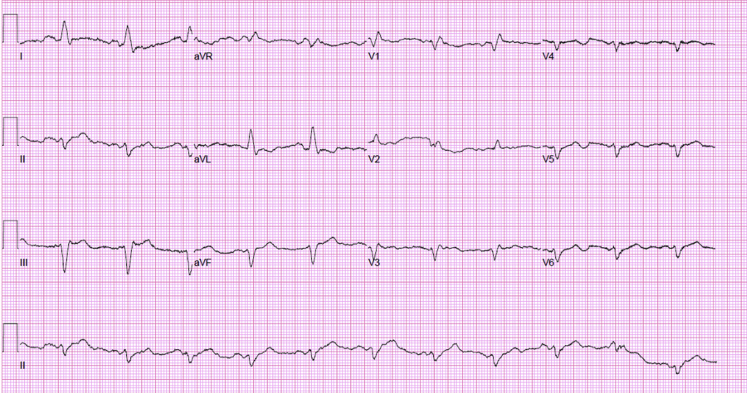

Figure 2.

Electrocardiogram: the patient was in shock and required multiple pressors. Electrocardiography showed normal sinus rhythm, and serial cardiac enzymes were normal.

Table 1.

Basic laboratory findings on admission

| Value | |

|---|---|

| Metabolic panel | |

| Sodium | 125 mEq/L |

| Potassium | 2.6 mEq/L |

| Chloride | 73 mEq/L |

| CO2 | 34 mmol/L |

| Anion gap | 18 mEq/L |

| Blood urea nitrogen | 61 mg/dL |

| Creatinine | 4.7 mg/dL |

| Glucose | 200 mg/dL |

| Calcium | 8.9 mg/dL |

| Liver function tests | |

| Albumin | 3.3 g/dL |

| Total bilirubin | 1.4 mg/dL |

| Direct bilirubin | 0.8 mg/dL |

| Alkaline phosphatase | 86 U/L |

| Alanine transaminase | 7 U/L |

| Aspartate transaminase | 26 U/L |

| Complete blood count | |

| White blood cell count | 14,000/μL |

| Hemoglobin | 11.7 g/dL |

| Mean corpuscular volume | 101.6 fL |

| Platelet count | 390,000/μL |

| Lymphocytes | 7.10% |

| Coagulation parameters | |

| Prothrombin time | 16.3 sec |

| International normalized ratio | 1.3 |

| Partial thromboplastin time | 34.4 sec |

| d-dimer | 2.9 μg/mL |

| Cardiac markers | |

| Troponin (three serial draws) | Negative |

Basic laboratory tests on admission were significant for hyponatremia (hypervolemic hyponatremia from tamponade physiology and acute renal failure), acute kidney injury, leukocytosis with lymphopenia (associated with COVID-19 infection), mildly macrocytic anemia in setting of alcohol use disorder, and coagulation panel within normal range apart from elevated d-dimer (seen in patients with COVID-19); serial troponin draws were negative.

