Abstract

Empathy, as an essential personality trait of human beings, has been studied rigorously in the field of nursing and medical sciences. Nowadays, universities are also endeavoring to develop empathy with particular courses or tailored content among the students. The English language classroom acts as a dynamic platform to impart education for empathy. Yet there is a paucity of research related to the outcomes of such initiatives. The current study revolved around an English language course that is primarily designed to improve students' proficiency in English required for them to be empowered with the compatibility of tertiary education. The secondary focus of the course concerned the cultivation of empathy that is inevitable not only for the academic journey but also for social wellbeing. The present study was designed to investigate the contents, based on theoretical grounds, of the English language classroom and to trace the outcomes of such an empathy-teaching. A phenomenological approach was adopted to conduct the study, in which document analysis and semi-structured interviews with 10 participants shaped the instrumentation of data collection. The current study adopted thematic analysis to analyze the semi-structured interview data. The findings projected that the contents harnessed to cultivate empathy corresponded to the theoretical aspects of empathy development. The semi-structured interview data was a testimony of the nature of empathy practice inculcated among undergraduate students.

Keywords: Psychology, Education, Empathy, Classroom instruction, Language classroom, University, Cultivation of empathy

Psychology; Education; Empathy; Classroom instruction; Language classroom; University; Cultivation of empathy.

1. Introduction

The essence of an individual's identity as a human being is empathy. Empathy is an indispensable human quality that shapes the interpersonal actions of human beings. Irrespective of personal, professional, communal, and social settings, the exhibition of empathy is an undeniable priority. Therefore, empathy is a compulsory human trait that occupies a significant place in the field of research. To illustrate, the past few decades have been the years of exerting eloquent focus on empathy and its practice in the spirit of diffusing the essence of empathy globally (e.g., Cruz and Patterson, 2005; Marx and Pray, 2011; Stebletsova and Torubarova, 2017; Franzese, 2016). Most of the studies explored the extent of empathy possessed by people involved in health or medical sciences. Precisely, Marx and Pray (2011) reported that empathy has been eloquently discussed in the fields including psychology, moral education, business, law, feminism, and more, “with each perspective adopting different definitions and aspects of the concept”. To put empathy into practice, researchers suggested diverse institutional inputs that induce an individual to inculcate empathy. The attempts of training or teaching empathy and the outcomes of such efforts have been documented in the relevant literature.

Since 1960', developing empathy through training has been being discussed as a crucial topic of research, and especially it has always been a matter of debate and discussion whether the skill of empathy can be learned or it is completely intrinsic in human nature (Şahin, 2012). However, several studies looked at empathy as a learnable skill and affirmed that it can be strengthened through education and practice (Ançel, 2006; Cunico et al., 2012). Furthermore, Taridağ (1992, as cited in Şahin, 2012) mentioned that although the ability of empathy cannot be taught directly, the inherent potentialities of empathy can be nurtured through training. Apart from that, regarding the development of empathy, multiple research works have also pointed out four major categories of empathy training thus empathy development i.e. (1) modeling, (2) didactic, (3) role-playing and (4) experiential (Dalton et al., 1973; Fine and Therrien, 1977; Gladstein and Feldstein, 1983; Greenberg and Goldman, 1988). To illustrate, Dalton et al. (1973) have clarified in their research that one of the categories named modeling had left a crucial impact upon the training of empathy and counseling behavior through its behavior modification and modeled learning experience. Moreover, referring to Eisenberg and Delaney (1970) they had strengthened their point of supporting the practicality of modeled-learning in behavior modification. Afterward, Fine and Therrien (1977) had also conducted a study on the effects of a systematically designed training program on empathy building. The result of the study indicated that this didactic training of empathy successfully and significantly increased the empathic judgment among the trainees.

Furthermore, focusing on the Asian socio-cultural background, improving the ability to nurture empathy has a large significance regarding the contribution to the establishment of an effective intercultural communication because one of the major characteristics of empathy is to develop the perspective of another human being, regardless of having diverse socio-cultural differences (See Chen et al., 2007 for detail). A subsequent study showed that educating the students about cultural empathy had resulted in decreasing the cultural stereotypes during an international Chinese Language program since cultural stereotypes can function as an impediment to language learning by creating refusal and inclination against the culture of the target language (He, 2017). Furthermore, another succeeding research, conducted on 60 Chinese undergraduate students of Zhejiang Ocean University, has found out that the ability of cultural empathy is positively correlated with the ability of cross-cultural communication to enhance the quality of language learning (Jiang and Wang, 2018).

Apart from these, different studies have been conducted globally to evaluate the incorporation and functionality of empathy in tertiary education (e.g. Marx and Pray, 2011; Zembylas, 2012; Chen et al., 2007; Jiang and Wang, 2018). For example, the qualitative research on the abroad-studying English language learners, conducted in Cuernavaca, Mexico suggested that empathetic understanding had helped the students to channel their frustrations regarding differences of culture, language, and race (Marx and Pray, 2011). It was predicted that empathy is going to be one of the key factors in the increased percentage of English Language Learners (ELL) in the US and the concept of empathy will have a firm contribution to the development of the upcoming teaching strategies (Washburn, 2008) since the prediction made by the US Census Bureau suggests that the number of students learning the English language is going to rise to 40% of the entire student population of the US by 2030 (Herrera and Murry, 2005). However, not only in language learning but the concept of empathy has also been researched globally in medical studies (e.g. Spencer, 2004; Pedersen, 2010; Sulzer et al., 2016; Yuen et al., 2019).

Seemingly evident is it that the culture of teaching empathy in the language classroom is not a new phenomenon. The past few decades have been the years of exerting subtle attention to the studies concerning the cultivation of empathy among students through teaching and training. Empathy is one of the personality traits that is much needed in the era of science and technology. On a pragmatic level, with the widespread growth of modern technology and the multifaceted exposure of artificial intelligence, although the doctors, nurses, and educators enjoy tremendous support, artificial intelligence or even the most recently developed robots lack the presence of empathy thus cannot yet replace a properly trained professional (Inkster et al., 2018). Therefore, the intensity of empathy becomes an undeniable priority. Taking such reality into account, universities have designed courses to enable students to learn and practice empathy. Of particular medium to impart empathy is the English language course, as aforesaid, that harnesses materials essential to teach empathy. Building on such an English language course at the focal university, the current study attempted to shed light on the classroom inputs to teach empathy, the way of incorporating these to the classroom, and the outcomes of such initiative. In the following sections, we highlighted the concepts associated with empathy and its development. After that, we designed the method of the study in which we defined the context and rationale of the study. Next, we presented our findings. Finally, we drew the conclusion followed by the discussion part.

1.1. The concept of empathy

The discussion of empathy came into prominence in the English language when British Psychologist Edward Ttichener used it for the first time in 1909 as a translation of German term Einfuhlung which means ‘feeling into’ or ‘in feeling’. Due to the passage of time, empathy is an inevitable part of human life. Initially, empathy is identified as a complicated concept. Bell (2018) acknowledged it by stating that the concept of empathy continues to be fine-tuned as new sections of ideas emerge, with the increase of studies that advance the definitions, understanding, and subtypes of empathy. For instance, Barrett-Lennard (1962) conceptualized empathy as an active process that grows the instinct in human beings to see, feel, or internalize another's perspective of the world. Rogers, building on the professional ground, defined empathy as “to sense the client's anger, fear, or confusion as if it were your own, yet without your anger, fear, or confusion getting bound up in it” (1957, p.99). This is particularly for the counselors, who need to understand the clients' experiences of suffering. Later on, it was summarized as “empathy truly appears to be a mutual process of shared communicative attunement” (Elliott et al., 2011, p.47). On this ground, empathy acts as a bridge to connect counselors and clients to feel safe and understood. Meshcheryakov and Zinchenko (2004) in their dictionary on psychology defined empathy as an instrument that generates one's attention towards other people. Stebletsova and Torubarova (2017) associated empathy with emotional generosity, sensitivity, and attention towards other people to address their problems, troubles, and joys. According to them, empathy enables them to perceive other people's feelings in an emotional ground. Empathy has been shaped in fundamental literature on second language learning and teaching as “putting yourself into someone else's shoes” (Brown, 2000, p.153).

