Abstract

Background:

Few data exist regarding the rate of inferior vena cava (IVC) filter retrieval among brain-injured patients.

Methods:

We conducted a retrospective cohort study using inpatient claims between 2009 and 2015 from a nationally representative 5% sample of Medicare beneficiaries. We included patients aged ≥65 years who were hospitalized with acute brain injury. The primary outcome was the retrieval of IVC filter at 12 months and the secondary outcomes were the association with 30-day mortality and 12-month freedom from pulmonary embolism (PE). We used Current Procedural Terminology codes to ascertain filter placement and retrieval and International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification codes to ascertain venous thromboembolism (VTE) diagnoses. We used standard descriptive statistics to calculate the crude rate of filter placement. We used Cox proportional hazards analysis to examine the association between IVC filter placement and mortality and the occurrence of PE after adjustment for demographics, comorbidities, and mechanical ventilation. We used Kaplan-Meier survival statistics to calculate cumulative rates of retrieval 12 months after filter placement.

Results:

Among 44 641 Medicare beneficiaries, 1068 (2.4%; 95% confidence interval [CI], 2.3%-2.5) received an IVC filter, of whom 452 (42.3%; 95% CI, 39.3%-45.3) had a diagnosis of VTE. After adjusting for demographics, comorbidities, and mechanical ventilation, filter placement was not associated with a reduced risk of mortality (hazard ratio [HR], 1.0; 95% CI, 0.8-1.3) regardless of documented VTE. The occurrence of pulmonary embolism at 12 months was associated with IVC filter placement (HR, 3.19; 95% CI, 1.3-3.3) in the most adjusted model. The cumulative rate of filter retrieval at 12 months was 4.4% (95% CI, 3.1%-6.1%); there was no significant difference in retrieval rates between those with and without VTE.

Conclusions:

In a large cohort of Medicare beneficiaries hospitalized with acute brain injury, IVC filter placement was uncommon, but once placed, very few filters were removed. IVC filter placement was not associated with a reduced risk of mortality and did not prevent future PE.

Keywords: brain injury, intracranial hemorrhage, inferior vena cava filter, health services research, deep venous thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, neurocritical care

Background

Inferior vena cava (IVC) filters are used with the goal of preventing pulmonary embolism (PE) due to the migration of deep venous thrombosis (DVT).1-4 Guidelines recommend placement of IVC filters in patients with venous thromboembolism (VTE) and a contraindication to anticoagulation,5,6 but the benefits of IVC filters have not been clearly elucidated in randomized trials.3,7 Their overall use has increased,8,9 but there is widespread variation in use among the general medical population.10-12 Inferior vena cava filters are also associated with a variety of complications.3,7 Furthermore, although most filters are meant to be temporary, only 10% to 30% are actually removed in clinical practice in the general medical population,13-15 which may be problematic as complication rates are highest with prolonged insertion.7,15 Patients with acute brain injury, including traumatic brain injury (TBI) and intracranial hemorrhage (ICH), face a high risk of VTE, and clinicians often hesitate to use anticoagulant drugs in these patients given a high risk of intracranial hemorrhage.16,17 Thus, IVC filters are highly utilized in this specific population.16,18 However, there are few population-level data on the use of IVC filters in patients with acute brain injury. We aimed to identify IVC filter usage patterns in neurologic patients who are at high risk of intracranial hemorrhage from anticoagulation use. We hypothesized that IVC filter use in this population is for secondary prevention of VTE, that IVC filter use is associated with a mortality benefit, and that there is a low rate of IVC filter retrieval.

