Abstract

Background

Beta (β) blockers are indicated for use in coronary artery disease (CAD). However, optimal therapy for people with CAD accompanied by intermittent claudication has been controversial because of the presumed peripheral haemodynamic consequences of beta blockers, leading to worsening symptoms of intermittent claudication. This is an update of a review first published in 2008.

Objectives

To quantify the potential harmful effects of beta blockers on maximum walking distance, claudication distance, calf blood flow, calf vascular resistance and skin temperature when used in patients with peripheral arterial disease (PAD).

Search methods

For this update, the Cochrane Peripheral Vascular Diseases Group Trials Search Co‐ordinator searched the Specialised Register (last searched March 2013) and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL, The Cochrane Library, 2013, Issue 2).

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) evaluating the role of both selective (β1) and non‐selective (β1 and β2) beta blockers compared with placebo. We excluded trials that compared different types of beta blockers.

Data collection and analysis

Primary outcome measures were claudication distance in metres, time to claudication in minutes and maximum walking distance in metres and minutes (as assessed by treadmill).

Secondary outcome measures included calf blood flow (mL/100 mL/min), calf vascular resistance and skin temperature (ºC).

Main results

We included six RCTs that fulfilled the above criteria, with a total of 119 participants. The beta blockers studied were atenolol, propranolol, pindolol and metoprolol. All trials were of poor quality with the drugs administered over a short time (10 days to two months). None of the primary outcomes were reported by more than one study. Similarly, secondary outcome measures, with the exception of vascular resistance (as reported by three studies), were reported, each by only one study. Pooling of such results was deemed inappropriate. None of the trials showed a statistically significant worsening effect of beta blockers on time to claudication, claudication distance and maximal walking distance as measured on a treadmill, nor on calf blood flow, calf vascular resistance and skin temperature, when compared with placebo. No reports described adverse events associated with the beta blockers studied.

Authors' conclusions

Currently, no evidence suggests that beta blockers adversely affect walking distance, calf blood flow, calf vascular resistance and skin temperature in people with intermittent claudication. However, because of the lack of large published trials, beta blockers should be used with caution, if clinically indicated.

Keywords: Humans, Adrenergic beta‐Antagonists, Adrenergic beta‐Antagonists/adverse effects, Atenolol, Atenolol/adverse effects, Intermittent Claudication, Intermittent Claudication/drug therapy, Metoprolol, Metoprolol/adverse effects, Peripheral Vascular Diseases, Peripheral Vascular Diseases/drug therapy, Pindolol, Pindolol/adverse effects, Propranolol, Propranolol/adverse effects, Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic, Regional Blood Flow, Regional Blood Flow/drug effects, Walking

Plain language summary

Beta blockers for peripheral arterial disease

Intermittent claudication, the most common symptom of atherosclerotic peripheral arterial disease, results from decreased blood flow to the legs during exercise. Beta blockers, a large group of drugs, have been shown to decrease death among people with high blood pressure and coronary artery disease and are used to treat various disorders. They reduce heart activity but can also inhibit relaxation of smooth muscle in blood vessels, bronchi and the gastrointestinal and genitourinary tracts. The non‐selective beta blockers propranolol, timolol and pindolol are effective at all beta‐adrenergic sites in the body, whereas other beta blockers, such as atenolol and metoprolol, are selective for the heart.

Optimal therapy for people with coronary artery disease or hypertension and intermittent claudication is controversial because of the presumed peripheral blood flow consequences of beta blockers, which lead to worsening of symptoms.

Currently, no evidence from randomised controlled trials suggests that beta blockers adversely affect walking distance in people with intermittent claudication, and beta blockers should be used with caution, if clinically indicated. The review authors identified six randomised controlled trials that involved a total of only 119 people with mild to moderate peripheral arterial disease. The beta blockers studied were propranolol, pindolol, atenolol and metoprolol. None of the trials showed clear worsening effects of beta blockers on time to claudication, claudication distance and maximal walking distance as measured on a treadmill, nor on calf blood flow, calf vascular resistance and skin temperature, when compared with placebo. Trial investigators reported no adverse events or issues regarding taking the beta blockers studied.

Most of the trials were over 20 years old and reported findings between 1980 and 1991. All were small and of poor quality. The drugs were administered over a short time (10 days to two months), and most of the outcome measures were reported in single studies. Additional drugs-calcium channel blockers and combined alpha and beta blockers-were given during some of the trials.

Background

Description of the condition

Intermittent claudication, the most common symptom of atherosclerotic peripheral arterial disease (Hiatt 2001), reflects decreased blood flow to the extremities during exercise (Lassila 1986). The incidence of intermittent claudication increases with advancing age, cigarette smoking, impaired glucose tolerance and hypertension (Hughson 1978). Men are twice as likely as women to be affected by intermittent claudication (Kannel 1985).

Patients with peripheral arterial disease (PAD) have increased rates of mortality due to concurrent coronary artery disease and hypertension (Criqui 1985).

Description of the intervention

Beta (β) blockers were thought to decrease all‐cause and cardiovascular mortality and were used as a first‐line medication for primary hypertension. However, recent evidence is counter‐intuitive to this and has demonstrated that beta blockers are less efficacious than placebo, thiazides or angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors in the treatment of primary hypertension (Bangalore 2007; Lavie 2009; Lindholm 2005; Wiysonge 2007; Wright 2009). Further, beta blockers are associated with a higher incidence of all‐cause and cardiovascular mortality compared with other antihypertensive medication. Furthermore, a recent Cochrane review showed that beta blockers fail to improve cardiovascular mortality even when used as a second‐line therapy for treatment of hypertension (Chen 2010). Currently, beta blockers are indicated in the treatment of angina and acute myocardial infarction and heart failure (Javed 2009; NICE 2010). In addition, they are used to treat arrhythmias (variations in the normal rhythm of the heartbeat), migraine headaches, essential tremors, thyrotoxicosis (excessive production of thyroid hormones), glaucoma, anxiety and various other disorders.

Beta blockers make up a large group of drugs, and although all are competitive inhibitors of β receptors, they may have additional pharmacodynamic properties. In addition to increasing the force and rate of myocardial contraction, β1 receptors increase conduction velocity through the atrioventricular (AV) node. Beta1 blockade, therefore, reduces heart rate, blood pressure, myocardial contractility and myocardial oxygen consumption. Beta2 receptor blockade inhibits relaxation of smooth muscle in blood vessels, bronchi and the gastrointestinal and genitourinary tracts. In addition, β2 blockade inhibits the breakdown of glycogen (the main carbohydrate storage compound) to glucose (glycogenolysis) and the formation of sugar from protein and fat in the absence of glucose or carbohydrate (gluconeogenesis). Non‐specific beta blockers such as propranolol, timolol, nadolol, and pindolol demonstrate equal affinity for both β1 and β2 receptors. Commonly used cardioselective (β1) blockers are atenolol and metoprolol.

How the intervention might work

In general, blockade of β receptors results in decreased production of intracellular cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP), with resultant blunting of the multiple metabolic and cardiovascular effects of circulating catecholamines. Beta blockers are indicated for use after myocardial infarction (MI). It has been shown that therapy initiated within 12 hours of MI decreases the rate of in‐hospital cardiovascular mortality by 13% to 15% (MIAMI trial). Beta blockers have also been indicated for use in patients with continuing or recurrent ischaemic pain, tachyarrhythmias (rapid heart rates associated with an irregularity in the normal heart rhythm) and non-ST‐elevation MI (ACCF/AHA 2012).

Optimal therapy for coronary artery disease or hypertension accompanied by intermittent claudication has been controversial because of presumed peripheral haemodynamic consequences of beta blockers that could lead to worsening of symptoms in patients with PAD (George 1974). This has been attributed to decreased cardiac output and unopposed alpha (α)‐adrenergic drive.

