Abstract

Objective: The present study determines whether Cav-1 modulates the initiation, development and maintenance of type-2 DNP via the Rac1/NOX2-NR2B signaling pathway. Methods: After regular feeding for three days, these rats were randomly divided into two groups: control group with normal-diet (maintenance feed) (n=8); type-2 DM group (n=8). In the type-2 DM group, the rats were fed with a high-fat and high-sugar diet, and received a single intraperitoneal streptozotocin (STZ) injection (35 mg/kg). At two weeks after STZ injection, these diabetic neuropathic pain (DNP) rats were treated with daidzein (0.4 mg/kg/day) and N-tert-Butyl-α-phenylnitrone (PBN, 100 mg/kg/day) for 14 days. After the type-2 DNP model was successfully established, the rats were assigned into four groups: DNP group, DNP+Da group (DNP rats with Cav-1 specific inhibitor daidzein), DNP+PBN group (DNP rats treated with ROS scavenger PBN), and SC group (solvent control group). Then, the mechanical and thermal hyperalgesia were assayed to evaluate the function of the caveolin 1-Recombinant Human Ras-Related C1/nicotinamide adenosine diphosphate oxidase 2-NR2B gene (Cav-1-Rac1/NOX2-NR2B) signaling pathway. In the mechanism study, the protein expression levels of p-Caveolin-1, Rac1, NOX2, p-NR2B and t-NR2B, the production of ROS, and the distribution of Cav-1 and NOX2 in the spinal cord were observed. Results: The present study revealed that p-Cav-1 was persistently upregulated and activated in the spinal cord microglia in type-2 DNP rats. The use of the pharmacological inhibitor of Cav-1 and a ROS scavenger resulted to a significantly relieved mechanical allodynia and thermal hyperalgesia. In addition, it was demonstrated that Cav-1 promoted ROS generation via the activation of Rac1-dependent NADPH oxidase (NOX). Conclusion: The present data suggests that Cav-1 in the spinal cord modulates type-2 DNP via regulating the Rac1/NOX2-NR2B pathway.

Keywords: Type 2 diabetic neuropathic pain, spinal cord, Caveolin-1, NMDA receptor 2B subunit, ROS, NADPH oxidase, central sensitization

Introduction

More than 425 million adults suffer from diabetes worldwide, and approximately 90% of diabetic patients have type-2 diabetes mellitus (DM) [1]. A common and distressing complication of type-2 DM is diabetic neuropathic pain (DNP). DNP is a clinical symptom that manifests as spontaneous pain, paresthesia, dysethesia, hyperalgesia and allodynia [2]. Although this has been extensively studied, the mechanism that underlies DNP remains largely unknown.

Caveolin-1 (Cav-1) is a scaffolding/regulatory protein of specific lipids, and has been identified as the major defining marker of caveolae [3]. Cav-1 is primarily expressed in endothelial cells and fibroblasts, and serves as microdomains for the sequestration of signaling proteins, including receptors and non-receptor tyrosine kinases, endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS), and small GTPases [4]. A recent study revealed that Cav-1 knockout mice exhibited neurologic abnormalities, including abnormal spinning, reduced activity and gait abnormalities [5]. This suggests that Cav-1 is involved in motor control in neurodegenerative diseases. It has been well-established that persistent pain, including neuropathic and inflammatory pain, is associated with the level of reactive oxygen species (ROS) [6,7]. Furthermore, the systemic or intrathecal administration of ROS scavengers and antioxidants inhibit the pain behavior in various animal models of neuropathic pain [8]. In addition, several recent studies have revealed that Cav-1 is positively correlated with ROS [9].

However, it remains unknown whether Cav-1 regulates the ROS level in the spinal cord, and whether such regulation is critical for type-2 DNP. Furthermore, the mechanisms underlying the increased production of ROS in DNP remains poorly defined. Recent studies suggest that NADPH oxidase (NOX) can generate ROS in various diseases and during pain sensitization [10]. NOX2 (which is also known as gp91phox) activity is controlled by regulatory cytosolic subunits p40phox, p47phox and p67phox, and the small GTPase Rac1 [11]. In addition, ROS are involved in NMDA-receptor activation, an essential step in central sensitization, and thus contribute to neuropathic and capsaicin-induced pain [6]. It has been well-accepted that NMDA receptors are involved in central sensitization, and the systemic treatment of phenyl-N-t-butyl nitrone (PBN) eliminated the hyperalgesia and enhanced the phosphorylated NR2B (p-NR2B) expression, which rapidly returned to normal levels [6,12]. Reduction of ROS by PBN prevented enhanced phosphorylation of NR2B subunits. However, it remains unknown whether the contribution of ROS in type-2 DNP is due to the enhanced p-NR2B expression.

The main purpose of the present study is to determine whether Cav-1 modulates the NOX2 activation and the concomitant ROS production, which subsequently leads to the activation of the NMDA receptor and chronic neuropathic pain in a rat model of type-2 DM. These present findings further support the idea that Cav-1 participates in type-2 DNP through NOX2-drived ROS, ultimately modulating the activation of the NMDA receptor.

Materials and methods

Animals

The male, six-week-old Sprague-Dawley rats (130-150 g) were provided by the Center of Laboratory Animal Science of Wenzhou Medical University. All animals were group-housed under a 12-hou light/dark cycle at room temperature (23-25°C), with free access to food and water ad libitum. The procedures were approved by the Animal Use Committee of Wenzhou Medical University, and the IASP’s ethical guidelines for pain research in animals were followed.

The type-2 DNP model and animal groups

The rat model of DNP was fed with a high-fat and high-sugar diet, and received a single intraperitoneal streptozocin (STZ) injection (35 mg/kg). The type-2 DNP model was established, as previously described [13]. After regular feeding for three days, these rats were randomly divided into two groups: control group (n=8), with normal-diet; type-2 DM group, (n=8), with high-sugar and high-fat diet to induce insulin resistance. Rats in the type-2 DM group were intraperitoneally injected with a single 35-mg/kg dose of freshly prepared streptozocin (STZ; St. Louis, MO, USA). The STZ was dissolved in 0.1 M of citrate buffer (pH 4.2). The control group rats received equal volumes of 0.1 M of citrate buffer (pH 4.2). At three days after the STZ injection, the fasting glucose levels were measured from the obtained tail vein blood samples. Rats with glucose level of 16.7 mmol/L or higher were considered diabetic, and were selected for the experiments. Diabetic rats with neuropathic pain were defined as both a mechanical withdrawal threshold (MWT) and thermal withdrawal latency (TWL) of ≤85% of the base value.