Methods

Design

We performed a retrospective cohort study using inpatient and outpatient claims between 2009 and 2015 from a nationally representative 5% sample of Medicare beneficiaries. The US federal government’s Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) provide health insurance to a large majority of US residents once they reach 65 years of age. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services make available to researchers data on claims submitted by providers and hospitals in the course of Medicare beneficiaries’ clinical care.19 Claims data from hospitals include International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) diagnosis and procedure codes and dates of hospitalization. Physician claims include ICD-9-CM codes, Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes, the dates of service, and physicians’ specialty. Multiple claims for a given patient can be linked via a unique beneficiary identifier code, thus allowing for a comprehensive and longitudinal analysis of each beneficiary’s care over time. We limited our cohort to beneficiaries with continuous coverage in traditional fee-for-service Medicare (both parts A and B) for at least 1 year (or until death, if applicable) and no participation in a Medicare Advantage plan. We follow the Guidelines on The Report of Studies Conducted Using Observational Routinely Collected Health Data.20 The data used in this analysis include restricted Medicare claims data and therefore cannot be directly shared because of the terms of the data use agreement. However, investigators can obtain access to these data by application to the CMS.

Patient Population

We included patients aged ≥65 years who were hospitalized with TBI or ICH defined as intracerebral, subarachnoid, or subdural hemorrhage. Diagnoses were ascertained from validated ICD-9-CM codes for TBI (800-801.9, 803.0-804.9, 850-854.1, 959.01), intracerebral hemorrhage (431), subdural hemorrhage (432.1), and subarachnoid hemorrhage (430).21,22 For patients with multiple qualifying hospitalizations, we selected the first hospitalization as the index hospitalization. We excluded patients who had a documented IVC filter placement prior to their index hospitalization.

Measurements

The primary outcome was IVC filter placement and retrieval. Secondary outcomes included VTE diagnosis prior to filter placement, 30-day mortality, and freedom from PE following placement.

Current Procedural Terminology codes were used to ascertain IVC filter placement (37191, 37620, or 35940) and retrieval (37193 or 37203), as done in prior studies.12 We included any IVC filter placements that occurred during the index hospitalization or up to 30 days after discharge since in some facilities these procedures are preferentially done on an urgent outpatient basis.

Using previously validated ICD-9-CM codes, we ascertained the diagnoses of VTE, defined as a composite of PE or DVT, before and during the index hospitalization.18,23,24 For each physician claim for IVC filter placement, we ascertained whether VTE was the procedural indication for IVC filter placement.

The CMS beneficiaries’ denominator file was used to ascertain age, sex, self-reported race, and the date of death, if applicable. We used standard ICD-9-CM codes to ascertain Charlson comorbidities.25 A previously validated ICD-9-CM code was used to ascertain mechanical ventilation26 as a proxy for illness severity.

Statistical Analysis

We used standard descriptive statistics with proportions and exact confidence intervals (CIs) to calculate crude rates of IVC filter placement. To examine the association between IVC filter placement and association with mortality within 30 days of hospital discharge, we treated IVC filter placement as a time-varying covariate, and we used Cox proportional hazards models to adjust for demographics, Charlson comorbidities, and mechanical ventilation. These variables were chosen a priori based on biological plausibility. Subgroup analyses were performed among patients with and without VTE. We used Kaplan-Meier survival statistics to calculate cumulative rates of IVC filter retrieval at 3, 6, and 12 months after filter placement. The log-rank test was used to compare retrieval rates among patients with and without documented VTE during the index hospitalization. We used Kaplan-Meier analysis at 3 or 12 months to investigate the probability of freedom from PE using Kaplan-Meier analysis at 3 or 12 months in patients with and without IVC filter. Analyses were conducted using Stata/MP version 14 (College Station, Texas), and the threshold of statistical significance was set at an α of .05.

Results

We identified 44 641 Medicare beneficiaries who were hospitalized with TBI, ICH, subdural hemorrhage, or subarachnoid hemorrhage and had no prior documentation of IVC filter placement. Among this cohort, 1068 (2.4%; 95% CI, 2.3-2.5) received an IVC filter. Patients who underwent IVC filter placement were more often male, more often black, were younger, and had a higher burden of comorbidities (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Medicare Beneficiaries With Traumatic Brain Injury or Intracranial Hemorrhage Stratified by Placement of IVC Filter, 5% National Sample.

| Characteristics | IVC Filter (N = 1068) | No IVC Filter (N = 43 573) |

|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD), years | 80.3 (7.9) | 77.6 (7.3) |

| Female | 539 (50.5)a | 24 231 (55.6) |

| Venous thromboembolism | 452 (42.3) | 2055 (4.72) |

| Inpatient placement of IVC filter | 741 (69.4) | NA |

| Mechanical ventilation | 283 (26.5) | 6132 (14.07) |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index, mean (SD) | 2.8 (1.6) | 2.5 (1.7) |

| Charlson comorbidities | ||

| Myocardial infarction | 135 (12.6) | 5120 (11.8) |

| Coronary heart failure | 249 (23.3) | 10 431 (23.9) |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 120 (11.2) | 5167 (11.9) |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 932 (87.3) | 31 234 (71.7) |

| Dementia | 55 (5.2) | 3181 (7.3) |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 259 (24.3) | 10 241 (23.5) |

| Rheumatologic disease | 46 (4.31) | 1609 (3.7) |

| Peptic ulcer disease | 15 (1.4) | 749 (1.7) |

| Liver disease | 15 (1.4) | 869 (2.0) |

| Diabetes | 430 (40.3) | 16 877 (39.7) |

| Renal disease | 212 (19.9) | 9067 (20.8 |

| Malignancy | 218 (20.4) | 5825 (13.4) |

| Metastatic solid tumor | 97 (9.1) | 1660 (3.8) |

Abbreviations: IVC, inferior vena cava; SD, standard deviation.

a Data are presented as number (%) unless otherwise specified.

Among the 1068 patients who underwent IVC filter placement, 452 (42.3%; 95% CI, 39.3-45.3) had either a documented prior history of VTE or a VTE diagnosis during their index hospitalization. The physician performing the IVC filter placement documented a diagnosis of VTE as the procedural indication in 302 cases (28.3%; 95% CI, 25.6-31.1). Inferior vena cava filter placement was substantially more common among those with VTE (18.0%; 95% CI, 16.5-19.6) compared to those without documented VTE (1.5%; 95% CI, 1.3-1.6). Similarly, those with a remote history of VTE prior to the index hospitalization were more likely to undergo IVC filter placement (12.1%; 95% CI, 10.5-13.8) than those without VTE (2.0%; 95% CI, 1.9-2.2).

Among the 44 641 patients in our cohort, 6045 (13.5%; 95% CI, 13.2-13.9) died within 30 days of discharge from their hospitalization. Inferior vena cava filter placement was associated with a higher risk of mortality (hazard ratio [HR], 1.5; 95% CI, 1.2-1.9), and this association remained unchanged after adjustment for demographic characteristics (HR, 1.5; 95% CI, 1.2-1.9) and additionally for comorbidities (HR, 1.4; 95% CI, 1.1-1.8), but there was no longer any association after additional adjustment for mechanical ventilation (HR, 1.0; 95% CI, 0.8-1.3).

In this most adjusted model, there was no association between IVC filter placement and mortality in those without documented VTE (HR, 1.0; 95% CI, 0.7-1.4) or in those with VTE (HR, 0.9; 95% CI, 0.6-1.2).

Pulmonary embolism occurred in 924 patients in the year following index admission. There was an association between IVC filter placement and PE occurrence (HR, 2.7; 95% CI, 1.8-4.4). In the most adjusted model for demographic characteristics, comorbidities, and mechanical ventilation, PE remained associated with IVC placement (HR, 3.19; 95% CI, 1.3-3.3). Earlier timing of IVC filter placement during index hospitalization did not associate with a lower risk of PE in adjusted models (HR, 1.8; 95% CI, 1.2-2.9) when compared with outpatient placement (HR, 1.5; 95% CI, 1.0-2.4).

