Abstract

Neosporosis primarily affects cattle and dogs and is not currently considered a zoonotic disease. Toxoplasmosis is a zoonosis with a worldwide distribution that is asymptomatic in most cases, but when acquired during pregnancy, it can have serious consequences. The seropositivity rates determined by the indirect fluorescent antibody test for Neospora caninum (N. caninum) and Toxoplasma gondii (T. gondii) were 24.3% (49 samples) and 26.8% (54 samples), respectively. PCR positivity for N. caninum was observed in two samples of cord blood (1%) using the Nc5 and ITS1 gene, positivity for T. gondii was observed in 16 samples using the primer for the B1 gene (5.5% positivity in cord blood and 2.5% positivity in placental tissue). None of the samples showed structures characteristic of tissue cysts or inflammatory infiltrate on histopathology. Significant associations were observed only between N. caninum seropositivity and the presence of domestic animals (p = 0.039) and presence of dogs (p = 0.038) and between T. gondii seropositivity and basic sanitation (p = 0.04). This study obtained important findings regarding the seroprevalence and molecular detection of N. caninum and T. gondii in pregnant women; however, more studies are necessary to establish a correlation between risk factors and infection.

Subject terms: Molecular biology, Diseases

Introduction

Neospora caninum is an obligate intracellular parasite belonging to the phylum Apicomplexa and was first identified in 1984 in the central nervous system and skeletal muscle of dogs in Norway1. N. caninum has a wide range of hosts2,3, but neosporosis is a disease that primarily affects cattle and dogs, and canids are definitive hosts. The forms of infection are essentially the same as those of toxoplasmosis, occurring horizontally in herbivores via intake of water or foods contaminated by oocysts and in carnivores via ingestion of tissues infected with tachyzoites or tissue cysts. Vertical transmission may also occur, and N. caninum is very efficiently transplacentally transmitted in cattle, which may cause abortion2 or birth of infected and asymptomatic calves2,3.

Toxoplasma gondii can infect all warm-blooded animals, including mammals, birds, and humans4. Toxoplasmosis is an infection caused by the parasite T. gondii and may be congenital or acquired5. Intake of oocysts present in the environment and consumption of undercooked meat infected with tissue cysts are the two main forms of transmission in acquired infection5,6. Congenital transmission occurs after primary infection during pregnancy7.

The infection in most cases is asymptomatic, the mother develops temporary parasitemia. However, focal lesions can develop in the placenta, and the fetus may be infected. Slightly diminished vision is characteristic of mild disease, whereas severely all children may present with retinochoroiditis, hydrocephalus, seizures and intracerebral calcification8.

The diseases caused by T. gondii and N. caninum have similar characteristics, such as neurological conditions and reproductive pathologies, due to the morphological, genetic and immunological similarities of the two parasites9,10.

The pathological, immunological and epidemiological aspects of neosporosis in human pregnancies are still unknown, since viable N. caninum has not been isolated from human tissues so far. However, knowing that this parasite has a wide range of intermediate hosts2,3, the possibility of human infection should not be ruled out. If there is a possibility of vertical transmission in humans, we believe that the evolution and severity of the infection is dependent on the mother’s gestational age and the virulence of the strain causing the infection, as occurs in other animal species11,12.

Anti-N. caninum antibodies have been reported in humans in several studies13–16, and its zoonotic potential is still uncertain. Studies conducted with human placental tissue and umbilical cord blood for detecting N. caninum remain scarce in the literature. Therefore, the objective of this study was the molecular and serological detection of N. caninum and/or T. gondii in blood samples from the umbilical cords and placental tissues of pregnant women.

Results

The pregnant women who participated in the study had a mean age of 27.5 ± 6.022 years and were at a gestational age of 39 ± 1.4 weeks, and 13.9% of the women did not have appropriate prenatal care (28/201) as recommended by the competent organs of Brazil, which recommends six or more prenatal visits.

Serology

Of the 201 samples analyzed, 24.3% were positive for IgG anti-N. caninum antibodies (Table 1), and no sample was positive for IgM antibodies. For T. gondii, 26.8% of the samples were positive for the presence of IgG antibodies (Table 2), and no sample was positive for IgM antibodies. Of all samples analyzed, 8.4% presented seropositivity for both parasites. Western blot positive samples corroborate IFAT results, showing reactivity with 29 kDa protein (Supplementary Fig. S1). Positive samples for N. caninum in PCR, despite not being positive by IFAT, were western blot positive.

Table 1.

IFAT for IgG anti-N. caninum antibodies in cord serum.

| Neospora caninum | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of samples | IFAT (1:50) | IFAT (1:100) | IFAT (1:200) |

| +/% | +/% | +/% | |

| 201 | 49/24.3 | 9/4.4 | 3/1.4 |

Table 2.