Considering mental health, practitioners shed light on two aspects of empathy: affective empathy and cognitive empathy (Bodenhorn and Starkey, 2005). Cognitive empathy is attained by logically embracing another's situation. Precisely, cognitive empathy skills can be learned through reasoning and connecting with others through thoughtful reflection. Affective empathy, on the other hand, is embedded in the emotional response to another person's feelings or predicaments. It is inherent, which allows a person to experience another's emotions. Batson (2009) conceptualized more than eight conditions or experiences where the term empathy can be functional. These three conditions entail knowing other's internal state, including thoughts and feelings, adopting the posture or matching the neural responses of an observed other, attempting to embrace how one would think and feel in the other's place, and internalizing the distress another person is undergoing. Furthermore, Goleman (2006) shed light on three types of empathy, which are cognitive, emotional, and compassionate. For a start, cognitive empathy is attached to knowing what others feel, and what they might be thinking, which is similar to Batson's (2009) illustration. Laird (2015) referred it to perspectivation. Next, emotional empathy is enacted to feel something along with others in a way that appears as something contagious. The third type, compassionate empathy, is more operational in the sense that it leads a person to understand others' feel with them and offer help if it is necessitated.

Factors influencing empathy include perceived similarity to other people, nurturance, culture, and neurological functions (Laird, 2015). The perceived similarity is set with the idea that people feel a person's situations to the extent that they perceive these to be similar to themselves. Next, nurturance is seen as a human instinct that drives people to practice empathy through caring and protecting one's young. Finally, cultural differences have been identified as a driving force that yields a varying degree of empathy. Empathy, a mechanism that drives people to step out of the selfhood (De Vignemont and Singer, 2006), functions with the assistance of mirror neurons that is situated in the premotor cortex of the brain (Gallese et al., 2007) and creates an instinct that influences human beings to feel the actions of other people in a given situation as the same as they would react in a similar situation (Bell, 2018). Alford (2016) furthered it by stating, “mirror neurons work by assuming that you intend what I would intend in a similar situation” (p. 8). Another school of thought suggested that empathy is the result of “an emotion-regulation process used to soothe personal distress at the other's pain or discomfort, making it possible to mobilize compassion and helping behavior for the other Decety and Lamm (2006, as cited in Bell, 2018, p. 109).

1.2. Development of empathy

Bell (2018) conceptualized the employment of creative activities that encompass both cognitive and affective empathy. Although the activities purportedly increase overall empathy, they are selected for the individual categories based on the ability of the activity to stimulate learning that tailors the development of the particular type of empathy. For instance, Bell (2018) propounded that activities for increasing the extent of cognitive empathy results in thoughtful reflection, cognitive perspective-taking, and challenging one's perspective and beliefs through a greater understanding of another's experience. On the other hand, affective empathy activities are distinct. Generally, these are specific to creative approaches that bypass cognition and speak directly to the development of felt reactions to other situations.

Furthermore, Gladstein and Feldstein (1983) believe that role-taking can be another effective way of building empathy and they also came up with a detailed analysis of the development of empathy that objectifies the idea of the three stages of empathy-building i.e. (1) emotional reaction, (2) role-taking (3) cognitive suspension. With a particular focus they mentioned here that emotional reaction is an ‘unobservable state’ thus also immeasurable; role-taking, however, involves the understanding of others' perception of the world through situational imagination; finally, cognitive suspension refers to the process of getting rid of different socio-cultural beliefs so that people can nurture empathy non-judgmentally.

Moreover, as a tool for empathy-building, experiential therapy emerged in the ‘40s and ‘50s and it refers to therapies based on a humanistic and phenomenological approach, however, by the ‘60s several research works had started to be conducted specifically on the instructive training programs on the experiential theory and those research works contributed vastly in the development of empathy through multifaceted experiential therapy (Greenberg and Goldman, 1988).

Finally, different social promotions and positive initiations, increased support from the socio-cultural environment, developing various ethical perceptions, etc. can be expected to have a significant positive outcome in building empathy among university students since these social reinforcements have notable contributions in developing the sense of empathy among children (Eisenberg & Strayer, 1990). Another method of developing empathy can be the contextual simulation through role-playing activities (Brunero et al., 2010; Bosse et al., 2012). Some researchers have also evaluated the effectiveness of reflective writing as a training tool for building empathy and have found out that reflective writing is capable of enriching the quality of empathetic judgment among the trainees (Shapiro et al., 2004; Ozcan et al., 2011). In a nutshell, it is possible to come to this resolution that various researchers have shown this very explicitly that empathy training is significantly effective for the improvement of the sense of empathy among the students regardless of having the difference in levels and ages (Şahin, 2012; Bas-Sarmiento et al., 2017).

1.3. The study

The current study was based on the English language course that is usually offered to the first-year undergraduates from all disciplines at the focal university in Bangladesh. This fundamental English course was devised to enrich their compatibility in terms of the English language, which was necessitated to continue their university education for the next four years. At the same time, considering the social reality and the nationwide violence, university authority felt the need to cultivate empathy among students with the hope of eradicating the crisis. With such aim and objectives ahead, we incorporated empathy as content for the English language classroom. Stebletsova and Torubarova (2017) postulated that a foreign language (FL) can shuttle and develop empathy among students. Therefore, as they put forward, the FL classroom acts as an effective setting to develop empathy. Most relevantly, educational inputs are useful in maintaining and developing empathy in undergraduate students (Batt-Rawden et al., 2013). Now the pressing question is, to what extent our content for building empathy in the language classroom is in line with the theoretical ground on building empathy and what is the outcome of such empathy-training imparted in the language classroom. Pertinently, the current study was guided by the following research questions:

-

1.

How were the contents used for developing empathy in the English classroom in line with the theoretical ground?

-

2.

How was the perception of the undergraduate students regarding the nature of the practice of empathy developed by the integration of empathy-training in an English language course?

Although in Bangladesh, the study related to empathy-teaching and - development, and its outcomes, in primary, secondary and tertiary education, has not been directly institutionalized so far, the significance of the studies on training and outcome related to empathy cannot be overlooked considering the nationwide degradation of moral values and the increasing rate of hatred-crimes.

2. Method of the study

In this section, we shed light on the context, setting, and design of the study.

2.1. Context of the study

According to one crime-statistics provided by Bangladesh Police, 351 cases of murders, 1139 cases of woman and child repression, and 46 cases of kidnapping have been filed in 2019 (see https://www.police.gov.bd/en/crime_statistic/year/2019). Furthermore, another national newspaper named New Age reported a more recent statistic which estimated that in 2019, 1538 rape cases have been filed within the first four months alone which also indicates that almost 13 (12.81 more precisely) incidents of rape have occurred every day within these four months (seehttp://www.newagebd.net/article/72764/bangladesh-sees-nearly-13-rapes-every-day). Several incidents of extreme hatred-crimes occurred in 2019; one of the recent incidents is when a 40-year-old woman named Taslima Begum Renu was beaten to death by a mob based on a mere suspicion from rumors (see https://www.thedailystar.net/city/news/beating-woman-dead-badda-prime-accused-arrested-1776199). Another incident that had shaken the entire nation when a girl of 19 named Nusrat Jahan Rafi was burned to death because of filing a complaint against her school headmaster for sexual harassment (see https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-47947117). In late June 2019, a video went viral on social media when a man, aged 25, was publicly murdered by two men with sharp machetes and this sort of a hatred-crime was a nationwide shock for the country (see https://www.thedailystar.net/frontpage/news/man-killed-front-wife-1763131). Of particular pathetic news is that the criminal activities or violations are also being observed in the reputed higher education institutes of the country. For instance, the last incident that shocked the entire nation was the killing of an undergraduate student, who was brutally beaten to death by fellow students after criticizing the government online (see https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-49986893). As regards the academic setting, Ferdous and Karim (2019) reported on the classroom scenario that delineated that personalities and attitudes of the students often lower the productivity of pair and group works. For this to happen, the little acceleration of empathy can be held responsible that results in limited coordination among students.

