Abstract

This document addresses the current coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic for providers and patients in labor and delivery (L&D). The goals are to provide guidance regarding methods to appropriately screen and test pregnant patients for COVID-19 prior to, and at admission to L&D reduce risk of maternal and neonatal COVID-19 disease through minimizing hospital contact and appropriate isolation; and provide specific guidance for management of L&D of the COVID-19–positive woman, as well as the critically ill COVID-19–positive woman.

The first 5 sections deal with L&D issues in general, for all women, during the COVID-19 pandemic. These include Section 1: Appropriate screening, testing, and preparation of pregnant women for COVID-19 before visit and/or admission to L&D Section 2: Screening of patients coming to L&D triage; Section 3: General changes to routine L&D work flow; Section 4: Intrapartum care; Section 5: Postpartum care; Section 6 deals with special care for the COVID-19–positive or suspected pregnant woman in L&D and Section 7 deals with the COVID-19–positive/suspected woman who is critically ill. These are suggestions, which can be adapted to local needs and capabilities.

Key Words: coronavirus, COVID-19, obstetric protocol, pandemic

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is a global pandemic caused by a novel coronavirus called severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2. Currently, more than 100 million women are pregnant worldwide, and virtually all of them are at a risk of contracting COVID-19. Because pregnant women have a suppressed immune system, they may be at an increased risk of developing severe or critical disease associated with COVID-19, in particular pneumonia and respiratory failure. Early data from a meta-analysis of 41 pregnant women with COVID-19 showed that they may be at increased risk of miscarriage, preterm birth, preeclampsia, and cesarean delivery (CD), particularly if they are hospitalized with pneumonia.1 Their babies are at a higher risk of stillbirth (2.4%, 1/41), neonatal death (2.4%, 1/41), and admission to the intensive care unit.1 Asymptomatic women and women with mild disease have fewer complications. General guidance on the prevention and management of COVID-19 in pregnancy has been published.2, 3, 4, 5 In addition, maternal-fetal medicine guidance for COVID-19, with respect to outpatient prenatal care, has been recently published.6 It is currently estimated that more than one-third and up to two-thirds of the world population may be infected with COVID-19 virus.7, 8, 9 Many of the 145 million annual births worldwide are at risk, including about 400,000 babies born daily. This document addresses the current COVID-19 pandemic for providers and patients in labor and delivery (L&D). The goals are as follows:

-

●

To provide guidance regarding methods to appropriately screen and test pregnant patients for COVID-19 before, and at admission to L&D

-

●

To reduce the risk of maternal and neonatal COVID-19 disease through minimizing hospital contact and appropriate isolation

-

●

To provide specific guidance for management of L&D of COVID-19–positive and critically ill COVID-19–positive women

The first 5 sections deal with L&D issues in general, for all women, during the COVID-19 pandemic and are as follows: (1) appropriate screening, testing, and preparation of pregnant women for COVID-19 before visit and/or admission to L&D; (2) screening of patients coming to L&D triage; (3) general changes to routine L&D work flow; (4) intrapartum care; and (5) postpartum care. Section 6 deals with special care for COVID-19–positive or suspected pregnant women in L&D, and section 7 deals with COVID-19–positive women and women suspected of having COVID-19 who are critically ill.

These are suggestions that can be adapted to local needs and capabilities. Guidance is changing rapidly; therefore, one must continue to watch for updates. A website that is constantly being updated with COVID-19 pregnancy-specific guidance for both providers and patients is www.pregnancycovid19.com.

Section 1: Appropriate Screening, Testing, and Preparation of Pregnant Women for COVID-19 Before Visit and/or Admission to L&D

Suggested outpatient management of pregnant women with and without symptoms of COVID-19 has already been described.6 Inpatient management of pregnant women is similar to outpatient recommendations with regard to minimizing and eliminating all unnecessary contact of the patient with the hospital or birth center to optimize social distancing. In most cases, necessary patient-provider contacts should be made through telehealth or remotely, unless the patient describes an urgent problem.6

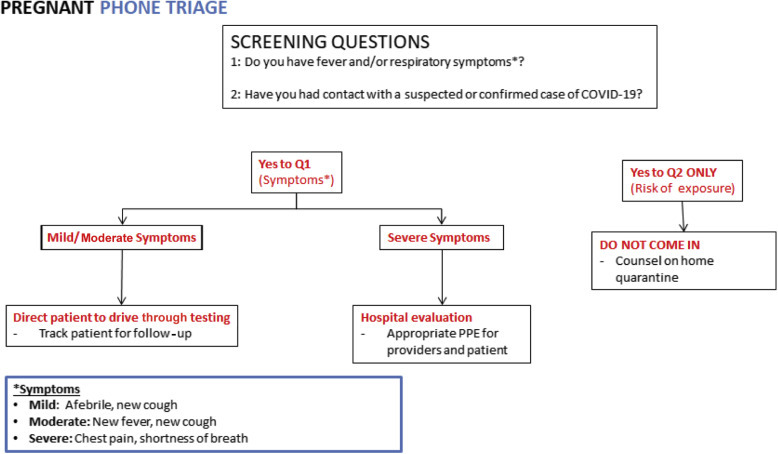

Phone calls to L&D should be triaged as shown in Figure 1 . Patients calling with symptoms of COVID-19 or influenza or with direct contacts who have no urgent obstetric issues should be referred for testing outside of the hospital as per local protocols, for example, through outside drive-through testing centers. Women without urgent obstetric issues awaiting results should stay at home to self-isolate. Those with urgent obstetric issues (eg, labor, rupture of membranes, vaginal bleeding), should be evaluated in an L&D area dedicated to patients with COVID-19. Providers should follow up on test results and notify the team of any positive test results.

