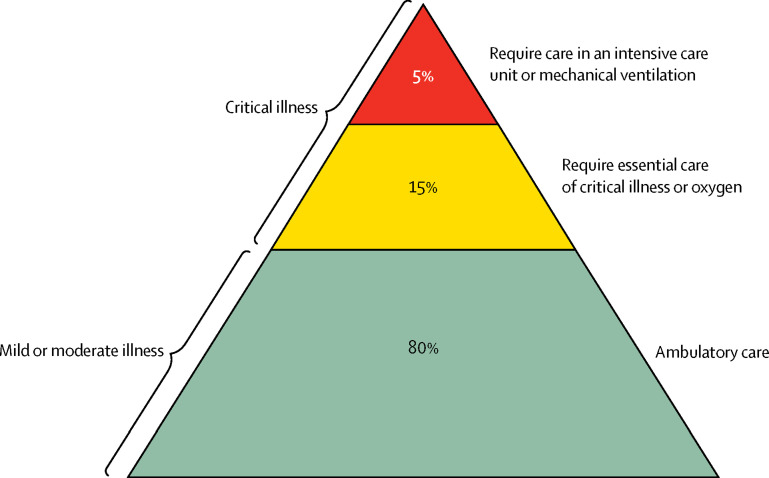

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic will have a large impact in low-resource settings (LRS). 20% of COVID-19 patients become critically ill with hypoxia or respiratory failure (figure ).1 Critical illness, describing any acute life-threatening condition, is receiving increased attention in global health because of its large disease burden and population impact.2 Before the COVID-19 pandemic, growing evidence suggested that the care of critical illness was overlooked in LRS—hospitals cannot, or do not, prioritise emergency and critical care.3 Most critically ill patients are cared for in emergency units and general wards and do not have access to advanced care in intensive care units (ICUs). Data from hospital wards in Malawi showed that 89% of hypoxic patients (oxygen saturation <90%) were not receiving oxygen, and 53% of unconscious patients (Glasgow Coma Scale <9) were being nursed supine without a protected airway (unpublished data).

Figure.

Severity profile of coronavirus disease 2019

Data source: Wu et al (2020).1

The COVID-19 pandemic will lead to a surge in the number of critically ill patients.4 Hospitals throughout the world will become overwhelmed, and care will be provided at a lower resource level than usual. Along with preventive measures and infection control, the clinical care of these patients will be a fundamental determinant of the pandemic's overall impact.

Unfortunately, the headline figures of ICU requirements for COVID-19 patients in resource-rich settings are masking the need for essential care. Attention is directed towards expensive, high-tech equipment that demands highly trained providers while neglecting low-cost essential care.

To avoid this neglect, we recommend a primary policy focus on basic, effective actions with potential population impact. A conceptual framework has recently been proposed that illustrates the need for hospital readiness and good quality clinical practice for the dual aspects of identification and care of critically ill patients (appendix).5 Hospitals should establish effective systems for triage and essential care in emergency units and wards, including patient separation and staff safety. User-friendly, concise protocols should be developed, disseminated, and implemented for good quality and feasible clinical care, with WHO's leadership and through national authorities. Simple physiological signs have been shown to identify critical illness, and single-parameter systems might be easier to use than compound scores. The central role of oxygen therapy should be emphasised, oxygen supplies and delivery systems secured, and guidelines for sustainable and appropriate use issued. Other essential care includes a head-up patient position, suction, and simple chest physiotherapy. When human resources are limited, such care can be implemented by less trained health workers or vital-signs assistants through a protocolised approach and task sharing.

Quality essential care of critical illness could have a large positive effect on mortality even without ICUs. It would ameliorate the fatalism and passivity that arises from an absence of high-resource treatment options. Moreover, provision of essential care could prevent progression to multi-organ failure, reducing the burden on limited ICU capacity. The ability of health services in LRS and throughout the world to provide good quality essential care of critical illness must be greatly and urgently increased.

Acknowledgments

TB reports personal fees for a consultancy in Global Critical Care from the Wellcome Trust, unrelated to this Correspondence. DFM reports chairing the UK National Institutes of Health Research (NIHR) and Medical Research Council funding committee for COVID-19 for therapeutics and vaccines. DFM also reports personal fees from consultancy about acute respiratory disease for GlaxoSmithKline, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Bayer, unrelated to this Correspondence; in addition, DFM's institution has received funds from grants from the UK NIHR, Wellcome Trust, Innovate UK, and others, he has a patent issued to his institution for a treatment for acute respiratory distress syndrome, and he is Director of Research for the Intensive Care Society and NIHR Efficacy and Mechanism Evaluation Programme Director. All other authors declare no competing interests.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Wu Z, McGoogan JM. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: Summary of a report of 72314 cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.2648. published online Feb 25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adhikari NK, Fowler RA, Bhagwanjee S, Rubenfeld GD. Critical care and the global burden of critical illness in adults. Lancet. 2010;376:1339–1346. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60446-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reynolds T, Sawe HR, Rubiano A, Sang Do S, Wallis L, Mock C. World Bank; Washington, DC: 2018. Strengthening health systems to provide emergency care: DCP3 disease control priorities. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hopman J, Allegranzi B, Mehtar S. Managing COVID-19 in low- and middle-income countries. JAMA. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.4169. published online March 17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schell CO, Gerdin Wärnberg M, Hvarfner A. The global need for essential emergency and critical care. Crit Care. 2018;22:284. doi: 10.1186/s13054-018-2219-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.