Dear Editor,

In this journal, Azzi et al. reported that saliva was a reliable tool to detect SARS-CoV-2.1 We prospectively compared the efficacy of PCR detection of SARS-CoV-2 between paired nasopharyngeal and saliva samples in 76 patients including ten coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) patients. The overall concordance rate of the virus detection between the two samples reached as high as 97.4% (Table 1 ); we confirmed that saliva is a noninvasive and reliable alternative to nasopharyngeal swabs and facilitate widespread PCR testing in the face of shortages of swabs and protective equipment without posing a risk to healthcare workers.

Table 1.

Concordance of PCR results in COVID-19 patients between nasopharyngeal and saliva samples

| Nasopharyngeal | Positive | Negative | Cohen's kappa analysis | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Saliva | Positive | 8 | 1 | κ=0.874 (95%CI, 0.701-1) |

| Negative | 1 | 66 | ||

Nasopharyngeal swab and saliva samples were simultaneously collected from patients suspicious of COVID-19 and those with the diagnosis of COVID-19. This study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Board and informed consent was obtained from all patients. To collect nasopharyngeal samples, the swab was passed through the nostril until reaching the posterior nasopharynx and removed while rotating. Saliva were self-collected by the patients and spit into a sterile PP Screw cup 50 (ASIAKIZAI Co., Tokyo, Japan). 200 µL Saliva was added to 600 µL PBS, mixed vigorously, then centrifuged at 20,000 X g for 5 minutes at 4°C, and 140 µl of the supernatant was used as a sample. Real-time reverse transcription–quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) was conducted according to the manual for the Detection of Pathogen 2019-nCoV Ver.2.9.1 (https://www.niid.go.jp/niid/images/lab-manual/2019-nCoV20200319.pdf). Total RNA was extracted by QIAamp Viral RNA Mini Kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany). RT-qPCR was performed by One-Step Real-Time RT-PCR Master Mixes (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, USA) and tepOnePlus Real Time PCR System (Thermo Fisher Scientific) with forward primer (5-AAATTTTGGGGACCAGGAAC-3), reverse primer (5-TGGCAGCTGTGTAGGTCAAC-3) and TaqMan probe (5’-FAM-ATGTCGCGCATTGGCATGGA-BHQ-3’). We used the paired t-test to compare data. All P-values were 2-sided. Agreement between the samples for the virus detection ability was assessed using Cohen's Kappa. Statistical analyses were performed with EZR (Jichi Medical University, Saitama, Japan).

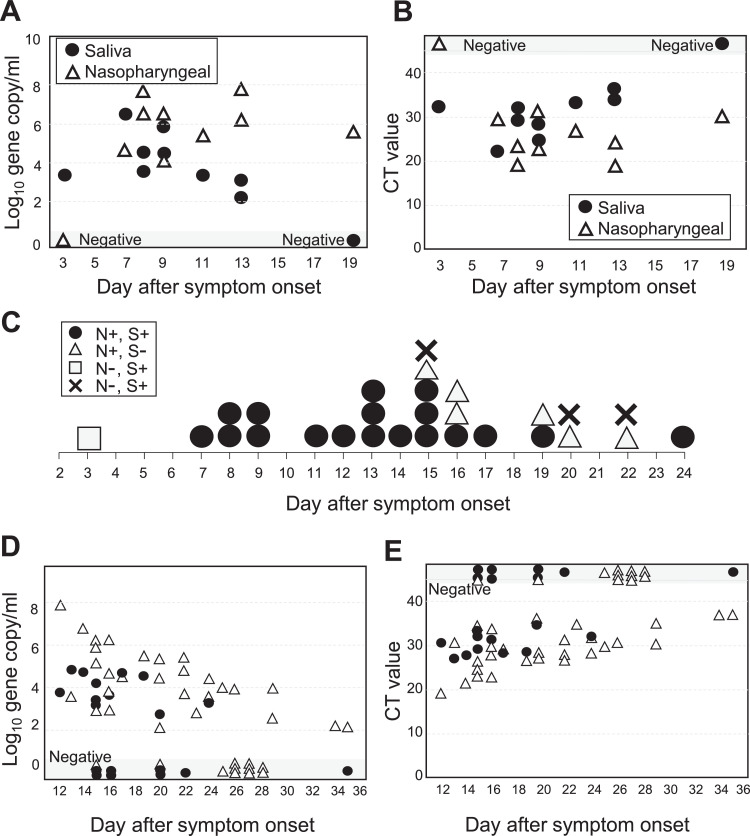

Seventy-six patients were enrolled in this study, including 10 patients with COVID-19 and sixty-six COVID-19 suspicious patients. Most of COVID-19 patients had mild to moderate disease, with no patient requiring ventilator. In COVID-19 patients, median age was 69 years-old (range, 30 to 97) and median day of sampling was 9 days (range, 3-19) after symptom onset. SARS-CoV-2 was detected in 8/10 patients in both nasopharyngeal and saliva samples, and in either sample only in 2/10 patients (Table 1). Of note, in one patient who showed saliva negativity, samples were taken 19 days after symptom onset. The overall concordance rate of the virus detection was 97.4% (95%CI, 90.8-99.7, Table 1). Concordance between was strong, as judged by Kohen’ s kappa coefficient. The viral loads were not significantly different between the two samples with mean 5.4 ± 2.4 and 4.1 ± 1.4 log10 gene copies/ml in nasopharyngeal and saliva samples, respectively (P=0.184). The cycle threshold (CT) values were not significantly different with mean 26.5 ± 8.1 and 30.6 ± 4.6 in nasopharyngeal and saliva samples, respectively (P=0.206). The viral loads were equivalent between the two samples at earlier time points but declined in saliva later (Fig. 1 A). The CT values were also not significantly different at earlier time points but tended to be higher in saliva later (Fig. 1B). Fig. 1C shows the results of PCR tests in all 28 samples taken from the 10 patients according time from symptom onset. All 12 saliva samples taken within 2 weeks after COVID-19 onset were positive in saliva. After 2 weeks, PCR became negative in some of the samples. Details of viral loads and CT values of all the samples taken at convalescent phase to determine the timing of discharge are shown in Fig. 1D, E. It seems that the saliva samples become PCR negative in patients at convalescent phase earlier than nasopharyngeal samples.

