Abstract

An outbreak of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) in Wuhan, China caused by SARS-CoV-2 has led to a serious epidemic in China and other countries, resulting in worldwide concern. With active efforts of prevention and control, more and more patients are being discharged. However, how to manage these patients normatively is still challenging. This paper reports an asymptomatic discharged patient with COVID-19 who retested positive for SARS-CoV-2, which arouses concern regarding the present discharge standards of COVID-19.

Keywords: COVID-19, Discharge standard, Turn positive

Since December 2019, an outbreak of COVID-19 in Wuhan, Hubei, China caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), has led to a serious epidemic in China and other countries, resulting in worldwide concern (Hui et al., 2020). Because of the seriousness of this outbreak, the World Health Organization declared it a public health emergency of international concern on January 30, 2020. As of February 21, 2020, 75,569 COVID-19 cases have been confirmed in China. Notably, 1200 confirmed cases have been reported in 26 other countries beyond China (World Health Organization, 2020).

China has taken unprecedented measures to contain the spread of the virus within the country since the outbreak. Although the number of cases outside China has remained relatively small, it is very challenging that some of these cases have no clear epidemiological link, and some asymptomatic carriers with SARS-CoV-2 might be a new potential source of infection. It is also very worrisome that South Korea now have the most confirmed cases outside China.

With huge efforts from medical professionals to treat patients, substantial public health prevention measures, and accelerated research, more and more patients are being discharged (World Health Organization, 2020). However, how to manage these patients normatively is still challenging. This paper reports an asymptomatic discharged patient with COVID-19 who retested positive for SARS-CoV-2, which led to re-evaluation of the present discharge standards of COVID-19.

A 54-year-old man had close contact with a person from Wuhan at a meeting on January 12, 2020. He felt fatigue and mild myalgia on January 17. On January 20, he began to have a fever of 37.5 °C, so went to the fever clinic of a tertiary hospital. A chest CT scan on January 20 showed multiple and scattered ground-glass opacities in the sub-pleural area of both lungs. He was immediately diagnosed with a suspected case of COVID-19 and isolated at an observation unit. On January 21, his throat swab sample tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 by real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction assay, and he was diagnosed as a confirmed COVID-19 case. Gradually, he had a mild to moderate dyspnea, and a fever of 38.3 °C on January 24. Another chest CT scan demonstrated an increasing area and number of ground-glass opacities in both lungs on January 24. He received supplemental oxygen at a rate of 5 liters/minute, and took antiviral drugs Arbidol, and a low-dose hormone since January 24. However, the symptoms did not improve so he was transferred to a COVID-19-designated hospital on January 27 and given antiviral treatment in an isolated ward . On February 2, his fever, cough and other symptoms had disappeared. A follow-up chest CT showed that the bilateral pulmonary lesions had resolved. His throat swab samples tested negative for SARS-CoV-2 on February 2 and February 4, respectively (Figures 1 and 2 ).

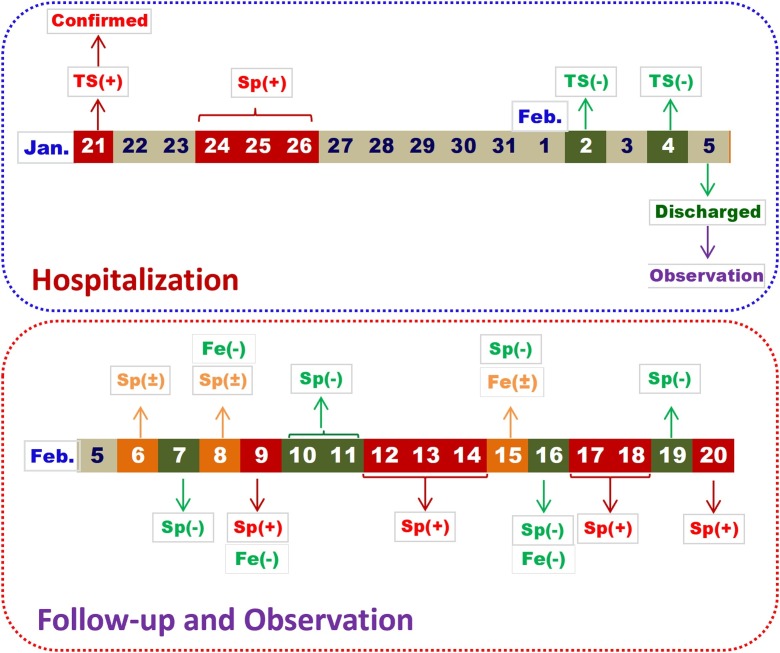

Figure 1.

Chronological changes of SARS-CoV-2 gene nucleic acid detection of a 54-year-old man with confirmed COVID-19.

The time point in the upper blue dotted frame refers to changes of SARS-CoV-2 gene nucleic acid detection during the hospitalization, and the time point in the lower red dotted frame means changes of SARS-CoV-2 gene nucleic acid testing after discharge and followed up at a designated medical unit.

TS, sample of throat swab.

Sp, sample of sputum.

Fe, sample of feces.

+ refers to positive.

- refers to negative.

± refers to weakly positive, which should be concerned and followed up.

Figure 2.

The same patient as Figure 1. Dynamic changes of SARS-CoV-2 viral load detection in sputum and throats swabs.

Ct value ≤37 refers to positive (+).

Ct value > 40 refers to negative (-).

37 < Ct value ≤40 refers weakly positive (±), which should be concerned and followed up.

According to the discharge standards as follows, a patient can be discharged and released from isolation: (1) the body temperature has returned to normal for >3 days; (2) respiratory symptoms have significantly improved; (3) lung inflammation has shown obvious signs of absorption; and (4) respiratory nucleic acid has been negative two consecutive times (at least 24 h apart). These guidelines were proposed by the National Health Commission of China (Jin et al., 2020, National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China, 2020).

However, the viral clearance pattern after SARS-CoV-2 infection remains unclear. For caution and safety, the committee of prevention and control of COVID-19 at the current hospital proposed local guidelines to manage discharged patients. All discharged COVID-19 patients are transferred to a designated medical unit for an extra 14 days’ quarantine and observation. As shown in Figure 1, the patient was transferred to a designated medical unit for isolation and monitoring after discharge on February 5. Unfortunately, nucleic acid detection for SARS-CoV-2 showed positive again. This caused a rethink of: the present discharge standards, whether persistent asymptomatic carriers of SARS-CoV-2 exists, and an accurate definition of when a patient can be considered to be cured.

Nucleic acid detection has certain possibilities of false negatives, which could mainly depend on the following situations: (1) the source of samples collected; (2) the method of samples collected; (3) antiviral drugs or hormone taken; (4) the sensitivity of the nucleic acid test kit (Xu et al., 2020, Laboratory testing, 2020).

Notably, the virus has been found in loose stools of a patient in the USA, suggesting potential transmission through the fecal-oral route (Holshue et al., 2020). Similarly, the current patient had a positive stool sample test once during the period under observation. Accordingly, the current hospital implemented these standards for discharge: both nasopharyngeal swab or sputum, and fecal virus nucleic acid detection have to be negative for more than two consecutive times (with an interval of >24 h).

This paper presents an asymptomatic and discharged patient with SARS-CoV-2 who retested positive, which aroused concern about the discharge standard of COVID-19. If any discharged individuals were contagious and released from quarantine, they might be a potential and mobile source of infection (Clinical management of severe acute respiratory infection when novel coronavirus, 2020).

Contributors

JFZ and TC designed the study, KY collected the data, HHY and JL analyzed the data, JFZ and JJZ wrote this article.

Conflict of interest

None.

Funding source

This study was supported by Key Research Foundation of Hwa Mei Hospital, University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, China (Grant No. 2020HMZD19; No. 2020HMZD20).

Ethical Approval

This study was approved by Ethics Committee of Hwa Mei Hospital.

References

- Clinical management of severe acute respiratory infection when novel coronavirus . 2020. (2019-nCoV) infection is suspected Interim guidance. 28 January.https://www.who.int/publications-detail/clinical-management-of-severe-acute-respiratory-infection-when-novel-coronavirus-(ncov)-infection-is-suspected [Google Scholar]

- Holshue M.L., DeBolt C., Lindquist S., Lofy K.H., Wiesman J., Bruce H. First case of 2019 novel coronavirus in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2020 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001191. published online Jan 31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hui D.S., IA E., Madani T.A., Ntoumi F., Kock R., Dar O. The continuing 2019-nCoV epidemic threat of novel coronaviruses to global health – The latest 2019 novel coronavirus outbreak in Wuhan, China. IJID. 2020;91:264–266. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin Y.H., Cai L., Cheng Z.S., Cheng H., Deng T., Fan Y.P. A rapid advice guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) infected pneumonia (standard version) Military Med Res. 2020;7(4):1–23. doi: 10.1186/s40779-020-0233-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laboratory testing . 2020. Laboratory testing for 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) in suspected human cases Interim guidance. 17 January.https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/technical-guidance/laboratory-guidance [Google Scholar]

- National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China . 2020. Diagnosis and treatment of novel coronavirus pneumonia (Trial version 5 revised) [EB/OL]. (2020-02-08) [2020-02-15] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . 2020. Novel coronavirus(2019-nCoV): situation report-32.https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200221-sitrep-32-covid-19.pdf?sfvrsn=4802d089_2 [Google Scholar]

- Xu K., Cai H., Shen Y., Ni Q., Chen Y., Hu S. Management of corona virus disease-19 (COVID-19): the Zhejiang experience. J Zhejiang Univ (Med Sci) 2020;49(1):1–12. doi: 10.3785/j.issn.1008-9292.2020.02.02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]