Differential diagnosis of primary IgA nephropathy (IgAN) and IgA-dominant infection-related glomerulonephritis, particularly Staphylococcus infection−associated glomerulonephritis (SAGN), on a kidney biopsy sample can be challenging because of similar morphologic findings by light microscopy, immunofluorescence, and electron microscopy.1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 The clinical management approach, however, is very different. Immunosuppressive therapy is contraindicated in SAGN because it can lead to sepsis and even death.7 Antibiotics constitute the first line of therapy. In contrast to that, primary IgAN is treated either with conservative management or with immunosuppression.8 There are no specific biomarkers to distinguish between these 2 diseases. Sophisticated methods, such as mass spectrometry−based proteomics, have been attempted, but definitive conclusions are still lacking.6 In addition these methods are expensive, with longer turn-around time. Here we present our observations from direct immunofluorescence staining of optimal cutting temperature-embedded frozen tissue (part of the routine diagnostic workup of kidney biopsy samples), which may help to differentiate between SAGN and IgAN, if one includes in the equation IgA staining in globally sclerosed glomeruli.

We have previously published case series on our cohort of patients with culture-proven SAGN.3,6 We expanded this database by adding recent cases of SAGN (30 biopsy samples, including 1 Streptococcus mutans case) and IgAN (45 biopsy samples) (see Supplementary Methods). All 75 biopsy samples showed distinct granular staining for IgA in the nonsclerotic glomeruli (Figure 1). Globally sclerosed glomeruli were identified in 47 biopsy samples (29 with IgAN and 18 with SAGN). Among the 29 biopsy samples of IgAN, 20 (69%) had positive granular staining for IgA in the globally sclerosed glomeruli and 9 (31%) cases did not. Among the 18 kidney biopsy samples with SAGN, only 1 case (5.6%) showed positive staining for IgA in globally sclerosed glomeruli, whereas the remaining 17 (94.4%) did not (Table 1, Figure 1).

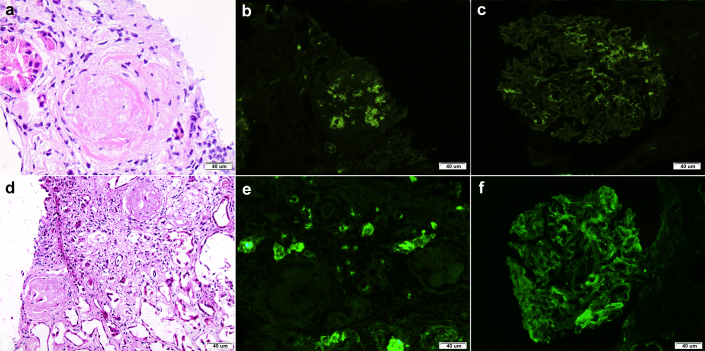

Figure 1.

Staining for IgA in kidney biopsy samples with IgA nephropathy and infection-associated glomerulonephritis. (a−c) Kidney biopsy sample from a patient with primary IgA nephropathy. (a) Globally sclerosed glomeruli were seen in the sections of frozen tissue submitted for immunofluorescence (hematoxylin-eosin stain). (b) Positive staining for IgA was seen in the sclerotic glomerulus and (c) glomeruli with open capillary loops (immunofluorescence). (d,e) Kidney biopsy sample from a patient with primary Staphylococcal infection−associated glomerulonephritis. (d) Globally sclerosed glomeruli were seen in the sections of frozen tissue submitted for immunofluorescence (hematoxylin-eosin stain). (e) Positive staining for IgA was not seen in the sclerotic glomerulus but was strongly positive in (f) glomeruli with open capillary loops (immunofluorescence). Original magnification ×200 for a, b, d, and e and ×400 for c and f.

Table 1.

Distribution of positive and negative staining for IgA in sclerotic glomeruli between cases with primary IgA nephropathy and infection-associated glomerulonephritis

| IgA staining in sclerotic glomeruli | Primary IgA nephropathy | Infection-associated glomerulonephritis | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Positive | 20 | 1 | 21 |

| Negative | 9 | 17 | 26 |

| Total | 29 | 18 | 47 |

P = 0.000001; χ2 = 18.1.

Based on these data, the sensitivity of positive IgA staining in globally sclerosed glomeruli for kidney biopsy samples with IgAN was 68.97% (confidence interval [CI], 49.17%−84.72%), and the specificity was 94.44% (CI, 72.71%−99.86%). The positive predictive value was 95.24% (CI, 74.56%−99.27%) and the negative predictive value was 65.38% (CI, 52.05%−76.67%). The positive likelihood ratio (i.e., the ratio between the probability of a positive test result given the presence of IgA nephropathy and the probability of a positive test result in SAGN) was 12.41 (CI, 1.82−84.70). Positive staining in the sclerotic glomeruli strongly favors primary IgAN. Negative staining in the sclerotic glomeruli raises the possibility of SAGN; however, considering that 31% of cases with primary IgAN also had negative staining in the sclerosed glomeruli, such a conclusion should be made with a caution.

To evaluate whether these findings are valid on formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue as well, we repeated direct immunofluorescence with proteinase antigen retrieval on formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue sections of the same biopsy samples (part submitted for light microscopy). Excluding the biopsy samples that did not have globally sclerosed glomeruli in the tissue and some older cases with background serum staining, the final cohort included 16 cases of IgAN and 8 cases of SAGN. Among these, 13 of 16 IgAN and 1 of 8 SAGN cases showed positive IgA staining in globally sclerotic glomeruli, the remaining were negative in each group, giving a sensitivity of 81.25% and specificity of 87.50%.

We had reported a significant difference in the presence of segmentally sclerosed glomeruli in kidney biopsy samples between patients with IgAN and SAGN.9 Because the current study included an expanded cohort of the previously reported patients, we reviewed the presence of segmentally sclerosed glomeruli in these biopsy samples. In the IgA nephropathy group, there were 24 cases with segmentally sclerosed glomeruli (S1 based on the MEST-C Oxford classification, where mesangial hypercellularity (M), segmental sclerosis (S), and interstitial fibrosis/tubular atrophy (T) and crescents (C) are evaluated) and 5 cases with S0. Among patients with SAGN, there were 2 cases with segmentally sclerosed glomeruli and 16 cases without segmentally sclerosed glomeruli in the tissue submitted for light microscopy (specificity, 88.89%; sensitivity, 82.76%). Our data indicate that staining in the globally sclerosed glomeruli may be another useful marker in the differentiation between IgAN and SAGN, but results should be interpreted only in the correct clinical context.

The pathogenetic mechanism behind this finding probably has to do with the temporal relationship between the onset of glomerulonephritis and glomerular sclerosis. IgAN is known to be a chronic disease with continuous or intermittent deposition of immune complexes in the glomeruli over a prolonged period of time. The incidence of IgAN peaks at a younger age1; therefore, we hypothesize that the disease started before the glomerulus became sclerosed, and the immune complex deposits persisted even after it underwent sclerosis. On the other hand, SAGN is an acute, nonrecurring disease with a predilection for older adults in whom there is already age-related pre-existing glomerular sclerosis.2, 3, 4 Therefore, immune complexes are much less likely to deposit in pre-existing globally sclerosed nonfunctioning glomeruli.

The main limitation of our study is the small number of cases. However, it is a stringently selected population of individuals with primary IgAN and culture-proven SAGN in whom the diagnosis was confirmed by a thorough clinical history and serologic and urinalysis findings. The numbers were limited also because we could include only those biopsy samples that contained globally sclerosed glomeruli in the small fraction of the biopsy sample submitted for direct immunofluorescence. The finding, however, is valid on formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue as well. We also confirmed our previous reported finding that presence of segmentally sclerosed glomeruli favors a diagnosis of primary IgAN over SAGN. We believe that evaluation of IgA staining in sclerosed glomeruli can help to differentiate between primary IgAN and SAGN in the right clinical context, and can aid in patient management in most cases.

Disclosure

All the authors declared no competing interests.

Footnotes

Supplementary Material and Methods.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Spector D.A., Millan J., Zauber N. Glomerulonephritis and Staphylococcal aureus infections. Clin Nephrol. 1980;14:256–261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yamashita Y., Tanase T., Terada Y. Glomerulonephritis after methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infection resulting in end-stage renal failure. Intern Med. 2001;40:424–427. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.40.424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Satoskar A.A., Nadasdy G., Plaza J.A. Staphylococcus infection-associated glomerulonephritis mimicking IgA nephropathy. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;1:1179–1186. doi: 10.2215/CJN.01030306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nasr S.H., Markowitz G.S., Whelan J.D. IgA-dominant acute poststaphylococcal glomerulonephritis complicating diabetic nephropathy. Hum Pathol. 2003;34:1235–1241. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(03)00424-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bu R., Li Q., Duan Z.Y. Clinicopathologic features of IgA-dominant infection-associated glomerulonephritis: a pooled analysis of 78 cases. Am J Nephrol. 2015;41:98–106. doi: 10.1159/000377684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Julian B.A., Wittke S., Haubitz M. Urinary biomarkers of IgA nephropathy and other IgA-associated renal diseases. World J Urol. 2007;25:467–476. doi: 10.1007/s00345-007-0192-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Satoskar A.A., Molenda M., Scipio P. Henoch-Schonlein purpura-like presentation in IgA-dominant Staphylococcus infection-associated glomerulonephritis–a diagnostic pitfall. Clin Nephrol. 2013;79:302–312. doi: 10.5414/CN107756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coppo R. Treatment of IgA nephropathy: recent advances and prospects. Nephrol Ther. 2018;14(Suppl 1):S13−S21. doi: 10.1016/j.nephro.2018.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Satoskar A.A., Suleiman S., Ayoub I., Hemminger J., Brodsky S.V., Bott C. Staphylococcus infection-associated glomerulonephritis-spectrum of IgA staining and prevalence of ANCA in a single-center. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;12:39–49. doi: 10.2215/CJN.05070516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.