Dear Editor,

In the past five years, we have developed a behavioral model of empathy for pain in rats [1–5]. Experimentally, at least two types of behaviors associated with empathy for pain in rats can be identified, based on the evolutionary notion of the Russian doll model [6]. One has been referred to as an observer’s empathic consolation, which is driven by social interaction with a demonstrator in pain [3, 7–9]; the other is referred to as observational contagious pain (OCP or empathic transfer of pain) from a distressed object to a witnessing subject [1–3, 5]. Briefly, the consolation in rat observers has been identified as allolicking and allogrooming behaviors toward a familiar conspecific in pain during a 30-min priming dyadic social interaction (PDSI) [3, 8, 9]. Allolicking can be defined as an observer’s sustained licking action at a demonstrator’s injury site, while allogrooming can be defined as an observer’s head contact with the head or body of a demonstrator in pain, accompanied by rhythmic head movement [3, 4, 8]. The bouts of allolicking and allogrooming behaviors can be captured by video recorder and analyzed qualitatively and quantitatively off-line (see Supplementary Methods) [4]. Meanwhile, OCP, also referred to as empathic pain hypersensitivity in our previous reports, has been identified qualitatively and quantitatively as lowered pain threshold or increased pain sensitivity in a rat observer after the PDSI with a demonstrator in pain [1–3]. OCP remains unchanged for at least 5 h after the PDSI [2, 3]. Although allogrooming behavior can be seen in both familiar and unfamiliar conspecifics during the PDSIs, allolicking behavior and OCP can only be seen in a familiar observer, suggesting that the establishment of familiarity among conspecifics is essential to the induction of empathic responses to another’s pain in rats [2, 3, 5]. However, the model has only been validated in male but not female rats. Moreover, so far a mouse model of empathy for pain has not been available although models of observational fear learning have been well established [5]. Whether species and sex differences exist for this paradigm is unknown. Thus, to answer the above common questions, we further designed and studied the behavioral parameters associated with OCP and consolation qualitatively and quantitatively in both male and female mice and rats.