Why it is important to do this review

It is well known that acute lowering of blood pressure is contraindicated in critical ischaemia. However, the effect of lowering of blood pressure in people with intermittent claudication is not known. Beta blockers are contraindicated in severe PAD (BNF 2013). The aim of this review is to gather evidence for the contraindication of beta blockers in people with intermittent claudication.

Objectives

To quantify the potential harmful effects of beta blockers on maximum walking distance, claudication distance, calf blood flow, calf vascular resistance and skin temperature when used in patients with PAD.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) comparing beta blockers and placebo in participants with PAD.

Types of participants

Patients with moderate to severe PAD, with or without additional co‐morbidity (an additional disease or condition, for example, diabetes mellitus), were included. Peripheral arterial disease was defined as a typical history of intermittent claudication and reduced ankle brachial pressure index (ABPI)-less than 0.9.

Types of interventions

We included studies that used selective beta blockers (β1) and non‐selective beta blockers (β1 and β2). We excluded studies using some beta blockers with additional alpha (α) blocking properties (for example, labetalol).

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Primary outcome measures considered for this review were initial claudication distance in metres, time to claudication in minutes and maximal walking distance in metres and minutes (as assessed by treadmill).

Secondary outcomes

Secondary outcome measures included calf blood flow (mL/100 mL/min), calf vascular resistance and skin temperature (ºC). Mortality data and complications associated with the use of beta blockers, such as development of critical ischaemia, cardiovascular morbidity and mortality; all‐cause mortality; and drug withdrawal, were also recorded for participants with stable PAD.

Search methods for identification of studies

No restrictions on language of publication were applied.

Electronic searches

For this update, the Cochrane Peripheral Vascular Diseases Group Trials Search Co‐ordinator (TSC) searched the Specialised Register (last searched March 2013) and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (2013, Issue 2; part of The Cochrane Library, www.thecochranelibrary.com). See Appendix 1 for details of the search strategy used to search CENTRAL. The Specialised Register is maintained by the TSC and is constructed from weekly electronic searches of MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL and AMED and handsearching of relevant journals. The full list of the databases, journals and conference proceedings that have been searched and the search strategies used are described in the Specialised Register section of the Cochrane Peripheral Vascular Diseases Group module in The Cochrane Library (www.thecochranelibrary.com).

Searching other resources

We searched bibliographies of all identified research articles and review articles.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

All three review authors independently reviewed abstracts of potential trials involving beta blockers in PAD. We obtained full papers for those fulfilling the relevant criteria or when clarification was required. We excluded trials that compared different types of beta blockers.

Studies that met the inclusion criteria were independently selected by SCVP and DAM, and this process was overseen by ADS. No disagreements among SCVP and DAM regarding inclusion were reported; however, both could not decide on inclusion of one study, and this decision was made by ADS.

Data extraction and management

SCVP and DAM independently extracted data from the included studies using the proforma designed by the Cochrane PVD Group.

Some of the results, for example, calf blood flow (Hiatt 1985; Lepantalo 1984a; Lepantalo 1985), claudication and maximal walking distance (Roberts 1987), were presented only as graphs, hence we excluded them from the analyses.

Vascular resistance is described in arbitrary units. The review authors calculated vascular resistance by dividing mean arterial blood pressure by calf blood flow.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

All three review authors independently assessed the methodological quality of selected trials using the Cochrane 'Risk of bias' tool provided in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (version 5.1.0) (Higgins 2011). The results for each included trial are summarised in the 'Risk of bias' tables.

Measures of treatment effect

We planned to use odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence interval (CI) for dichotomous variables and mean difference (MD) with 95% CI for continuous variables.

Meta‐analyses were not performed, hence data from individual trials are discussed and presented.

Unit of analysis issues

Each participant was considered an individual unit of analysis for this review, as meta‐analyses were not performed. However, in future reviews, if new trials have been published, for cross‐over trials, when available, paired data will be considered to avoid unit of analysis error. If it becomes difficult to identify data clearly, individual participant data will be considered for meta‐analysis, but results will be presented with caution.

Dealing with missing data

Some key data were missing from some of the trials. As they were old trials, study co‐ordinators could not be contacted to obtain more information. With regards to some trials, details of standard deviation were calculated from the provided standard error and mean, as discussed by Higgins 2011.

Assessment of heterogeneity

Variability in participants, interventions and outcomes was considered in the assessment of clinical heterogeneity. As a meta‐analysis was not performed, statistical heterogeneity was not relevant.

If new trials are included in future updates of this review, when possible, we will perform statistical analysis according to the statistical guidelines for review authors put forth by the Cochrane PVD Group. We will assess the degree of heterogeneity amongst trials by using the I2 statistic according to the formula I2 = 100% × (Q ‐ degrees of freedom)/Q, where Q is the Chi2 statistic (Higgins 2011). We will present a summary statistic for each outcome using a fixed‐effect model for homogenous data and a random‐effects model for heterogenous data.

Assessment of reporting biases

The review authors intended to use funnel plots for publication bias; however, as no meta‐analysis was performed, this could not be done. All studies were carefully assessed to look for selective reporting bias. Whilst no uniformity was observed in the results presented, outcome reporting was quite varied among trials.

Data synthesis

Because data from the included studies were insufficient, meta‐analysis was not performed. If new trials are included in future updates of this review, we will present a summary statistic for each outcome using a fixed‐effect model for homogenous data and a random‐effects model for heterogenous data.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Subgroup analysis was not feasible because data were insufficient; however, such an analysis will be carried out if sufficient data are provided by future trials.

Sensitivity analysis

We planned to undertake sensitivity analyses to examine the stability of the results in relation to a number of factors, including study quality, the source of the data (published and unpublished) and participant type. Such analyses were not undertaken because sufficient data were lacking.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

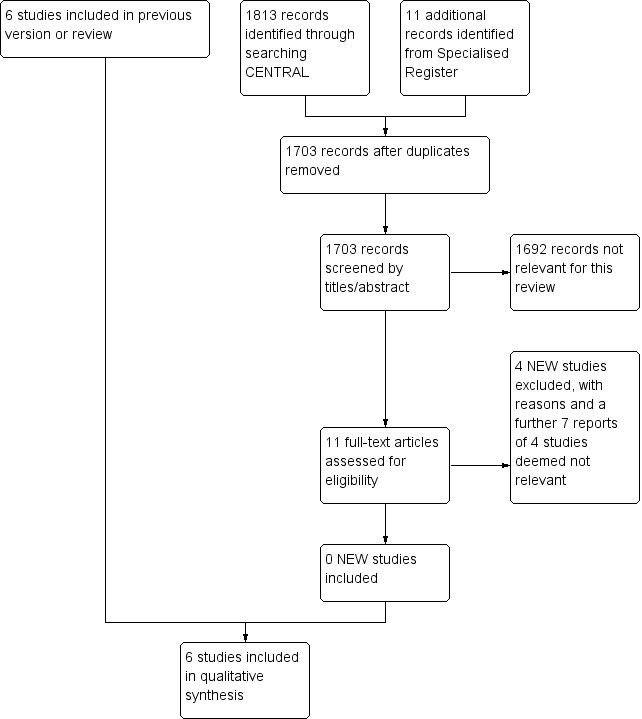

See Figure 1.

1.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

No additional studies are included in this update.

We have included six RCTs that fulfilled the inclusion criteria for this review (Clement 1980; Hiatt 1985; Lepantalo 1984a; Lepantalo 1985; Roberts 1987; Solomon 1991). Summary details of included studies are given in the Characteristics of included studies table.

Various beta blockers were used and compared with placebo in the above‐mentioned trials. Propranolol, atenolol and metoprolol were the most commonly evaluated beta blockers.

In a randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial, Clement 1980 evaluated the effects of propranolol (80 mg twice daily) and metoprolol (100 mg twice daily) on claudication and maximal walking times in participants with chronic intermittent claudication. In this cross‐over trial, 10 participants with chronic intermittent claudication were given a wash‐out period with placebo for four weeks and were subsequently randomly assigned to receive metoprolol, propranolol or placebo, each for two months.

Hiatt 1985 compared the effects of metoprolol (50 mg) and propranolol (40 mg) with those of placebo on calf blood flow and vascular resistance. In this randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial, 19 participants with chronic stable intermittent claudication received placebo in the run‐in phase for three weeks. Participants were later randomly assigned to receive either metoprolol or propranolol for two weeks. Subsequently, they were administered placebo for two weeks before the cross‐over phase. As in the earlier studies, calf blood flow was measured using venous occlusion plethysmography.

Lepantalo 1984a studied the effects of metoprolol and methyldopa on calf blood flow and vascular resistance in participants with peripheral vascular disease. In this randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial, 14 participants were given placebo in the run‐in phase for three weeks and were subsequently randomly assigned to receive metoprolol (100 to 200 mg), methyldopa (500 to 1000 mg) or placebo, each for three weeks. Calf blood flow was measured using venous occlusion plethysmography.

In another randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial, Lepantalo 1985 evaluated the effects of propranolol (80 mg), pindolol (5 mg), labetalol (200 mg), labetalol (400 mg) and placebo on hyperaemic calf blood flow, skin temperature and vascular resistance in seven participants with hypertension and chronic intermittent claudication. All drugs were administered for 10 days.

Roberts 1987 administered atenolol (100 mg), labetalol (200 mg), pindolol (5 mg), captopril (25 mg) and placebo to a total of 20 participants and studied their effects on mean blood pressure, calf blood flow, mean pain‐free walking distance and mean maximal walking distance. All participants received placebo for a month as an initial wash‐out phase. Later, they were randomly assigned to receive atenolol, labetalol, pindolol, captopril or placebo, each for one month. Calf blood flow was measured using venous occlusion plethysmography, and walking distances were assessed using a treadmill.

Solomon 1991 evaluated the effects of atenolol (50 mg), nifedipine (20 mg) and a combination of atenolol and nifedipine, as well as placebo, on skin temperature and walking distance in a total of 49 participants, who were randomly assigned after a run‐in phase with placebo. In this cross‐over trial, drugs were administered, each for four weeks. No wash‐out period preceded cross‐over of participants.

None of the primary outcomes were reported by more than one study. Similarly, secondary outcome measures, with the exception of vascular resistance (as reported by three studies), were reported, each by only one study. Pooling of such results was deemed inappropriate, hence results of individual series are presented.

Excluded studies

An additional four studies (Diehm 2011; Ehrly 1987; Espinola‐Klein 2011; van de Ven 1994) were excluded in this update, making a total of 22 excluded studies, with the reasons stated in the table Characteristics of excluded studies.

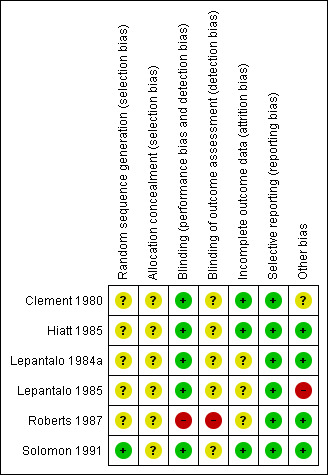

Risk of bias in included studies

Moderate to high risk of bias was seen in the included trials, as most of the methodological details, especially details on method of randomisation, could not be obtained from trial authors. Further details are provided in Figure 2 and Figure 3.

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

Details on method of randomisation was mentioned only in Roberts 1987 (randomisation codes) and Solomon 1991 (computer randomisation).

Allocation concealment for most trials was unclear because of lack of reporting. Roberts 1987 reported that the study tablets were dispensed monthly by hospital staff, but no further details were provided.

Blinding

Most trials were reported to be double‐blinded; however, in Roberts 1987, an independent observer who was aware of the randomisation codes assessed symptoms of participants at each visit.

Incomplete outcome data

Whilst Clement 1980, Hiatt 1985 and Solomon 1991 used intention‐to‐treat analysis, it was unclear whether such analysis was undertaken in the remaining trials (Lepantalo 1984a; Lepantalo 1985; Roberts 1987). These were therefore judged to be at unclear risk of bias.

Selective reporting

All trials (Clement 1980; Hiatt 1985; Lepantalo 1984a; Lepantalo 1985; Roberts 1987; Solomon 1991) reported their predetermined outcomes and therefore were judged to be at low risk of bias. Outcomes were quite varied, and the method of reporting differed between trials such that a meta‐analysis could not be performed.

Other potential sources of bias

Details regarding cross‐over were unclear in the Clement 1980 trial, hence the potential for other bias exists. In the Lepantalo 1985 trial, exclusion criteria were unclear, as were losses to follow‐up. No suggestions can be made regarding other potential sources of bias in the remaining trials (Hiatt 1985; Lepantalo 1984a; Roberts 1987; Solomon 1991).

Effects of interventions

Claudication time

One trial evaluated claudication time (Clement 1980). In this study, propranolol and metoprolol were compared with placebo. Mean claudication times were 5.20 minutes (standard deviation (SD) 2.25), 4.90 minutes (SD 2.04) and 4.53 minutes (SD 1.43) with propranolol, metoprolol and placebo, respectively.

Maximum walking time

One trial evaluated maximum walking time (Clement 1980). Propranolol and metoprolol were compared with placebo. Mean maximal walking times were 8.18 minutes (SD 2.54), 8.18 minutes (SD 2.47) and 7.75 minutes (SD 2.20) with propranolol, metoprolol and placebo, respectively.

Claudication distance

Only one trial evaluated claudication distance (Solomon 1991) and compared atenolol with placebo. Mean claudication distance was 62.6 metres for those who received atenolol versus 66.5 metres for those in the placebo group. The author reported a mean change reduction of 6% (95% CI 1% to ‐13%), which was considered to be clinically and statistically insignificant.

Maximum walking distance

Solomon 1991 evaluated maximum walking distance while comparing atenolol with placebo. Maximum walking distances with atenolol and placebo were 110.8 metres and 113.8 metres, respectively. The author reported a mean change reduction of 2% (95% CI 4% to ‐8%), which was considered to be clinically and statistically insignificant.

Calf blood flow after exercise

Roberts 1987 compared the effects of atenolol and pindolol with those of placebo on calf blood flow after exercise. Mean calf blood flow after exercise was 25.5 (SD 15.6), 20.1 (SD 10.2) and 29.9 (SD 17.8) mL/dL/min with atenolol, pindolol and placebo, respectively.

Calf vascular resistance

The effects of propranolol and pindolol versus those of placebo on vascular resistance after reactive hyperaemia were evaluated in one trial (Lepantalo 1985). Vascular resistance was 2.5 units (SD 1.2), 2.1 units (SD 1.3) and 2.1 units (SD 1.3) with propranolol, pindolol and placebo, respectively.

The effect of metoprolol on calf vascular resistance was evaluated by Lepantalo 1984a. Results showed vascular resistance to be 1.7 units (SD 0.9) with metoprolol and 1.5 units (SD 1.0) with placebo.

Hiatt 1985 also compared the effect of metoprolol on vascular resistance after exercise. Vascular resistance was 11.5 units (SD 4.7) and 11.2 units (SD 4.4) for metoprolol and placebo, respectively.

Skin temperature

The effects of propranolol and pindolol on skin temperature were evaluated in one trial (Lepantalo 1985). Mean skin temperature was 24.9°C (SD 3.8), 25.5°C (SD 4.0) and 27°C (SD 4.1) with propranolol, pindolol and placebo, respectively.

Adverse events

For all of the trials that we reviewed, no reports described adverse events related to the use of beta blockers, including critical ischaemia, cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. These trials described no issues regarding participant compliance with medication.

Discussion

Summary of main results

This systematic review identified six randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, cross‐over trials with a total of 119 participants. Most were small trials that recruited between 10 and 20 participants, and the largest study enrolled 49 participants (Solomon 1991).

None of the trials showed statistically significant worsening effects for beta blockers on the primary or secondary outcomes in participants with claudication. All trials were of poor quality, with the drugs administered over a short time (10 days to two months).

Investigators in the trial by Clement (Clement 1980) when using propranolol did not demonstrate a statistically significant decrease in claudication time or maximum walking time. This was a small trial that included only 10 participants. Details and data regarding the cross‐over phase were unclear.

Lepantalo (Lepantalo 1984a) studied the effects of metoprolol on calf blood flow and vascular resistance. Results showed no deleterious effects in the metoprolol group. In this cross‐over trial, participants were also randomly assigned to receive methyldopa, further confounding study results.

In another study, Lepantalo (Lepantalo 1985) randomly assigned a small number of participants to receive placebo, propranolol, pindolol and different strengths of labetalol (200 mg, 400 mg). The results, as described previously, showed no statistically significant worsening effects on the studied outcome measures. This small group of participants lacked proper randomisation and the cross‐over phase was unclear, raising additional questions about the validity of study conclusions.

The overall effects of atenolol on claudication and maximal walking distances could not be estimated because sufficient data were lacking. In the trial by Solomon (Solomon 1991), nifedipine (a calcium channel blocker) was also used in one of the drug groups, but no wash‐out period was provided before the cross‐over phase. This would have affected the outcome measures, which may not truly represent the effects of each individual drug.

A few limitations of this review are worth noting. Most of the trials were over 20 years old, and none of the reports supplied power calculations or a valid method of randomisation. Most important, no consistency of the inclusion criteria was noted between trials, and most of the included participants suffered from mild or moderate peripheral vascular disease. The duration of the course of beta blockers and of the cross‐over phases varied between trials, and no wash‐out periods were provided in some trials. In other trials, calcium channel blockers and combined alpha and beta blockers were used. Furthermore, primary outcome measures were available in only two trials, and complete outcome data were lacking in one of them. Finally, data were insufficient to pool individual results, hence individual data are presented. In conclusion, despite the inclusion of six RCTs, evidence supporting or refuting the use of beta blockers in peripheral arterial disease remains elusive.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

This review addressed whether evidence is available to suggest that beta blockers are harmful for patients with intermittent claudication. Not all outcome measures were available from all studies, and in some cases, trials reported incomplete data. These trials were very old, were not of good quality and consisted of only a minimal number of participants. The evidence, therefore, is not contemporary; however, no major adverse events resulting from the use of beta blockers were reported, which suggests that beta blockers may be used if required in patients with intermittent claudication. A cautious approach should be taken in patients with critical ischaemia.

All included trials were over 20 years old. Today, patients are increasingly aware of their health conditions, the importance of addressing their lifestyles and their co‐morbidities are well managed. It is therefore possible that outcomes may vary considerably if the trials included in this review were to be repeated now. Therefore, the results of these trials should be interpreted with caution.

Quality of the evidence

The trials included in this review were not of high quality, and most failed to mention the randomisation technique or allocation concealment process used or losses to follow‐up. Further, data were not clearly presented, and some of the outcomes of this review were not available in the included studies.

Potential biases in the review process

Two review authors (SCVP, DAM) independently assessed the articles for inclusion and exclusion criteria, thereby minimising the risk of any potential selection bias of articles. All data were extracted by using the proforma developed by the Cochrane PVD group. Data analysis was performed by two review authors (SCVP, DAM), and the senior review author (ADS) independently checked all results before final assessment and drafting of the manuscript.

Some results, for example, calf blood flow (Hiatt 1985; Lepantalo 1984a; Lepantalo 1985), claudication distance and maximal walking distance (Roberts 1987), were presented only as graphs, hence we excluded them from the analyses, as it was not possible to derive data suitable for inclusion.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

Miyajima et al (Miyajima 2004) conducted a review of RCTs that compared the effects of beta blockers versus placebo on intermittent claudication. Their review was slightly different in that they collated different beta blockers (although of the same type) versus placebo and found significant worsening of claudication distance with beta blockers. We do not agree with this method, as different drugs have different pharmacological properties. For example, pindolol and acebutolol have some intrinsic sympathomimetic activity as well (BNF 2013). Miyajima 2004 identified this and performed a subanalysis of beta blockers with and without intrinsic sympathomimetic activities and found no significant difference in walking distance. We think this grouping is also not appropriate because in the group without sympathomimetic activity, the authors included labetalol, which has an additional action of lowering peripheral vascular resistance that is not provided by the rest (BNF 2013). Although we disagree with the methods used by these review authors, their overall results suggested no significant effects of beta blockers on claudication time.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

The results of this systematic review have provided no strong evidence for or against the use of beta blockers in people with peripheral arterial disease. This has practice implications, as beta blockers play a significant role in averting major cardiovascular and perioperative complications. Thus the current advice that beta blockers should be used with caution in people with significant peripheral arterial disease still stands.

Implications for research.

Currently, no evidence suggests that beta blockers adversely affect walking distance in people with intermittent claudication. However, no large published trials are available. Beta blockers should be used with caution, if clinically indicated, especially in cases of critical ischaemia for which acute lowering of blood pressure is contraindicated. The authors recommend that high‐quality, randomised trials be conducted to evaluate the role of beta blockers in patients with mild, moderate and severe peripheral vascular disease.

Feedback

Comment by Dr Aaron Tejani, 1 February 2010

Summary

Paravastu et al have provided insight into an important topic, and I thank them for their work. I do however want to clarify some statements made regarding what is known about beta blockers. The authors state that "beta blockers have been shown to reduce mortality in people with hypertension and coronary artery disease." The first part of this statement is not correct. Wiysonge 2009 found that for hypertension, "the risk of all‐cause mortality was not different between first‐line beta‐blockers and placebo (RR 0.99, 95% CI 0.88 to 1.11, I2 = 0%), diuretics or RAS inhibitors, but was higher for beta blockers compared with CCBs (RR 1.07, 95% CI 1.00 to 1.14, I2 = 2.2%; ARI = 0.5%, NNH = 200)." In addition, Wright 2009 found that beta blockers, when used first line for hypertension, "reduced stroke (RR 0.83, 95% CI 0.72, 0.97) and CVS (RR 0.89, 95% CI 0.81, 0.98) but not CHD (RR 0.90, 95% CI 0.78, 1.03) or mortality (RR 0.96, 95% CI 0.86, 1.07)." The second part of the authors' statement mentioned above is also not entirely reflective of evidence for beta blockers. Beta blockers have not been shown to reduce mortality in ALL coronary artery disease patients. It is important to clarify that beta blockers have been shown to reduce mortality only in the setting of an acute myocardial infarction (Freemantle 1999, CAPRICORN 2001). Finally, it was not mentioned that beta blockers have been shown to reduce mortality in patients with heart failure.(Brophy 2001). Aaron M Tejani Cochrane Hypertension Review Group Brophy JM, Joesph L, Rouleau JL. Beta blockers in congestive heart failure: a bayesian meta analysis. Ann Intern Med 2001;134:550‐560. CAPRICORN Investigators. Effect of carvedilol on outcome after myocardial infarction in patients with left ventricular dysfunction: the CAPRICORN randomized trial. Lancet 2001;357:1385‐1390. Fremantle N, Cleland J, Young P, et al. Beta blockade after myocardial infarction: systematic review and meta regression analysis. BMJ 1999;318:1730‐1737. Wiysonge CSU, Bradley HA, Mayosi BM, Maroney RT, Mbewu A, Opie L, et al. Beta‐blockers for hypertension. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2007, Issue 1. Art. No.: CD002003. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD002003.pub2. Wright JM, Musini VM. First‐line drugs for hypertension. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2009, Issue 3. Art. No.: CD001841. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD001841.pub2.

Reply

On behalf of all authors, I would like to thank Aaron Tejani for highlighting the above issues. We have looked at the latest evidence on the role of beta blocker use in hypertension and have incorporated the necessary changes in the manuscript.

Contributors

Feedback: Aaron M Tejani, Cochrane Hypertension Review Group

Reply: Mr Sharath Paravastu, Contact author of the review, Cochrane Peripheral Vascular Diseases Group

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 2 August 2013 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | Searches rerun, no new studies included, four new studies excluded. Risk of bias tables completed and methods and abstract updated to reflect current Cochrane standards. Conclusions not changed. |

| 2 August 2013 | New search has been performed | Searches rerun, no new studies included, four new studies excluded. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 4, 2005 Review first published: Issue 4, 2008

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 16 February 2010 | Feedback has been incorporated | Feedback and review author's reply added to review. |

| 3 July 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

Acknowledgements

The authors sincerely thank Mrs Heather Maxwell and the editors of the Cochrane Peripheral Vascular Diseases Review Group for their support, and Dr Janet Wale of the Cochrane Consumer Network for providing a plain language summary. The authors would also like to acknowledge the efforts of the staff at The John Spalding Library at Wrexham Maelor Hospital in obtaining the papers for review.

Appendices

Appendix 1. CENTRAL search strategy

| #1 | MeSH descriptor: [Arteriosclerosis] this term only | 893 |

| #2 | MeSH descriptor: [Arteriolosclerosis] this term only | 0 |

| #3 | MeSH descriptor: [Arteriosclerosis Obliterans] this term only | 71 |

| #4 | MeSH descriptor: [Atherosclerosis] this term only | 382 |

| #5 | MeSH descriptor: [Arterial Occlusive Diseases] this term only | 755 |

| #6 | MeSH descriptor: [Intermittent Claudication] this term only | 711 |

| #7 | MeSH descriptor: [Ischemia] this term only | 753 |

| #8 | MeSH descriptor: [Peripheral Vascular Diseases] explode all trees | 2150 |

| #9 | MeSH descriptor: [Vascular Diseases] this term only | 381 |

| #10 | MeSH descriptor: [Leg] explode all trees and with qualifiers: [Blood supply ‐ BS] | 1075 |

| #11 | MeSH descriptor: [Femoral Artery] explode all trees | 720 |

| #12 | MeSH descriptor: [Popliteal Artery] explode all trees | 250 |

| #13 | MeSH descriptor: [Iliac Artery] explode all trees | 151 |

| #14 | MeSH descriptor: [Tibial Arteries] explode all trees | 29 |

| #15 | (atherosclero* or arteriosclero* or PVD or PAOD or PAD) | 17195 |

| #16 | (arter*) near (*occlus* or steno* or obstuct* or lesio* or block* or obliter*) | 4872 |

| #17 | (vascular) near (*occlus* or steno* or obstuct* or lesio* or block* or obliter*) | 1378 |

| #18 | (vein*) near (*occlus* or steno* or obstuct* or lesio* or block* or obliter*) | 713 |

| #19 | (veno*) near (*occlus* or steno* or obstuct* or lesio* or block* or obliter*) | 976 |

| #20 | (peripher*) near (*occlus* or steno* or obstuct* or lesio* or block* or obliter*) | 1358 |

| #21 | peripheral near/3 dis* | 3243 |

| #22 | arteriopathic | 10 |

| #23 | (claudic* or hinken*) | 1436 |

| #24 | (isch* or CLI) | 16827 |

| #25 | dysvascular* | 14 |

| #26 | leg near/4 (obstruct* or occlus* or steno* or block* or obliter*) | 176 |

| #27 | limb near/4 (obstruct* or occlus* or steno* or block* or obliter*) | 228 |

| #28 | (lower near/3 extrem*) near/4 (obstruct* or occlus* or steno* or block* or obliter*) | 137 |

| #29 | (aort* or iliac or femoral or popliteal or femoro* or fempop* or crural) near/3 (obstruct* or occlus*) | 326 |

| #30 | #1 or #2 or #3 or #4 or #5 or #6 or #7 or #8 or #9 or #10 or #11 or #12 or #13 or #14 or #15 or #16 or #17 or #18 or #19 or #20 or #21 or #22 or #23 or #24 or #25 or #26 or #27 or #28 or #29 | 39632 |

| #31 | MeSH descriptor: [Adrenergic beta‐Antagonists] explode all trees | 3978 |

| #32 | (betablocker* or beta‐blocker*):ti,ab,kw (Word variations have been searched) | 4040 |

| #33 | (adrenergic near/3 (antagonist* or block*)):ti,ab,kw (Word variations have been searched) | 6714 |

| #34 | (beta* near/3 block*):ti,ab,kw (Word variations have been searched) | 7168 |

| #35 | acebutolol or atenolol or Tenormin or alprenolol:ti,ab,kw (Word variations have been searched) | 3067 |

| #36 | betaxolol or bisoprolol or bupranolol:ti,ab,kw (Word variations have been searched) | 832 |

| #37 | carvedilol or Coreg or carteolol or celiprolol:ti,ab,kw (Word variations have been searched) | 976 |

| #38 | esmolol or labetalol or Normodyne or Trandate:ti,ab,kw (Word variations have been searched) | 834 |

| #39 | metoprolol or nadolol or nebivolol:ti,ab,kw (Word variations have been searched) | 2644 |

| #40 | oxprenolol or penbutolol or pindolol:ti,ab,kw (Word variations have been searched) | 1240 |

| #41 | Visken or practolol or propranolol or Inderal:ti,ab,kw (Word variations have been searched) | 4255 |

| #42 | sotalol or timolol:ti,ab,kw (Word variations have been searched) | 2051 |

| #43 | #31 or #32 or #33 or #34 or #35 or #36 or #37 or #38 or #39 or #40 or #41 or #42 | 16792 |

| #44 | #30 and #43 in Trials | 1813 |

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Clement 1980.

| Methods | Study design: randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, cross‐over trial Method of randomisation: not stated Concealment of allocation: not stated Exclusions post‐randomisation: none Losses to follow‐up: none Intention‐to‐treat analysis: yes | |

| Participants | Country: Belgium Setting: hospital Number: 10 Age: 62 ± 2 years (mean ± SEM) Sex: male Inclusion criteria: chronic intermittent claudication Exclusion criteria: not stated | |

| Interventions | Treatment: propranolol (80 mg bid); metoprolol (100 mg bid) Control: placebo Duration: All participants entered a run‐in, wash‐out period of 4 weeks, followed by propranolol, metoprolol or placebo, each for 2 months | |

| Outcomes | Claudication time and maximum walking time | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Randomisation method not stated |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not stated |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Reports 'double‐blind', no further information provided |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Analysis was intention‐to‐treat, no losses to follow‐up |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | No evidence of selective reporting |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Details on cross‐over inadequately provided |

Hiatt 1985.

| Methods | Study design: randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, cross‐over trial Method of randomisation: not stated Concealment of allocation: not stated Exclusions post‐randomisation: none Losses to follow‐up: none Intention‐to‐treat analysis: yes | |

| Participants | Country: USA Setting: hospital Number: 19 Age: sequence 1, 57 ± 3 years (mean ± SEM); sequence 2, 58 ± 3 years (mean ± SEM) Sex: male 16; female 3 Inclusion criteria: diagnosis of chronic stable intermittent claudication confirmed by previous non‐invasive testing Exclusion criteria: ischaemic pain at rest (due to inability to exercise); patients with angina, arrhythmias or congestive heart failure; contraindications to the use of β‐adrenergic blockers | |

| Interventions | Treatment: propranolol (40 mg tid); metoprolol (50 mg tid) Control: placebo Duration: All participants entered a single‐blind, placebo run‐in phase period of 3 weeks followed by propranolol or metoprolol. After taking a drug for 2 weeks, participants received 2 weeks of placebo and then crossed over to the other drug | |

| Outcomes | Calf blood flow and vascular resistance | |

| Notes | Sequence 1: metoprolol before propranolol Sequence 2: propranolol before metoprolol | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Method of randomisation not stated |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not stated |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Reports 'double‐blind', no further information provided |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Analysis was intention‐to‐treat, no losses to follow‐up |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | No evidence of selective reporting |

| Other bias | Low risk | No evidence of other bias |

Lepantalo 1984a.

