Abstract

Translation of a genetic codon without a cognate tRNA gene is affected by both the cognate tRNA availability and the interaction with non-cognate isoacceptor tRNAs. Moreover, two consecutive slow codons (slow di-codons) lead to a much slower translation rate. Calculating the composition of host specific slow codons and slow di-codons in the viral protein coding sequences can predict the order of viral protein synthesis rates between different virus strains.

Comparison of human-specific slow codon and slow di-codon compositions in the genomes of 590 coronaviruses infect humans revealed that the protein synthetic rates of 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) and severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus (SARS-CoV) may be much faster than other coronaviruses infect humans. Analysis of host-specific slow codon and di-codon compositions provides links between viral genomic sequences and capability of virus replication in host cells that may be useful for surveillance of the transmission potential of novel viruses.

Keywords: 2019-nCoV, Host-specific slow codons, Host tRNA genes

Introduction

No organism has a full set of tRNA species for all 61 amino acid-encoded codons.1 Codons without cognate tRNA gene can be referred to as slow codons of the organism. These codons are organism specific codons because different organisms have different tRNA gene compositions. For example, 13 amino acid-encoding codons have no cognate tRNA genes in the human genome. Studies have revealed by ribosomal profiling experiments that translation of codons by rare tRNAs and non-cognate isoacceptor tRNAs (by wobble base pairing of codons and tRNAs) reduces translation efficiency2 , 3 ,.4 Moreover, it has been reported that the efficiency of translating a particular codon is affected by the nature of the immediately adjacent codons.5 , 6 Two consecutive slow codons (slow di-codons) lead to a much slower translation rate. Conversely, coding sequences (CDSs) with low composition of slow codons and slow di-codons may possess fast translation rates.

Translation of viral proteins is completely dependent on the translation machinery of host cells. Therefore, the proportions of host-specific slow codons and slow di-codons in the viral CDSs can be used to predict the order of viral protein synthesis rates between different viruses of different genera, serotypes, and strains.

In this study, compositions of human slow codon and slow di-codon in genomes of coronaviruses isolated from human hosts were analyzed to evaluate the differences of translation efficiency of viral proteins in the human host cells.

Material and methods

Data collection

The CDSs of 590 coronavirus complete (full-length) genomes isolated from human hosts (25 human coronavirus 229 E (HCoV-229 E), 60 human Coronavirus NL63 (HCoV-NL63), 39 human coronavirus HKU1 (HCoV-HKU1), 139 human coronavirus OC43 (HCoV-OC43), 42 Severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus (SARS-CoV), 123 Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS-CoV), 34 Wuhan seafood market pneumonia virus (2019-nCoV)) and 128 unclassified coronaviruses (Other) were retrieved from the Virus Pathogen Resource (ViPR, https://www.viprbrc.org/)7 and analyzed in this study. The information of tRNA genes in the human genome were obtained from the Genomic tRNA Database (GtRNAdb, http://gtrnadb.ucsc.edu/).1

Data analysis

Thirteen amino acid-encoding codons (ACC, CCC, CGC, CTC, GCC, GGT, GTC, TCC, AGT, GAT, CAT, TGT, TTT) without cognate tRNA genes in the human genome were referred as human slow codons. The 169 human slow di-codons were produced from combinations of the 13 slow codons (GTCAGT, GATCAT, TGTTGT, TCCCCC, TTTTTT, GATAGT, GCCCGC, AGTGGT, GCCTGT, GATCCC, AGTAGT, TTTTGT, CCCCAT, CATGGT, TCCGGT, TCCGCC, CATTTT, AGTGAT, GTCGGT, CTCAGT, TGTGTC, GCCTCC, GTCCAT, GTCCTC, GATGTC, ACCCAT, ACCGGT, CGCCTC, TTTCTC, CATGTC, ACCTTT, CGCCGC, TTTCAT, GCCGTC, AGTTGT, CCCCCC, CTCGTC, ACCGAT, CTCACC, CGCGAT, CATACC, CTCGCC, ACCTCC, TGTCCC, TTTGGT, AGTCTC, CTCCAT, CCCTGT, AGTACC, GCCAGT, GTCCGC, TGTTCC, TGTGAT, CATCTC, TCCTGT, TTTGTC, GCCGAT, ACCCCC, GGTCAT, AGTCAT, CGCGTC, GGTTCC, ACCGCC, GGTTTT, CTCGGT, GCCGCC, GTCACC, GCCCTC, TCCACC, AGTCCC, CCCGCC, CGCAGT, ACCTGT, TGTCTC, AGTTCC, TGTTTT, GTCTCC, GCCCCC, CTCTCC, ACCCGC, TGTCGC, GATCGC, TCCTTT, CGCTGT, GGTGAT, GTCTTT, CATGAT, TTTGAT, GTCTGT, GTCGAT, TCCCGC, CATTCC, CATCCC, CTCCGC, ACCCTC, AGTGTC, CATAGT, GCCTTT, AGTCGC, GTCCCC, AGTGCC, CCCGTC, GATTGT, GCCACC, CGCGCC, CGCACC, GGTTGT, GATTTT, GGTCCC, TGTAGT, CCCTCC, TTTACC, CTCGAT, CGCCCC, CCCCGC, GGTCGC, GGTAGT, CCCTTT, TCCCTC, ACCAGT, GGTGGT, GATGGT, ACCGTC, TTTGCC, CCCACC, CGCTCC, TCCGAT, GATACC, TCCAGT, TGTGCC, GGTCTC, CTCTTT, CGCCAT, GATGCC, GGTGTC, GATTCC, GATCTC, CATGCC, GGTACC, CGCGGT, CCCGGT, TCCCAT, CCCGAT, CTCCTC, TTTAGT, CATTGT, CTCTGT, TGTGGT, CATCAT, GCCCAT, GTCGCC, TCCTCC, GGTGCC, TCCGTC, CTCCCC, TGTACC, GTCGTC, TTTCGC, CCCCTC, CGCTTT, CCCAGT, GCCGGT, TTTCCC, CATCGC, TGTCAT, GATGAT, ACCACC, AGTTTT, TTTTCC). Given a viral CDS, the proportion of human slow codons Ct was computed by the formula.1