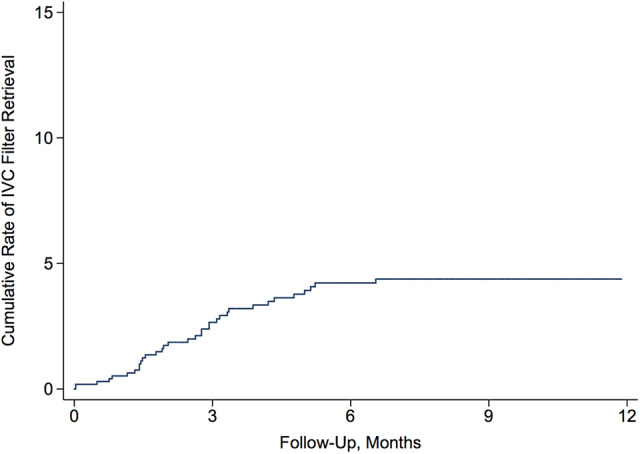

During a mean follow-up period of 1.7 (±1.8) years after IVC filter placement, the cumulative rates of retrieval was 2.7% (95% CI, 1.8%-4.0%) at 3 months, 4.2% (95% CI, 3.0%-5.9%) at 6 months, and 4.4% (95% CI, 3.1%-6.1%) at 1 year (Figure 1). There was no significant difference in retrieval rates between those with and without VTE.

Figure 1.

Cumulative rate of removal of inferior vena cava filters placed in medicare beneficiaries with acute brain injury.

Discussion

In a large cohort of Medicare beneficiaries hospitalized with TBI or ICH, approximately 1 in 40 patients underwent IVC filter placement. Filter placement was more common in patients with VTE, and fewer than 1 in 20 of these IVC filters were retrieved. Less than half of the patients who received an IVC filter had a documented diagnosis of VTE. Inferior vena cava filter placement was associated with an increased risk of mortality after adjustment for demographics and comorbidities, although the association disappeared after adjusting for a proxy for the severity of brain injury. Recent retrospective literature similarly showed an increased mortality risk in patients with IVC filter placement in whom anticoagulation is contraindicated18 and no mortality in benefit in prospective trials.27 The lack of association with mortality when adjusting for brain injury severity proxy might imply that IVC filter placement is itself a marker for more severe brain injury, occurring in those patients with longer length of stays and longer mechanical ventilation days. Alternatively, it can be interpreted to mean that patients with a contraindication to anticoagulation with lower extremity DVT do not derive a substantial benefit from IVC filter placement.

Inferior vena cava filter placement was not associated with freedom from PE at 1 year, which is consistent with recent findings that early prophylactic IVC filter placement does not lower the incidence of PE or death at 3 months.27

The only randomized trial of filter placement excluded patients with contraindication to anticoagulation therapy.4,28 In the absence of strong evidence, treatment decisions for these patients, many of whom have contraindications for anticoagulant therapy, require clinician judgment. A retrospective data found that IVC filters reduced the risk of early death in patients with contraindication to anticoagulation, although there was a subsequent increased risk of DVT in these patients and no decreased risk of PE at 1 year.29 Few data exist regarding IVC filter use in brain-injured patients, who are particularly susceptible to both thrombotic and bleeding events. In this context, our study provides novel information on nationwide patterns of use and outcomes of IVC filter placement in this uniquely vulnerable population.

The optimal use of anticoagulation in brain-injured patients remains unknown. A recent meta-analysis of observational studies examining anticoagulation reinitiation at a median of 10 to 39 days from the time of intracerebral hemorrhage found a significantly lower risk of thromboembolic events and a similar rate of hemorrhage recurrence.30 However, no randomized trials have addressed the therapeutic dilemma of whether and when to start anticoagulation in brain-injured patients with VTE. In this context, the lack of mortality reduction in patients with IVC filters and the infrequent retrieval once placed raise concerns about the use of IVC filters as an alternative form of VTE prophylaxis or treatment for those thought to be ill-fit for anticoagulation.

Our study should be considered within the context of several limitations. First, the use of administrative claims data may have subjected our ascertainment of diagnoses and outcomes to misclassification bias; however, we used validated codes for our diagnoses and outcomes.12,18,21-23 Second, CPT codes do not distinguish between permanent and retrievable filters, so the true retrieval rate is likely about one-fifth higher given that about 20% of filters placed are permanent.31 Third, we lacked data on patients’ medication use, and thus we were unable to place our results in the context of anticoagulant use. This would have an effect on the decision to remove and timing of removal of the IVC filter. Fourth, we lacked clinical data on the severity of brain injury and thus were unable to adjust for, perhaps, the strongest determinant of mortality in our patient population. Therefore, our analyses of the association between IVC filter placement and mortality are simply cautionary and are not meant to be in any way conclusive.

Conclusion

In a large, heterogeneous population of patients with acute brain injury, we found low overall rates of IVC filter placement. Most filters appeared to be the placement for primary rather than secondary prevention of VTE. In imperfectly adjusted models, we found no association between filter placement and reduced mortality. Furthermore, we found suboptimal practices regarding IVC filter use in which very few filters were eventually retrieved. Given the paucity of rigorous data on the efficacy and safety of IVC filters for this population, our results highlight the need for more robust data and suggest caution in the meantime when considering using IVC filters.

Footnotes

Authors’ Note: K.M. contributed project development, data collection, data analysis, and manuscript writing/editing; M.L.C. contributed project development and manuscript writing/editing; M.A-.K., H.L.K., and A.B. contributed in manuscript writing/editing; H.K. contributed in project development, data collection, data analysis, and manuscript editing. Statistical analyses performed by H.K. This study was approved by the Weill Cornell Medical College institutional review board. The need for human subject consent was waived.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The authors declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Hooman Kamel receives nonfinancial support outside this work from BMS-Pfizer Alliance and Roche Diagnostics as protocol PI of the ARCADIA trial. He additionally serves as a steering committee member of Medtronic’s Stroke AF trial and serves on an advisory board for Roivant Sciences.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Hooman Kamel is supported by NIH grants K23NS082367, R01NS097443, and U01NS095869 as well as by the Michael Goldberg Research Fund.

ORCID iD: Hooman Kamel, MD  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5745-0307

