Abstract

Background: CD44+CD24-/low phenotypes are associated with poor outcome of triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC); however, the role of the CD44+CD24-/low phenotype in lymph node metastasis and survival has not been fully understood in TNBC. Methods: A total of 51 TNBC patients were included. CD44 and CD24 expression was determined using immunohistochemistry by which CD44 and CD24 were double-immunostained. Overall survival (OS) and disease-free survival (DFS) were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method. Results: The proportion of the CD44+CD24-/low phenotype was 33.3% in TNBC specimens without lymph node metastases and 69.0% in those with lymph node metastases. In addition, the CD44+CD24-/low phenotype correlated significantly with tumor size, histologic classification, TNM stage, and lymph node metastasis (P < 0.05). The CD44+CD24-/low phenotype was detected in 69.0% of TNBC patients with lymph node metastases, and 51.7% of TNBC patients without lymph node metastases. In TNBC patients without lymph node metastases, the median DFS and OS were 18.2 and 28 months in cases with a CD44+CD24-/low phenotype and 26.5 and 42.5 months in those without a CD44+CD24-/low phenotype (P < 0.05), and in TNBC patients with lymph node metastases, the median DFS and OS were 17.2 and 25.7 months in cases with a CD44+CD24-/low phenotype and 24.5 and 39.3 months in those without a CD44+CD24-/low phenotype, respectively (P < 0.05). Conclusions: CD44 and CD24 are independent prognostic markers for patients with TNBC. The CD44+CD24-/low phenotype correlates with more aggressive clinicopathologic features and is strongly associated with poor prognosis in patients with TNBC.

Keywords: Triple-negative breast cancer, CD44, CD24, cancer stem cells, survival, lymph node metastasis

Introduction

Breast cancer is the second most common cancer and the fifth leading cause of cancer death worldwide, and in females, breast cancer is the most commonly diagnosed cancer and causes the greatest number of cancer-related deaths [1]. In 2018, 2.09 million cases were estimated to have newly diagnosed breast cancer, and 627,000 women died from breast cancer across the world [2]. Triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) is a heterogeneous subtype of breast cancer that is defined as absence of oestrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR) and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) expression, which represents 15% to 20% of all breast cancer [3]. TNBC, which is characterized by high invasion, rapid progression and low survival, is accepted to have a poorer outcome relative to other breast cancer subtypes [4]. More importantly, there is currently no effective treatment for TNBC [5-7]. Development of novel treatment options to improve the prognosis and survival is therefore given a high priority.

Cancer stem cells (CSCs) are a small population of tumor cells that exhibit the capability to sustain self-renewal, proliferation and differentiation, which have been proven to contribute to tumorigenesis, metastasis and resistance to chemotherapy [8-11]. Breast cancer stem cells (BCSCs) are a small population of cells in breast cancer, identified based on the phenotype of CD44+CD24-/low expression [12]. This phenotype is strongly linked to poor prognosis and other prognostic factors, such as hormone receptor status, tumor histologic grade, and proliferation index [13,14]. In addition, the subpopulation of CD44+CD24-/low cells, which has shown a tumor-initiating capability in human breast, is associated with relapse and metastasis of breast cancer [15,16]. Previous studies have demonstrated that CD44+CD24-/low phenotypes are more abundant in TNBC than in other breast cancer subtypes, and are associated with poor outcomes [17-19]; however, the role of the CD44+CD24-/low phenotype in lymph node metastasis and survival has not been fully understood in TNBC. The present study was therefore designed to investigate the association of the CD44 and CD24 phenotype with the lymph node metastasis and survival of TNBC.

Materials and methods

Ethical statement

This study was approved by the Ethics Review Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Bengbu Medical College. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants following a detailed description of the purpose of the study. All experiments described in this study were performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, international and national guidelines, laws and regulations.

Specimens

A total of 346 female patients with breast cancer that underwent breast surgery in the First Affiliated Hospital of Bengbu Medical College (Bengbu, China) during the period between May 2010 and March 2014 were recruited, and all diagnoses were confirmed by intraoperative or postoperative pathologic examinations. Of these patients, there were 51 TNBC cases, as revealed by the negative receptor status in breast cancer specimens using immunohistochemistry (IHC). Patients without TNBC or with distant organ metastasis or at stage IV based on prior surgery were excluded from this study. All demographic and clinical features were captured from the medical and inpatient records.