| (1) |

where N C is the number of human slow codons present in each viral CDS. L is the total number of codons of each viral CDS (length of the amino acid sequence). n is the number of CDSs in a coronavirus genome. The proportion of human slow di-codons DiC was computed by the formula.2

| (2) |

where N DC is the number of human slow di-codons present in each viral CDS. L is the total number of codons of each viral CDS (length of the amino acid sequence). n is the number of CDSs in a coronavirus genome. Both of the ranges of Ct and DiC are between 0 and 1. Data manipulation, processing and codon counting were performed using Python scripts written by the author. The heatmap, scatter plots and distributions of Ct and DiC values were plotted using the ggplot2 package in R (the R package for statistical computing). Phylogenetic analysis was performed using the Clustal X 2.0 software.8

Results

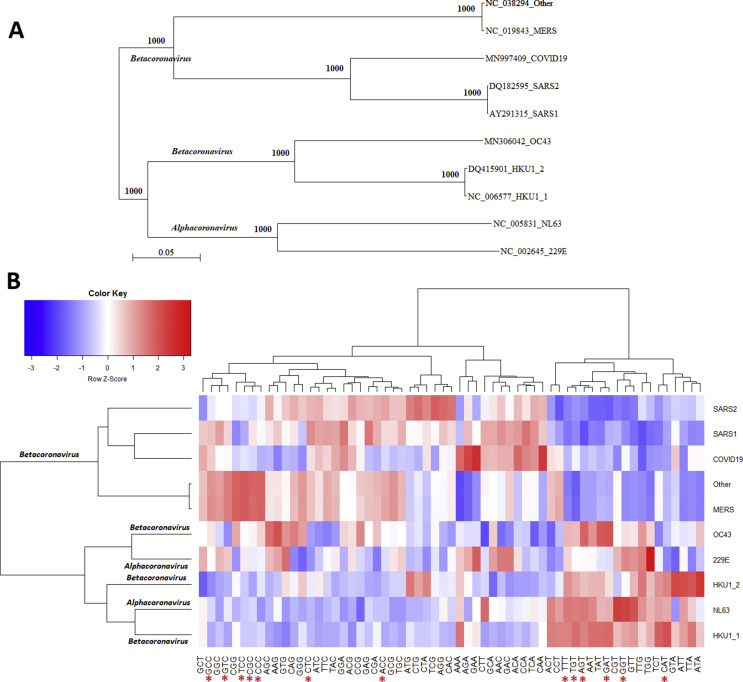

In total, CDSs of 590 coronavirus complete genomes were collected from 8 coronavirus groups (229 E, NL63, HKU1, OC43, SARS, MERS, SARS-CoV-2 and unclassified) which can infect the human hosts. According to variations of codon compositions, the HKU1 and SARS were divided into 2 subgroups. Phylogenetic analysis of full-length genomic sequences of the representative coronavirus from each group is shown in Fig. 1 A. Analysis results of the genetic codon compositions of 8 coronavirus groups (and subgroups) infect humans are shown in Fig. 1B. Comparison of Fig. 1A and B shows that the analysis based on the phylogenetic tree and viral genetic codon compositions are not completely consistent. For example, although NL63 and HKU1 belong to alpha and beta coronaviruses, respectively, they exhibit similar codon compositions. These results indicate that the analysis of genetic codon composition provides novel information that cannot be revealed in the phylogenetic analysis. It is interesting that the codon compositions of NL63 and HKU1 exhibit an opposite pattern with the codon compositions of MERS-CoV, SARS-CoV, and 2019-nCoV. Six human slow codons (CAT, GGT, GAT, TGT, AGT, and TTT) exhibit higher proportion in the NL63 and HKU1 groups. In contrast, only 2 human slow codons (ACC, and CTC) exhibit higher proportion in the MERS-CoV, SARS-CoV, and 2019-nCoV groups.