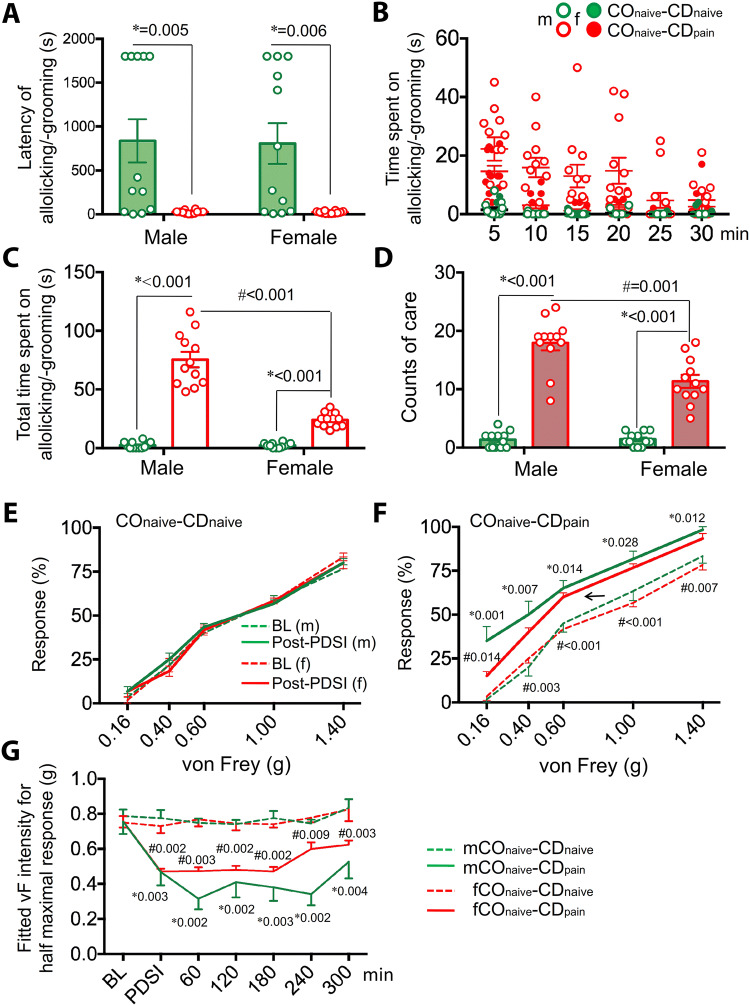

In this study, male and female C57BL/6 (B6) mice and Sprague-Dawley albino rats were used. Regardless of species, the dyads of animals used for social interaction, which were of the same sex and familiar to each other, were designed as two paradigms: (1) COnaive–CDnaive, a control paradigm for dyadic social interaction between a naive cagemate observer and a naive cagemate demonstartor; and (2) COnaive–CDpain, an experimental paradigm for dyadic social interaction between a naive cagemate observer and a cagemate demonstartor in pain (for details see Supplementary Methods and Fig. S1) [4]. The mouse and rat observers in the COnaive–CDpain paradigm both showed more consolation behaviors toward a conspecific in pain than the observers in the COnaive–CDnaive paradigm (Fig. 1A–D for mice, Fig. 2A–D for rats, and Supplementary Tables S1–S2). Generally, both mouse and rat observers had a shorter latency and spent more time and visit counts engaged in allolicking and allogrooming when witnessing a conspecific in pain (Figs. 1A–D, 2A–D). Interestingly, the mouse observers also had allo-mouth sniffing behavior, but in contrast the rat observers did not (Supplementary Tables S1–S2). Both mouse and rat observers showed allo-tail sniffing and self-grooming behaviors as previously described (Supplementary Tables S1–S2) [7].

Fig. 1.

Empathic consolation and observational contagious pain in male and female mouse observers. A–D Latency (A), time course (B), total time (C), and visit counts (D) when the mouse observers engaged in allolicking and allogrooming behaviors during 30-min priming dyadic social interactions (PDSIs) with a cagemate demonstrator of the same sex in pain. E, F Examples of stimulus-response curves (SRCs) prior to (BL) and 60 min after a PDSI in male (m) and female (f) mouse observers in the COnaive–CDnaive and COnaive–CDpain paradigms. G Time courses of changes in von Frey intensity (g) for half maximal response from the SRCs of mouse observers in the COnaive–CDnaive and COnaive–CDpain paradigms (BL, baseline; n = 12 males, n = 12 females; mean±SEM; *P < 0.05, COnaive–CDpainvs COnaive–CDnaive; #P < 0.05 female vs male in the COnaive–CDpain paradigm, two-tailed Mann-Whitney U test). See supplementary Tables S1, S3 and S4 for details.

Fig. 2.

Empathic consolation and observational contagious pain in male and female rat observers. A–D Latency (A), time course (B), total time (C), and visit counts (D) when the rat observers engaged in allolicking and allogrooming behaviors during 30-min PDSI with a cagemate demonstrator of the same sex in pain. E Time courses of changes in paw withdrawal mechanical threshold (g) of rat observers in the COnaive–CDnaive and COnaive–CDpain paradigms (BL, baseline; n = 8–12 males, n = 9–11 females; mean ± SEM; *P < 0.05, COnaive–CDpainvs COnaive–CDnaive, two-tailed Mann-Whitney U test). See supplementary Tables S2, S3 and S4 for details.

There were no species differences in consolation (latency, total time, and visit count of allolicking and allogrooming) between mice and rats in either males or females (Table S3). Species differences between mice and rats were not revealed in allo-tail sniffing in terms of latency and total time in either males or females (Table S3). Although male mice had more visit counts than male rats (P = 0.002, Mann-Whitney U test), no species difference was found between female mice and rats for allo-tail sniffing counts (Table S3). As for non-social behavior, rats of both sexes spent more time on self-grooming than mice of both sexes (Table S3, mice vs. rats: P = 0.017 for males and P = 0.016 for females, Mann-Whitney U test) although the counts showed no species difference. Moreover, rats of both sexes had a shorter latency in self-grooming than mice of both sexes although a statistically significant species difference was only seen in males (Table S3, P = 0.001, Mann-Whitney U test). Taking the latency and time course data together, we found that both mouse and rat observers, either male or female, were likely to approach a conspecific in pain as quickly as possible and spent more time on consolation and social behaviors than on self-grooming behavior (Figs. 1A, 1B, 2A, 2B, and Tables S1 and S2).

