Abstract

Many have stridently recommended banning markets like the one where coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) originally spread. We highlight that millions of people around the world depend on markets for subsistence and the diverse use of animals globally defies uniform bans. We argue that the immediate and fair priority is critical scrutiny of wildlife trade.

Keywords: animals, disease, pandemic, meat, transmission, wildlife, zoonotic

Novel COVID-19

Classified as a pandemic by the World Health Organization on 11 March 2020, a marketplace in Wuhan, China has been identified as a hotspot for the early spread, and perhaps origin, of COVID-19 [1]. Since the outbreak began in December 2019, the virus has spread to more than 200 countries with global fatalities presently exceeding 367 000 as of 31 May 2020 (https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019). Extreme forecasts predicted that >2.7 million people could die of COVID-19 in the US and UK alone (https://www.imperial.ac.uk/media/imperial-college/medicine/mrc-gida/2020-03-16-COVID19-Report-9.pdf). The restrictive measures implemented to limit disease spread have involved evacuated schools and university campuses, cancelled sporting events and public gatherings, broad-scale travel bans, and stay-at-home ordinances. Byproducts of these measures include widespread unemployment, closure of many small and independent businesses, geopolitical discourse about globalization, and an economic recession sweeping the world almost as swiftly as the disease itself. This calamity leaves the world’s governments and thought leaders searching for answers. Such answers are urgent not only for human health but also for conservation.

Zoonotic Origins of Many Pandemics

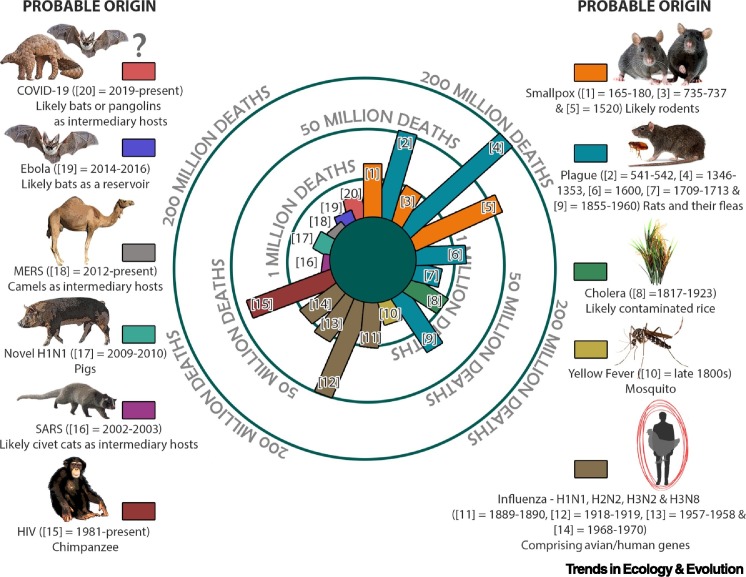

What COVID-19 has made clear is that we have not learned the lessons from past pandemics. Approximately three-quarters of emerging infectious diseases in humans are zoonotic in origin [2]. The COVID-19 outbreak is but one of many pandemics that have been triggered by human–animal interaction (Figure 1 ). The plagues were likely spread by the Yersinia pestis bacterium associated with rats (Rattus spp.) and their fleas [3]. Cohabitation with rats killed hundreds of millions of people in these pandemics (Figure 1). Even more directly, many others have been initiated by the handling or consumption of wildlife as meat or medicament, real or imagined (Figure 1). Such pathways of zoonotic disease transmission have been vociferously highlighted as a prime trigger of pandemics [4].

Figure 1.

The Novel COVID-19 Is among Scores of Pandemics That Have Gripped the World since AD 165.

The number of deaths and probable origins of these diseases are depicted. Abbreviations: COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; MERS, Middle East respiratory syndrome; SARS, severe acute respiratory syndrome.

HIV, for instance, which has killed upwards of 35 million people to date, derived from the butchery of wild chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) as meat [5] (Figure 1). The 2009 novel H1N1 influenza virus, which passed from infected pigs to humans at a meat production facility in Mexico [6], killed a (confirmed) minimum of 18 500 people, with the actual toll likely an order of magnitude, or more, higher [7] (Figure 1). Today, several wild animals are candidates for the reservoir of COVID-19 [8]. Although the source species has yet to be formally identified, bats (Order Chiroptera) and pangolins (Family Manidae) have been implicated as intermediary hosts [9] (Figure 1). Prized for their meat and purported medicinal value, several species of pangolin are now endangered and the marketplaces where they, and countless other species, are traded are prime for zoonotic disease transmission [4]. At one such market in Malaysia, animals were found to be hosts for 19 bacteria, 16 parasites, and 16 viruses that could be passed to people [10]. Thus, even in the absence of pandemics, diseases borne from human–animal interaction in markets can kill people and initiate epidemics [11].

