Abstract

Residents in long-term care settings are particularly vulnerable to COVID-19 infections and, compared to younger adults, are at higher risk of poor outcomes and death. Given the poor prognosis of resuscitation outcomes for COVID-19 in general, the specter of COVID-19 in long-term care residents should prompt revisiting goals of care. Visitor restriction policies enacted to reduce the risk of transmission of COVID-19 to long-term care residents requires advance care planning discussions to be conducted remotely. A structured approach can help guide discussions regarding the diagnosis, expected course, and care of individuals with COVID-19 in long-term care settings. Information should be shared in a transparent and comprehensive manner to allay the increased anxiety that families may feel during this time. To achieve this, we propose an evidence-based COVID-19 Communication and Care Planning Tool that allows for an informed consent process and shared decision making between the clinician, resident, and their family.

Keywords: Advance care planning, COVID-19, skilled nursing facility, long-term care

Problem

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has a strong influence on the prognosis of individuals living in long-term care (LTC) settings. Recent media reports indicate that at least one-third of COVID-19 deaths are among LTC residents.1 , 2 In the majority of states reporting, at least 50% of deaths are among nursing home and assisted living residents.3 , 4 Frail health combined with communal living conditions, insufficient personal protective equipment, and chronic understaffing are all likely contributing factors to COVID-19 related deaths among LTC residents.

On March 13, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) issued guidance to restrict visitors, including family members, from entering LTC facilities as a means to help reduce the spread of COVID-19 to vulnerable LTC residents.5 Although necessary, this restriction has caused distress. Some families must face the psychological burden of not being able to see and hold their loved ones at the end of life. Further, depriving frail older people of important emotional support and social interactions may contribute to their decline. Further complicating matters is the necessity to use telephones or telemedicine to conduct many advance care planning discussions, rather than through face-to-face interactions. Considering these unique circumstances, we developed a structured approach to support meaningful advance care planning conversations among clinicians, residents, and their families facing COVID-19 infections.

Innovation

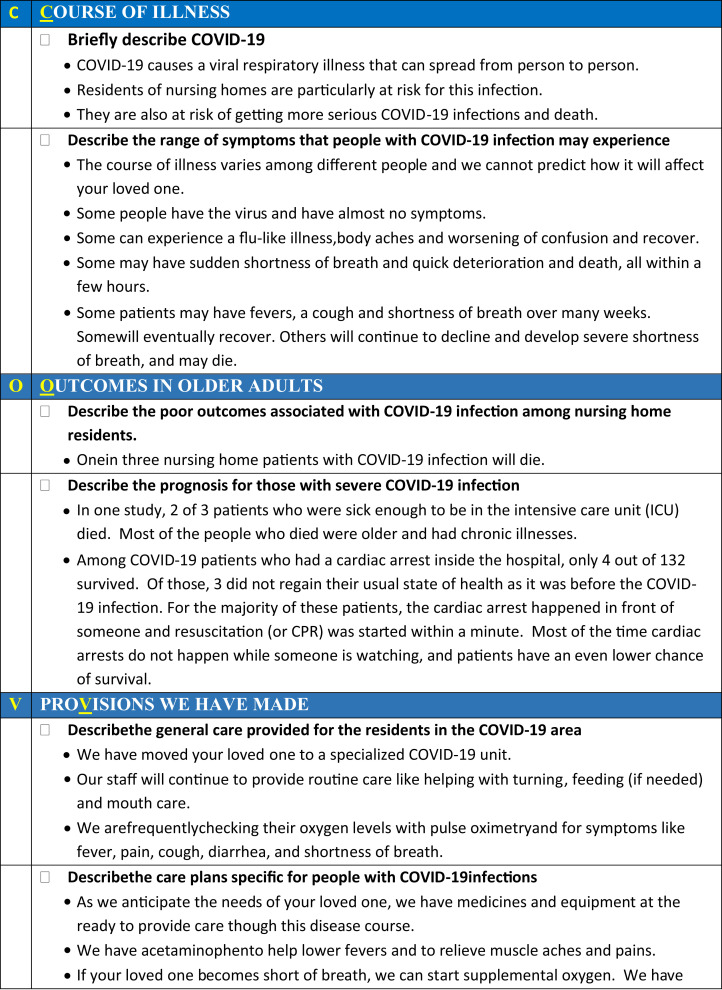

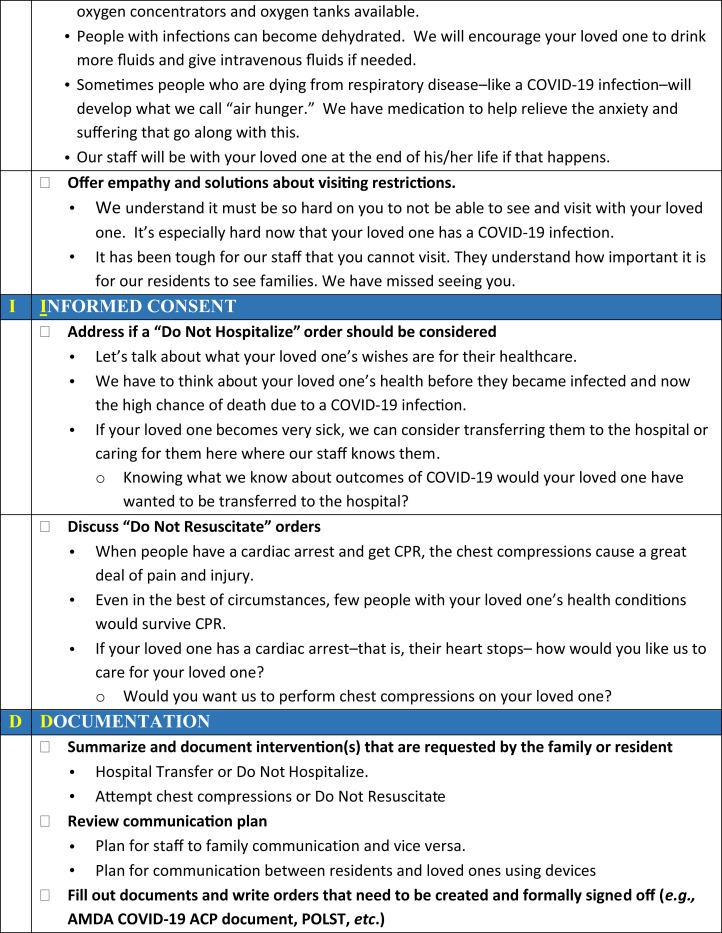

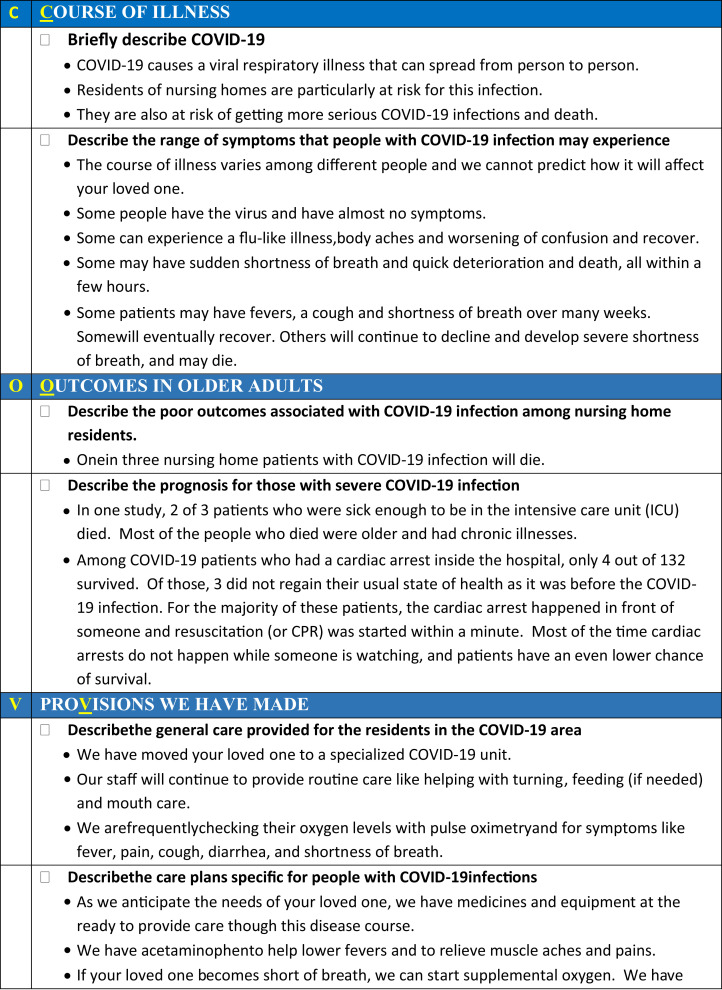

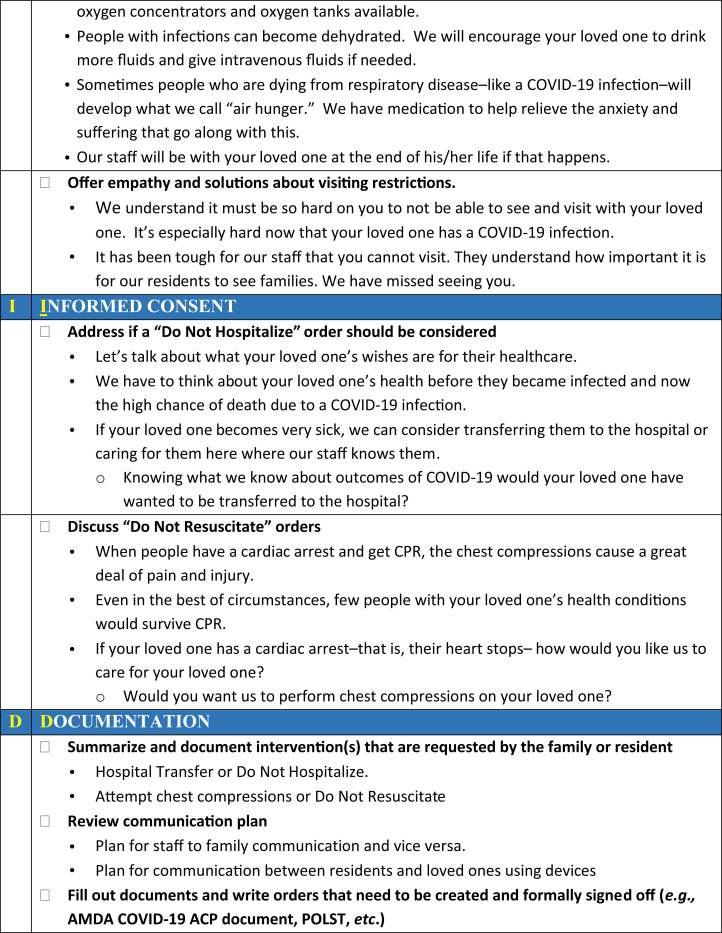

We developed the COVID-19 Communication and Care Planning Tool to provide a structured approach to advance care planning conversations with LTC residents and their families regarding COVID-19 infection and expected outcomes (Figure 1 ). The communication tool is intended to guide staff through conversations specifically around concerns related to COVID-19 infections, a crisis situation considered an important opportunity for advance care planning discussions.6 Although there is no evidence to support any 1 clinical tool for advance care planning,7 the COVID-19 Communication and Care Planning Tool incorporates best practices about discussing serious illness care goals: sharing prognostic information, understanding fears and goals, wishes for family involvement, exploring views on trade-offs and impaired function, and eliciting decision-making preferences.8

Fig. 1.

COVID-19 Communication and Care Planning Tool. This tool is intended to help guide the discussion between a clinician and a resident and/or their family members about COVID-19 infections, including responding to symptoms and to end-of-life considerations. As it is written, the tool is written for a conversation between a clinician and a family member(s). It may be readily adjusted for a conversation with the resident. White squares indicate actions for the clinical staff. Black circles indicate discussion points. The Supplementary Material contains a longer version of this tool in a format that may be modified to suit the needs of individual long-term care settings. A downloadable PDF of this form is available at www.sciencedirect.com.