If we look at the major research works on the correspondence between low-empathy and criminal behavior, it becomes evidential that the amount of empathy in criminals was significantly lesser than the amount of empathy in noncriminals (e.g., Burke, 2001; Bush et al., 2000; Marcus and Gray, 1998; Hogan, 1969). In line with such a claim, we can place an illustration that low-empathy leads our countrymen to commit heinous acts, which can be uprooted only through the cultivation and practice of empathy. Therefore, we can hold a strong consideration that empathy can function as a ‘protective factor’ that can play a very crucial role in suppressing certain sets of offensive behaviors (Jolliffe and Farrington, 2004).

2.2. Design of the study

Generally, the research question acts as a decisive factor in selecting the research design (Nunan, 1992). The nature of the research question is exploratory, interpretative, and phenomenological; hence, we approached them qualitatively. Gay et al. (2011) suggested that the qualitative research method is suitable for the study that is aiming at understanding the participants' opinions. Our study intended to understand the perception of the undergraduate students regarding the nature of the practice of empathy developed through an empathy-training in an English language course. The interview questions designed in this study were considered as effective for understanding the perception of undergraduates regarding the nature of the practice of empathy. Their responses defined their perceptions about how empathy can be put into practice in different situations emerged in our daily lives. The current study undertook a phenomenological approach by building on Gay et al.’s (2011) view that suggested that this approach has been effective for exploring the experience, outcome, or learning of activity from the participants' perspectives. Besides, a phenomenological study was adopted, since it guided the researchers to explore how the students perceived the phenomenon (e.g., the perception developed through empathy-training regarding the real-life practice of empathy) in their life (Creswell and Poth, 2017). The fundamental concern of the second research question was to understand the perception of the undergraduates, immersed in the English language course, regarding the nature of the practice of empathy. Eventually, the current study was an attempt to document the individual account that notified the impact of empathy-training from the perspective of the enrollees. In the current study, the population was undergraduates who enrolled in an English language course in the first semester of the ‘X’ university (Pseudonym). Numbering around 1000, students immerse in this English language course every semester at the focal university. We selected the participants based on purposiveness. Cohen et al. (2013) defined that the deliberate intervention in the sampling process is known as “purposive sampling” (p. 115). The selection of the samples for the study was accomplished based on what Creswell and Poth (2017) called accessibility and purposiveness. We chose the participants who were in the second year of the undergraduate programs. We selected them because they had completed two more semesters after the completion of that particular English language course since this course is usually offered in the first semester. As such, they had the opportunity to face different academic and social sites, which might require the implications of empathy. Based on these purposes, we selected ten subjects depending on Creswell (2013) that recommended phenomenology with three to ten cases and Van Manen (2002) that estimated the sample size with the range of six to twelve, with the belief that such sample size is adequate to explain the phenomenon under study. Our participants belonged to diverse disciplines like the Department of Computer Science and Engineering (2), Department of Mathematics and Natural sciences (2), Department of Pharmacy (2), Business School (2), and School of Law (2). Subject to the ethical considerations, the current study espoused the amendments indicated by Creswell and Poth (2017). Eventually, we clearly articulated the purpose of the study in front of the participants. Additionally, they were informed about how the findings of the study will be disseminated, what their rights were, their scope to withdraw from the study, how the study will benefit themselves along with other university students and the society, the guarantee of maintaining anonymity and the confidentiality of the study. With all these being shared and understood, our participants expressed their consent to take part in the study. Furthermore, we obtained verbal consent the senior director of the institute at the focal university. Typically, this is the process practiced in Bangladesh for Social science research.

To answer our first research question, we carried out a document review. Punch (2005) advocated the use of documentary data in addition to other forms of data collection tools like an interview. According to Bryman (2012), some of the documents of the organizations remain stored in the public domain especially on the World Wide Web. However, the documents reviewed for the current study were unavailable in such public domains, as these were authentic materials prepared by English language teachers of the focal university to harness in the English language course. We reviewed the materials and only presented the key parts in our ‘finding of the study’ section. Furthermore, to answer our second research question, we undertook a semi-structured interview with the participants. We designed semi-structured interview questions by conceptualizing the ‘empathy quotient’ incorporated in Baron-Cohen and Wheelwright's (2004) study. We developed questions that enabled us to understand the perception of the university undergraduates regarding the nature of the practice of empathy. Given below are the research matrix that contained semi-structured interview questions of the current study and the themes and codes that shaped the findings of the study (see Tables 1 and 2):

Table 1.

Research matrix.

| Aim | Interview Questions | Source of Data | The technique of Data collection | The technique of Data Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Understanding the impact of empathy-training on university undergraduates undergone this English language course |

|

Students | Semi-structured interview | Thematic Analysis |

| ||||

| ||||

| ||||

| ||||

| ||||

|

Table 2.

Themes and codes of the data analysis.

| Research Question | Themes | Codes |

|---|---|---|

| How was the perception of the undergraduate students regarding the nature of the practice of empathy developed by the integration of empathy-training in an English language course? | Understanding the importance of emotional attachment to a friend's problem | Using logic; maintaining emotional connectivity; embracing others' perception |

| Feeling the necessity of valuing others' time as an act of empathy | Maintaining a social balance; development of interpersonal communication skills; development of time management skills | |

| Realizing the importance of listening to others | Building teamwork skills; securing effective communication | |

| Perceiving lying as an act of empathy | Maintaining interpersonal relationship; delivering motivation | |

| Understanding the importance of empathetic manners | Spreading harmony in the society; projecting a positive self-image | |

| The intensity of emotion | Fluctuations of emotion based on gender; controlling emotion because of the social reality and self-security | |

| Dexterity in dealing with social issues | Exposure to diverse communities; non-judgmental perception |

The collection and analysis of data were driven by the research question. Initially, the data collected through the semi-structured interview was transcribed. After that, the transcriptions were coded to create themes. Eventually, the transcripts were scanned repeatedly for recurring themes (Creswell and Poth, 2017). The table given below contains detailed information on the codes and themes of the study, in relation to the research question.

2.3. Findings of the study

Two types of data formulated the findings of the current study. One type of data contained the information extracted by conducting a document analysis. The semi-structured interview shaped another form of data for the current study. Firstly, we presented the data gathered from the document analysis. Followed by this, we presented the data comprised of the responses of the semi-structured interview.

2.4. Findings of the document analysis

We reviewed the lesson plans and materials used in the English language course to empower students in an empathetic manner. In the following section, we highlighted the information extracted from the document analysis.