After the type-2 DNP model was successfully established, the rats were assigned into four groups: DNP group, DNP+Da group (DNP rats with Cav-1 specific inhibitor daidzein), DNP+PBN group (DNP rats treated with ROS scavenger PBN), and SC group (solvent control group). For these type-2 DM rats, neither TWL, nor MWT >85% of the base value was defined as the PL group. Each group contained eight animals. The daidzein and PBN treatments was 14 days.

Determination of insulin and calculation of the insulin sensitivity index by ELISA

After overnight fasting with free access to water, 0.75 ml of tail vein blood sample was obtained. The rat insulin levels were measured by sandwich ELISA (Haixi Tang Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China). The insulin sensitivity index was calculated using the following formula: 1/(fasting glucose × fasting insulin) [13].

Behavioral tests

MWT was measured for mechanical allodynia, while TWL was detected for thermal hyperalgesia. Before the tests, rats were taken to the room for 30 minutes to adapt to the environment. Then, the WMT and TWL were measured at one day before model establishment, and at 14, 17, 21 and 28 days after STZ injection.

For the MWT, rats were placed into wire-mesh-bottom cages (22 × 22 × 22 cm) and allowed to acclimate for 30 minutes. Then, the plantar surface of the hind paw was stimulated using the IITC 2390 series electronic von Frey tactile pain measurement instrument (Woodland Hills, CA, USA). The maximum force was measured at which the rat lifted its hind paw. Each rat was subjected to six repetitions at 10-minute intervals, and the average was used as the MWT.

For the TWL, rats were placed in a transparent, square plexiglass box (3 mm in thickness, 20 × 15 × 30 cm) and allowed to adapt for up to 30 minutes. Then, the center of the hind paw was exposed to heat stimulation, which was set in the IITC 336 plantar/tail flick tester (Woodland Hills, CA, USA). The reaction time of the animals started from the beginning of the radiant heat measurement until the time the rat shrank away, licked the foot, or squeaked, and this was recorded as the TWL. Each rat was subjected to six repetitions at 10-minute intervals, and the average was used as the TWL [13].

Application of drugs

The daidzein and PBN were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). The daidzein was dissolved in 10% DMSO, while the PBN was dissolved in saline. Then, the daidzein was subcutaneously administrated at a concentration of 0.4 mg/kg, while the PBN was intraperitoneally injected at a concentration of 100 mg/kg. The same volume of 10% DMSO or saline, without any drugs, was injected to rats in the SC group [6,14].

Western blot analysis

Rats were immediately anesthetized after the behavior tests. The spinal lumbar enlargement segments were promptly removed, and rapidly frozen and stored in liquid nitrogen. Then, the samples were weighed and homogenized by mechanical disruption in lysis buffer, containing RIPA, PMSF and protein phosphatase inhibitors. After the homogenates were placed on ice for 30 minutes and centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 25 minutes at 4°C, the supernatant was collected. Then, the protein concentration was measured using a BCA assay kit (Thermo, Rockford, USA). Afterwards, the extracted proteins (30 μg) were diluted with a loading buffer and boiled at 95°C for 10 minutes, and separated by 11% SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Next, these proteins were transferred onto a polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membrane. Then, the membrane was blocked with 10% nonfat dry milk in Tween-20/Tris-buffered saline (TBST) for two hours at room temperature, and subsequently incubated overnight at 4°C with the following primary antibodies: mouse monoclonal anti-Rac1 (1:1,000, ab33186; Abcam Inc., MA, USA), rabbit polyclonal anti-NOX2/gp91phox (1:1,000, ab80508; Abcam Inc., MA, USA), rabbit polyclonal anti-cav-1 (1:3,000, SC-894; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), mouse monoclonal anti-phosphorylated-caveolin-1 (p-cav-1) (1:200, SC-373837; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), mouse monoclonal anti-β-actin (1:4,000, TA-09; Beijing Zhongshan Jinqiao Biotechnology), rabbit polyclonal anti-p-NR2B (1:500, Millipore), and rabbit polyclonal anti-NR2B (1:1,000, ab65783; Abcam). Afterwards, the membranes were washed with TBST for three times for 10 minutes each, and incubated with the secondary antibody (goat anti-mouse IgG or goat anti-rabbit IgG, 1:3,000; Biosharp) for two hours at room temperature. Finally, the labeled proteins were detected by enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL; Thermo Fisher Scientific). The gray values of the target protein bands were quantitatively analyzed using ImageJ software, and normalized against the intensity of the loading control β-actin. The Western blot and IHC method used the same animal.

Double-labeled immunofluorescence

Rats were perfused with 150 ml of saline, followed by 200 ml of 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) diluted in 0.1 M of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Then, the spinal lumbar enlargement segments were dissected and post-fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 12 hours, and dehydrated in 30% sucrose for three days at 4°C. Next, the transverse spinal sections were cut at a thickness of 6 μm. The sections were washed three times for 10 minutes in PBS, and subsequently treated with 0.2% Triton X-100 in PBS for 30 minutes at room temperature. After blocking the nonspecific staining with QuickBlockTM Blocking Buffer for Immunol Staining (Beyotime, P0260), the sections were incubated with mouse anti-gp91phox (1:100, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, SC-130548), rabbit anti-cav-1 (1:200, SC-894; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), mouse anti-NeuN (1:200, MAB377; Millipore), mouse anti-GFAP (1:200, SC-33637; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), mouse anti-CD11b/c[OX42] (1:200, ab1211; Abcam), rabbit anti-NeuN (1:200, ab177487; Abcam), rabbit anti-GFAP (1:200, ab33922; Abcam), and rabbit anti-IBA1 (1:50, 1904-1-AP; Proteintech) overnight at 4°C. Then, the slides were covered with the secondary antibodies (donkey anti-rabbit IgG or donkey anti-mouse IgG, 1:100; Biosharp) containing DAPI (Abcam, UK) for one hour at 37°C. Afterwards, the fluorescently stained sections were examined using a fluorescence microscope (Leica, Germany).

Reactive oxygen species measurement

The intracellular ROS levels were measured using a ROS assay kit (Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute, Nanjing, China), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. A fluorescence probe 2’,7’-dichlorofluorescin diacetate (DCFH-DA) was used to detect the ROS production, which was nonfluorescent until it was oxidized to form high levels of dichlorofluorescein (DCF) in the presence of ROS. Each group rats were perfusion with normal saline infusion after anesthetized, and then spinal cord tissue was removed and the fresh tissue was placed on ice to complete the following steps. 100 mg tissue was placed on a 300 mesh Nylon mesh, and a small dish was placed under the filter for collection and filtration. Firstly, adding 1 ml of red blood cell lysate stored at 4°C, and then cutting it into small pieces of about 2 mm with an ophthalmic scissors. Use ophthalmic forceps to drag the tissue onto the nylon mesh and grind it into slag. Rinse the red blood cell lysate until the tissue is finished. The cell suspension was collected, centrifuged at 500 g for 10 min, the supernatant was removed, and washed once with PBS, and the supernatant was discarded by centrifugation at 500 g/5 min. Resuspend in 500 μl PBS to prepare a single-cell suspension, the total number of cells should not be less than 106 cells. Then, the single-cell suspension was washed twice with PBS and incubated with DCFH-DA (10 μM) for 30 minutes at 37°C. After washing with PBS, the ROS-mediated fluorescence was examined by flow cytometry (Beckman, Germany) at excitation and emission wavelengths of 485 nm and 535 nm, respectively. The mean intensity was analyzed using the CytExpert analysis software.

Measurement of superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity

The activity for SOD in the spinal lumbar enlargement segments was assessed using a standard assay kit (Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute, Nanjing, China) based on the auto-oxidation of hydroxylamine. Then, the assay used the xanthine-xanthine oxidase system based on the production of superoxide ions, and the absorbance was measured at 550 nm.

Co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP)

For the co-immunoprecipitation, a total of 2 μg of mouse monoclonal anti-gp91phox (SC-130548, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) or control IgG (A7028, Beyotime) was added to 500 μg of tissue lysate with gentle rotation for two hour at 4°C. Subsequently, 20 μl of protein A/G PLUS-agarose beads (SC-2003, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) was added to the samples with gentle rotation overnight at 4°C. Then, the mixture was centrifuged at 2,500 g for five minutes, and the precipitate was washed for three times with cold phosphate-buffered saline. Finally, the protein sample was resolved on SDS-PAGE, and analyzed by western blot analysis with antibodies to NOX2 and Cav-1.

Statistical analysis

All data are expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). These results were analyzed using the SPSS (Version 22.0) statistical software. For multiple comparisons each value was compared by one way ANOVA following Dunnett test when each datum conformed to normal distribution. A P-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. The significance levels were assigned as *P<0.05, **P<0.01, and ***P<0.001.

Results

Validation of diabetic neuropathic pain rat models

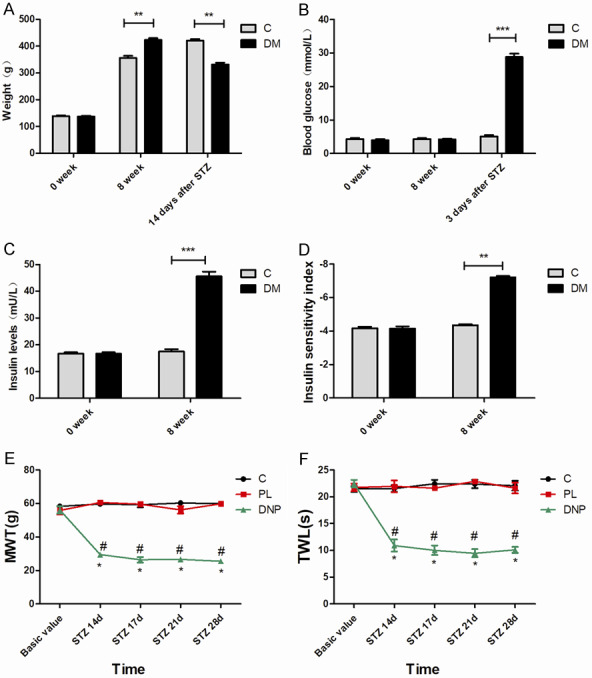

As presented in Figure 1A, there was no significant difference in body weight between control and diabetic rats before the diet (zero weeks). However, compared with the control group, the body weight of diabetic rats significantly increased at eight weeks after high-sugar and high-fat diet (P<0.01). After 14 days of single intraperitoneal streptozocin (STZ) injection, rats in the DM group exhibited a decrease in body weight, when compared with rats in the control group (P<0.01). In addition, the blood glucose levels on zero and eight weeks were similar between the control group and DM group (P>0.05). In contrast, the blood glucose levels of rats in the diabetes mellitus (DM) group were significantly elevated, when compared to rats in the C group, after three days of STZ injection (P<0.001, Figure 1B). Meanwhile, the high-fat and high-sugar diet for eight weeks significantly induced increase in plasma insulin levels in diabetic rats (P<0.001), but decreased the insulin sensitivity index (P<0.01), when compared to rats in the control group (Figure 1C, 1D). All rats in the DM group exhibited increased water intake and polyuria, according to these features, and high-fat-high-sugar-fed/low-dose STZ-treated rats induced sustained type-2 DM. However, there were no significant differences in mechanical withdrawal threshold (MWT) and thermal withdrawal latency (TWL) between the C group and PL group (P>0.05). Furthermore, rats in the DNP group presented with a significant reduction in MWT and TWL on day 14 (P<0.05), day 17 (P<0.05), day 21 (P<0.05) and day 28 (P<0.05) after STZ injection, when compared to rats in the control group, indicating the occurrence of mechanical allodynia and thermal hyperalgesia in rats in the DNP group (Figure 1E, 1F).

Figure 1.

The validation of diabetic neuropathic pain rat models. A. Body weight in the C group and DM group at zero weeks and eight weeks. B. The time course of blood glucose level changes in rats in the C group and DM group. C. Insulin levels of diabetic rats at zero weeks and eight weeks. D. The time course of insulin sensitivity index changes in diabetic rats and rats in the control group. E, F. The mechanical allodynia and thermal hyperalgesia of rats were measured at eight weeks and on day 14, 17, 21 and 28 after STZ injection; n=6. *P<0.05, compared with the control group at the corresponding time point; #P<0.05, compared with the PL group at the corresponding time point.