Using the mnemonic COVID, the communication tool begins by addressing the expected course and outcomes for nursing home residents with COVID-19 infection. Next, the tool indicates what the LTC setting can do to provide for the resident's care and safety. The fourth part, informed consent, acknowledges the anxiety and angst that residents and their loved ones face with this pandemic and then addresses the actions that can be taken. The final element summarizes the decisions made and also reminds staff to complete documentation.

Implementation

A draft of the tool was shared with 10 medical directors with expertise in palliative and end-of-life care; they provided feedback on the content via email with clarifying questions asked during an informal interview process. Following modifications, we distributed the COVID-19 Communication and Care Planning Tool via email to staff physicians, advanced practice professionals (APPs), and nurses. The e-mail included previously described pointers for discussing advance care planning.9

Between April 2 and April 17, 2020, a total of 18 residents at 2 community nursing homes had positive tests for COVID-19; of those, 9 were symptomatic. Staff members (3 physicians, 2 APPs, and 7 nurses) used the COVID-19 Communication and Care Planning Tool as part of the process of notifying residents and family members of test results and accompanying conversations about advance care planning. All conversations took place by telephone or videoconference. Subsequent documentation included a progress note that followed the structure of the communication tool and updates to documentation regarding advance directives, specifying the resident's status regarding do-not-hospitalize and/or do not resuscitate (DNR); a physician reviewed and signed the associated orders.

Following implementation of the tool, we solicited additional feedback from staff members on content, ease of use, including documentation in the electronic medical record, and the approximate times that it took for the informed shared decision-making process. They provided feedback via phone calls and during daily clinical COVID-19 update interdisciplinary conference.

Evaluation

The 10 medical directors provided substantive feedback on the communication tool. First, they indicated that the communication tool contained conversation elements essential to effective advance care planning. Second, incorporating the expected course of COVID-19 infections in older adults provided important context to the families. Third, they noted that focusing on the monitoring and supportive care of individuals with COVID-19 infection in the LTC setting was as essential as discussing interventions of limited or no value, such as transfer to hospital and resuscitation efforts. Finally, the medical directors noted that acknowledging the family's inability to see the resident in person was considered a unique and essential component of advance care planning conversations specific to the risk of COVID-19 infections in LTC facilities.

Among the 18 residents who tested positive, 1 died before their clinicians could schedule a phone call with family members. Among the remaining 17, only 1 (6%) of the residents had a do-not-hospitalize status prior to their diagnosis of COVID-19 infection. Following notifications of positive tests for COVID-19 and use of the communication tool, 9 (52%) of the residents had a do-not-hospitalize status. Regarding DNR, the number of residents with a DNR status rose from 7 (41%) to 15 (88%) following notification of a positive COVID-19 test and use of the communication tool.

Feedback from staff indicated that they valued having comprehensive information to relay to residents and families in a single-page format. The inclusion of outcome evidence was helpful to make decisions. Discussions around resuscitation still proved difficult for a few families, with some staff members requesting more detailed information around resuscitation efforts, specifically intubation. The staff who used the tool reported that average time for completion of discussions was 20 to 25 minutes, with an additional 10 minutes needed for documentation in the medical record.

Comment

The communication tool was well received by the team members who used it, particularly for its focus on the COVID-19 disease and performance as an aid for remote advance care planning discussion. Moreover, the time necessary to hold conversations using this tool was consistent with that expected using the American Medical Association's Advance Care Planning procedural codes (99497-99498).10 The high rates of COVID-19 necessitates a simple albeit comprehensive tool that can be administered by a wide range of HCWs, including physicians, APPs, nurses, and social services where available. To support adoption and sustainability, the Supplementary Material offers a longer, modifiable version of the tool. This version also contains examples of language that users may tailor to suit their LTC settings.

