Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic and the lockdown and social distancing mandates have disrupted the consumer habits of buying as well as shopping. Consumers are learning to improvise and learn new habits. For example, consumers cannot go to the store, so the store comes to home. While consumers go back to old habits, it is likely that they will be modified by new regulations and procedures in the way consumers shop and buy products and services. New habits will also emerge by technology advances, changing demographics and innovative ways consumers have learned to cope with blurring the work, leisure, and education boundaries.

Keywords: COVID Pandemic, Consumer habits, New regulations for shopping, Customer experience

1. Introduction:

The purpose of this research paper is to examine the impact of Covid-19 pandemic on consumer behavior. Will the consumers permanently change their consumption habits due to lockdown and social distancing or will they go back to their old habits once the global crisis is over? Will there be new habits consumers will acquire due to new regulations related to air travel, shopping at the shopping centers and attending concerts and sports events? Will consumers find that going to a store or attending an event in person is much of a hassle, and therefore, it is better to let the store or the event come to home? To some extent, this has been happening for quite some time in sports tournaments and entertainment by broadcasting them on television and radio.

All consumption is location and time bound. Consumers develop habits over time about what to consume, when and where (Sheth, 2020a, Sheth, 2020b). Of course, this is not limited to consumption. It is also true of shopping, searching for information and post consumption waste disposal. And consumer behavior is highly predictable, and we have many good predictive models and consumer insights based on past repetitive buying behavior at the individual level.

While consumption is habitual it is also contextual. Context matters and there are four major contexts which govern or disrupt consumer habits. The first is change in the social context by such life events as marriage, having children and moving from one city to another. The social context includes workplace, community, neighbors, and friends. The second context is technology. And as breakthrough technologies emerge, they break the old habits. The most dramatic technology breakthroughs in recent years are smart phones, internet and ecommerce. Online search and online ordering have dramatically impacted the way we shop and consumer products and services.

A third context that impacts consumption habits is rules and regulations especially related to public and shared spaces as well as deconsumption of unhealthy products. For example, consumption of smoking, alcohol, and firearms are regulated consumption by location. Of course, public policy can also encourage consumption of societally good products and services such as solar energy, electric cars, and mandatory auto and home insurance services and vaccines for children.

The fourth and less predictable context are the ad hoc natural disasters such as earthquakes, hurricanes, and global pandemics including the Covid-19 pandemic we are experiencing today. Similarly, there are regional conflicts, civil wars as well as truly global wars such as the World War II, cold war, and Great Depression of the late twenties and the Great Recession of 2008–2009. All of them significantly disrupted both consumption as well as production and supply chain. The focus of this paper is to examine both the immediate as well as the long-term impact of Covid-19 on consumption and consumer behavior.

2. Immediate impact on consumer behavior

As mentioned before, all consumption and consumer behavior are anchored to time and location. Since World War II, more and more women have been working resulting in reduction of discretionary time. It is estimated that today more than 75 percent for all women with children at home are working fulltime. This has resulted in time shortage and time shift in family as well as personal consumption. Monday through Fridays, no one is at home between 8am to 5 pm for service technicians to do installations and maintenance of appliances as well as repairs of broken heating and cooling systems. The supplier has to make appointments with the household to ensure there will be someone at home to open the door.

There is also time shortage as the discretionary time of the homemaker is now nondiscretionary due to her employment. This time shortage has resulted in consumers ordering online and have products delivered at home. Similarly, vacations are no longer two or three weeks at a time but are more minivacations organized around major holidays such as Easter, Christmas, Thanksgiving, Memorial Day, and Labor Day extended weekends.

With lockdown and social distancing, consumers’ choice of the place to shop is restricted. This has resulted in location constraint and location shortage. We have mobility shift and mobility shortage. Working, schooling and shopping all have shifted and localized at home. At the same time, there is more time flexibility as consumers do not have to follow schedules planned for going to work or to school or to shop or to consume.

Shortage of space at home is creating new dilemmas and conflicts about who does what in which location space at home. As homo sapiens, we are generally more territorial and each one needs her or his space, we are all struggling with our privacy and convenience in consumption.