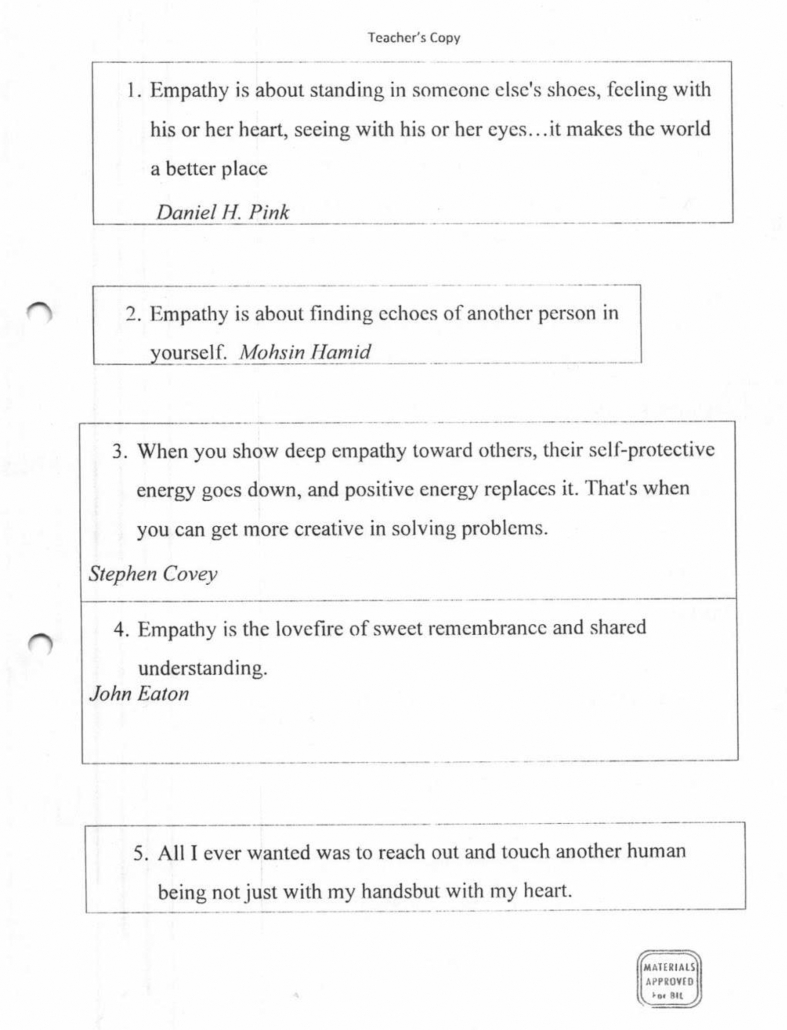

2.4.1. Data yielded from class 1

In the classroom, we attempted to teach empathy, as part of the language-teaching contents, so that students can learn to be tolerant, patient, and compassionate in both their academic and social life. Accordingly, we distributed chits that contained quotes (for example, Figure 1), which were highly related to the paradigm of empathy. To illustrate, the first class of empathy included different proverbs that cultivated the notion of empathy in students' minds. Such as, ‘I believe empathy is the most essential quality of civilization - Roger Ebert’, created an initial impression in students' minds about the impact of empathy in human life. That is how the first class on empathy shaped the ‘figure of empathy’ in students' minds. Concerning the classroom activity, we asked students to read the quotes in pairs and discuss what was their understanding of empathy. After that, we called some pairs in front of the class to share understanding with their peers. They read the assigned quotes first and then explained their understanding by yielding more focus on the implications of the quotes in both academic and social life.

Figure 1.

Chits containing quotes.

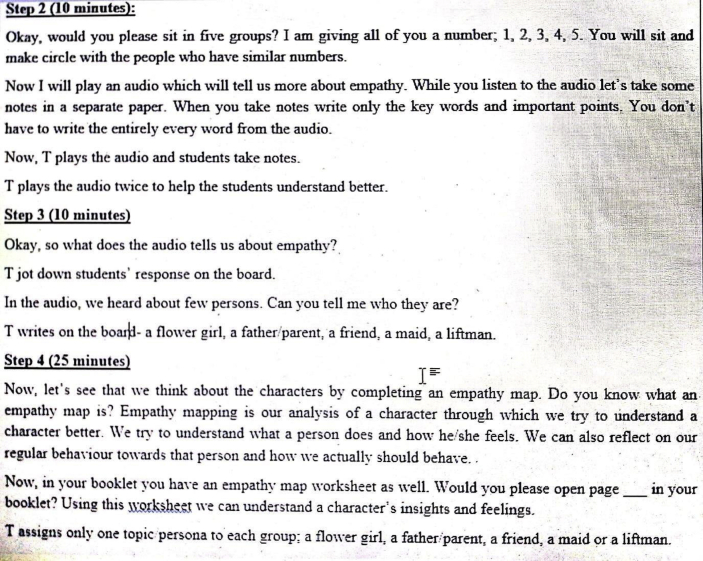

2.4.2. Data yielded from class 2

We also carried out a follow-up class named as ‘Nurturing Empathy’. In this class, we exerted a subtle focus on five cases that potentially delved into the empathetic stance of our students. As part of the activities, students listen to the ‘audio clip’ on the empathy subject to the lifestyles of a flower girl, a father/parent, a friend, a maid, and a liftman (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Lesson plan for nurturing empathy.

Source: Authors

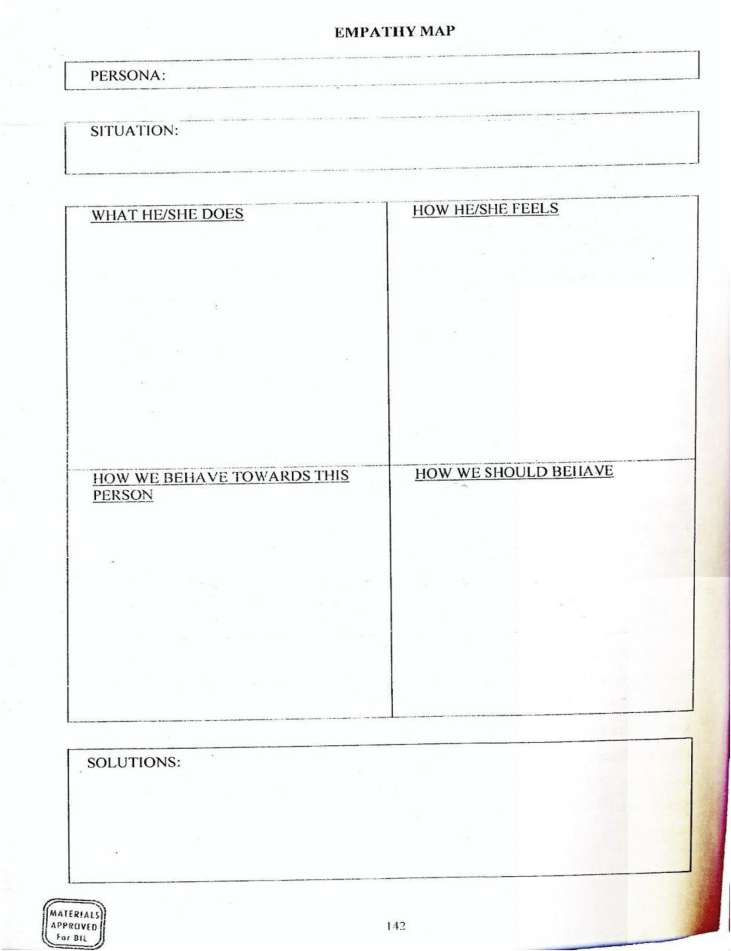

After the students finished listening to the audio clip, we entrusted them with the task that required students to complete an empathy map (see Figure 3). The following activity concerned presenting the empathy maps standing in front of the class.

Figure 3.

Empathy map worksheet.

