Abstract

Objective:

Although use of telemental health services is growing, there is limited research on how telemental health is being deployed. This project aimed to describe how health centers are using telemental health in conjunction with in-person care.

Methods:

The 2018 SAMHSA Behavioral Health Treatment Services Locator database was used to identify community mental health centers and federally qualified health centers with telemental health. Maximum diversity sampling was applied to recruit health center leaders to participate in semi-structured interviews. Inductive and deductive approaches were used to develop site summaries, and a matrix analysis was conducted to identify and refine themes.

Results:

20 health centers from 14 different states participated. All health centers used telepsychiatry for diagnostic assessment and medication prescribing, and 10 also offered teletherapy programs. Some health centers used their own staff to provide telemental health services while others contracted with external providers such as telemedicine vendors. In most health centers, telemental health was an adjunct to in-person care. In choosing between telemental health and in-person care, health centers often considered patient preference, patient acuity, and insurance status/payer. Although most health centers planned to continue offering telemental health, participants noted drawbacks including less patient engagement, challenges sharing information within the care team, and greater inefficiency.

Conclusions:

Telemental health is generally used as an adjunct to in-person care. Our results can inform policymakers and clinicians regarding the various delivery models that incorporate telemental health.

Despite the high burden of mental illness in the U.S., many patients lack access to specialty mental health providers. In 2018, 115 million Americans live in a mental health professional shortage area.1

Telemental health, in the form of interactive videoconferencing between a patient and provider, can increase access to specialty mental health services. Research suggests that telemental health is equivalent to in-person care in terms of quality and can expand the mental health provider workforce by making it easier for retirees and part-time workers to provide care.2,3

The use of telemental health is growing rapidly.4,5 In 2016, 38% of federally qualified health centers reported offering telehealth, with telemental health as a common application.6 A 2017 survey of 329 U.S. behavioral health organizations found that 48% used telemental health for a range of services including medication management, individual and group counseling, assessment, consultations, and crisis services.7

Despite this growth, there is limited research on how telemental health is being deployed and used in conjunction with in-person care.8 Prior research has focused primarily on barriers to establishing and sustaining telemental health or provider and patient satisfaction, typically within the context of select programs.9–14 Healthcare providers lack practical examples and guidance on how and why to use telemental health vs. in-person care for certain services and patient populations. To address this gap, we interviewed representatives from community mental health centers (CMHCs) and federally qualified health centers (FQHCs) using telemental health. The goal was to understand how different telemental health services are being used in isolation and in combination, the role of telemental health vs. in-person services, and the patient factors that impact the decision on to offer telemental health services vs. in-person care. Our goal is to inform policymakers and clinicians regarding the various delivery models that incorporate telemental health.

Methods

Study Participants and Sampling Strategy

The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) tracks organizations providing behavioral health services in the U.S., including information such as location, facility type, service setting, treatment approaches, and provision of telehealth services (yes/no). To develop a sampling frame, we identified the 1,319 CMHC and FQHCs (48% of all such clinics) in the 2018 SAMHSA Behavioral Health Treatment Services Locator database (https://findtreatment.samhsa.gov/) with telehealth capabilities. We focused on CMHCs and FQHCs because of their critical role in serving vulnerable populations.

We used maximum variation sampling to represent the diversity of experiences with telemental health among participating organizations. We selected 20 states on which to focus recruitment efforts that varied with respect to U.S. region, % of rural population, and state telemental health policy.15 We then randomly selected organizations to participate until we reached thematic saturation, defined as the point at which new interviews did not uncover new themes.

Interviews

We invited health center leaders to participate in a 60-minute telephone interview. Interviewees were given a $50 gift card and provided verbal informed consent. From February-April 2019, we completed a total of 20 semi-structured interviews.

Interviews followed a semi-structured protocol informed by the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research.16,17 Topics included history of the telemental health program, current telemental health services, relationships between originating and distant sites, telemental health program goals, the role of telemental health in the context of in-person care, and how providers decide to offer telemental health to specific patients. Interviews were recorded and transcribed. Harvard University’s institutional review board approved this study.

Analysis

Interview transcripts were uploaded into Dedoose (Dedoose, 2019), a cloud-based qualitative analysis program. We employed an inductive and deductive approach (which identified codes mapped to key research questions covered within the interview protocol as well as codes that emerged) to develop a templated site summary for each health center. We then conducted a supplemental matrix analysis, listing health centers as rows and salient categories that we developed from codes included in the site summaries as columns.18 The matrix allowed us to interpret each participant’s quotes in the context of the health center’s particular telemental health services and models and facilitate cross site comparisons. Additional details on our analyses can be found in the online supplement.