Fig. 1.

(A) Phylogenetic analysis of full-length genomic sequences of the representative coronaviruses infect human hosts. The number of each branch obtained from 1000 bootstrapping was shown. Accession numbers indicate the representative genomic sequences used in this analysis. (B) Comparison of genetic codon compositions of 8 coronavirus groups (and subgroups) infect human hosts. 229 E: human coronavirus 229 E. NL63: human coronavirus NL63. HKU1: human coronavirus HKU1. OC43: human coronavirus OC43. SARS: severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus (SARS-CoV), MERS: middle east respiratory syndrome (MERS-CoV). COVID19: Wuhan seafood market pneumonia virus (2019-nCoV). Other: unclassified coronaviruses. Red stars “∗” indicate the 13 human specific slow codons.

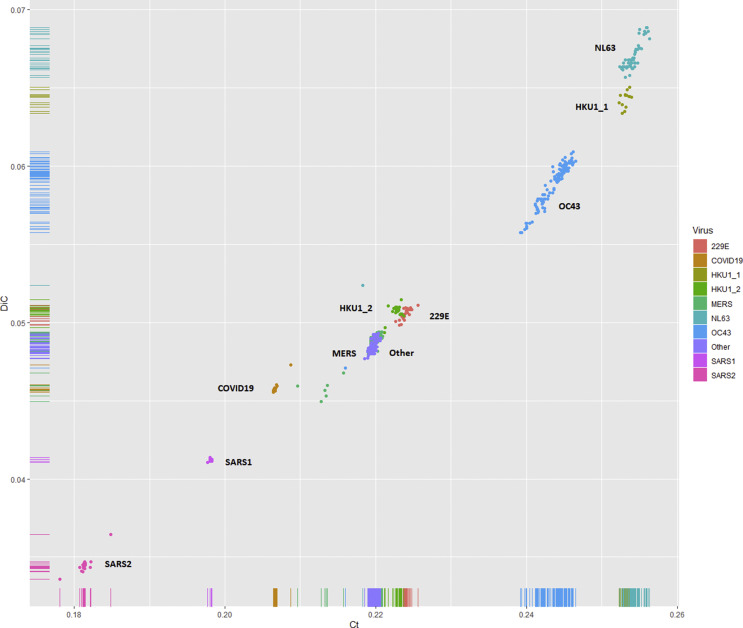

The distribution of overall proportions of human slow codons and slow di-codons in the coding sequences from 590 coronaviruses isolated from human hosts is shown in Fig. 2 . The order of overall proportions of human slow codons and slow di-codons is SARS2 < SARS1 < SARS-CoV-2 < unclassified ≅ MERS < HKU1_2 ≅ 229 E < OC43 < HKU1_1 < NL63. These results indicate that the SARS-CoV and 2019-nCoV may have higher protein synthetic rates than other coronavirus groups which infect humans.

Fig. 2.

Distribution of proportions of human slow codons and slow di-codons in the coding sequences from 590 coronaviruses isolated from human hosts. 229 E: Human coronavirus 229 E. NL63: Human coronavirus NL63. HKU1: Human coronavirus HKU1. OC43: Human coronavirus OC43. SARS: severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus (SARS-CoV), MERS: middle east respiratory syndrome (MERS-CoV). COVID19: Wuhan seafood market pneumonia virus (2019-nCoV). Other: unclassified coronaviruses. Ct: overall proportions of 13 human specific slow codons. DIC: overall proportions of 169 human specific slow di-codons.

