Abstract

Aim

To investigate the new risk factors for keloid recurrence after postoperative electron beam radiotherapy (RT) and evaluate the effectiveness of tranilast in combination with electron beam RT by comparing the local control rate.

Background

Identifying patients at high risk of recurrence after postoperative RT for keloids remains a challenge. Besides, no study examined the effectiveness of tranilast in combination with RT after surgery for the prevention of keloids recurrence.

Materials and Methods

This study included 75 lesions in 59 consecutive patients who had undergone postoperative RT at our institute. The follow-up period and prescription of tranilast were examined beside several potential risk factors, such as multiple lesions, size, and shape.

Results

The median follow-up was 72 months (range, 6–147 months). Twenty-one lesions in 17 patients recurred in a median of 12 months after treatment (range, 1–60 months). Local control rates of all 75 lesions were estimated as 93%, 78%, 70%, and 68% at 1, 2, 5, and 10 years. Multiple lesions constituted a significant risk of recurrence (P = 0.03). A larger long axis was significantly related to the recurrence (P < 0.01). Irregular shape was associated with a significantly worse local control rate (P = 0.02). There was no significant difference in the local control rate between patients receiving tranilast and those who did not (P = 0.52).

Conclusions

Multiple lesions and irregular shape were risk factors of keloid recurrence after postoperative electron beam RT. The effectiveness of tranilast was not demonstrated in the study.

Keywords: keloid, hypertrophic scar, radiation, tranilast

1. Introduction

The efficacy and safety of radiation therapy (RT) following surgical excision for keloids are well documented in literature.1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16 More recent studies have reported that the recurrence rate is approximately 10–20% or less after RT following surgical excision.15, 16, 17, 18 Despite several reports about risk factors of recurrence,1, 2, 3, 4,9,10,19 identifying patients at high risk of recurrence after postoperative RT with surgery for keloids remains a challenge.

The studies so far have revealed that the risk factors of recurrence include large lesion,1, 2, 3, 4 lesions that developed in site with high stretch tensions,1,3 history of previous treatment for the lesions,3,4 family history of keloids,2 and lesions resulting from burns3 or complicated by infection.2 In contrast, ethnicity2,4 and individual keloid history2 may not be risk factors. Age,1, 2, 3 gender,1,3,4 and interval time from surgery to RT1,3,4 have remained to be controversial risk factors. There is a report that revealed that surgery methods may be associated with local control after RT following surgical excision.1

Meanwhile, no report was found that referred to the relationship between preoperative pain or pruritus and keloid recurrence after RT with surgery. Keloid has been described as a result of chronic inflammation.20 Pain and pruritus are symptoms of local inflammation, and the presence or absence of pain or pruritus before treatment may be related to keloid recurrence. Moreover, there is no study that investigated the relationship between hypertension and keloid recurrence after surgery followed by RT, although high blood pressure has been suggested to be involved in the local keloid severity.21

Regarding prevention of keloid recurrence, tranilast (Rizaben®) is approved in some countries including Japan and Korea.22 Tranilast suppresses collagen synthesis in fibroblast by downregulating transforming growth factor beta 1.23 Tranilast has been reported to show a significantly better symptom improvement than heparinoid in a double-blind comparative study.24 However, there is no study that investigated the efficacy of the combined use of RT and tranilast after surgery for the prevention of keloid recurrence.

This study aimed to examine the local control rate of keloid after electron beam RT following surgery and investigate new risk factors for keloid recurrence after the therapy, and to assess the effectiveness of tranilast in combined treatment with electron beam RT for the prevention of keloid recurrence.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients

A total of 85 lesions of clinically diagnosed keloid or hypertrophic scar in 67 patients were treated with electron beam RT following surgical excision at our institute between 2006 and 2017. The indication for postoperative RT was determined for each case by plastic surgeons. Medical records were reviewed, and patients were asked to answer questions about recurrence or late adverse events by phone call. A follow-up period shorter than 6 months was considered as the exclusion criterion. According to this criterion, 10 lesions in 9 patients were excluded from the study. There was one patient with 2 lesions, with one lesion being followed up for more than 6 months and the other being followed up for less than 6 months. Consequently, this study included 75 lesions in 59 patients. The sites of the 75 lesions were as follows: earlobe (n = 35), chest wall (n = 11), shoulder (n = 10), abdomen (midline, n = 3; others, n = 7), face (n = 5), suprapubic region (n = 2), upper arm (n = 1), and back (n = 1).