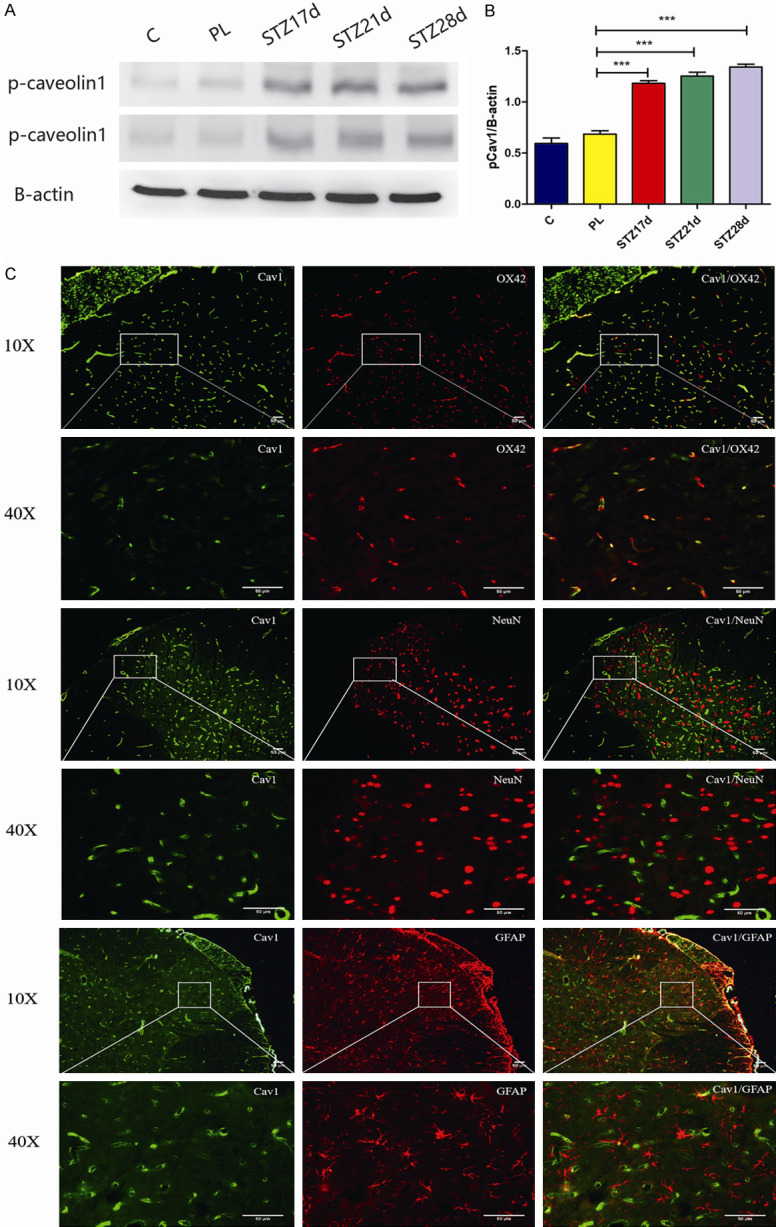

Increased expression of p-cav-1 in the spinal cord after DNP

In order to determine whether cav-1 in spinal cord was involved in the development of type-2 DNP, the alteration of cav-1 expression in type-2 DNP rats was examined. The western blot and immunohistochemistry results indicated that the expression level of total cav-1 (tCav-1) increased in the DNP group, when compared with the control and PL groups, respectively [15]. Furthermore, the western blot analysis also revealed that DNP produced a long-lasting (STZ 17 d, 21 d, 28 d) increase in p-cav-1 expression in the spinal cord (Figure 2A, 2B, P<0.001). Using the double-labeling immunofluorescence of cav-1 and OX42 (a marker of microglia), NeuN (a marker of neuron), or GFAP (a marker of astrocyte), it was revealed that cav-1 was mainly co-localized with OX42 in microglia, while the rest were co-localized with NeuN and GFAP (Figure 2C). This outomes was consisted with Jia et al. who found that cav-1 plays a role in DNP through the TLR4 signaling pathway and subsequent phosphorylation of NR2B [15].

Figure 2.

Increased expression of p-cav-1 in the spinal cord after diabetic neuropathic pain. (A) The western blot assay revealed that p-cav-1 expression increased in the spinal cord at 17, 21 and 28 days after STZ injection, when compared to the C group and PL group. (B) The quantification of western blot data obtained from (A). All data were presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM); n=4. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, and ***P<0.001. (C) The immunofluorescence staining revealed that the major cav-1 (green) co-localized in the microglia (OX42, red). Scale bar =50 μm.

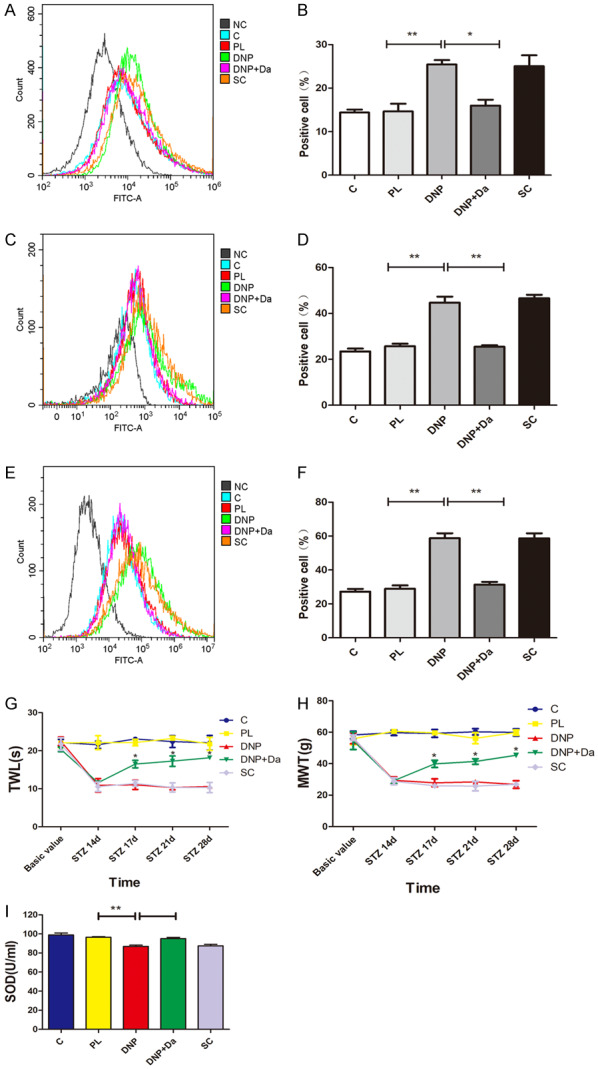

Daidzein inhibited the diabetic-induced increase in ROS production and oxidative stress in type-2 DNP

Next, the reactive oxygen species (ROS) and Superoxide Dismutase (SOD) were examined in the spinal cord at 17 days, 21 days and 28 days after STZ injection in each group of rats. The flow cytometry assay revealed that the ROS production increased in rats in the DNP group, when compared with the control group or PL group (Figure 3A-F, P<0.05). In order to determine whether the increased ROS production is involved in the cav1-induced mechanical allodynia and thermal hyperalgesia, rats in the DNP group were treated with the cav-1 specific inhibitor daidzein. Daidzein administration significantly reduced the ROS production and reversed the type-2 diabetic-induced mechanical allodynia and thermal hyperalgesia (Figure 3A-H, P<0.05). Furthermore, these diabetic rats exhibited a markedly reduced SOD activity (Figure 3I, P<0.05), and daidzein treatment reversed this reduction.

Figure 3.