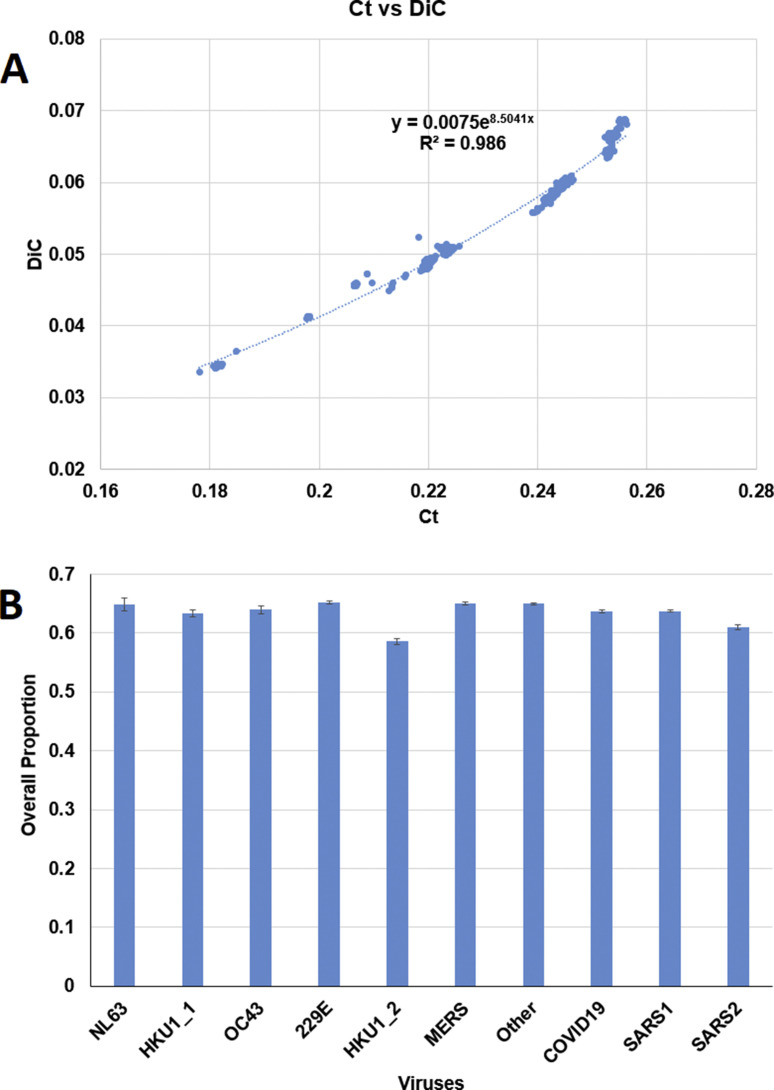

Two analysis were conducted to check if the observed phenomena are random events. First, regression of Ct and DiC values were performed. The R 2 values of regression of Ct and DiC values by exponential regression, polynomial regression, and linear regression are 0.986, 0.9844 and 0.9729, respectively. The result of exponential regression is shown in Fig. 3 A. The non-linear relationship between slow codon and slow di-codon compositions suggests the observed phenomena may be not random events. Second, the overall proportions of amino acids associated with human specific slow codons in viral proteins were computed. As shown in Fig. 3B, the order of the proportions of amino acids associated with human specific slow codons in viral proteins were not consistent with the order of overall proportions of human slow codons and slow di-codons in viral CDSs. These results suggest that lower proportions of human slow codons and slow di-codons are not completely due to lower demand of amino acids in viral proteins.

Fig. 3.

The relationship between Ct and DiC and overall proportions of amino acids associated with the 13 human specific slow codons. (A) The regression equation and R2 value of Ct and DiC values. Ct: overall proportions of the 13 human specific slow codons. DIC: overall proportions of the 169 human specific slow di-codons. (B) The overall proportions of amino acids associated with the 13 human specific slow codons in coronaviruses infect humans.

Discussion

SARS-CoV was the first pandemic caused by a coronavirus. The disease emerged in late 2002 in the Guangdong Province of China. During the epidemic in 2003, 8096 cases with 774 deaths occurred in 27 countries.9 For 2019-nCoV, over 24,552 confirmed cases and 492 deaths in 28 countries have been reported from mid-Dec. 2019 to February 4 2020. In contrast, the MERS-CoV outbreak, sporadic cases, small clusters, and large outbreaks have been reported in 27 countries, with over 2254 cases of the virus and over 800 deaths.10 The order of transmission rates (2019-nCoV and SARS-CoV > MERS-CoV > other coronaviruses infect humans) is consistent with the order of hypothetical protein synthetic rates (2019-nCoV and SARS-CoV > MERS-CoV > other coronaviruses infect humans) proposed in this study.