IHC

The expression of ER, PR, HER2, Ki-67, P53, CD24, and CD44 was determined in breast cancer specimens using IHC. Briefly, formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded sections were deparaffinized in xylene, rehydrated in graded alcohol solutions and incubated in 0.3% hydrogen peroxide for 15 min to block the endogenous peroxidase activity. Following antigen retrieval in citrate buffer (10 mM; pH 6.0) at 98°C for 15 min, sections were blocked with 10% goat serum in PBS (pH 6.0) for 10 min, and stained on a DAKO Autostainer Plus (DAKO Corporation; Carpinteria, CA, USA) using the DAKO LSAB + Peroxidase detection kit (DAKO Corporation; Carpinteria, CA, USA). Then, sections were incubated with the primary rabbit anti-CD44 (1:100 dilution; ab51037; Abcam; Cambridge, MA, USA) and mouse anti-CD24 monoclonal antibodies (1:500 dilution; ab31622; Abcam; Cambridge, MA, USA) at 4°C overnight. Finally, antibody staining was visualized with 3,3’-diaminobenzidine (DAB) and counterstained with haematoxylin.

Double-immunostaining

Double-immunostaining of CD44 and CD24 was performed using the EnVision G/2 Doublestain System, Rabbit/Mouse DAB+/Permanent Red (DAKO Corporation; Carpinteria, CA, USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, deparaffinization, rehydration and antigen retrieval were done as described above. The, sections were incubated with the mixture of the primary rabbit anti-CD44 (1:100 dilution) and mouse anti-CD24 monoclonal antibodies (1:500 dilution) at 37°C for 2 h. After rinsing in PBS, sections were incubated in a mixture of biotin-conjugated anti-rabbit and anti-mouse secondary antibody at room temperature for 20 min. CD44 staining was visualized with DAB, and CD24 staining was visualized with Permanent Red. The double-immunostaining accuracy was evaluated by comparing with single immunostaining for CD44 and CD24. The number of CD44+CD24-/low cancer cells was counted semiquantitatively and scored in 5% increments.

Survival analysis

Disease free survival (DFS) was defined as the duration from the date of diagnosis to the emergence of a local relapse or distant metastasis. Overall survival (OS) was defined as the duration from the date of diagnosis to the death of the patient. Survival analysis was estimated with the Kaplan-Meier method by GraphPad Prism 7 (GraphPad Software, Inc.; La Jolla, CA, USA).

Statistics

All data were managed using Microsoft Excel 2010 (Microsoft; Redmond, WA, USA), and all statistical analyses were done using the statistical software SPSS version 21 (SPSS, Inc.; Chicago, IL, USA). Differences of proportions were tested for statistical significance by chi-square test, and a P value of < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Demographic and clinical characteristics

The 51 TNBC patients had a median age of 50 years (range, 21 to 78 years) at enrollment. All cases were followed up and 5 cases were lost to follow-up. To date, there are 6 survival cases and 40 deaths. Positive CD44 and CD24 expression was detected in 39.2% (20/51) and 9.8% (5/51) of the TNBC specimens without lymph node metastases, and in 69.0% (30/29) and 6.9% (2/29) of TNBC specimens with lymph node metastases. The proportion of the CD44+CD24-/low phenotype was 33.3% (17/51) in TNBC specimens without lymph node metastases and 69.0% (20/29) in those with lymph node metastases. In addition, the CD44+CD24-/low phenotype correlated with tumor size, histology classification, TNM stage, and lymph node metastasis (P < 0.05) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Associations of the CD44/CD24 phenotype with the clinicopathologic characteristics in triple-negative breast cancer

| Characteristics | N (%) of CD44+ | N (%) of CD24+ | N (%) of CD44/CD24 phenotype | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

| Positive | Negative | Positive | Negative | N (%) of CD44+CD24+ | N (%) of CD44+CD24-/low | N (%) of CD44-D24+ | N (%) of CD44-CD24- | ||

| Age (years) | < 35 (n = 2) | 2 (3.9%) | 0 (0.00%) | 1 (2.0%) | 1 (2.0%) | 1 (2.0%) | 1 (2.0%) | 0 (0.00%) | 0 (0.00%) |

| ≥ 35 (n = 49) | 18 (35.3%) | 31 (60.8%) | 4 (7.8%) | 45 (88.2%) | 2 (3.9%) | 16 (31.4%) | 2 (3.9%) | 29 (56.9%) | |

| Menopausal status | Premenopausal (n = 28) | 9 (17.6%) | 19 (37.3%) | 3 (10.7%) | 25 (49.0%) | 2 (3.9%) | 7 (13.7%) | 1 (2.0%) | 18 (35.3%) |

| Postmenopausal (n = 23) | 11 (21.6%) | 12 (23.5%) | 2 (3.9%) | 21 (41.2%) | 1 (2.0%) | 10 (19.6%) | 1 (2.0%) | 11 (21.6%) | |

