Abstract

Objective:

User-centered design can improve engagement with and the potential efficacy of behavioral interventions, but is underutilized in healthcare. This work demonstrates how design methodologies can inform the design of a mobile behavioral intervention for binge eating and obesity.

Method:

A needs assessment was conducted with end-users [N = 22 adults with obesity and recurrent binge eating (≥12 episodes in 3 months) who were interested in losing weight and addressing binge eating], which included assessing participants’ past/current and future willingness to engage with 20 treatment targets for managing binge eating and weight. Targets focused on improving dietary intake, increasing physical activity, and reducing overvaluation of weight and/or shape, unhealthy weight control practices, and negative affect.

Results:

Participants’ past and current use of targets varied. For all targets except those addressing unhealthy weight control practices, on average, participants had increasing levels of willingness to try targets. Among participants not currently using a target, at least some were willing to use every target again.

Discussion:

Findings inform ways to personalize how users begin treatment. Further, this study exemplifies how user-centered design can inform ways to ensure digital interventions are designed to meet end-users’ needs to improve engagement and clinical impact.

Keywords: user-centered design, binge eating, obesity, treatment targets, mobile, intervention, needs assessment

Introduction

Up to 30% of treatment-seeking adults with obesity engage in binge eating (Dingemans, Bruna, & van Furth, 2002; Mitchell et al., 2015; Wilfley, Citrome, & Herman, 2016), and individuals with binge eating disorder commonly present to treatment with the goal of losing weight (Brody, Masheb, & Grilo, 2005). We are designing a mobile behavioral intervention to address obesity and binge eating simultaneously. In addition to addressing the standard tenants of behavioral weight loss treatment – namely, improving dietary intake and increasing physical activity (Wilfley, Hayes, Balantekin, Van Buren, & Epstein, 2018) – we theorize that reducing overvaluation of weight and/or shape, unhealthy weight control practices, and/or negative affect will be beneficial, as these constructs affect binge eating and weight gain (Byrne, LeMay-Russell, & Tanofsky-Kraff, 2019; Goldschmidt, 2017). To help individuals achieve improvements in these theoretical constructs, we identified 20 potential corresponding treatment targets (“targets;” see Table 1).

Table 1.

Participant Past Use of Targets and Future Willingness to Try

| Theoretical Construct | Treatment Target | Past/Current Use | Starting Today, I am… | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Do Not Know | Never Used | Previous Use | Continued Use | Need More Info | Not Willing | Likely Not Willing | Somewhat Willing | Willing | ||

| Dietary Intake | Eat meals and snacks at the same time each day. | 0% | 27% | 55% | 18% | 9% | 5% | 18% | 14% | 55% |

| Avoid eating snacks that you didn’t plan to eat. | 5% | 23% | 45% | 27% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 14% | 86% | |

| Plan for the meals you’ll eat this week. | 0% | 5% | 55% | 41% | 9% | 5% | 5% | 27% | 55% | |

| Find a buddy who will help you eat more healthfully. | 0% | 32% | 27% | 41% | 0% | 18% | 5% | 14% | 64% | |

| Eat smaller portions. | 0% | 0% | 32% | 68% | 0% | 0% | 5% | 14% | 82% | |

| Eat more fruits and vegetables. | 0% | 0% | 18% | 82% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 18% | 82% | |

| Eat less fast food. | 0% | 0% | 23% | 77% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 9% | 91% | |

| Construct Average | 1% | 12% | 36% | 51% | 3% | 4% | 5% | 16% | 73% | |

| Physical Activity | Regularly do physical activity (~3x/week), like walking, riding a bike, or going to the gym (unless a doctor has said it is not appropriate/healthy for you to exercise right now). | 0% | 0% | 32% | 68% | 0% | 5% | 5% | 18% | 73% |

| Have less “screen time,” like watching less TV and spending less time on your computer, tablet, or phone. | 5% | 55% | 32% | 9% | 5% | 9% | 32% | 32% | 23% | |

| Find a buddy who will help you be more physically active. | 0% | 9% | 41% | 50% | 0% | 18% | 5% | 9% | 68% | |

| Construct Average | 2% | 21% | 35% | 42% | 2% | 11% | 14% | 20% | 55% | |

| Overvaluation of Weight and/or Shape | When you notice yourself criticizing something about your body, stop yourself. Ask yourself: What is the evidence that the criticism is true or not true? Then, think of a more balanced conclusion you can draw about your body. | 5% | 45% | 14% | 36% | 0% | 5% | 5% | 32% | 59% |

| List out things you like and value about yourself as a person. Remind yourself of things that are more important to you than how your body looks or how much you weigh. | 0% | 50% | 23% | 27% | 0% | 5% | 9% | 23% | 64% | |

| Avoid spending time in front of the mirror pointing out things you think of as your “flaws.” | 5% | 36% | 14% | 45% | 0% | 5% | 0% | 36% | 59% | |

| Stop yourself when you dwell on “feeling fat.” Tell yourself that “fat” is not a feeling, and instead say something to yourself that is not self-blaming or self-shaming. | 0% | 50% | 27% | 23% | 0% | 0% | 5% | 27% | 68% | |

| Construct Average | 2% | 21% | 19% | 33% | 0% | 3% | 5% | 30% | 63% | |

| Unhealthy Weight Control Practices | Avoid skipping meals or going for long stretches of time without eating. | 0% | 14% | 45% | 41% | 0% | 14% | 0% | 9% | 77% |

| Avoid “dieting” and cutting out certain types of foods. | 0% | 23% | 41% | 36% | 5% | 5% | 14% | 23% | 55% | |

| Try eating one serving of a food that you’ve been avoiding because you consider it a “trigger” food for binge eating. | 0% | 59% | 18% | 23% | 5% | 5% | 5% | 36% | 50% | |

| Construct Average | 0% | 32% | 35% | 33% | 3% | 8% | 6% | 23% | 61% | |

| Negative Affect | Do activities that make you happy and do not involve food. | 0% | 9% | 18% | 73% | 0% | 0% | 5% | 0% | 95% |

| Notice times when you’re feeling down, and find something that makes the situation feel a bit better. | 0% | 14% | 32% | 55% | 0% | 0% | 5% | 5% | 91% | |

| Ask a friend or loved one to do something enjoyable together. Or repair a relationship in which you had a disagreement or falling out. | 0% | 23% | 27% | 50% | 5% | 5% | 5% | 23% | 64% | |

| Construct Average | 0% | 15% | 26% | 59% | 2% | 2% | 5% | 9% | 83% | |

Before designing the mobile intervention, however, we sought to learn whether people who represented the intended users of the intervention (“end-users”) would be willing to engage with these targets. User-centered design provides a methodology for engaging with end-users to understand their needs and preferences by making users the center of the design process. Through collaborative and iterative engagement with end-users, user-centered design helps to make technological systems easier to understand, navigate, and evaluate (Graham et al., 2019; Norman, 1988). Design approaches are gaining traction for health-related interventions (e.g., Jacobs, Clawson, & Mynatt, 2014; Miller & Mynatt, 2014; Patwardhan et al., 2015; Tendedez, McNaney, Ferrario, & Whittle, 2018; Toscos, Faber, An, & Gandhi, 2006), making this methodology ripe for informing an intervention for obesity and binge eating.

By placing users at the center of the design process, researchers refrain from making assumptions about the user experience, but rather learn about it directly from users (Norman & Draper, 1986). Consistent with this process, we conducted a needs assessment to understand end-users’ experiences managing weight and binge eating. This research included assessing ways in which end-users have previously engaged with the proposed targets for managing weight and binge eating, their current engagement with these targets, and their willingness to implement these targets in the future, which is the focus of the current analysis.

Methods

Participants & Procedure

Participants were recruited via dscout, an online research platform that has over 100,000 members who can complete screeners to be considered for research opportunities. For this study, dscout screen respondents were eligible if they were non-pregnant, English-speaking adults (≥18 years), had obesity [body mass index (BMI) ≥30], engaged in recurrent binge eating (≥12 episodes in the past 3 months), were interested in reducing binge eating and losing weight, and were willing to use an app to address these problems.

Of those eligible, 25 individuals (the allowable sample size for our study within dscout, and which we anticipated would be sufficient to achieve saturation for qualitative analyses; Glaser & Strauss, 1999) were selected based on race/ethnicity, gender, and age to capture diverse perspectives. These individuals were invited to participate in a 4-week study to describe their experiences with obesity and binge eating, and ideas for managing eating and weight. Of the invited sample, 22 participants completed the study and are included in the analyses. Though this sample size is small for quantitative research and precludes conducting statistical analyses, it is consistent with research in the human-computer interaction field, in which the most commonly published sample size is 12 and the majority of studies (70%) report sample sizes less than 30 (Caine, 2016).

Participants received $100 for completing the full needs assessment. This paper focuses on the subset of data that assessed participants’ past, current, and future willingness to engage with the 20 targets. Participants were given four days to complete this portion of activities.

This study was approved by the Northwestern University Institutional Review Board, and all participants provided online informed consent.

Measures

On two consecutive occasions, participants were presented a list of the 20 targets. On the first presentation, for each target, participants were asked to indicate if they (a) have never used it (“never used”); (b) have used it in the past, but not anymore (“previous use”); (c) have used it in the past, and continue to use it currently (“continued use”); or (d) don’t understand what it is or know if they have used it (“do not know”). On the second presentation, participants were asked to rate their willingness to try each target by responding to the prompt “Starting today, I…” (a) am willing to try it (“willing”); (b) am somewhat willing to try it (“somewhat willing”); (c) am likely not going to try it (“likely not willing”); (d) am not at all willing to try it (“not willing”); or (e) would need to know more about it to figure out if I am willing to try it (“need more info”).

Analyses

For each target, the proportion of participants who selected each response was calculated, separately for past/current use and for future willingness. For each response option, averages were calculated across targets within a theoretical construct. We also explored participants’ future willingness to try targets that they previously used but were not currently practicing (i.e., calculated only among those who indicated previous use). For each target, responses were combined into “willing” (willing plus somewhat willing), “unwilling” (likely not willing plus not willing), and “need more information.”

Results

Sample Characteristics

Mean age was 37.0 years (SD = 10.2); 36% identified as male. Participants identified as 32% non-Hispanic White, 27% Black, 27% Hispanic, 9% Asian/Pacific Islander, and 5% unknown. At screening, mean BMI was 37.1 (SD = 5.4; range = 30.3 – 49.4) and mean number of binge episodes was 20.5 (SD = 7.3; range = 12 – 35).

Past and Current Use

The average proportions of participants who endorsed previous and current use of each target are presented in Table 1 (columns 3–6). Within each theoretical construct, average patterns of past and current use of targets varied. For targets associated with dietary intake, the average proportion of participants who understood and used the targets increased from “do not know” (1%) to “continued use” (51%). A similar within-construct pattern was observed for negative affect (from 0% “do not know” to 59% “continued use”) and physical activity (from 2% “do not know” to 42% “continued use”). However, for overvaluation of weight and/or shape, the proportion of participants who used the targets differed, in that “never used” (21%) surpassed “previous use” (19%). Averages for unhealthy weight control practices were relatively consistent across the “never used” (32%), “previous use” (35%), and “continued use” (33%) responses.

Comparing participants’ average responses across theoretical constructs, the constructs in which “continued use” of targets was most frequently endorsed were negative affect (59%), dietary intake (51%), and physical activity (42%). Targets associated with overvaluation of weight and/or shape were least frequently endorsed as “continued use” (33%). Overall, there were very few targets (n = 4 targets) that participants did not understand. The most commonly used target was “eat more fruits and vegetables” (endorsed as “continued use” by 82% of participants), followed by “eat less fast food” (77%) and “do activities that make you happy” (73%).

