Abstract

Background

The safety of performing spinal anaesthesia for both patients and anaesthetists alike in the presence of active infection with the novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is unclear. Here, we report the clinical characteristics and outcomes for both patients with COVID-19 and the anaesthetists who provided their spinal anaesthesia.

Methods

Forty-nine patients with radiologically confirmed COVID-19 for Caesarean section or lower-limb surgery undergoing spinal anaesthesia in Zhongnan Hospital, Wuhan, China participated in this retrospective study. Clinical characteristics and perioperative outcomes were recorded. For anaesthesiologists exposed to patients with COVID-19 by providing spinal anaesthesia, the level of personal protective equipment (PPE) used, clinical outcomes (pulmonary CT scans), and confirmed COVID-19 transmission rates (polymerase chain reaction [PCR]) were reviewed.

Results

Forty-nine patients with COVID-19 requiring supplementary oxygen before surgery had spinal anaesthesia (ropivacaine 0.75%), chiefly for Caesarean section (45/49 [91%]). Spinal anaesthesia was not associated with cardiorespiratory compromise intraoperatively. No patients subsequently developed severe pneumonia. Of 44 anaesthetists, 37 (84.1%) provided spinal anaesthesia using Level 3 PPE. Coronavirus disease 2019 infection was subsequently confirmed by PCR in 5/44 (11.4%) anaesthetists. One (2.7%) of 37 anaesthetists who wore Level 3 PPE developed PCR-confirmed COVID-19 compared with 4/7 (57.1%) anaesthetists who had Level 1 protection in the operating theatre (relative risk reduction: 95.3% [95% confidence intervals: 63.7–99.4]; P<0.01).

Conclusions

Spinal anaesthesia was delivered safely in patients with active COVID-19 infection, the majority of whom had Caesarean sections. Level 3 PPE appears to reduce the risk of transmission to anaesthetists who are exposed to mildly symptomatic surgical patients.

Keywords: COVID-19, perioperative clinical characteristics, spinal anaesthesia, surgery

Editor's key points.

-

•

The novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is associated with human-to-human transmission.

-

•

Exposure to COVID-19 may result in acute respiratory failure for healthcare workers.

-

•

The risk of emergent surgery, including Caesarean section, where spinal anaesthesia is the optimal choice for both patients and healthcare providers, is unclear.

-

•

Spinal anaesthesia was delivered safely in patients (mostly women requiring Caesarean sections) with active, although mild, COVID-19 infection.

-

•

Level 3 personal protective equipment appears to reduce the risk of transmission to anaesthetists who are exposed to mildly symptomatic surgical patients.

The emergence of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), termed coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), in Wuhan, Hubei Province, China since early December 20191 , 2 has brought the healthcare system to a standstill. As of March 3, 2020, 80 303 confirmed cases have been documented in China. The highly infectious features of SARS-CoV-2 have resulted in a public health emergency of international concern, as declared by the WHO.

Several reports have now described the epidemiological, clinical, laboratory, and radiological characteristics of patients with confirmed COVID-19, including pregnant women who undergo Caesarean section. However, the perioperative characteristics and anaesthetic management of surgical patients with confirmed COVID-19, including those undergoing Caesarean section, have not been reported, although clinical recommendations have recently been published.3

As person-to-person transmission of COVID-19 occurs in hospitals,4, 5, 6 surgical procedures, in which neuraxial techniques are usually deemed to provide optimal anaesthesia, may place clinicians at particularly high risk when caring for infected patients. The objective of this report was to share our experience of performing spinal anaesthesia in patients with COVID-19, by reporting the perioperative characteristics and outcome of surgical patients in whom spinal anaesthesia was undertaken. In addition, we report the possible impact of spinal anaesthesia on anaesthetists after exposure to COVID-19.

Methods

Study design

This was a single-centre, retrospective study conducted at Zhongnan Hospital of Wuhan University between January 1, 2020 and February 14, 2020. The study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Board of Zhongnan Hospital of Wuhan University (reference: 2020049). Verbal consent was obtained from patients and anaesthetists.

Participants

Patients undergoing spinal anaesthesia were enrolled if they had clinically confirmed COVID-19, in accord with current diagnostic criteria.7 We also identified the anaesthesiologists who delivered clinical care to patients confirmed as having COVID-19 during surgery, but who had no contact with confirmed COVID-19 patients beyond the operating theatre.

Confirmation of COVID-19 diagnosis

Throat swab samples obtained from patients and anaesthetists were tested for SARS-CoV-2 with the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention recommended reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT–PCR) test (BioGerm, Shanghai, China). Coronavirus disease 2019 infection was confirmed by a positive RT–PCR test result undertaken in the clinical laboratory of Zhongnan Hospital.

Data collection: surgical patients

We extracted data detailing sex, age, operation type, clinical characteristics (including symptoms/signs, blood test results, chest CT scans, and throat swab nucleic acid), and type of surgery from electronic medical records. Heart rate, oxygen saturation, and noninvasive blood pressure at the start of anaesthesia and after 5 min of the end of anaesthesia for all patients were compared. Leucocyte counts before and 3 days after surgery were also recorded.

Data collection: anaesthetists

We analysed data from anaesthetists who had directly cared (within 1 m proximity) for patients with confirmed COVID-19, but who had no contact with patients with COVID-19 outside the hospital. We recorded sex, age, and clinical characteristics (including the development of symptoms/signs, blood test results, chest CT scans, and throat swab testing for COVID-19). We also recorded the personal protective equipment (PPE) worn by each anaesthetist undertaking spinal anaesthesia, as defined by the EU Regulation 2016/425. Category 3 PPE is required when the highest level of respiratory, skin, eye, and mucous membrane protection is needed, including positive pressure (pressure demand), self-contained breathing apparatus, and a fully encapsulating chemical protective suit plus inner and outer chemical resistant gloves. Category 1 PPE is limited to surgical mask, hat, gloves, and gowns.

Statistical analysis

Two study investigators (JJZ and HXJ) independently reviewed all data to verify accuracy. Descriptive data are presented as mean (standard deviation) (or median [inter-quartile range]) for continuous variables, and n (%) for categorical variables. We used Wilcoxon's signed-rank test for paired non-parametric comparisons. We assessed different frequency rates between different levels of PPE using the χ2 test. Statistical analysis was performed using the SPSS 21.0 statistical software (SPSS, Inc. Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

Patient characteristics

We identified 49 patients with radiologically confirmed COVID-19. The patient characteristics and symptoms are summarised in Table 1 . Fever was the most common symptom. Positive confirmation of COVID-19 by RT–PCR was recorded in 13/49 (26.5%) patients. Every patient required supplemental oxygen (delivered by nasal cannula) before surgery.

Table 1.

Characteristics of surgical patients with COVID-19 infection. Data are presented as median (IQR) or n (%). ASA, American Society of Anesthesiologists; COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; IQR, inter-quartile range; RT–PCR, reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction.

| Characteristics | N |

|---|---|

| Age, Median (IQR), y | 31 (29–34) |

| Female sex | 42 (85.7%) |

| BMI, Median (IQR), kg/m2 | 35.2 (33.25–36.4) |

| Duration from onset of symptoms to radiological confirmation of pneumonia, Median (IQR), days | 3 (5–8) |

| Duration from onset of symptoms to operation room, Median (IQR), days | 2 (0.5–3) |

| Symptom | |

| Cough | 21 (42.8%) |

| Sore throat | 14 (28.6%) |

| Myalgia | 6 (12.2%) |

| Shortness of breath | 4 (8.2%) |

| Gastrointestinal reaction | 2 (4.0%) |

| Fever(°C) | |

| <37.3 | 23 (46.9%) |

| 37.3–37.9 | 21 (42.9%) |

| 38.0–38.9 | 3 (6.1%) |

| >=39 | 2 (4.1%) |

| Positive RT-PCR for COVID-19 | 13 (26.5%) |

| Comorbidities | |

| Hypertension | 4 (8.2%) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 2 (4.1%) |

| Thyroid dysfunction | 2 (4.1%) |

| Operation type | |

| Caesarean section | 45 (91.8%) |

| Orthopedic | 4 (8.2%) |

| ASA physical status | |

| 1 | 43 (87.8%) |

| 2 | 6 (12.2%) |

| Treatment | |

| Nasal cannula | 49 (100%) |

| Antiviral agents | 29 (59.2%) |

| Antibacterial agents | 47 (95.9%) |

| Progress to severe Pneumonia | |

| Yes | 0 (0%) |

| No | 100 (100%) |

| Complication | |

| Vomit | 3 (6.1%) |

Spinal anaesthesia

Spinal anaesthesia was performed in the lateral decubitus position at the level of L3–L4. After local skin infiltration with lidocaine 2% (2 ml), isobaric ropivacaine 0.75% (2.2 ml) was injected intrathecally using 25-gauge needles. Spinal anaesthesia was well tolerated, with heart rate, blood pressure, and oxygen saturation remaining stable after surgery. Prophylactic anti-emetics were administered to decrease the risk of vomiting and viral spread.