Gender, age, whether having single or multiple (≥ 2) keloid lesions, family history of keloids or hypertrophic scar, and presence or absence of hypertension were examined as the characteristics of the patients. Patients were considered to have hypertension when they were prescribed with antihypertensive drugs. The number of patients with the abovementioned characteristics is shown in Table 1, with the local control rates presented in the Results section.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics and local control rate.

| Local control rate |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Category (n) | 1 year (%) | 2 years (%) | 5 years (%) | 10 years (%) |

P-value |

| First treated lesion in the patient (59) | 91 | 78 | 69 | 66 | |

| Gender | |||||

| Male (24) | 88 | 62 | 62 | 56 | 0.11 |

| Female (35) | 94 | 88 | 73 | 73 | |

| Family history | |||||

| Yes (11) | 82 | 70 | 47 | 47 | 0.19 |

| No (44) | 93 | 88 | 73 | 69 | |

| Keloid lesions | |||||

| Single (26) | 92 | 88 | 83 | 83 | 0.03 |

| Multiple (30) | 90 | 68 | 54 | 50 | |

| Hypertension | |||||

| Yes (8) | 100 | 86 | 86 | 64 | 0.72 |

| No (51) | 90 | 76 | 66 | 66 | |

Family history in 4 patients and whether having single or multiple lesions in 3 patients were not assessed because the patients could not be contacted by phone call and the records were inadequate.

The definition of recurrence was as follows: (1) when the patient answered that the keloid or hypertrophic scar had relapsed or (2) when the plastic surgeon examined the lesion and found out that the lesion became larger than before the surgical excision.

This retrospective study was approved by the ethics board of our institute (approval number, 2018–30 and 2018–40). The need for informed consent was waived, and opt-out was implemented. The study procedures were performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

2.2. Keloid lesions

The following were investigated as features of the lesions; length of the longest axis, site, etiology, age of onset, regular or irregular in shape, presence of pain or pruritus, history of previous surgery for the keloid or hypertrophic scar, and the presence or absence of tranilast prescription and the length of time that tranilast was prescribed after postoperative RT. Table 2 shows the number of lesions classified based on the characteristics, with the local control rates presented in the Results section.

Table 2.

Lesion characteristics and local control rate.

| Local control rate |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Category (n) | 1 year (%) | 2 years (%) | 5 years (%) | 10 years (%) | P-value |