| Tumor size (cm) | ≤ 2 (n = 11) | 0 (0.00%) | 11 (21.6%) | 0 (0.00%) | 11 (21.6%) | 0 (0.00%) | 0 (0.00%) | 0 (0.00%) | 11 (21.6%) |

| > 2, ≤ 5 (n = 32) | 13 (25.5%) | 19 (37.3%) | 4 (7.8%) | 28 (54.9%) | 2 (3.9%) | 10 (19.6%) | 2 (3.9%) | 18 (35.3%) | |

| > 5 (n = 8) | 7 (13.7%) | 1 (2.0%)a | 1 (2.0%) | 7 (13.7%) | 1 (2.0%) | 7 (13.7%) | 0 (0.00%) | 0 (0.00%)e | |

| Histologic grade | I and II (n = 28) | 6 (11.8%) | 22 (43.1%) | 1 (2.0%) | 27 (52.9%) | 0 (0.00%) | 6 (11.8%) | 1 (2.0%) | 21 (41.2%) |

| III (n = 23) | 14 (27.5%) | 9 (17.6%)b | 4 (7.8%) | 19 (37.3%) | 3 (5.9%) | 11 (21.6%) | 1 (2.0%) | 8 (15.7%)f | |

| pTNM stage | I and II (n = 30) | 6 (11.8%) | 24 (47.1%) | 1 (2.0%) | 29 (56.9%) | 1 (2.0%) | 5 (9.8%) | 2 (3.9%) | 22 (43.1%) |

| III (n = 21) | 14 (27.5%) | 7 (13.7%)c | 4 (7.8%) | 17 (33.3%) | 2 (3.9%) | 12 (23.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | 7 (13.7%)g | |

| Ki-67 (%) | ≤ 20 (n = 17) | 5 (9.8%) | 12 (23.5%) | 2 (3.9%) | 15 (29.4%) | 1 (2.0%) | 4 (7.8%) | 1 (2.0%) | 11 (21.6%) |

| > 20 (n = 34) | 15 (29.4%) | 19 (37.3%) | 3 (5.9%) | 31 (60.8%) | 2 (3.9%) | 13 (25.5%) | 1 (2.0%) | 18 (35.3%) | |

| P53 | Negative (n = 18) | 4 (7.8%) | 14 (27.5%) | 0 (0.00%) | 18 (35.3%) | 0 (0.00%) | 4 (7.8%) | 0 (0.00%) | 14 (27.5%) |

| Positive (n = 33) | 16 (31.4%) | 17 (33.3%) | 5 (9.8%) | 28 (54.9%) | 3 (5.9%) | 13 (25.5%) | 2 (3.9%) | 15 (29.4%) | |

| Lymph node metastasis | Negative (n = 22) | 3 (5.9%) | 19 (37.3%) | 1 (2.0%) | 21 (41.2%) | 0 (0.00%) | 0 (0.00%) | 2 (2.0%) | 20 (39.2%) |

| Positive (n = 29) | 17 (33.3%) | 12 (23.5%)d | 4 (7.8%) | 25 (49.0%) | 0 (0.00%) | 20 (39.2%) | 0 (0.0%) | 9 (17.6%)h | |

P = 0.000;

P = 0.004;

P = 0.001;

P = 0.001;

P = 0.000;

P = 0.007;

P = 0.003;

P = 0.003.