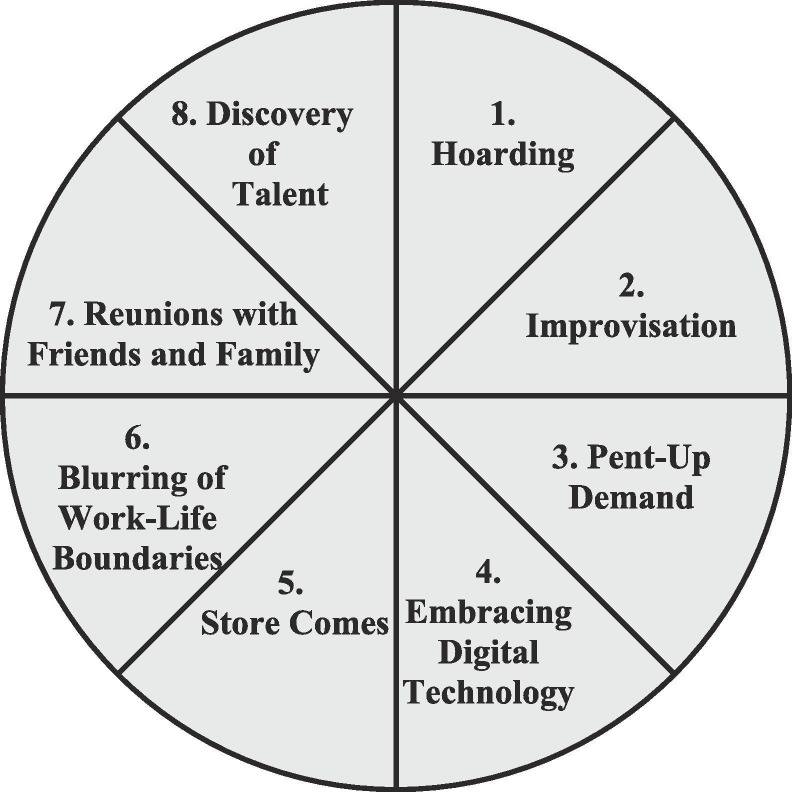

Fig. 1 summarizes eight immediate effects of Covid-19 pandemic on consumption and consumer behavior.

Fig. 1.

Immediate Impact of Covid-19 on Consumption Behavior.

1. Hoarding. Consumers are stockpiling essential products for daily consumption resulting in temporary stockouts and shortages. This includes toilet paper, bread, water, meat, disinfecting and cleaning products.

Hoarding is a common reaction to managing the uncertainty of the future supply of products for basic needs. Hoarding is a common practice when a country goes through hyperinflation as it is happening in Venezuela. In addition to hoarding, there is also emergence of the gray market where unauthorized middlemen hoard the product and increase the prices. This has happened with respect to PPE (personal protection equipment) products for healthcare workers including the N95 masks. Finally, the temporary extra demand created by hoarding, also encourages marketing of counterfeit products. We have not done enough empirical research on the economic and the psychology of hoarding in consumer behavior.

2. Improvisation. Consumers learn to improvise when there are constraints. In the process, existing habits are discarded and new ways to consume are invented. The coronavirus unleashed the creativity and resilience of consumers for such tradition bound activities as weddings and funeral services. Sidewalk weddings and Zoom funeral services substitute for the traditional location centric events. This was also true for church services especially on Easter Sunday.

Improvisation to manage shortage of products or services is another area of future research. It leads to innovative practices and often leads to alternative option to location centric consumption such as telehealth and online education. Once again, there is no systemic empirical or scientific research on improvisation. The closest research is on improvisation is Jugaad in India. It means developing solutions that work by overcoming constraints imposed by social norms or government policy. Jugaad also means doing more with less, seeking opportunity in adversity and thinking and acting flexibly and following the heart (Radjou, Prabhu and Ahujo, 2012).

3. Pent-up Demand. During times of crisis and uncertainty the general tendency is to postpone purchase and consumption of discretionary products or services. Often, this is associated with large ticket durable goods such as automobiles, homes, and appliances. It also includes such discretionary services as concerts, sports, bars, and restaurants. This results in shift of demand from now into the future. Pent up demand is a familiar consequence when access to market is denied for a short period of time for services such as parks and recreation, movies, and entertainment. While economists have studied impact of pent up demand on the GDP growth, there is very little research in consumer behavior about the nature and scope of pent up demand.