| All lesions (75) | 93 | 78 | 70 | 68 | |

| Longest axisa, cm | |||||

| < 4.3 (54) | 94 | 84 | 75 | 75 | 0.03 |

| ≥ 4.3 (19) | 89 | 61 | 52 | 42 | |

| Site | |||||

| High stretch tension (24) | 92 | 78 | 72 | 66 | 0.91 |

| Low stretch tension (51) | 94 | 79 | 68 | 68 | |

| Earlobe keloid | |||||

| Yes (35) | 100 | 86 | 76 | 76 | 0.13 |

| No (40) | 87 | 71 | 64 | 60 | |

| Etiologyb | |||||

| Large scar (30) | 93 | 87 | 78 | 73 | 0.30 |

| Small scar (45) | 93 | 72 | 63 | 63 | |

| Age of onset, years | |||||

| ≤ 29 (48) | 92 | 77 | 66 | 66 | 0.29 |

| ≥ 30 (25) | 96 | 88 | 83 | 76 | |

| Shape | |||||

| Regular (36) | 97 | 94 | 80 | 80 | 0.02 |

| Irregular (37) | 89 | 63 | 59 | 54 | |

| Pain or pruritus before treatment | |||||

| Yes (44) | 98 | 79 | 66 | 63 | 0.83 |

| No (15) | 80 | 66 | 66 | 66 | |

| History of previous surgery for the lesion | |||||

| Yes (34) | 100 | 94 | 83 | 83 | 0.03 |

| No (36) | 86 | 67 | 64 | 59 | |

| Total radiation dose | |||||

| 15 Gy (61) or 10 Gy (1) | 94 | 77 | 69 | 66 | 0.64 |

| 20 Gy (13) | 92 | 85 | 74 | 74 | |

| Interval day from surgery to RT, day | |||||

| 0 (35) | 90 | 78 | 69 | 63 | 0.64 |

| ≥ 1c (40) | 95 | 79 | 70 | 70 | |

| Tranilast prescription | |||||

| Yes (62) | 92 | 78 | 68 | 65 | 0.52 |

| No (10) | 100 | 78 | 78 | 78 | |

RT = radiotherapy.

The total number of lesions in some categories may not be 75 due to lack of data.

The cutoff value was determined as 4.3 cm, which was an approximation of the mean of the recurred lesions.

Large scar includes surgical wound, while small scar includes piecing, insect bite, or acne. No lesion was derived from burns.

Among the 40 lesions in this group, 38 lesions were treated with RT the next day of the surgical excision. One of the remaining two lesions received RT 6 days later and the other 10 days after surgery considering the patient’s circumstances.

The median length of the longest axis was 2.4 cm (range, 0.8–18 cm). The recurred lesions had significantly longer diameter (mean, 4.24 cm; 95% CI, 3.3–5.2) than nonrecurred lesions (mean, 2.67 cm; 95% CI, 2.0–3.3) (P < 0.01). The lesions were divided into two groups based on the length of the longest axis of 4.3 cm, the approximate mean diameter of the long axis of recurred lesions.

The chest wall, shoulder, and abdominal midline were classified as sites with high stretch tension, while other sites were classified as sites with low stretch tension. The shape of the lesion was evaluated in accordance with the Japan Scar Workshop Scar Scale 2011 (please see http://www.scar-keloid.com/pdf/JSW_scar_scale_2011_EN.pdf25) or 2015.26 The etiology consisted of either a large or small scar.

2.3. Radiotherapy and tranilast prescription

Electron beam RT was performed using Monaco version 5.11 (Elekta AB, Stockholm), Eclipse version 7.3.10 (Varian Medical Systems, California), or Pinnacle3 version 9.10 (Philips, Amsterdam). Energy and depth of dose prescription were adjusted for each case to achieve optimal dose distribution. The 4 MeV electron beam was administered to 15 lesions, 6 MeV was administered to 42 lesions, and 9 MeV was administered to 18 lesions. RT was performed using Versa HD (Elekta AB) or Clinac 21EX (Varian Medical Systems). To improve the surface dose, 0.5 cm bolus was used in 54 lesions, while the bolus was not used in 21 lesions without enough space.

RT was usually started on the day of surgery or the next day. RT regimens of a total of 15 or 20 Gy in 5 Gy per fraction were used in most cases. Irradiation was delivered daily. A total regimen of 20 Gy was administered in lesions that seemed likely to recur on the consensus made by the treating radiation oncologist and plastic surgeon. A regimen of 10 Gy in 1 fraction was administered to one lesion according to the patient’s request.

As prophylactic treatment after RT following surgical excision, tranilast was orally administered 100 mg three times a day, every day. The prescription period varied from case to case depending on the plastic surgeon’s discretion. Tape fixation, local injection, and ointment use after postoperative RT were not evaluated in this study because their accurate survey was difficult.

2.4. Statistical analyses

The Student’s t-test was used for the analysis of continuous variables. The chi-squared test and Fisher’s exact test for discrete variables were used to compare proportions. The Kaplan-Meier method was used to estimate local control rates. The log-rank test was used to compare local control rates between groups. P-values of < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using JMP version 12.0.1 software (SAS Institute, North Carolina).

In order to reduce the influence of bias, analyses were performed with the lesion first treated in the patients (59 lesions in 59 patients) in the categories of gender, family history, keloid lesions, and hypertension. In the remaining categories, analyses were performed with all the lesions (75 lesions in 59 patients).

3. Results

3.1. Patients’ characteristics and local control rate

Fifty-nine patients with a median age of 28 years (ranging from 11 to 90 years) were included in this study. The age at initial RT course was adopted for patients who underwent more than 2 courses of RT. The median follow-up period was 72 months (range, 6–147 months). Twenty-one lesions in 17 patients recurred in a median of 12 months after electron beam RT following surgical excision (range, 1–60 months). No patient suffered from late adverse events including cancer development.

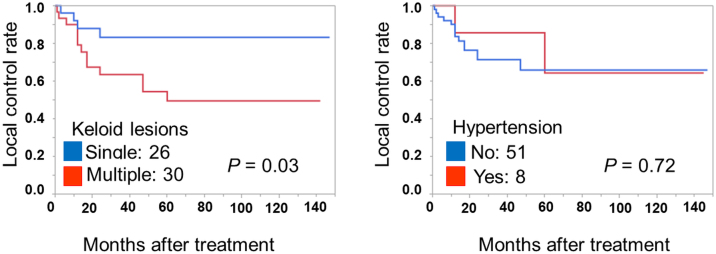

Table 1 shows patient characteristics and local control rates, and Fig. 1 presents a part of the results in Table 1. Of the lesions first treated in the patients (59 lesions in 59 patients), 1-year, 2-year, 5-year, and 10-year local control rates were 91%, 78%, 69%, and 66%, respectively.

Fig. 1.

Kaplan-Meier curves of local control rate in patients with single or multiple keloid lesions and in patients with or without hypertension.

Local control rate of lesions in patients with multiple lesions was significantly worse than those in patients with single lesion (P = 0.03) (Fig. 1). The patients with multiple lesions had family history at significantly higher rate than patients with a single lesion (10 of 29 vs. 1 of 25, P < 0.01).

The mean age of patients with hypertension (67 years, 95% confidence interval [CI], 57.5–78.0) was significantly higher than patients without hypertension (30 years, 95% CI, 26.8–35.0) (P < 0.01). There was no significant difference in local control rates between patients with or without hypertension.

3.2. Lesions’ characteristics and local control rates

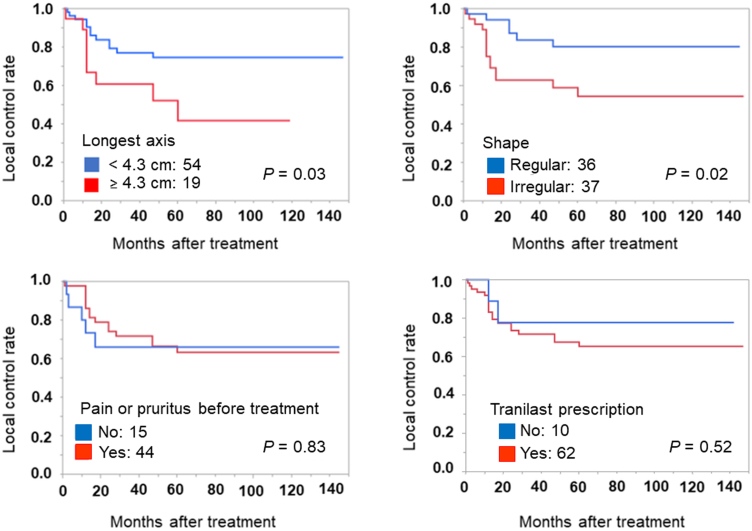

Table 2 shows the lesion characteristics and local control rates, and Fig. 2 presents a part of the results in Table 2. The local control rates of all 75 lesions were estimated as 93%, 78%, 70%, and 68% at 1 year, 2 years, 5 years, and 10 years, respectively. Pathologically, 29 lesions were diagnosed with keloid (n = 26) or hypertrophic scar (n = 3). The remaining lesions were clinically diagnosed. There was no lesion that was clinically diagnosed as keloid or hypertrophic scar but was pathologically denied.

Fig. 2.

Kaplan-Meier curves of local control rate by lesion characteristics.