The situation created by the COVID-19 pandemic brings additional challenges to having meaningful discussion about advance care planning. The disease itself is unpredictable, may have a biphasic course, and may occur with few or no warning signs to herald a precipitous decline. Visitation restrictions generate anxiety and grief among family members and prohibit face-to-face conversations with staff. The COVID-19 Communication and Care Planning Tool addresses key elements of the shared decision-making process and also balances challenges specific to COVID-19 infections, such as evolving outcome data and rapidly changing practice patterns resulting from prioritization of strict infection control measures. Future studies will evaluate outcomes including the satisfaction reported by staff, LTC residents, and their family members as they experience advance care planning related to COVID-19 infections.

The pragmatic innovation described in this article may need to be modified for use by others; in addition, strong evidence does not yet exist regarding efficacy or effectiveness. Therefore, successful implementation and outcomes cannot be assured. When necessary, administrative and legal review conducted with due diligence may be appropriate before implementing a pragmatic innovation.

Acknowledgments

N.P. reports support for this work in part through the Nova Southeastern University (NSU) South Florida Geriatrics Workforce Enhancement Program (GWEP), funded by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA). R.L.P.J. reports support for this work in part through the Cleveland Geriatric Research Education and Clinical Center (GRECC) at the VA Northeast Ohio Healthcare System. The contents do not represent the views of NSU, HRSA, the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States Government.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: R.L.P.J. discloses research funding from Pfizer and Merck; she has served on advisory boards for Pfizer and Roche. G.D. discloses serving on an advisory board for Roche. The remaining authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Supplementary data related to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2020.05.062.

Supplementary Data

References

- 1.Yourish K., Lai K.K.R., Ivory D., Smith M. One-third of all U.S. coronavirus deaths are nursing home residents or workers. New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/05/09/us/coronavirus-cases-nursing-homes-us.html Available at:

- 2.For most states, at least a third of COVID-19 deaths are in long-term care facilities. NPR.org. https://www.npr.org/sections/coronavirus-live-updates/2020/05/09/853182496/for-most-states-at-least-a-third-of-covid-19-deaths-are-in-long-term-care-facili Available at:

- 3.Girvan G. 42% of COVID deaths are in nursing homes or assisted living facilities. Medium. 2020. https://freopp.org/the-covid-19-nursing-home-crisis-by-the-numbers-3a47433c3f70 Available at:

- 4.Roy A. 43% of COVID-19 deaths are in nursing homes & assisted living facilities housing 0.6% of U.S. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/theapothecary/2020/05/26/nursing-homes-assisted-living-facilities-0-6-of-the-u-s-population-43-of-u-s-covid-19-deaths/ Available at:

- 5.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Guidance for Infection Control and Prevention of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) in nursing homes (REVISED) | CMS. https://www.cms.gov/medicareprovider-enrollment-and-certificationsurveycertificationgeninfopolicy-and/guidance-infection-control-and-prevention-coronavirus-disease-2019-covid-19-nursing-homes-revised Available at:

- 6.Ampe S., Sevenants A., Coppens E. Study protocol for “we DECide”: Implementation of advance care planning for nursing home residents with dementia. J Adv Nurs. 2015;71:1156–1168. doi: 10.1111/jan.12601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Myers J., Cosby R., Gzik D. Provider tools for advance care planning and goals of care discussions: A systematic review. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2018;35:1123–1132. doi: 10.1177/1049909118760303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bernacki R.E., Block S.D. Communication about serious illness care goals: A review and synthesis of best practices. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174:1994–2003. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.5271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goossens B., Sevenants A., Declercq A., Van Audenhove C. “We DECide optimized”—Training nursing home staff in shared decision-making skills for advance care planning conversations in dementia care: Protocol of a pretest-posttest cluster randomized trial. BMC Geriatr. 2019;19:33. doi: 10.1186/s12877-019-1044-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Medicare Learning Network Advance care planning. 2019. https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=1&cad=rja&uact=8&ved=2ahUKEwiJu52KlvjoAhWkmHIEHcLdDd8QFjAAegQIARAB&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.cms.gov%2Foutreach-and-education%2Fmedicare-learning-network-mln%2Fmlnproducts%2Fdownloads%2Fadvancecareplanning.pdf&usg=AOvVaw2yw_hTfd1EF49EAVY3SNLx Available at:

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.