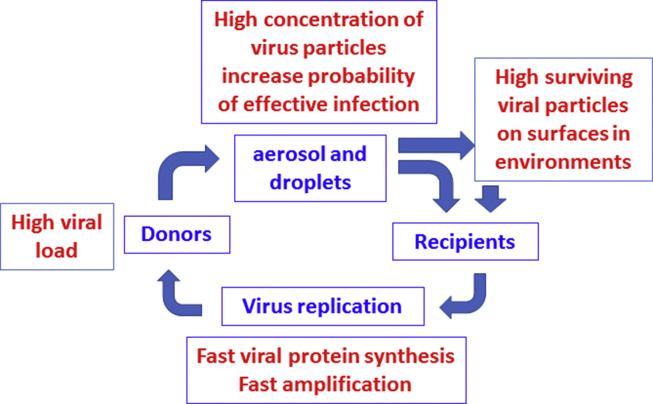

Herfst et al.11 propose a set of drivers facilitating human-to-human transmission of airborne pathogens with the aerosols and droplets as mediators in airspace between individuals (Fig. 4 ). First, the airborne pathogens are carried with aerosols, droplets, or particulate matter, such as PM2.5, and transported through the air from donor to recipient. Second, airborne pathogens usually exhibit a relatively low 50% infectious dose (ID50) value. A low concentration of pathogens is sufficient for infection in the respiratory tract of the recipients. Third, after infection of susceptible cells, pathogens may amplify at the site of deposition or are disseminated from the primary deposition site to peripheral tissues (secondary site), where additional amplification takes place. Fourth, eventually, the recipient becomes the donor, and pathogens are expelled from the exit site (usually the respiratory tract). High infectious loads of the pathogens re-emerge in the air to complete the transmission cycle. According to the 4 steps, viruses with high protein synthesis rates (as a consequence, replication rates) have great advantages to increase transmissibility. First, fast-replication viruses can produce aerosols, droplets, or particulate matter with high viral loads that increase the remaining percentage of surviving viruses in environments before reaching the recipients. Second, after viruses reach the recipients, the fast replication viruses have a higher chance of successful infection even the initial when infection dose is low. The finding of this study provides an explanation other than virus-host receptor interactions for fast transmissibility of 2019-nCoV. High transmissibility does not necessarily result in high fatality. Data has shown that the order of transmissibility is 2019-nCoV and SARS-CoV > MERS-CoV > other coronaviruses infect humans.

Fig. 4.

A proposed driving mechanism of human-to-human transmissibility enhanced by fast viral protein synthetic rate of airborne pathogenic viruses.

In conclusion, conventional phylogenetic analysis of viral genomic sequences is useful for tracking the origin of viruses. Analysis of host-specific slow codon and di-codon composition provides links between viral genomic sequences and capability of viral protein synthesis in host cells for prediction and surveillance of transmission potential of emerging novel viruses.

References

- 1.Chan P.P., Lowe T.M. GtRNAdb: a database of transfer RNA genes detected in genomic sequence. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:D93–D97. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dana A., Tuller T. Determinants of translation elongation speed and ribosomal profiling biases in mouse embryonic stem cells. PLoS Comput Biol. 2012;8 doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hussmann J.A., Patchett S., Johnson A., Sawyer S., Press W.H. Understanding biases in ribosome profiling experiments reveals signatures of translation dynamics in yeast. PLoS Genet. 2015;11 doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stadler M., Fire A. Wobble base-pairing slows in vivo translation elongation in metazoans. RNA. 2011;17:2063–2073. doi: 10.1261/rna.02890211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chevance F.F.V., Hughes K.T. Case for the genetic code as a triplet of triplets. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2017;114:4745–4750. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1614896114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chevance F.F.V., Le Guyon S., Hughes K.T. The effects of codon context on in vivo translation speed. PLoS Genet. 2014;10 doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pickett B.E., Sadat E.L., Zhang Y., Noronha J.M., Squires R.B., Hunt V. ViPR: an open bioinformatics database and analysis resource for virology research. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:D593–D598. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Larkin M.A., Blackshields G., Brown N.P., Chenna R., McGettigan P.A., McWilliam H. Clustal W and clustal X version 2.0. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:2947–2948. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Wit E., van Doremalen N., Falzarano D., Munster V.J. SARS and MERS: recent insights into emerging coronaviruses. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2016;14:523–534. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro.2016.81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Song Z., Xu Y., Bao L., Zhang L., Yu P., Qu Y. From SARS to MERS, thrusting coronaviruses into the spotlight. Viruses. 2019;11:E59. doi: 10.3390/v11010059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Herfst S., Böhringer M., Karo B., Lawrence P., Lewis N.S., Mina M.J. Drivers of airborne human-to-human pathogen transmission. Curr Opin Virol. 2017;22:22–29. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2016.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]