Abstract

Anchote (Coccinia Abyssinica) starch films were prepared by a solution casting method with glycerol, 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium acetate, sorbitol ortriethylene glycol as plasticizers. The effect of these plasticizers and their concentration on film microstructure, thermal, and mechanical properties was investigated. Scanning electron microscopy revealed that regardless of plasticizer type, films possessing higher plasticizer content had more homogeneous morphologies than those with lower plasticizer content.The FTIR spectra of films plasticized with 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium acetate had higher intensity peaks at 3150, 1400 and 1000 cm−1 when compare to other film peaks. These datashow that 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium acetate plasticized films have decreased molecular order which results in less hydrogen bonding. For this reason, films developed from 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium acetate were more flexible than the others. The effect of plasticizers on the thermal properties of the anchote starch films was investigated using thermogravimetric analysis (TGA). Films made from 30%(w/w) plasticizer concentration exhibited higher thermal stability for all types of plasticizer. Mechanical testing showed that sorbitol films had the highest tensile strength,approximately 2 times that of thetriethylene glycol plasticized filmand 3 times that of the film made from 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium acetate.

Keywords: Anchote, Starch, Thermoplastic

1. Introduction

Thermoplastic starch (TPS) isa candidate as a naturally renewable thermoplastic materialas starch is one of the most abundant and inexpensive biopolymers[1,2]. However, in comparison with conventional petroleumoil based plastic films, TPS films are hydrophilic, brittle in dry atmosphere, and lose mechanical strength as well as barrier properties in high humidity [3]. Furthermore, recrystallization phenomena or retrogradation of TPS occurs during storagethatresults in changing functional properties of the film [4]. Various studies have tried to address these limitations through blending starch with natural and synthetic polymers, adding fillers and reinforcing agents to TPS [5,6].Native starch does not possess thermoplastic characteristics and exists in granular form. TPS is made by applying thermal and mechanical energy on the starch granules in the presence of plasticizers [4]. Plasticizers improve film flexibility by reducing the internal hydrogen bonding between polymer chains while increasing free volume. The effect of the plasticizer depends on their structural similarity with the polymer [1,3]. The functional properties of TPS materials depends on additives used in TPS preparation, and processing conditions including time, temperature, mechanical shear, and plasticizer type as well as amount [2,6].

Glycerol is a commonly used plasticizer for making thermoplastic starch films. There are a number of chemicals used as plasticizers such as glycols, formamide, urea, citric or mellic acid, polyols, and others[4]. The most common polyols are glycerol, sorbitol, and polyethylene glycol [7]. Their use is due to their ability to minimize cracking of the films during storage and handling [1]. Different researchers have investigated the effect of polyols as plasticizer in the development of TPS films[8–11]. On the other hand, ionic liquids, which are salts melt below 100 °C, have the ability to dissolve polysaccharides making them excellent starch plasticizers [12].

In addition to using starch for thermoplastic starch or biodegradable materials, it has been utilized for manufacturing of cleaning products, textile sizing agents, food and beverages, cosmetics, adhesives, coating and other applications [13–15]. Due to broad applicability, availability, renewability and environmental advantages there is demand on the market for starch. As such, research to identify “novel” and “underutilized” crops for starch remains important[16–18]. These non-conventional starches were tested for various applications and demonstrated promising results [16]. Anchote starch can be considered as an “underutilized” starch. It is extracted from anchote (Cocciniaabyssinica) tuber crop which is indigenous to Ethiopia.

No reports are available on the potential use of anchote (Cocciniaabyssinica) starch to produce TPS films or bioplastic materials..We recently reported the starch physicochemical characteristics of anchotestarchwhich had comparible physicochemical properties butenhanced thermal stability when compared to commercially available wheat and potato starches[18]. Therefore, it is possible to develop thermoplastic starch materials from anchote starch. However, the functional properties of TPS materials depends on the structure of starch which is directly related with the origin of starch [4]. As anchote starch comes from a different origin and it is indigenous to specific area, here we study TPS materials from Anchote starch to investigate the TPS material functional properties.The present study aims to investigate the effects of different plasticizers, such as glycerol, 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium acetate, sorbitol, and triethylene glycol as well astheir concentration variation on anchote starch films and we report upon the morphological, thermal, and mechanical properties and the effect of plasticizers on these properties for anchote starch films.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Anchote (Coccinia Abyssinica) starch was used in this research. Anchote tuber was obtainedfrom the local market at Nekemet, Oromia Region, Ethiopia. The anchote starch was extracted from the tuber using a modified literature procedure[19]. The plasticizers, such as glycerol, 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium acetate, sorbitol andtriethylene glycol, were purchased from Sigma Aldrich and used as received.

2.2. Film Preparation

Films were prepared using a solution casting method [20]. The film forming solution was made by adding 3 grams of anchote starch powder in 100 mL of distilled water with a plasticizer concentration of 30%, or40% (w/w) of dry starch. The dispersion of anchote starch and distilled water was maintained for 20 min at 85 °C ±2 °Cunder magnetic stirring, and the plasticizer was added and kept for an additional 10 min. The resulting film forming solution was cooled to a temperature of 65 °C. 35 mL of the film forming solution was poured intoa10 cm diameter plastic petri dishes. The films were dried at 50 °C in an oven for 24 h. The dried films were peeled manually and kept for at least 48 h in desiccators containing a saturated solution of Mg(NO3)2 prior to the film characterization.

2.3. Film Characterization

2.3.1. Film thickness and density

The film thickness was measured using a digital micrometer to thenearest of 0.01 mm. The film thickness was measured at six random locations in three different samples and is reported as their average film thickness. The film density was determined according to literature procedure [21]. Films were cut into 20 × 20 mm squares, and film thickness was measured with six random measurements. Then the samples were dried at 110 °C for 24 h and weighed. The density was calculated as the ratio of weight to volume.

2.3.2. Moisture content and solubility in water

Moisture content was determined according to the standard method D644–99 (ASTM, 1999). The film was cut into rectangular piece and kept at 105 °C for 24 h in an oven. Then the moisture content was calculated from the weight loss.The water solubility of films was determined according to aliterature procedure [22]. Film samples were first dried at 105 °C for 24 h to determine the initial dry weight (W1). Then the dried samples were immersed in 30 mL of distilled water in 50 mL beaker with gentle stirring for 24 h. Finally, the samples were dried in an oven at 105 °C for 24 h to determine the final dry weight (W2). The water solubility (WS) of the sample was calculated as follows:

| (1) |

2.3.3. Scanning electron microscopy

The cross sectional microstructure of the films was observed using Field Emission Scanning Electron Microscope (JSM-6500F, JEOL Ltd., Japan). The films were cryofractured using liquid nitrogen and then put on the support using double sided adhesive tape. The fracture surface was coated with a 5 nm thick coating of gold using a sputter coater (Desk II, Denton Vacuum) and examined with the acceleration voltage of 5KV and a 10 mm of working distance.

2.3.4. FTIR

The infrared spectra were measured using Fourier transform infrared spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific Instrument Co., USA) the film sample was placed in the sample holder and the measurements were carried out with 16 scans and 4 cm−1 resolution. Absorbances wererecordedat wavenumbers ranging from 400 to 4000 cm−1.

2.3.5. Mechanical properties

Instron 5869 Universal Testing Machine (Norwood, MA, USA)was used to testthe mechanical properties such as tensile strength, elongation at break and elastic modulus of the films. The specimens corresponded to the Type 5 and the test method was ASTM D638–14 standard test method for tensile properties of plastics. The films were cut using a double blade cutter. Before testing, the thickness of the filmstrip and width in the thinner dimension of the filmstrip were measured using micrometer. The filmstrips were clamped in the testing machine which operated at an initial gap separation of 30mm with cross head speed of 10 mm/min. The tensile strength, elongation at break, and elastic modulus were determined by the computer software. Five measurements were performed for each sample.

2.3.6. Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA)

Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) of samples was performed by using a TGA instrument (PerkinElmer Ltd., Waltham, USA). The film samples, 10 – 15 mg, were heated from 25 °C to 700 °C at a heating rate of 10 °C/min under a nitrogen atmosphere with flow rate of 20 mL/min.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Experiments were conducted in triplicate, except for mechanical propertieswherefive measurements were used. For each sample theresultsare presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). The software SPSS 20 was used for the determination of statically significance between sample comparisons. Differences were considered at significant level of 95% and (p-value of < 0.05).

3. Result and Discussion

Films were produced using asolution casting method for 30% or40% (w/w) of plasticizer to dry starch ration. Four different kinds of plasticizers (glycerol, 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium acetate, sorbitol,andtriethylene glycol) were used in this study. The prepared films were transparent, facileto peel, homogeneous, and flexible.Thefilm made from 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium acetate was qualitatively more flexible than the others. The sorbitol plasticized film had sorbitol precipitate on the film surface. Similar conditionswerereported for a film developed from pea starch using sorbitol as plasticizer [7]. Plasticizer precipitation occurs when the concentration of plasticizer is more than its compatibility limit withthe polymer.

The resultsfor film thickness, density, moisturecontent, and water solubility of prepared films are presented in Table 1. The values of film thickness were between 0.17 and 0.26 mm. All films, except the triethylene glycol plasticized film, had thicknesses which were not significantly affected by the plasticizeridentityortheir concentrations. A film made from 40% (w/w) of triethylene glycol had the highest film thickness. The density of films ranged from 0.88 to 1.21 g/cm3. In opposite to film thickness, the 40% (w/w) of triethylene glycol film had the lowest density. The films plasticized with 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium acetate or sorbitol exhibitedincreasedwater solubility with increasing concentration, butin the case of the remaining plasticizers the opposite is true.

Table 1.

Thickness, density, water solubility and moisture content of anchote starch films made from different kind and concentration of plasticizers

| Films | Thickness (mm) | Density (g/cm3) | Water Solubility (%) | Moisture Content (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| E30 | 0.17 ± 0.01a A | 1.21 ± 0.04c D | 26.70 ± 1.25f B | 8.66 ± 0.25d C |

| E40 | 0.19 ± 0.04a A | 1.20 ± 0.05c D | 32.85 ± 1.23e B | 7.40 ± 0.55d F |

| G30 | 0.18 ± 0.00b A | 1.07 ± 0.02d B | 32.57 ± 0.82a AF | 14.92 ± 1.52a B |

| G40 | 0.19 ± 0.02b A | 1.03 ± 0.00d B | 20.97 ± 4.41b B | 21.42 ± 1.25b D |

| S30 | 0.18 ± 0.02c A | 1.20 ± 0.06a D | 28.07 ± 1.82d BF | 7.45 ± 0.56f F |

| S40 | 0.19 ± 0.01c A | 1.20 ± 0.03a D | 31.34 ± 0.51d B | 7.29 ± 0.56f C |

| T30 | 0.18 ± 0.01d A | 1.06 ± 0.19b B | 34.19 ± 6.72c AF | 18.53 ± 0.75c A |

| T40 | 0.26 ± 0.02e B | 0.88 ± 0.02f A | 18.92 ± 0.60c B | 23.61 ± 1.21e D |

Data (mean ± SD), The letters E, G, S and T indicate to 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium acetate, glycerol, sorbitol and triethylene glycol, respectively. The number next to them

Different superscript letters in a column indicate that there are statistically significant differences (P < 0.05) between samples. Lower caseletters show statistically analysis for a plasticizer with different weight percentage and capital letters indicate statistically analysis between plasticizers

The 40 % (w/w) triethylene glycol film had the highest moisture content(23.61%). This observationagrees with thedensity result. Moisture content of the 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium acetate and sorbitol plasticized films was not significantly affected by plasticizers concentration difference ortype. On the other hand, films made from other plasticizers were significantly affected by type and concentration of plasticizers (Table 1).

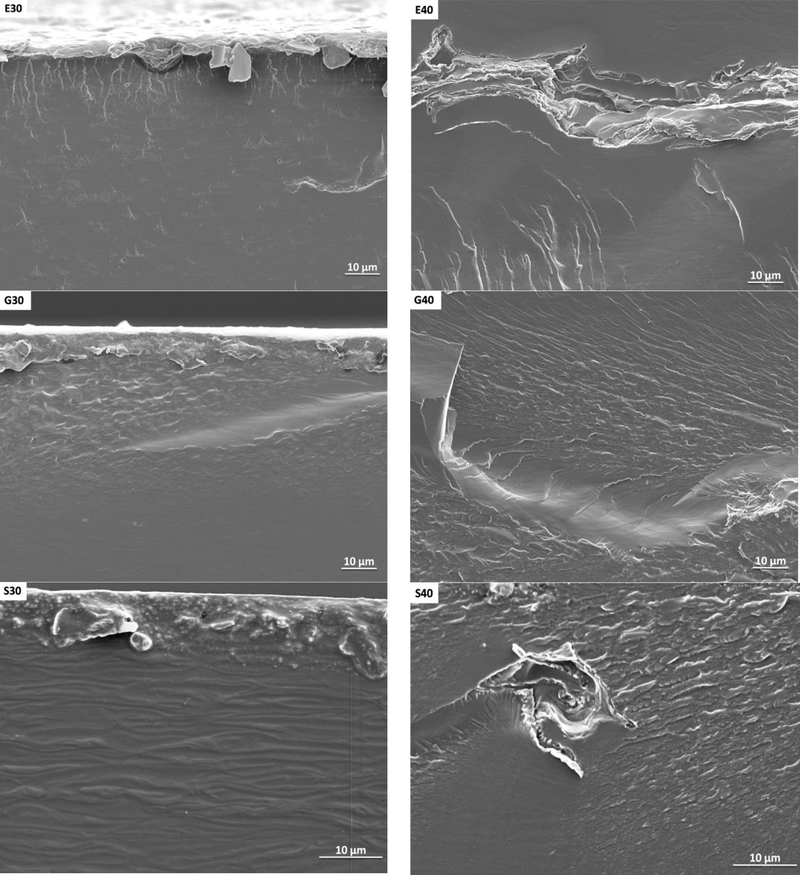

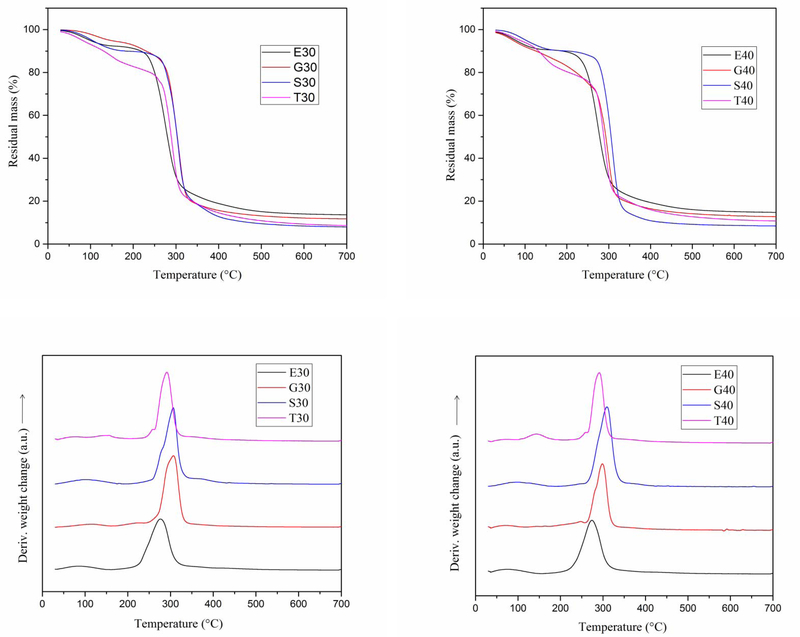

3.1. Film morphology

Morphological characteristics of the cross-section of the anchote starch filmswere observed by scanning electron microscope (SEM). The SEM images of the cross-section of films are shown in Fig. 1. In Fig. 1 E30 and E40 indicate films made from 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium acetate with 30%(w/w) and 40%(w/w), respectively. Generally, in Fig.1, the letters G, S, and T stand for glycerol, sorbitol and triethylene glycol. The numbers 30 or40 indicates their weight percentage to dry starch.Themicrographs of the fractured surface of the films developed from sorbitol show unmixed starch granules (Fig. 1S30 and S40), sorbitol plasticizer migrated to the film surface (Fig.1 S30), smooth fractured surface (Fig. 1E30, G30, and T30), and irregular fractured surface (Fig. 1E40 and G40). Regardless of the plasticizer, films with 40%(w/w)plasticizer concentration were more homogeneous than those with 30%(w/w)concentrations. Similar result have been reported for a film made from protein by solution casting using glycerol as a plasticizer with concentrations varying from 1%(w/w) to 9(w/w), where the 9%(w/w) film had homogeneous cross section [23]. The films containing 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium acetate plasticizer showed a more uniform and dense matrix than the glycerol plasticized films. This observationis a good indicator that the plasticization effect of 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium acetate is better than glycerol. This result agrees with SEM micrographs of films derived from maize starch and 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium acetate using compression moulding[12]. The film plasticized with sorbitol (Fig. 1 S30) more brittle than others; this is due to the migration of plasticizers to the surface of the film. The film made with 40% (w/w) of triethylene glycol had the roughest fractured surface.

Figure.1.

SEM images of E30-film of 30%(w/w) 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium acetate, E40-film of 40%(w/w) 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium acetate, G30-film of 30%(w/w) glycerol, G40-film of 40%(w/w) glycerol, S30-film of 30%(w/w) sorbitol, S40-film of 40%(w/w), T30-film of 30%(w/w) triethylene glycol, and T40-film of 40%(w/w) triethylene glycol)

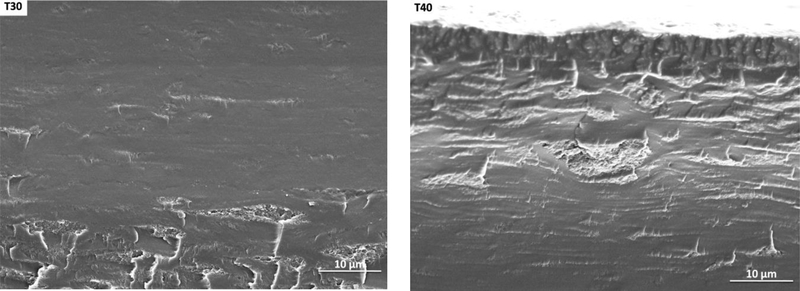

3.2. FTIR analysis

The functional groups related withanchotestarchandits films were identified using FTIR. The FTIR spectra of the films as well as anchote starch in the range from 4000 to 400 cm−1 region are shown in Fig. 2 and their characteristic absorption bands are presented in Table 3.Anchote starch FTIR spectra showed peak absorptions around the wavenumbers 573, 931, 1000, 1080, 1150, 1350, 1640, 2170, 2920 and 3310 cm-1. The peak observed around 3310 cm−1 was assigned to hydrogen bonded hydroxyl groups or the stretching vibration of O-H [24,25]. The peak at 2920 cm−1 could be attributed to stretching of C-H in CH2, while the peak at 1640 cm−1 was associated with O-H bending [26,27]. The peak at 1350 cm−1 corresponded to C-H bending [27]. The characteristic peak at 1080 and 1000 cm−1, are related to C-O bond stretching of anchote starch [28]. The D-glucopyranosyl ring vibrational modes and skeletal modes of pyranose ring were indicated at 931 and 573 cm−1, respectively[19].

Figure.2.

The FTIR spectra of AS-anchote starch, E30-film of 30%(w/w) 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium acetate, E40-film of 40%(w/w) 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium acetate, G30-film of 30%(w/w) glycerol, G40-film of 40%(w/w) glycerol, S30-film of 30%(w/w) sorbitol, S40-film of 40%(w/w), T30-film of 30%(w/w) triethylene glycol, and T40-film of 40%(w/w) triethylene glycol)

Table 3.

Effects of plasticizers on mechanical properties of anchote starch films

| Films | Tensile Strength (MPa) | Elongation at Break (%) | Modulus of (MPa) |

|---|---|---|---|

| E30 | 6.18 ± 0.65 | 49.10 ± 7.76 | 105.00 ± 32.66 |

| E40 | 4.19 ± 0.67 | 42.83 ± 9.44 | 50.20 ± 13.50 |

| G30 | 6.45 ± 1.19 | 34.26 ± 12.42 | 341 ± 68.00 |

| G40 | 6.35 ± 0.55 | 48.95 ± 4.22 | 133 ± 29.00 |

| S30 | - | - | - |

| S40 | 15.30 ± 3.91 | 25.43 ± 8.90 | 1200 ± 260.00 |

| T30 | 8.53 ± 1.25 | 17.40 ± 1.94 | 727 ± 117.04 |

| T40 | 7.01 ± 0.57 | 38.71 ± 5.70 | 447 ± 29.41 |

Data (mean ± SD), The letters E, G, S and T indicate to 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium acetate, glycerol, sorbitol and triethylene glycol, respectively. The number next to them indicates the percentage (w/w) of plasticizer to dry starch ration

The film samples, regardless of plasticizers type and concentration, showed similar characteristic absorption bands of anchote starch (Table 2). Regardless of concentration, 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium acetate, glycerol, and sorbitol plasticized films for anchote starch exhibited reduced signals at 3310 cm−1 to 3290 cm−1indicatingtheyformed stronger bond than the triethylene glycol plasticized film. This observation is attributed to hydrogen bonded hydroxyl group stretch of anchote starch, plasticizer and water [27,29]. Films plasticized with glycerol and sorbitol had higher intensity at 3290 cm-1. This result is related with an increase in hydroxyl group content due to the nature of the plasticizer.

Table 2.

FTIR absorption band of anchote starch and its films

| Samples | Wavenumber (cm−1) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AS | 3310 | 2920 | 1640 | 1350 | 1150 | 1080 | 1000 | 931 | 573 |

| E30 | 3290 | 3150 | 1570 | 1400 | 1150 | 1080 | 1000 | 930 | 575 |

| E40 | 3290 | 3150 | 1560 | 1400 | 1150 | 1080 | 1000 | 930 | 573 |

| G30 | 3290 | 2920 | 1640 | 1340 | 1150 | 1080 | 997 | 926 | 571 |

| G40 | 3290 | 2925 | 1650 | 1350 | 1150 | 1080 | 997 | 926 | 571 |

| S30 | 3290 | 2930 | 1640 | 1350 | 1150 | 1080 | 997 | 933 | 575 |

| S40 | 3290 | 2930 | 1645 | 1340 | 1150 | 1080 | 997 | 931 | 575 |

| T30 | 3310 | 2930 | 1650 | 1350 | - | - | 997 | 933 | 575 |

| T40 | 3330 | 2925 | 1650 | 1350 | - | - | 997 | 931 | 573 |

AS stands for anchote starch. The letters E, G, S and T indicate to 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium acetate, glycerol, sorbitol and triethylene glycol, respectively. The number next to them indicates the percentage (w/w) of plasticizer to dry starch ration

In conclusion, films plasticized with 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium acetate exhibited peaks at 3150, 1400 and 1000 cm−1 that were higherintensitywhen compare to other film peaks. tindicates that 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium acetate plasticized films have decreased molecular order, resulting in less hydrogen bonding [24]and a more elastic nature.

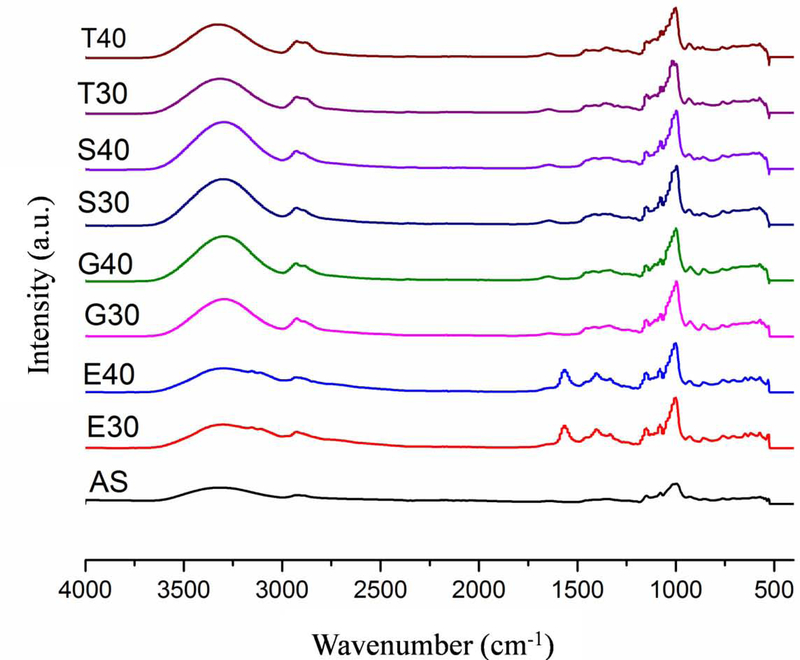

3.3. Thermal Properties

Thermal properties of the anchote starch films were investigated by thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) and derivative of thermogravimetric analysis (DTG). TGA curves of the starch films commonly had three stages of thermal degradation: the first is related with evaporation of free water, plasticizer and molecules with low molecular weight, the second is starch rich phase, there is some plasticizers, decomposition, and the last is oxidation of the partially decomposed starch[5,30]. The TGA and DTG curves of anchote films are shown in Fig 3. Thesedatarevealthat films made from 30% (w/w) of 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium acetate and sorbitol had comparable weight loss in the temperature range of 30 to 250 °C. In the same temperature range, triethylene glycol plasticized film had the highest weight losswhilethe glycerol plasticized film is the most thermally stable film. On the other hand, films made from 40% (w/w) plasticizer concentration show slight differences in their weight loss in the temperature range of 30 to 150 °C. The film plasticized using 40% (w/w) of sorbitol showed the highest thermal stability in the temperature range of 30 to 325 °C. Generally, films consistingof30% (w/w) plasticizer concentrations exhibited higher thermal stability with respect to films plasticized with 40% (w/w) concentration. Particular, films made from 40% (w/w) of triethylene glycol and glycerol showed more than 20% moisture content. Their high weight loss at lower temperature related with their high moisture content.

Figure.3.

TGA and DTGA curves for anchote starch films E30-film of 30%(w/w) 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium acetate, E40-film of 40%(w/w) 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium acetate, G30-film of 30%(w/w) glycerol, G40-film of 40%(w/w) glycerol, S30-film of 30%(w/w) sorbitol, S40-film of 40%(w/w), T30-film of 30%(w/w) triethylene glycol, and T40-film of 40%(w/w) triethylene glycol,

The DTG curves are shown in Fig. 3. The small peaks in the temperature range of 30 to 150 °C correspond withthe evaporation of water.The second majorpeak is at maximum degradation temperature which was allocated for the degradation of the starch rich phase[31]. For different plasticizers; there is slight variation in the degradation temperature of starch rich phase. Regardless of plasticizer concentration,filmsplasticized with sorbitol had the highest value for degradation temperature of starch rich phase whereas 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium acetate plasticized films had the lowest value. These differences depend on the boiling point difference of plasticizers and their interaction formed with starch molecules[24].

3.4. Mechanical properties

The results from tensile strength, elongation at break, and modulus of elasticity of anchote starch films are reportedin Table 3. A film plasticized with 30% (w/w) of sorbitol was not analyzed for mechanical properties. This filmwas very rigid and brittle when compared to other films, inhibitinganalysis. Regardless of the plasticizer type, increasing plasticizer concentration resulted in adecrease in tensile strength and modulus of elasticity. The same trends were reported for thermoplastic starch developed from different starch sources [2,14]. The tensile strength of the films provides insight into their crystallinity. It has been reported that the crystallinity of thermoplastic starch film was inversely related with plasticizer concentration [32].

Films made from sorbitol had the highest tensile strength. Its value is approximately 2 times the tensile strength of triethylene glycol plasticized film, 2.5 times glycerol plasticized film tensile strength, and 3 times tensile strength of film made from 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium acetate (Table 3). This result is due to greater number of hydroxyl groups in sorbitol resulting in stronger interactions with the polymeric starch chains [32]. 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium acetate plasticized films had the highest elongation at break compared to other films, indicating that 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium acetatewas an effective plasticizer. This result is in accord withthe homogeneous fracture surface observed for 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium acetate plasticized film under SEM.

4. Conclusions

Anchote starch films with various plasticizers were produced using a solution casting method and investigated for their morphological, thermal, and mechanical properties. The films plasticized with 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium acetate showed higher flexibility than films developed by using polyols (glycerol, sorbitol, and triethylene glycol). The thickness of films was not significantly affected by the plasticizer type and concentration, except the film prepared by using 40%(w/w) of triethylene glycol. For all plasticizers type, films were made by 40%(w/w) plasticizer concentration had more homogenous microstructure than 30% (w/w). All films showed similar characteristic absorption bands of anchote starch. The 40% (w/w) sorbitol film had the highest tensile strength and modulus of elasticity which we attribute to the high hydroxyl group content and its molecular structure. Regardless of plasticizers type, increasing plasticizer concentration resulted in adecrease in tensile strength and modulus of elasticity. This observation resulted from the inverse relationship of film crystallinity and plasticizer concentration. Films made from glycerol and sorbitol had high degradation temperatures. In sum, these results indicate that anchote film properties are a function of both plasticizer concentration and type. Furthermore, the results show that anchote starch is a potential new starch source for the production of biodegradable films which can be used for different applications, such as packaging films, trash bags, as well as shopping bagsto replace conventional plastic materials.

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by Addis Ababa University, Ethiopia, Colorado State University, and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health (R35GM119702). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].Mali S, Sakanaka LS, Yamashita F, and Grossmann MVE, Water sorption and mechanical properties of cassava starch films and their relation to plasticizing effect, Carbohydr. Polym. 60 (2005) 283–289. 10.1016/j.carbpol.2005.01.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Averous L and Boquillon N, Biocomposites based on plasticized starch : thermal and mechanical behaviours, Carbohydr. Polym. 56 (2004) 111–122. 10.1016/j.carbpol.2003.11.015 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Galdeano MC, Mali S, Grossmann MVE, Yamashita F, and García MA, Effects of plasticizers on the properties of oat starch films, Mater. Sci. Eng. C 29 (2009) 532–538. 10.1016/j.msec.2008.09.034 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Ivanič F, Kováčová M, and Chodák I, The effect of plasticizer selection on properties of blends poly(butylene adipate-co-terephthalate) with thermoplastic starch, Eur. Polym. J 116 (2019) 99–105. 10.1016/j.eurpolymj.2019.03.042 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Cyras VP, Manfredi LB, Ton-That M-T, and Vazquez A, Physical and mechanical properties of thermoplastic starch / montmorillonite nanocomposite films, Carbohydr. Polym. 73 (2008) 55–63. 10.1016/j.carbpol.2007.11.014 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Malmir S, Montero B, Rico M, Barral L, Bouza R, and Farrag Y, Effects of poly ( 3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyvalerate ) microparticles on morphological, mechanical, thermal, and barrier properties in thermoplastic potato starch films, Carbohydr. Polym. 194 (2018) 357–364. 10.1016/j.carbpol.2018.04.056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Zhang Y and Han JH, Mechanical and Thermal Characteristics of Pea Starch Films Plasticized with Monosaccharides and Polyols, J. Food Sci. 71 (2006) E109–E118. 10.1111/j.1365-2621.2006.tb08891.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Bergo P and Sobral PJA, Effects of plasticizer on physical properties of pigskin gelatin films, Food Hydrocoll. 21 (2007) 1285–1289. 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2006.09.014 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Talja RA, Hele H, Roos H, and Jouppila K, Effect of various polyols and polyol contents on physical and mechanical properties of potato starch-based films, Carbohydr. Polym. 67 (2007) 288–295. 10.1016/j.carbpol.2006.05.019 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Suyatma NE, Tighzert L, Copinet A, and Coma V, Effects of hydrophilic plasticizers on mechanical, thermal, and surface properties of chitosan films, J. Agric. Food Chem. 53 (2005) 3950–3957. 10.1021/jf048790+ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Müller CMO, Yamashita F, and Laurindo JB, Evaluation of the effects of glycerol and sorbitol concentration and water activity on the water barrier properties of cassava starch films through a solubility approach, Carbohydr. Polym. 72 (2008) 82–87. 10.1016/j.carbpol.2007.07.026 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Xie F et al. , Characteristics of starch-based films plasticised by glycerol and by the ionic liquid 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium acetate : A comparative study, Carbohydr. Polym. 111 (2014) 841–848. 10.1016/j.carbpol.2014.05.058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Felisberto MHF, Beraldo AL, Costa MS, Boas FV, Franco CML, and Clerici MTPS, Physicochemical and structural properties of starch from young bamboo culm of Bambusa tuldoides, Food Hydrocoll. 87 (2019) 101–107. 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2018.07.032 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Wang J, Cheng F, and Zhu P, Structure and properties of urea-plasticized starch films with different urea contents, Carbohydr. Polym. 101 (2014) 1109–1115. 10.1016/j.carbpol.2013.10.050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Maniglia BC, Lima DC, Matta Junior MD, Le-Bail P, Le-Bail A, and Augusto PED, Hydrogels based on ozonated cassava starch: Effect of ozone processing and gelatinization conditions on enhancing 3D-printing applications, Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 138 (2019) 1087–1097. 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2019.07.124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Zabot GL et al. , Physicochemical, morphological, thermal and pasting properties of a novel native starch obtained from annatto seeds, Food Hydrocoll. 89 (2019) 321–329. 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2018.10.041 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Zhu F, Recent advances in modifications and applications of sago starch, Food Hydrocoll. 96 (2019) 412–423. 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2019.05.035 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Abera G, Woldeyes B, Dessalegn H, and Miyake GM, Comparison of physicochemical properties of indigenous Ethiopian tuber crop ( Coccinia abyssinica ) starch with commercially available potato and wheat starches, Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 140 (2019) 43–48. 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2019.08.118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Sit N, Misra S, and Deka SC, Physicochemical, functional, textural and colour characteristics of starches isolated from four taro cultivars of North-East India, Starch/Stärke. 65 (2013) 1011–1021. 10.1002/star.201300033 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Carolina A, Solano V, Rojas C, and Gante D, Development of biodegradable films based on blue corn flour with potential applications in food packaging . Effects of plasticizers on mechanical, thermal, and microstructural properties of flour films, J. Cereal Sci. 60 (2014) 60–66. 10.1016/j.jcs.2014.01.015 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Maria F, Andrade-mahecha MM, José P, and Cecilia F, Optimization of process conditions for the production of films based on the flour from plantain bananas (Musa paradisiaca), LWT - Food Sci. Technol. 52 (2013) 1–11. 10.1016/j.lwt.2013.01.011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Reddy JP and Rhim J, Characterization of bionanocomposite films prepared with agar and paper-mulberry pulp nanocellulose, Carbohydr. Polym. 110 (2014) 480–488. 10.1016/j.carbpol.2014.04.056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Martelli M, Gandolfo C, and Jose P, Influence of the glycerol concentration on some physical properties of feather keratin films, Food Hydrocoll. 20 (2006) 975–982. 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2005.11.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Bilal M, Niazi K, and Broekhuis AA, Surface photo-crosslinking of plasticized thermoplastic starch films, Eur. Polym. J. 64 (2015) 229–243. 10.1016/j.eurpolymj.2015.01.027 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Mamaye M, Kiflie Z, Yimam A, and Jabasingh SA, Valorization of Ethiopian Sugarcane Bagasse to Assess its Suitability for Pulp and Paper Production, Sugar Tech. 21 (2019) 1–8. 10.1007/s12355-019-00724-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Khanoonkon N, Yoksan R, and Ogale AA, Morphological characteristics of stearic acid-grafted starch-compatibilized linear low density polyethylene / thermoplastic starch blown film, Eur. Polym. J. 76 (2016) 266–277. 10.1016/j.eurpolymj.2016.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Merino D, Mansilla AY, Gutiérrez TJ, Casalongué CA, and Alvarez VA, Chitosan coated-phosphorylated starch films : Water interaction, transparency and antibacterial properties, React. Funct. Polym. 131 (2018) 445–453. 10.1016/j.reactfunctpolym.2018.08.012 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Moreno O, Cárdenas J, Atarés L, and Chiralt A, Influence of starch oxidation on the functionality of starch-gelatin based active films, Carbohydr. Polym. 178 (2017) 147–158. 10.1016/j.carbpol.2017.08.128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Zullo R and Iannace S, The effects of different starch sources and plasticizers on film blowing of thermoplastic starch : Correlation among process, elongational properties and macromolecular structure, Carbohydr. Polym. 77 (2009) 376–383. 10.1016/j.carbpol.2009.01.007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Herniou C, Mendieta JR, and Gutiérrez TJ, Characterization of biodegradable / non-compostable fi lms made from cellulose acetate / corn starch blends processed under reactive extrusion conditions, Food Hydrocoll 89 (2019) 67–79. 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2018.10.024 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Salaberria AM, Diaz RH, Labidi J, and Fernandes SCM, Role of chitin nanocrystals and nano fi bers on physical, mechanical and functional properties in thermoplastic starch films, Food Hydrocoll. 46 (2015) 93–102. 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2014.12.016 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [32].García MA, Martino MN, and Zaritzky NE, Microstructural Characterization of Plasticized Starch-Based Films, Starch/Stärke. 52 (2000) 118–124. [DOI] [Google Scholar]