| Methods | Study design: randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, cross‐over trial Method of randomisation: not stated Concealment of allocation: not stated Exclusions post‐randomisation: unsure, "17 patients recruited, 14 completed study" Losses to follow‐up: unsure Intention‐to‐treat analysis: unsure | |

| Participants | Country: Finland Setting: hospital Number: 14 Age: 41 to 73 years Sex: male 9; female 5 Inclusion criteria: confirmed diagnosis of intermittent claudication (pathological ankle/arm systolic blood pressure ratio) Exclusion criteria: not stated | |

| Interventions | Treatment: metoprolol (100 to 200 mg/d); methyldopa (500 to 1000 mg/d) Control: placebo Duration: 4 × 3‐week periods (1 run‐in period with placebo and 3 treatment periods with metoprolol, methyldopa or placebo | |

| Outcomes | Vascular resistance and calf blood flow | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Method of randomisation not stated |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not stated |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Reports 'double‐blind', no further information provided |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Unclear about losses to follow‐up |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | No evidence of selective reporting |

| Other bias | Low risk | No evidence of other bias |

Lepantalo 1985.

| Methods | Study design: randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, cross‐over trial Method of randomisation: not stated Concealment of allocation: not stated Exclusions post‐randomisation: 2 excluded after run‐in period Losses to follow‐up: unsure Intention‐to‐treat analysis: unsure | |

| Participants | Country: Finland Setting: hospital Number: 7 Age: average age 60 (range 49 to 70) years Sex: male Inclusion criteria: intermittent claudication Exclusion criteria: not stated | |

| Interventions | Treatment: propranolol (80 mg bid); pindolol (5 mg bid); labetalol (200 mg bid); labetalol (400 mg bid) Control: placebo (bid) Duration: 7 × 10‐day treatment periods; a run‐in period with placebo; 5 treatment periods with propranolol (80 mg bid); pindolol (5 mg bid); labetalol (200 mg bid); labetalol (400 mg bid) and placebo (bid) | |

| Outcomes | Calf blood flow and vascular resistance | |

| Notes | "Only 7 completed the trial" | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Method of randomisation not stated |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not stated |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Reports 'double‐blind', no further information provided |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Unclear details on whether analysis was intention‐to‐treat |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | No evidence of selective reporting |

| Other bias | High risk | Exclusion criteria unclear; losses to follow‐up unclear |

Roberts 1987.

| Methods | Study design: randomised, placebo‐controlled, cross‐over trial with single‐blind and double‐blind periods Method of randomisation: randomised codes Concealment of allocation: tablets dispensed monthly by hospital pharmacy staff; independent observer aware of codes assessed participants' symptoms at each visit Exclusions post‐randomisation: 3 withdrawn because of development of other cardiovascular diseases Losses to follow‐up: 3 Intention‐to‐treat analysis: unsure | |

| Participants | Country: UK Setting: hospital Number: 23 recruited, 20 completed the study Age: mean 58 years (SEM 2) Sex: 17 male; 6 female Inclusion criteria: intermittent claudication confirmed by clinical observation and aortofemoral angiography Exclusion criteria: ischaemic pain at rest; diabetes mellitus; angina or congestive heart failure; contraindications to the use of β‐adrenergic blockers or ACE inhibitors (e.g. renal failure) | |

| Interventions | Treatment: captopril (25 mg bid); labetalol (200 mg bid); pindolol (10 mg bid); atenolol (100 mg od) Control: placebo Duration: 6 months | |

| Outcomes | Calf blood flow, claudication distance and maximum walking distance | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Randomisation codes used but method not described |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Tablets dispensed monthly by hospital pharmacy staff, no further details available |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | High risk | Independent observer aware of codes assessed participants' symptoms at each visit |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | High risk | Independent observer aware of codes assessed participants' symptoms at each visit |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Unclear whether analysis was intention‐to‐treat. 3 participants were withdrawn because of development of other cardiovascular diseases. 3 participants were lost to follow‐up |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | No evidence of selective reporting |

| Other bias | Low risk | No evidence of other bias |

Solomon 1991.

| Methods | Study design: randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, cross‐over trial Method of randomisation: computer Concealment of allocation: not stated Exclusions post‐randomisation: none Losses to follow‐up: none Intention‐to‐treat analysis: yes | |

| Participants | Country: UK Setting: hospital Number: 49 Age: 39 to 70 years Sex: 40 male; 9 female Inclusion criteria: stable intermittent claudication of at least 6 months' duration Exclusion criteria: rest pain; angina, which limited exercise before claudication; recent myocardial infarction; insulin‐dependent diabetes; serum creatinine concentrations > 200 µmol/L; contraindications to the use of β‐adrenergic blockers; co‐prescription of peripheral vasodilators, ACE inhibitors or calcium antagonists | |

| Interventions | Treatment: atenolol (50 mg bid); slow‐release nifedipine (20 mg bid); atenolol (50 mg) + slow‐release nifedipine (20 mg) bid Control: placebo Duration: each treatment given for 4 weeks with no wash‐out interval between treatments | |

| Outcomes | Claudication and walking distances, skin temperature | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Computerised randomisation |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not stated |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Reports 'double‐blind', no further information provided |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Analysis was intention‐to‐treat, no losses to follow‐up |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | No evidence of selective reporting |

| Other bias | Low risk | No evidence of other bias |

ACE: angiotensin‐converting enzyme. bid: twice daily. od: once daily. SEM: standard error of the mean. tid: three times daily.

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Aarts 1986 | In this randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial, the in vivo effect of isoxsuprine on deformability of red blood cells was studied. The study was excluded, as no data were available regarding the primary or secondary outcomes considered for this review |

| Bostrom 1986 | The short‐term effects of beta blockers with and without intrinsic sympathomimetic effects on leg blood flow and walking distance were compared in participants with intermittent claudication and hypertension. The study was excluded as it was a comparative study between atenolol (100 mg od) and pindolol (10 mg od). Placebo was not used |

| Brown 1998 | This randomised, double‐blind trial assessed single and combination therapy anti‐hypertensives in achieving target blood pressure. This study was excluded, as the drug used in the study (nifedipine) is a calcium channel blocker |

| Diehm 1993 | In this randomised, double‐blind, parallel‐group study, the effects of tertatolol (5 mg od) on lipid profile, walking tolerance and blood pressure control in participants with peripheral arterial disease were compared with those of metoprolol (200 mg od). This study was excluded, as it was a comparative study and placebo was not used |

| Diehm 2011 | Compared beta blocker with a diuretic |

| Ehrly 1987 | Compared beta blocker with another beta blocker but not with placebo |

| Espinola‐Klein 2011 | This RCT compared nebivolol with metoprolol in participants with arterial occlusive disease; however, placebo was not used, hence excluded |

| Forbes 1999 | In this randomised, double‐blind, cross‐over trial, the safety and pharmacodynamic compatibility of clopidogrel were assessed in participants taking beta blockers and calcium channel blockers. The study was excluded, as no data regarding the primary or secondary outcomes considered for this review were provided |

| Iarussi 1977 | The effects of delayed action isoxsuprine on peripheral circulation were evaluated in this trial. It was excluded, as no reference was made to participants with peripheral vascular disease |

| Karnik 1987 | The effects on peripheral blood flow of beta blockers with and without intrinsic sympathomimetic activities were assessed. The study was excluded as it was a comparator study between celiprolol (200 mg od) and metoprolol (200 mg od). Placebo was not used |

| Klieber 1986 | The effects of celiprolol (300 mg/d) and propranolol (120 mg/d) on peripheral blood flow in participants with PAD were studied in this randomised, double‐blind trial. This study was excluded as it was a comparative study, and placebo was not used |

| Konecny 1986 | In this trial, the acute effect of IV celiprolol on resting calf blood flow in healthy participants and participants with peripheral arterial disease was evaluated. The trial was excluded, as data were insufficient. |