2.4.3. Data yielded from class 3

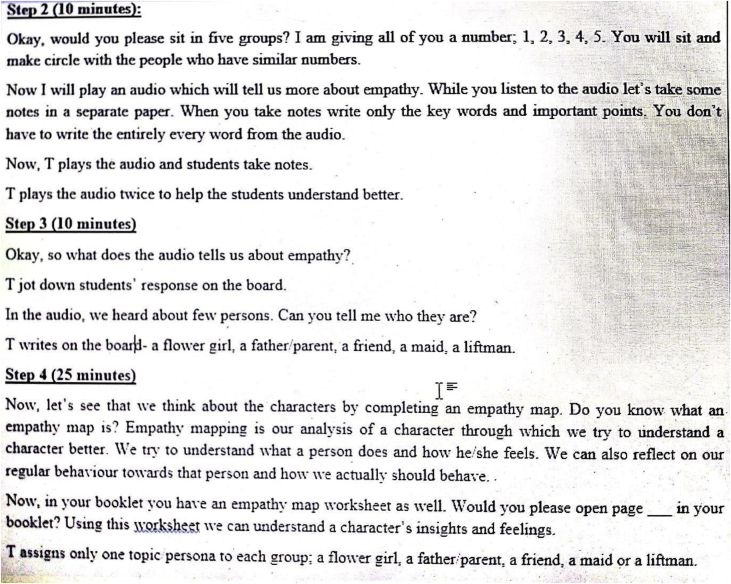

The next class has been named as ‘Eulogy’ and designed as the reminiscent of the three individuals who left the signature of their empathy by sacrificing their lives to glorify friendship at the event of a heinous terrorist attack on ‘Holey Artisan Restaurant, Dhaka’ (seehttps://www.thedailystar.net/frontpage/dhaka-attack/blood-shock-horror-1249471). We shed light on their stories of sacrificing lives to portray the extent of empathy that they contained to upheaval friendship. We expected to broaden the affective empathy of our students through the retrospection of the night that was characterized by blood, shock, and horror. Being in the groups, students reflected on the reading articles that subsumed the stories of the three individuals who sacrificed their lives that night. After that, students shared their understanding, words of empathy exhibited by the deceased souls, and their learning out of this event. The following activity (see Figure 4) concerned writing a eulogy on Abinta Kabir, Tarashi, and Faraz Hossain who were just killed because they did not fly away by making their foreign friends endangered.

Figure 4.

Lesson plan for Eulogy classroom.

2.5. Interview data

The findings of the semi-structured interviews were presented under the themes generated by the interview questions. Besides, we also created sub-themes to present our data with more specifications and clarity.

Understanding the Importance of Emotional Attachment to a Friend's Problem: In response to our first question, the participants admitted the importance of emotional attachment to a friend's problem, with different aspects being considered. Through their verbatim, these following sub-themes had been derived.

Logic as a Determiner: With emphasis, the participants focused on the logical analysis of any situation or problem instead of handling them based on mere emotional judgment. As P1 articulated,

To comprehend any sort of issues or problems faced by a friend, being too emotional can be considered as a drawback. If I truly want to help someone I must look at the situation with a more logical approach.

Some of the participants were of a similar view. For instance, P3 maintained,

…it is logical to apprehend a problem by being emotionally stable and patient.

From the aforesaid verbatim, it became obvious that the participants of the study preferred to behave with proper resonance. They have been logical when dealing with problems faced by their peers and friends.

Importance of Emotional Connection: However, the respondents also focused on the importance of a certain level of emotional attachment with friends to help them effectively and efficiently. For example, P2 added,

… being emotionally connected with a friend's problem is equally important as being logical to understand their problem.

Another participant P4 also made a corresponding statement,

… stronger emotional connection will eventually result in a higher effort to help.

The above-mentioned statements of the participants suggested that they strongly acknowledge the importance of the establishment of an emotional connection to respond to the problems of their friends. In other words, higher emotional connection results in a higher amount of effort to struggle against a certain problem.

Understanding Others' Perception: The participants also emphasized the importance of emotional attachment as a tool for developing the quality of understanding the perception of others non-judgmentally. P6 on this ground stated,

… emotional attachment is important to understand the person in suffering, from his or her perspective … In short, this is like putting myself at his or her place as precisely as possible.

The foregoing statement of the participants made it transparent that they emphasized the skill of understanding others' perceptions through an emotional connection. To conclude, we observed the mixed responses from the participants subject to the importance of emotional attachment. Therefore, we can finalize that although they initially focused on the logical approach of addressing a friend's problem, they did not deny the existence of the emotional attachment.

Feeling the necessity of Valuing Others' Time as an Act of Empathy: The second question was about why it is necessary to reach somewhere on time and to value the time of others as an act of empathy. The collective responses of the participants notified their attention to value others' time. They highlighted a few aspects that necessitated the importance of valuing others' time by being presented somewhere on time.

Sustaining Social Balance: According to the responders, not only as an act of empathy, rather sustain the social balance, reaching at social gatherings on time is very important. P7 articulated,

… if we fail to reach on time, it not only shows disrespect towards others but also disrupts any social event.

Development of Social Communication: Responders also thought that valuing others' time can also result in the development of certain interpersonal communication skills. As P5 responded,

… timing should be fixed among friends from the very beginning… If I have any problems, I must let my friend know beforehand that I'll be late or I can't come…

Development of Time Management Skills: As a result of valuing others' time, significant examples of time management skills were also found from the responses of the participants. For example, participant P8 responded,

… even in a jam-packed city like Dhaka, we must keep some extra time to reach a place on time.

If we shed some light on the above-exemplified statements of the participants it becomes comprehensive that the participants need to maintain the social balance and social communication through effective time management and by reaching social events on time.

Realizing the Importance of Listening to Others: The participants, in response to the question regarding why it is important to listen to others as an act of empathy, yielded diverse premises that suggested their eloquent admission to the fact.

Teamwork Skills: Along with the empathic value of listening to others, the respondents have also focused on the importance of listening to others as a tool for building teamwork skills. To exemplify, participant P6 responded,

Undoubtedly it is important not just as an act of empathy but to understand the true perspective of that person as well… For example, we must also keep in mind that particularly in a team if one member keeps talking without listening to others, it will be extremely unfair to the other team members.

From the aforementioned statement of the participant, it became quite suggestive that the participants not only consider the act of listening to others as an act of empathy but they also consider this sub-skill of communication as a tool for achieving advanced team-work skills.

Effectiveness of Communication: The participants also pointed out the increased-effectiveness of communication as a result of listening to others. For example, P8 articulated,

… also if I don't listen to a person during a conversation properly, it will result in ineffective communication because responding without listening would be completely meaningless.

From the statement presented above, another point has become quite transparent that this listening to others as an act of empathy leaves an important contribution to effective communication. During the activities of an empathy class, the participants were specially instructed to come up with the possible negative outcomes of not listening to each other properly. Therefore, listening to others with proper attention as an act of empathy with its by-product of enhanced communication projects strong guidance of the classroom activity.

Perceiving Lying as an act of Empathy: The participants accorded the fact that one can be inclined to telling a lie as an act of empathy. Highlighting the maintenance of interpersonal communication and some other factors, they expressed their stance in favor of telling lies to maintain social harmony.

Maintaining Interpersonal Relationship: For the participants, maintaining the balance of relationships with friends and family, which is also a key component of social balance, is the strongest driving force for telling lies. P10 elaborated,

… sometimes it is okay to tell lies for the sake of my loved ones because they are irreplaceable… Sometimes we have some small problems among family members that can grow bigger and bigger if we let it… so in situations like those, to stop any smaller, changing the truth slightly should not only be permitted but should also be praised.

The statement suggested that the participants wholeheartedly value their family relationships and friendships. To sustain the present and future wellbeing of these ‘irreplaceable’ relationships, they even consider the act of telling lies as a permissible one.

Motivation through Harmless Lying: The respondents considered the act of telling harmless lies as a tool for motivating a depressed friend. P9 explicated,

If a friend of mine is depressed and a lie as hope or as inspiration can make him or her feel better than it is harmless …

Here, the participants affirmed that they would consider sacrificing their morality of truthfulness for the sake of sustaining the balance of social relationships and motivating a depressed friend. A closer look furthered the idea that when the participants tried to justify the permissibility of telling lies, they only focused on the fact of emotional attachment with their friends and family members.

Understanding the Importance of Empathetic Manners: We administered the next question about the importance of empathetic manners for the growth of a better personality. As a practice of maintaining social affinity and a way of representing a positive self-image in front of society, the participants affirmed the importance of empathetic manners.