Lesions with the longest axis < 4.3 cm had significantly better local control rate than lesions with longest axis ≥ 4.3 cm (P = 0.03). There was no significant difference in local control rate between the site with high and low stretch tension. The lesions at the high stretch site were more likely to receive a total of 20 Gy (33%, 8/24) irradiation dose than lesions at the low stretch site (10%, 5/51) (P = 0.01). When classified by earlobe (6%, 2/35) or non-earlobe keloids (28%, 11/40), there was a significant difference in the proportion of lesions that received a total of 20 Gy irradiation dose as well (P = 0.01).

Regarding shape, both regular and irregular occupied about a half. Irregular shape was significantly related to keloid recurrence (P = 0.02). Almost half of the lesions had received surgery before, and the history of previous surgery for the lesions was significantly related to good local control rate (P = 0.03). Patients with earlobe keloid had a history of previous surgery for the lesion at a significantly higher rate (78%, 25/32) than patients with non-earlobe keloid (24%, 9/38) (P < 0.01).

Total radiation dose and interval day from surgery to RT (the same day or the next day) were not significantly related to local control rate after treatment. A patient with earlobe keloid who underwent RT of 10 Gy in 1 fraction did not have local recurrence during the 6-month follow-up period. A patient who underwent RT 6 days after the surgery for earlobe keloid had no recurrence during the 16-month follow-up period, while a patient who underwent RT 10 days after the surgery for a chest wall lesion had local recurrence at 47 months after treatment.

The median duration of tranilast prescription was 4 months (range, 1–12 months) for 62 patients who were prescribed tranilast. There was no significant difference in the local control rate with or without tranilast prescription.

Fig. 1, Fig. 2 show the Kaplan-Meier curves of local control rate from univariate analyses. Evaluation of hazard ratio with multivariate analysis was not performed in this study because there were only 21 cases of recurrence, and spoiling reliability by overfitting was a concern.

4. Discussion

This study investigated the risk factors for keloid recurrence after electron beam RT following surgical excision and assessed the effectiveness of tranilast in combined treatment with electron beam RT after surgery. Multiple keloid lesions and irregular shape were found to be significant risk factors of recurrence. The length of the longest axis was confirmed to correlate with keloid recurrence. The lack of previous surgery for keloid lesions was associated with a significant worse local control rate contrary to past reports. Pain or pruritus before treatment, complication of hypertension, and tranilast prescription were newly evaluated in this study whether these were risk factors for keloid recurrence; however, these were not significant in predicting keloid recurrence after postoperative electron beam RT.

Local control rate of all lesions gradually declined by unit of year in this study as reported by other studies.1, 2, 3,9 Multiple lesions were found to be related to a significantly worse local control rate in the current study unlike in the past report.2 Meanwhile, family history did not show a significant relationship between the local control rate contrary to the past study.2 However, the number of patients with family history of keloid was only 11 in the current study; moreover, local control rate from 2 to 10 years in patients with family history of keloid was worse by as much as about 20% than that in the patients without family history of keloids. Furthermore, family history was significantly related to multiple lesions. Taken together, family history might have been a significant risk factor if investigated with a large number of patients.

Male patients had a tendency for worse prognosis, congruent with the findings of other studies,1,4 though the difference was not significant. The relationship between hypertension and keloid local control after RT with surgery was newly investigated in this study. In the general population, hypertension is not common among young patients, and patients with keloids are often young. The trend was the same for this study cohort. In this regard, the association of hypertension and keloid recurrence may have not been fully assessed in our study. Investigation with a large number of cases including older patients, therefore, would be necessary to prove the relationship between hypertension and keloid recurrence.

As in the past studies,1, 2, 3, 4 the size of the recurred lesions after treatment was larger than nonrecurred lesions. Additionally, irregular shape was significantly related to the worse local control rate after treatment in the present study. The irregular shape may allow clinicians to predict keloid recurrence more easily than keloid size, because the setting of the cutoff value of the size proposed varied depending on the studies.

Completely contrary to the past reports,2, 3, 4 the history of the previous surgery for the lesion was a good prognostic factor in the present study. The indication for postoperative RT was assessed for each case at our institute, and earlobe keloid tended to receive only surgical excision at the first time as written in the result section. Earlobe keloid showed a tendency for a better local control than non-earlobe keloid, although the difference was not significant. Accordingly, the involvement of selection bias was suspected to be a result of the relationship between the local control rate and the previous surgery.

