The rapidly evolving global pandemic from the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 and its resulting coronavirus disease (COVID-19) has sowed confusion regarding actual risk to patients and health care workers, presenting symptoms, what actions health care workers should take, and when to act.1 A global Biogen management meeting on February 27, 2020, in Boston, purportedly resulted in ≥70 linked infections within 2 weeks, which was amplified by broader dissemination from postmeeting travel.2 This single event likely substantially contributed to viral spread within Massachusetts and transmission to other states. The global spread of the virus; high reported mortality in China, Italy, and other countries; and other events raise important questions for our disciplines. How much more dangerous is this than influenza and similar viruses? Should we stop elective procedures? Are there specific symptoms relevant to gastroenterologists and hepatologists? Should we hold in-person research and clinical meetings? How should geographic regions without many cases respond? As gastroenterologists, and as an epidemiologist and a basic scientist, we have followed recent events closely.

You are a leader within your health care setting, community, and family; you can influence actions that will save lives and decrease the potential human and economic damage from COVID-19.

In this commentary, we cover current knowledge about COVID-19, information particularly relevant to gastroenterology/hepatology, and actions that can be effective.

COVID-19 Is a Clear Danger to Public Health

-

•

COVID-19 is global and is now considered a pandemic; as of March 15, it is in >150 countries.3

-

•

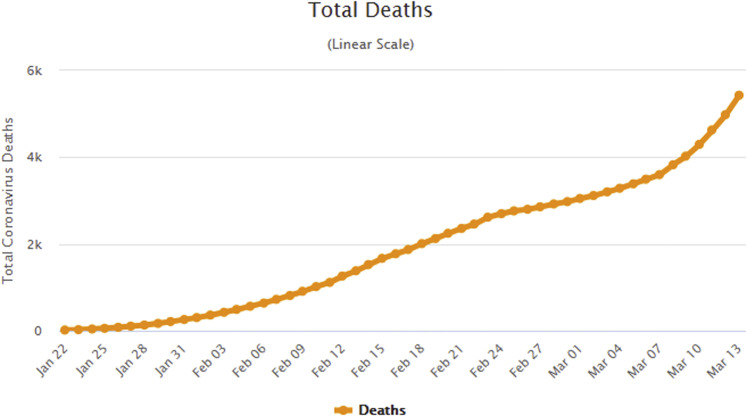

The virus is readily transmissible. In China, it spread from a single city to the entire country within 30 days.4 The total number of both cases and deaths outside of China, as of March 13, were growing almost exponentially (Figure 1 ).5 In Wuhan, it was estimated that, initially, each infected patient transmitted the virus to an additional 2.3 individuals, comparable with the 1918 influenza pandemic; in contrast, influenza transmits to 1.3 individuals.6

-

•

Infectivity can precede discernible symptoms. Because of this, simple postsymptom isolation alone is ineffective in halting transmission.

-

•

Published cases reported markedly underestimate the number of infected people. The paucity of test kits, lack of population-level surveillance, and presence of infection among minimally symptomatic people means published case counts underestimate actual infections, many-fold.4

-

•

The population lacks substantial immunity. Because of this, many of those exposed may become infected.

-

•

It will cause many deaths, including among health care providers. The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) noted the proportion of infected people to those who died (case-fatality rate) was 3.5% in China (0.8% excluding Hubei Province) and 0.6% on a cruise ship, suggesting a likely range of 0.25–3.00%.7 In contrast, fatality rates for influenza hover around 0.1%. Assuming that early rates are overestimates, given undertesting of milder cases, a 0.5% mortality rate in a country the size of the United States, if 50% are ultimately infected, would result in >800,000 deaths.8

Figure 1.

Total global reported deaths from COVID (from: www.worldometers.info).

COVID-19 Can Result in Gastrointestinal Symptoms and Viral Shedding in Stool

Gastrointestinal symptoms such as vomiting, diarrhea, and abdominal pain have been reported in approximately 20% of patients with COVID-19, including among patients with minimal respiratory symptoms.9 In addition, viral RNA is detectable in stool in many infected patients. Stool shedding can persist after viral clearance from respiratory specimens; however, whether this is meaningfully infectious and if there is any substantial fecal–oral transmission is unknown.10 Patients also can experience elevations in liver transaminases, similar to other systemic viral infections. Stool assays are not recommended or available at this time; however, this knowledge may recommend testing for appropriate patients with predominantly gastrointestinal symptoms in communities with known viral transmission.