The diabetic neuropathic pain increased the production of ROS and induced oxidative stress, while daidzein inhibited the ROS production and oxidative stress in type-2 DNP. (A, B) The flow cytometry reveals the change in ROS levels in the spinal cord at 17 days after STZ injection (the representative fluorescent shown in [A] and quantitative data shown in [B]). (C, D) The flow cytometry reveals the change in ROS levels in the spinal cord at 21 days after STZ injection (the representative fluorescent shown in [C] and quantitative data shown in [D]). (E, F) The flow cytometry reveals the change in ROS levels in the spinal cord at 28 days after STZ injection (the representative fluorescent shown in [E] and quantitative data shown in [F]). (G, H) The treatment with daidzein at 14 days after STZ injection significantly reversed the type-2 diabetes-induced thermal hyperalgesia (G) and mechanical allodynia (H) (n=4). *P<0.05, compared with the DNP group. (I) The standard assay kit reveals the activity of SOD in the spinal cord in rats from each group at 21 days after STZ injection. All data were presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM), n=4. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001.

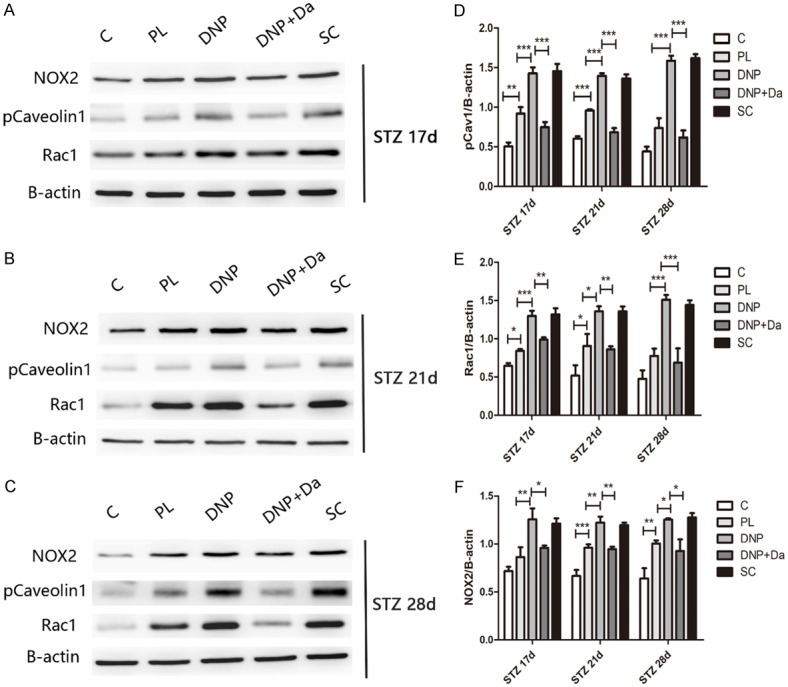

Phosphorylated caveolin-1 may increase ROS production through NOX2/Rac1 activation

In order to further determine whether NOX contributed to the cav-1-mediated ROS production in the spinal cord of diabetic rats, the NOX2 and Rac1 expression in spinal lumbar enlargement segments were measured under DNP conditions. NOX2 and Rac1 protein expression was significantly elevated in the spinal cord at 17 days, 21 days and 28 days after STZ injection (Figure 4, P<0.05). Hence, the administration of daidzein significantly inhibited these increases.

Figure 4.

Phosphorylated caveolin-1 may increase the ROS production through NOX2/Rac1 activation. (A-C) The western blot assay reveals that the p-caveolin-1, NOX2 and Rac1 expression changed in each group at 17 days (A), 21 days (B), and 28 days (C) after STZ injection. (D-F) The quantification of western blot data from [A-C] is shown. All data were presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM), n=4. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001.

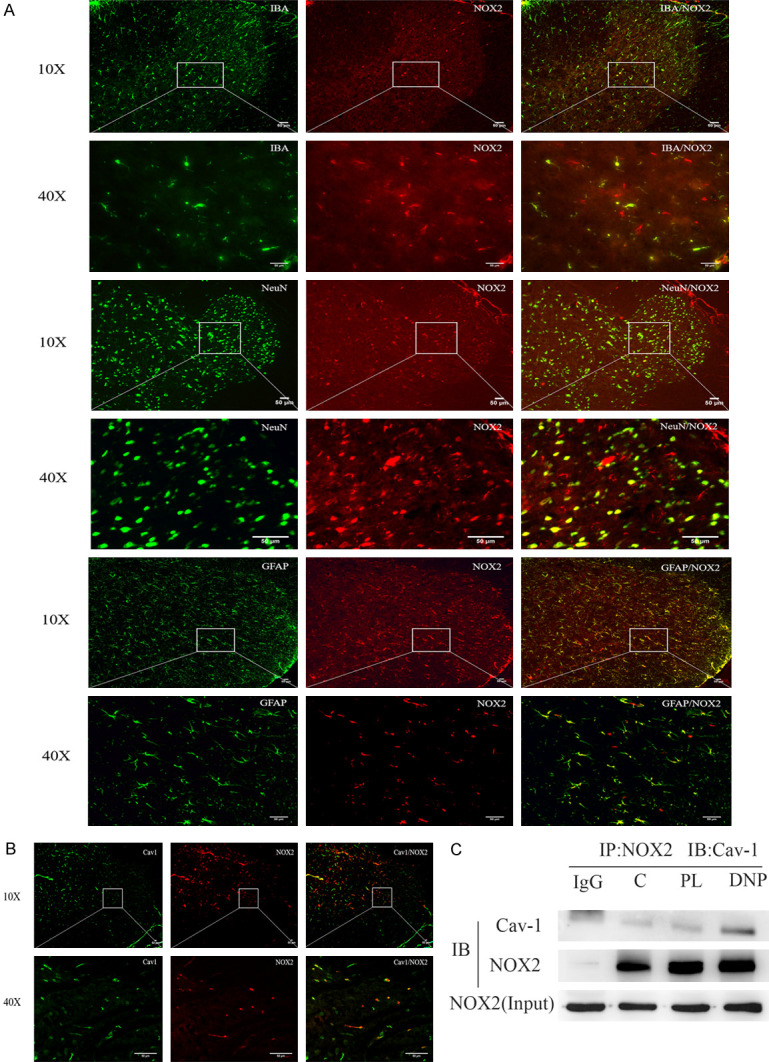

Interaction and co-localization of cav-1 with NOX2 in microglia in type-2 DNP rats

Next, the distribution of NOX2 in the spinal cord of type-2 DNP rats was determined using double-labeled immunofluorescence. The immunofluorescence staining analysis revealed that NOX2 co-localized with IBA, NeuN and GFAP in the spinal cord. Furthermore, NOX2 also co-expressed with cav-1 in the spinal cord. Hence, the co-immunoprecipitation assay revealed a direct interaction between cav-1 and NOX2 (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Cav-1 and NOX2 interacted together and co-localized in the microglia in type-2 diabetic neuropathic pain rats. A. The double-immunofluorescence shows that NOX2 mainly co-localized with the microglia and neuron in the spinal cord. B. The double-immunofluorescence revealed that cav-1 co-localized with NOX2 in the spinal cord. C. The representative western blot demonstrates the interaction of cav-1 and NOX2 in the co-immunoprecipitation experiment. Equal amounts of total lysates (500 g) were used for the immunoprecipitation with an NOX2-specific antibody, and the membranes were probed with a cav-1-specific antibody. Scale bar =50 μm.