Figure 1.

Flowchart for triaging patients who call into labor and delivery. COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; PPE, personal protective equipment

Boelig et al. Labor and delivery guidance for COVID-19. AJOG MFM 2020.

Labor presents a unique scenario in the COVID-19 pandemic, as all hospital admissions are anticipated and the timing of many admissions to the hospital is planned. In anticipation of hospital admission and to limit the risk of exposure, women should be instructed to discontinue work or begin working from home a minimum of 2 weeks before the anticipated date of delivery and to practice strict social isolation during this time. For most women, this should be initiated at about 37 weeks. In addition, L&D units should prepare simulations of the COVID-19 pandemic, including for donning personal protective equipment (PPE) and so on. They should appropriate designated rooms and operating rooms (ORs). For women with planned admissions for induction of labor or cesarean section, consider screening each individual and her birthing partner by a telephone call the day before admission.

Section 2: Screening of Patients Coming to L&D Triage

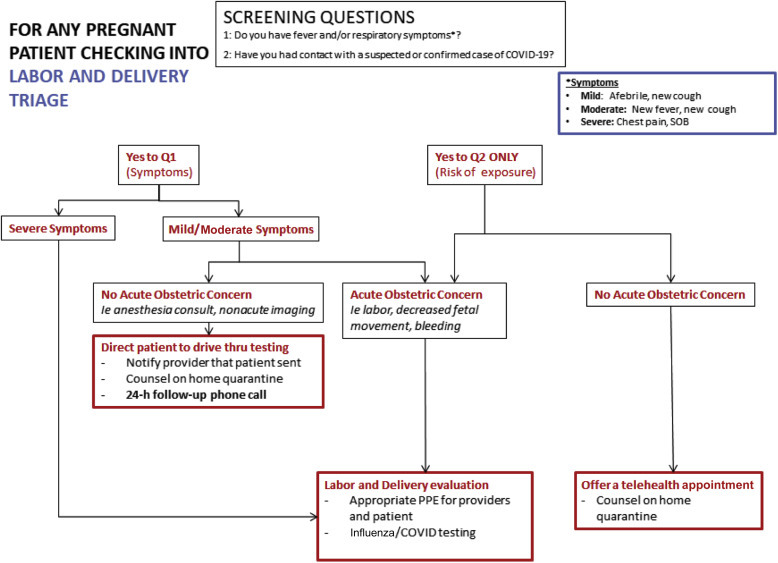

When women arrive at L&D, a designated staff member at the front of the unit (eg, patient access coordinator, unit coordinator) should verbally screen each individual for upper respiratory tract infection (URTI) symptoms. Any woman reporting fever, cough, or respiratory symptoms should be given a surgical mask and evaluated by a registered nurse or obstetric care provider. The recommended flow is presented in Figure 2 . All birthing partners should be verbally screened; if they screen positive, they should not be permitted to L&D and should be directed to appropriate testing or medical care as indicated. Where testing capacity allows, universal testing of all labor admissions should be performed due to the likely high rate of asymptomatic COVID-19–positive patients.10 If universal testing is not possible, a screening algorithm as in Figure 2 should be followed.

Figure 2.

Suggested flow for screening patients presenting to labor and delivery triage. COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; PPE, personal protective equipment

Boelig et al. Labor and delivery guidance for COVID-19. AJOG MFM 2020.

Important considerations in the care of patients who screen positive

Appropriate isolation and sanitation

-

•

All healthcare providers should be following the PPE recommendations by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) until COVID-19 has been ruled out.

-

•

Current CDC recommendations include the use of a surgical mask, protective eyewear, gown, and gloves. An N-95 mask should be utilized, if available, for any women with confirmed or suspected COVID-19.11

-

•

Aerosolization should in general be avoided because it increases the spread of the virus. If absolutely necessary, N-95 masks should be used in setting of aerosolization, including if patient is on bilevel positive airway pressure, has a tracheostomy, requires high-flow nasal cannula O2, or when administering nebulized medications. Second stage of labor is likely high risk for aerosolization, and N-95 mask should be used.12 , 13 The CDC has indicated that N-95 masks are as effective as powered air-purifying respirators and should be used for protection in the event of short-term exposure.11

-

•

Practice vigilant hand hygiene.

Management of patients who screen positive

-

•Acute complaint requiring evaluation (severe symptoms, labor complaint, etc.):

-

oA special room should be reserved as space allows for patients who screen positive (eg, URTI symptoms, fever), for both triage and labor.

-

o

-

•Scheduled CD or induction of labor:

-

oIdeally, this should be determined when screening the patient by phone the day before admission to avoid travel to the hospital (as suggested above).

-

oEvaluation should be conducted to determine if rescheduling in 2–3 days is feasible to allow for results of COVID-19 testing if necessary.