IFAT for IgG anti-T. gondii antibodies in cord serum.

| Toxoplasma gondii | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of samples | IFAT (1:64) |

IFAT (1:128) |

IFAT (1:256) |

IFAT (1:512) |

IFAT (1:1024) |

| +/% | +/% | +/% | +/% | +/% | |

| 201 | 54/26.8 | 29/14.4 | 9/4.4 | 6/2.9 | 4/1.9 |

Statistical analyses of the N. caninum data showed significant associations (p < 0.05) between seropositivity and the presence of domestic animals and the presence of dogs. For T. gondii, a significant association (p < 0.05) between seropositivity and basic sanitation (Table 3) was observed.

Table 3.

Seroprevalence of IgG antibodies against N. caninum and T. gondii associated with risk factors for infection.

| Neospora caninum | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameters | N (%) | p value | Odds ratio (CI 95%) | |

| IgG positive | IgG negative | |||

| Age | ||||

| ≤30 | 27/132 (55.1%) | 105/132 (69.1%) | 0.102 | |

| 31–40 | 20/65 (40.8%) | 45/65 (29.6%) | — | |

| >40 | 2/4 (4.1%) | 2/4 (1.3%) | ||

| Total | 49/201 | 152/201 | ||

| Consumption of raw/undercooked meat | 11/49 (22%) | 38/49 (25%) | 0.849 | 0.868 (0.404–1.866) |

| Work or leisure activities involving soil | 5/21 (10) | 16/21 (10.5) | 0.537 | 0.896 (0.312–2.569) |

| Domestic animals | 38/130 (77.5) | 92/130 (60.5) | 0.039* | 2.253 (1.069–4.749) |

| Cat | 8/36 (16) | 28/36 (18) | 0.833 | 0.864 (0.365–2.045) |

| Dog | 35/120 (71) | 85/120 (56) | 0.038* | 1.971 (0.981–3.959) |

| Basic sanitation | 17/65 (35) | 48/65 (31.5) | 0.727 | 0.869 (0.440–1.716) |

| Toxoplasma gondii | ||||

| IgG positive | IgG negative | |||

| Age | ||||

| ≤30 | 35/132 (64.8%) | 97/132 (66%) | 0.421 | |

| 31–40 | 19/65 (35.2%) | 46/65 (31.3%) | — | |

| >40 | 0/4 (0%) | 4/4 (2.7%) | ||

| Total | 54/201 | 147/201 | ||

| Consumption of raw/undercooked meat | 41/77 (76%) | 36/77 (24.5%) | 0.555 | 0.978 (0.472–2.025) |

| Work or leisure activities involving soil | 8/21 (15) | 13/21 (9) | 0.307 | 1.698 (0.665–4.290) |

| Domestic animals | 17/110 (31) | 93/110 (63) | 0.511 | 1.224 (0.650–2.457) |

| Cat | 8/36 (15) | 28/36 (19) | 0.541 | 0.739 (0.314–1.740) |

| Dog | 37/120 (68.5) | 83/120 (56.5) | 0.145 | 1.678 (0.867–3.248) |

| Basic sanitation | 30/136 (55.5) | 106/136 (72) | 0.04* | 0.483 (0.253–0.923) |

Molecular biology

Of the 201 umbilical cord blood samples analyzed, two samples (1%) were Nc5 PCR-positive for N. caninum and these same samples were positive for ITS1 (GenBank: MN731361), but no sample of the placenta was positive.

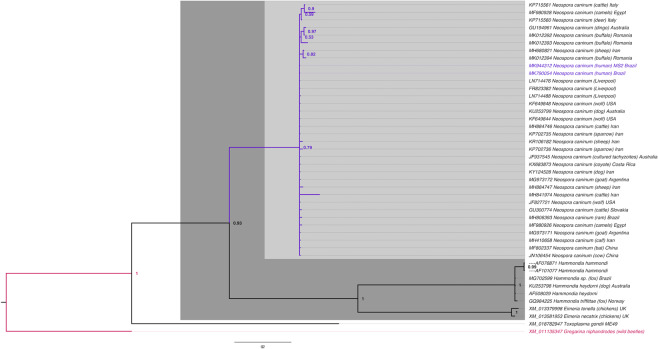

These two Nc5 gene samples were sent for sequencing, and both shared 100% similarity with each other and 100% homology for N. caninum Liverpool (GenBank: LN714476). The highest homology (98–99%) was obtained for N. caninum with strains from other countries (Fig. 1). ITS1 gene samples shared 100% homology for N. caninum Liverpool (GenBank: U16159) after sequencing.

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic tree of Neospora caninum (GenBank: MK790054; MK944312). Evolutionary history was inferred from the Bayesian Inference tree with the probability scores for the Nc5 gene. Bar, 0.2 changes per nucleotide position. The sample sequences obtained in this study are indicated in blue.

For the B1 gene of T. gondii, 16 samples presented bands compatible with the positive control in the PCR results, with 5.5% positivity in cord blood and 2.5% positivity in placental tissue. Detailed information on PCR positive samples are presented in the Supplementary Table S1.

Histopathological analysis

Histopathological analyses of 75 placenta samples (selected from among the samples showing PCR positivity and serological positive, prioritizing higher serological titles for both parasites) stained with hematoxylin-eosin were performed. These samples showed no structures characteristic of tissue cysts or inflammatory infiltrate.

Discussion

Changes in the maternal immune status occur during pregnancy to maintain fetal survival, and this immunosuppression may leave pregnant woman more prone to infections17,18. Under healthy conditions, these infections are typically kept under control during pregnancy; however, the immature immune system of the fetus leaves it vulnerable to parasites that are able to cross the uteroplacental barrier10. The transplacental hematogenic route is the most common route of maternal-fetal parasite transmission19. T. gondii and other parasites in the phylum Apicomplexa actively penetrate their host cells in vitro, and this process is also possible in vivo20.

In the present study, 24.3% seropositivity for anti-N. caninum antibodies was found, suggesting human exposure to the parasite. The seropositivity rate was higher in the present study than the rate of 5% seropositivity found by Lobato et al.13, in 91 cord blood samples. Studies by Ibrahim et al.14, found a 7.92% (8/101) seroprevalence among pregnant women for N. caninum, Tranas et al.15, found 6.7% (69/1,029) seropositivity in blood bank samples, and Oshiro et al.16, found 26.1% (81/310) positivity in HIV-positive patients. The variations in the seropositivity rates found in several studies may be attributed to the study populations and the climatic and environmental factors of each region, as some authors have reported an association between climatic factors and risk factors for N. caninum infection in cattle2,21,22. The sporulation and survival of coccidial oocysts in the environment may be favored by temperature and humidity2.

Of all the samples tested, only 8.4% presented concomitant seropositivity to T. gondii. In the literature, there have been reports of seropositivity for both parasites: Ibrahim et al.14, reported 5.94% positivity, and Oshiro et al.16, reported 25.2% positivity. However, the extent of N. caninum and T. gondii coinfection in humans is still unknown. To decrease the possibility of cross reaction, in the present study was used a serological cut off point of 1:50 and only fluorescent reactions along the periphery of the parasite were considered positive.

In a study by Paré et al.23, complete peripheral fluorescence of the parasite was considered a positive response and apical fluorescence a negative response because the conservation of antigens in the apical organelles of a variety of Apicomplexa parasites may be responsible for cross-reactivity24. Dilutions equal to or greater than 1:50 in the IFAT may be considered appropriate to avoid cross-reactivity between N. caninum and T. gondii in serum samples from some hosts13,25.

IFAT positive samples and molecular biology for N. caninum demonstrated western blot reactivity for rNcSRS2 (Nc-p43) surface antigen which is immunodominant, highly immunogenic, well conserved26 and does not cross react with T. gondii27.

The two positive PCR samples for N. caninum were not IFAT positive, but showed weak reactivity by western blot, demonstrating that western blot can be used as a complementary serological method in the diagnosis of neosporosis. In the literature there are reports of positive PCR samples that tested negative in serology tests in studies carried out with dogs28,29, and in a study carried out with bovines, in tests with aborted fetal tissues, the mother tested negative for N. caninum by IFAT and ELISA and positive by PCR, with these samples showing poor reactivity on a western blot test30.

Therefore, explanations for this fact can be attributed to the inability of some individuals to synthesize detectable antibodies against N. caninum due to acquired or innate immunotolerance30, or also to the previous chronic infection with antibodies not detectable in the 1:50 dilution28. In studies carried out with mice, it has been demonstrated the appearance of IgM antibodies after 7 days of infection by N. caninum and the production of IgG antibodies after 14 days of infection31. This reinforces the possibility of the infection being acquired at the end of pregnancy with the mother still seronegative at delivery, as with T. gondii infections32.

Samples were considered positive when Nc5 and ITS1 were positive. Of the 201 cord blood samples and 201 placental tissue samples analyzed, two cord blood samples showed PCR positivity for N. caninum using primers for the Nc5 and ITS1 region, and these samples were negative for T. gondii. After sequencing for Nc5 gene (GenBank: MK790054; MK944312), the samples demonstrated 98%-100% identity with several strains in the database, and for ITS1 gene (GenBank: MN731361) shared 100% homology for N. caninum Liverpool, suggesting that these sequences really represented samples of N. caninum. The phylogenetic tree showed a cluster of N. caninum among samples from around the world and different hosts.

Nc5 sequences were used to construct the phylogenetic tree, because unlike ITS1, the Nc5 gene is highly specific and excludes other species from the Toxoplasmatinae subfamily33, which strengthens the molecular diagnosis of the present study.

The positivity found for the Nc5 and ITS1 genes corroborate literature data. The use of nested-PCR methods directed to the Nc5 and ITS1 genes to detect N. caninum DNA may increase sensitivity and detection rate34–36.

The present study found positive molecular biology results for two umbilical cord blood samples but not for the corresponding placental samples. Because this is the first report of N. caninum in human samples, further studies are needed to clarify these findings. In studies with cows experimentally inoculated at different stages of pregnancy, some authors have reported that histopathological changes are less frequent at more advanced stages of pregnancy, suggesting that gestational age influences the outcome of placental infection37,38.

In an experimental study conducted by Ho et al.39, with pregnant monkeys (Macaca mulatta), the sporadic and inconsistent distribution of N. caninum in tissues other than those from the central nervous system was proposed to be a manifestation of constant dissemination of a small number of parasites into the bloodstream.

Human neosporosis is still an uncertain issue, despite serological evidence of human exposure, primarily in immunocompromised populations10,13,15. Considering the high efficiency and prevalence of vertical transmission of N. caninum in cattle40 and its close relationship with T. gondii, the possibility of Neospora posing a risk to human pregnancy should not be ruled out. Experimental studies with nonhuman primates indicated susceptibility to transplacental infection, and fetal lesions caused by N. caninum infection were similar to those induced by T. gondii infection41. An in vitro study has shown that human trophoblasts and cervical cells are readily infected by N. caninum, although they show differences in susceptibility to infection, cytokine production and cell viability42.

In this study, a significant association between seropositivity for N. caninum and the presence of animals as well as the presence of dogs was observed. Canids are known to be the definitive, exclusive hosts of N. caninum2. Some authors have reported that the presence of dogs on rural properties may be related to an increased likelihood of infection in cattle, thus highlighting the role of dogs in the epidemiological chain of neosporosis in farm animals43–45. Since dogs are definitive hosts and excrete oocysts in feces, the potential for human exposure to N. caninum is high14. The presence of dogs may be related to N. caninum seropositivity in the analyzed pregnant women, but additional studies in this area are necessary to establish this correlation.

In the present study, 26.8% seropositivity for anti-T. gondii IgG antibodies was observed. Being 73.1% were seronegative for the presence of IgG antibodies, and 100% were negative for IgM. According to Villard et al.46, the presence of specific IgG and the absence of IgM antibodies are indications of previous infection, however, the infection can be acquired at the end of gestation, with the mother still being seronegative at birth32. The prevalence of IgG antibodies among pregnant women in Brazil is variable, and it can reach 63.03%47–49.

A significant association was found between T. gondii seropositivity and basic sanitation (access to sewage and treated water) with p = 0.04, but no significant associations were found with other risk factors. According to Silva et al.50, a lack of basic sanitation is associated with risk factors for T. gondii infection, with low socioeconomic level, low educational level, older age, soil management and contact with cats being considered more important risk factors in pregnant women in Brazil6. In the analyzed samples, there was no significant correlation between older age and serological positivity, perhaps because the pregnant women composing the study group were young.

The use of PCR analysis in the determination of intrauterine T. gondii infection allows early diagnosis and avoids the use of invasive procedures for the fetus51. In this study, we observed 5.5% positivity in cord blood and 2.5% positivity in placental tissue for the B1 gene, even with the exclusion of acute infection confirmed by serology. Postnatal screening may be associated with the detection of these parasites in amniotic fluid, the placenta and cord or neonate serum and may be a management strategy complementary to prenatal diagnosis46.

The B1 gene has approximately 35 copies and is highly conserved in all strains52. According to Jones et al.53, primers for the B1 gene have higher specificity because they do not amplify DNA from a variety of bacterial and fungal species and because, even in the presence of increasing amounts of human DNA, the sensitivity of the reaction remains unchanged; it is able to detect 50 femtograms (corresponding to a single organism) of T. gondii DNA.

In conclusion, the seroprevalence of N. caninum can be indicative of parasite exposure, and the presence of dogs may be associated with seropositivity. Additional studies are needed to clarify possible risk factors related to N. caninum. The PCR DNA detection results indicate that the role of N. caninum in human pregnancy still needs to be elucidated in order to determine the extent and importance of human exposure, given that the parasite has thus far not been isolated from human tissues. These findings may contribute to implementation of diagnostic tests in routine prenatal screening. The seroprevalence for T. gondii in pregnant women found in the present study was low compared with that found in other regions of Brazil, and lack of basic sanitation represented an important risk factor. However, seronegativity may indicate susceptibility to infection.

Methods

Ethics statement

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee for Research Involving Human Beings of the Federal University of Mato Grosso do Sul (UFMS) on 03 November 2016, document number 1.804.047. All included patients accepted the conditions of the study and signed the free informed consent form. All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Sample collection

This study is an analytical cross-sectional study. Between January and May 2017, a total of 201 cord blood and placental tissue samples were collected from pregnant women admitted to the delivery room and surgical center of Cândido Mariano Maternity Hospital, located in Campo Grande, Mato Grosso do Sul, Brazil.

Immediately after delivery, umbilical cord blood was collected in a vacutainer tube containing K2 EDTA for molecular analysis and a clot activator tube for serological analysis. Placental fragments weighing 1–2 grams were collected from the fetal (or chorionic) and maternal ends of the placental hilus for molecular and histological analyses54.

Data were collected from the patients’ charts and from a form completed by the patients that evaluated the following variables: age, gestational age, number of prenatal consultations, problems in previous pregnancies, and living conditions and habits (consumption of raw or undercooked meat; work or leisure activities involving soil; domestic animal raising; presence of cats and/or dogs in the home; and presence of basic sanitation/access to sewage collection or treated water).

The patients included in the study were healthy pregnant women with a normal pregnancy who were in initial labor and admitted to the same maternity sector.

Serology

IFAT

The indirect fluorescent antibody test (IFAT) for the detection of anti-N. caninum antibodies was performed using an Imunoteste Neospora (RIFI) commercial diagnostic Kit (Imunodot diagnósticos, Jaboticabal-SP, Brazil) following the manufacturer’s recommendations with adaptations. Previously established positive and negative human serum controls provided by Oshiro et al., were used16. Samples were considered positive at a dilution of 1:50.

The IFAT for the detection of anti-T. gondii antibodies was performed using an Imuno-Con Toxoplasmose kit (WAMA Diagnóstica, São Carlos-SP, Brazil) following the manufacturer’s recommendations. Samples were considered positive at a dilution of 1:64.

For both serological tests of the 201 samples, human anti-IgG and anti-IgM fluorescence conjugate at 1:100 dilution (conjugated with fluorescein isothiocyanate; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, Missouri, USA) were used. The slides were observed using a fluorescence-equipped microscope (Axioskop- Carl Zeiss, Germany) (epi-lighting system) with a 40× objective.

Fluorescent reactions along the periphery of the parasite were considered positive. In the negative reactions, the parasites on the slide did not show fluorescence, or the fluorescence was located at only one end, characterized as polar coloration or an apical reaction. Samples with peripheral fluorescence of total tachyzoites were considered positive23.

Western blot

N. caninum rNcSRS2 partial recombinant sequence (Nc-p43)55 protein was separated on 12% SDS-PAGE gel and transferred to PVDV membrane (GE Healthcare, UK) at 25 mA overnight (Supplementary Protocols S1).

Molecular biology

DNA isolation

Approximately 300 microliters (µl) of cord blood from each sample (201 total) and 50 milligrams of placental tissue from each sample (201 total) were subjected to DNA extraction using a protocol adapted from Regitano and Coutinho56 (Supplementary Protocols S1).

Samples were quantified via spectrophotometry (NanoDrop ND-1000, Uniscience) and diluted to 100 nanograms for PCR. The viability of the samples and DNA quality were evaluated using primers for the human β-globin gene as described by Bauer et al.57.

PCR for neospora caninum and toxoplasma gondii

For detection of N. caninum, the primers NP21 and NP4 were used for the primary amplification and primers NP7 and NP4 were used in the secondary reactions to target the Nc5 gene as described by Yamage et al.33. Primers for internal transcribed spacer (ITS1) region was used out with four oligonucleotides as described by Buxton et al.58–60 (Supplementary Protocols S1).

For detection of T. gondii, was used primer to perform simple PCR targeting the repetitive and conserved B1 gene61, a nested PCR was also performed using N2-C2 primers, which amplified a 97-bp product of the B1 gene62 (Supplementary Protocols S1).

Negative (ultrapure water) and positive (N. caninum NC‐1 strain and T. gondii RH strain) controls were included with all PCR reactions. To increase the sensitivity of the assay, each DNA sample was tested in triplicate.

The final product was visualized on a 1.5% agarose gel stained with ethidium bromide (EtBr).

Samples yielding an expected PCR product size for N. caninum were purified using a PureLink quick gel extraction kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and DNA-sequenced at René Rachou Research Center (Oswaldo Cruz Foundation-FIOCRUZ) in an automatic sequencer (ABI Prism 3730XL Genetic Analyzer, Applied Biosystems, EUA) with a 48-capillary DNA analysis system.

Phylogenetic tree construction

Using the BLASTn program, sequences available from GenBank was aligned with the sequence of the Nc5 gene (GenBank: MK790054; MK944312). The Mega 6.0 program63 was used to align the sequences taken from GenBank and construct a database that contained all similar sequences obtained from the analysis. Using the MrBayes 3.2.6 program was performed a Bayesian phylogenetic analysis for the Nc5 gene and the results were plotted using the FigTree 1.4.2 program64–66.

The topology of the tree was used to generate a 50% majority rule consensus, with the percentage of samples recovering any particular clade representing the posterior probability of a clade (1 = 100%). No manual editing of the tree was performed. The Gregarina niphandrodes (GenBank: XM_011135347) dataset was used as the outgroup in the phylogenetic tree.

Histopathological analysis

Fragments of placental samples weighing 1 to 2 grams collected during delivery were immediately fixed in 10% buffered formalin for 24 hours, processed (xylol alcohol), embedded in paraffin, sliced into a final thickness of 5 µm and placed on a slide for hematoxylin-eosin staining. The slides were visualized at 400X magnification to examine placental morphology.