Maintaining Social Affinity: The participants expressed their consideration of empathetic manners as a mode of maintaining social affinity and enhancing social bonding. For example, P8 articulated,

… empathetic manner means making others feel good through your behavior and attaining a certain level of self-satisfaction … if a friend of mine fails in the final exam, I cannot instantly do anything to change the situation, but I can talk to him and console him. For me, this empathetic consolation enhances social bonding.

We can see that the participant strongly believes that empathetic manners and behaviors can also be considered as a tool for maintaining social affinity.

Positive Self-image: Having an empathetic manner of behavior projects a person more positively and beautifully in front of society. A person with noticeable empathetic manners is usually considered as a better human being thus respected by all. P4 illustrated,

… empathetic behaviors not only build a great character but also transform our image positively in front of society.

The participants strongly believed that empathetic manners play a strong role to develop a person's character and make a person appear more positively in front of society.

The intensity of Emotion: Our participants pointed out different catalysts become dominant when they see someone crying. They spontaneously become a part of that situation, with the intensity of emotion.

Influence of Gender: Based on gender, they experience different emotional fluctuations. Most of them affirmed that they experience a higher level of emotional influence on women. P7 expounded,

I feel very sad when I see a girl crying because women are more vulnerable to different forms of harassment in our society.

In the same token, P5 articulated.

I feel more concerned for a woman than a man, who is crying because the increasing violence against women affects me more intensely.

The responses delved that a crying woman or a woman in suffering mounts drastic pressure on them. These two respondents were males. Regardless of the difference in gender, they admitted the existence of a social violation that jeopardizes women. Being in line with their statements, other participants also voiced the suffering of the women in our society, which creates tensions for them. As such, it was evident that females accounted for the largest part of the emotional concern of our respondents.

Social Insecurity and Emotional Exposure: The participants have also raised the issue that in the current socio-political situation of Bangladesh, actions influenced by emotional intensity can lead to different risks of self-security and safety. For example, P4 articulated,

If I see somebody (unknown) crying I shall feel bad and I want to help but if I get myself or my family into trouble because of that then I can't do it … the person may have political rivals or criminal involvement.

It becomes very transparent that the participants were willing to help a person in distress, however, they also would calculate the risk of their intended action. To evaluate the approach of the participants logically, we can say that due to the compromised social security of Bangladesh and the increasing rate of crime, the participants expressed their clear disinterest regarding helping an unknown person out of emotion because they do not want to involve with any complex situation that may grow beyond their control eventually.

Building Dexterity in Dealing with Social Issues: The next question was intended to apprehend the participants' skills to handle any situations emerged in our daily worldly affairs. It was noted by the respondents that due to the exposure to diverse communities through traveling and living in different parts of the country, they have developed a non-judgmental perception which increased their level of understanding and handling different social situations with increased dexterity. As P1 expounded,

… because of my father's job I had a chance to live in different places in Bangladesh. I also experienced different types of social situations… If you mix with different types of people, you will become less judgmental and more skilled at handling several social situations.

The respondent considers having exposure to different cultures and people as a major tool for developing social skills. Moreover, the participant thinks that it also develops a non-judgmental perception among people.

The study was an attempt to explore the perception of the undergraduate students regarding the practice of empathy developed by the integration of empathy-training in an English language course. Through the interview data, it was manifestly realized that the practice of empathy had been inculcated in undergraduates' minds concerning the understanding of the importance of emotional attachment to a friend's problem and the importance of empathetic manners. Additionally, they concurred that feeling the necessity of valuing others' time, realizing the importance of listening to others, and lying to empathize are essential in daily affairs to show empathy in social sites. They also claimed their expertise, being developed through empathy training, in dealing with social issues. As such, it can be blatantly realized that this empathy-training training created a positive perceptibility among the undergraduates regarding the practice of empathy through various acts.

3. Discussion

The current study yielded data from document analysis and semi-structured interviews. Firstly, the discussion was accomplished based on the document analysis, concerning the theoretical perspectives. After that, the semi-structured interview data was discussed against the theoretical grounds and contextual reality.

3.1. Discussion on the document analysis

We intended to engage students in the discussion on empathy by using different proverbs (Figure 1) that were believed to cultivate the notion of empathy in students' minds. This is the creative activity that we incorporated in the spirit of growing cognitive empathy among students. Bell (2018) talked about ‘logically embracing others’ situations, which is acclaimed as the significant feature of an empathetic person. We put this activity into practice in the spirit of enhancing the students' ability to understand others' situations. Cognitive empathy can be learned through reasoning and connecting with others through thoughtful reflections. Through such classroom exercise, we enabled our students to reflect on the quotes through reasoning and connecting, leading them to imbibe this empathy in mind. Jolliffe and Farrington (2004) claimed a correlation between low cognitive-empathy and offending behavior. We included classroom activity (Figure 1) to assure the cultivation of effective empathetic-behavior in mind. In conjunction with this activity, we called students in front of the class in pairs and asked them to share experiences where they either received or exhibited empathy in different situations. Batson (2009) shed light on internalizing other's internal state - attempting to understand how one would think and feel in the other's place - when he conceptualized eight conditions in which empathy remains in operation. Bell (2018) claimed that the construction of affective empathy is accomplished by attuning to the felt sense that is experienced by others. Our students share their experience of receiving or sharing empathy, which notified their ability to internalize others' thoughts and feelings (internal state). This also indicated the extent to which students attempted to understand how one would think. They shared different experiences of exhibiting empathy, which we call affective empathy since it is inherent and it grows through the emotional responses that one feels. Having someone in suffering, they extended their support by any means, which is the result of the affective empathy they have had inside themselves.

Furthermore, we designed another class on ‘nurturing empathy’, which involves the lifestyles – in the form of an audio clip - of five professionals, and after listening to the audio clips students were asked to complete an ‘empathy map’ and present it in front of the class (see Figure 2 and Figure 3). We intended to nurture affective empathy by deploying these tasks along with engaging the students in English listening and speaking practices. Moreover, we selected this activity since theoretical underpinning suggested that an individual can thrive with affective empathy through an emotional response that is produced by feeling someone in struggle or suffering. To illustrate, Gladstein and Feldstein (1983) suggested that role-taking can be an effective way of emotional empathy development. They have also emphasized the three levels of empathy development i.e. (1) emotional reaction (2) role-taking and (3) cognitive suspension. Therefore, in this particular empathy class, the students had exposure to the situations through the audio clips where they can demonstrate the emotional reaction. Afterward, they were guided to express their emotional reactions towards the assigned characters through the empathy map. At the second level of role-taking, the students came in front of the class and presented the characters both by explaining their empathy maps and portraying those characters through role-playing activities through a brief presentation of an act. Finally, at the end of the class, a debrief session takes place when the students go through a process of “cognitive suspension” through self-reflection. To illustrate, cognitive suspension refers to the suspension of the stereotypical beliefs and judgmental perceptions that create an impediment to practicing empathy for an individual. As such, it can be realized that how we incorporated listening and speaking activities in the language classroom where the objectives were practicing oral and aural versions of the language, and develop a strong ground on empathy.

Subject to the ‘Eulogy’ class (Figure 4), our purpose was to excel students' affective empathy through the stories in conjunction with their speaking- and reading skills development. That is how we collectively brought cognitive and affective empathy into prominence in the language classroom. To explain, Greenberg and Goldman (1988) have presented the experiential theory of empathy development which refers to the process of integrating the experience and expression of empathy. Moreover, referring to Elliott et al. (2004), Vanaerschot (2007) illustrated that the experiential therapy of empathy development is a “process-directive” approach and it develops empathy through an exploration of the experiences. Now, in the ‘Eulogy’ class of empathy, we practiced a similar method of experiential therapy. First of all, the students go through certain articles which are contextually sensitive. Afterward, through the written form of eulogy, the students experience a primary expression of empathy through writing. We achieved two things from this class. Firstly, we circulated an orientation and practice of empathy among students, which is the fundamental concern of this class. Secondly, we involved our students in eloquently practicing the language in the classroom.