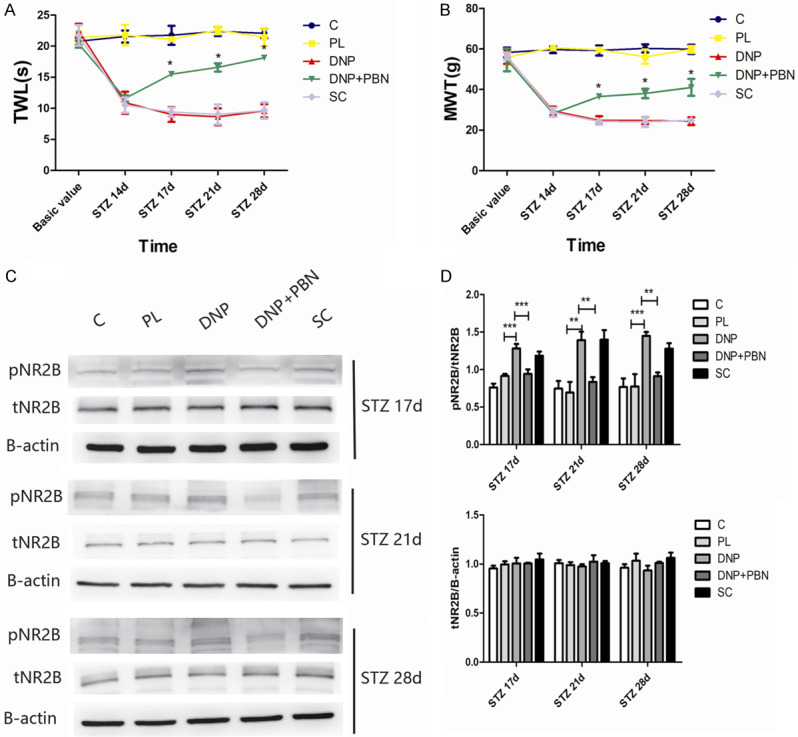

Systemic PBN blocked the diabetics-induced phosphorylation of NR2B

Finally, it was determined whether ROS contributed to the type-2 DM-induced pain hypersensitivity through the activation of NMDA receptors. In order to answer this question, the effect of the systemic administration of ROS scavenger PBN on p-NR2B and total NR2B in the spinal cord at 17 days, 21 days and 28 days after STZ injection in rats in each group was investigated. The treatment with PBN blocked the increase in expression of p-NR2B in the spinal cord of type-2 DNP rats. However, the PBN treatment had no effect on the total NR2B protein expression, when compared to the control group or PL group (Figure 6). Furthermore, the systemic administration of PBN also significantly relieved the type-2 diabetic-induced pain behavior.

Figure 6.

The systemic PBN reduced the phosphorylation of NR2B induced by type-2 diabetic neuropathic pain. (A, B) The treatment with PBN at 14 days after STZ injection significantly reversed the type-2 diabetes-induced thermal hyperalgesia (A) and mechanical allodynia (B) (n=4). *P<0.05, compared with the DNP group. (C) The western blot assay revealed that p-NR2B and total NR2B expression changed in each group at 17, 21 and 28 days after STZ injection. (D) Quantification of the western blot data obtained from [C]. All data were presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM), n=4. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001.

Discussion

The study revealed that cav-1 in the spinal cord contributes to type 2 DNP through the activation of the NOX2/Rac1/NR2B signaling pathway. The major findings are as follows: (1) the long-lasting increased p-cav1 expression in the spinal cord was linked with the development and maintenance of pain hypersensitivity and central sensitization, (2) cav-1 participated in the type-2 DNP possibly through its interaction with NOX2 and the promotion of ROS production in the spinal cord, and (3) the increase in ROS production contributed to the type-2 DNP via the activation of NMDA receptors. These findings reveal a novel mechanism for the regulation of type 2 DNP through cav-1 in the spinal cord.

Consistent with previous studies [13], the type-2 DNP model was established after rats were fed with high-sugar and high-fat diet, followed by intraperitoneal injection with a single 35-mg/kg dose of freshly prepared STZ. The model displayed spontaneous pain, mechanical allodynia and thermal hyperalgesia. These pain hypersensitivities occurred at 14 days after a single STZ injection, and lasted for more than two weeks. As expected, insulin resistance was induced at eight weeks after feeding with high-sugar and high-fat diet, while hyperglycemia was induced at three days after STZ injection. In addition, the pain behavior occurred at 14 days after STZ injection.

A growing body of evidence indicated that cav-1, which is the major structural protein essential for caveolae formation, functions as a scaffolding protein that regulates multiple physiological processes, including caveolae biogenesis, cell regulation, vesicular transport, inflammation, and signal transduction [16]. For example, the expression of the synapsin-driven cav-1 vector can enhance neuronal membrane/lipid raft formation, increase the expression of neurotransmitter and neurotrophin receptors, enhance NMDAR- and BDNF-mediated prosurvival kinase activation, elevate multiple neuronal pathways that converge to augment cAMP formation, and promote neuronal growth and arborization in primary neurons in vitro [17]. In hepatocytes, cav-1 is required for the TGF-β-mediated activation of TACE/ADAM17 through the phosphorylation of Src and NOX1-mediated ROS production [18]. The present study is first to report the functional role of cav-1 in type-2 DNP. It was observed that the upregulation of p-cav-1 expression in the spinal cord is associated with pain behavior and central sensitization in the rat model of STZ-induced type-2 DNP. Hence, persistent p-cav-1 upregulation may contribute to the development and maintenance of type-2 DNP.