Postoperative outcomes

Three (6.1%) of 49 patients vomited after spinal anaesthesia was established. After surgery, the total leucocyte count and neutrophil counts were higher, accompanied by a lower lymphocyte count (Table 2 ). No surgical patients developed severe pneumonia or died of COVID-19 pneumonia after surgery, as of February 14, 2020 (Table 1).

Table 2.

Perioperative characteristics of surgical patients with coronavirus disease 2019 infection. ∗Laboratory values obtained 3 days after surgery.

| Variable | Before surgery | After surgery | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total leucocytes (109 L−1) | 8.0 (6.5–10.5) | 9.2 (6.3–11.3)∗ | 0.01 |

| Neutrophil count (109 L−1) | 6.3 (4.6–9.1) | 7.4 (5.1–9.5)∗ | 0.01 |

| Lymphocyte count (109 L−1) | 1.38 (0.96–1.72) | 1.33 (0.77–1.6)∗ | <0.01 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 128 (120–144) | 124 (116–134) | 0.12 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 80 (73–85) | 78 (70–88) | 0.75 |

| Heart rate (beats min−1) | 84 (84–95) | 84 (84–94) | 0.55 |

| Oxygen saturation (%) | 100 (99–100) | 100 (99–100) | 0.45 |

Anaesthetists

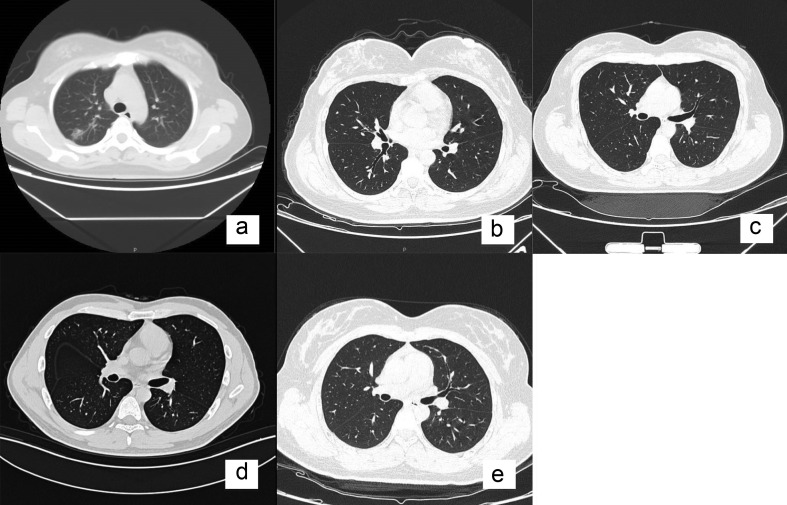

Forty-four anaesthetists (30 females; 68.2%) had direct contact with patients with COVID-19. Of these 44 anaesthetists, 26 (59%) were taking umifenovir, a broad-spectrum antiviral compound that blocks membrane fusion between the virus and target host cells. The majority of the staff wore Level 3 PPE in the operating theatre (Table 3 ). Coronavirus disease 2019 infection was subsequently confirmed by PCR in five/44 (11.4%) anaesthetists. Of 37 anaesthetists who wore Category 3 PPE, one (2.7%) developed PCR-confirmed COVID-19 compared with four/seven (57.1%) anaesthetists who had Category 1 protection in the operating theatre (relative risk reduction: 95.3% [95% confidence intervals: 63.7–99.4]; P<0.01) (Table 4 ). Of the five anaesthetists who were infected (Table 5), none had family members with COVID-19. Although the symptoms were mild, two required hospital treatment for supplementary oxygen despite mostly normal pulmonary CT scans (Fig. 1 ). The other three anaesthetists were quarantined at home. All five anaesthetists were treated with antiviral and antibacterial agents (Table 5 ).

Table 3.

Characteristics of 44 anaesthetists who cared for patients with coronavirus disease 2019 infection. Data are presented as median (inter-quartile range) or n (%).

| Characteristic | |

|---|---|

| Age (yr) | 33 (28–35) |

| Female gender | 30 (68.2) |

| BMI (kg m−2) | 23.1 (21.9–24.8) |

| Level 3 personal protective equipment | 37 (84.1) |

| Operative time (h) | 3.8 (2–5) |

Table 4.