Future Use

Participants’ ratings of their willingness to use targets in the future are presented in the five right-most columns of Table 1. For all theoretical constructs except unhealthy weight control practices, participants’ responses increased gradually across response categories, with “need more info” having the lowest average responses and “willing” having the highest average responses. However, for unhealthy weight control practices, more participants were “not willing” (8%) than “likely not willing” (6%) to try the targets, although “willing” still elicited the highest response (consistent with the other theoretical constructs). Overvaluation of weight and/or shape was the only theoretical construct in which no participants indicated they needed more information.

On average, willingness to try targets was highest for negative affect (83%), dietary intake (73%), and overvaluation of weight and/or shape (63%). On average, participants were least willing to try targets related to physical activity (11%) and unhealthy weight control practices (8%).

Overall, participants were most willing to do the targets: “do activities that make you happy” (95%), “when down, do something that makes you feel better” (91%), and “eat less fast food” (91%). The target with the fewest willing to try responses was “have less screen time” (22%). Participants were least willing to “find a buddy who will help you eat more healthfully” (18%), “find a buddy who will help you be more physically active” (18%), and “avoid going for long stretches of time without eating” (14%). The targets with the highest percentage of participants (nearly 10%) who needed more information were “eat meals and snacks at the same time each day” and “plan for meals you will eat this week.”