-

oFor COVID-19–positive patients with mild or moderate symptoms not requiring immediate care, it is important to recognize that the severity of disease peaks often in the second week; therefore, planning delivery before that time is optimal.

-

o

Section 3. General Changes to Routine L&D Work Flow

Respiratory precautions and PPE

Given the risk of asymptomatic carriers and transmission,10 it should be the goal of every unit that every patient wear a surgical mask and that every provider should have a surgical mask for each patient encounter.14 , 15 However, the ability to execute this recommendation is obviously limited by supply. For any patients with respiratory symptoms, full droplet precautions should be utilized, including the use of gloves, gown, and surgical mask with a face shield. N95 mask should be worn in addition to droplet precaution PPE for any patients with suspected or confirmed COVID, and for any patient, regardless of respiratory symptoms, during indispensable aerosol-generating procedures, including the second stage of labor.11 , 16 As much as possible, oxygen should not be given aerosolized. In addition, hand hygiene with alcohol-based handrub after every patient contact and appropriate donning and doffing of PPE are critical.11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17 Finally, rooms that are exposed need to be wiped down as respiratory viruses may spread from surface contact.18 These aggressive measures can help limit transmission in providers in a healthcare setting. Table 1 summarizes our recommendations.

Table 1.

Suggested PPE based on clinical situation

| Individual and clinical situation | Surgical mask | Droplet PPE (gown, gloves, surgical mask/face shield) | N-95 mask |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patient (with or without respiratory symptoms) | X | ||

| Provider during routine patient encounter | X | ||

| Provider during contact with patient with suspected or confirmed COVID-19 | X | X | |

| Provider caring for patient during aerosol-generating procedure including second stage of labor | X | X |

COVID, coronavirus disease 2019; PPE, personal protective equipment; URTI, upper respiratory tract infection.

Boelig et al. Labor and delivery guidance for COVID-19. AJOG MFM 2020.

Visitor policy

Given the significant risk of COVID-19 transmission between patients, families, and healthcare providers, there should be strict restrictions on visitor policy.

-

•L&D

-

oVisitation should be limited to 1 support person, in-person. Preference is for support through video, if patient agrees. All in-person support people should be screened as per Section 2. The support person should be easily identifiable by L&D staff; one suggestion would be to provide them with a special colored wrist band that must be worn at all times. Switching of visitors will not be permitted. Given the public health emergency, no additional in-person support people should be allowed, including doulas.

-

o

-

•Antepartum and postpartum

-

oThere should be a designated support person for the entire admission. This should be the same designated person as for delivery.

-

o

-

•Neonatal intensive care unit

-

oParents may visit in the neonatal ICU one at a time.

-

o

-

•

No children younger than 16–18 years will be permitted at any time.

-

•

Additional visitors for end-of-life situations may be considered and evaluated on a case-by-case basis.

Visitation may be further restricted at the discretion of unit leadership and as the outbreak evolves.

Patient admissions and location

In general, all efforts should be made to limit the movement of women from one care area to another (eg, triage room to antepartum room to L&D room). Admissions for delivery should remain on L&D; consider admitting stable admissions for antepartum monitoring directly to the antepartum unit. For example, consider holding a woman with preterm prelabor rupture of membranes in triage for continuous monitoring and observation for a longer period than what might typically occur, and then transferring her directly to the antepartum unit rather than moving her to an L&D room as an intermediary stop.

Pre-CD laboratory tests

To limit multiple visits to a healthcare setting, women should undergo routine preoperative laboratory tests (eg, complete blood cell count, type and screen) on the day of their CD.

Section 4: Intrapartum Care

Inductions of labor

Inductions of labor with medical indications in asymptomatic women should not be postponed or rescheduled. This includes inductions at 39 week of pregnancy, after patient counseling.19 However, in cases of extreme healthcare system burden (see Section 2), it may be appropriate to consider postponing or rescheduling the induction. This recommendation will vary depending on the current state of the COVID-19 pandemic. For example, in a region with early COVID-19 emergence, it may be prudent to proceed with delivery before high COVID-19 burden in the hospital. For sites with an existing high COVID-19 burden, an additional stay of 1–2 days in the hospital, occupying a hospital bed, for an induction of labor may not be possible. Other site-specific and COVID-19–specific considerations may include options such as beginning the induction process at home to limit in-hospital time (eg, outpatient Foley bulb cervical ripening). Induction can still be conducted as usual, with a combination of 60- to 80-mL single-balloon Foley for 12 hours and either oral 25-mcg misoprostol initially, followed by 25 mcg every 2–4 hours, or 50 mcg every 4–6 hours (if no more than 3 contractions per 10 minutes or previous uterine surgery), or oxytocin infusion.20 Outpatient Foley cervical ripening can be considered for low-risk women, to minimize contacts. CD should not be performed before 15 hours of oxytocin and amniotomy if feasible, and ideally after 18–24 hours of oxytocin.20