Action Is Effective

Clinicians and Researchers Can Have an Impact

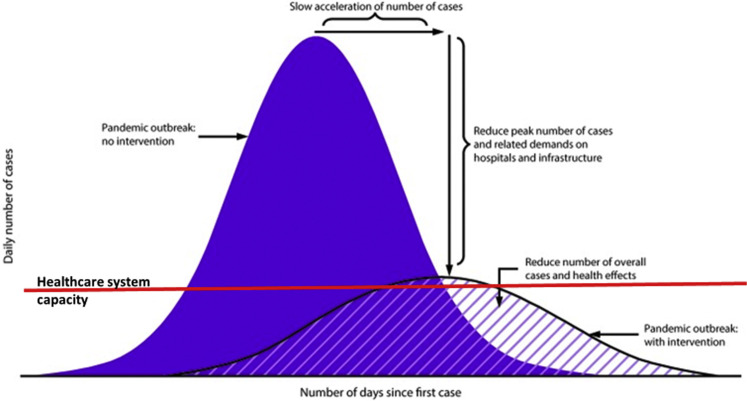

A key current recommendation is to slow transmission through mitigation efforts that decreased person-to-person contacts and improve infection control. Commonly referred to as “flattening the curve,” this strategy may lead to few total cases or, at the minimum, spread cases out over time, allowing greater alignment between the number of ill patients at any given time and available health care resources, such as ventilators, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation units, and intensive care units beds (Figure 2 ).

Figure 2.

Flattening the curve: effects of interventions to decrease transmission. (Adapted from www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5837128/.)

Emerging Data Indicate This Approach Works

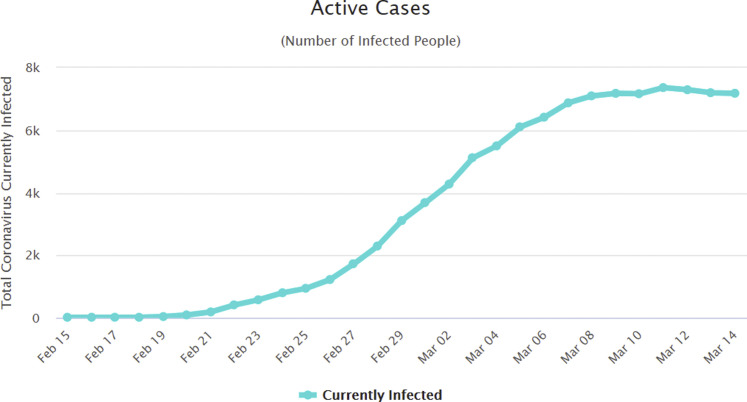

A modeling study suggested that, in China, travel restrictions and the practice of “social distancing” (decreasing the number and proximity of contacts between people to decrease opportunities for transmission) changed the daily reproduction number from 2.35 to 1.05 within 1 week.11 Similar data from South Korea, which instituted relatively broad-scale testing, also suggested a rapid decrease in new cases diagnosed (Figure 3 ). The broader the implementation, the greater the impact; this is why France recently shut down nonessential businesses, including restaurants and cafes.

-

•

Change in-person meetings to teleconferences. Most clinical and research collaborations are highly amenable to remote communications; numerous integrated (eg, Teams in Office 365) and web-based services (Zoom, Go to Meeting, etc) are easily accessible. Changing small2 , 3 and larger research, clinical, and educational meetings to video conferences preserves social interactions and productivity, while markedly decreasing social contacts.

-

•

Minimize nonessential travel, especially to gatherings. 12 The Boston Biogen meeting described in the introduction, is a poignant example. Another is the complex single-person effects on transmission suggested by an attorney in New Rochelle, New York, who likely infected multiple people throughout the community before diagnosis. These examples demonstrate how a small number of undiagnosed individuals with broad social contacts can rapidly amplify viral infections.13

-

•

Change in-person patient visits to telehealth visits, where appropriate. Many office visits are primarily for interviews and exchange of information. Telemedicine is appropriate and covered by insurance for many initial and follow-up visits; it markedly decreases person-to-person contacts that occur throughout the travel from home to office.14

-

•

Delay nonessential (elective) procedures in areas with reported cases. In regions with reported cases, strongly consider deferring nonessential procedures. A single screening endoscopic examination may create encounters at the pharmacy (bowel preparation), office (preparation instructions), preprocedure transportation, procedure registration, preoperative nursing, intraprocedure personnel, postoperative care, and postprocedure transportation.

-

•

Screen patients for symptoms. Patients coming for office or procedural visits typically receive previsit phone calls. Use these calls to screen for potential viral symptoms and to inform relevant steps, such as postponing nonurgent visits or, if the visit is urgent, plan relevant intravisit and perivisit protective measures.

-

•

Monitor local conditions and recommendations. Active infections and community-based transmission likely precede diagnosed cases; thus, if there are diagnosed cases in your region, there likely are many more people with active infections. Your actions can change with local disease prevalence (see the CDC mitigation recommendations).