In mice, a distinct sex difference was found in both empathic consolation and general social behaviors in terms of time and counts, but there was no sex difference for latency (Fig. 1A–D and Table S1). Male mice spent more time and had higher visit counts than females in allolicking/allogrooming and allo-mouth/allo-tail sniffing toward a conspecific in pain during the first 20 min of PDSIs (Fig. 1C, D and Table S1), while there was no sex difference in self-grooming in terms of latency, time, and count (Table S1). In rats, no sex difference was seen in either empathic consolation or general social behavior in terms of latency, time, and count (Fig. 2A–D and Table S2). Although female rats had a relatively shorter latency than males (P = 0.019, Mann-Whitney U test), no sex difference was seen in time and count for self-grooming behavior (Table S2).

Similar to our previous and present reports on rats [1–4], OCP also occurred in naive mouse observers in the COnaive–CDpain paradigm after 30-min PDSI (Fig. 1F–G and Fig. S2G–L), but OCP was not identified in mouse observers in the COnaive–CDnaive paradigm (Fig. 1E and Fig. S2A–F). Both male and female mouse observers presented long-term mechanical pain hypersensitivity after a PDSI with a conspecific in pain, as evidenced by a significant leftward shift of the stimulus-response curves from baseline (Fig. 1F and Fig. S2G–L) and a lower paw withdrawal threshold (von Frey intensity for half maximal response; Fig. 1G). The OCP identified in the mouse observers in the COnaive–CDpain paradigm did not disappear after a PDSI until 240 min in females and 300 min in males (Fig. 1G and Fig. S2G–L).

Generally, no species difference in OCP was revealed between mice and rats of either sex in terms of magnitude and time course under the same experimental condition, procedure, and paradigm (Figs. 1E–G, 2E, and Fig. S2).

No sex difference was revealed in OCP between male and female observers in either mice or rats in terms of magnitude and time course under the same experimental condition, procedure and paradigm for up to 180 min after a PDSI (Figs. 1E–G, 2E, and Fig. S2). However, the empathic mechanical pain hypersensitivity in mouse observers was maintained relatively longer in males than in females (Fig. 1G and Fig. S2). No sex difference was found in OCP between rat male and female observers during the whole time of observation (Fig. 2E).

Finally, because we had reported that the spontaneous pain-related behaviors in the demonstrators play a very important role in the elicitation of empathic responses in the observers [3], we also rated the total time that the distressed demonstrators spent on injured paw licking behaviors in mice and rats of both sexes (Fig. S3). The results showed no differences in pain indices between mouse and rat demonstrators of both sexes although female mice spent more time in paw licking than males (Fig. S3).

From the evolutionary point of view, empathy has been proposed to be hierarchical in mammals, evolving from a very low stage (motor mimicry and emotional contagion) to a relatively higher stage (empathic concern and consolation), and finally to the highest stage (perspective-taking, mentalizing, theory of mind, and targeted-help) from lower animals to human beings [6]. Although several emerging lines of evidence support the existence of emotional contagion in lower mammals [5, 10, 11], answers to questions of whether they are able to recognize, understand, share, and care for others are still controversial due to the lack of direct experimental evidence [3, 8, 12]. In a series of reports on empathy for pain in rats and mice, including the present study, we have provided strong experimental evidence for the existence of both emotional contagion and empathic consolation in laboratory rodents [1–5, 9]. Before our findings, empathic consolation had only been reported in a special sub-species of wild rodent—the socially monogamous, biparental prairie vole [8], although emotional contagion of pain or observational fear learning has been increasingly evidenced [5, 6, 10, 13]. Taken together, it has been demonstrated experimentally that lower mammals such as rodents exhibit both a lower stage (emotional contagion, i.e., OCP here) and a relatively higher stage of empathy (empathic concern and consolation), supporting the theoretical Russian-doll model for the evolution of empathy in mammals [6]. Moreover, the finding that social familiarity plays essential roles in the induction of empathy for pain in rodents also supports Darwin’s assertion that “with all animals, sympathy is directed solely towards the members of the same community, and therefore towards known, and more or less beloved members, but not to all the individuals of the same species” [5, 14].