Creating a More Sustainable Future for People and Animals

We recommend that the most immediate and fair priority is critical scrutiny of wildlife trade. First, the criminality of such trade must be taken seriously. Governments, regulators, and wildlife authorities should not tolerate ‘blind eyes’, loopholes, or the negligence of legislation that is now vividly exposed not only to conserve wildlife, but also to save human lives. Furthermore, the contours of illegality should be extended. Currently, wildlife can be legally traded for a variety of consumptive and consumerist purposes at costs, sometimes devastatingly measurable to human health, all too often to animal welfare and conservation, and which COVID-19 reveals now to be extraordinarily high. The use of animals (e.g., consumptive, medicament, pets, or ceremony) however, are so diverse around the world that they defy simple arguments or indiscriminate bans. Within this context, impetuous banning of marketplaces, or other aspects of wildlife trade, could exert profoundly negative and unintended impacts on some of the world’s most vulnerable human populations. Instead, we recommend that societal attention be focused on strengthening, or creating where they do not exist, local authorities responsible for regulating the trade of wildlife for consumption. Furthermore, wildlife can be deeply ingrained in cultural practices, and reactions to COVID-19 should be balanced with respect to the importance of human heritage. What is clear however, is that these dynamics are changing rapidly in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. The unprecedented interconnectedness of global society has now created a new balance of pros and cons. It will take political bravery and a firm grasp of these pros and cons to fortify the regulation of wildlife trade and food supply, along with the realization that the use of animals by communities around the world may need to evolve in line with societal expectations consistent with a new understanding of risk, and indeed restrictions implemented, in the post-COVID-19 world. The prevention of illegal wildlife trade, re-evaluation of certain forms of presently legal wildlife trade, and strengthened food regulatory authorities, including those positioned at marketplaces, are likely among those changes that will need to occur.

COVID-19 has made conspicuous that the costs, in money and suffering both locally and globally, may outweigh the nutritional, cultural, or purported curative benefits of some (perhaps much) wildlife trade, whether illegal or currently legal. There is neither condescension nor conceit in arguing that we all live in one another’s backyard (Box 1 ). As global citizens it is in our shared interest then, to preserve human health and conserve the natural world. The development, wellbeing, and biodiversity of coupled human and natural systems must be adopted as a shared but differentiated global obligation, not least because building the wealth of more economically advantaged countries was associated with extirpation of biodiversity. This realization should only increase the obligation to preserve the rapidly dwindling biodiversity that remains. Therefore, without taking our eyes off the long game (e.g., carbon neutrality, strategic agriculture, reduced meat dependence, and greater appreciation of conservation value), there is an obvious need, and opportunity, for immediate change. Less obvious, but gravely important, is how best to attend to the details of that change, and these details matter greatly. We suggest that a socially just analysis of the diverse risks and ramifications of trade in wildlife, illegal and legal, should be the priority starting point.

Box 1. Interconnectedness of the World.

The COVID-19 pandemic has illustrated the extent to which human communities are linked. Diseases emanating from a single marketplace can spread around the globe in months. Members of both science and society have now stridently called for the outright banning of markets like the one where COVID-19 originally spread. Such calls are understandable, both as humane reactions to the gravity of the COVID-19 pandemic and as tactical efforts to rapidly promote changes that might otherwise take decades to enact. However, in the desire to make the post-COVID-19 world a better one, both for humans and animals, the details matter [12]. We note here that millions of people around the world depend on meat, often wild caught, traded in markets and rural communities for subsistence [13]. Sometimes, unacceptably, people illegally kill threatened species, but more often they harvest wildlife that can be taken both legally and sustainably, where sanctioned harvest systems exist [13]. There are a variety of good reasons to reduce human dependence on all illegally harvested and at least some legally harvested wildlife for subsistence. Importantly however, these are long-term goals requiring fierce attention to the multifaceted and highly variable details inherent to the diverse coupled human and natural systems around the world and feasible only beyond the time-scale affordable for COVID-19 disease control and human health improvement.

Alt-text: Box 1

Acknowledgments

We thank H. Bauer, D. Burnham, P.J. Johnson, E.A. Macdonald, and T. Moorhouse for insightful comments. Thanks to J. Raupp for accuracy and fact-checking support and to A. Stephens, D. Parker, and one anonymous reviewer for editorial comments.

References

- 1.Wu F. A new coronavirus associated with human respiratory disease in China. Nature. 2020;579:265–269. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2008-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Taylor L.H. Risk factors for human disease emergence. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B. 2001;356:983–989. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2001.0888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bramanti B. Yersinia pestis: Retrospective and Perspective. Springer; 2016. Plague: a disease which changed the path of human civilization; pp. 1–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Macdonald D.W., Laurenson M.K. Infectious disease: inextricable linkages between human and ecosystem health. Biol. Cons. 2006;2:143–150. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2006.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Faria N.R. The early spread and epidemic ignition of HIV-1 in human populations. Science. 2014;346:56–61. doi: 10.1126/science.1256739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fraser C. Pandemic potential of a strain of influenza A (H1N1): early findings. Science. 2009;324:1557–1561. doi: 10.1126/science.1176062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dawood F.S. Estimated global mortality associated with the first 12 months of 2009 pandemic influenza A H1N1 virus circulation: a modelling study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2012;12:687–695. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(12)70121-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wan Y. Receptor recognition by the novel coronavirus from Wuhan: an analysis based on decade-long structural studies of SARS coronavirus. J. Virol. 2020;94 doi: 10.1128/JVI.00127-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Andersen K.G. The proximal origin of SARS-CoV-2. Nat. Med. 2020;26:450–452. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0820-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cantlay J.C. A review of zoonotic infection risks associated with the wild meat trade in Malaysia. EcoHealth. 2017;14:361–388. doi: 10.1007/s10393-017-1229-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Daszak P. Emerging infectious diseases of wildlife – threats to biodiversity and human health. Science. 2000;287:443–449. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5452.443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhou Z.-M. China: clamp down on violations of wildlife trade ban. Nature. 2020;578:217. doi: 10.1038/d41586-020-00378-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Montgomery R.A. Poaching is not one big thing. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2020;36:472–475. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2020.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]