4. Embracing Digital Technology. Out of sheer necessity, consumers have adopted several new technologies and their applications. The obvious example is Zoom video services. Just to keep up with family and friends, most households with the internet have learned to participate in Zoom meetings. Of course, it has been extended to remote classes at home for schools and colleges and to telehealth for virtual visits with the physician and other health care providers.

Most consumers like social media including Facebook, WhatsApp, YouTube, WeChat, LinkedIn, and others. The internet is both a rich medium and has global reach. The largest nations in population are no longer China and India. They are Facebook, YouTube, and WhatsApp. Each one has more than a billion subscribers and users. This has dramatically changed the nature and scope of word of mouth advices and recommendations as well as sharing information. One of the fastest growing areas is influencer marketers. Many of them have millions of followers. Impact of digital technology in general and social media in particular on consumer behavior is massive in scale and pervasive in consumer’s daily life. It will be interesting to see if technology adoption will break the old habits. While we have studied diffusion of innovation for telephones, television, and the internet, we have not experienced a global adoption of social media in highly compressed cycle.

5. Store Comes Home. Due to complete lockdown in countries like India, China, Italy, and other nations, consumers are unable to go to the grocery store or the shopping centers. Instead, the store comes home. So does work and education. This reverses the flow for work, education, health and purchasing and consumption. In home delivery of everything including streaming services such as Disney, Netflix, and Amazon Prime is breaking the odd habits of physically going to brick and mortar places. It is also enhancing convenience and personalization in consumer behavior. What we need is to empirically study how “IN-home everything” impacts consumer’s impulse buying and planned vs unplanned consumption.

6. Blurring of Work-Life Boundaries. Consumers are prisoners at home with limited space and too many discrete activities such as working, learning, shopping, and socialization. This is analogous to too many needs and wants with limited resources. Consequently, there is blurring of boundaries between work and home and between tasks and chats. Some sort of schedule and compartmentalization are necessary to make home more efficient and effective.

7. Reunions with Friends and Family. One major impact of the coronavirus is to get in touch with distant friends and family, partly to assure that they are okay but partly to share stories and experience. This resembles high school or college reunions or family weddings. What is ad hoc event to keep in touch is now regular and scheduled get togethers to share information and experiences. Symbolically, we are all sitting on our porch and talking to our neighbors globally. The global reach of the social get togethers through social media such as Zoom and WhatsApp is mind boggling. We need to study sociological and cultural assimilations of consumption practices. Similar to the classic studies such as Reisman et al., 1950, Linder, 1970, Putnam, 2000, we should expect dramatic changes in consumer behavior as a consequence of speedier and universal adoption of new technologies accelerated by the Covid pandemic.

8. Discovery of Talent. With more flexible time at home, consumers have experimented with recipes, practiced their talent and performed creative and new ways to play music, share learning, and shop online more creatively. With some of them going viral, consumers are becoming producers with commercial possibilities. YouTube and its counterparts are full of videos which have the potential for innovation and commercial successes.

3. Will old habits die or return?

It is expected that most habits will return back to normal. However, it is inevitable that some habits will die because the consumer under the lockdown condition has discovered an alternative that is more convenient, affordable, and accessible. Examples include streaming services such as Netflix and Disney. They are likely to switch consumers from going to movie theatres. This is similar to ride sharing services such as Uber which is more user friendly than calling a taxi service. Due to coronavirus, consumers may find it easier to work at home, learn at home and shop at home. In short, what was a peripheral alternative to the existing habit now becomes the core and the existing habit becomes the peripheral.

There is a universal law of consumer behavior. When an existing habit or a necessity is given up, it always comes back as a recreation or a hobby. Examples include hunting, fishing, gardening, baking bread, and cooking. It will be interesting to see what existing habits which are given up by adopting the new ways will come back as hobbies. In other words, will shopping become more an outdoor activity or hobby or recreation?