Results

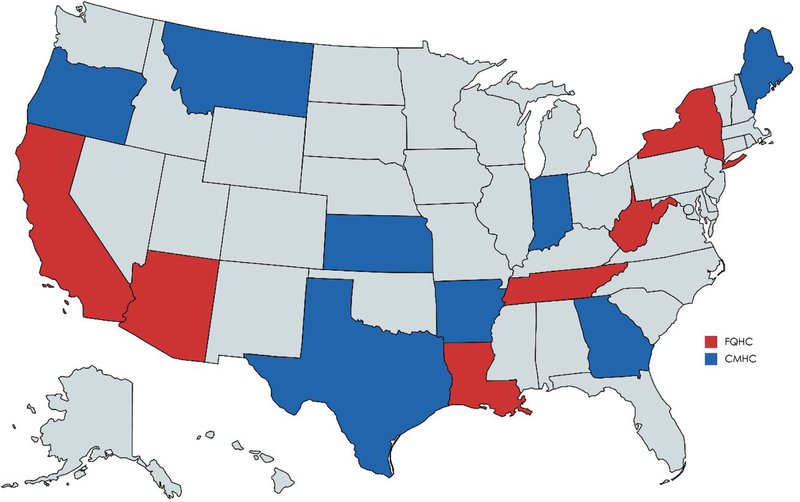

A total of 20 health centers (9 FQHCs, 11 CMHCs) from 14 different states participated (Figure 1). Thirteen health centers were in rural areas only and six had locations in both rural and urban areas (Table 1). Health center staff who participated in interviews included: chief operating officers/presidents (n=6), chief operating officers (n=3), executive directors (n=3), clinical directors (n=3), and other (n=5).

Figure 1:

States Represented Among Participating Health Centers

Table 1:

Characteristics of Participating Health Centers

| Characteristic | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| U.S. Region | ||

| Northeast | 3 | 15 |

| West | 7 | 35 |

| South | 8 | 40 |

| Midwest | 2 | 10 |

| Number of Clinic Sites | ||

| 2–5 | 7 | 35 |

| 7–10 | 10 | 50 |

| 11+ | 3 | 15 |

| Location of Clinic Sites | ||

| Rural only | 13 | 65 |

| Urban only | 1 | 5 |

| Mix of rural and urban | 6 | 30 |

| % of patients with Medicaid | ||

| <50% | 8 | 40 |

| 51–69% | 8 | 40 |

| 70+% | 4 | 20 |

How is telemental health being used

Participants distinguished between telemental health services provided to health center patients and services provided by health center staff to patients in the community who receive care at other sites. While all health centers in our sample offered telemental health services to their own patients, some had staff providing telemental health services to other organizations.

Telemental health services for health center patients.

All of the health centers offered telepsychiatry for diagnostic assessment and medication prescribing. This was the only telemental health service offered at 6 health centers (2 CMHCs and 4 FQHCs). Ten health centers (6 CMHCs and 4 FQHCs) also offered teletherapy, typically through individual therapy although group therapy via video was offered by several health centers. Six health centers provided tele-substance use disorder services including assessment, counseling, and prescribing (Table 2).

Table 2:

Telemental Health Program Services and Staffing Models

| Org Type | State | Telepsychiatry | Teletherapy | Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CMHC | Arkansas | Contracts with independent child psychiatrist for medication management, initial psychiatric evaluations, and update evaluations | None | None |

| CMHC | Georgia | Contracts with a telemedicine vendor for PNPs for medication management | None | None |

| CMHC | Kansas | Contracts with a telemedicine vendor for child psychiatrist and midlevel general provider; psychiatrist employed by health center. All provide medication management | Staff employed by health center do therapy (small program in case by case basis) | None |

| CMHC | Maine | Contracts with telemedicine vendor for psychiatrists for medication management | LCSWs employed by health center do therapy with Medicare patients; group therapy by staff employed by health center for sexual assault program | None |

| CMHC | Montana | PNPs employed by health center (who also see patients in person) provide medication management to understaffed clinic sites | LCSWs employed by health center do therapy with Medicare patients | None |

| CMHC | Oregon | Contracts with a telemedicine vendor for PNP and child psychiatrist for medication management | None | None |