The aforementioned discussion suggested that the materials harnessed in the language classroom to continue empathy-training have been in line with the theoretical perspectives of empathy-development.

3.2. Discussion on the interview data

As regards the interview data, the importance of emotional attachment to a friend's problem has been voiced through participants' elicitations. They have admitted this importance based on three grounds namely logic, emotion, and understanding. Stebletsova and Torubarova (2017) claimed that empathy is embedded in emotional generosity, sensitivity, and attention to other people undergoing stressful and joyful life. Our participants were of the view that they search for both logical and emotional premises to embrace friends' problems since the activation of empathy in their minds drives them to act like this. Fundamentally, empathy enables us to perceive other people's feelings on emotional ground. In this capacity, our participants cited the need for understanding, in other words perceiving, others' problems emotionally. Affective empathy of the participants perpetuates their responses to another person's feelings (Bell, 2018). Yet such an approach is identified as the inherent quality that allows a person to experience another's emotions. Batson (2009), pertinently, featured this as compassionate empathy that leads a person to understand others' feelings with them and adequately offer help for them. Finally, the mirror neuron plays a vital role to place the participants in others' situations. However, our participants cited ‘logic’ as a ‘determiner’ to apprehend their friends' problems. Barrett-Lennard (1962) dubbed empathy as a human instinct that compels individuals to internalize another's perspective of the world. Our participants apply logic to carefully embrace the problem since empathy acts as a bridge to connect the person in assistance and the person in suffering to feel safe and understood. To explain, issues like a break-up in a love-relationship, a common phenomenon in our context has to be carefully addressed with the application of logic to understand the extent to which one is compatible with his or her partner. A case like this requires logic to offer psychological hugs or counsel, given that fueling the emotion instead of logical explanation might be more devastating, in other words suicidal, for the person in problem.

Furthermore, we administered a question in the light of participants' empathetic stance subject to expediting their social point of view on the necessity of valuing others' time as an act of empathy. The study documented that to sustain social balance and communication, time management is an excessively intrusive tool in one's mind. In that capacity, the empathy that students developed through classroom input plays a pivotal role in embracing the need for valuing others' time. The context of our study remains featured in the hectic lives of the citizens. Ranging from lower class to higher class, people experience severely busy schedules that typically lower the patience of them. Given the prevalence of such reality, a significant sign of being empathetic is to be a good manager of time that not only satisfies self but also acts as a symbol of respect for others. After that, our participants also shed light on the importance of listening to others as an act of empathy. Taking the effectiveness of communication and teamwork into account, and intending to understand others' perspectives, they highlighted the strength of listening to others. Gentry et al. (2007) advocated such a view with the additional comment that paying attention is highly required to address not only the verbal cues but also the nonverbal cues to read the emotion expressed through every word. That is how it becomes easier to apprehend others' perspective that is mandatory in building teamwork skills and effective communication. Cunico et al. (2012) also claimed that effective communication has been inclusive to empathy, which is also commensurate with our participants reporting that these two are correlated. Therefore, the empathy training infused in the classroom has been perceived as instrumental to the successful orientation of the students to empathy and its application.

Added to these, the participants of the study admitted that telling lies is sometimes important to maintain interpersonal relationships. They also accepted it as a tool for motivating a depressed friend in conjunction with identifying it as an act of practicing empathy. In our context, people are not ready to listen to the truth that is not linear to their favors. Typically, they have not been characterized by the mindset to accept any kind of constructive feedback or criticism. Even in the professional field or workplace, colleagues have not been cognitively ready to accept any kind of constructive feedback that might open new avenues concerning their career or promote themselves. As such, the culture of prescription has been inapplicable to our context. Being sufficiently cognizant about such mental constructs, our participants legitimized telling lies to maintain social bonding. Most importantly, participants were the proponent of articulating supportive words to boost a person suffering from depression, although the words were not real or true at all. Empathy, which empowers someone to embrace others' anger or confusion (Rogers, 1957), created the mental constructs of our participants in the way that prohibit themselves to utter any word that might aggravate someone's mood, and eventually the interpersonal relationships. Taking theoretical ground into account, cognitive empathy – that equips people with thoughtful approach and reasoning (Bodenhorn and Starkey, 2005) – underpinned our participants' action to embark on telling lies sometimes to avoid any disaster in terms of social relationships. Empathy for them remains a protective factor that drove them to behave technically when dealing with a person undergoing depression (Jolliffe and Farrington, 2004).

4. Conclusion

Empathy shapes the humanitarian values in students. It is not only essential to ensure an acute interpersonal relationship in academia, but also it entails meaningful implications in social life. We drew a vignette of our context that has been suffering from murder, assault, kidnapping, abuse, and rape, severely deteriorating the habitats for living. In a country like this, empathy-training must be institutionalized to appease violations. The purpose of this article has not been associated with advertising what we do in our language classrooms but to inform the world as to how we have been approaching to deal with the national crisis within our capacity. We continued speaking and listening practices in the language classroom to infuse empathy among first-year students of the university. Teaching and cultivating empathy in the listening classroom have been observed in Russia (e.g., Stebletsova and Torubarova, 2017). We firmly believe that if we start incorporating the activities related to empathy, our students would tend to be humanitarian in the process. We chose the very first semester to put empathy into mind and practice since the students have the major part of life left to show empathy in various stages like academic journey, professional and social life. Therefore, we took the chance to fulfill their fresh and void minds with empathy.

Declarations

Author contribution statement

I. Z Numanee: Conceived and designed the experiments, Performed the experiments, Analyzed and interpreted the data, Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data, Wrote the paper N. Zafar: Performed the experiments, Analyzed and interpreted the data, Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data, Wrote the paper A. Karim: Analyzed and interpreted the data, Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data, Wrote the paper S. A. M. M Ismail: Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data, Wrote the paper.

Funding statement

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interest statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

References

- Alford C.F. Mirror neurons, psychoanalysis, and the age of empathy. Int. J. Appl. Psychoanal. Stud. 2016;13(1):7–23. [Google Scholar]

- Ançel G. Developing empathy in nurses: an inservice training program. Arch. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2006 doi: 10.1016/j.apnu.2006.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett-Lennard G.T. Dimensions of therapist response as causal factors in therapeutic change. Psychol. Monogr.: General Appl. 1962;76(43):1–36. [Google Scholar]

- Baron-Cohen S., Wheelwright S. The empathy quotient: an investigation of adults with Asperger syndrome or high functioning autism, and normal sex differences. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2004 doi: 10.1023/b:jadd.0000022607.19833.00. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bas-Sarmiento P., Fernández-Gutiérrez M., Baena-Baños M., Romero-Sánchez J.M. Efficacy of empathy training in nursing students: a quasi-experimental study. Nurse Educ. Today. 2017;59:59–65. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2017.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batson C.D. These things called empathy. In: Decety J., Ickes W., editors. The Social Neuroscience of Empathy. MIT Press; Cambridge , MA: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Batt-Rawden S.A., Chisolm M.S., Anton B., Flickinger T.E. Teaching empathy to medical students: an updated, systematic review. Acad. Med. 2013 doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e318299f3e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell H. Creative interventions for teaching empathy in the counseling classroom. J. Creativ. Ment. Health. 2018;13(1):106–120. [Google Scholar]

- Bodenhorn N., Starkey D. Beyond role-playing: increasing counselor empathy through theater exercises. J. Creativ. Ment. Health. 2005;1(2):17–27. [Google Scholar]

- Bosse H.M., Schultz J.H., Nickel M., Lutz T., Möltner A., Jünger J., Huwendiek S., Nikendei C. The effect of using standardized patients or peer role play on ratings of undergraduate communication training: a randomized controlled trial. Patient Educ. Counsel. 2012;87(3):300–306. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2011.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown H.D. Vol. 4. Longman; New York: 2000. (Principles of Language Learning and Teaching). [Google Scholar]