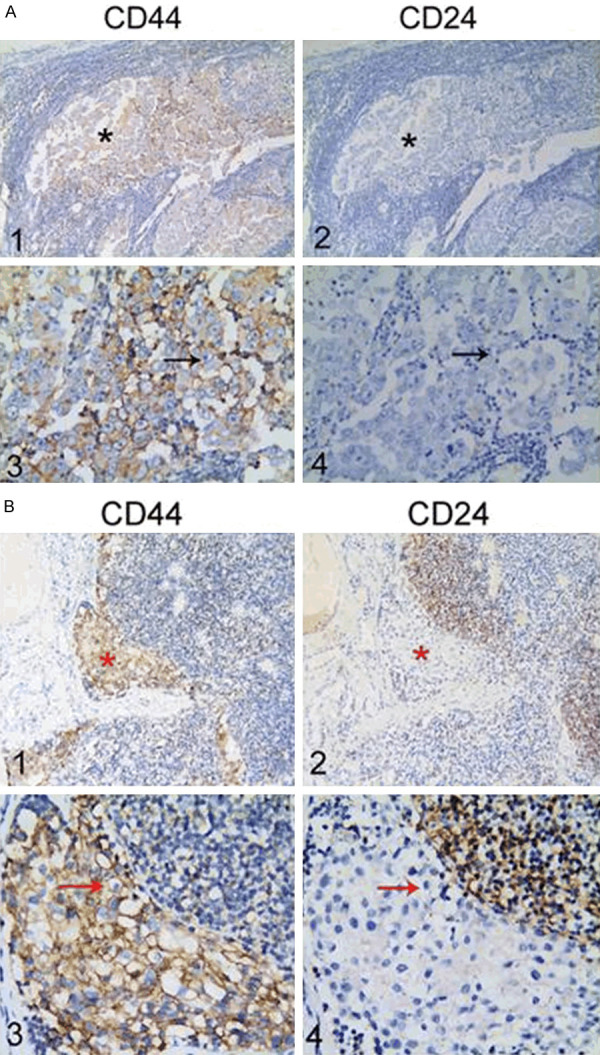

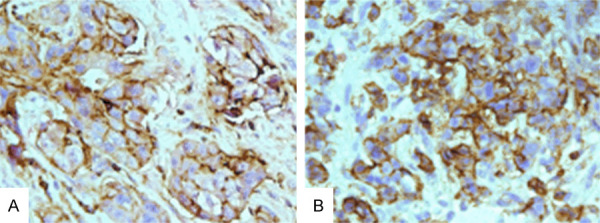

Expression of CD44/CD24 immunophenotypes in TNBC

Immunostaining of CD44 and CD24 was performed in TNBC specimens with and without lymph node metastases (Figure 1), and CSCs were identified by the phenotype of the CD44+CD24-/low expression presenting with positive CD44 expression and negative or low CD24 expression, as revealed by the immunostaining (Figure 2). The CD44+CD24-/low phenotype was detected in 69.0% (20/29) of the TNBC patients with lymph node metastases, and 51.7% (15/29) of TNBC patients without lymph node metastases, and the concordance rate of the CD44+CD24-/low phenotype was 51.7% between TNBC patients with and without lymph node metastases (Table 2).

Figure 1.

Immunostaining of CD44 and CD24 in triple-negative breast cancer specimens with and without lymph node metastases. A1 and A3. Positive CD44 staining in triple-negative breast cancer specimens without lymph node metastases; A2 and A4. Negative CD24 staining in triple-negative breast cancer specimens without lymph node metastases; B1 and B3. Positive CD44 staining in triple-negative breast cancer specimens with lymph node metastases; B2 and B4. Negative CD24 staining in triple-negative breast cancer specimens with lymph node metastases. * indicates tumor foci in triple-negative breast cancer specimens with and without lymph node metastases, and the arrows show positive CD44 expression and negative CD24 expression. A1, A2, B1 and B2. Magnification of × 10; A3, A4, B3 and B4. Magnification of × 40.

Figure 2.

Double immunostaining of CD44 and CD24 in triple-negative breast cancer specimens with and without lymph node metastases (× 40). Circumferential membranous staining (permanent brown staining) shows CD44 expression, and low (A) or negative CD24 staining (B) is found in the membrane and cytoplasm.

Table 2.

Positive rate and concordance rate of CD44/CD24 phenotypes in TNBC specimens with and without lymph node metastases

| Phenotype | Positive rate (%) | Concordance rate between patients with and without lymph node metastasis (%)* | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| No. lymph node metastasis | Lymph node metastasis | ||

| CD44+CD24-/low | 51.7 (15/29) | 69 (20/29) | 51.7 (15/29) |

| CD44-CD24- | 48.3 (14/29) | 24.1 (7/29) | 24.1 (7/29) |

| CD44-CD24+ | 0 (0/29) | 6.9 (2/29) | 0 (0/29) |

| CD44+CD24+ | 0 (0/29) | 0 (0/29) | 0 (0/29) |

Concordance rate is calculated as a combination of both positive and negative cases in primary and lymph node metastasis, divided by total number of cases.