First stage

General guidance

Management of the first stage should not be altered, unless specified below. Intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis is recommended for group B Streptococcus–positive patients, immersion in water in the first stage of labor can be considered, oral restriction of fluid or solid food in the first stage of labor is not recommended, and oral administration of water and clear fluids can be encouraged as tolerated in labor. In case of oral restriction, intravenous fluid containing dextrose at a rate of 125 mL/h; given the significant risk of asymptomatic carriers especially in the absence of universal testing, there should be conscious use of fluids. Upright positions in the first stage of labor are recommended in women without regional anesthesia, women with regional anesthesia in the first stage can take whatever position they find most comfortable, and walking should be recommended in the first stage of labor in women without regional anesthesia, but in the delivery room. Women with regional anesthesia can walk or not walk in the first stage of labor; continuous bladder catheterization cannot be recommended in labor, and routine use of peanut ball cannot be recommended in labor because it has not been shown to be beneficial and may be a way to transmit infection. Oxytocin augmentation is recommended to shorten the time to delivery for women making slow progress in the first stage of spontaneous labor; higher doses of oxytocin can be considered; early intervention with oxytocin and amniotomy for the prevention and treatment of dysfunctional or slow labor is recommended; CD for arrest in the first stage of labor should not be performed unless labor has arrested for a minimum of 4 hours with adequate uterine activity, or 6 hours with inadequate uterine activity in a woman with rupture of membranes, adequate oxytocin, and ≥6-cm dilated cervix.20

Oxygen therapy

Although oxygen via nasal cannula is not considered an aerosol-generating procedure, the fact that nasal cannula or face mask are in contact with maternal respiratory tract and secretions makes handling of such equipment (taking on, taking off, or adjusting) can lead to a greater possibility of contamination or exposure between patient and provider. A recent meta-analysis has demonstrated that intrapartum oxygen has no fetal benefit and may cause harm.21 , 22 In the current scenario wherein reducing the risk of COVID-19 spread among healthcare providers and patient is paramount, there is even more reason to not utilize oxygen therapy for fetal resuscitation. Given the likely high rate of asymptomatic carriers,23 this principle applies regardless of patient’s COVID-19 status.

Nitrous oxide

The use of nitrous oxide involves risk of aerosolization and involves respiratory contamination. Eliminating nitrous oxide use during COVID-19 pandemic is recommended.24

Second stage

Management during the second stage of labor should not be altered, unless specified as in Section 6. See general and specific guidance for first stage, much of which applies to the second stage as well. Pushing should not be delayed because it prolongs time to delivery and increases chorioamnionitis and postpartum hemorrhage.25 , 26 Perineal massage27 and warm packs28 are each associated with decrease in third and fourth degree lacerations.

Third stage

There are concerns regarding limited resources for blood transfusion because of inability to run blood drives. Given this situation, all care should be taken to reduce the need for blood transfusion, including optimizing antenatal hemoglobin before delivery. In addition to standard oxytocin, consideration should be made for prophylactic tranexamic acid and misoprostol (400 mcg buccally).29 The use of cell-salvage during CD should be considered after stratification of risk for postpartum hemorrhage and institutional capabilities. If blood transfusion is indicated and hemorrhage is not ongoing, begin with transfusion of 1 unit rather than the typical 2 units of packed red blood cells, then reassess the clinical need for the second unit.

Some have advocated for avoiding delayed cord clamping, even if vertical transmission has not been confirmed at the time of the submission of this manuscript.

Anesthesia considerations

The Society for Obstetric Anesthesia and Perinatology has published interim guidelines based on expert opinion. As with other COVID-19 guidelines, these are rapidly evolving.24

-

•

Early epidural should be used to minimize need for general anesthesia in the event of emergent cesarean section.

-

•

COVID-19 is not a contraindication to neuraxial anesthesia.

-

•

Consider stopping nitrous oxide use due to potential risk of aerosolization.

Section 5: Postpartum Care

Women should be notified that they will be discharged in an expedited and safe fashion to limit the risk of infection to themselves, staff, and other patients.

Expedited discharge planning

-

•

All vaginal deliveries should have a goal of discharge on postpartum day 1, or even the same day if possible for selected women.

-

•

All CDs should have a goal of discharge on postoperative day 2, with consideration of postpartum day 1 discharge if meeting milestones.

-

•

Anticipated maternal discharge should be discussed with pediatrics/neonatology to determine timing of infant discharge.

-

•

Home care with supplies for blood pressure follow-up will be critical to expediting discharge of patients with a hypertensive disorder.

Postpartum visit

-

•

All postpartum visits, including wound checks, should be arranged for telehealth. Postpartum evaluation of cesarean wound healing or mastitis concerns may be optimized through the use of photo upload options available in many electronic medical record patient portal programs. Encourage either long-acting reversible contraceptive placement or Depo-Provera injection before discharge for patients planning to use these to eliminate need for additional in-person postpartum visits.

Section 6: Care for the Suspected or Confirmed COVID-19–Positive Pregnant Patient in L&D

Obstetric medications

Two commonly used medications in obstetrics have been the source of study and controversy in the setting of COVID-19 pandemic; nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), in particular indomethacin, are commonly used for tocolysis, and steroids, specifically betamethasone or dexamethasone, are used for fetal lung maturity. In addition, we will also address the use of magnesium, given the respiratory morbidity of COVID-19 (Table 2 ).

Table 2.