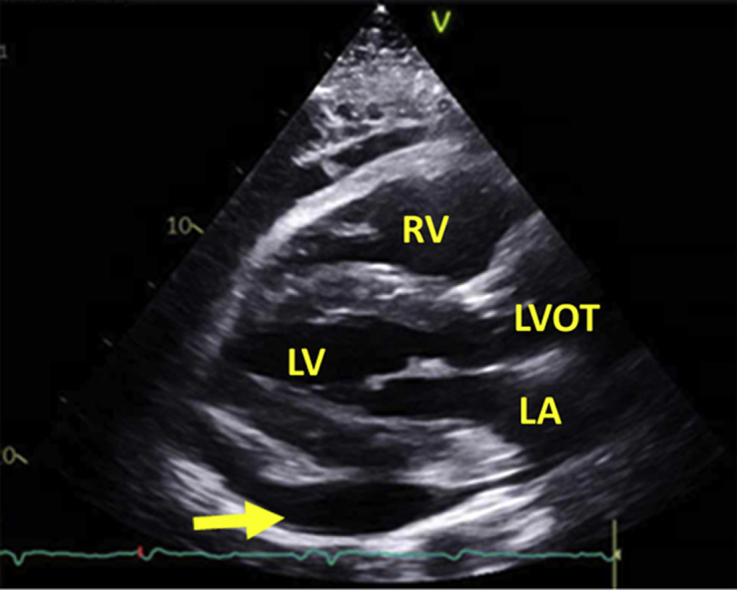

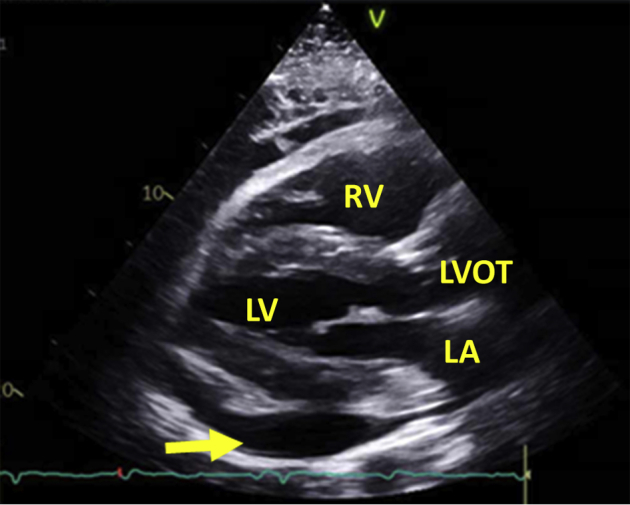

Figure 3.

Echocardiography before pericardiocentesis: transthoracic echocardiography showed pericardial effusion (yellow arrow), with signs of tamponade (not depicted). The patient underwent emergent pericardiocentesis. A total of 1.1 L of sanguinous fluid was drained.

Table 2.

Right heart catheterization pressure measurements before and after pericardiocentesis

| Measurement | Pericardial space (mm Hg) | RA pressure (mm Hg) | RV pressure (mm Hg) | PA pressure (mm Hg) | PCWP (mm Hg) | TPG (mm Hg) | PVR (WU) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before pericardiocentesis (on norepinephrine 14 μg/min and phenylephrine 20 μg/min) | 33–35 | 34 | 62/31 | 67/40/50 | 34 | 16 | 2.8 |

| After pericardiocentesis (on norepinephrine 4 μg/min and phenylephrine 10 μg/min) | 0–5 | 27 | 66/26 | 66/39/49 | 28 | 21 | 3.8 |

PA, Pulmonary artery; PCWP, pulmonary capillary wedge pressure; PVR, pulmonary vascular resistance; RA, right atrial; RV, right ventricular; TPG, transpulmonary gradient; WU, Wood units.

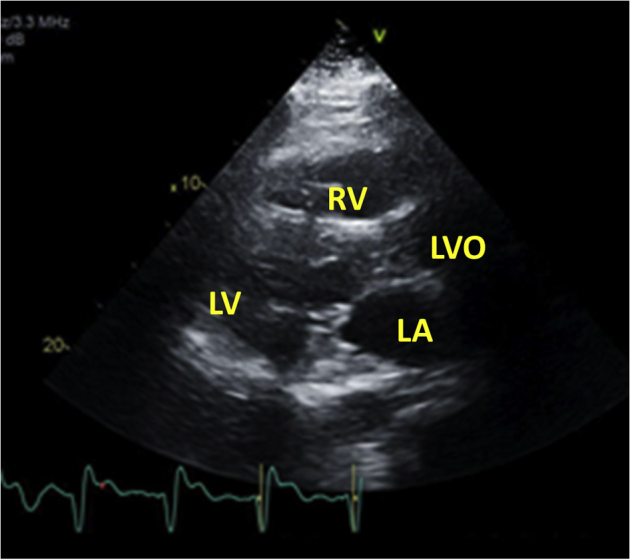

Figure 4.

Echocardiography after pericardiocentesis: drainage from pericardial drain diminished and eventually stopped. Repeat echocardiography 5 days after drain placement showed no residual pericardial effusion.

Figure 5.

Clinic follow-up chest computed tomography showing bilateral ground-glass opacities and small right pleural effusion (yellow arrow).

Discussion

Our patient's presentation with respiratory failure due to COVID-19 pneumonia with concomitant hemorrhagic pericardial effusion not present on recent echocardiography leads us to believe that his pericardial effusion was caused by COVID-19 itself. At this point, our laboratory's COVID-19 polymerase chain reaction assay has not been approved for specimen apart from sputum, nasopharyngeal swabs, or oropharyngeal swabs. Hence we were not able to send the fluid for COVID-19 testing. We did freeze a sample for future testing. However, other common causes of hemorrhagic pericardial effusion were highly unlikely.1,2 Cultures from pericardial fluid showed no evidence of bacterial or fungal infection. Cytology of the pericardial fluid pointed away from malignancy. He had no recent cardiac interventions or trauma that would account for such effusion. Furthermore, his coagulation parameters were within normal limits, ruling out any bleeding diathesis.