Symptoms of anaesthetists at time of delivering spinal anaesthesia. Data are presented as n (%). PCR, polymerase chain reaction; PPE, personal protective equipment.

| Characteristic | Total (n=44) | Level 3 PPE (n=37) | Level 1 PPE (n=7) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female sex | 30 (68.2) | 25 (67.6) | 5 (71.4) | 0.61 |

| Symptoms | ||||

| Fever | 1 (2.3) | 1 (2.7) | 0 (0) | 0.84 |

| Fatigue | 8 (18.2) | 6 (16.2) | 2 (28.6) | 0.38 |

| Cough | 19 (35) | 18 (48.6) | 1 (14.3) | 0.10 |

| Myalgia | 7 (15.9) | 6 (16.2) | 1 (14.3) | 0.69 |

| Sore throat | 10 (22.7) | 9 (24.3) | 1 (14.3) | 0.49 |

| Diarrhoea | 4 (9.1) | 3 (8.1) | 1 (14.3) | 0.51 |

| Headache | 11 (25) | 9 (24.3) | 2 (28.6) | 0.57 |

| Umifenovir therapy | 26 (59.1) | 23 (62.2) | 3 (42.9) | 0.29 |

| PCR confirmed | 5 (11.4) | 1 (2.7) | 4 (57.1) | <0.01 |

| CT confirmed | 1 (2.3) | 0 (0) | 1 (14.3) | 0.16 |

Table 5.

Clinical characteristics of anaesthetists who acquired COVID-19 after delivering spinal anaesthesia. ∗Quarantined at home. †Each individual infected anaesthetist. COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; RT–PCR, reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction.

| 1† | 2† | 3† | 4† | 5† | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | |||||

| Age (yr) | 48 | 40 | 30 | 34 | 28 |

| Gender | Female | Female | Female | Male | Female |

| Family members affected | No | No | No | No | No |

| Coexisting conditions | No | No | No | No | No |

| Symptoms | |||||

| Fever | No | No | No | No | No |

| Fatigue | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Myalgia | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Malaise | No | No | No | No | No |

| Cough | No | No | No | No | No |

| Sore throat | No | No | No | No | No |

| Chest pain | No | No | No | No | No |

| Diarrhoea | No | No | No | No | No |

| COVID-19 diagnostic tests | |||||

| RT–PCR | Positive | Positive | Positive | Positive | Positive |

| CT scan | Positive | Negative | Negative | Negative | Negative |

| Treatment | |||||

| Location | Hospital | Hospital | Home∗ | Home∗ | Home∗ |

| Antivirals | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Antibiotics | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Supplementary oxygen | Yes | Yes | No | No | No |

Fig 1.

Chest CT scans (transverse plane) of five anaesthetists infected with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). (a) Anaesthetist 1: multiple bilateral ground-glass opacities, most prominent on the right. (b–e) Anaesthetists 2–5: no changes on CT scan despite confirmation of COVID-19 via reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction tests on throat swab sample.

Discussion

This is the largest case series exploring the risk for anaesthetists of developing COVID-19 through exposure to infected surgical patients undergoing spinal anaesthesia. The clinical characteristics of the 49 infected surgical patients were typical of the majority of adults with COVID-19 infection.8 We found that spinal anaesthesia had no adverse effects, either during the intraoperative period or subsequently. However, based on our follow-up of 44 anaesthetists who delivered spinal anaesthesia, our data suggest that Level 3 PPE is likely to reduce the risk of acquiring COVID-19.

Spinal anaesthesia is the anaesthetic of choice for many surgical procedures, in particular Caesarean sections.9 However, whether the risk of spinal anaesthesia to anaesthetists being undertaken in patients with COVID-19 is uncertain. Using ropivacaine, we found that spinal anaesthesia had no adverse impact during the intraoperative period.10 Typical changes in leucocyte count were observed after surgery.11 Most importantly, spinal anaesthesia did not appear to worsen the outcome of patients with SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia.

Level 3 PPE12 was used by most anaesthetists, but seven anaesthetists used Level 1 protection because of delayed confirmation of COVID-19 in patients undergoing surgery. Our study provides further evidence of human-to-human transmission in hospitals, although this is lower than previous reports.13 Most infected anaesthetists had mild symptoms. The low transmission rate may, however, be attributable to additional factors. First, most operating theatres are under positive pressure with up to 20 room air exchanges per hour, thereby reducing viral exposure rapidly.14 Second, all surgical patients in this study had mild symptoms. Third, several anaesthetists were fully protected and took prophylactic drugs.