-

•

Continue patients’ current medications. It can be difficult to balance concerns about theoretical benefits with known harms. Patients on medications altering their immune systems, such as biologic agents, methotrexate, and azathioprine, are understandably concerned regarding their risk, including whether they should stop or decrease their medications. The CDC does not currently list this group as high risk; the CDC website is an excellent source for evolving recommendations.15 There are few data suggesting that otherwise healthy nontransplant patients on such medications are at a substantially increased risk of either acquiring coronavirus (or similar viruses such as influenza) or, if infected, having a more severe disease course. In contrast, there are known potential harms regarding disease flare, need for steroids (which impose greater infectious risk), and hospitalization with medication discontinuation. Thus, patients should continue their current medications and, if experiencing any infectious symptoms, consult with their physician regarding whether to modify their medication regimens.

-

•

Medical personnel and staff should follow infectious precautions. They should stringently adhere to recommendations regarding decreasing spread, such as handwashing and minimizing touching of face and hair.

-

•

Develop plans now for decreases in personnel. Clinics and laboratories should plan for possible illnesses among critical personnel, and protocols to minimize adverse impacts.

-

•

Frequently check updated recommendations. The following are excellent, official, frequently updated resources for health care providers and patients.

-

•

CDC recommendations for community mitigation: www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/downloads/community-mitigation-strategy.pdf

-

•

CDC recommendations for infection control within health care settings: www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/infection-control/control-recommendations.html

-

•

World Health Organization recommendations and updates: www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019

-

•

Guidance for high-risk groups: www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/specific-groups/high-risk-complications.html

-

•

Patient information about masks and infection control: www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/advice-for-public

-

•

Addressing myths about coronavirus: www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/advice-for-public/myth-busters

-

•

General information, including emerging treatments: www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/index.html; and www.uptodate.com/contents/coronaviruses;

-

•

Latest research and recommendations from the American Gastroenterological Association (see COVID-19 tab at top left): www.gastrojournal.org/

Figure 3.

Numbers of active patients with infections in South Korea (from: www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/country/south-korea/).

We Can Decrease the Impact of the Current Pandemic

People will look to you for leadership, policies, and advice. These are practical, evidence-based steps you can recommend now and/or implement directly with your teams and colleagues.

THE AGA is actively developing consensus recommendations; we look forward to these and other information from our medical societies and public health leaders.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest The authors disclose no conflicts.

References

- 1.World Health Organization Naming the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) and the virus that causes it. www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/technical-guidance/naming-the-coronavirus-disease-(covid-2019)-and-the-virus-that-causes-it Available:

- 2.Woods A. Massachusetts declares state of emergency as coronavirus spreads. https://nypost.com/2020/03/11/massachusetts-declares-state-of-emergency-as-coronavirus-spreads/ Available:

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Coronavirus disease 2019: world map. www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/cases-updates/world-map.html?CDC_AA_refVal=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.cdc.gov%2Fcoronavirus%2F2019-ncov%2Flocations-confirmed-cases.html Available:

- 4.Wu Z., McGoogan J.M. Characteristics of and Important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: summary of a report of 72 314 cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/2762130 Available: [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Worldometer Coronavirus cases. www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/coronavirus-cases/#case-tot-outchina Available:

- 6.Coburn B.J., Wagner B.G., Blower S. Modeling influenza epidemics and pandemics: insights into the future of swine flu (H1N1) BMC Med. 2009;7:30. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-7-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wilson N., Kvalsvig A., Telfar Barnard L., Baker M.G. Case-fatality estimates for COVID-19 calculated by using a lag time for fatality. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020;26(6) doi: 10.3201/eid2606.200320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.US Census Bureau U.S. and world population clock. www.census.gov/popclock/ Available:

- 9.Gu J., Han B., Wang J. COVID-19: Gastrointestinal manifestations and potential fecal-oral transmission. Gastroenterology. 2020 Mar 3 doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.02.054. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xiao F., Tang M., Zheng X. Evidence for gastrointestinal infection of SARS-CoV-2. Gastroenterology. 2020 Mar 3 doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.02.055. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cascella M., Rajnik M., Cuomo A. Features, evaluation and treatment coronavirus (COVID-19) www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK554776/ [PubMed]

- 12.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Travel. www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/travelers/index.html

- 13.Goldstein J., Salcedo A. For 4 days, the hospital thought he had just pneumonia. It was coronavirus. www.nytimes.com/2020/03/10/nyregion/coronavirus-new-rochelle-pneumonia.html Available:

- 14.Siegel C.A. Transforming gastroenterology care with telemedicine. Gastroenterology. 2017;152:958–963. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.01.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Coronavirus disease 2019. www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/specific-groups/high-risk-complications.html Available: