Until recently, the clinical course of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in children has been reported to be largely mild.1 , 2 Recently, it has become evident that a subset of children exposed to severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) can become critically ill with a condition now referred to as multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C), characterized by systemic hyperinflammation with fever and multisystem organ dysfunction.3 Gastrointestinal symptoms are increasingly recognized to be associated with the presentation of MIS-C, potentially confusing the diagnosis of MIS-C with other common, less toxic gastrointestinal infections and even inflammatory bowel disease. In the first published correspondence describing MIS-C in 8 patients from the United Kingdom, 100% presented with gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms.4 Similarly, 6 of 10 patients from an Italian cohort had GI issues.5 This is in contrast to adults, who most commonly present with respiratory symptoms and report GI symptoms in <10%–15% of cases.6 , 7 We examined whether similar presentations and prevalence extended to our comparatively larger US cohort of 44 patients (<21 years old) with MIS-C.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective chart review of the 44 patients who were hospitalized with a diagnosis of MIS-C at the Children’s Hospital at Columbia University Irving Medical Center between April 18 and May 22, 2020. The Children’s Hospital at Columbia University Irving Medical Center institutional review board approved this study with a waiver of informed consent.

Results

All patients had either documented SARS-CoV-2 exposure with clinically compatible symptoms, a positive SARS-CoV-2 nasopharyngeal swab by real-time reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction assay (Roche Cobas SARS-CoV-2 Test, Roche, Basel, Switzerland) (34%, N = 44) or positive antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 spike trimer or nucleocapsid protein using a New York State Department of Health–approved immunoassay (97%, n = 32) (Table 1 ).

Table 1.

Demographics, Gastrointestinal Presenting Symptoms and Associated Comorbidities, Treatment, and Outcome Status of Patients Admitted With MIS-C

| Characteristic | Values |

|---|---|

| Patients | N = 44 |

| Age | Median ± SD: 7.3 ± 4.98 y Range: 7 mo to 20 y |

| Sex, n (%) | Male: 20 (45) Female: 24 (55) |

| Ethnicity (or ancestry), n (%) | |

| White, non-Hispanic | 9 (20.5) |

| Black/African American | 9 (20.5) |

| Hispanic | 15 (34) |

| Not reported/declined to answer | 11 (25) |

| BMI, kg/m2 (n = 41 due to missing height for 3 children) | Median ± SD: 17.43 ± 6.4 Range: 13.9–41.8 |

| BMI, percentile for age/sex | Mean ± SD: 75.4 ± 31.0 Range: 3.7–99.7 |

| Overweight, BMI >85th percentile, n (%) | 16 (39.0) |

| Evaluated within 7 days before presentation, n (%) | 13 (29.5) |

| SARS-CoV-2 screening, n (%) | |

| SARS-CoV-2 nasopharyngeal PCR results (N = 44) | |

| Positive | 15 (34.1) |

| Indeterminate | 4 (9.1) |

| Negative | 25 (56.8) |

| SARS-CoV-2 antibody serology (n = 32) | |

| Positive | 31 (96.9) |

| Indeterminate | 1 (3.1) |

| Negative | 0 (0) |

| Suspicion with negative NP PCR | 5 (11.3) 1 indeterminate serology, 4 no serology testing |

| GI symptoms, n (%) | |

| Presenting with 1+ GI symptoms | 37 (84.1) |

| Abdominal pain | 33 (75.0) |

| Nausea | 8 (18.2) |

| Vomiting | 25 (56.8) |

| Diarrhea | 18 (40.1) |

| Hematemesis | 1 (2.3) |

| Hematochezia/melena | 2 (4.5) |

| Constipation | 5 (11.4) |

| Other system involvement, n (%) | |

| Fever | 44 (100) |

| Rash | 31 (70.5) |

| Conjunctivitis | 23 (52.3) |

| Strawberry tongue, cracked lips | 23 (52.3) |

| Cardiac (abnormalities on echocardiogram or dysrhythmia) | 22 (50) |

| Shock (requiring vasopressors) | 22 (50) |

| Neurologic (headache, vision changes, altered mental status, meningitis signs, cranial nerve palsy) | 13 (29.5) |

| Respiratory (hypoxia–supplemental oxygen requirement) | 11 (25) |

| Acute kidney injury | 7 (15.9) |

| Presenting value, median ± SD (range) | Minimum, median ± SD (range) | Maximum, median ± SD (range) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Laboratory evaluation (normal range) | |||

| White blood cells (4.2–9.4 × 103/μL) | 9.68 ± 6.9 (3.95–35.98) | 7.2 ± 4.66 (2.04–29.06) | 14.58 ± 11.84 (3.95–61.83) |

| Hemoglobin (10–13 g/dL) (normal value varies by age/sex) | 11.2 ± 1.8 (7.3–18.1) | 9.3 ± 1.9 (4.9–14.2) | |

| Platelet count (194–345 × 103/μL) | 200.0 ± 142.3 (69–892) | 158.5 ± 118.5 (13–600) | 355.0 ± 154.7 (189–892 |

| CRP (0–10 mg/L) | 146.5 ± 111.3 (2.96–300) | 171.1 ± 112.0 (2.96–300) | |

| Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (0-20 mm/h) | 59.0 ± 23.3 (21–130) | 69.0 ± 25.3 (24–130) | |

| Lactate dehydrogenase (140–280 U/L) (n = 39) |

328.0 ± 614.1 (178–4087) | ||

| Interleukin 6 (<5 pg/mL) (n = 31) | 219.2 ± 119.6 (3.1–315) | ||

| Albumin (3.9–5.2 g/dL) | 3.7 ± 0.6 (2–4.7) | 2.95 ± 0.73 (1.3–4.7) | |

| Low albumin ≤3.5, n (%) | 34 (77.3) | ||

| AST (10–37 U/L) | 31 ± 26.3 (15–133) | 33.5 ± 207.8 (15–7000) | |

| ALT (9–40 U/L) | 24.5 ± 34.4) (8–167) |

31 ± 673.3 (8–4557) | |

| Elevated AST and/or ALT, n (%) | 23 (52.3%) | ||

| Lipase (16–95 U/L) (n = 12) | 23 ± 86.0 (6–330) | 25.5 ± 161.2 (6–606) | |

| Amylase (34–137 U/L) | 104.5 ± 54.7 (18–179) | 104.5 ± 59.5 (18–179) | |

| Elevated lipase and/or amylase, n (%) | 1 (2.3) 1 with value >3× upper limit normal |

||

| GI PCR (n = 12) | 0 positive | ||

| Guaiac (n = 5) | 1 positive (20) | ||

| Gastrointestinal imaging (n = 15), abnormal finding/total performed (%) | |||

| Ultrasonography | 10/12 (83.3) | ||

| CT/MRI | 2/3 (66.7) | ||

| Treatment, n (%) | |||

| Steroids | 42 (95.5) | ||

| Intravenous immune globulin | 36 (81.8) | ||

| Anakinra | 8 (18.2) | ||

| Anticoagulation | 40 (90.1) | ||

| Outcomes, n (%) | |||

| Intubation | 1 (2.3) | ||

| Renal replacement therapy | 1 (2.3) | ||

| Mortality | 0 (0) | ||

| Discharged as of May 22, 2020 | 43 (97.7) | ||

BMI, body mass index; CI, confidence interval; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; NP, nasopharyngeal; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; SD, standard deviation.

Pertinent clinical and laboratory features are summarized in Table 1. GI symptoms were a presenting symptom in 84.1% of cases and were most often accompanied by fever (100%) and rash (70.5%). In contrast to adults, only 25% required supplemental oxygen, and 1 was intubated. Interestingly, 29.5% had presented within 7 days before admission at an emergency room or urgent care center for less severe symptoms such as fever and GI symptoms mimicking a viral gastroenteritis (eg, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea) but without other systemic symptoms. Of the 27% of patients who had a stool infectious polymerase chain reaction panel performed, 0% had an identified infection. Patients who initially presented with GI symptoms did not differ by sex or body mass index compared to those patients who presented without.

Overall, the majority of cases at admission had markedly elevated inflammatory markers: erythrocyte sedimentation rate (median, 59) mm/hr, c-reactive protein (CRP) (median, 146.5) mg/L, and mildly decreased albumin (median, 3.7) g/dL. Transaminases (alanine aminotransferase and/or aspartate aminotransferase) were elevated in 52.3%, and lipase was elevated >3 times the upper limit of normal in only 1 patient (Table 1).

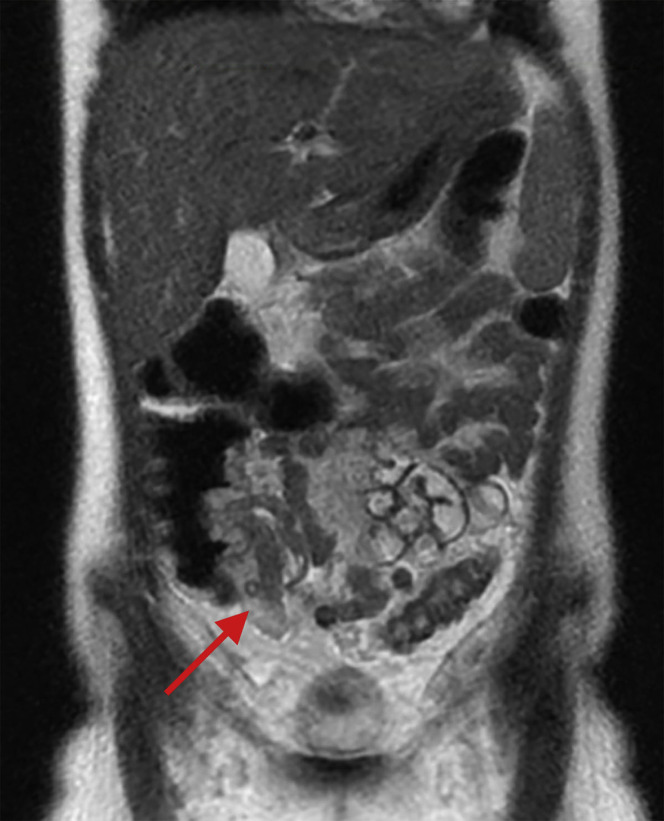

Abdominal imaging studies were performed in 34.1% of patients (n = 15) (Supplementary Table 1). Findings included mesenteric adenitis (n = 2), biliary sludge or acalculous cholecystitis (n = 6), and ascites (n = 6). Three (20.0%) had normal findings on abdominal imaging. In 3 patients, ultrasonography or magnetic resonance imaging showed bowel wall thickening (n = 3), which raised concern for inflammatory bowel disease, although the accompanying clinical manifestations were not typical of inflammatory bowel disease (Table 1). Of these patients, 1 had intense right lower quadrant abdominal pain, fever, and rash, with magnetic resonance imaging findings of severe concentric mural thickening, edema, and hyperenhancement of a short segment of terminal ileum with extensive mesenteric fat edema, as well as similar mural thickening in the rectosigmoid colon (presenting CRP, 184.7; erythrocyte sedimentation rate, 56; albumin, 3.7) (representative image in Supplementary Figure 1, area highlighted by red arrow). The 2 other patients had ultrasonography images showing nonspecific thickened bowel loops in the right lower quadrant with highly elevated CRP and mildly decreased to normal albumin levels.

Supplementary Figure 1.

Coronal magnetic resonance images. Short segment of severe concentric mural thickening, edema, and hyperenhancement of the terminal ileum.

Steroids were administered to 42 patients (95.5%) as methylprednisolone and/or hydrocortisone. Other therapies included intravenous immunoglobulins (81.8%), and anakinra (18.2%), with 90.1% receiving anticoagulation. At the time of this report, all except 1 were discharged, none required mechanical circulatory support, and 1 patient required renal replacement therapy. There were no fatalities.