Use of common medications in preterm labor management for pregnant patients with COVID-19

| Gestational age |

<32 wk |

32–34 wk |

34–36 wk |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Respiratory symptom severity | Mild-moderate symptoms | Severe | Mild-moderate symptoms | Severe | Any |

| Steroids for fetal maturity | Use | Discuss risks and benefits with multidisciplinary team including ID, Pulmonary-Critical Care, Neonatology | Consider | Avoid | Avoid |

| Indomethacin | May consider if nifedipine not an option | Use nifedipine instead | Use nifedipine instead | Use nifedipine instead | Not indicated |

| Magnesium sulfate (neuroprotection) | Use | Discuss risks and benefits with multidisciplinary team including ID, Pulmonary-Critical Care, Neonatal-perinatal medicine | |||

Severe signs or symptoms include need for respiratory support, hypoxia, etc.

COVID, coronavirus disease 2019; ID, Infectious Disease.

Boelig et al. Labor and delivery guidance for COVID-19. AJOG MFM 2020.

Indomethacin

There were early reports postulating that NSAIDs may worsen the course of COVID-19. The virus binds to cells through the angiotensin-converting enzyme-2 (ACE-2) receptor; thus, it was postulated that NSAIDs, which increase ACE-2 expression, may result in worsening of the disease.30 However, this has not been substantiated, and multiple organizations, including the World Health Organization (WHO) and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) have advocated there should not be a restriction on NSAID use.31 In the setting of tocolysis, nifedipine may be considered as an alternative given the uncertainty regarding the impact of NSAIDs on COVID-19. These recommendations may change as additional data emerge.

Betamethasone/dexamethasone

The routine use of systemic corticosteroids in case of a viral pneumonia has been associated with increased morbidity.32 , 33 One study showed delayed viral clearance with the use of corticosteroids in those with Middle East respiratory syndrome.34 Specifically with COVID-19, there is an association between steroid use and mortality, although these studies do not control for baseline morbidity.35 , 36 Generally, steroid use evaluated in these studies is higher than a 2-day course of steroids; however, given the association between steroids and worsening morbidity of viral pneumonia and specifically COVID-19, judicial use of steroids for fetal lung maturity is recommended. It should be noted that the dose of steroids used for fetal lung maturity are lower than the systemic doses that have been used and studied in the setting of COVID-19 and other respiratory conditions. Consider Table 2 for steroid use for fetal lung maturity balancing benefit by risk of delivery within the next 7 days, gestational age, and potential risk based on maternal presentation. These recommendations are supported by the WHO.5

Magnesium sulfate

Magnesium sulfate is indicated for neuroprotection when delivery is anticipated <32 weeks or for eclampsia prophylaxis.37 , 38 There are no reported data regarding the impact of magnesium sulfate on COVID-19. However, given the potential respiratory complications with the use of magnesium sulfate, it should be used judiciously in case of severe respiratory symptoms with careful consideration of both total fluids administered and kidney function. Magnesium sulfate may be used as indicated in patients with mild or moderate symptoms.

Laboratory value changes

There are some changes noted with COVID-19 that have important implications in care for the pregnant patients. Specifically, COVID-19 may be associated with transaminitis, elevated creatinine, and thrombocytopenia.35 This is an important consideration in a patient presenting with a hypertensive disorder in assessing whether she has severe features of preeclampsia, hemolysis, elevated liver enzyme levels, and low platelet count syndrome, versus manifestation of COVID-19.

Intrapartum care

-

●Delivery timing

-

oCOVID-19 severity peaks in the second week; thus, it may be prudent to expedite delivery of term COVID-19–positive patients with only mild symptoms.

-

o

-

●Mode of delivery

-

oCOVID-19 alone is not an indication for a CD.

-

oDelivery mode should be dictated by obstetric indications.

-

o

- ●

-

●Precautions for transmission prevention

-

oDesignate nearby rooms, or a section of the floor to be used for suspected and confirmed COVID-19–positive patients

-

oRespiratory precautions

-

▪Room type: negative pressure room is not required.

-

▪If a patient has known COVID-19 or high suspicion for it, PPE should be used per hospital-specific guidelines. At a minimum, an N95 mask and full droplet precaution should be used by the providers in the room during the second stage of labor.

-

▪Minimize change in providers. Depending on the volume of COVID-19–positive patients, consider having a team designated for confirmed or suspected cases of COVID-19.

-

▪

-

o

-

●Medical care

-

oMultidisciplinary care coordination involving Maternal-Fetal Medicine, Infectious Disease, Pulmonary/Critical care, Obstetric anesthesia, and Neonatology

-

oConsult Maternal Fetal Medicine regarding the use of steroids for fetal maturity, indomethacin, and magnesium sulfate (Table 2).

-

oRefer to intrapartum oxygen use guideline. Given the lack of fetal benefit, and risk of contamination or transmission with the use of an intranasal device, we do not recommend the use of oxygen for fetal resuscitation in any patient, suspected case of COVID-19 or otherwise

-

oFluid restriction (total fluids <75 cc/h) unless there is concern for sepsis or hemodynamic instability

-

o

-

●CD

-

oDesignate, when possible, 1 OR for use for the suspected or confirmed COVID-19 patient and have appropriate PPE outside the OR door.

-

oA designated PPE monitor should be assigned to ensure proper donning and doffing of PPE.