| Lepantalo 1984b | This randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial considered the effects of a 3‐week course of metoprolol (100 to 200 mg/d) and methyldopa (500 to 1000 mg/d) on walking capacity in participants with intermittent claudication. The trial was excluded, as insufficient data were available. The values were given as multiples of baseline. However, the baseline values were not provided. |

| Novo 1985 | This study looked at chronic effects of beta blockers in lower limbs in participants with hypertension. Some of the participants for whom results were collated had peripheral vascular disease. However, this was not a randomised study of participants with peripheral vascular disease, hence it was excluded. |

| Novo 1986 | This study evaluated the effects of ketanserin on blood pressure, peripheral circulation, and haemocoagulative parameters in participants with or without arteriosclerosis obliterans. The study was excluded as ketanserin is an anti‐serotoninergic drug and is not a beta blocker. |

| Reichert 1975 | In this randomised, double‐blind trial, the effects of propranolol compared with placebo on claudication pain were tested. The study was excluded, as it had a mixed cohort of participants, and the dosages administered to different participants were different. |

| Schweizer 1996 | The effects of celiprolol (200 mg od), atenolol (50 mg od) and isosorbide (40 mg bid) on peripheral blood flow in participants with PAD were evaluated in this randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial. This trial, published in German, was excluded, as the results were presented in graphs only. |

| Skotnicki 1984 | This randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial evaluated the effects of isoxsuprine on pain‐free walking distance in participants with intermittent claudication. The data were presented in graphs, hence excluded. |

| Smith 1982 | This trial evaluated the effects of beta blockers on calf blood flow in participants with peripheral vascular disease. The results were presented in graphs only and hence were excluded. |

| Strandness 1970 | In this randomised trial, the effects of isoxsuprine (200 mg tid) and placebo on post‐exercise blood pressure were assessed. The study was excluded, as not enough data were available. |

| Svendsen 1985 | In this randomised, cross‐over trial, the effects of acebutolol (400 mg od) and metoprolol (100 mg bid) on blood pressure and walking distances in participants with essential hypertension and chronic intermittent claudication were compared. The trial was excluded, as it was a comparator study (placebo was not used). |

| van de Ven 1994 | Compared beta blocker with ACE inhibitor. |

bid: two times daily IV: intravenous od: once daily PAD: peripheral arterial disease tid: three times daily

Differences between protocol and review

Risk of bias has been investigated using the 'Risk of bias' tool developed by The Cochrane Collaboration (Higgins 2011), not by methods described by Jadad 1996 and Schulz 1995, as originally planned in the protocol and in the previous review version.

Contributions of authors

All three review authors contributed to selection of trials and assessment of their quality.

All three review authors independently extracted data. Anthony Da Silva resolved disagreements.

Sources of support

Internal sources

No sources of support supplied

External sources

-

Chief Scientist Office, Scottish Government Health Directorates, The Scottish Government, UK.

The Cochrane PVD Group editorial base is supported by the Chief Scientist Office.

Declarations of interest

None known.

New search for studies and content updated (no change to conclusions)

References

References to studies included in this review

Clement 1980 {published data only}

- Bogaert MG, Clement DL. Lack of influence of propranolol and metoprolol on walking distance in patients with chronic intermittent claudication. European Heart Journal 1983;4(3):203‐4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clement DL. Studies on the effect of alpha‐ and beta‐ adrenergic blocking agents on the circulation in human limbs. Verhandelingen Van De Koninklijke Academie voor Geneeskunde van Belgie 1980;XLII(3‐4)(42):164‐214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Hiatt 1985 {published data only}

- Hiatt WR, Stoll S, Nies AS. Effect of beta‐adrenergic blockers on the peripheral circulation in patients with peripheral vascular disease. Circulation 1985;72(6):1226‐31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Lepantalo 1984a {published data only}

- Lepantalo M. Chronic effects of metoprolol and methyldopa on calf blood flow in intermittent claudication. British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology 1984;18(1):90‐3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Lepantalo 1985 {published data only}

- Lepantalo M. Chronic effects of labetalol, pindolol, and propranolol on calf blood flow in intermittent claudication. Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics 1985;37(1):7‐12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lepantalo M, Lindstorm BL, Totterman KJ. Adrenoreceptor blocking drugs and cold feet in intermittent claudication. VASA. Zeitschrift für Gefässkrankheiten 1986;15(2):135‐7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Roberts 1987 {published data only}

- Roberts DH, Tsao Y, McLoughlin GA, Breckenridge A. Placebo controlled comparison of captopril, atenolol, labetalol, and pindolol in hypertension complicated by intermittent claudication. Lancet 1987;ii:(8560):650‐3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Solomon 1991 {published data only}

- Solomon SA, Ramsay LE, Yeo WW, Parnell L, Morris‐Jones W. Beta‐blockade and intermittent claudication: placebo controlled trial of atenolol, nifedipine and their combination. BMJ 1991;303(6810):1100‐4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to studies excluded from this review

Aarts 1986 {published data only}

- Aarts PA, Banga JD, Houwelingen HC, Heethaar RM, Sixma JJ. Increased red blood cell deformability due to isoxsuprine administration decreases platelet adherence in a perfusion chamber: a double‐blind cross‐over study in patients with intermittent claudication. Blood 1986;67(5):1474‐81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Bostrom 1986 {published data only}

- Bostrom PA, Janzon L, Ohlsson O, Westergren A. The effect of beta‐blockade on leg blood flow in hypertensive patients with intermittent claudication. Angiology 1986;37(3 pt1):149‐53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Brown 1998 {published data only}

- Brown MJ, Castaigne A, Leeuw PW, Mancia G, Rosenthal T, Ruilope LM. Study population and treatment titration in the International Nifedipine GITS Study: Intervention as a Goal in Hypertension Treatment (INSIGHT). Journal of Hypertension 1998;16(12):2113‐6. [MEDLINE: ] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Diehm 1993 {published data only}

- Diehm C, Jacobsen O, Amendt K. The effects of tertalolol on lipid profile. Cardiology 1993;83 Suppl 1:32‐40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Diehm 2011 {published data only}

- Diehm C, Pittrow D, Lawall H. Effect of nebivolol vs. hydrochlorothiazide on the walking capacity in hypertensive patients with intermittent claudication. Journal of Hypertension 2011;29:1448‐56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Ehrly 1987 {published data only}

- Ehrly AM, Landgraf H, Saeger LK. Influence of propranolol and bunitrolol on muscular tissue oxygen pressure of patients with intermittent claudication and arterial hypertension. Die Medizinische Welt 1987;38:1052‐5. [Google Scholar]

Espinola‐Klein 2011 {published data only}

- Espinola‐Klein C, Weisser G, Jagodzinski A, Savvidis S, Warnholtz A, Ostad MA, et al. Beta‐blockers in patients with intermittent claudication and arterial hypertension: results from the nebivolol or metoprolol in arterial occlusive disease trial. Hypertension 2011;58(2):148‐54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Forbes 1999 {published data only}

- Forbes CD, Lowe GD, Maclaren M, Shaw BG, Dickinson JP, Keiffer G. Clopidogrel compatibility with concomitant cardiac co‐medications: a study of its interactions with a beta blocker and a calcium uptake antagonist. Seminars in Thrombosis and Hemostasis 1999;25 Suppl 2:55‐60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Iarussi 1977 {published data only}

- Iarussi D, Ferrante MR, Garofalo S, Cristofaro M. Instrumental evaluation of the effects of a delayed‐action preparation of a isoxsuprine on the peripheral circulation [Valutazione strumentale degli effetti sul circolo periferico di un preparato di isossisuprina ad azione protratta]. La Clinica Terapeutica 1977;80(4):315‐25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Karnik 1987 {published data only}

- Karnik R, Valentin A, Slany J. Different effects of beta‐1‐adrenergic blocking agents with ISA or without ISA on peripheral blood flow. Angiology 1987;38(4):296‐303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Klieber 1986 {published data only}

- Klieber M, Resch F. Comparative studies of the effect of a cardioselective and a non‐cardioselective beta blocker on peripheral circulation in patients with arterial occlusive disease. Wiener Klinische Wochenschrift 1986;98(3):70‐3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Konecny 1986 {published data only}

- Konecny U, Ehringer H, Rasser W, Koppensteiner R, Minar E, Wachter M. The acute effect of celiprolol I.V. on the resting blood flow of calf and foot in healthy subjects and patients with peripheral arterial occlusive disease (PAOD). What is new in angiology? Trends and controversies. Zuckschwerdt W, 1986:541‐2.