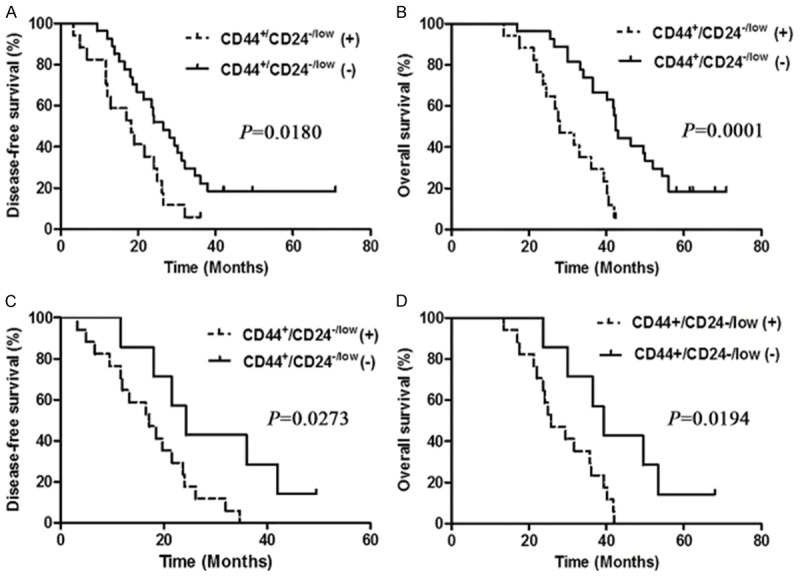

Survival analysis in TNBC patients with the CD44+CD24-/low phenotype

During the follow-up period, 5 TNBC patients were lost to follow-up, including 3 cases with lymph node metastasis, and a total of 46 cases were included for evaluating DFS and OS. In TNBC patients without lymph node metastases, the median DFS and OS were 18.2 and 28 months in cases with a CD44+CD24-/low phenotype and 26.5 and 42.5 months in those without a CD44+CD24-/low phenotype (P = 0.018 for DFS and 0.0001 for OS), and in TNBC patients with lymph node metastases, the median DFS and OS were 17.2 and 25.7 months in cases with a CD44+CD24-/low phenotype and 24.5 and 39.3 months in those without a CD44+CD24-/low phenotype (P = 0.0273 for DFS and 0.0194 for OS), respectively (Figure 3). Therefore, there was a worse prognosis in TNBC patients with a CD44+CD24-/low phenotype relative to those without a CD44+CD24-/low phenotype, regardless of lymph node metastasis.

Figure 3.

Kaplan-Meier curves of disease-free survival and overall survival in triple-negative breast cancer patients. A. Comparison of disease-free survival between patients without lymph node metastases positive and negative for the CD44+CD24-/low phenotype; B. Comparison of overall survival between patients without lymph node metastases positive and negative for the CD44+CD24-/low phenotype; C. Comparison of disease-free survival between patients with lymph node metastases positive and negative for the CD44+CD24-/low phenotype; D. Comparison of overall survival between patients with lymph node metastases positive and negative for the CD44+CD24-/low phenotype.

Discussion

TNBC is a unique subtype of breast cancer with a poor prognosis and is characterized by high malignancy, invasion, recurrence and metastasis [3]. Relapse and metastasis are frequently the important reasons for unfavorable prognoses [3-5]. Therefore, it is particularly important to identify sensitive diagnostic and prognostic markers for TNBC patients at the early stage.

CD24 is a cell adhesion molecule that has been implicated in metastatic tumor progression of various solid tumors [20], and CD24 is overexpressed in multiple human cancers [21-24]. In addition, CD24 expression has been identified as a prognostic factor in diverse human malignant tumors [25-30]. In this study, we found that low or negative expression of CD24 was significantly correlated with poor prognosis in patients with TNBC. CD44 is a transmembrane glycoprotein receptor [31], and its expression is upregulated in aggressive cancers and is closely associated with cancer metastasis and chemotherapy resistance [32-34]. CD44 is involved in tumor growth, differentiation, adhesion, and survival [35], and CD44 expression has been identified as a predictor of OS in human cancers [36-38]. In this study, CD44 was overexpressed in patients with TNBC, notably in those with lymph node metastases, and the upregulation of CD44 expression was significantly related to shorter DFS and OS in TNBC patients, in agreement with previous reports [36-38]. Since CD24 or CD44 expression, however, was reported not to predict DFS or OS in human cancers [39], further large prospective clinical trials are required to investigate the clinical significance of CD24 and CD44 expression as independent prognostic factors in TNBC.

CSCs, the seed cells of tumor metastasis, have important roles in tumorigenesis, recurrence, metastasis and drug resistance in cancers [10]. As CSC surface markers [40], CD24/CD44 expression is classified into four subtypes based on molecular characteristics. However, the role of these phenotypes has not been fully understood in TNBC until now. Previous studies have demonstrated that CD44+CD24-/low phenotype is most common in TNBC [41-43]; however, the correlation between the CD44+CD24-/low phenotype and prognosis in TNBC remains in dispute. The CD44+CD24-/low, CD44-CD24-, and CD44-CD24+ phenotypes are most likely to be associated with a worse prognosis in TNBC patients [44-46]. In this study, we examined, for the first time, the prognosis of TNBC patients with and without lymph node metastases who had diverse CD44/CD24 expression, and we found that the CD44+CD24-/low phenotype was the most common subtype of TNBC compared with other phenotypes. In addition, significantly shorter OS and DFS were seen in TNBC patients with the CD44+CD24-/low phenotype relative to those without the CD44+CD24-/low phenotypes. Our data indicate that the CD44+CD24-/low phenotype is strongly associated with a poor prognosis in patients with TNBC, which was consistent with the finding that a CD44+CD24-/low profile indicates a poor prognosis in breast cancer [17-19,47]. However, the CD44+CD24-/low phenotype was also reported not to be associated with clinical outcome and survival in breast cancer [16]. Further studies to examine the association between the CD44+CD24-/low profile and prognosis in TNBC are warranted.