Lesions site with high or low stretch tension was not correlated with local control rate in the current study, in contrast to the past reports.1,3 The result of the current study may be affected by the bias involving total radiation dose, because the lesions at the high stretch site were more likely to receive a total of 20 Gy irradiation dose than lesions at the low stretch site.

The relationship between interval time from surgery to RT and keloid local control remains controversial.1,3,4 The intervals were classified into the same day and after the next day in the present study, and this classification may be easier to use in clinical practice than classification by precise time as done in past reports, yet there was no significant difference between the interval time and local control rate in this study.

Tranilast did not show any improvement of local control rate in the study. The prescription of tranilast was at the discretion of the plastic surgeon, and tranilast may have possibly been prescribed for patients with lesions that seemed to be more likely to recur. Therefore, further investigation would be needed to reach the conclusion whether tranilast is effective or not in a combined use with postoperative RT.

This study had several limitations. The study was conducted at a single institute with a relatively small sample size. The majority of lesions were not pathologically diagnosed and were only clinically diagnosed, although this should not be a problem as keloids can usually be easily diagnosed with only a medical history and by appearance. Additionally, no differentiation was made between keloids and hypertrophic scars in the study as it is considered impossible to perfectly distinguish between them. As this was a long-term retrospective study, treatment policies including RT regimen were not unified. Furthermore, tape fixation, local injection, and ointment use after postoperative RT were not evaluated. The total number of lesions in a patient was not investigated in cases with multiple lesions due to insufficient records. Regular or irregular shapes were usually determined subjectively and not based on quantitative or detailed assessments; however, this may not be a problem since judging a lesion’s shape is relatively straightforward. The definition and the timing of recurrence included patient’s own evaluation. There were two definitions of recurrence with patient evaluation or plastic surgeon evaluation, and the two evaluations may not be consistent. Surveys on adverse events also depended on patient’s own assessment. However, allowing patient evaluations may be unproblematic since a keloid is not a malignant condition and is usually treated for patient satisfaction.

5. Conclusions

Multiple lesions and irregular shape were suggested to be the risk factors for keloid recurrence after postoperative electron beam RT. The effectiveness of tranilast in a combined treatment with electron beam RT was not demonstrated in the study. Further investigation with large population is still needed for optimal treatment of keloid.

Conflict of Interest

Sadayuki Murayama received a research grant from Canon Medical Systems outside of the submitted work. The remaining authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Financial disclosure

The authors received no specific funding for this work.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Osamu Nishizeki and Kuniko Higaonna for their helpful comments, for treating a lot of patients included in this study, and for their cooperation in data acquisition.