| CMHC | Oregon | Contracts with telemedicine vendor and uses own (off site) staff psychiatrists and PNPs for medication management and psychiatric screening | Staff employed by health center do individual therapy, family therapy, and peer counseling | Offers tele-substance use disorder services by psychiatrists and NPs to complement in-person substance use disorder treatment Patients in school-based clinic receive counseling and prescribing services via video |

| CMHC | Texas | PNPs and psychiatrists employed by health center (who also see patients in person) provide medication management to understaffed clinic sites | Staff employed by health center do therapy (small program in case by case basis) | Intakes at all understaffed rural sites done by LPCs or LCSWs employed by health centervia video; do crisis service coverage for 48 hour extended observation |

| CMHC | Texas | Contracts with health center cooperative for psychiatrists and uses own staff for intakes and medication management | None | Psychiatrists employed by health center provide crisis assessments to crisis centers to facilities in their network |

| CMHC | Texas | Contracts with telemedicine vendor for double-boarded psychiatrists and uses own staff PNPs and psychiatrists (some who also see patients in person and others who are exclusively telehealth) | Multiple types of providers do cognitive behavioral therapy, cognitive processing therapy, rehabilitation skills training, and group therapy | None |

| CMHC | Indiana | Contracts with independent psychiatrist and PNP for medication management; PNP employed by health center (and also sees patients in-person) is available on an emergency basis for understaffed clinic sites | None | Offers tele-substance use disorder services by PNP and psychiatrist |

| FQHC | Arizona | PNP employed by health center (but located out of state) provides medication management | LCSWs employed by health center (who also see patients in-person) do therapy to understaffed clinic locations | Offers tele-substance use disorder services by PNP |

| FQHC | Arizona | Contracts with telemedicine vendor for PNP for medication management | None | None |

| FQHC | California | Contracts with telemedicine vendor for psychiatrists for medication management | LCSWs employed by health center (who also see patients in-person) do therapy to understaffed clinic locations | None |

| FQHC | California | Psychiatrists employed by health center provide medication management to understaffed clinic sites | None | None |

| FQHC | Louisiana | Contracts with academic medical center for child and adult psychiatrists for second opinion on complex cases and uses PNP employed by health center (who also sees patients in-person) for medication management | None | None |

| FQHC | New York | Contracts with independent psychiatrist for medication management | None | None |

| FQHC | New York | Contracts with adult and child psychiatrists and neurologists at academic medical center and another FQHC (all within their in-person referral networks) for medication management | Contracts with staff member at another FQHC for bilingual counseling services; LMHCs and LCSWs employed by health center do therapy | Offers tele-substance use disorder services by primary care providers and peer counselors after an initial in-person visit |

| FQHC | Tennessee | Contracts with telemedicine vendor for child psychiatrist for medication management | None | Offers tele-substance use disorder services with LCSW |

| FQHC | West Virginia | Contracts with independent psychiatrist (former employee) for medication management | Contracts with independent LCSW (former employee) for individual and group therapy | Offers tele-substance use disorder services with LCSW |

Staffing models for telepsychiatry varied across sites. Some health centers used their own on-site and off-site behavioral health staff including psychiatric nurse practitioners (PNPs) and psychiatrists to serve understaffed locations within their own network. Others contracted with telemedicine vendors or independent providers. Health centers used PNPs for medication management services as often as psychiatrists, and typically served both adults and children. In contrast, most teletherapy services were provided by health center staff rather than contracted providers.

Most health centers required patients to receive telemental health services at their physical clinic sites. Few health centers provided telemental health in patients’ homes. One Oregon CMHC described a small-scale program where patients received most mental health services from home via video after completing an initial, in-person intake.

Health center staff providing telemental health to community sites.

In addition to hosting patients receiving telemental health, at five health centers (4 CMHCs and 1 FQHC) health center staff provided telemental health services to various community organizations that hosted patients. At the FQHC, providers waivered to prescribe buprenorphine offered medications for opioid use disorder to patients at a free-standing substance abuse counseling center. The four CMHCs reported doing crisis screenings, mental health assessments, counseling, and medication management with various community organizations including detention centers, law enforcement offices, schools, hospitals, jails, and other CMHCs. Two of the CMHCs also provided crisis screenings within local hospitals so that their providers did not have to travel to the hospital.

Telemental health and in-person care.

In most health centers, patients receiving telemental health services also received in-person care. In-person services usually included psychotherapy and case management and less commonly included skills training, supported employment, supported housing, and peer support. A few health centers required all initial mental health assessments to be done in person with on-site clinicians. Patients would then be referred to telepsychiatry if the assessment suggested a need for medication initiation and management. Several interview participants believed that patient engagement is better when telemental health is combined with in-person touchpoints.

Telemental health goals and benefits

Interviewees described numerous reasons for starting and sustaining their telehealth programs. Most focused on access, including reducing wait times or bringing in specific services (e.g., medication management, child psychiatry). Often the precipitating event was the inability to recruit or maintain in-person providers and in several cases, health centers started offering telemental health services after the departure of a (in-person) provider that left a vacancy or to continue working with a provider who moved out of state.

Why health centers are not offering specific telemental health services

Several health center representatives mentioned that they did not offer teletherapy because of lower perceived need; these health centers were able to recruit and retain in-person therapists. Also, several interviewees mentioned perceptions of inferior quality. Other less common reason for not offering teletherapy included: 1) limited bandwidth (“not good to have someone come in for a therapy appointment, ready to pour out their heart or share all their struggles, and then you have a bad internet connection, or there’s glitches”); 2) concerns that no show rates would be too high; and 3) belief that therapy is a “gateway” service that should be offered in person. A handful of participants noted they did not offer telemental health in patients’ homes due to lack of reimbursement and concerns about confidentiality and safety.

Drawbacks of telemental health in implemented models

Several health center staff believed patients were less connected to telemental providers due to limitations of a video encounter. They argued that video can be “a bit of a barrier to the patient-provider relationship,” making it more challenging to establish rapport. Second, several interview participants mentioned that telemental health hampered information sharing and communication among members of the care team. Third, several health center staff believed telemental health was less efficient than in-person services given it requires extra staff and new steps in the workflow. Fourth, a couple of participants mentioned that telemental health providers cannot perform certain aspects of the mental status exam such as an assessment of patient hygiene. Finally, several FQHC representatives observed that telemental health seemed less well-suited to the same-day “warm hand-offs” between primary care and mental health providers crucial to integrated mental health services. Reasons included the preference of primary care providers to do hand-offs with in-person providers, the workflow inefficiencies of setting up telehealth equipment, and limited availability of telemental health providers.

Decision to offer telemental health vs. in-person services

At many health centers, certain services were only available via video. When services could be provided in-person or via video, a number of factors influenced the decision to offer telemental health. Leading considerations included patient preference in the context of wait times and patient acuity. Representatives of several health centers explained they offered both options to patients along with information on wait times, and to be responsive to patient’s preferences, they allowed patients to choose.

Acuity also influenced the decision to offer telemental health to individual patients. A CMHC in Montana employed PNPs who prescribed in person at the urban clinic locations as well as via video to the smaller, rural locations. Health center leaders preferred that higher acuity patients in the rural locations be seen in-person when the PNP was able to travel to those sites. At a West Virginia FQHC, teletherapy was not offered to high risk patients including those with suicidal or homicidal ideation. In contrast, in several health centers in which the in-person providers were midlevel providers and the remote providers were psychiatrists, telemental health was reserved for higher acuity and more complex patients.

A handful of interviewees mentioned the role of insurance in who is offered telemental health. Two health centers excluded Medicare patients from telemental health services because they could not be reimbursed given the particular delivery model. Medicare requires that therapy services (both in-person or via video) be delivered by certain types of healthcare providers including LCSWs, so if a health center has a teletherapy model that uses other types of staff, it cannot be reimbursed for the video visit. Furthermore, when Medicare patients needed therapy services, a few health centers offered teletherapy with LCSWs instead of in-person therapy services with other types of providers because it was eligible for reimbursement.

Future plans for telemental health

Nearly all interview participants felt that telemental health services were a permanent solution to workforce shortages. It was a “necessary evil” or required “Plan B” because of difficulty recruiting or retaining in-person providers. Many health centers described future plans to actively expand telemental health services and offer new service lines such as teletherapy and telemental health into patient homes. Participants also discussed becoming distant site providers and serving schools, jails, and emergency rooms.

Discussion

Health centers are offering a range of telemental health services. Diagnostic assessment and medication prescribing were the most common. Consistent with our prior quantitative work, at most health centers patients also received some in-person care.4

Although a handful of studies have described the telemental health services offered, 7,19,20 ours is the first to describe how the various delivery models integrate with in-person care. We hope these results, in combination with related quantitative analyses,4,5,21 can inform other health centers on the various options for structuring telemental health programs and how to decide when to offer telemental health vs. in-person care. Future research should continue to characterize the different models that are emerging and explore the impact of different delivery models on patient experience and outcomes.