The CD44+CD24-/low phenotype has been linked to the recurrence and metastasis of breast cancer [15,16], and a high proportion of CD44+CD24-/low cells are detected in metastatic and recurrent lesions of breast cancer [17]. In addition, the frequency of CSC markers was found not to differ between primary breast cancer and metastatic lesions [48]. Our data showed a 51.7% (15/29) frequency of lymph node metastasis in TNBC patients with the CD44+CD24-/low phenotype, and a 69.0% (20/29) positive rate of CD44+CD24-/low expression in TNBC patients with lymph node metastases, indicating that the frequency of the CD44+CD24-/low phenotype is associated with lymph node metastasis in TNBC. Previous studies have shown that the CD44+CD24-/low phenotype is significantly associated with the ER/PR status, tumor size and tumor grade [49]. In this study, we found that the CD44+CD24-/low phenotype was not associated with age, menopausal status, Ki-67 or P53 expression, but correlated with tumor size, histologic grade, TNM stage, and lymph node metastasis in TNBC, which was in agreement with previous reports found in breast cancer [47,49]. These data demonstrate that the CD44+CD24-/low phenotype correlates with more aggressive clinicopathological features of TNBC.

In summary, the results of the present study demonstrate that CD44 and CD24 are independent prognostic markers for patients with TNBC, and the CD44+CD24-/low phenotype correlates with more aggressive clinicopathologic features in TNBC. In addition, the CD44+CD24-/low phenotype is strongly associated with a poor prognosis in patients with TNBC. Our findings may provide new insights into the prognosis of patients with TNBC.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by grants from the Major Projects of the Natural Science Research in Anhui Provincial Colleges and Universities (grant no. KJ2018A0245), the Nature Science Key Program of Bengbu Medical College (grant no. BYKY1415ZD) and the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (grant no. BK20181365).