Discussion

GI signs and symptoms appear prominently as presenting features of MIS-C.4 , 5 , 8 These data suggest that the vast majority of patients who develop this condition present with GI symptoms mimicking GI infection or even inflammatory bowel disease. MIS-C should thus be considered in patients with prominent GI symptoms and a history of recent SARS-CoV-2 exposure or infection. Although not uniformly, MIS-C can differ from these other conditions in both its clinical comorbidities and extremely high inflammatory markers. Among follow-up for other potential sequelae of organ dysfunction, long-term follow-up for the GI manifestations in some of these patients may warrant surveillance for IBD.

CRediT Authorship Contributions

Jonathan Miller, MD (Data curation: Supporting; Formal analysis: Equal; Investigation: Equal; Writing – review & editing: Equal); Amanda Cantor, MD (Data curation: Supporting; Investigation: Equal; Writing – review & editing: Equal); Philip Zachariah, MD, MS (Data curation: Supporting; Investigation: Supporting; Writing – review & editing: Equal); Danielle Ahn, MD (Data curation: Supporting; Investigation: Supporting; Writing – review & editing: Equal); Mercedes Martinez, MD (Conceptualization: Supporting; Data curation: Supporting; Formal analysis: Supporting; Investigation: Equal; Writing – original draft: Supporting; Writing – review & editing: Equal); Kara Margolis, MD (Conceptualization: Lead; Data curation: Lead; Formal analysis: Equal; Investigation: Equal; Methodology: Equal; Project administration: Lead; Supervision: Lead; Writing – original draft: Lead; Writing – review & editing: Equal).

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest The authors disclose no conflicts.

Note: To access the supplementary material accompanying this article, visit the online version of Gastroenterology at www.gastrojournal.org, and at https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2020.05.079.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Table 1.

Results in Patients With Ultrasonography or Cross-Sectional Abdominal Imaging

| Patient | Modality | Normal | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | CT | Yes | Normal-appearing bowel No inflammatory stranding or secondary signs suggestive of appendicitis Diffuse ground-glass opacities and septal thickening in the lung bases Nodular airspace opacities in the posterior dependent lobes may represent atelectasis or pneumonia |

| 2 | MRI | No | Severe concentric mural thickening, edema, and hyperenhancement of a short segment of terminal ileum with extensive mesenteric fat edema, as well as similar mural thickening in the rectosigmoid colon Ascites |

| 3 | MRI | No | Scant pelvic ascites Normal gastrointestinal tract |

| 4 | US | No | Right lower quadrant lymphadenopathy suggestive of mesenteric adenitis |

| 5 | US | No | Ascites, thick-walled gall bladder without cholecystitis |

| 6 | US | No | Sludge in gallbladder |

| 7 | US | No | Thickened bowel loops in the right lower quadrant, a prominent appendix, thickened gallbladder wall |

| 8 | US | No | Gallbladder wall thickening and pericholecystic fluid concerning for acalculous cholecystitis, small amount of free fluid |

| 9 | US | No | Nonspecific, course heterogeneous parenchymal echogenicity of the liver without focal lesions, not seen on prior US |

| 10 | US | No | Nonspecific mild bowel wall thickening in pelvis, gallbladder distended and filled with sludge, trace pelvic free fluid |

| 11 | US | No | Hepatomegaly, normal echogenicity, patent vasculature |

| 12 | US | Yes | Normal |

| 13 | US | No | Right lower quadrant mesenteric adenitis |

| 14 | US | Yes | Normal |

| 15 | US | No | Small ascites, gallbladder sludge, homogenous liver, patent hepatic vasculature |

CT, computed tomography; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; US, ultrasonography.

References

- 1.Lu X. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1663–1665. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2005073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tagarro A et al. JAMA Pediatr. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.1346. Accessed May 28, 2020.

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention https://emergency.cdc.gov/han/2020/han00432.asp

- 4.Riphagen S. Lancet. 2020;395:1607–1608. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31094-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Verdoni L. Lancet. 2020;395:1771–1778. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31103-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mao R. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;5:667–678. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(20)30126-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sultan S. Gastroenterology. 2020;159:320–334. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tullie L. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2020;4:e19–e20. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(20)30165-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]