-

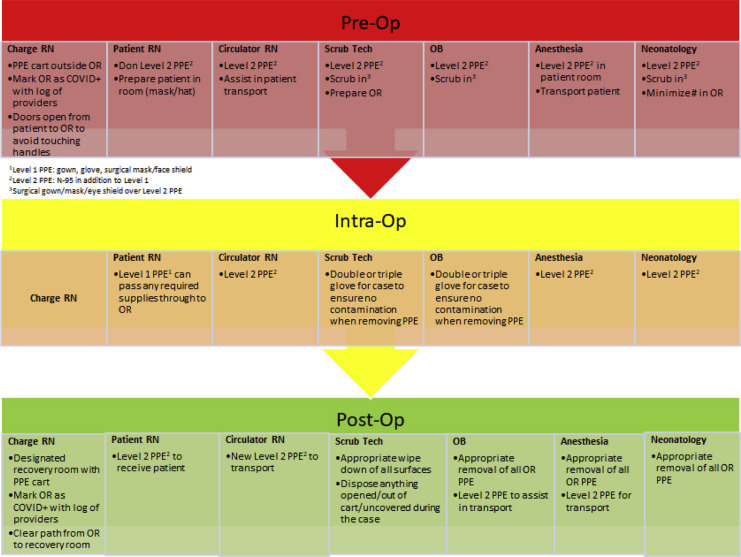

oAppropriate planning, including simulation training, should be done regarding planned, urgent, and emergent CD. Figure 3 presents a suggested flow to consider. Aspects to take into consideration include PPE placement in or near the OR to minimize time required for donning PPE in case of emergent CS, which providers will need additional PPE for direct patient contact, minimizing the number of providers involved in direct patient contact, etc.

-

o

Figure 3.

Flow chart for roles, equipment, and PPE in preparation for a cesarean delivery of COVID-positive patient

COVID, coronavirus disease; OB, obstetrician; OR, operating room; PPE, personal protective equipment; RN, registered nurse.

Boelig et al. Labor and delivery guidance for COVID-19. AJOG MFM 2020.

Postpartum care

-

●

Although breastfeeding is still encouraged (no evidence of COVID-19 transmission through breastmilk), given the risk of neonatal morbidity from transmission through maternal exposure, the CDC does recommend the separation of mother and neonate.

-

●Breastfeeding considerations

-

oBreast milk provision (by pumping) is encouraged and is a potentially important source of antibodies for the infant. The CDC recommends that during temporary separation, women who intend to breastfeed should be encouraged to express their breast milk to establish and maintain milk supply.

-

oBefore expressing breast milk, women should practice appropriate hygiene not just for hands but also for breasts before pumping.

-

oAfter pumping, all parts of the pump that come in contact with breast milk should be thoroughly washed, and the entire pump should be appropriately disinfected per the manufacturer’s instructions.

-

oExpressed breast milk should be fed to the newborn by a healthy caregiver.

-

oFor women and infants who are not separated, the CDC recommends that if a woman and newborn do room-in and the woman wishes to feed at the breast, she should put on a mask and practice hand hygiene before each feeding.41

-

o

-

●Pain control

-

oThe current FDA and WHO guidelines are not to restrict NSAID use. We support continued use of acetaminophen and ibuprofen for pain control and do not suggest increased narcotic use to replace ibuprofen or NSAIDs. These general recommendations may be modified depending on patient-specific morbidity and as we have more information regarding the association between NSAIDs and COVID-19 severity.31

-

o

Section 7: Care of the Critically Ill COVID-19 Pregnant Patient

All critically ill COVID-19 patients should be in isolation as per hospital protocol. PPE equipment should be outside the patient’s room or unit if it is a dedicated COVID-19 unit.

Fetal well-being

-

●

Corticosteroids: Given the potential risks of systemic steroids in COVID-19, steroids for fetal maturity should be used judiciously, balancing the benefit by gestational age with potential risks of worsening maternal morbidity. Decisions regarding the use of corticosteroids for fetal lung maturity should be made in concert with critical care team and neonatology.

-

●

For patients >24 weeks of pregnancy, electronic fetal monitoring for antenatal surveillance should be performed at least daily and with any change in maternal status if a CD at bedside is feasible. The fetus can be a “sixth” vital sign reflecting early deterioration in maternal status.

-

●

As per usual obstetric care, goal for saturations should be maintained >95%.

Maternal medical care

Special consideration should be given to normal maternal respiratory physiology and how this affects management of the acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS):

Pregnancy involves a natural respiratory alkalosis with a normal PCO2 of 28 to 32 mm Hg.42

Therapy for ARDS involves low tidal volumes and permissive hypercapnia (PCO2<60 mm Hg).43 Data on permissive hypercapnia in pregnancy are limited, but there do not appear to be adverse fetal affects.44

-

●

In the third trimester, increased positive end-expiratory pressures may be required.

-

●

Goal for blood pressure should be <160/110 mm Hg.

-

●

Patient should be positioned with left lateral tilt (if no other position is mandated for their treatment, eg, prone position) to relieve pressure from gravid uterus on venous return.

-

●

Prone positioning may be used as necessary with appropriate support of gravid abdomen.

Delivery planning

-

●Preparation

-

oEquipment for an emergent CD should be available at the bedside, including neonatal equipment.

-

oA hemorrhage kit, which includes Methergine, Hemabate, and misoprostol, should be at the bedside. Tranexamic acid needs to be refrigerated but should be requested for all deliveries and readily available in the ICU.

-

oThe use of terbutaline should be reviewed with the critical care team, depending on the patient’s clinical status owing to risk of tachycardia

-

oAn effective method of communication for the anesthesia team, neonatology team and obstetric team should be implemented.