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.GBD 2017 Causes of Death Collaborators. Global, regional, and national age-sex-specific mortality for 282 causes of death in 195 countries and territories, 1980-2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet. 2018;392:1736–1788. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32203-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:394–424. doi: 10.3322/caac.21492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ismail-Khan R, Bui MM. A review of triple-negative breast cancer. Cancer Control. 2010;17:173–176. doi: 10.1177/107327481001700305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Griffiths CL, Olin JL. Triple negative breast cancer: a brief review of its characteristics and treatment options. J Pharm Pract. 2012;25:319–323. doi: 10.1177/0897190012442062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hurvitz S, Mead M. Triple-negative breast cancer: advancements in characterization and treatment approach. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2016;28:59–69. doi: 10.1097/GCO.0000000000000239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bayraktar S, Glück S. Molecularly targeted therapies for metastatic triple-negative breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2013;138:21–35. doi: 10.1007/s10549-013-2421-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Greenberg S, Rugo HS. Challenging clinical scenarios: treatment of patients with triple-negative or basal-like metastatic breast cancer. Clin Breast Cancer. 2010;10(Suppl 2):S20–S29. doi: 10.3816/CBC.2010.s.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reya T, Morrison SJ, Clarke MF, Weissman IL. Stem cells, cancer, and cancer stem cells. Nature. 2001;414:105–111. doi: 10.1038/35102167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barkeer S, Chugh S, Batra SK, Ponnusamy MP. Glycosylation of cancer stem cells: function in stemness, tumorigenesis, and metastasis. Neoplasia. 2018;20:813–825. doi: 10.1016/j.neo.2018.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Batlle E, Clevers H. Cancer stem cells revisited. Nat Med. 2017;23:1124–1134. doi: 10.1038/nm.4409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abbaszadegan MR, Bagheri V, Razavi MS, Momtazi AA, Sahebkar A, Gholamin M. Isolation, identification, and characterization of cancer stem cells: a review. J Cell Physiol. 2017;232:2008–2018. doi: 10.1002/jcp.25759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Filipova A, Seifrtova M, Mokry J, Dvorak J, Rezacova M, Filip S, Diaz-Garcia D. Breast cancer and cancer stem cells: a mini-review. Tumori. 2014;100:363–369. doi: 10.1700/1636.17886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wei W, Hu H, Tan H, Chow LW, Yip AY, Loo WT. Relationship of CD44+CD24-/low breast cancer stem cells and axillary lymph node metastasis. J Transl Med. 2012;10(Suppl 1):S6. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-10-S1-S6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chekhun VF, Lukianova NY, Chekhun SV, Bezdieniezhnykh NO, Zadvorniy TV, Borikun TV, Polishchuk LZ, Klyusov OМ. Association of CD44+CD24-/low with markers of aggressiveness and plasticity of cell lines and tumors of patients with breast cancer. Exp Oncol. 2017;39:203–211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Honeth G, Bendahl PO, Ringnér M, Saal LH, Gruvberger-Saal SK, Lövgren K, Grabau D, Fernö M, Borg A, Hegardt C. The CD44+CD24- phenotype is enriched in basal-like breast tumors. Breast Cancer Res. 2008;10:R53. doi: 10.1186/bcr2108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abraham BK, Peter F, Monika MC, Petra H, Maria A, Hiltrud B. Prevalence of CD44+CD24-/low cells in breast cancer may not be associated with clinical outcome but may favor distant metastasis. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:1154–1159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Idowu MO, Kmieciak M, Dumur C, Burton RS, Grimes MM, Powers CN, Manjili MH. CD44+CD24-/low cancer stem/progenitor cells are more abundant in triple-negative invasive breast carcinoma phenotype and are associated with poor outcome. Hum Pathol. 2012;43:364–373. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2011.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang H, Wang L, Song Y, Wang S, Huang X, Xuan Q, Kang X, Zhang Q. CD44+CD24- phenotype predicts a poor prognosis in triple-negative breast cancer. Oncol Lett. 2017;14:5890–5898. doi: 10.3892/ol.2017.6959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chang SJ, Ou-Yang F, Tu HP, Lin CH, Huang SH, Kostoro J, Hou MF, Chai CY, Kwan AL. Decreased expression of autophagy protein LC3 and stemness (CD44+CD24-/low) indicate poor prognosis in triple-negative breast cancer. Hum Pathol. 2016;48:48–55. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2015.09.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fang X, Zheng P, Tang J, Liu Y. CD24: from A to Z. Cell Mol Immunol. 2010;7:100–103. doi: 10.1038/cmi.2009.119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nagy B, Szendroi A, Romics I. Overexpression of CD24, c-myc and phospholipase 2A in prostate cancer tissue samples obtained by needle biopsy. Pathol Oncol Res. 2009;15:279–283. doi: 10.1007/s12253-008-9077-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee JH, Kim SH, Lee ES, Kim YS. CD24 overexpression in cancer development and progression: a meta-analysis. Oncol Rep. 2009;22:1149–1156. doi: 10.3892/or_00000548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shi Y, Gong HL, Zhou L, Tian J, Wang Y. CD24: a novel cancer biomarker in laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma. ORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec. 2012;74:78–85. doi: 10.1159/000335584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhu J, Zhang G, Lu H. CD24, COX-2, and p53 in epithelial ovarian cancer and its clinical significance. Front Biosci (Elite Ed) 2012;4:2645–51. doi: 10.2741/e580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yang XR, Xu Y, Yu B, Zhou J, Li JC, Qiu SJ, Shi YH, Wang XY, Dai Z, Shi GM, Wu B, Wu LM, Yang GH, Zhang BH, Qin WX, Fan J. CD24 is a novel predictor for poor prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma after surgery. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:5518–5527. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-0151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Deng J, Gao G, Wang L, Wang T, Yu J, Zhao Z. CD24 expression as a marker for predicting clinical outcome in human gliomas. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2012;2012:517172. doi: 10.1155/2012/517172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang JL, Guo CR, Su WY, Chen YX, Xu J, Fang JY. CD24 overexpression related to lymph node invasion and poor prognosis of colorectal cancer. Clin Lab. 2018;64:497–505. doi: 10.7754/Clin.Lab.2017.171012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sano A, Kato H, Sakurai S, Sakai M, Tanaka N, Inose T, Saito K, Sohda M, Nakajima M, Nakajima T, Kuwano H. CD24 expression is a novel prognostic factor in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16:506–514. doi: 10.1245/s10434-008-0252-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Agrawal S, Kuvshinoff BW, Khoury T, Yu J, Javle MM, LeVea C, Groth J, Coignet LJ, Gibbs JF. CD24 expression is an independent prognostic marker in cholangiocarcinoma. J Gastrointest Surg. 2007;11:445–451. doi: 10.1007/s11605-007-0091-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Su MC, Hsu C, Kao HL, Jeng YM. CD24 expression is a prognostic factor in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Cancer Lett. 2006;235:34–39. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2005.03.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lesley J, Hyman R. CD44 structure and function. Front Biosci. 1998;3:d616–d630. doi: 10.2741/a306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen Y, Song J, Jiang Y, Yu C, Ma Z. Predictive value of CD44 and CD24 for prognosis and chemotherapy response in invasive breast ductal carcinoma. Int J Clin Exp Path. 2015;8:11287–11295. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Paulis YW, Huijbers EJ, van der Schaft DW, Soetekouw PM, Pauwels P, Tjan-Heijnen VC, Griffioen AW. CD44 enhances tumor aggressiveness by promoting tumor cell plasticity. Oncotarget. 2015;6:19634–19646. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.3839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu Y, Wu T, Lu D, Zhen J, Zhang L. CD44 overexpression related to lymph node metastasis and poor prognosis of pancreatic cancer. Int J Biol Markers. 2018;33:308–313. doi: 10.1177/1724600817746951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Marhaba R, Zöller M. CD44 in cancer progression: adhesion, migration and growth regulation. J Mol Histol. 2004;35:211–231. doi: 10.1023/b:hijo.0000032354.94213.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Huh JW, Kim HR, Kim YJ, Lee JH, Park YS, Cho SH, Joo JK. Expression of standard CD44 in human colorectal carcinoma: association with prognosis. Pathol Int. 2009;59:241–246. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.2009.02357.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chai L, Liu H, Zhang Z, Wang F, Wang Q, Zhou S, Wang S. CD44 expression is predictive of poor prognosis in pharyngolaryngeal cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2014;232:9–19. doi: 10.1620/tjem.232.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Luo Z, Wu RR, Lv L, Li P, Zhang LY, Hao QL, Li W. Prognostic value of CD44 expression in non-small cell lung cancer: a systematic review. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2014;7:3632–3646. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Spelt L, Sasor A, Ansari D, Hilmersson KS, Andersson R. The prognostic role of cancer stem cell markers for long-term outcome after resection of colonic liver metastases. Anticancer Res. 2018;38:313–320. doi: 10.21873/anticanres.12224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jaggupilli A, Elkord E. Significance of CD44 and CD24 as cancer stem cell markers: an enduring ambiguity. Clin Dev Immunol. 2012;2012:708036. doi: 10.1155/2012/708036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jin J, Krishnamachary B, Mironchik Y, Kobayashi H, Bhujwalla ZM. Phototheranostics of CD44-positive cell populations in triple negative breast cancer. Sci Rep. 2016;6:27871. doi: 10.1038/srep27871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stratford AL, Reipas K, Maxwell C, Dunn SE. Targeting tumour-initiating cells to improve the cure rates for triple-negative breast cancer. Expert Rev Mol Med. 2010;12:e22. doi: 10.1017/S1462399410001535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Collina F, Bonito MD, Bergolis VL, De Laurentiis M, Vitagliano C, Cerrone M, Nuzzo F, Cantile M, Botti G. Prognostic value of cancer stem cells markers in triple-negative breast cancer. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:158682. doi: 10.1155/2015/158682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Idowu MO, Kmieciak M, Dumur C, Burton RS, Grimes MM, Powers CN, Manjili MH. CD44+CD24-/low cancer stem/progenitor cells are more abundant in triple-negative invasive breast carcinoma phenotype and are associated with poor outcome. Hum Pathol. 2012;43:364–373. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2011.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ahmed MA, Aleskandarany MA, Rakha EA, Moustafa RZ, Benhasouna A, Nolan C, Green AR, Ilyas M, Ellis IO. A CD44-/CD24+ phenotype is a poor prognostic marker in early invasive breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;133:979–995. doi: 10.1007/s10549-011-1865-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Giatromanolaki A, Sivridis E, Fiska A, Koukourakis MI. The CD44+CD24- phenotype relates to ‘triple-negative’ state and unfavorable prognosis in breast cancer patients. Med Oncol. 2011;28:745–752. doi: 10.1007/s12032-010-9530-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Camerlingo R, Ferraro GA, De Francesco F, Romano M, Nicoletti G, Di Bonito M, Rinaldo M, D’Andrea F, Pirozzi G. The role of CD44+/CD24-/low biomarker for screening, diagnosis and monitoring of breast cancer. Oncol Rep. 2014;31:1127–1132. doi: 10.3892/or.2013.2943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Guler G, Balci S, Costinean S, Ussakli CH, Irkkan C, Suren D, Sari E, Altundag K, Ozisik Y, Jones S, Bacher J, Shapiro CL, Huebner K. Stem cell-related markers in primary breast cancers and associated metastatic lesions. Mod Pathol. 2012;25:949–955. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2012.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Makki J, Myint O, Wynn AA, Samsudin AT, John DV. Expression distribution of cancer stem cells, epithelial to mesenchymal transition, and telomerase activity in breast cancer and their association with clinicopathologic characteristics. Clin Med Insights Pathol. 2015;8:1–16. doi: 10.4137/CPath.S19615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]