In the past century, empathy has been mostly studied outdoors in non-human primates and other non-laboratory animals [6, 11]. Therefore, discovering, developing and validating laboratory animal models of empathy are critical for opening a new field of science—the neuroscience of empathy. Here, we have developed a laboratory rodent model of empathy for pain in both mice and rats using a set of novel behavioral parameters for both qualitative and quantitative assessment. We have identified and validated two behavioral components of empathy for pain in a laboratory rodent model: (1) consolation and (2) observational contagious pain.

To make qualitative and quantitative assessments of consolation, we successfully identified allolicking and allogrooming behaviors in naive observers during PDSIs with familiar conspecifics in pain. To determine whether the observer’s allolicking and allogrooming behaviors are selective or specific to the injury and pain of the object, we also evaluated general social behavior (allo-mouth and allo-tail sniffing) and non-social behavior (self-grooming) in the observers. In each type of targeted behavior, four parameters (latency, time course, total time, and visit count) were quantified. The results clearly showed that there were no species differences between mice and rats for allolicking and allogrooming behaviors in males or females, suggesting that laboratory rodents can be motivated to perform empathic consolation when witnessing their familiars in a painful or distressing condition. Mice and rats are likely as sharing and caring as humans. Our data showed that both mouse and rat observers began to approach a familiar conspecific in pain after a short delay when witnessing the event and then engaged longer in allolicking the injury site and allogrooming the body of the injured partner. In contrast, the same animals had a longer latency and a lower count in either self-grooming or allo-tail and allo-mouth sniffing, suggesting that laboratory rodents have a strong ability to rapidly recognize and understand the distressing condition of others. And this process is likely to motivate visiting, sharing, and caring for the injured object at the expense of loss of observers’ time in environmental exploration and self-grooming. Because self-grooming is predominant among the usual behaviors of rodents (> 40% of waking time) [7], the loss of time in self-grooming and gain of time in allolicking and allogrooming during PDSIs strongly imply the existence of prosocial and altruistic behaviors in rodent observers while witnessing a familiar in pain.

It is interesting to note that there was a sex difference between male and female mice in visit counts and total time of allolicking and allogrooming as well as allo-mouth and allo-tail sniffing; however, no such difference was seen in rats. Although the female mouse observers spent less time engaged in allogrooming but more time on allolicking toward the injury site in the distressed object, the sex difference in consolation in mice is not likely to be only caused by the sex difference in allogrooming, since general social behaviors (allo-mouth and allo-tail sniffing) also showed a sex difference. The sex difference in observer consolation in mice is not likely to be caused by a sex difference in the paw-licking behavior of injured demonstrators, because female observers engaged in less consolation toward the female demonstrators with more pain while male observers engaged in more consolation toward male demonstrators with less pain. Generally, the male has more consolation and more social behaviors than the female in mice. Moreover, rats spent equivalent amounts of time and visit counts in allolicking, allogrooming, and allo-tail sniffing in males and females. Unlike mice, the rat observers spent less time engaged in allo-mouth sniffing although there was no difference in the time spent allo-tail sniffing in the two species.