References

- 1.Shen J., Lian X., Sun Y. Hypofractionated electron-beam radiation therapy for keloids: retrospective study of 568 cases with 834 lesions. J Radiat Res. 2015;56(5):811–817. doi: 10.1093/jrr/rrv031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Klumpar D.I., Murray J.C., Anscher M. Keloids treated with excision followed by radiation therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31(2 Pt 1):225–231. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(94)70152-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Viani G.A., Stefano E.J., Afonso S.L. Postoperative strontium-90 brachytherapy in the prevention of keloids: results and prognostic factors. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2009;73(5):1510–1516. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2008.07.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kovalic JJ, Perez CA. Radiation therapy following keloidectomy: a 20-year experience. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1989;17(1):77–80. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(89)90373-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ogawa R., Yoshitatsu S., Yoshida K. Is radiation therapy for keloids acceptable? The risk of radiation-induced carcinogenesis. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;124(4):1196–1201. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181b5a3ae. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xu J., Yang E., Yu NZ. Radiation therapy in keloids treatment: history, strategy, effectiveness, and complication. Chin Med J (Engl) 2017;130(14):1715–1721. doi: 10.4103/0366-6999.209896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dinh Q., Veness M., Richards S. Role of adjuvant radiotherapy in recurrent earlobe keloids. Australas J Dermatol. 2004;45(3):162–166. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-0960.2004.00079.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van Leeuwen M.C., Stokmans S.C., Bulstra A.E. High-dose-rate brachytherapy for the treatment of recalcitrant keloids: a unique, effective treatment protocol. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2014;134(3):527–534. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000000415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ragoowansi R., Cornes P.G., Moss A.L. Treatment of keloids by surgical excision and immediate postoperative single-fraction radiotherapy. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003;111(6):1853–1859. doi: 10.1097/01.PRS.0000056869.31142.DE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Borok T.L., Bray M., Sinclair I. Role of ionizing irradiation for 393 keloids. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1988;15(4):865–870. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(88)90119-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kuribayashi S., Miyashita T., Ozawa Y. Post-keloidectomy irradiation using high-dose-rate superficial brachytherapy. J Radiat Res. 2011;52(3):365–368. doi: 10.1269/jrr.10159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sclafani A.P., Gordon L., Chadha M. Prevention of earlobe keloid recurrence with postoperative corticosteroid injections versus radiation therapy: a randomized, prospective study and review of the literature. Dermatol Surg. 1996;22(6):569–574. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.1996.tb00376.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ogawa R., Huang C., Akaishi S. Analysis of surgical treatments for earlobe keloids: analysis of 174 lesions in 145 patients. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2013;132(5):818e–825e. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3182a4c35e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guix B., Henríquez I., Andrés A. Treatment of keloids by high-dose-rate brachytherapy: a seven-year study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2001;50(1):167–172. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(00)01563-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mankowski P., Kanevsky J., Tomlinson J. Optimizing radiotherapy for keloids: a meta-analysis systematic review comparing recurrence rates between different radiation modalities. Ann Plast Surg. 2017;78(4):403–411. doi: 10.1097/SAP.0000000000000989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ogawa R., Miyashita T., Hyakusoku H. Postoperative radiation protocol for keloids and hypertrophic scars: statistical analysis of 370 sites followed for over 18 months. Ann Plast Surg. 2007;59(6):688–691. doi: 10.1097/SAP.0b013e3180423b32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shin J.Y., Lee J.W., Roh S.G. A comparison of the effectiveness of triamcinolone and radiation therapy for ear keloids after surgical excision: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2016;137(6):1718–1725. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000002165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kal H.B., Veen R.E., Jürgenliemk-Schulz I.M. Dose-effect relationships for recurrence of keloid and pterygium after surgery and radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2009;74(1):245–251. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2008.12.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wagner W., Alfrink M., Micke O. Results of prophylactic irradiation in patients with resected keloids: a retrospective analysis. Acta Oncol. 2000;39(2):217–220. doi: 10.1080/028418600430806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ogawa R. Keloid and hypertrophic scars are the result of chronic inflammation in the reticular dermis. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18(3) doi: 10.3390/ijms18030606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Arima J., Huang C., Rosner B. Hypertension: a systemic key to understanding local keloid severity. Wound Repair Regen. 2015;23(2):213–221. doi: 10.1111/wrr.12277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Arno A.I., Gauglitz G.G., Barret J.P. Up-to-date approach to manage keloids and hypertrophic scars: a useful guide. Burns. 2014;40(7):1255–1266. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2014.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yamada H., Tajima S., Nishikawa T. Tranilast, a selective inhibitor of collagen synthesis in human skin fibroblasts. J Biochem. 1994;116(4):892–897. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a124612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nanba Y., Oura T., Soeda S. Clinical evaluation of tranilast for keloid and hypertrophic scar: double-blind comparative study with heparinoid. Nishi-Nihon Hifuka. 1992;54:554–571. Japanese. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Japan Scar Workshop. Japan Scar Workshop Scar Scale 2011, http://www.scar-keloid.com/pdf/JSW_scar_scale_2011_EN.pdf. [Accessed February 4, 2019].

- 26.Japan Scar Workshop. Japan Scar Workshop Scar Scale 2015, http://www.scar-keloid.com/pdf/JSW_scar_scale_2015_EN.pdf. [Accessed February 4, 2019].