Statistical analysis

The collected data were tabulated and analyzed using the statistical software IBM SPSS Statistics version 20 (Inc., Chicago, Illinois, USA). The χ2 test, Fisher’s exact test and odds ratios were used to assess associations between the variables (consumption of raw/undercooked meat, work or leisure activities involving soil, domestic animals, cat, dog, basic sanitation) and the serology results. p values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

This study was financed in part by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior – Brasil (CAPES) Finance Code 001. This study was financed in part by the Fundação Universidade Federal de Mato Grosso do Sul – UFMS/MEC – Brazil. The authors thank the Program for Technological Development in Tools for Health-PDTISFIOCRUZ for use of its facilities.

Author contributions

D.P.O. performed the experiments and wrote and edited the manuscript; O.L.M. and D.D.M. performed the experiments and conceptualized the study; Z.N.P. and C.B.G. performed the data analysis and statistical analyses; A.R. and C.J.B. acquired funding for the research, provided the study materials, and conceptualized the study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41598-020-65991-1.

References

- 1.Bjerkfis I, Mohn SF, Presthus J. Unidentified cyst-forming sporozoon causing encephalomyelitis and myositis in dogs. Z. Parasitenkd. 1984;70:271–74. doi: 10.1007/BF00942230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dubey, J. P., Schares, G. & Ortega-Mora, L. M. Epidemiology and control of neosporosis and Neospora caninum. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 20, 323–67, 10.1128%2FCMR.00031-06 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Dubey JP, Lindsay DS. A review of Neospora caninum and neosporosis. Vet. Parasitol. 1996;67:1–59. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4017(96)01035-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tenter AM, Heckeroth AR, Weiss LM. Toxoplasma gondii: from animals to humans. Int. J. Parasitol. 2000;30:1217–58. doi: 10.1016/S0020-7519(00)00124-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dubey JP. Advances in the life cycle of Toxoplasma gondii. Int. J. Parasitol. 1998;28:1019–24. doi: 10.1016/S0020-7519(98)00023-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dubey JP, Lago EG, Gennari SM, Su C, Jones JL. Toxoplasmosis in humans and animals in Brazil: high prevalence, high burden of disease, and epidemiology. Parasitol. 2012;139:1375–1424. doi: 10.1017/S0031182012000765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lindsay DS, Dubey JP. Toxoplasma gondii: the changing paradigm of congenital toxoplasmosis. Parasitol. 2011;138:1829–31. doi: 10.1017/S0031182011001478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hill D, Dubey JP. Toxoplasma gondii: transmission, diagnosis and prevention. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2002;8:634–40. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-0691.2002.00485.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hemphill A, Fuchs N, Sonda S, Hehl A. The antigenic composition of Neospora caninum. Int. J. Parasitol. 1999;29:1175–88. doi: 10.1016/S0020-7519(99)00085-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barratt, J. L. N., Harkness, J., Marriott, D., Ellis, J. T. & Stark, D. Importance of nonenteric protozoan infections in immunocompromised people. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 23, 795–836, 10.1128%2FCMR.00001-10 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Buxton D, McAllister MM, Dubey JP. The comparative pathogenesis of neosporosis. Trends Parasitol. 2002;18:546–52. doi: 10.1016/S1471-4922(02)02414-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Al-Qassab SE, Reichel MP, Ellis JT. On the biological and genetic diversity in Neospora caninum. Diversity. 2010;2:411–38. doi: 10.3390/d2030411. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lobato J, et al. Detection of immunoglobulin G antibodies to Neospora caninum in humans: high seropositivity rates in patients who are infected by human immunodeficiency virus or have neurological disorders. Clin. Vaccine. Immunol. 2006;13:84–9. doi: 10.1128/CVI.13.1.84-89.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ibrahim HM, et al. Prevalence of Neospora caninum and Toxoplasma gondii antibodies in northern Egypt. Am. J. Trop. Med. hyg. 2009;80:263–67. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2009.80.263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tranas J, Heinzen RA, Weiss LM, McAllister MM. Serological evidence of human infection with the protozoan Neospora caninum. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 1999;6:765–67. doi: 10.1128/CDLI.6.5.765-767.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oshiro LM, et al. Neospora caninum and Toxoplasma gondii serodiagnosis in human immunodeficiency virus carriers. Rev. Soc. Bras. Med. Trop. 2015;48:568–72. doi: 10.1590/0037-8682-0151-2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yip L, McCluskey J, Sinclair R. Immunological aspects of pregnancy. Clin. Dermatol. 2006;24:84–7. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2005.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weetman AP. The immunology of pregnancy. Thyroid. 1999;9:643–46. doi: 10.1089/thy.1999.9.643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carlier Y, Truyens C, Deloron P, Peyron F. Congenital parasitic infections: a review. Acta. Trop. 2012;121:55–70. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2011.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dobrowolski JM, Sibley LD. Toxoplasma invasion of mammalian cells is powered by the actin cytoskeleton of the parasite. Cell. 1996;84:933–39. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81071-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rinaldi L, et al. Neospora caninum in pastured cattle: determination of climatic, environmental, farm management and individual animal risk factors using remote sensing and geographical information systems. Vet. Parasitol. 2005;128:219–30. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2004.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wouda W, Bartels CJM, Moen AR. Characteristics of Neospora caninum-associated abortion storms in dairy herds in The Netherlands (1995 to1997) Theriogenology. 1999;52:233–45. doi: 10.1016/s0093-691x(99)00125-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Paré J, Hietala SK, Thurmond MC. Interpretation of an indirect fluorescent antibody test for diagnosis of Neospora sp. infection in cattle. J. Vet. Diagn. Investig. 1995;7:273–75. doi: 10.1177/104063879500700310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Taylor DW, Evans CB, Aley SB, Barta JR, Danforth HD. Identification of an apically located antigen that is conserved in sporozoan parasites. J. Protozool. 1990;37:540–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.1990.tb01262.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Silva DA, Lobato J, Mineo TW, Mineo JR. Evaluation of serological tests for the diagnosis of Neospora caninum infection in dogs: optimization of cut off titers and inhibition studies of crossreactivity with Toxoplasma gondii. Vet. Parasitol. 2007;143:234–44. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2006.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Howe DK, Crawford AC, Lindsay D, Sibley LD. The p29 and p35 immunodominant antigens of Neospora caninum tachyzoites are homologous to the family of surface antigens of Toxoplasma gondii. Infect. Immun. 1998;66:5322–28. doi: 10.1128/IAI.66.11.5322-5328.