Furthermore, in investigating the relationship between cav-1 and ROS, the present study revealed that the administration of cav-1 specific inhibitor daidzein decreased the p-cav1 expression, and subsequently resulted in the decrease in ROS production. Recently, various studies have reported that the connections between cav-1 and ROS levels play an important role in many diseases. Macrophages exposed to oxLDL increased its cav-1 expression, and cav-1 increased the NOX2 p47phox level, and acted as a switch for ROS production [19]. Furthermore, rVvhA, a virulent factor of Vibrio (V.) vulnificus, induced the swift phosphorylation of c-Src in the membrane lipid raft, which led to the increased interaction between cav-1 and NOX complex Rac1 for ROS production [20]. In HG-containing medium, the podocytes transfected with a recombinant plasmid GFP-cav-1 Y14F (mutation at a cav-1 phosphorylation site) revealed the significant downregulation of ROS production, when compared with those transfected with the control empty vector [9]. Moreover, cav-1 binds to Nox5 and Nox2, but not to Nox4, and suppresses the mRNA and protein expression of Nox2 and Nox4 through the inhibition of the NF-kB pathway [21]. The present study revealed that the expression of p-cav-1 significantly increased in the spinal cord of type-2 DNP. However, the administration with cav-1 specific inhibitor daidzein significantly decreased the ROS production and the expression of NOX2 and Rac1, but increased the SOD sensitivity. In addition, cav-1 participates in type-2 DNP by directly binding with NOX2 and promoting ROS production. These findings clearly demonstrate that the increase in p-cav-1 in the spinal cord contributes to type-2 DNP development and maintenance.

The present study revealed that NOX2 was detected in the microglia of the central nervous system, although NOX2 has also been recently measured in neurons [22]. Furthermore, the activation of NOX2 led to the translocation of cytosolic subunits to the membrane for the assembly of the holoenzyme. Rac1 activation plays a key role in the assembly of NADPH oxidase, which leads to tether p67phox to the membrane, and induces an “activating” conformational change in p67phox [23]. Consistent with these findings, it was observed that the activation of cav-1 can upregulate ROS levels via the Rac1-dependent NOX2 signaling pathway.

It is well-known that spinal cord central sensitization plays a key role in chronic neuropathic pain. The initiation and maintenance of spinal central sensitization relies on the activity of the receptors and signaling integration, especially the activation of NMDA receptors. NMDAR activation and its triggered downstream are required for the development of chronic neuropathic pain [24]. The p-NR2B subunit at Tyr1472 was significantly upregulated in the spinal cord after peripheral nerve injury, while no significant difference in total NR2B expression was detected [25].

A number of previous studies have shown that the removal of ROS alleviated the hyperalgesia and reserved the NMDAR phosphorylation to normal levels in the spinal cord [6]. The present study demonstrated that in the rat model of type-2 DNP, the ROS levels were significantly elevated. However, PBN reversed the enhancement of the NR2B subunit phosphorylation in the spinal cord, thereby relieving the mechanical allodynia and thermal hyperalgesia. These results suggest that NOX2-derived ROS plays a key role in the phosphorylation of NMDAR in the spinal cord, contributing to central sensitization and DNP.

Although the present study revealed that the removal of ROS reversed the enhancement of pNR2B expression and hyperalgesia, the mechanism of ROS involvement in central sensitization remains unknown. Free radicals and ROS are involved in various cellular processes. Lysosomal iron served as a catalyst in the production of ROS. The latter activated the PKC pathway, indicating that ROS may enhance NMDAR activity via the modulation of the PKC/Src/NR2A pathway, thereby modulating glutamatergic excitability [26]. Based on these findings, it can be concluded that the increased ROS production may upregulate the levels of activated PKC, which in turn enhances the NR2B subunit phosphorylation, thereby contributing to central sensitization and type-2 DNP.

Limitations. There were several limitatins in this study. Firstly, the mechanism of ROS involvement in central sensitization remains unknown which should be further research. Secondly, we only used the western blot to investigate the expression level of Rac1 and NOX2-NR2B, no datas about RT-PCR were provided in this present trial. Thirdly, this was only a animal trial, no relative vitro experiments were conducted which should be further research in the future.

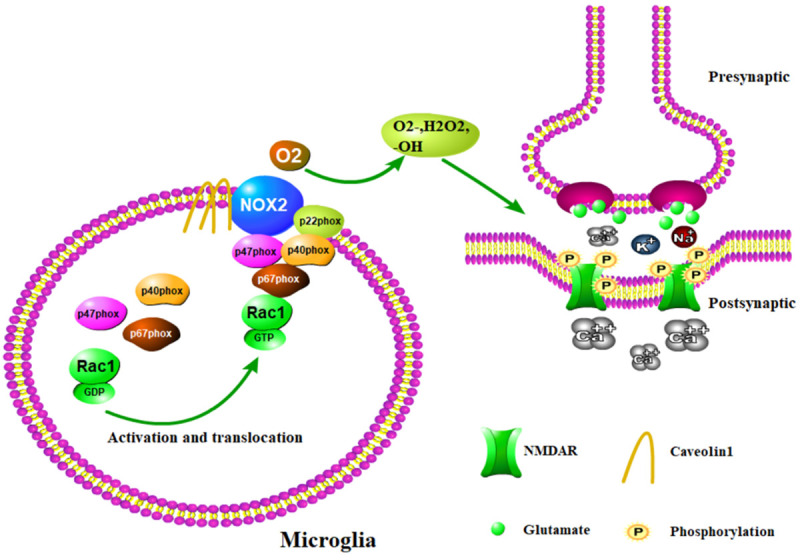

In conclusion, the present study revealed that cav-1 in the spinal cord modulates type-2 DNP via the regulation of the NOX2-ROS-NR2B phosphorylation signaling pathway. Given that the phosphorylation of NMDA receptor subunits in the spinal cord leads to central sensitization and ultimately contributes to type-2 DNP (Figure 7), these present findings may provide a novel targeted drug for treating type-2 DNP.

Figure 7.

The proposed role of cav-1 in type-2 diabetic neuropathic pain. Cav-1 interacts with NOX2, and NOX2 produces ROS. The latter regulates the NR2B subunit phosphorylation.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (Project No. 81771487) and Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (Project No. LY17H070006).