Although many health centers employ behavioral health staff, only a subset of health centers in our study used their staff to provide telemental health to community organizations that host patients. This is rational when all existing staff are at capacity, but when there is some excess capacity, health centers that deploy their salaried staff to serve community partners can help patients in need and benefit financially.

The drawbacks to telemental health identified here may be partially mitigated when telemental health services co-exist alongside in-person services and when health center providers provide a mix of telehealth and in-person services to the same patient. For example, perhaps the therapeutic alliance would be strengthened if health center therapists required occasional in-person visits. Also, no show rates may be improved if telemental health visits incorporate some in-person time with other health center staff. Health centers have employed a number of these types of strategies to increase patient engagement with telemental health (e.g., require all intakes be conducted in-person prior to referral to telehealth) but few have been formally tested.

A key limitation of this research is that we only sampled CMHCs and FQHCs. As such, the themes we identified may not apply to other behavioral health organizations. Also, we interviewed different types of health centers leaders, including clinicians and non-clinicians who may have different perspectives, and could not compare urban vs. rural telehealth programs due to sample size.

Conclusions

CMHCs and FQHCs are deploying telemental health to complement in-person care. Although most health center representatives consider telemental health to have drawbacks as compared to in-person care, most consider these services to be a permanent feature in the delivery of mental health services to underserved populations that can help make care more integrated, patient-centered, and accessible.

Supplementary Material

Table 3:

Select Themes and Illustrative Quotes

| Theme | Illustrative Quote |

|---|---|

| By offering telemental health, health centers can introduce a care model that can be reimbursed | “We [CMHC in Maine] added teletherapy with LCSWs to our existing telemental health services because although several types of licensed providers were providing in-person therapy here, psychotherapy services by providers other than LCSWs and psychologists were not reimbursed by Medicare. Teletherapy allowed Medicare patients at any location in our network to receive billable services even if their specific clinic location did not have inperson LCSWs.” |

| Patient engagement is better when telemental health is combined with in-person touchpoints. | “It’s a mix. Yeah. Nobody’s receiving everything [via telehealth]…. I don’t know that this is valid, statistically, or any kind of data, I haven't seen anything, but it's engagement. I mean, you need to look the guy in the eyes and have a conversation with him. It's not the same via video.” |

| Teletherapy is not equivalent to in-person therapy with respect to quality. | “But, I think it’s [teletherapy] different than tele-psychiatry, and that I think you would lose more, because therapy is relationship-based, and that making that connection, I think that's harder to do over a screen versus, ‘how are your medications working… how is your sleep.” |

| Confidentiality and safety concerns prevent some health centers from offering telemental health into patients’ homes. | “[Telemental health in home] was something that we discussed and that decision was based on the lack of confidentiality at the patient's home. For instance, we have problems with domestic violence. We didn't feel like it was a good idea to encourage a patient to have a conversation with a therapist where they open up about everything, including the people in their lives, and leave their confidentiality up to them, when they might not even understand the risk.” |

| Patients are less connected to telemental providers due to limitations of a video encounter. | “It seems to be very difficult for the prescriber to pick up on humor when somebody is trying to be funny about something, so there tends to be miscommunication.” “When we move telepsychiatry into a clinic, we see our no show rates increasing. So the people who vote by filling out the [patient satisfaction] survey are fine with it, but the people who vote with their feet are not coming in for visits.” |

| Telemental health hampers informationsharing among members of the care team. | “Building a team around services when one of the key providers is not co-located is a challenge… Just in terms of sharing information… like in one site we have somebody go to the state hospital and then later get discharged and reentered services, and nobody had told the nurse practitioner [who provides medication management via telehealth].” |

| Patients are given the option to see a provider in-person or via telemedicine. | “Whatever the patient wants. We always offer it, so if a patient looks at us like we're nuts when we say, ‘Hey do you want to see your counselor by video?’ And if they say, ‘No, I’m not interested,’ well then that ends that discussion. We‘re very up front with patients and say, ‘We use telehealth to provide you more access. You have more options if you’re willing to use the program with telehealth.” |

Highlights:

Health centers offered a range of telemental health services; however, diagnostic assessment and medication prescribing were the most common.

Telemental health was an adjunct to in-person care.

In choosing between telemental health and in-person care, health centers often considered patient acuity.

Although most health centers planned to continue offering telemental health, participants noted drawbacks including less patient engagement, challenges sharing information within the care team, and greater inefficiency.