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hemphill A. Subcellular localization and functional characterization of Nc-p43, a major Neospora caninum tachyzoite surface protein. Infect. Immun. 1996;64:4279–87. doi: 10.1128/IAI.64.10.4279-4287.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pena HFDJ, et al. Isolation and molecular detection of Neospora caninum from naturally infected sheep from Brazil. Vet. Parasitol. 2007;147:61–66. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2007.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lindsay DS, Dubey JP, Duncan RB. Confirmation that the dog is a definitive host for Neospora caninum. Vet. Parasitol. 1999;82:327–33. doi: 10.1016/S0304-4017(99)00054-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sager H, et al. A Swiss case–control study to assess Neospora caninum-associated bovine abortions by PCR, histopathology and serology. Vet. Parasitol. 2001;102:1–15. doi: 10.1016/S0304-4017(01)00524-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Teixeira L, et al. Characterization of the B-cell immune response elicited in BALB/c mice challenged with Neospora caninum tachyzoites. Immunol. 2005;116:38–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2005.02195.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sensini A. Toxoplasma gondii infection in pregnancy: opportunities and pitfalls of serological diagnosis. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2006;12:504–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2006.01444.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yamage M, Flechtner O, Gottstein B. Neospora caninum: specific oligonucleotide primers for the detection of brain “cyst” DNA of experimentally infected nude mice by the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) J. Parasitol. 1996;82:272–79. doi: 10.2307/3284160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gui BZ, et al. First report of Neospora caninum infection in pigs in China. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2019;00:1–4. doi: 10.1111/tbed.13358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang X, et al. Detection of Neospora caninum DNA by polymerase chain reaction in bats from Southern China. Parasitol. Int. 2018;67:389–91. doi: 10.1016/j.parint.2018.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Salehi N, Gottstein B, Haddadzadeh HR. Genetic diversity of bovine Neospora caninum determined by microsatellite markers. Parasitol. Int. 2015;64:357–61. doi: 10.1016/j.parint.2015.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ogino H, et al. Neosporosis in the aborted fetus and newborn calf. J. Comp. Pathol. 1992;107:231–37. doi: 10.1016/0021-9975(92)90039-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Macaldowie C, et al. Placental pathology associated with fetal death in cattle inoculated with Neospora caninum by two different routes in early pregnancy. J. Comp. Pathol. 2004;131:142–56. doi: 10.1016/j.jcpa.2004.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ho MS, et al. Detection of Neospora from tissues of experimentally infected rhesus macaques by PCR and specific DNA probe hybridization. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1997;35:1740–45. doi: 10.1128/JCM.35.7.1740-1745.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Davison HC, Otter A, Trees AJ. Estimation of vertical and horizontal transmission parameters of Neospora caninum infections in dairy cattle. Int. J. Parasitol. 1999;29:1683–89. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7519(99)00129-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Barr BC, Conrad PA, Sverlow KW, Tarantal AF, Hendrickx AG. Experimental fetal and transplacental Neospora infection in the nonhuman primate. Lab. Invest. 1994;71:236–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Carvalho JV, et al. Differential susceptibility of human trophoblastic (BeWo) and uterine cervical (HeLa) cells to Neospora caninum infection. Int. J. Parasitol. 2010;40:1629–37. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2010.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schares G, et al. Potential risk factors for bovine Neospora caninum infection in Germany are not under the control of the farmers. Parasitol. 2004;129:301–9. doi: 10.1017/s0031182004005700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Guimarães JS, Jr., Souza SLP, Bergamaschi DP, Gennari SM. Prevalence of Neospora caninum antibodies and factors associated with their presence in dairy cattle of the north of Paraná state, Brazil. Vet. Parasitol. 2004;124:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2004.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wouda W, Dijkstra T, Kramer AM, van Maanen C, Brinkhof JM. Seroepidemiological evidence for a relationship between Neospora caninum infections in dogs and cattle. Int. J. Parasitol. 1999;29:1677–82. doi: 10.1016/S0020-7519(99)00105-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Villard O, et al. Serological diagnosis of Toxoplasma gondii infection: recommendations from the French National Reference Center for Toxoplasmosis. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2016;84:22–33. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2015.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.da Silva MG, Vinaud MC, de Castro AM. Prevalence of toxoplasmosis in pregnant women and vertical transmission of Toxoplasma gondii in patients from basic units of health from Gurupi, Tocantins, Brazil, from 2012 to 2014. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0141700. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0141700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lopes-Mori FM, et al. Gestational toxoplasmosis in Paraná State, Brazil: prevalence of IgG antibodies and associated risk factors. Braz. J. Infect. Dis. 2013;17:405–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bjid.2012.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Reis MM, Tessaro MM, D’Azevedo PA. Serologic profile of toxoplasmosis in pregnant women from a public hospital in Porto Alegre. Rev. Bras. Ginecol. Obstet. 2006;28:158–64. doi: 10.1590/S0100-72032006000300004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.da Silva MG, Câmara JT, Vinaud MC, de Castro AM. Epidemiological factors associated with seropositivity for toxoplasmosis in pregnant women from Gurupi, State of Tocantins, Brazil. Rev. Soc. Bras. Med. Trop. 2014;47:469–75. doi: 10.1590/0037-8682-0127-2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Montoya JG. Laboratory diagnosis of Toxoplasma gondii infection and toxoplasmosis. J. Infect. Dis. 2002;185:S73–S82. doi: 10.1086/338827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cazenave J, Cheyrou A, Blouin P, Johnson AM, Begueret J. Use of polymerase chain reaction to detect Toxoplasma. J. Clin. Pathol. 1991;44:1037. doi: 10.1136/jcp.44.12.1037-a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jones CD, Okhravi N, Adamson P, Tasker S, Lightman S. Comparison of PCR detection methods for B1, P30, and 18S rDNA genes of T. gondii in aqueous humor. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2000;41:634–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Duarte PO, et al. Neonatal sepsis: evaluation of risk factors and histopathological examination of placentas after delivery. Biosci. J. 2019;35:629–39. doi: 10.14393/BJ-v35n2a20198-41814. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lima Junior MSDC, Andreotti R, Caetano AR, Paiva F, Matos MDFC. Cloning and expression of an antigenic domain of a major surface protein (Nc-p43) of Neospora caninum. Rev. Bras. Parasitol. Vet. 2007;16:61–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Regitano, L. C. A., Coutinho, L. L. Biologia molecular aplicada à produção animal, Brasília: Embrapa Informação Tecnológica (2001).