As noted above, although mice and rats have different sensitivity to mechanical stimuli, standardized measurements revealed no species and sex differences in OCP. Similar to our previous reports on male rats [2, 3], here the rat observers showed no sex difference in OCP between males and females after PDSIs with a familiar conspecific in pain. The paw withdrawal threshold of both sexes was lowered by > 50% immediately after a PDSI, and this lowered threshold remained unchanged until 300 min later. A relatively long-term decrease in mechanical threshold was identified on both sides of the hind paws and was in parallel between males and females in the rat observers. Similarly, OCP was also identified in mouse observers of both sexes immediately after a PDSI by showing leftward shift of the stimulus-response curves from baseline. This leftward shift remained unchanged between male and female mice until 240 min after the PDSI. Moreover, the intensity for the half maximal response in mice that is equivalent to the mechanical threshold in rats also showed a separation of the time effect between male and female at 240 min after the PDSI. Because the male observers had a longer time course in both the consolation and OCP than the females, this may reflect a stronger correlation between the two empathic behaviors in mice. Although sex differences in pain are well established [15], the sex difference in empathic contagious pain in mice is not likely due to a sex difference in mechanical pain sensitivity because the stimulus-response curves for the observers in the COnaive–CDnaive paradigm (for both pre- and post-PDSI) and the baseline of the COnaive–CDpain paradigm nicely overlapped between males and females.

In summary, our results demonstrated that both mice and rats have OCP and consolation when witnessing a conspecific in pain, although a sex difference may exist in mice. This further supports an evolutionary view of empathy—that social animals, including laboratory rodents, are gregarious in nature and may also have the ability to feel, recognize, understand, and share the distressed state of another.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to YQ Yu, W Sun, Y Wang, YJ Yin, RR Wang, Y Yang, and F Yang for cooperation and XL Wang for animal support. This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81571072 and 31600855).

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Footnotes

Rui Du and Wen-Jun Luo have contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Li Z, Lu YF, Li CL, Wang Y, Sun W, He T, et al. Social interaction with a cagemate in pain facilitates subsequent spinal nociception via activation of the medial prefrontal cortex in rats. Pain. 2014;155:1253–1261. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2014.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lü YF, Yang Y, Li CL, Wang Y, Li Z, Chen J. The locus coeruleus–norepinephrine system mediates empathy for pain through selective up-regulation of P2X3 receptor in dorsal root ganglia in rats. Front Neural Circuits. 2017;11:66. doi: 10.3389/fncir.2017.00066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li CL, Yu Y, He T, Wang RR, Geng KW, Du R, et al. Validating rat model of empathy for pain: effects of pain expressions in social partners. Front Behav Neurosci. 2018;12:242. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2018.00242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yu Y, Li CL, Du R, Chen J. Rat model of empathy for pain. Bio-protocol. 2019;9:e3266. doi: 10.21769/BioProtoc.3266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen J. Empathy for distress in humans and rodents. Neurosci Bull. 2018;34:216–236. doi: 10.1007/s12264-017-0135-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de Waal FBM, Preston SD. Mammalian empathy: behavioural manifestations and neural basis. Nat Rev Neurosci 2017, 18: 498–509. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Kalueff AV, Stewart AM, Song C, Berridge KC, Graybiel AM, Fentress JC. Neurobiology of rodent self-grooming and its value for translational neuroscience. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2016;17:45–59. doi: 10.1038/nrn.2015.8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burkett JP, Andari E, Johnson ZV, Curry DC, de Waal FB, Young LJ. Oxytocin-dependent consolation behavior in rodents. Science. 2016;351:375–378. doi: 10.1126/science.aac4785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lu YF, Ren B, Ling BF, Zhang J, Xu C, Li Z. Social interaction with a cagemate in pain increases allogrooming and induces pain hypersensitivity in the observer rats. Neurosci Lett. 2018;662:385–388. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2017.10.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mogil JS. Social modulation of and by pain in humans and rodents. Pain. 2015;156(Suppl 1):S35–S41. doi: 10.1097/01.j.pain.0000460341.62094.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Panksepp J, Panksepp JB. Toward a cross-species understanding of empathy. Trend Neurosci. 2013;36:489–496. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2013.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Langford DJ, de C Williams AC. The caring, sharing rat? Pain 2014, 155: 1183–1184. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Langford DJ, Crager SE, Shehzad Z, Smith SB, Sotocinal SG, Levenstadt JS, et al. Social modulation of pain as evidence for empathy in mice. Science. 2006;312:1967–1970. doi: 10.1126/science.1128322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Darwin C. The Descent of Man. 2. London: Penguin Group; 1871. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fillingim RB. Sex, Gender, and Pain. Seattle: IASP Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.