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Oza MJ, Kulkarni YA. Formononetin treatment in type 2 diabetic rats reduces insulin resistance and hyperglycemia. Front Pharmacol. 2018;9:739–750. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2018.00739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang TT, Xue R, Fan SY, Fan QY, An L, Li J, Zhu L, Ran YH, Zhang LM, Zhong BH, Li YF, Ye CY, Zhang YZ. Ammoxetine attenuates diabetic neuropathic pain through inhibiting microglial activation and neuroinflammation in the spinal cord. J Neuroinflammation. 2018;15:176–189. doi: 10.1186/s12974-018-1216-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nah J, Yoo SM, Jung S, Jeong EI, Park M, Kaang BK, Jung YK. Phosphorylated CAV1 activates autophagy through an interaction with BECN1 under oxidative stress. Cell Death Dis. 2017;8:e2822–e2834. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2017.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shiroto T, Romero N, Sugiyama T, Sartoretto JL, Kalwa H, Yan Z, Shimokawa H, Michel T. Caveolin-1 is a critical determinant of autophagy, metabolic switching, and oxidative stress in vascular endothelium. PLoS One. 2014;9:e87871–e87882. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0087871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.MacDonald JL, Fame RM, Gillis-Buck EM, Macklis JD. Caveolin1 identifies a specific subpopulation of cerebral cortex callosal projection neurons (CPN) including dual projecting cortical callosal/frontal projection neurons (CPN/FPN) eNeuro. 2018;5:e0234–e0237. doi: 10.1523/ENEURO.0234-17.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gao X, Kim HK, Chung JM, Chung K. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) are involved in enhancement of NMDA-receptor phosphorylation in animal models of pain. Pain. 2007;131:262–271. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2007.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Munoz FM, Gao R, Tian Y, Henstenburg BA, Barrett JE, Hu H. Neuronal P2X7 receptor-induced reactive oxygen species production contributes to nociceptive behavior in mice. Sci Rep. 2017;7:3539–3551. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-03813-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kallenborn-Gerhardt W, Schröder K, Geisslinger G, Schmidtko A. NOXious signaling in pain processing. Pharmacol Ther. 2013;137:309–317. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2012.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sun LN, Liu XC, Chen XJ, Guan GJ, Liu G. Curcumin attenuates high glucose-induced podocyte apoptosis by regulating functional connections between caveolin-1 phosphorylation and ROS. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2016;37:645–655. doi: 10.1038/aps.2015.159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Choi SR, Roh DH, Yoon SY, Kang SY, Moon JY, Kwon SG, Choi HS, Han HJ, Beitz AJ, Oh SB, Lee JH. Spinal sigma-1 receptors activate NADPH oxidase 2 leading to the induction of pain hypersensitivity in mice and mechanical allodynia in neuropathic rats. Pharmacoll Res. 2013;74:56–67. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2013.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xu C, Wang X, Gu C, Zhang H, Zhang R, Dong X, Liu C, Hu X, Ji X, Huang S, Chen L. Celastrol ameliorates Cd-induced neuronal apoptosis by targeting NOX2-derived ROS-dependent PP5-JNK signaling pathway. J Neuro. 2017;141:48–62. doi: 10.1111/jnc.13966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roberts HM, Grant MM, Hubber N, Super P, Singhal R, Chapple ILC. Impact of bariatric surgical intervention on peripheral blood neutrophil (PBN) function in obesity. Obes Surg. 2018;28:1611–1621. doi: 10.1007/s11695-017-3063-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dang JK, Wu Y, Cao H, Meng B, Huang CC, Chen G, Li J, Song XJ, Lian QQ. Establishment of a rat model of type II diabetic neuropathic pain. Pain Med. 2014;15:637–646. doi: 10.1111/pme.12387_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ma TC, Campana A, Lange PS, Lee HH, Banerjee K, Bryson JB, Mahishi L, Alam S, Giger RJ, Barnes S, Morris SM Jr, Willis DE, Twiss JL, Filbin MT, Ratan RR. A large-scale chemical screen for regulators of the arginase 1 promoter identifies the soy isoflavone daidzein a clinically approved small molecule that can promote neuronal protection or regeneration via a cAMP-independent pathway. J Neurosci. 2010;30:739–748. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5266-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jia GL, Huang Q, Cao YN, Xie CS, Shen YJ, Chen JL, Lu JH, Zhang MB, Li J, Tao YX, Cao H. Cav-1 participates in the development of diabetic neuropathy pain through the TLR4 signaling pathway. J Cell Physiol. 2019;235:2060–2070. doi: 10.1002/jcp.29106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fridolfsson HN, Roth DM, Insel PA, Patel HH. Regulation of intracellular signaling and function by caveolin. FASEB J. 2014;28:3823–31. doi: 10.1096/fj.14-252320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Head BP, Hu Y, Finley JC, Saldana MD, Bonds JA, Miyanohara A, Niesman IR, Ali SS, Murray F, Insel PA, Roth DM, Patel HH, Patel PM. Neuron-targeted caveolin-1 protein enhances signaling and promotes arborization of primary neurons. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:33310–33321. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.255976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moreno-Càceres J, Mainez J, Mayoral R, Martín-Sanz P, Egea G, Fabregat I. Caveolin-1-dependent activation of the metalloprotease TACE/ADAM17 by TGF-beta in hepatocytes requires activation of Src and the NADPH oxidase NOX1. FEBS J. 2016;283:1300–1310. doi: 10.1111/febs.13669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang J, Bai Y, Zhao X, Ru J, Kang N, Tian T, Tang L, An Y, Li P. oxLDL-mediated cellular senescence is associated with increased NADPH oxidase p47phox recruitment to caveolae. Biosci Rep. 2018;38 doi: 10.1042/BSR20180283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Song EJ, Lee SJ, Lim HS, Kim JS, Jang KK, Choi SH, Han HJ. Vibrio vulnificus VvhA induces autophagy-related cell death through the lipid raft-dependent c-Src/NOX signaling pathway. Sci Rep. 2016;6:27080–27094. doi: 10.1038/srep27080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen F, Barman S, Yu Y, Haigh S, Wang Y, Black SM, Rafikov R, Dou H, Bagi Z, Han W, Su Y, Fulton DJ. Caveolin-1 is a negative regulator of NADPH oxidase-derived reactive oxygen species. Free Radic Biol Med. 2014;73:201–213. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2014.04.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nayernia Z, Jaquet V, Krause KH. New insights on NOX enzymes in the central nervous system. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2014;20:2815–2837. doi: 10.1089/ars.2013.5703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pick E. Role of the Rho GTPase Rac in the activation of the phagocyte NADPH oxidase: outsourcing a key task. Small GTPases. 2014;5:e27952–e27975. doi: 10.4161/sgtp.27952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Inquimbert P, Moll M, Latremoliere A, Tong CK, Whang J, Sheehan GF, Smith BM, Korb E, Athié MCP, Babaniyi O, Ghasemlou N, Yanagawa Y, Allis CD, Hof PR, Scholz J. NMDA receptor activation underlies the loss of spinal dorsal horn neurons and the transition to persistent pain after peripheral nerve injury. Cell Rep. 2018;23:2678–2689. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.04.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen SR, Samoriski G, Pan HL. Antinociceptive effects of chronic administration of uncompetitive NMDA receptor antagonists in a rat model of diabetic neuropathic pain. Neuropharmacology. 2009;57:121–126. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2009.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.White RS, Bhattacharya AK, Chen Y, Byrd M, McMullen MF, Siegel SJ, Carlson GC, Kim SF. Lysosomal iron modulates NMDA receptor-mediated excitation via small GTPase, Dexras1. Mol Brain. 2016;9:38–52. doi: 10.1186/s13041-016-0220-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]