We confirmed previous studies demonstrating that asymptomatic infected anaesthetists, as confirmed by PCR, frequently do not have concomitant radiological abnormalities.15 False-negative PCR testing for throat swabs has been documented during this outbreak, highlighting the importance of clinical symptoms (fever, fatigue, dry cough, myalgia, and dyspnoea) in recognising COVID-19 at an early stage.16

This study clearly has multiple limitations. First, throat swabs were used to diagnose COVID-19 through RT–PCR, rather than blood samples. False-negative tests may occur using throat swab samples. Second, as most patients with COVID-19 undergoing surgery had mild symptoms, we cannot address whether tracheal intubation/extubation is similarly, or more, hazardous compared with regional anaesthesia. We also cannot exclude that anaesthetists became infected through other sources (e.g. colleagues in the hospital).

In summary, spinal anaesthesia appears to be safe in mildly symptomatic COVID-19 patients. Our study suggests that using Level 3 PPE is likely to reduce the risk to anaesthetic staff of acquiring COVID-19 even from patients with mild symptoms. Considering the significance of this ongoing global public health emergency, our report contributes valuable data to inform the perioperative community.

Authors' contributions

Study design: ZZZ, JJK, FZ

Study conduct: QZ, YYL, YYC, YFZ

Data collection: HXJ, JJZ, ZL, XY

Statistical analysis: QZ, QL, MM, HL, LJT

Writing of paper: QZ, YYL

Critical revision: all authors.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all patients and anaesthetists involved in the study.

Handling editor: Gareth Ackland

Contributor Information

Ying Y. Chen, Email: chenyingy@whu.edu.cn.

Feng Zheng, Email: fengzheng@whu.edu.cn.

Jian J. Ke, Email: 1219628972@qq.com.

Zong Z. Zhang, Email: zhangzz@whu.edu.cn.

Declarations of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Funding

Natural Science Foundation of Hubei Province, China (2019CFB106); Cultivation fund from Zhongnan Hospital, Wuhan University (znpy2018092); Young teacher funding program from Wuhan University (2042018kf0197).

References

- 1.Lu H., Stratton C.W., Tang Y.W. Outbreak of pneumonia of unknown etiology in Wuhan, China: the mystery and the miracle. J Med Virol. 2020;92:401–402. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Paules C.I., Marston H.D., Fauci A.S. Coronavirus infections—more than just the common cold. JAMA. 2020;323:707–708. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.0757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Peng P.W.H., Ho P.-L., Hota S.S. Outbreak of a new coronavirus: what anaesthetists should know. Br J Anaesth. 2020;124:497–501. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2020.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chan J.F., Yuan S., Kok K.H. A familial cluster of pneumonia associated with the 2019 novel coronavirus indicating person-to-person transmission: a study of a family cluster. Lancet. 2020;395:514–523. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30154-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Phan L.T., Nguyen T.V., Luong Q.C. Importation and human-to-to human transmission of a novel coronavirus in Vietnam. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:872–874. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2001272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rothe C., Schunk M., Sothmann P. Transmission of 2019-nCoV infection from an asymptomatic contact in Germany. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:970–971. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2001468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.National Health Commission of China . 5th edn. Feb 21, 2020. New coronavirus pneumonia prevention and control program.http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/zhengceku/2020-02/22/5482010/files/310fd7316a89431d977cc8f2dbd2b3e0.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huang C., Wang Y., Li X. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395:497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nganga N.W. Spinal anaesthesia: advantages and disadvantages. East Afr Med J. 2010;87:225–226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang H., Gao Q., Xu R. The efficacy of ropivacaine and bupivacaine in the caesarean section and the effect on the vital signs and the hemodynamics of the lying-in women. Saudi J Biol Sci. 2019;26:1991–1994. doi: 10.1016/j.sjbs.2019.07.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sahoo A.K., Panda N., Sabharwal P. Effect of anesthetic agents on cognitive function and peripheral inflammatory biomarkers in young patients undergoing surgery for spine disorders. Asian J Neurosurg. 2020;14:1095–1105. doi: 10.4103/ajns.AJNS_173_19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen X.D., Shang Y., Yao S.L. Perioperative care provider’s considerations in managing patients with the COVID-19 infections. Transl Perioper Pain Med. 2020;7:216–223. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li Q., Guan X., Wu P. Early transmission dynamics in Wuhan, China, of novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia. N Engl J Med Adv Access Published on January. 2020;29 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kamming D., Gardam M., Chung F. Anaesthesia and SARS. Br J Anaesth. 2003;90:715–718. doi: 10.1093/bja/aeg173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guan W.J., Ni Z.Y., Hu Y. Clinical characteristics of 2019 novel coronavirus infection in China. N Engl Med published on February. 2020;28 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang D., Hu B., Hu C. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA. 2020;323:1061–1069. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]