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5745-0307

References

- 1. Greenfield LJ, Michna BA. Twelve-year clinical experience with the Greenfield vena caval filter. Surgery. 1988;104(4):706–712. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hyers TM, Agnelli G, Hull RD, et al. Antithrombotic therapy for venous thromboembolic disease. Chest. 1998;114(5 suppl):561s–578s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Streiff MB. Vena caval filters: a comprehensive review. Blood. 2000;95(12):3669–3677. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Decousus H, Leizorovicz A, Parent F, et al. A clinical trial of vena caval filters in the prevention of pulmonary embolism in patients with proximal deep-vein thrombosis. prevention du risque d’embolie pulmonaire par interruption cave study group. N Engl J Med. 1998;338(7):409–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Minichiello T. Efforts to optimize patient benefit from inferior vena cava filters: comment on “Retrieval of inferior vena caval filters after prolonged indwelling time”. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(21):1955–1956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kearon C, Akl EA, Ornelas J, et al. Antithrombotic therapy for VTE disease: CHEST guideline and expert panel report. Chest. 2016;149(2):315–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Yost MD, Klaas JP. Paradoxical embolism in the setting of inferior vena cava filter removal. Vasc Med. 2017;22(5):440–441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Duszak R, Parker L, Levin DC, Rao VM. Placement and removal of inferior vena cava filters: national trends in the medicare population. J Am Coll Radiol. 2011;8(7):483–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bikdeli B, Wang Y, Minges KE, et al. Vena caval filter utilization and outcomes in pulmonary embolism: medicare hospitalizations from 1999 to 2010. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;67(9):1027–1035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. White RH, Geraghty EM, Brunson A, et al. High variation between hospitals in vena cava filter use for venous thromboembolism. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(7):506–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Meltzer AJ, Graham A, Kim J-H, et al. Clinical, demographic, and medicolegal factors associated with geographic variation in inferior vena cava filter utilization: an interstate analysis. Surgery. 2013;153(5):683–688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Brown JD, Raissi D, Han Q, Adams VR, Talbert JC. Vena cava filter retrieval rates and factors associated with retrieval in a large US cohort. J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;6(9). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sarosiek S, Crowther M, Sloan JM. Indications, complications, and management of inferior vena cava filters: the experience in 952 patients at an academic hospital with a level I trauma center. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(7):513–517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Angel LF, Tapson V, Galgon RE, Restrepo MI, Kaufman J. Systematic review of the use of retrievable inferior vena cava filters. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2011;22(11):1522–1530.e1523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Friedell ML, Nelson PR, Cheatham ML. Vena cava filter practices of a regional vascular surgery society. Ann Vasc Surg. 2012;26(5):630–635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Skaf E, Stein PD, Beemath A, Sanchez J, Bustamante MA, Olson RE. Venous thromboembolism in patients with ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke. Am J Cardiol. 2005;96(12):1731–1733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Goldstein JN, Fazen LE, Wendell L, et al. Risk of thromboembolism following acute intracerebral hemorrhage. Neurocrit Care. 2009;10(1):28–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Turner TE, Saeed MJ, Novak E, Brown DL. Association of inferior vena cava filter placement for venous thromboembolic disease and a contraindication to anticoagulation with 30-day mortality. JAMA Netw Open. 2018;1(3):e180452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Xiao G, Zhu S, Xiao X, Yan L, Yang J, Wu G. Comparison of laboratory tests, ultrasound, or magnetic resonance elastography to detect fibrosis in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a meta-analysis. Hepatology. 2017;66(5):1486–1501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Benchimol EI, Smeeth L, Guttmann A, et al. The REporting of studies Conducted using Observational Routinely-collected health Data (RECORD) statement. PLoS Med. 2015;12(10):e1001885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Tirschwell DL, Longstreth WT. JrJr. Validating administrative data in stroke research. Stroke. 2002;33(10):2465–2470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Morris NA, Merkler AE, Parker WE, et al. Adverse outcomes after initial non-surgical management of subdural hematoma: a population-based study. Neurocrit Care. 2016;24(2):226–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sanfilippo KM, Wang TF, Gage BF, Liu W, Carson KR. Improving accuracy of International Classification of Diseases codes for venous thromboembolism in administrative data. Thromb Res. 2015;135(4):616–620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. White RH, Gettner S, Newman JM, Trauner KB, Romano PS. Predictors of rehospitalization for symptomatic venous thromboembolism after total hip arthroplasty. N Engl J Med. 2000;343(24):1758–1764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45(6):613–619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. De Coster C, Li B, Quan H. Comparison and validity of procedures coded With ICD-9-CM and ICD-10-CA/CCI. Med Care. 2008;46(6):627–634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ho KM, Rao S, Honeybul S, et al. A multicenter trial of vena cava filters in severely injured patients. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(4):328–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Mismetti P, Laporte S, Pellerin O, et al. Effect of a retrievable inferior vena cava filter plus anticoagulation vs anticoagulation alone on risk of recurrent pulmonary embolism: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2015;313(16):1627–1635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. White RH, Brunson A, Romano PS, Li Z, Wun T. Outcomes after vena cava filter use in noncancer patients with acute venous thromboembolism: a population-based study. Circulation. 2016;133(21):2018–2029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Murthy SB, Gupta A, Merkler AE, et al. Restarting anticoagulant therapy after intracranial hemorrhage: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Stroke. 2017;48(6):1594–1600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kim HS, Young MJ, Narayan AK, Hong K, Liddell RP, Streiff MB. A comparison of clinical outcomes with retrievable and permanent inferior vena cava filters. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2008;19(3):393–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]