This case demonstrates a life-threatening cardiac manifestation of COVID-19. There are currently only two other cases in the English literature of pericardial effusion causing cardiac tamponade in patients with COVID-19.3,4 Of these, only one patient had a hemorrhagic effusion: a 67-year-old woman in Detroit, Michigan, with nonischemic cardiomyopathy (left ventricular ejection fraction 40%) had COVID-19 and was found to have a large hemorrhagic pericardial effusion causing tamponade.3 The other case was from the United Kingdom, where a 47-year-old woman with previous myopericarditis who was COVID-19 positive had cardiac tamponade, and pericardiocentesis drained 540 mL of serosanguinous fluid, which tested negative for COVID.4

Our patient's pleural effusion was transudative and thought to be due to COVID-19 as well. However, we were unable to send the pleural fluid for COVID-19 testing similar to the pericardial fluid. The patient was extubated after 2 days of thoracentesis, and hence the pleural effusion may have had a substantial contribution to his respiratory status.

Although not as common, viral pericarditis can cause hemorrhagic pericardial effusion, especially Coxsackie virus.5, 6, 7 Two possible mechanisms for this phenomenon are direct cytotoxic activity by the virus and immune-mediated pathways.8 Further work as to the pathogenesis of hemorrhagic effusion with COVID-19 will be required.

The interesting point in our case is that the patient had no predisposing risk factors to develop a hemorrhagic effusion. Hence we have a very high clinical suspicion that it was caused by COVID-19.

Conclusion

As we continue to take care of the COVID-19 population, the disease's protean cardiac manifestations will be better understood. It is imperative to note that hemorrhagic pericardial effusion leading to tamponade may be the sole yet potentially lethal manifestation of this viral infection.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: The authors reported no actual or potential conflicts of interest relative to this document.

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.case.2020.05.020.

Supplementary Data

Transthoracic echocardiography showing cardiac tamponade.

References

- 1.Sagristà-Sauleda J., Mercé J., Permanyer-Miralda G., Soler-Soler J. Clinical clues to the causes of large pericardial effusions. Am J Med. 2000;109:95–101. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(00)00459-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Atar S., Chiu J., Forrester J.S., Siegel R.J. Bloody pericardial effusion in patients with cardiac tamponade: is the cause cancerous, tuberculous, or iatrogenic in the 1990s? Chest. 1999;116:1564–1569. doi: 10.1378/chest.116.6.1564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dabbagh M.F., Aurora L., D'Souza P., Weinmann A.J., Bhargava P., Basir M.B. Cardiac tamponade secondary to COVID-19. JACC Case Rep. https://casereports.onlinejacc.org/content/early/2020/05/21/j.jaccas.2020.04.009 Available at: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Hua A., O'Gallagher K., Sado D., Byrne J. Life-threatening cardiac tamponade complicating myo-pericarditis in COVID-19. Eur Heart J. https://academic.oup.com/eurheartj/advance-article/doi/10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa253/5813280 Available at: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Zanini G., Antonioli E., Vizzardi E., Raddino R., Cas L.D. Hemorrhagic pericarditis with cardiac tamponade due to Coxsackie virus infection. Am J Case Rep. 2008;9:60–63. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Spodick D.H., Worcester Bloody pericardial effusion: clinically significant without intrinsic diagnostic specificity. Chest. 1999;116:1506–1507. doi: 10.1378/chest.116.6.1506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hamasaki A., Uchida T., Yamashita A., Akabane K., Sadahiro M. Cardiac tamponade caused by acute coxsackievirus infection related pericarditis complicated by aortic stenosis in a hemodialysis patient: a case report. Surg Case Rep. 2018;4:141. doi: 10.1186/s40792-018-0550-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Adler Y., Charron P., Imazio M., Badano L., Barón-Esquivias G., Bogaert J. 2015 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and management of pericardial diseases: the Task Force for the Diagnosis and Management of Pericardial Diseases of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) endorsed by: the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS) Eur Heart J. 2015;36:2921–2964. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Transthoracic echocardiography showing cardiac tamponade.