- 57.Bauer HM, et al. Genital human papillomavirus infection in female university students as determined by a PCR-based method. JAMA. 1991;265:472–77. doi: 10.1001/jama.1991.03460040048027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Buxton D, et al. The pathogenesis of experimental neosporosis in pregnant sheep. J. Comp. Pathol. 1998;118:267–79. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9975(07)80003-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bartley PM, et al. Detection of Neospora caninum DNA in cases of bovine and ovine abortion in the South-West of Scotland. Parasitol. 2019;146:979–82. doi: 10.1017/S0031182019000301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hecker Yanina P., Morrell Eleonora L., Fiorentino María A., Gual Ignacio, Rivera Emilia, Fiorani Franco, Dorsch Matías A., Gos María L., Pardini Lais L., Scioli María V., Magariños Sergio, Paolicchi Fernando A., Cantón Germán J., Moore Dadín P. Ovine Abortion by Neospora caninum: First Case Reported in Argentina. Acta Parasitologica. 2019;64(4):950–955. doi: 10.2478/s11686-019-00106-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Burg JL, Grover CM, Pouletty P, Boothroyd JC. Direct and sensitive detection of a pathogenic protozoan, Toxoplasma gondii, by polymerase chain reaction. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1989;27:1787–92. doi: 10.1128/JCM.27.8.1787-1792.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Spalding SM, Amendoeira MRR, Coelho JMC, Angel SO. Otimização da reação de polimerase em cadeia para detecção de Toxoplasma gondii em sangue venoso e placenta de gestantes. J. Bras. Med. Patol. Lab. 2002;38:105–10. doi: 10.1590/S1676-24442002000200006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tamura K, Stecher G, Peterson D, Filipski A, Kumar S. MEGA6: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis version 6.0. Mol Biol Evol. 2013;30:2725–29. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ronquist F, Huelsenbeck JP. MrBayes 3: Bayesian phylogenetic inference under mixed models. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:1572–74. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tree Bio. FigTree [online]. London: Tree Bio; 2016 [cited 2019 November 10]. Available from, http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/figtree/.

- 66.Csordas BG, et al. New insights from molecular characterization of the tick Rhipicephalus (Boophilus) microplus in Brazil. Rev. Bras. Parasitol. Vet. 2016;25:317–26. doi: 10.1590/S1984-29612016053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.