Modified Habits. In most cases, existing habits of grocery shopping and delivery will be modified by the new guidelines and regulations such as wearing masks and keeping the social distance. This is evident in Asia where consumers wear masks before they go for shopping or use the public transit systems. Modified habits are more likely in the services industries especially in personal services such as beauty parlors, physical therapies, and fitness places. It will also become a reality for attending museums, parks and recreation centers, and concerts and social events, just to name a few.

New Habits. There are three factors which are likely to generate new habits. The first is public policy. Just as we are used to security checks at the airports after 9/11, there will be more screening and boarding procedures including taking the temperature, testing for the presence of the virus and boarding the flight. All major airlines are now putting new procedures for embarking and disembarking passengers as well as meal services. As mentioned before, government policy to discourage or encourage consumption is very important to shape future consumptions.

As mentioned earlier a second major driver of consumer behavior is technology. It has transformed consumer behavior significantly since the Industrial Revolution with the invention of automobiles, appliances, and airplanes. This was followed by the telephone, television, internet and now the social media and the user generated content. The digital technology is making wants into needs. For example, we did not miss the cell phone but today you cannot live without it. Today internet is as important as electricity and more important than television. How technology transforms wants into needs has significant impact on developing new habits such as online shopping, online dating, or online anything. More importantly it has equally significant impact on the family budget between the old necessities (food, shelter, and clothing) in the new necessities (phone, internet, and apps).

The third context which generates new habits is the changing demographics (Sheth and Sisodia, 1999). A few examples will illustrate this. As advanced economies age, new needs for health preservation (wellness) and wealth preservation (retirement) arise. Also, aging population worries about personal safety and the safety of their possessions. Finally, their interest in recreation (both active and passive) changes as compared to the younger population. Similarly, as more women enter the workforce, the family is behaving more like a roommate family. Eating meals together at home every evening is no longer possible. And the dinner together is more of a chore to be completed as fast as possible. Right after the dinner each family member goes to their own private room or space and engage in text messages, YouTube, or watching television. Shared consumption is giving way to individual consumption at the convenience for each family member.

There is also a growing trend of living alone by choice. More than one third of the U.S. households today are single adult households. This is due to delay in first time marriage from age eighteen to age twenty-nine. And with aging of the population, many senior citizens (especially women) are living alone by choice. As a single person household, new habits are formed about what to buy, and how much to buy and from where to buy. In conclusion, changing demographics, public policy and technology are major contextual forces in developing new habits as well as giving up old habits.

4. Managerial implications

There are three managerial implications from the impact of Covid-19 on consumer behavior. First, just as consumers have learned to improvise, business also has to learn to improvise and become more resident during the pandemic crisis. Unfortunately, companies are governed by formal processes and they are often unable to change them quickly. This has been evident in the government’s inability to process the PPP (payroll protection program) loans in the U.S. as well as applying for unemployment benefits.

Fortunately, as more large enterprises have transitioned to cloud computing, it has been easier to improvise. This has been the case with supermarkets and large retailers such as Walmart and Target. The latter, in any case, were converging their brick and mortar stores with their online shopping and even capable of omnichannel delivery. In short, companies can learn how to make their infrastructure, systems and processes to be more resilient; and in the process, manage global crises such as the Covid-19.

A second managerial implication is matching demand and supply. At each retailer ranging from the supermarkets to hyper stores to drug stores, there were chronic shortages due to hoarding and “run on the bank” mentality of consumers in a crisis. Supply chain, logistics, and warehousing operations are critical functions which need to be integrated with the volatile fluctuations in demand. In other words, unlike the current practice of stocking the products on the shelf with a backup inventory in the back of the store, it will be increasingly necessary to encourage online procurement and reverse the process from the merchandise waiting on the shelf for the customer to customer ordering first and the supermarket warehouse assembling the order and delivering it to the customer. As mentioned above, customers coming to the store is not the same as store going to the customer.

A third implication for management is that consumers will go back to their old habits unless the technology they learn to use such as Zoom video services and online ordering brings significant changes in their lives. Customers experience in the virtual world as well as post purchase services (customer support) will be strategic investments.

5. Research implications

As the lockdown and social distancing disrupted the whole range of consumer behavior (ranging from problem recognition to search from information to shopping to delivery to consumption and waste disposal), it has generated several new research opportunities anchored to anchored to the real world. These areas of empirical research with some theoretical propositions on hoarding, blurring the work-life boundaries, use of social media in a crisis are good opportunities to enrich the discipline of consumer behavior.