Lepantalo 1984b {published data only}

- Lepantalo M, Knorring J. Walking capacity of patients with intermittent claudication during chronic antihypertensive treatment with metoprolol and methyldopa. Clinical Physiology 1984;4(4):275‐82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Novo 1985 {published data only}

- Novo S, Pinto A, Galati D, Giannola A, Forte G, Strano A. Effects of chronic administration of selective beta blockers on peripheral circulation of lower limbs in patients with essential hypertension. International Angiology 1985;4(2):229‐34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Novo 1986 {published data only}

- Novo S, Alaimo G, Abrignani MG, Giordano U, Avellone G, Pinto A, et al. Effects of ketanserin on blood pressure, peripheral circulation and haemocoagulative parameters in essential hypertensives with or without arterioscleorosis obliterans of the lower limb. International Journal of Clinical and Pharmacology Research 1986;6(3):199‐211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Reichert 1975 {published data only}

- Reichert N, Shibolet S, Adar R, Gafni J. Controlled trial of propranolol in intermittent claudication. Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics 1975;17(5):612‐5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Schweizer 1996 {published data only}

- Schweizer J, Kaulen R, Altmann E, Nierade A, Nanning T. Are beta‐blockers generally contraindicated in patients with peripheral arterial occlusive disease?. Zeitschrift fur Kardiologie 1996;85(3):193‐7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schweizer J, Kaulen R, Nierade A, Altmann E. Beta‐ blockers and nitrates in patients with peripheral arterial occlusive disease: long‐term findings.. VASA. Zeitschrift für Gefässkrankheiten 1997;26(1):43‐6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Skotnicki 1984 {published data only}

- Skotnicki SH, Gaal G, Wijn PF. The effectiveness of Isoxsuprine in patients with intermittent claudication. Angiology 1984;35(11):685‐93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Smith 1982 {published data only}

- Smith RS, Warren DJ. Effect of beta‐blocking drugs on peripheral blood flow in intermittent claudication. Journal of Cardiovascular Pharmacology 1982;4(1):2‐4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Strandness 1970 {published data only}

- Strandness D Jr. Ineffectiveness of isoxsuprine on intermittent claudication. JAMA 1970;213(1):86‐8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Svendsen 1985 {published data only}

- Svendsen TL, Jelnes R, Tonnesen KH. Is adrenergic beta receptor blockade contraindicated in patients with intermittent claudication. Acta Medica Scandinavica 1985;693:129‐32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svendsen TL, Jelnes R, Tonnesen KH. The effects of acebutolol and metoprolol on walking distances and distal blood pressure in hypertensive patients with intermittent claudication. Acta Medica Scandinavica 1986;219(2):161‐5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

van de Ven 1994 {published data only}

- Ven LL, Leeuwen JT, Smit AJ. The influence of chronic treatment with beta blockade and angiotensin converting enzyme inhibition on the peripheral blood flow in hypertensive patients with and without concomitant intermittent claudication. A comparative cross‐over trial. VASA. Zeitschrift für Gefässkrankheiten 1994;23(4):357‐62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Additional references

ACCF/AHA 2012

- Anderson JL, Adams CD, Antman EM, Bridges CR, Califf RM, Casey DE Jr, et al. 2012 ACCF/AHA focused update incorporated into the ACCF/AHA 2007 guidelines for the management of patients with unstable angina/non–ST‐elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Journal of American College of Cardiology 2013; Vol. 61, issue 23:e179 –347. [DOI] [PubMed]

Bangalore 2007

- Bangalore S, Parkar S, Grossman E, Messerli FH. A meta‐analysis of 94,492 patients with hypertension treated with beta blockers to determine the risk of new‐onset diabetes mellitus. American Journal of Cardiology 2007;100(8):1254‐62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

BNF 2013

- Joint Formulary Committee. British National Formulary. Vol. 65, London: British Medical Association and Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain, 2013. [Google Scholar]

Chen 2010

- Chen JMH, Heran BS, Perez MI, Wright JM. Blood pressure lowering efficacy of beta‐blockers as second‐line therapy for primary hypertension. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2010, Issue 1. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD007185.pub2] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Criqui 1985

- Criqui MH, Fronek A, Barrett‐Connor E, Klauber MR, Gabriel S, Goodman D. The prevalence of peripheral arterial disease in a defined population. Circulation 1985;71(3):510‐5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

George 1974

- George CF. Beta‐receptor blocking agents. Prescribers Journal 1974;14:93‐8. [Google Scholar]

Hiatt 2001

- Hiatt WR. Medical treatment of peripheral arterial disease and claudication. New England Journal of Medicine 2001;344(21):1608‐21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Higgins 2011

- Higgins JPT, Green S (editors). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. www.cochrane‐handbook.org. The Cochrane Collaboration.

Hughson 1978

- Hughson WG, Mann JI, Garrod A. Intermittent claudication: prevalence and risk factors. British Medical Journal 1978;1(6124):1379‐81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Jadad 1996

- Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, Jenkinson C, Reynolds DJ, Gavaghan DJ, et al. Assessing the quality of reports of randomised clinical trials: is blinding necessary?. Controlled Clinical Trials 1996;17(1):1‐12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Javed 2009

- Javed U, Deedwania PC. Beta‐adrenergic blockers for chronic heart failure. Cardiology in Review 2009;17(6):287‐92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Kannel 1985

- Kannel WB, McGee DL. Update on some epidemiologic features of intermittent claudication: the Framingham Study. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 1985;33(1):13‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Lassila 1986

- Lassila R, Lepantalo M, Lindfors O. Peripheral arterial disease-natural outcome. Acta Medica Scandinavica 1986;220(4):295‐301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Lavie 2009

- Lavie CJ, Messerli FH, Milani RV. Beta‐blockers as first‐line antihypertensive therapy: the crumbling continues. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 2009;54(13):1162‐4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Lindholm 2005

- Lindholm LH, Carlberg B, Samuelsson O. Should beta blockers remain first choice in the treatment of primary hypertension? A meta‐analysis. Lancet 2005;366(9496):1545‐53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

MIAMI trial

- MIAMI Trial Researchers. Metoprolol in acute myocardial infarction. Other clinical findings and tolerability. The MIAMI Trial Research Group. American Journal of Cardiology 1985;56(14):G39‐G46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Miyajima 2004

- Miyajima R, Sano K, Yoshida H. Beta‐adrenergic blocking agents and intermittent claudication: systematic review. Yakugaku Zasshi 2004;124(11):825‐31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

NICE 2010

- NICE. Chronic heart failure: management of chronic heart failure in adults in primary and secondary care. Clinical guidelines CG108: August 2010 Issue. www.nice.org.uk (accessed 7 August 2013).

Schulz 1995

- Schulz KF, Chalmers I, Hayes RJ, Altman DG. Empirical evidence of bias. Dimensions of methodological quality associated with estimates of treatment effects in controlled trials. JAMA 1995;273(5):408‐12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Wiysonge 2007

- Wiysonge CS, Bradley H, Mayosi BM, Maroney R, Mbewu A, Opie LH, et al. Beta‐blockers for hypertension. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2007, Issue 1. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD002003.pub2] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Wright 2009

- Wright JM, Musini VM. First‐line drugs for hypertension. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2009, Issue 3. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD001841.pub2] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to other published versions of this review

Paravastu 2008

- Paravastu SCV, Mendonca D, Silva A. Beta blockers for peripheral arterial disease. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2008, Issue 4. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD005508.pub2] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]