-

oIf an emergent delivery is planned, this should be performed at the bedside in the ICU to avoid transferring the patient.

-

o

-

●Timing

-

oConsideration should be given to delivery >34 weeks for the critically ill pregnant patient. Delivery can help optimize maternal respiratory status. This should be balanced with the potential risk of catecholamine surge, autotransfusion, and fluid shifts that could potentially exacerbate maternal condition.

-

o

-

●Intrapartum care

-

oIf a critically ill pregnant patient at term goes into labor, the aforementioned precautions should be initiated.

-

oAn assisted second stage of labor is likely to be necessary.

-

oA dedicated obstetrician should be assigned to the patient with minimal change in providers, as the situation allows.

-

oThe neonatology team should be present at the time of delivery, and the infant should be placed in isolation after delivery, given the unknown risks of transmission.

-

oPrevention of postpartum hemorrhage should occur as detailed above.

-

o

Postpartum care

-

●

The infant should be separated as soon as possible and transferred to an isolation room appropriately.

-

●

The use of a breast pump is encouraged, after review of maternal medications (see Section 6).

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the help of other members of the MFM Division and Ob-Gyn Department at the Thomas Jefferson University, including Jason Baxter, Amanda Roman, Huda Al-Kouatly, Rebekah McCurdy, Johanna Quist-Nelson, Emily Rosenthal, Becca Pierce-Williams, Leen Al-Hafez, Laura Felder, Lauren Johnson, Gina Gardigan, and William Schlaff.

Footnotes

Dr Boelig was supported by a PhRMA Foundation Faculty Development Award in Clinical and Translational Pharmacology.

The authors report no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Di Mascio D., Khalil A., Saccone G., et al. Outcome of coronavirus spectrum infections (SARS, MERS, COVID-19) during pregnancy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM. 2020;2:100107. doi: 10.1016/j.ajogmf.2020.100107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.The Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine (SMFM) Dotters-Katz S., Hughes B.L. Coronavirus (COVID-19) and pregnancy: what maternal-fetal medicine subspecialists need to know. https://s3.amazonaws.com/cdn.smfm.org/media/2267/COVID19-_updated_3-17-20_PDF.pdf Available at:

- 3.American College of Obstetricians & Gynecologists Practice advisory. Novel coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) https://www.acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance/practice-advisory/articles/2020/03/novel-coronavirus-2019 Available at:

- 4.Royal College of Obstetricians & Gynaecologists Coronavirus (COVID-19) infection in pregnancy. Information for healthcare professionals. https://www.rcog.org.uk/globalassets/documents/guidelines/2020-03-21-covid19-pregnancy-guidance-2118.pdf Version 4: Available at: Published March 21, 2020. Accessed March 23, 2020.

- 5.World Health Organization Clinical management of severe acute respiratory infection when noval coronavirus (nCoV) infection is suspected. Interim guidance. https://www.who.int/publications-detail/clinical-management-of-severe-acute-respiratory-infection-when-novel-coronavirus-(ncov)-infection-is-suspected Available at:

- 6.Boelig R.C., Saccone G., Bellussi F., Berghella V. MFM guidance for COVID-19. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM. 2020;2:100106. doi: 10.1016/j.ajogmf.2020.100106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Daily Sabah Coronavirus may affect two-thirds of world population, specialist says. https://www.dailysabah.com/health/2020/02/13/coronavirus-may-affect-two-thirds-of-world-population-specialist-says Available at: Accessed March 24, 2020.

- 8.Ma J., Lew L., Jeong-ho L. A third of coronavirus cases may be ‘silent carriers’, classified Chinese data suggests. https://www.scmp.com/news/china/society/article/3076323/third-coronavirus-cases-may-be-silent-carriers-classified Available at: Accessed March 24, 2020.

- 9.Bloomberg. Research Covid-19 could infect two-thirds of globe. https://www.nst.com.my/world/world/2020/02/565515/research-covid-19-could-infect-two-thirds-globe Available at: Accessed March 24, 2020.

- 10.Breslin N., Baptiste C., Gyamfi-Bannerman C., et al. Coronavirus disease 2019 infection among asymptomatic and symptomatic pregnant women: two weeks of confirmed presentations to an affiliated pair of New York City hospitals. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM. 2020;2:100118. doi: 10.1016/j.ajogmf.2020.100118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Interim infection prevention and control recommendations for patients with suspected or confirmed coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in healthcare settings. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/infection-control/control-recommendations.html Available at:

- 12.Brosseau L. “Commentary: COVID-19 transmission messages should hinge on science.” Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy, University of Minnesota. http://www.cidrap.umn.edu/news-perspective/2020/03/commentary-covid-19-transmission-messages-should-hinge-science Available at:

- 13.Milton D.K., Fabian M.P., Cowling B.J., Grantham M.L., McDevitt J.J. Influenza virus aerosols in human exhaled breath: particle size, culturability, and effect of surgical masks. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9:e1003205. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wax R.S., Christian M.D. Practical recommendations for critical care and anesthesiology teams caring for novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) patients. Can J Anesth. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s12630-020-01591-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.MacIntyre C.R., Chughtai A.A. Facemasks for the prevention of infection in healthcare and community settings. BMJ. 2015;350:h694. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baud D., Giannoni E., Pomar L., et al. COVID-19 in pregnant women. Authors’ reply. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30192-4. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention What healthcare personnel should know about caring for patients with confirmed of possible COVID-19 infection. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/caring-for-patients.html Available at:

- 18.Otter J.A., Donskey C., Yezli S., Douthwaite S., Goldenberg S.D., Weber D.J. Transmission of SARS and MERS coronaviruses and influenza virus in healthcare settings: the possible role of dry surface contamination. J Hosp Infect. 2016;92:235–250. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2015.08.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Berghella V., Al-Hafez L., Bellussi F. Induction for 39 weeks’ gestation: let’s call it what it is! Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM. 2020;2:100098. doi: 10.1016/j.ajogmf.2020.100098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Berghella V, Bellussi F, Schoen CN. Evidence-based labor management: induction of labor (part 2). Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM [In press]. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Hamel M.S., Anderson B.L., Rouse D.J. Oxygen for intrauterine resuscitation: of unproved benefit and potentially harmful. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;211:124–127. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2014.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Raghuraman N., Wan L., Temming L.A., et al. Effect of oxygen vs room air on intrauterine fetal resuscitation: a randomized noninferiority clinical trial. JAMA Pediatr. 2018;172:818–823. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.1208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bai Y, Yao L, Wei T, et al. Presumed asymptomatic carrier transmission of COVID-19. JAMA 2020 [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.The Society for Obstetric Anesthesia and Perinatology Interim considerations for obstetric anesthesia care related to COVID19. https://soap.org/education/provider-education/expert-summaries/interim-considerations-for-obstetric-anesthesia-care-related-to-covid19/ Available at:

- 25.Cahill A.G., Srinivas S.K., Tita A.T.N., et al. Effect of immediate vs delayed pushing on rates of spontaneous vaginal delivery among nulliparous women receiving neuraxial analgesia: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2018;320:1444–1454. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.13986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Di Mascio D., Saccone G., Bellussi F., et al. Delayed versus immediate pushing in the second stage of labor in women with neuraxial analgesia: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2020.02.002. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aquino C.I., Guida M., Saccone G., et al. Perineal massage during labor: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2020;33:1051–1063. doi: 10.1080/14767058.2018.1512574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Magoga G., Saccone G., Al-Kouatly H.B., et al. Warm perineal compresses during the second stage of labor for reducing perineal trauma: a meta-analysis. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2019;240:93–98. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2019.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gallos I.D., Williams H.M., Price M.J., et al. Uterotonic agents for preventing postpartum haemorrhage: a network meta-analysis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;4:CD011689. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD011689.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fang L., Karakiulakis G., Roth M. Are patients with hypertension and diabetes mellitus at increased risk for COVID-19 infection? Lancet Respir Med. 2020 doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30116-8. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.U.S. Food and Drug Administration FDA advises patients on use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) for COVID-19. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/fda-advises-patients-use-non-steroidal-anti-inflammatory-drugs-nsaids-covid-19 Available at:

- 32.Lansbury L., Rodrigo C., Leonardi-Bee J., Nguyen-Van-Tam J., Lim W.S. Corticosteroids as adjunctive therapy in the treatment of influenza. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;2:CD010406. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD010406.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Delaney J.W., Pinto R., Long J., et al. The influence of corticosteroid treatment on the outcome of influenza A(H1N1pdm09)-related critical illness. Crit Care. 2016;20:75. doi: 10.1186/s13054-016-1230-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Arabi Y.M., Mandourah Y., Al-Hameed F., et al. Corticosteroid therapy for critically ill patients with Middle East respiratory syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018;197:757–767. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201706-1172OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Guan W.J., Ni Z.Y., Hu Y., et al. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhou F., Yu T., Du R., et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective study. Lancet. 2020 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Obstetric Practice; Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine Committee opinion no. 455: magnesium sulfate before anticipated preterm birth for neuroprotection. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;115:669–671. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181d4ffa5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.American College of Obstetricians & Gynecologists ACOG practice bulletin no. 202: gestational hypertension and preeclampsia. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133:e1–e25. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen H., Guo J., Wang C., et al. Clinical characteristics and intrauterine vertical transmission potential of COVID-19 infection in nine pregnant women: a retrospective review of medical records. Lancet. 2020;395:809–815. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30360-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhu H., Wang L., Fang C., et al. Clinical analysis of 10 neonates born to mothers with 2019-nCoV pneumonia. Transl Pediatr. 2020;9:51–60. doi: 10.21037/tp.2020.02.06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Pregnancy & breastfeeding. Information about coronavirus disease 2019. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/prepare/pregnancy-breastfeeding.html Available at:

- 42.Lim V.S., Katz A.I., Lindheimer M.D. Acid-base regulation in pregnancy. Am J Physiol. 1976;231:1764–1769. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1976.231.6.1764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fuchs H., Rossmann N., Schmid M.B., et al. Permissive hypercapnia for severe acute respiratory distress syndrome in immunocompromised children: a single center experience. PLoS One. 2017;12 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0179974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pacheco L.D., Saad A. Critical care obstetrics. 6th ed. Wiley-Blackwell; Hoboken, NJ: 2018. Chapter 13: Ventilator management in critical illness. [Google Scholar]