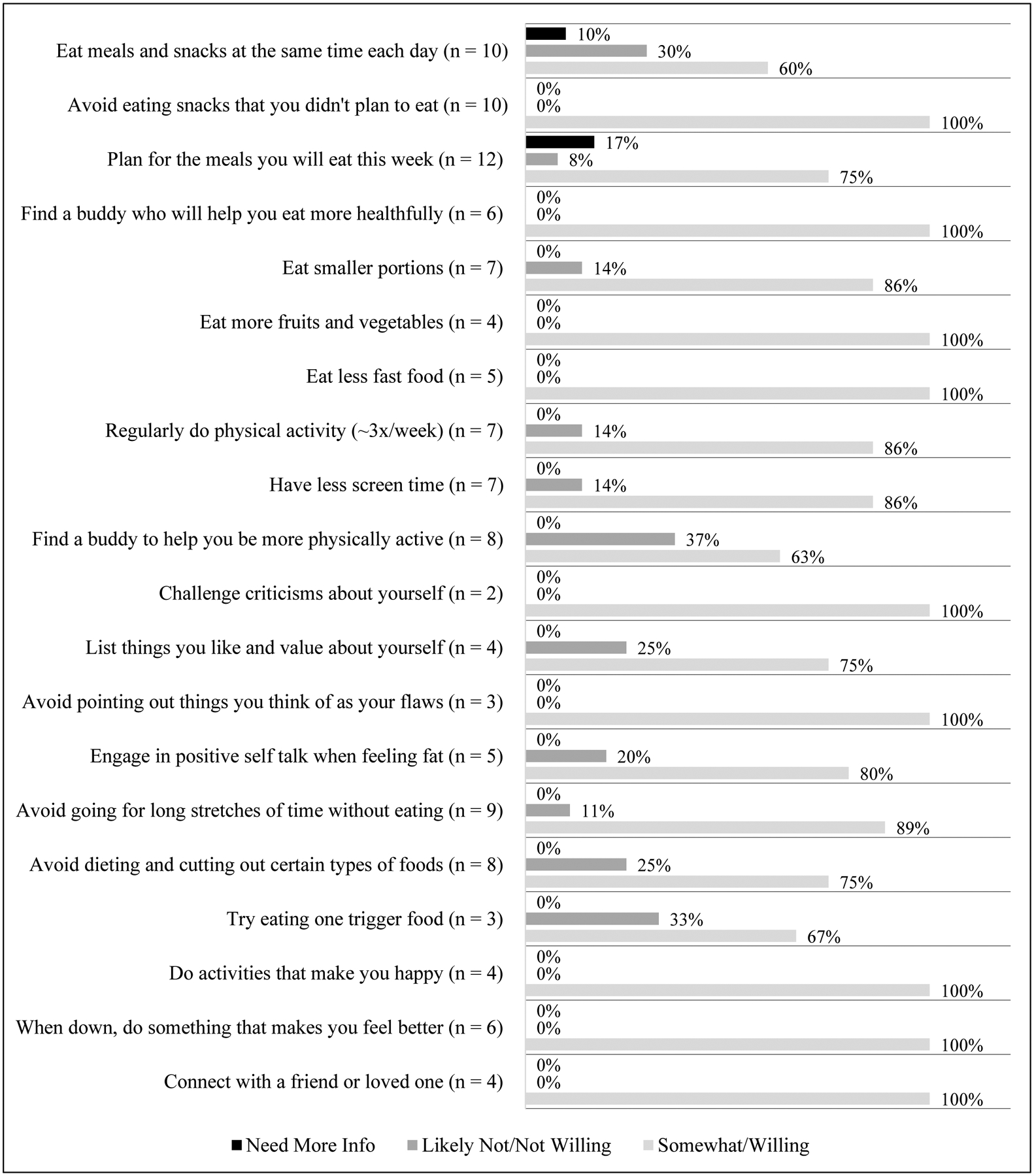

Willingness to Try Treatment Targets Used Previously

Figure 1 shows which targets people were willing versus unwilling to use, based on previous but not current target use. At least some participants were willing to try every target again. All participants were willing to re-try: “avoid eating snacks that you didn’t plan to eat,” “find a buddy who will help you eat more healthfully,” “eat more fruits and vegetables,” “eat less fast food,” “challenge criticisms about yourself,” “avoid pointing out things you think of as your flaws,” “do activities that make you happy,” “when down, do something that makes you feel better,” and “connect with a friend or loved one.” However, a subset of participants was unwilling to try certain targets again. Participants were least willing to re-try: “eat meals and snacks at the same time each day” (30%), “find a buddy to help you be more physically active” (37%), and “eat one trigger food” (33%). Even though they endorsed previous use, some participants needed more information for “eat meals and snacks at the same time each day” (n = 1) and “plan for the meals you will eat this week” (n = 2).

Figure 1.

Future willingness/unwillingness to use treatment targets among those reporting previous but not current use.

Note: Some treatment target names have been condensed for space, and the full names are listed in Table 1; treatment targets are presented in the same order in the Figure and Table.

Discussion

We conducted a needs assessment that included exploring end-users’ past, current, and future willingness to engage with 20 potential targets for managing binge eating and obesity. Several design implications emerged.

Given participants’ range of experiences using targets, findings illuminate potential benefits of aligning intervention recommendations with users’ past experiences and future goals. For example, participants were most willing to engage and re-engage in activities that helped with negative affect, suggesting that addressing this construct early on may foster engagement. All participants were willing to re-engage with targets related to improving dietary intake and reducing overvaluation of weight/shape, despite not currently using the targets. These targets could also be good to address early in treatment because users may have the least resistance to them. Additionally, many participants were already working on improving dietary intake, meaning it could be beneficial to emphasize maintenance of associated targets rather than introducing them as new concepts. By contrast, though many participants had not practiced reducing unhealthy weight control practices, a substantial proportion were willing to do so. Designs that support users in working on targets in this area could be beneficial. Finally, participants were least willing, on average, to pursue physical activity targets. Given the importance of physical activity for weight management (Jakicic, Rogers, Davis, & Collins, 2018), additional design efforts may be needed to inform how to engage users in these goals.