- Brunero S., Lamont S., Coates M. A review of empathy education in nursing. Nurs. Inq. 2010;17(1):65–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1800.2009.00482.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryman A. Oxford University Press; Oxford, UK: 2012. Social Research Methods. [Google Scholar]

- Burke David. Empathy in sexually offending and nonoffending adolescent males. J. Interpers. Violence. 2001 [Google Scholar]

- Bush C.A., Mullis R.L., Mullis A.K. Differences in empathy between offender and nonoffender youth. J. Youth Adolesc. 2000;29(4):467–478. [Google Scholar]

- Chen D., Lew R., Hershman W., Orlander J. A cross-sectional measurement of medical student empathy. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2007;22(10):1434–1438. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0298-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen L., Manion L., Morrison K. Routledge; London, UK: 2013. Research Methods in Education. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell J.W. third ed. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2013. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell J.W., Poth C.N. fourth ed. Sage; Los Angeles, CA: 2017. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches. [Google Scholar]

- Cunico Laura, Sartori Riccardo, Marognolli Oliva, Meneghini Anna M. Developing empathy in nursing students: a cohort longitudinal study. J. Clin. Nurs. 2012 doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2012.04105.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalton R.F., Sundblad L.M., Hylbert K.W. An application of principles of social learning to training in communication of empathy. J. Counsel. Psychol. 1973;20(4):378. [Google Scholar]

- De Vignemont F., Singer T. The empathic brain: how, when and why? Trends Cognit. Sci. 2006;10(10):435–441. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2006.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N., Strayer J. CUP Archive; 1990. Empathy and Its Development. [Google Scholar]

- Elliott R., Watson J.C., Goldman R.N., Greenberg L.S. Learning emotion-focused therapy: the process-experiential approach to change. Am. Psychol. Assoc. 2004 [Google Scholar]

- Elliott Robert, Bohart Arthur C., Watson Jeanne C., Greenberg Leslie S. Empathy. Psychotherapy. 2011 doi: 10.1037/a0022187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferdous T., Karim A. Working in groups outside the classroom: affective challenges and probable solutions. Int. J. InStruct. 2019;12(3):341–358. [Google Scholar]

- Fine V.K., Therrien M.E. Empathy in the doctor-patient relationship: skill training for medical students. J. Med. Educ. 1977;52(9):752–757. doi: 10.1097/00001888-197709000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franzese P.A. Vol. 47. Seton Hall L. Rev.; 2016. The power of empathy in the classroom; p. 693. [Google Scholar]

- Gallese V., Eagle M.N., Migone P. Intentional attunement: mirror neurons and the neural underpinnings of interpersonal relations. J. Am. Psychoanal. Assoc. 2007;55(1):131–175. doi: 10.1177/00030651070550010601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gay L.R., Mills G.E., Airasian P.W. Pearson; Upper Saddle River, NJ: 2011. Educational Research: Competencies for Analysis and Applications. [Google Scholar]

- Gentry William A., Weber Todd J., Sadri Golnaz. A Center for Creative Leadership White Paper; 2007. Empathy in the workplace: a tool for effective leadership. [Google Scholar]

- Gladstein G.A., Feldstein J.C. Using film to increase counselor empathic experiences. Couns. Educ. Superv. 1983;23(2):125–131. [Google Scholar]

- Goleman D. Bantam Dell; New York: 2006. Emotional Intelligence. [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg L.S., Goldman R.L. Training in experiential therapy. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1988;56(5):696. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.56.5.696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He S. 2nd International Conference on Judicial, Administrative and Humanitarian Problems of State Structures and Economic Subjects (JAHP 2017) Atlantis Press; 2017, September. Metaphor and education-analyzing the role of cultural empathy in teaching Chinese as a foreign language. [Google Scholar]

- Herrera S., Murry K. Pearson; Boston: 2005. Mastering ESL and Bilingual Methods. [Google Scholar]

- Hogan R. Development of an empathy scale. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1969;33(3):307. doi: 10.1037/h0027580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inkster B., Sarda S., Subramanian V. An empathy-driven, conversational artificial intelligence agent (Wysa) for digital mental well-being: real-world data evaluation mixed-methods study. JMIR MHealth UHealth. 2018;6(11) doi: 10.2196/12106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jolliffe D., Farrington D.P. Empathy and offending: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2004;9(5):441–476. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y., Wang J. A study of cultural empathy in foreign language teaching from the perspective of cross-cultural communication. Theor. Pract. Lang. Stud. 2018;8(12):1664–1670. [Google Scholar]

- Laird L. Empathy in the classroom: can music bring us more in tune with one another? Music Educ. J. 2015;101(4):56–61. [Google Scholar]

- Marcus R.F., Gray L., Jr. Close relationships of violent and nonviolent African American delinquents. Violence Vict. 1998;13(1):31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marx S., Pray L. Living and learning in Mexico: developing empathy for English language learners through study abroad. Race Ethn. Educ. 2011;14(4):507–535. [Google Scholar]

- Meshcheryakov B.G., Zinchenko V.P. Olma-press: Russian; Moscow: 2004. Bolshoi Psihologichesky Slovar [Big Psychological Glossary] [Google Scholar]

- Nunan David. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 1992. Research Methods in Language Learning. [Google Scholar]

- Özcan Neslihan, Bilgin Hülya, Eracar Nevin. The use of expressive methods for developing empathic skills. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 2011 doi: 10.3109/01612840.2010.534575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen R. Empathy development in medical education–a critical review. Med. Teach. 2010;32(7):593–600. doi: 10.3109/01421590903544702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Punch K. Introduction to Social Research: Qauntitative and Qualitative Approaches. In: 2nd Ed, editor. Sage; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers C.R. The necessary and sufficient conditions of therapeutic personality change. J. Consult. Psychol. 1957;21(2):95–103. doi: 10.1037/h0045357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Şahin Mustafa. An investigation into the efficiency of empathy training program on preventing bullying in primary schools. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro J., Morrison E., Boker J. Teaching empathy to first year medical students: evaluation of an elective literature and medicine course. Educ. Health. 2004;17(1):73–84. doi: 10.1080/13576280310001656196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer J. Decline in empathy in medical education: how can we stop the rot? Med. Educ. 2004;38(9):916–918. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2004.01965.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stebletsova A.O., Torubarova I.I. Empathy development through ESP: a pilot study. J. Educ. Cultur. Psychol. Stud. (ECPS J.) 2017;(16):237–249. [Google Scholar]

- Sulzer S.H., Feinstein N.W., Wendland C.L. Assessing empathy development in medical education: a systematic review. Med. Educ. 2016;50(3):300–310. doi: 10.1111/medu.12806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Manen M. Care-as-worry, or “don’t worry, be happy”. Qual. Health Res. 2002;12(2):262–278. doi: 10.1177/104973202129119784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanaerschot G. Empathic resonance and differential experiential processing: an experiential process–directive approach. Am. J. Psychother. 2007;61(3):313–331. doi: 10.1176/appi.psychotherapy.2007.61.3.313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Washburn G.N. Alone, confused, and frustrated: developing empathy and strategies for working with English language learners. Clear. House A J. Educ. Strategies, Issues Ideas. 2008;81(6):247–250. [Google Scholar]

- Yuen J.K.Y., See C.Y.H., Lum C.M., Cheung T.K., Wong W.T. Asia Pacific Medical Education Conference (APMEC) Centre for Medical Education (CenMED), Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore; 2019. Empathy training for medical students through A blended learning communication skills training programme: a mixed-methods study. [Google Scholar]

- Zembylas M. Pedagogies of strategic empathy: navigating through the emotional complexities of anti-racism in higher education. Teach. High. Educ. 2012;17(2):113–125. [Google Scholar]