A social major area for the academic research has to do with consumer resilience and improvisation. It is a new field of research and the Covid-19 crisis has surfaced it as a great research opportunity. For example, are there cultural differences in improvisation across the globe? What are the different techniques used by consumers globally to isolate themselves from the infection?

Finally, Covid-19 has increased the use of social media on Facebook, Instagram, WhatsApp, Twitter, and Zoom. They are generating enormous amount of data on word of mouth. Current analytic techniques are not as useful with video conversations. Just as we developed Natual Language Processing (NLP) to analyze the text data, we will have to develop other techniques to analyze the video content probably anchored to machine learning and artificial intelligence (Sheth, 2020a, Sheth, 2020b). The virtual world is becoming more interesting to consumers compared to the physical world as we have seen in video games and virtual sports. Will artificial become real? For example, is a relationship with a chatbot girlfriend more comfortable and enjoyable as compared to a real girlfriend or boyfriend? In a recent article in Wall Street Journal, Parmy Olson describes several anecdotes of how individuals are interacting with chatbots. According to the author, Microsoft XiaIce social chatbot has more than 660 million users in China alone. In short, the artificial has become real.

6. Conclusion

The lockdown and social distancing to combat the covid-19 virus has generated significant disruptions on consumer behavior. All consumption is time bound and location bound. With time flexibility but location rigidity, consumers have learned to improvise in creative and innovative ways. The work-life boundaries are now blurred as people work at home, study at home, and relax at home. Since the consumer is unable to go to the store, the store has to come to the consumer.

As consumers adapt to the house arrest for a prolonged period of time, they are likely to adopt newer technologies which facilitate work, study and consumption in a more convenient manner. Embracing digital technology is likely to modify existing habits. Finally, public policy will also impose new consumption habits especially in public places such as airports, concerts, and public parks.

Biography

Jagdish N. Sheth is Charles H. Kellstadt Professor of Business in the Goizueta Business School at Emory University. He is globally known for his expertise in consumer behavior, relationship marketing, competitive strategy, and geopolitical analysis. Professor Sheth has over 50 years of combined experience in teaching and research at the University of Southern California, the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Columbia University, MIT, and Emory University. Professor Sheth is the recipient of all four top awards given by the American Marketing Association: the Richard D. Irwin Distinguished Marketing Educator Award, the Charles Coolidge Parlin Award for market research, the P.D. Converse Award for outstanding contributions to theory in marketing, and the William Wilkie Award for marketing for a better society. Professor Sheth is the recipient of an Honorary Doctorate in Science, awarded by the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign (2016), and Honorary Doctorate of Philosophy, awarded by Shiv Nadar University (2017). Professor Sheth has authored or coauthored more than three hundred papers and several books. His latest book is Genes, Climate and Consumption Culture: Connecting the Dots (2017). He is the co-founder, with his wife Madhuri Sheth, of the Sheth Family Foundation, which contributes to many charities both in India and in Atlanta.

References

- Linder Steffan B. Columbia University Press; New York: 1970. The Harried Leisure Class. [Google Scholar]

- Radjou Navi, Prabhu Jaideep, Ahuja Simone. Jossey Bass; London, UK: 2012. Jugaad Innovation: Think Frugal, Be Flexible, Generate Breakthrough Growth. [Google Scholar]

- Reisman David, Nathan Glazer, Denney Reuel. Yale University Press; 1950. The Lonely Crowd: A Study of the Changing American Character. [Google Scholar]

- Putnam Robert D. Simon & Schuster; New York: 2000. Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community. [Google Scholar]

- Sheth Jagdish N. Wiley & Sons; New Delhi, India: 2020. The Howard-Sheth Theory of Buyer Behavior. [Google Scholar]

- Sheth Jagdish N. Next Frontiers of Research in Data Driven Marketing: Will Techniques Keep Up With Data Tsunami? Journal of Business Research. 2020 in press. [Google Scholar]

- Sheth Jagdish, Sisodia R. Revising law like generalizations. Journal of Academy of Marketing Science. 1999;27(Winter):71–87. [Google Scholar]