Taken together, this work provides an example of applying user-centered design to efficiently learn end-users’ needs and preferences before unnecessarily devoting resources to developing a mobile intervention that may not be engaging to users. However, the study’s small sample size precludes making generalizable conclusions about these specific targets or empirically comparing past/current and future use. Moreover, it is unknown whether participants’ self-reported willingness to use targets translates to actual future behaviors. Future research is needed to test whether those who report willingness to try targets actually do so and to validate the design recommendations presented here on the mobile intervention’s engagement and clinical impact.

Funding Source:

This work was supported a grant from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (K01 DK116925).

Availability of Data Statement: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

- Brody ML, Masheb RM, & Grilo CM (2005). Treatment preferences of patients with binge eating disorder. Int J Eat Disord, 37(4), 352–356. doi: 10.1002/eat.20137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrne ME, LeMay-Russell S, & Tanofsky-Kraff M (2019). Loss-of-Control Eating and Obesity Among Children and Adolescents. Curr Obes Rep, 8(1), 33–42. doi: 10.1007/s13679-019-0327-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caine K (2016). Local Standards for Sample Size at CHI. Paper presented at the Proceedings of the 2016 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, San Jose, California, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Dingemans AE, Bruna MJ, & van Furth EF (2002). Binge eating disorder: a review. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord, 26(3), 299–307. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801949 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser BG, & Strauss AL (1999). Discovery of Grounded Theory. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Goldschmidt AB (2017). Are loss of control while eating and overeating valid constructs? A critical review of the literature. Obes Rev, 18(4), 412–449. doi: 10.1111/obr.12491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham AK, Wildes JE, Reddy M, Munson SA, Barr Taylor C, & Mohr DC (2019). User-centered design for technology-enabled services for eating disorders. Int J Eat Disord, 52(10), 1095–1107. doi: 10.1002/eat.23130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs ML, Clawson J, & Mynatt ED (2014). My journey compass: a preliminary investigation of a mobile tool for cancer patients. Paper presented at the Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Toronto, Ontario, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Jakicic JM, Rogers RJ, Davis KK, & Collins KA (2018). Role of Physical Activity and Exercise in Treating Patients with Overweight and Obesity. Clin Chem, 64(1), 99–107. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2017.272443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller AD, & Mynatt ED (2014). StepStream: a school-based pervasive social fitness system for everyday adolescent health. Paper presented at the Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Toronto, Ontario, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell JE, King WC, Courcoulas A, Dakin G, Elder K, Engel S, … Wolfe B (2015). Eating behavior and eating disorders in adults before bariatric surgery. Int J Eat Disord, 48(2), 215–222. doi: 10.1002/eat.22275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norman DA (1988). The psychology of everyday things: Basic books. [Google Scholar]

- Norman DA, & Draper SW (1986). User centered system design: New perspectives on human-computer interaction: CRC Press. [Google Scholar]

- Patwardhan M, Stoll R, Hamel DB, Amresh A, Gary KA, & Pina A (2015). Designing a mobile application to support the indicated prevention and early intervention of childhood anxiety. Paper presented at the Proceedings of the conference on Wireless Health, Bethesda, Maryland. [Google Scholar]

- Tendedez H, McNaney R, Ferrario M-A, & Whittle J (2018). Scoping the Design Space for Data Supported Decision-Making Tools in Respiratory Care: Needs, Barriers and Future Aspirations. Paper presented at the Proceedings of the 12th EAI International Conference on Pervasive Computing Technologies for Healthcare, New York, NY, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Toscos T, Faber A, An S, & Gandhi MP (2006). Chick clique: persuasive technology to motivate teenage girls to exercise. Paper presented at the CHI ‘06 Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Montréal, Québec, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Wilfley DE, Citrome L, & Herman BK (2016). Characteristics of binge eating disorder in relation to diagnostic criteria. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat, 12, 2213–2223. doi: 10.2147/ndt.s107777 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilfley DE, Hayes JF, Balantekin KN, Van Buren DJ, & Epstein LH (2018). Behavioral interventions for obesity in children and adults: Evidence base, novel approaches, and translation into practice. Am Psychol, 73(8), 981–993. doi: 10.1037/amp0000293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]