Drawbacks to telemental health may be partially mitigated when telemental health services co-exist alongside in-person services and when health center providers provide a mix of telehealth and in-person services to the same patient.

Acknowledgments

Funding Statement: This project was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (RO1 MH112829)

Footnotes

Disclosure: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Kaiser Family Foundation. Mental Health Care Health Professional Shortage Areas (HPSAs). 2018; https://www.kff.org/other/state-indicator/mental-health-care-health-professional-shortage-areas-hpsas/?currentTimeframe=0&sortModel=%7B%22colId%22:%22Location%22,%22sort%22:%22asc%22%7D. Accessed 5–2-19.

- 2.Bashshur RL, Shannon GW, Bashshur N, Yellowlees PM. The Empirical Evidence for Telemedicine Interventions in Mental Disorders. Telemed J E Health. 2016;22(2):87–113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Totten A Telehealth: Mapping the Evidence for Patient Outcomes From Systematic Reviews. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality;2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mehrotra A, Huskamp HA, Souza J, et al. Rapid Growth In Mental Health Telemedicine Use Among Rural Medicare Beneficiaries, Wide Variation Across States. Health affairs (Project Hope). 2017;36(5):909–917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mehrotra A, Jena AB, Busch AB, Souza J, Uscher-Pines L, Landon BE. Utilization of Telemedicine Among Rural Medicare Beneficiaries. Jama. 2016;315(18):2015–2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lin CC, Dievler A, Robbins C, Sripipatana A, Quinn M, Nair S. Telehealth In Health Centers: Key Adoption Factors, Barriers, And Opportunities. Health affairs (Project Hope). 2018;37(12):1967–1974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mace S, Boccanelli A, Dormond M. The use of telehealth witin behavioral health settings. University of Michigan;2018. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lauckner C, Whitten P. The State and Sustainability of Telepsychiatry Programs. The journal of behavioral health services & research. 2016;43(2):305–318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cunningham DL, Connors EH, Lever N, Stephan SH. Providers’ perspectives: utilizing telepsychiatry in schools. Telemed J E Health. 2013;19(10):794–799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gibson K, O’Donnell S, Coulson H, Kakepetum-Schultz T. Mental health professionals’ perspectives of telemental health with remote and rural First Nations communities. Journal of telemedicine and telecare. 2011;17(5):263–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Saurman E, Kirby SE, Lyle D. No longer ‘flying blind’: how access has changed emergency mental health care in rural and remote emergency departments, a qualitative study. BMC health services research. 2015;15:156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Malas N, Klein E, Tengelitsch E, Kramer A, Marcus S, Quigley J. Exploring the Telepsychiatry Experience: Primary Care Provider Perception of the Michigan Child Collaborative Care (MC3) Program. Psychosomatics. 2019;60(2):179–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boydell KM, Volpe T, Pignatiello A. A qualitative study of young people’s perspectives on receiving psychiatric services via televideo. Journal of the Canadian Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry = Journal de l’Academie canadienne de psychiatrie de l’enfant et de l’adolescent. 2010;19(1):5–11. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Trondsen MV, Bolle SR, Stensland GO, Tjora A. Video-confidence: a qualitative exploration of videoconferencing for psychiatric emergencies. BMC health services research. 2014;14:544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Center for Connected Health Policy. State Telehealth Laws and Reimbursement Policies. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haverhals LM, Sayre G, Helfrich CD, et al. E-consult implementation: lessons learned using consolidated framework for implementation research. Am J Manag Care. 2015;21(12):e640–647. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hadjistavropoulos HD, Nugent MM, Dirkse D, Pugh N. Implementation of internet-delivered cognitive behavior therapy within community mental health clinics: a process evaluation using the consolidated framework for implementation research. BMC psychiatry. 2017;17(1):331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Forman JH, Robinson CH, Krein SL. Striving toward team-based continuity: provision of same-day access and continuity in academic primary care clinics. BMC health services research. 2019;19(1):145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lambert D, Gale J, Hartley D, Croll Z, Hansen A. Understanding the Business Case for Telemental Health in Rural Communities. The journal of behavioral health services & research. 2016;43(3):366–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Uscher-Pines L, Bouskill K, Sousa J, Shen M, Fischer S. Experiences of Medicaid Programs and Health Centers in Implementing Telehealth. Santa Monica: RAND Corporation;2019. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Choi S, Wilcock AD, Busch AB, et al. Association of Characteristics of Psychiatrists With Use of Telemental Health Visits in the Medicare Population. JAMA psychiatry. 2019;76(6):654–657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.