Fig. 1.

Detection of SAS-CoV-2 in nasopharyngeal and saliva samples. (A, B) Viral loads (A) and CT values (B) in ten COVID-19 patients according to the day after symptom onset. (C) Results of multiple PCR testing from the 10 patients according to the day after symptom onset. N, nasopharyngeal; S, saliva; +, positive; -, negative. (D, E) Viral loads (D) and CT values (E) in the patients at convalescent phase.

The diagnosis of COVID-19 is usually made by PCR testing of nasopharyngeal swab samples. However, swab sample collection requires specialized medical personnel with protective equipment and poses a risk of viral transmission. The angiotensin converting enzyme 2, the main receptor for SARS-CoV-2 entry to the human cell,2 is highly expressed on the mucous of oral cavity. Thus, it is reasonable to use saliva as a diagnostic sample, and recent studies have shown that SARS-CoV-2 is detected in saliva.1 , 3, 4, 5, 6 It has been shown that salivary viral load peaks at onset of symptoms and is highest during the first week and subsequently declines with time.3, 4, 5 , 7 , 8 Our results were consistent to these data; the virus was detected in all the saliva samples taken within 2 weeks after symptom onset and at convalescent phase the viral load decreased earlier in saliva compared to nasopharyngeal samples. Recent reports demonstrate that particle of the dead virus could persist in the nasopharynx and resulted in “false positivity”. Saliva might be a better tool to determine virus clearance in COVID-19 patients.

To our knowledge, a few studies compared viral load between nasopharyngeal and saliva samples. The viral loads were 5-times higher in saliva than in nasopharyngeal samples in one study,5 whereas they were lower in saliva in two studies.6 , 8 In one study, viral loads were equivalent in symptomatic patients, but lower in asymptomatic patients in saliva.9 Our results showed that the viral load was equivalent at earlier time points but lower in saliva than in nasopharyngeal samples at convalescent phase. Timing of sampling, severity of the disease, different methodologies of saliva collection and processing, different skill of swab sampling may be related to inconsistent results.

Although our study has several limitations due to the small number of samples, there have been few prospective studies to date comparing the two samples. Given the large benefits of saliva collection that does not require health worker specialists and protective equipment, our results together with recent studies support the use of saliva as a noninvasive alternative to nasopharyngeal swabs to greatly facilitate widespread PCR testing in the face of shortages of swabs and protective equipment without posing a risk to healthcare workers.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Azzi L., Carcano G., Gianfagna F., Grossi P., Gasperina D.D., Genoni A. Saliva is a reliable tool to detect SARS-CoV-2. J Infect. 2020 Apr 14 doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.04.005. PubMed PMID: 32298676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Letko M., Marzi A., Munster V. Functional assessment of cell entry and receptor usage for SARS-CoV-2 and other lineage B betacoronaviruses. Nat Microbiol. Apr. 2020;5(4):562–569. doi: 10.1038/s41564-020-0688-y. PubMed PMID: 32094589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.To K.K., Tsang O.T., Chik-Yan Yip C., Chan K.H., Wu T.C., Chan J.M.C. Consistent detection of 2019 novel coronavirus in saliva. Clin Infect Dis. 2020 Feb 12 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa149. PubMed PMID: 32047895. Pubmed Central PMCID: PMC7108139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.To K.K., Tsang O.T., Leung W.S., Tam A.R., Wu T.C., Lung D.C. Temporal profiles of viral load in posterior oropharyngeal saliva samples and serum antibody responses during infection by SARS-CoV-2: an observational cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. May. 2020;20(5):565–574. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30196-1. PubMed PMID: 32213337. Pubmed Central PMCID: PMC7158907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wyllie A.L., Fourmier J., Casanovas-Massana A., Campbell M., Tokuyama M., Vijayakumar P. Saliva is more sensitive for SARS-CoV-2 detectionin COVID-19 patients than nasopharyngeal swabs. medRxiv. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Williams E., Bond K., Zhang B., Putland M., Williamson D.A. Saliva as a non-invasive specimen for detection of SARS-CoV-2. J Clin Microbiol. 2020 Apr 21 doi: 10.1128/JCM.00776-20. PubMed PMID: 32317257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jamal M.A., Mohammad M., Coomes E. Sensitivity of nasopharyngeal swabs and saliva for the detection of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) medRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Becker D., Sandoval E., Amin A. Saliva is less sensitive than nasopharyngeal swabs for COVID-19 detection in the community setting. medRxiv. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Van Vinh Chau N., Thanh Lam V., Dung N.T., et al. The natural history and transmission potential of asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]